Logical Fallacies Akos Gyarmathy What is an Argument

![3. Composition Example: • “[he is] being able to walk while sitting” • Words 3. Composition Example: • “[he is] being able to walk while sitting” • Words](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19a71caca4734cfb1acc970b0d7a87a9/image-16.jpg)

- Slides: 38

Logical Fallacies Akos Gyarmathy

What is an Argument? • An argument is a presentation of reasons for a particular standpoint • It is composed of premises • Premises are statements that express your reason or evidence • These premises must be arranged in an appropriate way in order to support your conclusion

What is an argument? • To craft a strong argument, one must… • Possess a certain degree of familiarity with the subject • Use good premises • Find good support for one’s conclusion • Focus only on the most relevant part of the issue • Don’t get sidetracked by rabbit trails! • Only make claims that are capable of being supported • This means avoiding sweeping claims, as those are rarely supportable

What is a fallacy? • When an argument fails in one of the previously mentioned ways, that failing is called a fallacy • Essentially, fallacies are defects in an argument • They are very common and can be quite convincing • Most of us have likely been convinced by a fallacious argument before. In fact, we’ve likely presented one!

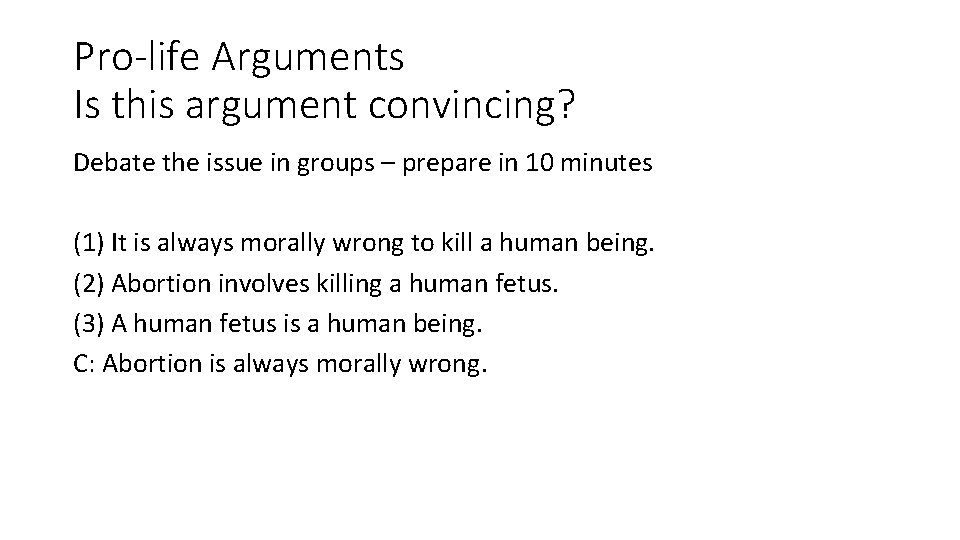

Pro-life Arguments Is this argument convincing? Debate the issue in groups – prepare in 10 minutes (1) It is always morally wrong to kill a human being. (2) Abortion involves killing a human fetus. (3) A human fetus is a human being. C: Abortion is always morally wrong.

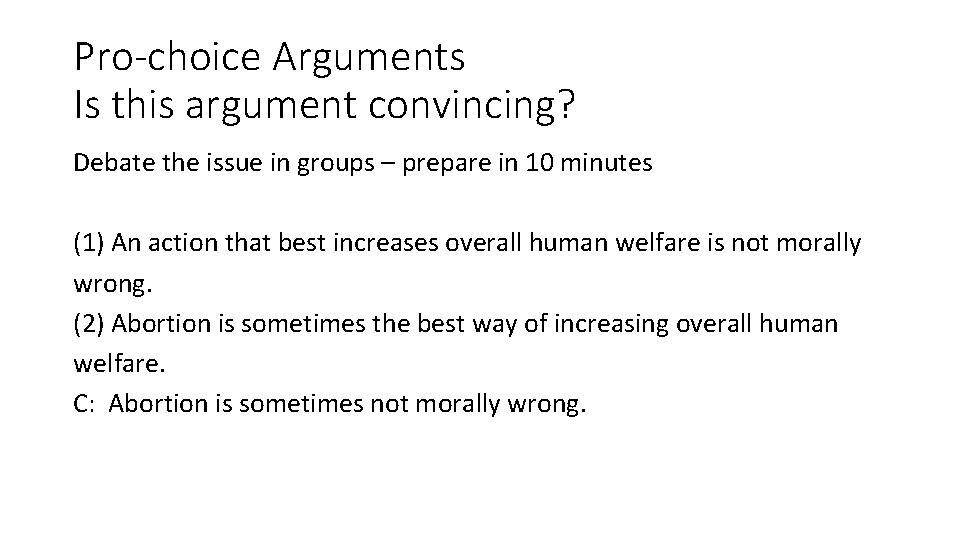

Pro-choice Arguments Is this argument convincing? Debate the issue in groups – prepare in 10 minutes (1) An action that best increases overall human welfare is not morally wrong. (2) Abortion is sometimes the best way of increasing overall human welfare. C: Abortion is sometimes not morally wrong.

