Lets Talk Crosscultural Communication Skills for Interpreters and

- Slides: 108

Let’s Talk Cross-cultural Communication Skills for Interpreters and Providers Presented by: Marlene V. Obermeyer, MA, RN International Medical Interpreters Association Conference October 10, 2009 Marlene V. Obermeyer

To play the slideshow with sound: n n n Download the file to your hard drive Click on Slideshow – VIEW Show Click on mouse to advance to the next slide

"Seek first to understand, then to be understood. " — Stephen R. Covey

Learning Objectives: n n Explain cross-cultural communication concepts and apply them to the interpreter-patient-provider triad. Discuss how the intersection of the provider’s culture, the patient’s culture, and the Western U. S. culture affect the communication process. n Explain how to identify, prevent, and correct the most common interpretation errors. n Demonstrate effective cross-cultural communication skills in the interpreter-patient-provider triad.

Introductions n n n Who we are Five Introductions: Group Work Group Rules

Our Rules* n n n You have the right to a personal level of disclosure. You can say as little or as much as you wish about yourself. There are no right or wrong answers. There are no right or wrong questions. There should be no risk to your cultural identify. Pride in one's own identity is essential, as long as this pride does not exclude or deny others their differences. Self-awareness is a wonderful gift although sometimes a painful one. *Adapted from: www. llas. ac. uk/resources/paper/1303

Life is like playing a violin in public and learning the instrument as one goes on. Samuel Butler Music: Salut D'amour http: //www. amazon. com/gp/product/B 0011 VIBC 6/ref=dm_sp_adp Sarah Chang Selections Sampler at Amazon. com downloads

The Communication Process n n True or False A Brief History of Communication

From Drumbeats to Bandwidth

Hieroglyphic writing

The First Telegraphs

776 BC: Homing pigeons used to announce the outcome of the Olympic Games to the Athenians .

Roman Mail

12 th Century Printing

Gutenberg press 1452

1840 s – Telegraph Samuel Morse

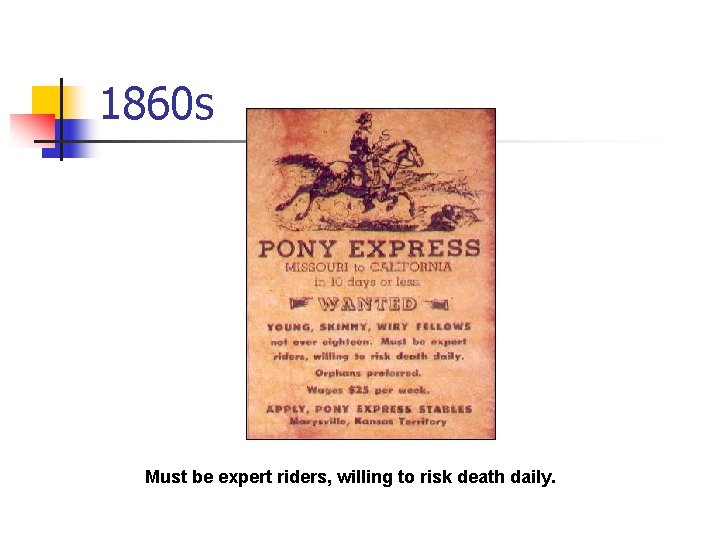

1860 s Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily.

1870 s

1910 - Radio

Telephone

1950 s First Computers

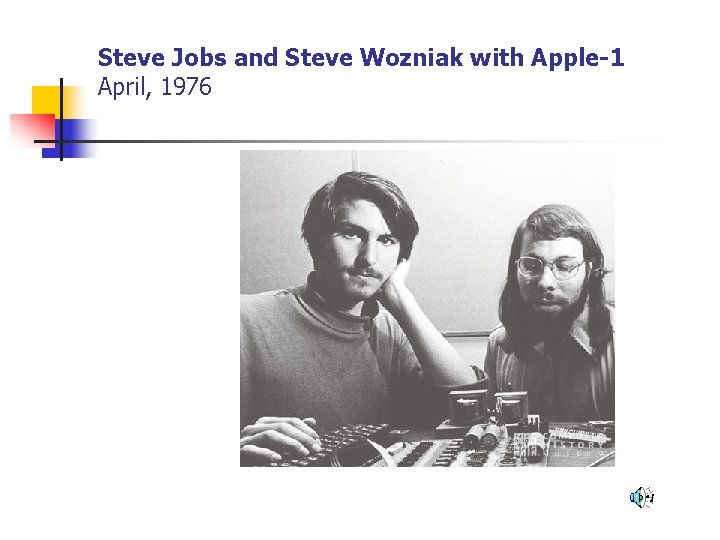

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak with Apple-1 April, 1976

Microsoft 1978

n 1991 - World-Wide Web (WWW) developed by Tim Berners-Lee

Exercise: Saying “Yes. ” n n Volunteers Discussion

http: //devanperona. blogspot. com/2007/02/communication. html

Communication n What is communication?

Group Exercise n n Forms of communication Discussion

Root words n n Latin “Com” (with or together) “Unio” (union) The ancients believed that engaging in communication in some mysterious way a commonality or true union was achieved. Involves the ability to use symbols to create meaning.

Language n “Symbolic language then allows for all of the features that make us distinctively human. ” Dr. Nancy Murphy, ethicist

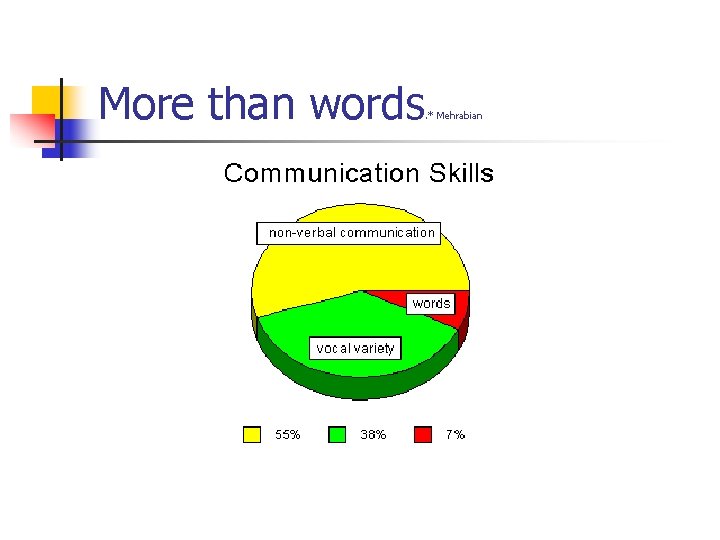

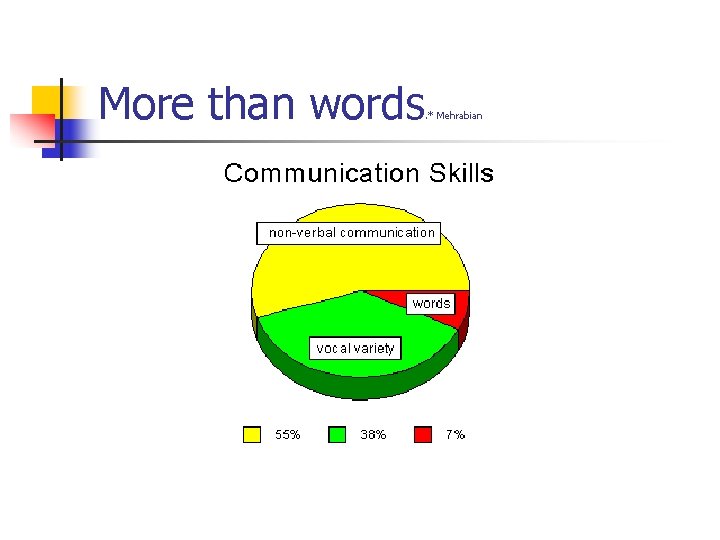

More than words . * Mehrabian

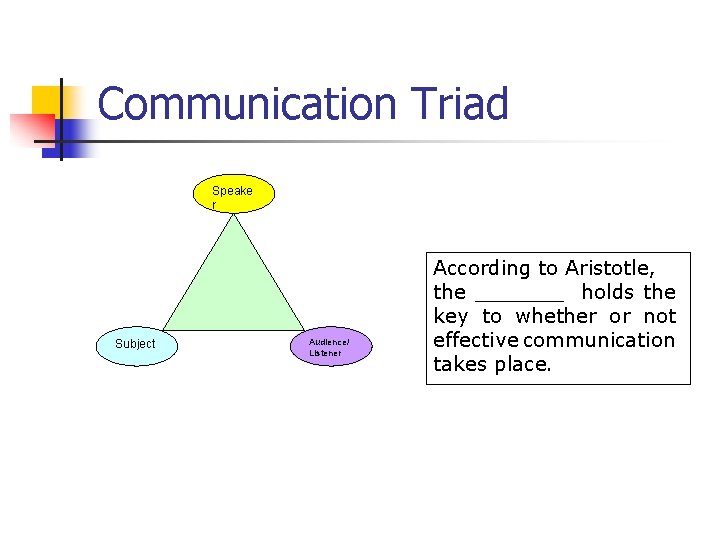

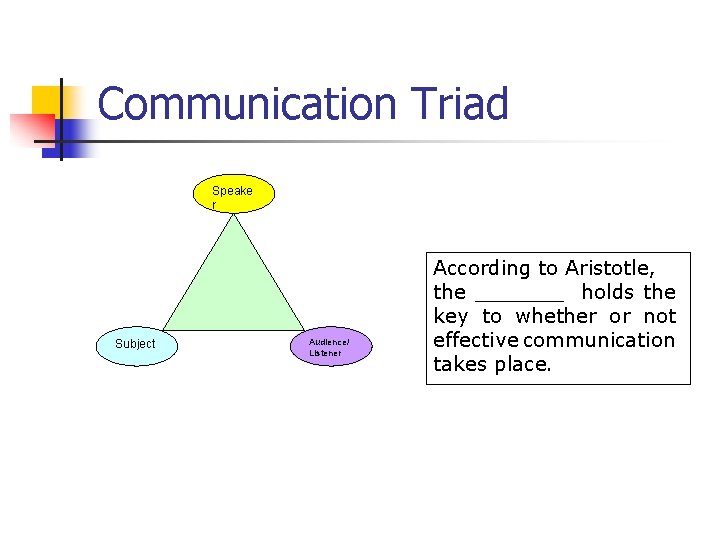

Communication Triad Speake r Subject Audience/ Listener According to Aristotle, the _______ holds the key to whether or not effective communication takes place.

