LEVELS OF LANGUAGE AT WORK An Example from

- Slides: 30

LEVELS OF LANGUAGE AT WORK: An Example from Poetry

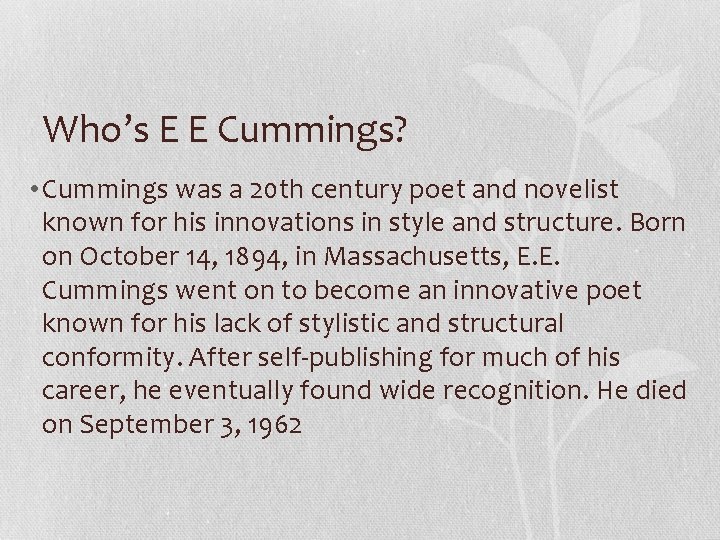

Who’s E E Cummings? • Cummings was a 20 th century poet and novelist known for his innovations in style and structure. Born on October 14, 1894, in Massachusetts, E. E. Cummings went on to become an innovative poet known for his lack of stylistic and structural conformity. After self-publishing for much of his career, he eventually found wide recognition. He died on September 3, 1962

The following is the untitled poem that was published in 1939 by the American poet E. E. Cummings love is more thicker than forget more thinner than recall more seldom than a wave is wet more frequent than to fail love is less always than to win less never than alive less bigger than the least begin less littler than forgive it is most mad and moonly and less it shall unbe than all the sea which only is deeper than the sea It is most sane and sunly and more it cannot die than all the sky which only is higher than the sky

• Such as the adjectives “Sunly” and “Moonly” • As well as the verb “Unbe” which suggests a kind of reversal in sense from “being” to “not being”

There is a high degree of regularity in the way other aspects of the poem are crafted. Observe, for example the almost mathematical symmetry of the stanzaic organization, where key words and phrasal patterns are repeated across the four verses. Indeed, all of the poem’s constituent clauses are connected grammatically to the very first word of the poem, ‘love’.

Choosing models for analysis For a start, have already been highlighted as one of the main sites for stylistic experimentation in the poem. Constituting a major word class in the vocabulary of English, adjectives ascribe qualities to entities, objects and concepts, familiar examples of which are words like large, bright, good, bad, difficult and regular. A notable grammatical feature of adjectives, and one which Cummings exploits with particular stylistic force, is their potential for gradability.

A useful test for checking whether or not an adjective is gradable is to see if the intensifying word ‘very’ can go in front of it. Indeed, all of the adjectives cited thus far satisfy this test: ‘a very bright light’, ‘the very good decision’, ‘this very regular routine’ and so on. The test does not work for another group of adjectives, known as classifying adjectives, which specify more fixed qualities relative to the noun they describe. In the following examples, insertion of ‘very’ in front of the classifying adjectives ‘former’ and ‘strategic’ feels odd: ‘the very former manager’, ‘those very strategic weapons’.

Another notable feature of adjectives, again pertinent in the present context, is the way the Grammar of English allows for material to be placed after the adjective in order to determine more narrowly its scope of reference. • The pilot was conscious of his responsibilities.