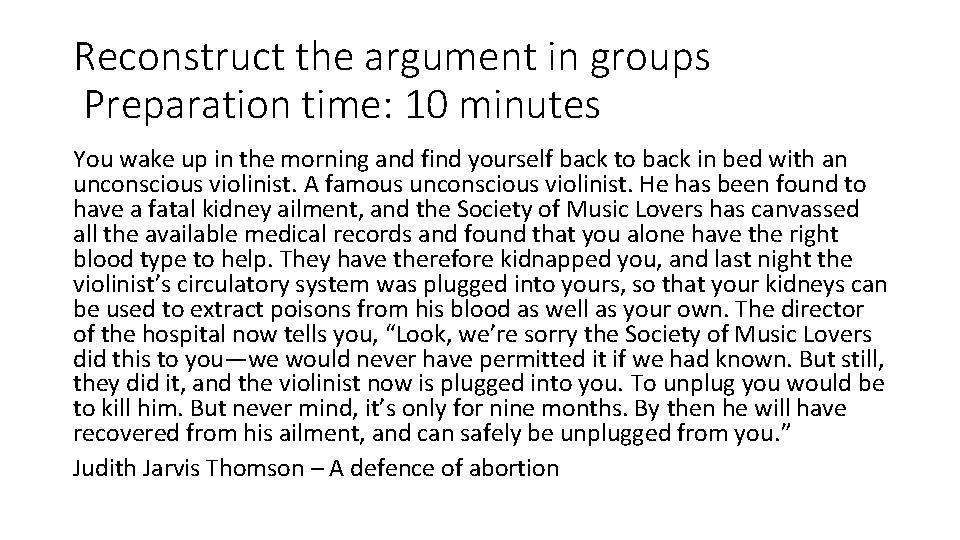

Reconstruct the argument in groups Preparation time: 10 minutes You wake up in the morning and find yourself back to back in bed with an unconscious violinist. A famous unconscious violinist. He has been found to have a fatal kidney ailment, and the Society of Music Lovers has canvassed all the available medical records and found that you alone have the right blood type to help. They have therefore kidnapped you, and last night the violinist’s circulatory system was plugged into yours, so that your kidneys can be used to extract poisons from his blood as well as your own. The director of the hospital now tells you, “Look, we’re sorry the Society of Music Lovers did this to you—we would never have permitted it if we had known. But still, they did it, and the violinist now is plugged into you. To unplug you would be to kill him. But never mind, it’s only for nine months. By then he will have recovered from his ailment, and can safely be unplugged from you. ” Judith Jarvis Thomson – A defence of abortion

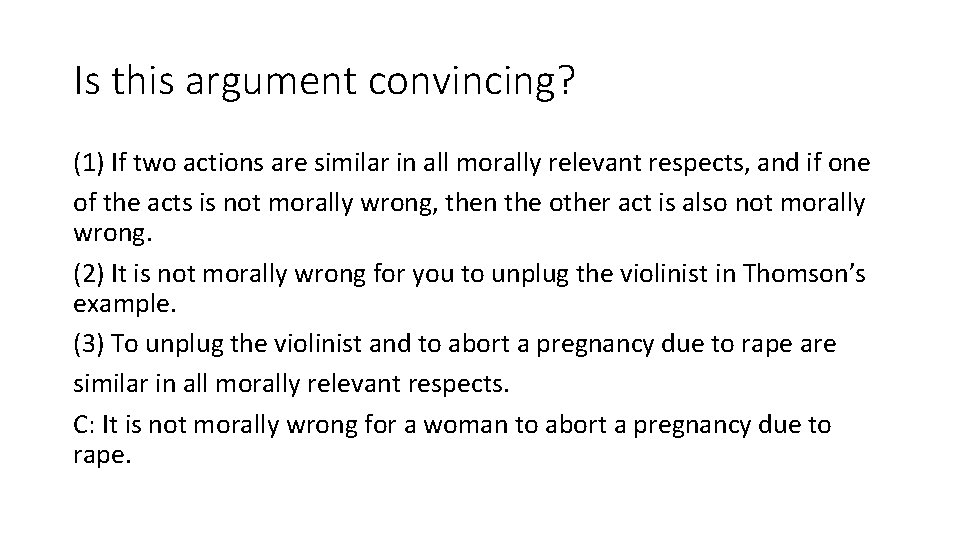

Is this argument convincing? (1) If two actions are similar in all morally relevant respects, and if one of the acts is not morally wrong, then the other act is also not morally wrong. (2) It is not morally wrong for you to unplug the violinist in Thomson’s example. (3) To unplug the violinist and to abort a pregnancy due to rape are similar in all morally relevant respects. C: It is not morally wrong for a woman to abort a pregnancy due to rape.