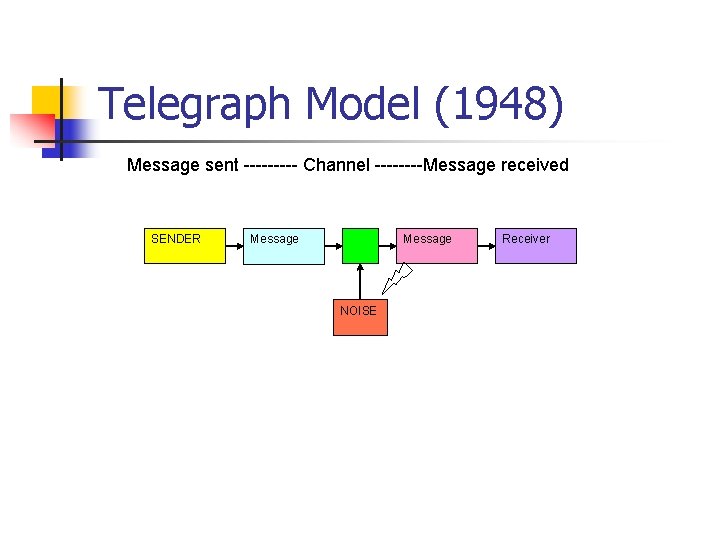

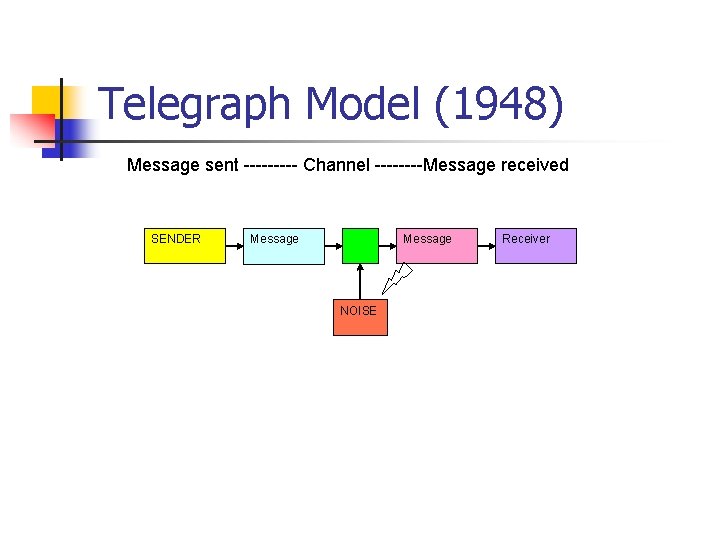

Telegraph Model (1948) Message sent ----- Channel ----Message received SENDER Message NOISE Receiver

Elements of communication n n n Speaker Listener Message Noise Channel Feedback

n communication is a process in which a person, through the use of signs (natural, universal)/symbols (by human convention), verbally and/or non verbally, conveys meaning to another in order to achieve a common goal.

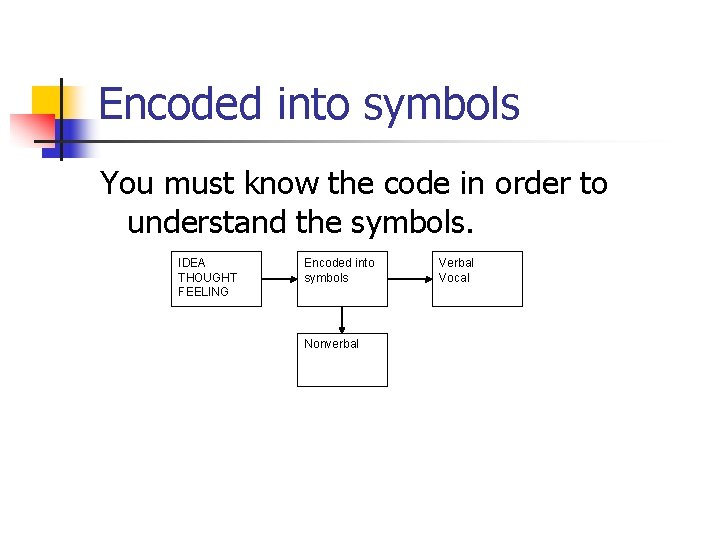

Encoded into symbols You must know the code in order to understand the symbols. IDEA THOUGHT FEELING Encoded into symbols Nonverbal Vocal

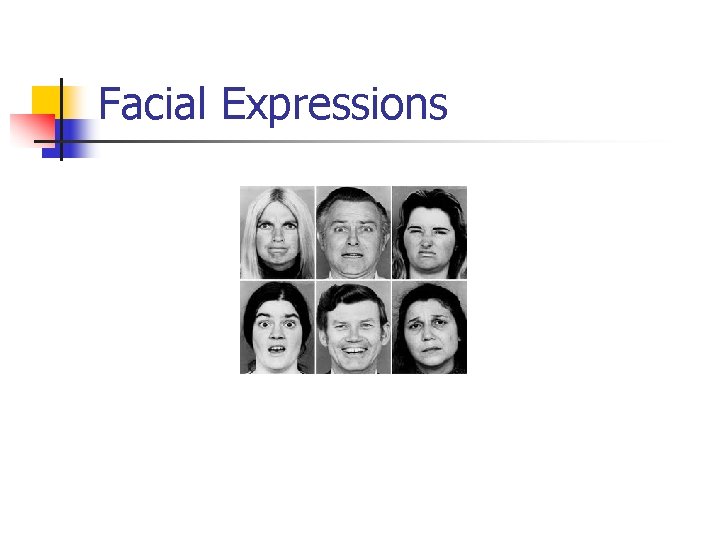

Facial Expressions

n Next to words, the human face is the primary source of information for determining an individual/s internal feelings. * http: //www. bartneck. de/workshop/chi 2006/papers/chatting_chif 06. pdf http: //www. apa. org/monitor/jan 00/sc 1. html

Posture and Gestures

Personal Space

Formality

The secret languge

Greetings

Eye Contact n n n Research shows that a speaker who looks at an audience is perceived as much more Confident Credible Qualified Honest

Haptics n High Contact vs Low Contact Cultures n Average number of touches per hour in San Juan, Puerto Rico = 180 In Paris = 100 In Gainesville, Fla = 2 In London = 0 n (S. Jourard research) n n Men and women: Japanese and Americans = allow touching between women, but not tolerated between men. n High touch cultures include Italian and Greek cultures. n n n *http: //www. cba. uni. edu/buscomm/nonverbal/Culture. htm http: //cjhp. org/Volume 6 -2008/issue 1/tomita. pdf

Haptics

“The body says what words cannot. ” Martha Graham, Choreographer

What does it mean?

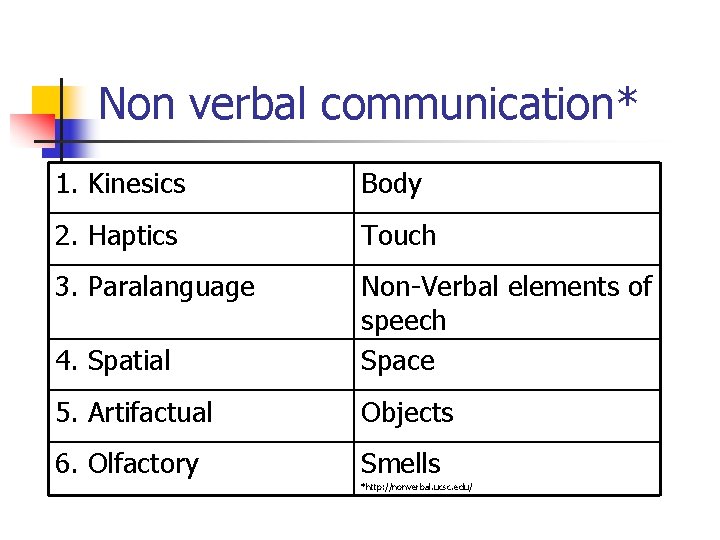

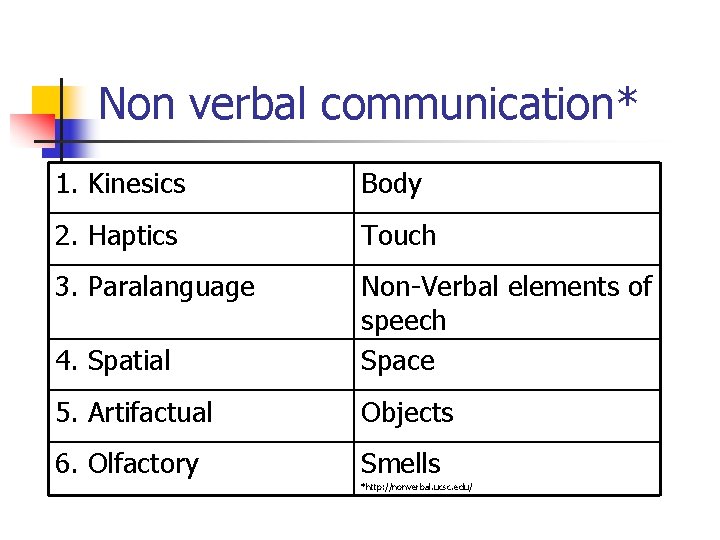

Non verbal communication* 1. Kinesics Body 2. Haptics Touch 3. Paralanguage 4. Spatial Non-Verbal elements of speech Space 5. Artifactual Objects 6. Olfactory Smells *http: //nonverbal. ucsc. edu/