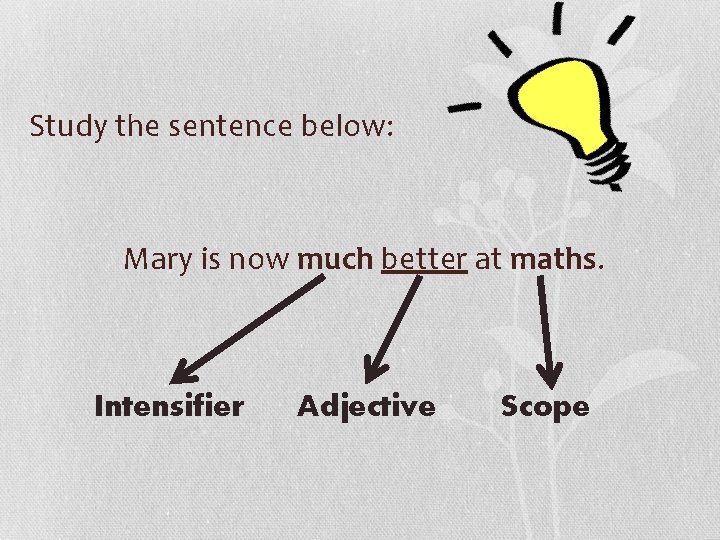

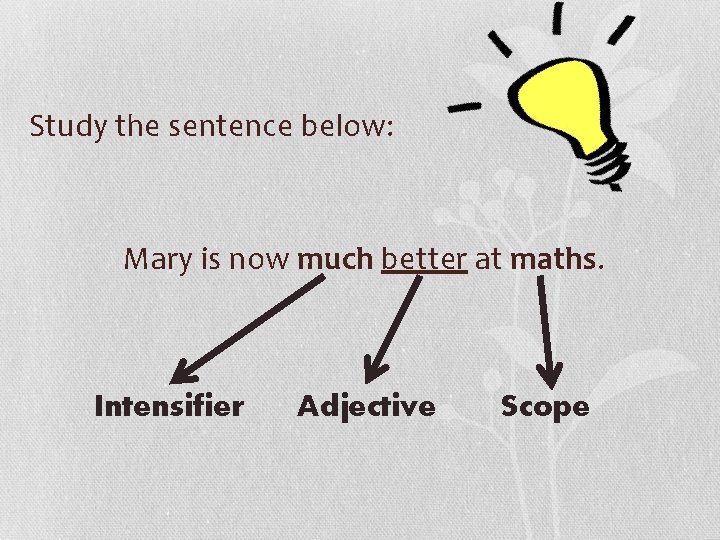

Study the sentence below: Mary is now much better at maths. Intensifier Adjective Scope

Exploring levels of language in ‘love is more thicker’ 1. Cummings constantly ‘reduplicates’ the grammatical rules for comparative and superlative gradation. 1. 1 In spite of their one-syllable status, adjectives like ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ receive both the inflectional morpheme and the separate intensifier (‘more thicker’)

Exploring levels of language in ‘love is more thicker’ 1. 2 Superlative forms of other one-syllable adjectives like ‘mad’ and ‘sane’ do not receive the inflectional morpheme (as in ‘maddest’ or ‘sanest’) buts are instead fronted, more unusually, by separate words: ‘most mad’ and ‘most sane’. 1. 3 Further variation on the pattern emerges where markers of both positive and inferior relations are mixed together in the same adjective phrase. ‘big’ to ‘less bigger’ and ‘little’ to ‘less littler’

