Legal Update OACP 2020 Annual Conference MATT LOVE

- Slides: 44

Legal Update: OACP 2020 Annual Conference MATT LOVE OMAG DEPUTY GENERAL COUNSEL

Kansas v. Glover 589 U. S. _, 140 S. Ct. 1183 (2020) Officer did not unlawfully stop a driver for suspicion of driving under a revoked license where the Officer ran a vehicle’s registration, discovered it had 1 registered owner whose license the Officer knew had been revoked by the State. “The fact that the registered owner of a vehicle is not always the driver of the vehicle does not negate the reasonableness of Deputy Mehrer’s inference. ” Justice Sotomayor (dissenting): only common sense inferences which are derived from law enforcement training may be used. Majority’s response: “Such a standard defies the ‘common sense’ understanding of common sense, i. e. , information that is accessible to people generally, not just some specialized subset of society. ” While LE training and experience can play a significant roll in evaluating reasonable suspicion, “such experience is not required in every instance. ”

Supreme Court Watch Torres v. Madrid: Court will decide whether a 4 th Amendment seizure occurs when officers shoot a suspect while attempting to seize them but the suspect gets away. 8 th, 9 th and 11 th Circuits (with the New Mexico Supreme Court) hold that it does, while the D. C. and 10 th Circuit have held that it does not. See Torres v. Madrid, 769 Fed. Appx. 654 (10 th Cir. 2019). Qualified Immunity (Q. I. ): Court turned away numerous Q. I. cases last term. 3 Justices had expressed a desire to modify or do away with Q. I. (Thomas, Sotomayor and Ginsburg). Judge Amy Coney Barrett (7 th Cir. ) is the leading contender to replace Justice Ginsburg. She has authored or voted with the majority to deny qualify immunity in at least 7 cases in her 2 years on the 7 th Circuit. Howard v. Koeller, 756 Fed. Appx. 601 (7 th Cir. 2018), Wallace v. Baldwin, 895 F. 3 d 481 (7 th Cir. 2018), Miller v. Larson, 756 Fed. Appx. 606 (7 th Cir. 2018), Walker v. Price, 900 F. 3 d 933 (7 th Cir. 2018), Brooking v. Branham, 727 Fed. Appx. 884 (7 th Cir. 2018), Broadfield v. Mc. Grath, 768 Fed. Appx. 544 (7 th Cir. 2019) & Rainsberger v. Benner, 913 F. 3 d 640 (7 th Cir. 2019).

Est. of Smart v. City of Wichita 951 F. 3 d 1161 (10 th Cir. 2020) Judges resolve legal disputes, juries resolve factual disputes. 4 th Amendment violated when Officers shot an active shooter where there was a fact dispute about whether he posed a threat in the moment he was shot. Officers granted Q. I. on the initial shots at the fleeing suspect. Officers not required to give a warning in this situation. Q. I. denied to officers for shots fired after the suspect had fallen, arms outstretched, with no gun or weapon in his hands. Whether the officer had time to evaluate whether the suspect still posed a threat was a question for the jury.

Myers v. Brewer 773 Fed. Appx. 3 d 1032 (10 th Cir. 2019) (unpublished) Officers respond to a call about a man with a shotgun in front of a bar 41 minutes after it was received. Undersheriff yells “Put your hands up!” while a Deputy yells “Get on the ground!” 8 seconds later, they shoot the suspect with a beanbag. Q. I. denied. Possession of the shotgun outside the bar was not unlawful. Suspect was clearly unarmed when Officers encountered him. Suspect complied with all commands except for the “inconsistent commands” about putting his hands up or getting on the ground.

Mc. Cowan v. Morales 945 F. 3 d 1276 (10 th Cir. 2019) Officer denied Q. I. when he was accused of failing to seatbelt a prisoner during transport and then intentionally drove in a reckless manner causing injuries to the suspect. Court found this to be a gratuitous use of force against a fully compliant and subdued misdemeanant arrestee who posed no threat to anyone. Officer also denied Q. I. on a deliberate indifference to obvious medical needs claim. Suspect told the Officer about a preexisting shoulder injury, then repeatedly told the officer at the station that he was in excruciating shoulder pain after the car ride. Officer ignored the complaints for 2 hours.

Est. of Valverde v. Dodge 967 F. 3 d 1049 (10 th Cir. 2020) Officers engaged in a reverse-buy-bust of 40 kilos of cocaine from a known drug and arms dealer. When SWAT moved in, suspect was ordered to raise his hands, which he failed to do. Instead he began grabbing for something in his waistband area. Valverde pulled a gun from his waistband and, within a second, Ofc. Dodge fired 5 rounds, striking him 3 times. Family argued he was pulling the gun to put it on the ground and surrender. Officer appealed denial of Q. I. “[T]he district court failed to consider that allowance needs to be made for the fact that the officer must make a split-second decision. The Constitution permits officers to make reasonable mistakes. Officers cannot be mind readers and must resolve ambiguities immediately. … Perhaps a suspect is just pulling out a weapon to discard it rather than to fire it. But waiting to find out what the suspect planned to do with the weapon could be suicidal. ” Video evidence crucial: “Viewing the video, no jury could doubt that Dodge made his decision to fire before he could have realized that Valverde was surrendering. ”