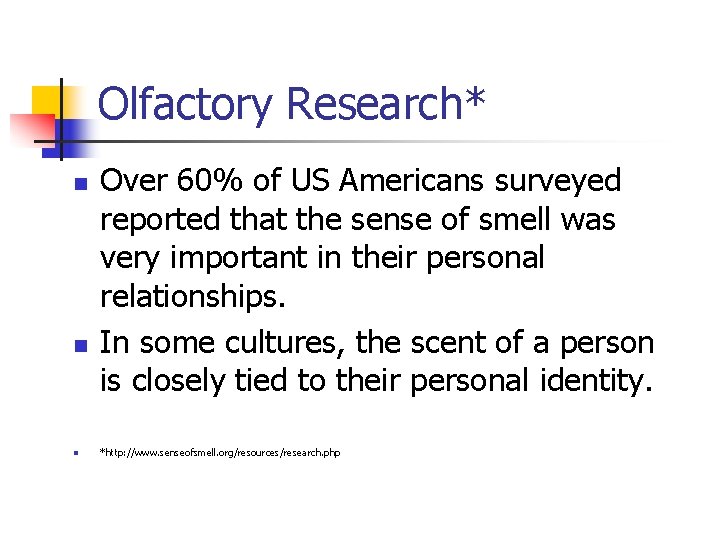

Olfactory Research* n n n Over 60% of US Americans surveyed reported that the sense of smell was very important in their personal relationships. In some cultures, the scent of a person is closely tied to their personal identity. *http: //www. senseofsmell. org/resources/research. php

Time as Communication

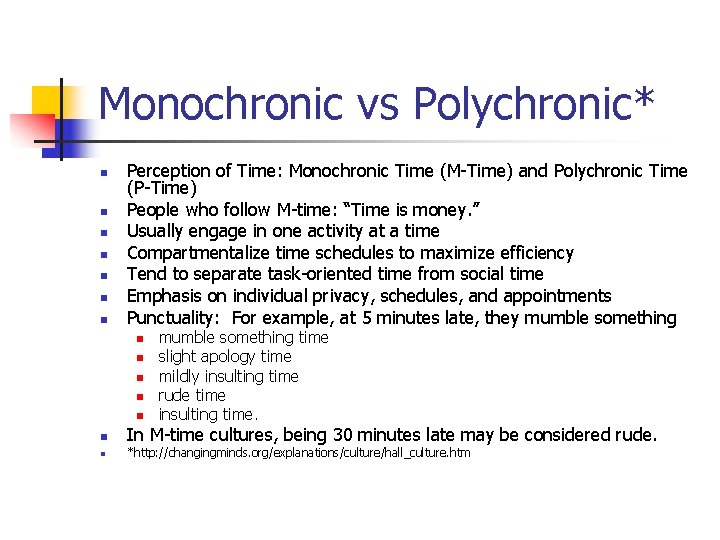

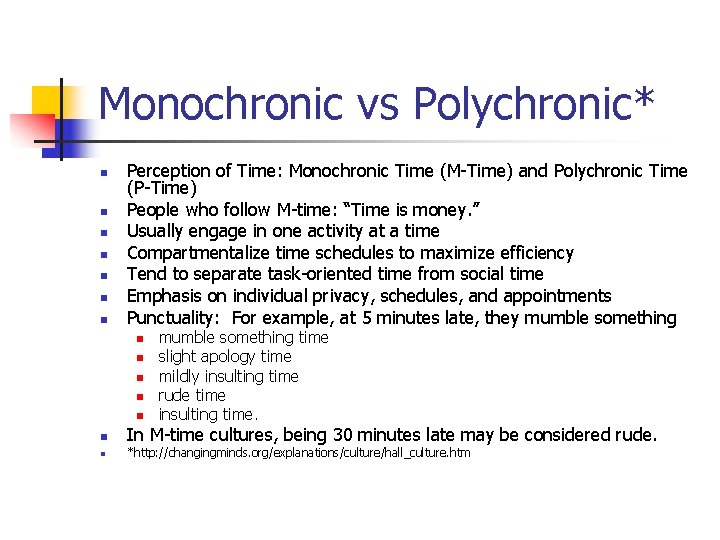

Monochronic vs Polychronic* n n n n Perception of Time: Monochronic Time (M-Time) and Polychronic Time (P-Time) People who follow M-time: “Time is money. ” Usually engage in one activity at a time Compartmentalize time schedules to maximize efficiency Tend to separate task-oriented time from social time Emphasis on individual privacy, schedules, and appointments Punctuality: For example, at 5 minutes late, they mumble something n n n n mumble something time slight apology time mildly insulting time rude time insulting time. In M-time cultures, being 30 minutes late may be considered rude. *http: //changingminds. org/explanations/culture/hall_culture. htm

Direct vs Indirect

Paralanguage* n n n Paralanguage (sometimes called vocalics) is the study of nonverbal cues of the voice. Various acoustic properties of speech such as tone, pitch and accent, can all give off nonverbal cues. Paralanguage may change the meaning of words. *http: //atc. bentley. edu/faculty/wb/presentations/paralanguage/ppframe. htm

Level 1: Message sent = Message received

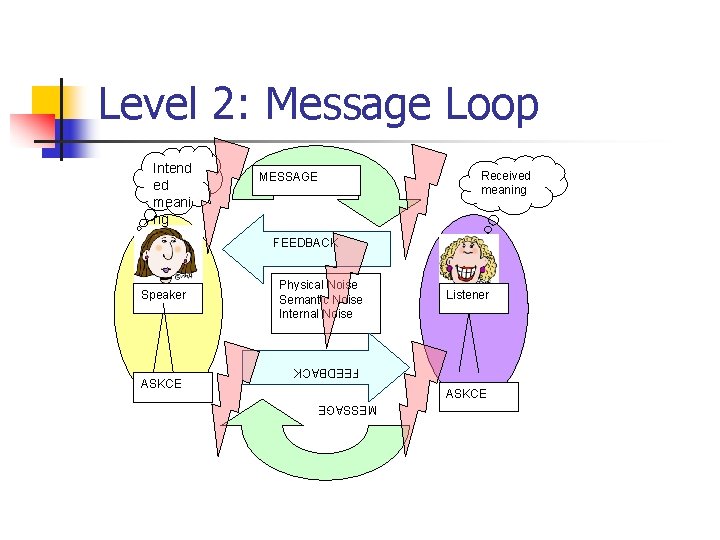

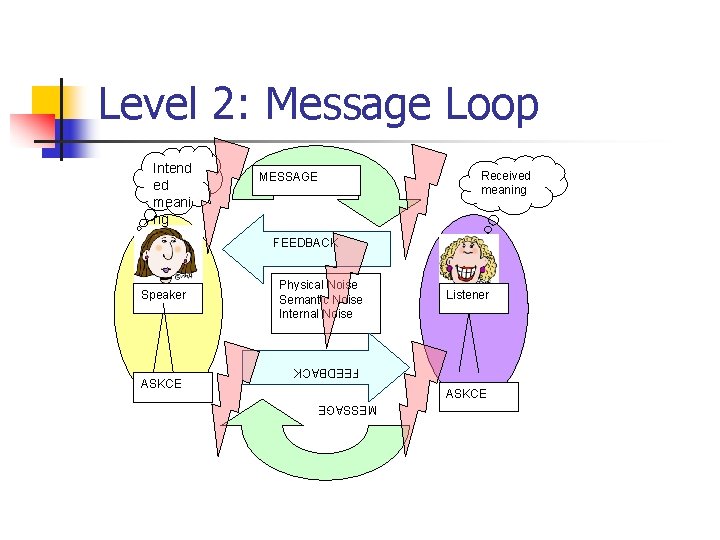

Level 2: Message Loop Intend ed meani ng MESSAGE Received meaning FEEDBACK Listener ASKCE MESSAGE ASKCE Physical Noise Semantic Noise Internal Noise FEEDBACK Speaker