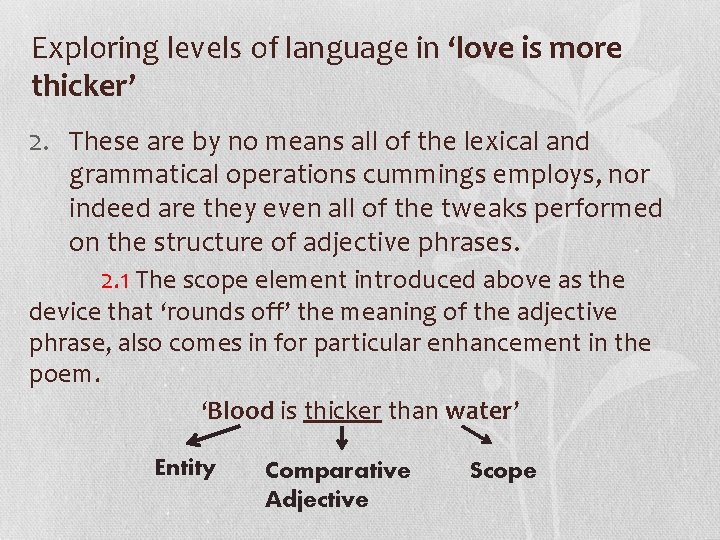

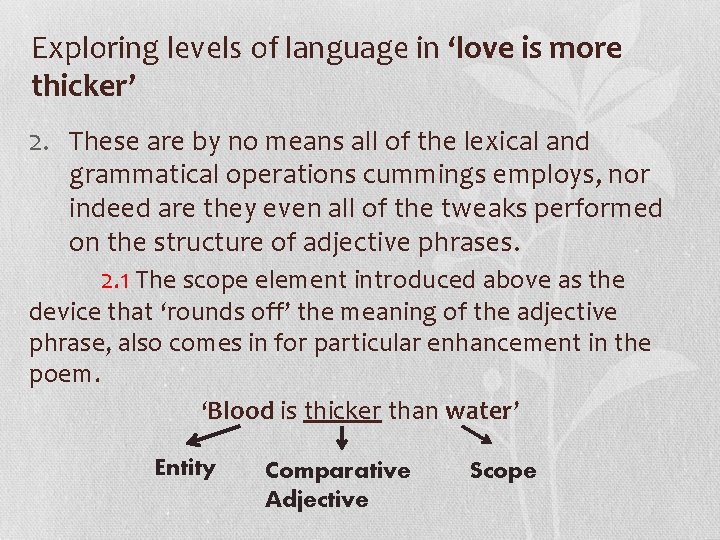

Exploring levels of language in ‘love is more thicker’ 2. These are by no means all of the lexical and grammatical operations cummings employs, nor indeed are they even all of the tweaks performed on the structure of adjective phrases. 2. 1 The scope element introduced above as the device that ‘rounds off’ the meaning of the adjective phrase, also comes in for particular enhancement in the poem. ‘Blood is thicker than water’ Entity Comparative Adjective Scope

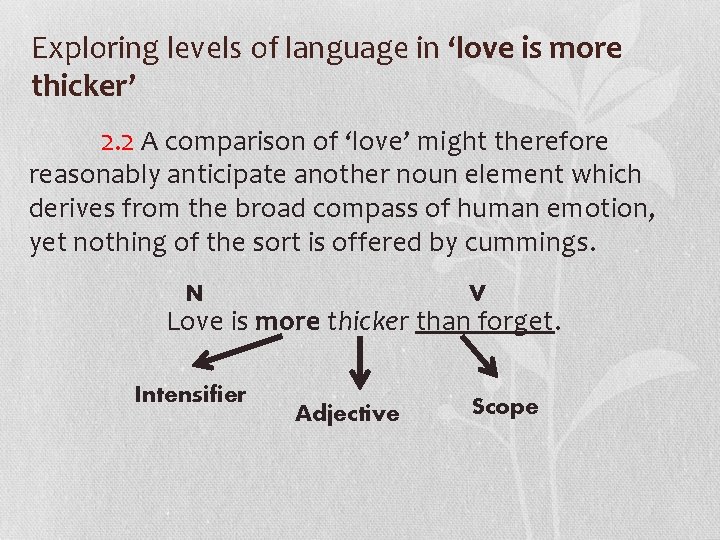

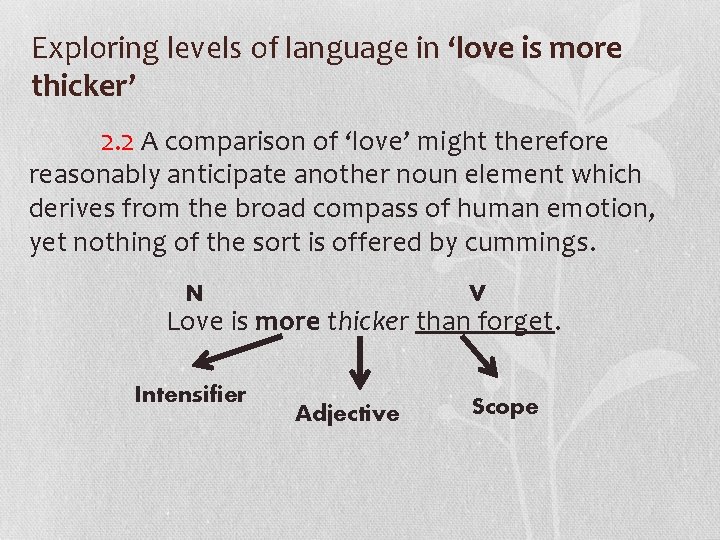

Exploring levels of language in ‘love is more thicker’ 2. 2 A comparison of ‘love’ might therefore reasonably anticipate another noun element which derives from the broad compass of human emotion, yet nothing of the sort is offered by cummings. V N Love is more thicker than forget. Intensifier Adjective Scope

Exploring levels of language in ‘love is more thicker’ 3. Cummings inserts adverbs of time-relationship, like ‘seldom’, ‘always’ or ‘never’, into the main slot in the adjective phrase frame. 4. Many of Cummings’ comparative and superlative structures are full blown logical tautologies simply because they replicate the basic premises of the proposition. ‘the sea is…deeper than the sea’ or ‘the sky is … higher than the sky’

Exploring levels of language in ‘love is more thicker’ 5. Other features embedded in the semantic fabric of the text include lexical antonyms, words of opposite meaning like the adjectives ‘thicker’ and ‘thinner’, the adverbs ‘never’ and ‘always’ and even the adjectival neologisms ‘sunly’ and ‘moonly’.

