Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation May Lee MD Overview

Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation May Lee, MD

Overview Assessment of readiness for liberation � Signs of poor clinical tolerance � Complicating factors to extubation � When to consider tracheostomy �

While still intubated… � Goal is to identify the least necessary support for the patient on the ventilator ● � “Least PEEP” � Least PEEP necessary to keep O 2 sats > 8890% on a non-toxic Fi. O 2 (< 0. 60) Once critical illness stabilized, want the patient to have some spontaneous respiratory efforts � Completely passive MV may lead to diaphragm dysfunction and persistent respiratory failure

While still intubated… � “Readiness” trials can occur even without intent for extubation ● ● ● Better sense of lung mechanics May surprise the care providers No Harm if done correctly

Liberation from Mechanical Ventilation � How do you know when a patient is ready for liberation?

Minimal Necessities: Grade A Evidence � � � Evidence for some reversal of the underlying cause for respiratory failure Adequate oxygenation Hemodynamic stability ● ● � Absence of active myocardial ischemia Absence of clinically significant hypotension Ability to initiate an inspiratory effort

Minimal Necessities: The Usual Approach � � � Absence of agitation (NOT dangerous to self or others) Oxygen saturation > 88% Fi. O 2 < 0. 5 PEEP < 7. 5 cm H 20 No evidence of active myocardial ischemia No significant use of vasopressors or inotropes ( da Silva Crit Care. 2006) ● ● � Patient exhibiting inspiratory efforts Ventilator rate decreased up to 50% of baseline level for up to 5 min to detect inspiratory efforts No evidence of increased intracranial pressure

The Test for Readiness � � Goal: Assess whether the patient will still be able to breathe comfortably (slow and deep) without the assistance of the ventilator. SBT: a time-limited test of patient breathing performance while the tube is still in position ● � Most common methods used ● ● ● � Patient is in control of respiratory rate and tidal volume Pressure Support Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) T piece trial SIMV weaning

T-Piece � Inspiration and Expiration ● � Expiratory Pause ● � Fresh gas washes the expired gas out of the reservoir tube, filling it with fresh gas for the next inspiration Advantage: Clearly best approximates stress of breathing without support ● � Occur through the reservoir tube Measure RR and oxygenation (with pulse oximeter) Disadvantage: Is it too hard? ● Need tachometer to measure tidal volumes

CPAP � CPAP – Continuous Positive Airway Pressure ● ● ● Equivalent of PEEP only Patient breathes tidal volumes without any assistance above the continuous column of air (CPAP) at their own choice of respiratory rate Practitioner supplies CPAP level (PEEP) and Fi. O 2

Pressure Support � Pressure Support ● ● ● The same as the above PLUS… The ventilator senses the inspiratory effort of a patient and delivers an assistance of pressure generating (usually a larger than CPAP) tidal volume Practitioner supplies PS level, PEEP level, and Fi. O 2

Weaning on Pressure Support � Excellent mode of MV, but less commonly used ● ● � Usually implemented when… ● ● � Team sets PS/PEEP/Fi. O 2 Patient controls RR and TV Patient fights/dislikes AC or SIMV mode of ventilation � Desire to awaken patient outweighs goals of low tidal volumes Patient acclimating to newly-acquired stiff lungs Gradual reductions in pressure support until SBT equivalent is achieved

SIMV Weaning � Recall how SIMV works ● ● � Usual weaning ● ● � Minimum # of volume-assisted, synchronized breaths Breaths above set RR are either unassisted or given supplementary pressure support Gradual reductions in support of non-volume controlled breaths Decreased #’s of mandated breaths SLOWEST METHOD for liberating – AVOID! Esteban A et al. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 345 -50

Comparison of the different methods of weaning � � Prospective randomized multicenter trial of 546 pts randomly assigned to undergo one of four weaning techniques: intermittent mandatory ventilation, pressure-support ventilation, intermittent trials of spontaneous breathing (t-piece or CPAP 5) at least twice a day, and once-daily trial of spontaneous breathing Found that once-daily trial of spontaneous breathing led to extubation three time more quickly than IMV, and twice as quickly as PS. Multiple trials equal to once daily trials Esteban A et al. N Engl J Med 1995; 332: 345 -50

Preparing for an SBT � Patient positioning ● ● � Airway Suctioning ● � Perform fully prior to initiation Hold Tube Feeds ● � VAP prevention mandates at least 30° elevation More upright positioning may improve the outcome further � Obese and Ascites � Weak Want empty stomach if extubation planned Sedative Management ● Controversial

Sedation Management � At the very least, the patient must have: ● ● � Intact respiratory drive to begin Able to manage secretions to extubate Sedation management in between is uncertain ● ● Avoid sedative-induced hypoventilation Avoid anxiety and/or hyperactive delirium

