Lesson 6 The Millers tale The Great chain

- Slides: 10

Lesson 6 The Miller’s tale

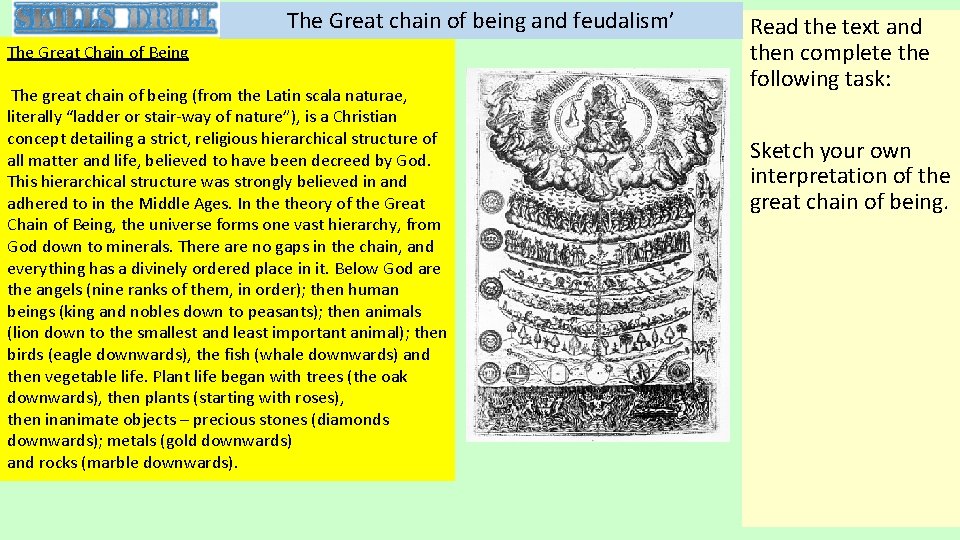

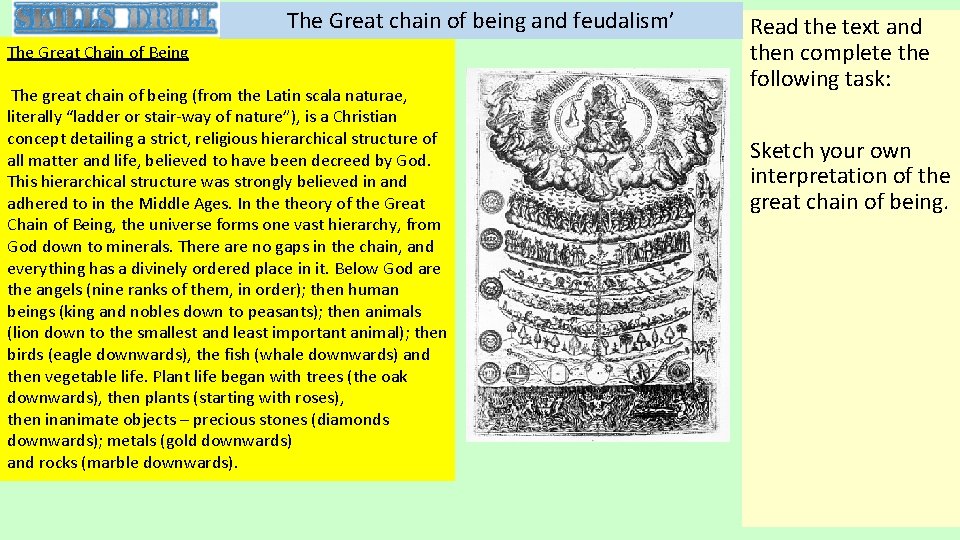

The Great chain of being and feudalism’ The Great Chain of Being The great chain of being (from the Latin scala naturae, literally “ladder or stair-way of nature”), is a Christian concept detailing a strict, religious hierarchical structure of all matter and life, believed to have been decreed by God. This hierarchical structure was strongly believed in and adhered to in the Middle Ages. In theory of the Great Chain of Being, the universe forms one vast hierarchy, from God down to minerals. There are no gaps in the chain, and everything has a divinely ordered place in it. Below God are the angels (nine ranks of them, in order); then human beings (king and nobles down to peasants); then animals (lion down to the smallest and least important animal); then birds (eagle downwards), the fish (whale downwards) and then vegetable life. Plant life began with trees (the oak downwards), then plants (starting with roses), then inanimate objects – precious stones (diamonds downwards); metals (gold downwards) and rocks (marble downwards). Read the text and then complete the following task: Sketch your own interpretation of the great chain of being.