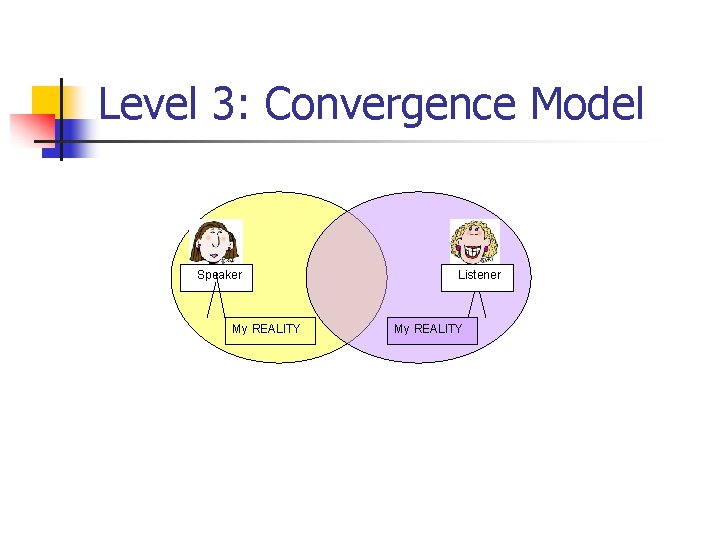

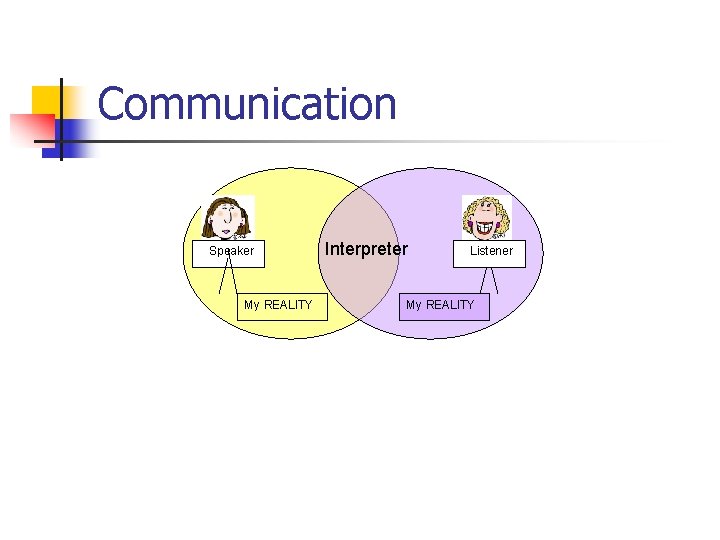

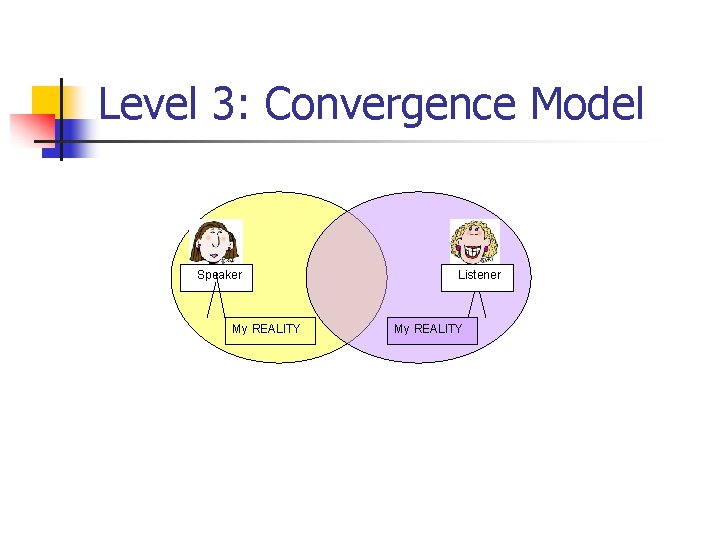

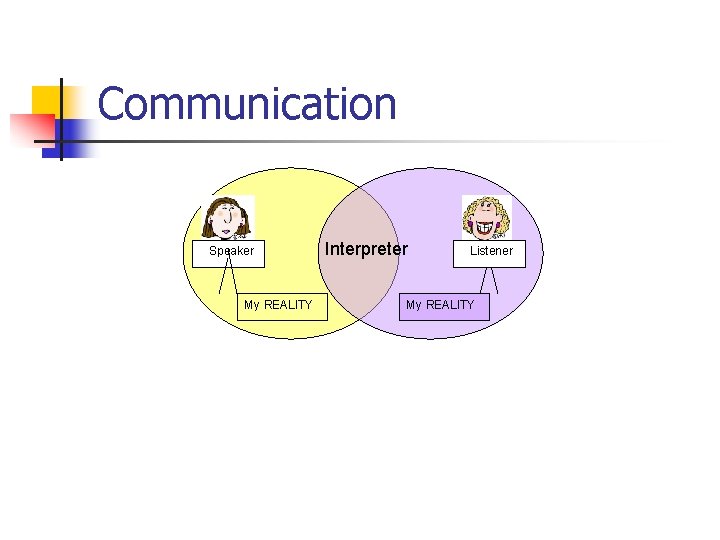

Level 3: Convergence Model Speaker My REALITY Listener My REALITY

The Interpreting Process n n n Level 1 Level 2 Level 3

Communication Real communication occurs when we listen with understanding - to see the idea and attitude from the other person's point of view, to sense how it feels to them, to achieve their frame of reference in regard to the thing they are talking about. " Carl Rogers

The Accident

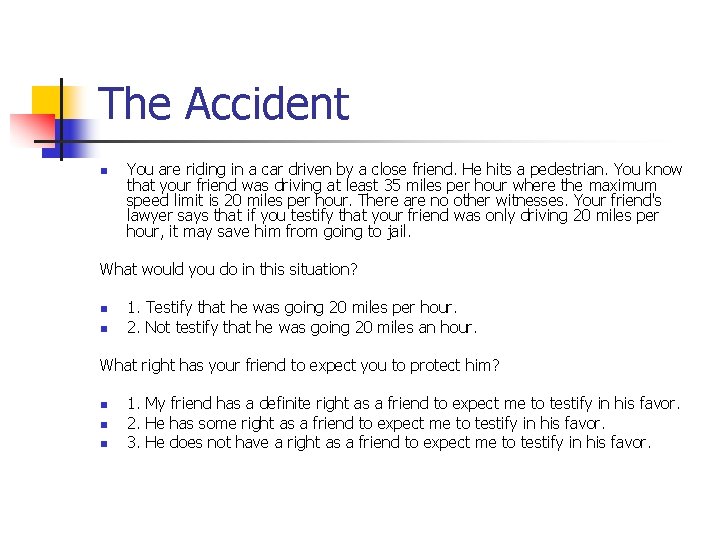

The Accident n You are riding in a car driven by a close friend. He hits a pedestrian. You know that your friend was driving at least 35 miles per hour where the maximum speed limit is 20 miles per hour. There are no other witnesses. Your friend's lawyer says that if you testify that your friend was only driving 20 miles per hour, it may save him from going to jail. What would you do in this situation? n n 1. Testify that he was going 20 miles per hour. 2. Not testify that he was going 20 miles an hour. What right has your friend to expect you to protect him? n n n 1. My friend has a definite right as a friend to expect me to testify in his favor. 2. He has some right as a friend to expect me to testify in his favor. 3. He does not have a right as a friend to expect me to testify in his favor.

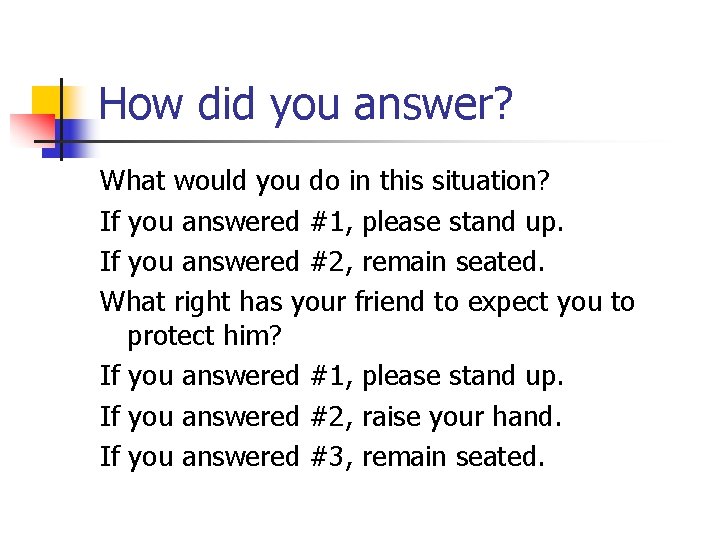

How did you answer? What would you do in this situation? If you answered #1, please stand up. If you answered #2, remain seated. What right has your friend to expect you to protect him? If you answered #1, please stand up. If you answered #2, raise your hand. If you answered #3, remain seated.