Beginning the SBT � THE FIRST 5 MINUTES ARE CRUCIAL ● Apnea is not uncommon for the first 30 seconds to several minutes � � � Usually either sedative/narcotic induced (already screened for) OR iatrogenic hyperventilation p. CO 2 is the most potent stimulus to breathe Patients who have been ventilated to a low PCO 2 (esp. patients with COPD and baseline retention) must allow the CO 2 to climb to a threshold If it continues, reassess sedative and especially narcotic dosing and hold/down-titrate At 5 minutes, the practitioner should have a good sense of the patient’s anticipated performance

Evaluating for Success � Look at the Patient! ● � Look at the Vital Signs! ● � Diaphoresis, Nasal Flaring, Accessory muscle use, abdominal paradox, agitation Tachycardia, HTN, Pulse Oximetry Look at the Ventilator! ● Note the RR and Tidal Volume

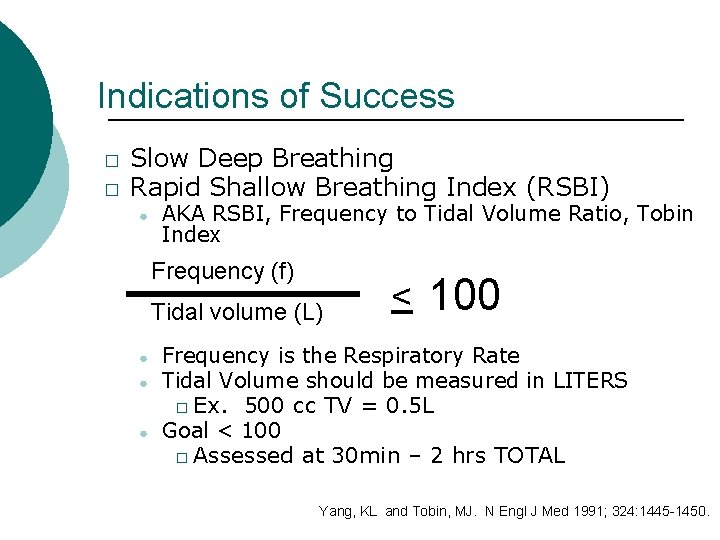

Indications of Success � � Slow Deep Breathing Rapid Shallow Breathing Index (RSBI) ● AKA RSBI, Frequency to Tidal Volume Ratio, Tobin Index Frequency (f) Tidal volume (L) ● ● ● < 100 Frequency is the Respiratory Rate Tidal Volume should be measured in LITERS � Ex. 500 cc TV = 0. 5 L Goal < 100 � Assessed at 30 min – 2 hrs TOTAL Yang, KL and Tobin, MJ. N Engl J Med 1991; 324: 1445 -1450.

Signs of poor clinical tolerance � Rapid-shallow breathing ● ● � Ineffective respiratory efforts ● � Total respiratory rate > 35 RSBI – Rapid-shallow breathing index > 100 Total respiratory rate < 8 Hypoxia ● Sp. O 2 < 88%

Signs of poor clinical tolerance � Respiratory Distress ● ● ● � Any abrupt changes in mental status ● � � HR > 120% of the 0600 rate AND either < 60 BPM or > 130 BPM Marked use of accessory muscles Abdominal paradox Diaphoresis Marked subjective dyspnea Sustained anxiety, agitation, somnolence, coma New arrythmia Signs of myocardial ischemia

Key Rules � SBT’s should last a minimum of 30 minutes and a maximum of 2 hours ● ● RSBI at 30 min generally no different than 2 hrs Uncertainties at 30 minutes may benefit from longer testing � ● � Successful completion of 2 hr SBT indicates an 85 -90% chance of successfully staying off MV for 48 hrs Avoid exhausting the patient Is a blood gas necessary? ● Rarely � � ● Oxygenation easily described by pulse oximeter Ventilation described by RR and TV However, it may help in patients with… � � Slowly evolving mental status Advanced COPD who breathe slowly and ineffectively (can be missed by an inexperienced evaluator)

If they Fail… � Describe HOW � One SBT per day suffices ● Remedy the problem before next trial

Why did they fail? � Increased work of breathing? ● ● Check electrolytes (potassium, phosphorous) Optimize nutrition Agitation Airflow Obstruction � Tracheobronchial tree – bronchodilators/suctioning +/- steroids � Artificial airway – suctioning, tubing

Why did they fail? � Hypoxia ● Atelectasis � Old age, obesity, recumbency, narcoticinduced shallow breathing � Lung injury that eroded surfactant ● New pulmonary edema � Increased return of blood to the chest – risky with poor LV function ● Ischemia

If they Pass � Review the status of secretions ● � Copious secretions requiring suction at hourly (or less) intervals are a relative contraindication Review the strength of cough and gag ● Moderate intensity is necessary unless there are scant to no secretions

Preparing to Extubate ▪ ▪ ▪ Verify patient sitting upright Suction the airways (again) and any secretions that might pool above the cuff CUFF LEAK test as desired ▪ ▪ ▪ Controversial With cuff deflated, remove artificial airway Supplemental Oxygen

Extubation Controversy: Cuff Leak Testing � Consider when… ● ● � Compromise of the upper airway caused the respiratory failure The patient has been intubated > 48 hrs Several ways to perform ● ● Volume controlled ventilation Manual occlusion of ETT

SBT failed, but Extubation Anyway � � � Patient looks well, but numbers look bad Same ETT for > 7 days Repeated episodes of bronchospasm on awakening from sedation ● � � Reflex bronchospasm from ETT Obesity Respiratory Failure amenable to noninvasive positive pressure ventilation ● Obesity, COPD*, high pressure pulmonary edema *Nava, S et al. Ann Intern Med. 1998 May 1; 128(9): 721 -8.