Slippery slope fallacy A man is clocked at fifty-six miles per hour by a radar detection unit of the highway patrol in a fifty-five mile per hour speed limit zone. He argues to the patrolman that he should not get a ticket because the difference of one mile per hour in speed is insignificant: “After all it’s really arbitrary that the agreed-upon speed limit is fifty-five rather than fifty-six isn’t it? It’s just because fifty-five is a round number that it is chosen as the limit. ”

Types of Fallacies • There are many, many fallacies – far too many for us to look at them all in this presentation • We will be examining 16 of the more common fallacies • Formal fallacy • An argument A commits a formal fallacy (in the strict sense) if and only if A has F as its logical form, F is a fallacious form, and A inherits the fallacy form F. • Informal fallacy • Formally explicable fallacy • An argument A commits a formally explicable fallacy of type T if and only if there is at least one logical form F that enters into the explanation of how A comes to commit fallacy T and yet F not itself exhibit that fallacy. • Formally inexplicable fallacy • An argument that cannot be reduced to a formally invalid argument scheme.

1. Equivocation • Using an ambiguous term in a question. • Why is it a problem? • The question itself will become ambiguous, • The Answerer may grant the premise asked for taking the question in one sense, whereas the Questioner uses it in another sense as he deduces his conclusion. • If the ambiguous term occurs in theses of the Answerer and of the Questioner, it may be that it has a different sense in each thesis, so that there is no real contradiction.

1. Equivocation Using an ambiguous term in a question Example: A feather is light. What is light cannot be dark. Therefore, a feather cannot be dark. “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country. ” JFK Margarine is better than nothing. Nothing is better than butter. Therefore, margarine is better than butter.

2. Amphiboly If a sentence contains no ambiguous words, it may still be an ambiguous sentence because it allows two ways of being parsed. Why is it a problem? • The question itself will become ambiguous, • The Answerer may grant the premise asked for taking the question in one sense, whereas the Questioner uses it in another sense as he deduces his conclusion. • If the ambiguous sentence occurs in theses of the Answerer and of the Questioner, it may be that it has a different sense in each thesis, so that there is no real contradiction.

2. Amphiboly Ambiguous sentence because it allows two ways of being parsed Example: • No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger… (Fifth amendment of US constitution)

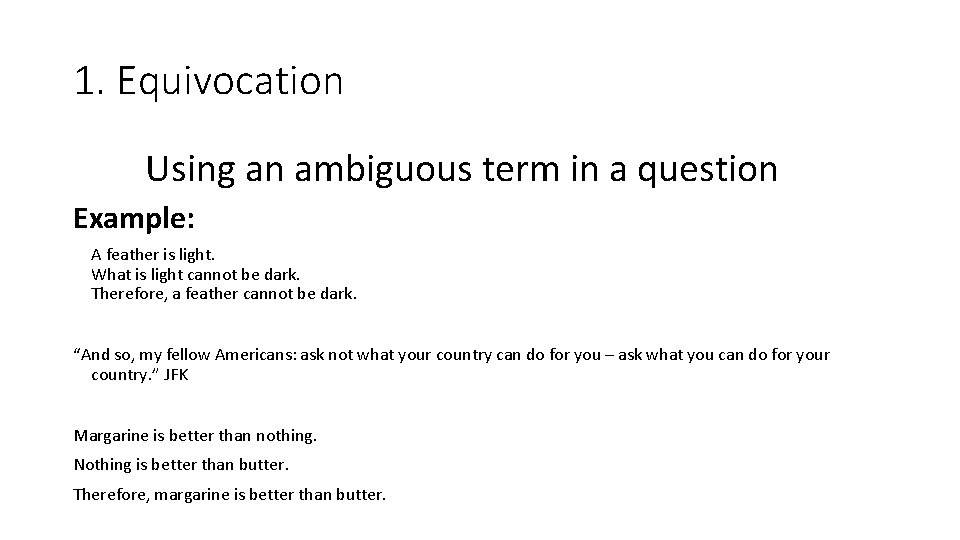

3. Composition Fallacies dependent on the use of language and concern the groupings of words. – shifting from the divided reading of a sentence to the composed reading. Why is it a problem? • May be different from amphiboly if one sentence can be read as two different sentences. • The question itself will become ambiguous, • The Answerer may grant the premise asked for taking the question in one sense, whereas the Questioner uses it in another sense as he deduces his conclusion. • If the ambiguous sentence occurs in theses of the Answerer and of the Questioner, it may be that it has a different sense in each thesis, so that there is no real contradiction.