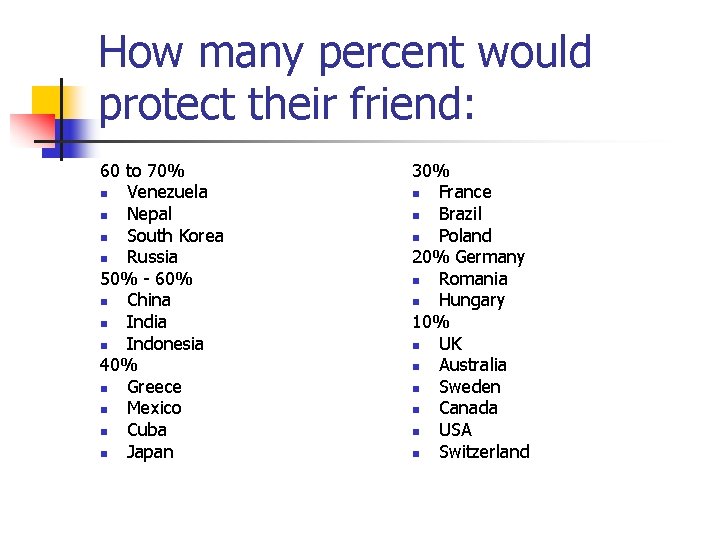

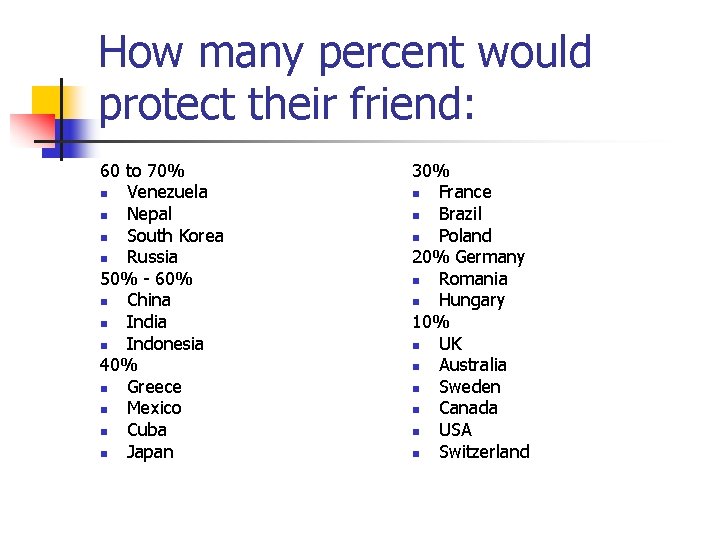

How many percent would protect their friend: 60 to 70% n Venezuela n Nepal n South Korea n Russia 50% - 60% n China n India n Indonesia 40% n Greece n Mexico n Cuba n Japan 30% n France n Brazil n Poland 20% Germany n Romania n Hungary 10% n UK n Australia n Sweden n Canada n USA n Switzerland

Corruption versus loyalty? n Particularist: logic of the heart and human friendship. Universalist: logic of truth and the law. n *http: //www. well. com/user/art/s%2 Bb 22001 cm. html n

What is culture? n n What you see What you do not see

When you think of U. S. Americans… n n n What do you think of? Perception – Interpretation – Evaluation Examples

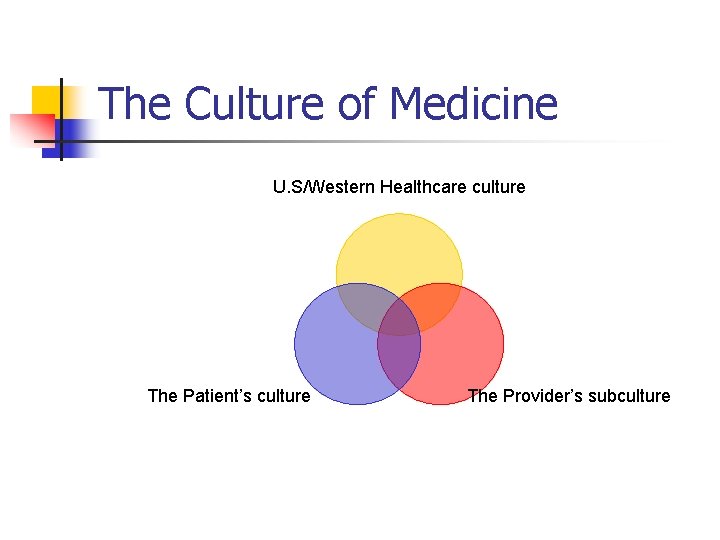

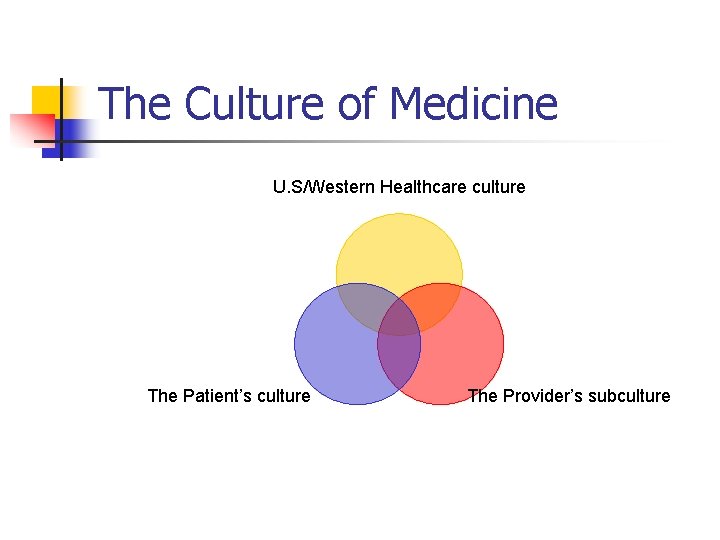

The Culture of Medicine U. S/Western Healthcare culture The Patient’s culture The Provider’s subculture

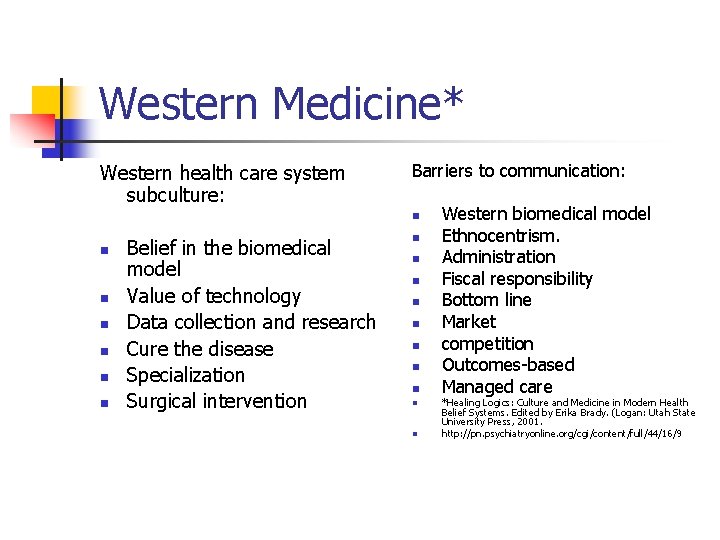

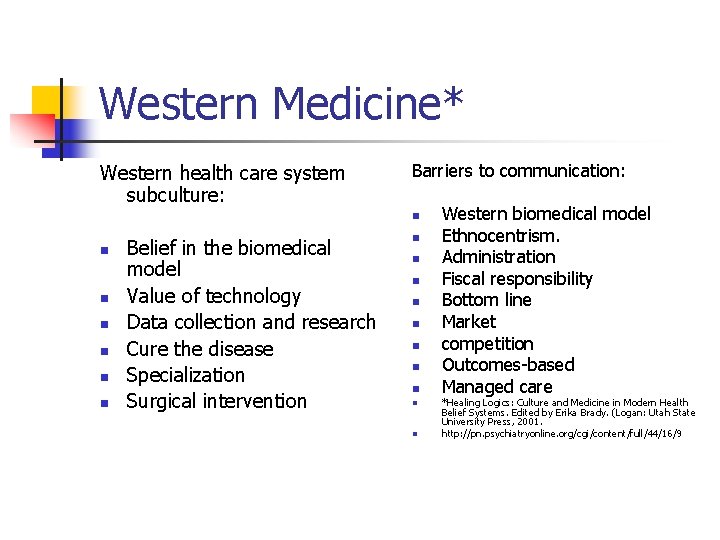

Western Medicine* Western health care system subculture: Barriers to communication: n n n n Belief in the biomedical model Value of technology Data collection and research Cure the disease Specialization Surgical intervention n n Western biomedical model Ethnocentrism. Administration Fiscal responsibility Bottom line Market competition Outcomes-based Managed care *Healing Logics: Culture and Medicine in Modern Health Belief Systems. Edited by Erika Brady. (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2001. http: //pn. psychiatryonline. org/cgi/content/full/44/16/9