After Extubation � � Assess for air movement – both neck and chest If the patient is in distress, look for a reversible problem ● ● Stridor (10 -20%) AND airflow obstruction � Bronchodilators � NIPPV +/- Heliox Pulmonary edema � Diuretic � NIPPV

NIPPV after Extubation � � Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation is commonly attempted Requires ● ● ● � Intact gag/cough for airway protection Reasonable mental status to tolerate mask Respiratory failure cause amenable to therapy AVOID when… ● ● ● Agitated, delirious OR inadequate airway protection No improvement after one hour* � Consider ABG to help guide decision Worsening shock *Esteban, A et al. N Engl J Med. 2004 Jun 10; 350(24): 2452 -60.

Tracheostomy TRADITIONAL ● ● Early tracheostomy at 7 days of MV is appropriate for patients in whom weaning and extubation are not likely before day 14 � Provided benefits are anticipated and the patient is clinically stable � Benefits: improved patient comfort and communication, enhanced nursing care, +/risk of laryngeal injury from ETT Only patients who are unstable and unlikely to benefit from tracheostomy, such as patients whose death is imminent, should be maintained with endotracheal tubes in place beyond 21 days

Tracheostomy � Not enough well-designed studies to establish clear guidelines regarding the timing of tracheostomy ● ● ● Study of patients with anticipated duration of MV 14 days Early trach at 48 hrs vs. procedure at 1416 days Reduced duration of MV and ICU LOS. Less injury. *Rumbak, MJ et al. Crit Care Med. 2004 Aug; 32(8): 1689 -94.

Summary � � � “Is the ventilator necessary” should be asked every day Avoid slow weaning approaches SBT performed once per day ● ● � Assess non-pulmonary obstacles for extubation ● � � Choose a comfortable mode (PS, CPAP, T-piece) Should last at least 30 min, maximum 2 hrs Describe how the patient performed (RSBI) Understand WHY the patient failed Cough/gag and mental status If extubation fails, consider NIPPV Early consideration for tracheostomy in patients with an anticipated prolonged need for MV

references � � � da Silva NB, Teixeira C, Tonietto TF, et al. Norepinephrine use at the time of extubation was not associated with weaning failure from mechanical ventilation in septic patients. Crit Care. 2006; 10(Suppl 1): P 46. doi: 10. 1186/cc 4393 ESTEBAN, A. , FRUTOS, F. , TOBIN, M. J. , ALÍA, I. , SOLSONA, J. F. , VALVERDU, V. , FERNÁNDEZ, R. , DE, l. C. , BENITO, S. , TOMÁS, R. , CARRIEDO, D. , MACÍAS, S. and BLANCO, J. , 1995. A Comparison of Four Methods of Weaning Patients from Mechanical Ventilation. N Engl J Med, vol. 332, no. 6, pp. 345 -350. Available from: https: //doi. org/10. 1056/NEJM 199502093320601 ISSN 0028 -4793. DOI 10. 1056/NEJM 199502093320601. YANG, K. L. and TOBIN, M. J. , 1991. A Prospective Study of Indexes Predicting the Outcome of Trials of Weaning from Mechanical Ventilation. N Engl J Med, vol. 324, no. 21, pp. 1445 -1450. Available from: https: //doi. org/10. 1056/NEJM 199105233242101 ISSN 0028 -4793. DOI 10. 1056/NEJM 199105233242101 Nava S, Ambrosino N, Clini E, Prato M, Orlando G, Vitacca M, et al. Noninvasive Mechanical Ventilation in the Weaning of Patients with Respiratory Failure Due to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 128: 721– 728. doi: 10. 7326/0003 -4819 -128 -9199805010 -00004 ESTEBAN, A. , FRUTOS-VIVAR, F. , FERGUSON, N. D. , ARABI, Y. , APEZTEGUÍA, C. , GONZÁLEZ, M. , EPSTEIN, S. K. , HILL, N. S. , NAVA, S. , SOARES, M. , D'EMPAIRE, G. , ALÍA, I. and ANZUETO, A. , 2004. Noninvasive Positive-Pressure Ventilation for Respiratory Failure after Extubation. N Engl J Med, vol. 350, no. 24, pp. 2452 -2460. Available from: https: //doi. org/10. 1056/NEJMoa 032736 ISSN 0028 -4793. DOI 10. 1056/NEJMoa 032736. Rumbak MJ, Newton M, Truncale T, et al. A prospective, randomized, study comparing early percutaneous dila- tional tracheotomy to prolonged translaryngeal intubation (delayed tracheotomy) in critically ill medical patients. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 1689 – 94.

- Slides: 35