Stylistic analysis and interpretation The individual stylistic tactics used in the poem, replicated so vigorously and with such consistency, all drive towards the conclusion that love is, well, incomparable. Every search for a point of comparison encounters a tautology, a semantic anomaly or some kind of grammatical cul de sac. Love is at once more of something and less of it; not quite as absolute or certain as ‘always’ but still more than just ‘frequent’. It is deep, deeper even than the sea, and then a little bit deeper again.

Sentence Types The most ‘simple’ type of sentence structure is where the sentence comprises just one independent clause. Here are two sentences, each containing a single clause apiece: He ate his supper. He went to bed. (Simple Sentence) No formal linkage which are the so called conjunctions.

Sentence Types I tried to examine myself. I felt my pulse. I could not at first feel any pulse at all. Then, all of a sudden, it seemed to start off. I pulled out my watch and timed it. I made it a hundred and forty-seven to the minute. I tried to feel my heart. I could not feel my heart. It had stopped beating. -Jerome K. Jerome’s novel Three Men in a Boat

Sentence Types Compound Sentence is used to describe structures which have more than one clause in them, and where these clauses are of equal grammatical status. Compound sentences are built up through the technique of coordination and they rely on a fixed set of coordinating conjunctions like and, or, but, so, for, and yet. 1. He ate his supper and he went to bed. 2. He ate his supper so he went to bed. 3. He ate his supper but he went to bed shortly after. +

Sentence Types Compound Sentence Examples: • He huffed and he puffed and he blew the house down. • They sat on the terrace and many of the fishermen made fun of the old man and he was not angry.

Sentence Types Complex Sentence Involves two possible structural configurations, but their main informing principles is that the clauses they contain are in an asymmetrical relationship to one another. The first configuration involves subordination where the subordinate clause is appended to a main clause. To form this pattern, subordinating conjunctions are used and these include when, although, if, because and since. Examples: When he had eaten his supper, he went to bed. Although he had just eaten his supper, he went to bed.

Sentence Types Complex Sentence Subordination Embedding of one structure inside another. Ex: Mario realized he had eaten his supper. He announced that he had gone to bed.

Trailing Constituents and Anticipatory Constituents Trailing Constituents is the term used in stylistics for units which follow the Subject and Predicator in this way. Ex: Creeps in this petty pace from day to day. Anticipatory Constituents the reverse technique, where Adjuncts and subordinate clauses are placed before the main Subject-Predicator matrix. Ex: And when I turned my head to take a parting glance, I saw the straight line of the flat shore…

Illustrating grammar in action: Dicken’s famous fog (1) Fog everywhere. (2) Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping, and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. (3) Fog on the Essex Marshes, fog on the Kentish heights. (4) Fog creeping into the cabooses of collier-brigs; fog lying out on the yards, and hovering in the rigging of great ships; fog drooping on the gunwales of barges and small boats. (5) Fog in the eyes and throats of ancient Greenwich pensioners, wheezing by the firesides of their wards; fog in the stem and bowl of the afternoon pipe of the wrathful skipper, down in his close cabin; fog cruelly pinching the toes and gingers of his shivering little ‘prentice boy on deck. (6) Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all around them as if they were up in a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.

Illustrating grammar in action: Dicken’s famous fog Feature 1 A key stylistic feature is the way the central noun ‘fog’ is elaborated 9 or perhaps more accurately, ‘unelaborated’) throughout the passage. It is a resource of grammar that nouns commonly enter into combinations with other words so that any particular or special quality they possess can be identified and picked out.

Illustrating grammar in action: Dicken’s famous fog Feature 2 A popular interpretation of this passage is to see it as a text with ‘no verbs’. This is not strictly accurate, however, because only in the first three sentences and in part of sentence (5) have verbs been excised completely.

Illustrating grammar in action: Dicken’s famous fog Feature 3 A popular interpretation of this passage is to see it as a text with ‘no verbs’. This is not strictly accurate, however, because only in the first three sentences and in part of sentence (5) have verbs been excised completely.