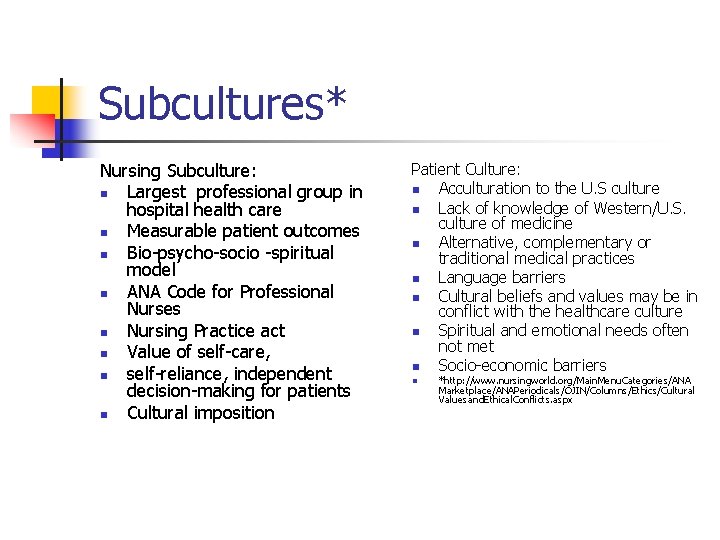

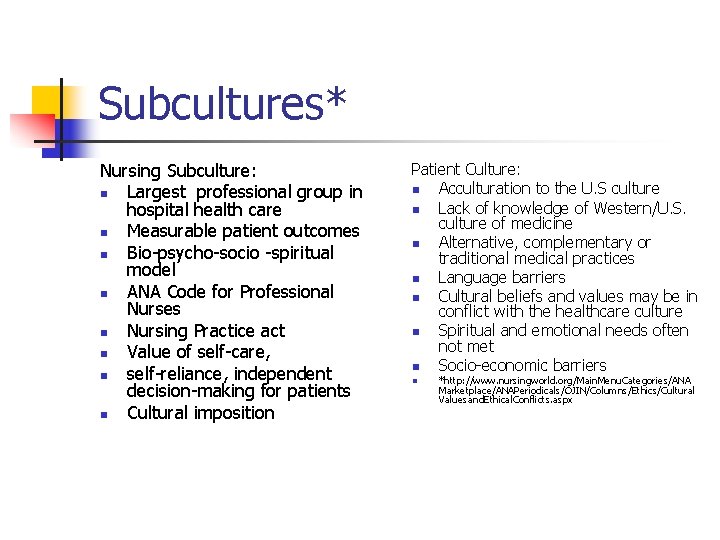

Subcultures* Nursing Subculture: n Largest professional group in hospital health care n Measurable patient outcomes n Bio-psycho-socio -spiritual model n ANA Code for Professional Nurses n Nursing Practice act n Value of self-care, n self-reliance, independent decision-making for patients n Cultural imposition Patient Culture: n Acculturation to the U. S culture n Lack of knowledge of Western/U. S. culture of medicine n Alternative, complementary or traditional medical practices n Language barriers n Cultural beliefs and values may be in conflict with the healthcare culture n Spiritual and emotional needs often not met n Socio-economic barriers n *http: //www. nursingworld. org/Main. Menu. Categories/ANA Marketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/Columns/Ethics/Cultural Valuesand. Ethical. Conflicts. aspx

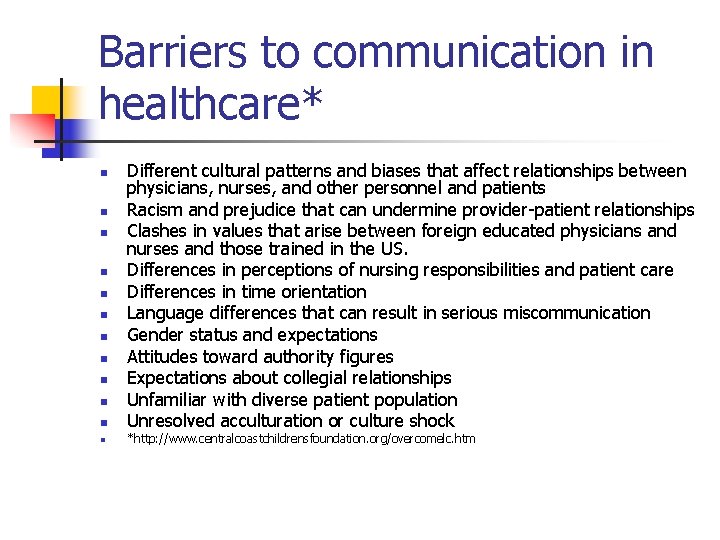

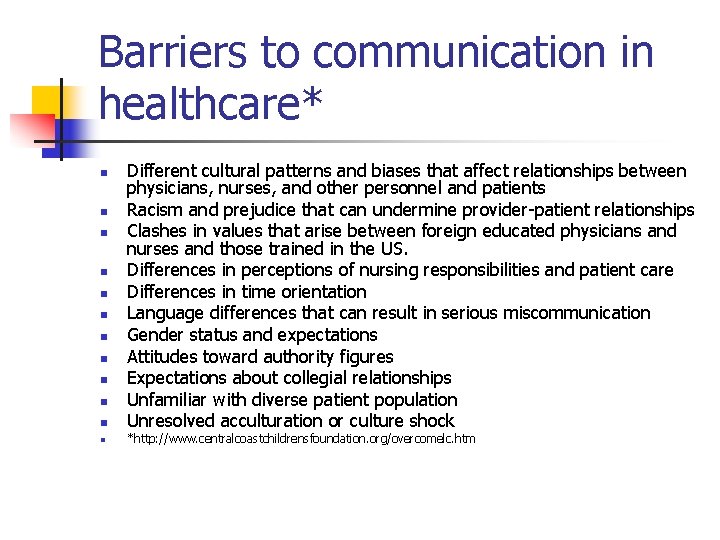

Barriers to communication in healthcare* n n n Different cultural patterns and biases that affect relationships between physicians, nurses, and other personnel and patients Racism and prejudice that can undermine provider-patient relationships Clashes in values that arise between foreign educated physicians and nurses and those trained in the US. Differences in perceptions of nursing responsibilities and patient care Differences in time orientation Language differences that can result in serious miscommunication Gender status and expectations Attitudes toward authority figures Expectations about collegial relationships Unfamiliar with diverse patient population Unresolved acculturation or culture shock *http: //www. centralcoastchildrensfoundation. org/overcomelc. htm

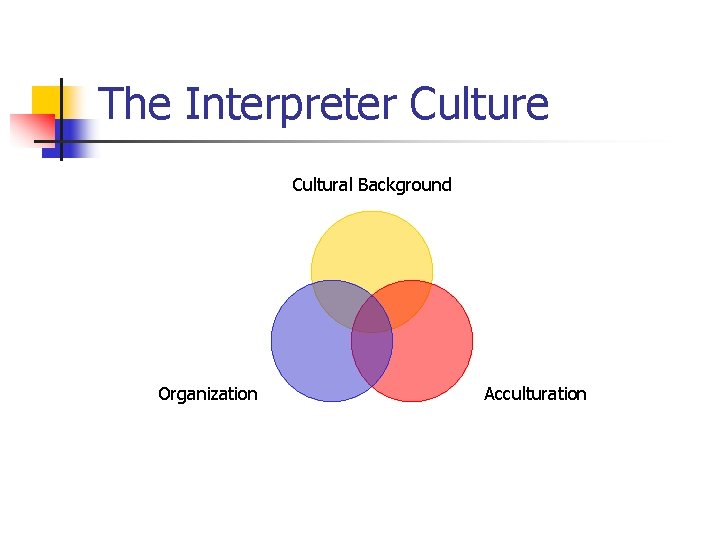

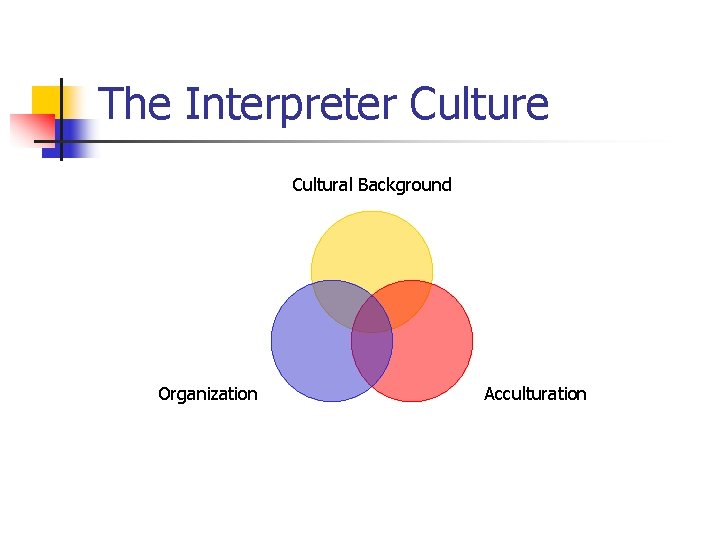

The Interpreter Culture Cultural Background Organization Acculturation

Your culture n n How did you introduce yourself? What are important to you? What are your most important values? Ethnicity, education, socio-economic status

Ethnicity and acculturation n Can you think of some stereotypical images people have of your cultural or ethnic group? Write a list. n Are they generally positive or negative images? n n n Do you feel that some of the images are true for everyone in your cultural group? If they are not which group would be exempt from these stereotypes? How acculturated are you into the U. S. culture? What language do you speak at home? What foods do you eat? How do you dress? Are you comfortable with your cultural identity?

Your organization n n Who do you work for? What is their mission? What are their values? What are you responsible for? Policies and procedures

Group Discussion n n n Scenarios Choose a spokesperson for the group Choose a timekeeper Identify the communication/cultural barriers Identify the communication errors. Identify the interpretation errors. Demonstrate Before and After

n n Errors in Medical Interpretation and Their Potential Clinical Consequences in Pediatric Encounters By Glenn Flores, MD*, et al