The Great chain of being and feudalism’ Feudalism To some extent, the feudal society that operated in the Middle Ages linked in to the concept of the Great Chain of Being. Feudal means to do with land held on condition of service. A related word is fealty, which is loyalty to the person superior to you who owns the land you work on. For example, a peasant working on the land belonging to the lord of the manor owed loyalty to that lord of the manor. The economy was based on agriculture, so land was extremely important. Society was held together by loyalty / fealty between individuals. Dukes, marquises, earls and barons owed loyalty to the king (and peers still give an oath of allegiance to the monarch in the coronation ceremony). Less important knights owed loyalty to their superiors. Yeoman farmers were loyal to the knights. Peasants owed loyalty to the farmers, or to a knight. The idea was that your superior would protect you and grant you the right to hold and work the land, and in return you would serve as a soldier in his army. This is how the king raised an army when he needed to. Gradually, with the rise of the middle classes, some of whom we meet in the Canterbury Tales, merchants and industrialists built up wealth not based on the possession of land, and professional soldiers took over the role of the armoured knights on the battlefield. Profit became more important than loyalty. In Chaucer’s day only the first signs of this gradual change can be seen. Read the text and then answer the following questions: 1. What does ‘feudal’ mean? 2. What does ‘fealty’ mean? 3. Who did peasants owe loyalty to? 4. What eventually began to be considered more important than loyalty? Stretch: Explain the concept of feudalism in less than 30 words.

The Miller How would you describe this character? Make sure to: • Write in full sentences • Produce at least four sentences • Include at least five impressive adjectives Stretch: Produce a monologue from the perspective of the character giving an indication of his personality.

Read the description of the Miller as a class. Copy and complete the chart with quotations from the text. Face Build Physical strength Clothing and equipment Personal qualities Write a detailed description of the miller in your own words.

The Miller’s Tale As is fitting in a society dominated by the powerful aristocracy, the knight, who is the most aristocratic of the pilgrims, told the first tale, a long, slow-moving courtly romance about two young knights in love with a beautiful and noble lady. The Host, organising the story-telling which whiles away the time on the four-day journey to Canterbury, calls upon the monk to tell the next tale. In doing this he is observing the strict social order, because the monk, being a man of rank in the church, is the next most aristocratic of the pilgrims. However, before the monk can even open his mouth, the miller bellows his way unceremoniously into the midst of the conversation. He is so drunk on ale that he is pale and can hardly stay on his horse. Regardless of the manners due to his social superiors, he begins shouting and swearing, claiming that he knows a noble tale to tell that will match the knight’s tale.

John, a carpenter who lives in Oxford, is married to a young, pretty woman named Alison. They have a lodger in their house, who is a clerk or student of the University of Oxford, named Nicholas and Alison take a shine to each other, and Nicholas hatches a plan so he can spend the night with Alison away from her husband. Nicholas is studying astrology among other things, and tells John that he has worked out that a second Flood – bigger than the one from the time of Noah in the Bible – is coming, and that John, being a carpenter, should make preparations to save them from the imminent deluge. John sets about building three tubs which can be suspended from the roof of the outhouse, saving the three of them from the waters. While John is asleep in his tub, Alison and Nicholas sneak off to be alone together. At this point, however, Absolon – who is, like Nicholas, a clerk, and who, like Nicholas, fancies Alison – comes by the house and stops at the window, wanting to seduce Alison. When he refuses to leave her alone, she offers to kiss him through the open window, and promptly sticks her naked backside out the window, so Absolon kisses it. He is disgusted and runs to borrow a red-hot iron from the nearby blacksmith.

Absolon then returns with the red-hot iron, and this time Nicholas sticks his backside out of the window – and farts in Absolon’s face. Absolon shoves the red-hot iron in Nicholas’ bum, prompting Nicholas, in pain, to cry out for water. Waking at the sound of the shouting, John, still in his tub, hears Nicholas shouting ‘water’ and thinks the Flood is coming. He severs the ropes that are holding the tubs to the roof and falls down, breaking his arm. John’s neighbours all think he’s gone mad.

• • • How could the Miller’s interruption be seen as contradicting the great chain of being? Are there any morals or messages contained in The Miller’s tale? Stretch: What comments do you think the tale makes about the ‘educated’?

• What knowledge have you learnt today? • What skills have you learnt/developed today? • How has your previous learning helped you today?