![3 Composition Example he is being able to walk while sitting Words 3. Composition Example: • “[he is] being able to walk while sitting” • Words](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/19a71caca4734cfb1acc970b0d7a87a9/image-16.jpg)

3. Composition Example: • “[he is] being able to walk while sitting” • Words can be grouped either as • “[he is] ((being able to (walk))(while sitting))” • (divided reading: “while sitting” is placed at the same level as “being able to”) or • “[he is] (being able to ((walk) (while sitting)))” • (composed reading: “while sitting” is brought into the scope of “being able to”).

3. Composition Example: “This fragment of metal cannot be broken with a hammer, therefore the machine of which it is a part cannot be broken with a hammer. ” Human cells are invisible to the naked eye. Humans are made up of human cells. Therefore, humans are invisible to the naked eye.

4. Division Fallacies dependent on the use of language and concern the groupings of words. – shifting from the composed reading of a sentence to the divided reading. Why is it a problem? • May be different from amphiboly if one sentence can be read as two different sentences. • The question itself will become ambiguous, • The Answerer may grant the premise asked for taking the question in one sense, whereas the Questioner uses it in another sense as he deduces his conclusion. • If the ambiguous sentence occurs in theses of the Answerer and of the Questioner, it may be that it has a different sense in each thesis, so that there is no real contradiction.

4. Division • Fallacies dependent on the use of language and concern the groupings of words. – shifting from the composed reading of a sentence to the divided reading. Examples A Boeing 747 can fly unaided across the ocean. A Boeing 747 has jet engines. Therefore, one of its jet engines can fly unaided across the ocean. Functioning brains think. Functioning brains are nothing but the cells that they are composed of. If functioning brains think, then the individual cells in them think.

5. Fallacy of accent or intonation Shifting from one interpretation of a sentence to an other by changing accent/intonation. • For ancient greek, in some cases, two words that were indistinguishable when written, or sloppily pronounced, could be distinguished by their different accents, if pronounced correctly. • If an utterance of a sentence S contains such a word, the utterance could sometimes be taken to correspond also to another sentence S’, and thus to carry two distinct messages: S and S’. • If the Questioner takes advantage of this fact by shifting from one message to the other one, he will commit the fallacy of accent.

5. Fallacy of accent or intonation • Shifting from one interpretation of a sentence to an other by changing accent/intonation. • Examples • I didn't take the test yesterday. (Somebody else did. ) • I didn't take the test yesterday. (I did not take it. ) • I didn't take the test yesterday. (I did something else with it. ) • I didn't take the test yesterday. (I took a different one. ) • I didn't take the test yesterday. (I took something else. ) • I didn't take the test yesterday. (I took it some other day. )

5. Fallacy of accent or intonation • Shifting from one interpretation of a sentence to an other by changing accent/intonation. • Examples • I love your mother’s cooking.

6. Petitio Principii - Begging the Question • The arguer asks the audience to simply accept the conclusion without providing any real evidence, either through the use of circular reasoning or by simply ignoring an important (but questionable) assumption that the argument rests on. • Circular reasoning occurs when the premise states the same thing as the conclusion. • Harder to detect than many other fallacies Example 1: Adam: God must exist. Josh: How do you know? Adam: Because the Bible says so. Josh: Why should I believe the Bible? Adam: Because the Bible was written by God. Example 2: “If such actions were not illegal, then they would not be prohibited by the law. ”

7. Post hoc (False Cause) • Post hoc comes from the Latin phrase, post hoc, ergo propter hoc which, when translated, is “after this, because of this. ” • This fallacy assumes that because X precedes Y, therefore X caused Y. • Superstitious beliefs are often due to the Post Hoc Fallacy: an athlete wears their “lucky socks” and wins the game, etc. Example: (1) Cell phone usage has increased exponentially in the last 20 years. (2) Researchers discovered that the incidences of brain cancer have also increased in that time. (3) Therefore, cell phone usage must cause brain cancer.