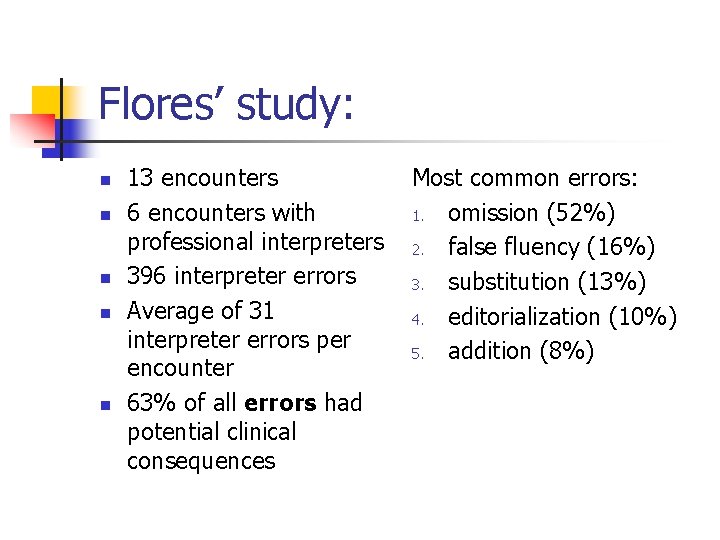

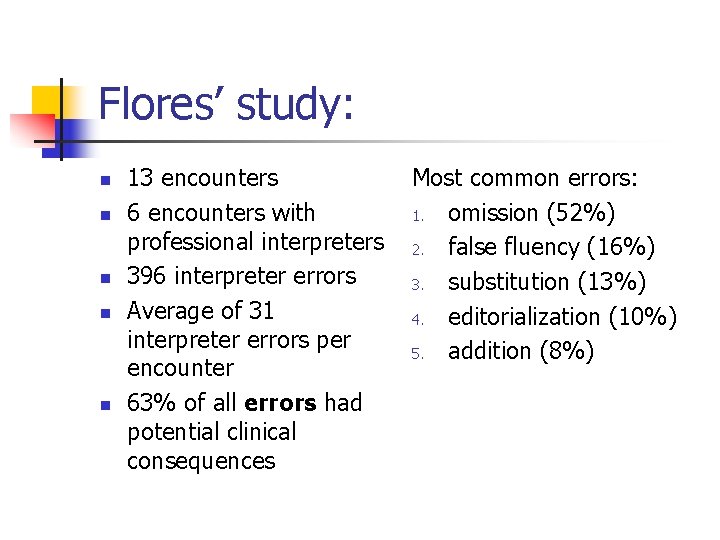

Flores’ study: n n n 13 encounters 6 encounters with professional interpreters 396 interpreter errors Average of 31 interpreter errors per encounter 63% of all errors had potential clinical consequences Most common errors: 1. omission (52%) 2. false fluency (16%) 3. substitution (13%) 4. editorialization (10%) 5. addition (8%)

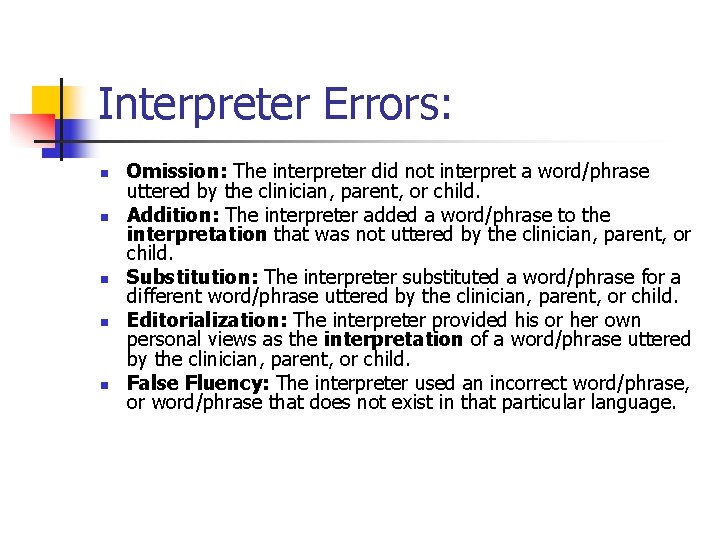

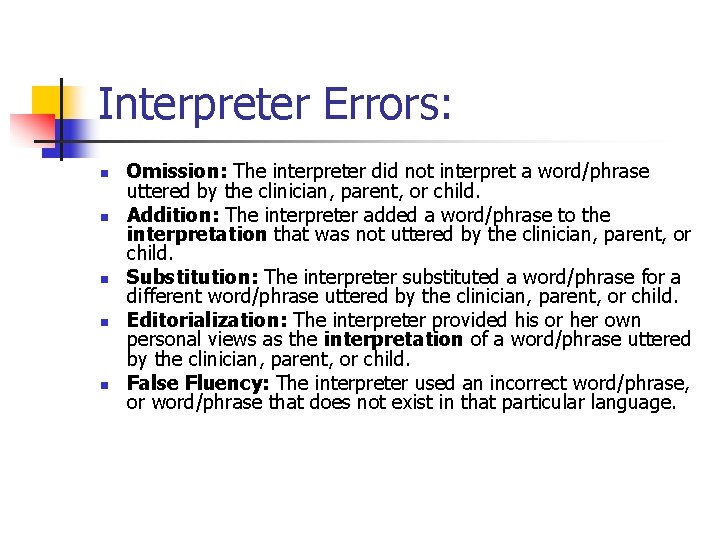

Interpreter Errors: n n n Omission: The interpreter did not interpret a word/phrase uttered by the clinician, parent, or child. Addition: The interpreter added a word/phrase to the interpretation that was not uttered by the clinician, parent, or child. Substitution: The interpreter substituted a word/phrase for a different word/phrase uttered by the clinician, parent, or child. Editorialization: The interpreter provided his or her own personal views as the interpretation of a word/phrase uttered by the clinician, parent, or child. False Fluency: The interpreter used an incorrect word/phrase, or word/phrase that does not exist in that particular language.

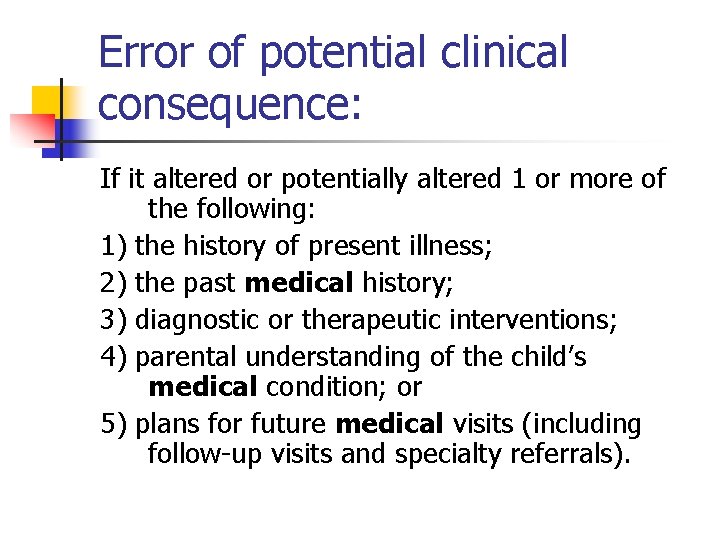

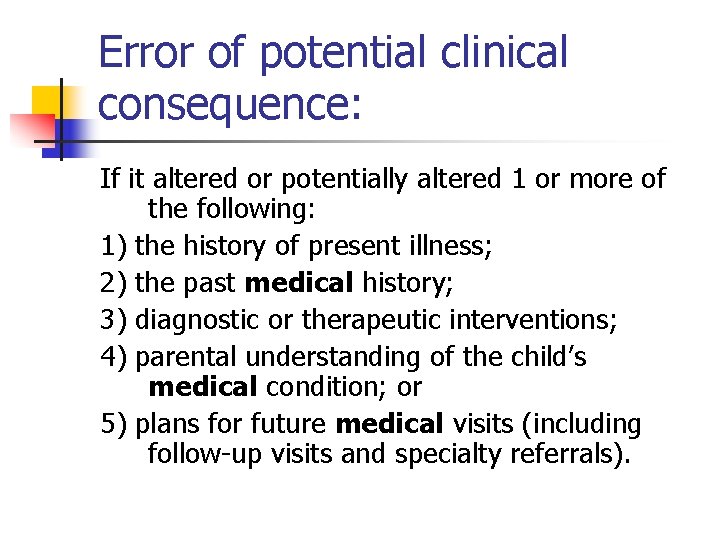

Error of potential clinical consequence: If it altered or potentially altered 1 or more of the following: 1) the history of present illness; 2) the past medical history; 3) diagnostic or therapeutic interventions; 4) parental understanding of the child’s medical condition; or 5) plans for future medical visits (including follow-up visits and specialty referrals).

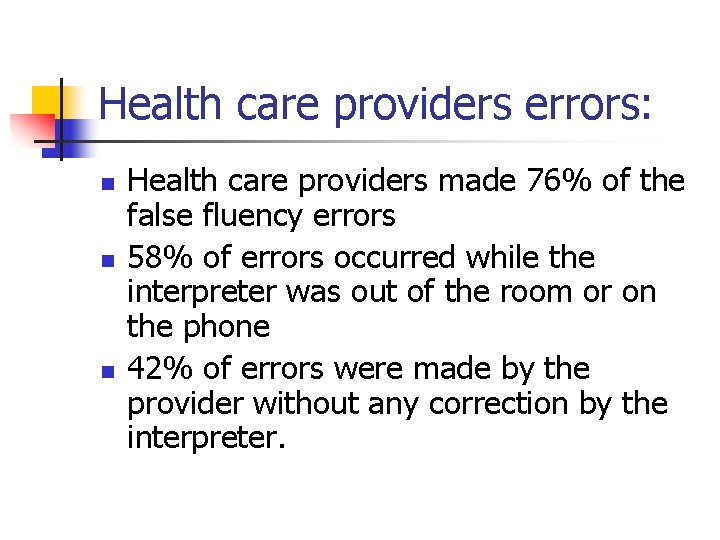

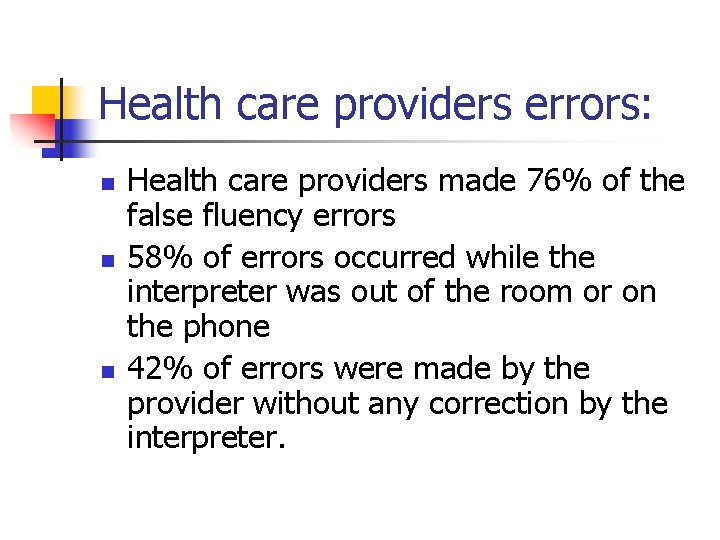

Health care providers errors: n n n Health care providers made 76% of the false fluency errors 58% of errors occurred while the interpreter was out of the room or on the phone 42% of errors were made by the provider without any correction by the interpreter.

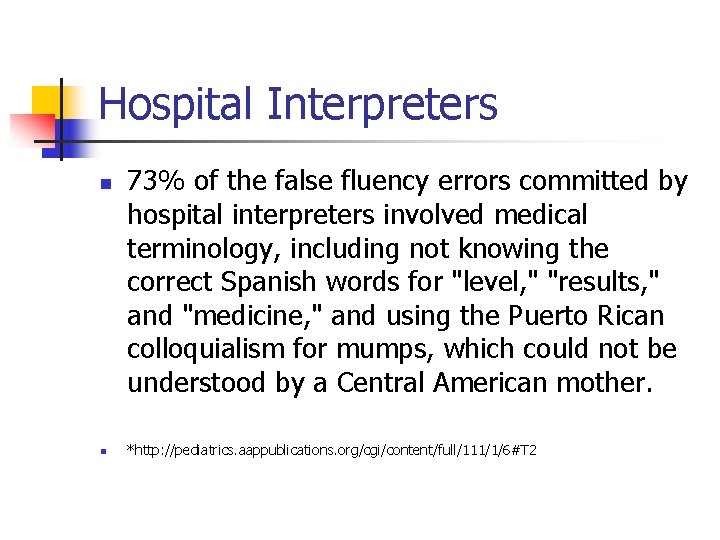

Hospital Interpreters n n 73% of the false fluency errors committed by hospital interpreters involved medical terminology, including not knowing the correct Spanish words for "level, " "results, " and "medicine, " and using the Puerto Rican colloquialism for mumps, which could not be understood by a Central American mother. *http: //pediatrics. aappublications. org/cgi/content/full/111/1/6#T 2

Interpreters n n There was no statistically significant difference between hospital and ad hoc interpreters in the mean number of errors committed per encounter. Although errors made by hospital interpreters were significantly less likely to be of potential clinical consequence than those made by ad hoc interpreters, over half of hospital interpreter errors had potential clinical consequences.

n n “We may have different religions, different languages, different colored skin, but we all belong to one human race. ” Kofi Annan

Group Discussion n n n Scenarios Choose a spokesperson for the group Choose a timekeeper Identify the communication/cultural barriers Identify the communication errors. Identify the interpretation errors. Demonstrate Before and After (Provider. Interpreter-Patient)

Presentations n n Group Presentations Discussion

A Medical Encounter n Personal Story

“If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart. ” Nelson Mandela

Communication Speaker My REALITY Interpreter Listener My REALITY

The Role of the Interpreter

Communication Real communication occurs when we listen with understanding - to see the idea and attitude from the other person's point of view, to sense how it feels to them, to achieve their frame of reference in regard to the thing they are talking about. " Carl Rogers

If music is played, immediately the heart of the music enters into my heart, or my heart enters into the music. At that time, we do not need outer communication; the inner communion of the heart is enough. My heart is communing with the heart of the music and in our communion we become inseparably one. Samuel Butler

To contact me: n n n Marlene Obermeyer director@culture-advantage. com interpreter. program@yahoo. com 620 -382 -6934 http: //www. cultureadvantage. org/ http: //www. culture-advantage. com IMIA Kansas State Representative: Always use a qualified interpreter.

Selected Online References n n n n n www. llas. ac. uk/resources/paper/1303 Mehrabian's site: http: //www. kaaj. com/psych/ http: //www. cba. uni. edu/buscomm/nonverbal/Culture. htm http: //cjhp. org/Volume 6 -2008/issue 1/tomita. pdf http: //www. senseofsmell. org/resources/research. php http: //www. blackwellreference. com/public/tocnode? id=g 9780631233176_chunk_g 978063123493711_ss 1 -1 http: //www. winadvisorygroup. com/High-context. Low-context. html http: //atc. bentley. edu/faculty/wb/presentations/paralanguage/ppframe. htm http: //www. well. com/user/art/s%2 Bb 22001 cm. html http: //changingminds. org/explanations/culture/hall_culture. htm http: //www. senseofsmell. org/resources/research. php http: //changingminds. org/explanations/culture/hall_culture. htm http: //atc. bentley. edu/faculty/wb/presentations/paralanguage/ppframe. htm http: //www. well. com/user/art/s%2 Bb 22001 cm. html http: //pn. psychiatryonline. org/cgi/content/full/44/16/9 http: //www. nursingworld. org/Main. Menu. Categories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/Columns/Ethics/ Cultural. Valuesand. Ethical. Conflicts. aspx http: //pediatrics. aappublications. org/cgi/content/full/111/1/6#T 2 Mehrabian's site: http: //www. kaaj. com/psych/ http: //culture-advantage. wikispaces. com/communication 101

Other References n n n n n n n Healing Logics: Culture and Medicine in Modern Health Belief Systems. Edited by Erika Brady. (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2001. Mehrabian, Albert, and Ferris, Susan R. “Inference of Attitudes from Nonverbal Communication in Two Channels, ” Journal of Consulting Psychology, Vol. 31, No. 3, June 1967, pp. 248 -258 Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent messages, Wadsworth, California: Belmont Mehrabian, A. (1972). Nonverbal communication. Aldine-Atherton, Illinois: Chicago Barclay, L. (2005). Patient Safety and Health Information Technology Conference: A Newsmaker Interview With Carolyn M. Clancy, MD Medscape Medical News. Retrieved from http: //www. medscape. com/viewarticle/506405 5/25/2008. American Holistic Nurses' Association. (2004). Position Statement on Holistic Nursing Ethics. Retrieved September 24, 2005 at: http: //www. ahncc. org/pages/1/index. htm. American Cultural Patterns: A Cross-Cultural Perspective, revised edition. Stewart, Edward and Bennett, Milton. 1991 Intercultural Press. Xu, Y. (2005). Clinical challenges of Asian nurses in a foreign health care environment. Home Health Care Management and Practice, 17(6), 492 -494. ARTFL Project, Webster Dictionary, 1913. Accessed October 7, 2006 at : http: //machaut. uchicago. edu/cgi-bin/WEBSTER. sh? WORD=communicate communication. (n. d. ). Dictionary. com Unabridged (v 1. 0. 1). Retrieved October 30, 2006, from Dictionary. com website: http: //dictionary. reference. com/browse/communication Richmond, V. P. , & Mc. Croskey, J. C. (1992). Nonverbal behavior in interpersonal relations (3 rd edition). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Kaminski, S. (2003). S. Kaminski’s Online Resources. Accessed October 7, 2006 at: http: //www. shkaminski. com/Classes/Readings/Task%20 Force%205%20 Final. htm Bandwidth. (2006) Encarta® World English Dictionary [North American Edition] © & (P)2006. Retrieved October 30, 2006 at: http: //encarta. msn. com/dictionary_1861588703/bandwidth. html Griffin, E. (1997). A First Look at Communication theory (3 rd ed. ), Mc. Graw-Hill, . information theory. (n. d. ). The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 30, 2006, from Reference. com website: http: //www. reference. com/browse/columbia/inform-th Underwood, Mike, (2003). Introductory Models and Concepts. Retrived online October 26, 2006 at: http: //www. cultsock. ndirect. co. uk/MUHome/cshtml/introductory/smcr. html C. Windley M. Skinner, (2006). http: //www. class. uidaho. edu/comm 101/chapters/selecting_topic 4. htm Figueroa, M. , Kincaid, L. , Rani, M. , Lewis, G. (2002). Communication for Social Change Working Paper Series. Retrieved online October 21, 2006 from: http: //www. comminit. com/strategicthinking/stcfscindicators/sld-1500. html Yates, D. (2006). Oral Communication. Retrieved online on October 26, 2006 from: http: // www. cultsock. ndirect. co. uk/MUHome/cshtml/index. html Hall, E. (1983). The Dance of Life: The Other Dimension of Time. New York: Doubleday/Anchor Books; Hall, E. (1966). The Hidden Dimension, Doubleday, Garden City, N. Y. Jourard, S. M. (1966). An exploratory study of body accessibility. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 5, 221 -231. Cited in Field, T. (1999). American Adolescents Touch Each Other Less And Are More Aggressive Toward Their Peers As Compared With French Adolescents Adolescence, Winter 1999. Retrieved online from http: //www. findarticles. com/p/articles/mi_m 2248/is_136_34/ai_59810232/pg_3. Trompenaars, F. (1995). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Thank you! Marlene Culture Advantage