8. Hasty Generalization • Making assumptions about an entire group of people, or a range of cases based on an inadequately small sample • Creates a general rule based on a single case • Stereotypes are a common example Example: (1) My roommate from Maine loves lobster ravioli. (2) Therefore, all people from Maine must love lobster ravioli.

9. Missing the Point • The premise supports a conclusion other than the one it is meant to support Example: (1) There has been an increase in burglary in the area. (2) More people are moving into the area. (3) Therefore, the burglary is directly caused by the increased number of people moving into the area.

10. Slippery Slope • Falsely assuming that one thing will inevitably lead to another, and another, until we have reached some unavoidable dire consequence! • It does not allow for the idea that one can stop at any point on the slope – it does not necessarily have to lead to the inevitable dire consequence. • Restraint is possible! Example: (1) If you buy a Green Day album, then you will buy The Avengers. (2) Before you know it, you’ll be a punk with green hair and tats. (3) If you don’t want to have green hair, then you can’t buy a Green Day album.

11. Weak Analogy • Many arguments rely on an analogy between two or more objects, ideas, or situations • However, drawing an analogy alone is not enough to prove anything • It is crucial to make sure that the two things being compared are truly alike in the relevant areas Example: -“Life is like a box of chocolates – you never know what you’re going to get. ” -How similar are life and a box of chocolates?

12. Appeal to Authority • This does not refer to appropriately citing an expert, but rather when an arguer tries to get people to agree with him/her by appealing to a supposed authority who isn’t much of an expert. Example: “Gun laws should be extremely strict and it should be incredibly difficult to acquire a gun. Many respected people, such as actor Brad Pitt, have expressed their support of this movement. ”

13. Appeal to Pity • Attempting to convince an individual to accept a conclusion by making them feel sorry for someone Example: “I know the paper was due today, but my computer died last week, and then the computer lab was too noisy, so while I was on my way to the library, a cop pulled me over and wrote me a ticket, and I was so upset by the ticket that I sat by the side of the road crying for 3 hours! You should give me an A for all the trouble I’ve been through!” ((These fallacies are quite common around the due date of the final paper!))

14. Appeal to Ignorance • Essentially, this fallacy states that because there is no conclusive evidence, we should therefore accept the arguer’s conclusions on the subject. • The arguer attempts to use the lack of evidence as support for a positive claim about the truth of a conclusion. • The exception to this fallacy is in the case of qualified scientific research Example: (1) Not a single report of a flying saucer has ever been authenticated. (2) Therefore, flying saucers don’t exist.

15. Ad populum (Bandwagon) • Also referred to as the bandwagon fallacy, the arguer tries to convince the audience to do or believe something because everyone else (supposedly) does Example: (1) An increasing number of people are turning to yoga as a way to get in touch with their inner-being (2) Therefore, yoga helps one get in touch with their inner-being

16. Ad hominem • Attacking the opponent instead of the opponent’s argument Example: “Allison Smith is a bad mother, whose idea of parenting is leaving her children with the nanny. Therefore, we shouldn’t listen to her ideas on improvements in the college classroom. ”

17. Tu quoque - appeal to hypocrisy • In this fallacy, the arguer points out that the opponent has actually done thing he or she is arguing against, and concluding that we do not have to listen to the argument. Example: Mother: Smoking is bad for your health and expensive! I hope to never see you do it. Daughter: But you did it when you were my age! Therefore, I can do it too!

18. Straw Man • The arguer sets up a weaker version of the opponent’s position and seeks to prove the watered-down version rather than the position the opponent actually holds. • Through this misrepresentation, the arguer concludes that the real position has been refuted. Example: “Those who seek to abolish the death penalty are seeking to allow murderers and others who commit heinous crimes to simply get off scot-free with no consequence for their actions!”

19. Red Herring • The arguer goes off on a tangent midway through the argument, raising a side issue that distracts the audience from the actual argument. Example: “We admit that this measure is unpopular. But we also urge you to note that there are so many issues on this ballot that the whole thing is getting ridiculous. ”

20. False Dichotomy • In this fallacy, the arguer sets up the situation so that it looks as though there are only two choices. When the arguer then eliminates one of the choices, it appears that there is only one option left – the arguer’s assertion! • There is rarely only 2 choices – if we were to think about them all, it may not appear to be as clear a choice. Example: (1) I can’t find my book! It was either stolen, or I never had it. (2) I know I had it; (3) Therefore, it must have been stolen!

How To Prevent Fallacies 1. 2. 3. 4. Pretend to argue against yourself List the evidence for each of your main points Investigate your own personal fallacies Give the appropriate amount of proofs for your claims • Remember, broad claims need more proof than narrow claims! 5. Fairly characterize the arguments of others