Est. of Valverde v. Dodge 967 F. 3 d 1049 (10 th Cir. 2020) Timing critical: “It is also clear from the video that Valverde did not extend his right arm away from his body (apparently to drop the weapon) until about half a second before the first shot was fired and he did not begin to raise his hands toward his head until about a quarter-second before Dodge fired. The law permitted Dodge to fire as soon as he saw the gun in Valverde’s hand. This is not a case where the officer had sufficient time to appreciate that the suspect was no longer a danger before the officer decided to fire. ” An Officer is not required to “await the glint of steel before taking self-protective action; by then, it is often too late to take safety precautions. ” Quoting Est. of Larsen v. Murr, 511 F. 3 d 1255 (10 th Cir. 2008). Officer does not violate the 4 th Amendment if he reasonably feared that he and the public were in danger, even though the suspect may have ceased being a deadly threat in the “sanitized world of [a Judge’s] imagination. ”

Reavis v. Frost 967 F. 3 d 978 (10 th Cir. 2020) Suspect attempts to run Officer over. Over jumps out of the way, draws and opens fire as the suspect is passing him. Q. I. denied to the Officer. 2 nd Factor from Graham (threat to Officer or others) is the most important in a deadly force case. Review is from the perspective of an objectively reasonable officer evaluating whether the threat existed “in the precise moment that [the Officer] used deadly force”. Deadly force may be used in response to an imminent threat from a vehicle, but not based on the “general dangers posed by reckless driving. ” At the moment the Officer opened fire, he was out of harms way. A jury must decide if the Officer had enough time to reasonably perceive and respond to the change in circumstances. Driver was the suspect in an ADW, but the Officer did not argue that he had PC to believe this or that this would support PC to believe the driver was a threat to others.

Emmett v. Armstrong _ F. 3 d _ (10 th Cir. 9/1/2020) Officers are not required to verbally identify themselves before arresting a person for noncompliance. Question is whether it was objectively reasonable for an officer to believe the suspect knew he was an officer before requiring compliance. Here, a uniformed officer arrived in a marked unit running code 3, began detaining suspects in a brawl outside a bar, and then gave Emmett commands which led to the flight. But: “It continues to be the best practice, of course, for officers to identify themselves as such when practicable. ” Q. I. denied on the excessive force claim. After officer chased Emmett down and tackled him, the Officer stood over Emmett who was laying on his back laughing but making no movements. Officer ordered him to roll over, which Emmett did not do. Officer then yelled “You’re going to get TASE’d” and immediately deployed the Taser. Suspect was being arrested for a minor crime, was not a threat, was passively resisting, and the Officer did not give Emmett time to comply with the warning before using the TASER.

Mglej v. Gardner _ F. 3 d _ (10 th Cir. 9/9/2020) Off-duty Deputy received a call from a local convenience store that $20 was missing from the register. Suspect description matched Mglej, a person the Deputy had stopped for speeding 2 days prior. Deputy went to the house Mglej was staying at to confront him. Mglej denied involvement in theft, but the off-duty Deputy advised he needed Mglej’s ID and identifying information for a report. Mglej declined to provide the information without speaking to an attorney, so the Deputy arrested him. Held: no Probable Cause for the arrest. Obstruction statute not applicable (Judge had not ordered Mglej to provide info). Stop & ID statute not applicable because 1) not in a “public place”, 2) only requires the suspect to provide a name (he did) and 3) Officer argued it started as a consensual encounter. To the extent the Deputy even arguably had PC to arrest for theft (he did not) that PC fully dissipated when the store called the Deputy while he was in route to the jail with Mglej and advised that the $20 had been located and was not missing.

Mglej v. Gardner _ F. 3 d _ (10 th Cir. 9/9/2020) Deputy not liable for excessive force merely because he handcuffed Mglej. Excessive force evaluated separate from false arrest and presumes PC existed. Deputy could be held liable for cuffing Mglej too tightly so as to cause and injury (here, nerve damage) because he ignored Mglej’s complaints about the cuffs being too tight for 15 -30 minutes before then checking and determining that they were too tight and causing injury. Deputy drove home to change into his uniform and then had Mglej come into his garage where he used personally owned tools to try to pry the cuffs off since they malfunctioned. Deputy could be held liable for malicious prosecution. The malice element could be inferred by the fact that the Deputy lacked even arguably probable cause. Court further noted that, when they arrived at the Jail, the Deputy was asked what the charge was and responded “I don’t know. Let me look at the book. I am sure I can find something. ”

Coddington v. Sharp 959 F. 3 d 947 (10 th Cir. 2020) No 5 th Amendment violation when Officers gave Miranda to a suspect and then transported the suspect to the station where the interview was resumed 3 hours later without giving Miranda again. Suspect was asked at the start of the second interview if he remembered receiving Miranda and still wanted to talk to the Officers, to which he said yes. Waiver of Miranda rights must be knowing and voluntary. Suspect need not be told each possible subject of questioning for the waiver to be effective. Suspect’s intoxication does not automatically invalidate the waiver unless the intoxication rises to the level of substantial impairment or indicates that the suspect’s will was overborne by all the circumstances surrounding the confession.

U. S. v. Latorre 893 F. 3 d 744 (10 th Cir. 2018) Three types of citizen-Police encounters: consensual, detainment and arrest. Officer’s consensual encounter inadvertently became a detention when the pilot of a craft suspected to be carrying drugs voluntarily handed the Officer his pilot’s license and registration and the Officer did not give it back. Luckily, the Court found (through vertical collective knowledge) that reasonable suspicion existed which would justify a detention.

U. S. v. Gaines 918 F. 3 d 793 (10 th Cir. 2019) Seizure can occur through: a show of police authority or through use of physical force. A show of authority does not result in a seizure unless the person submits to the Officer’s authority. When Officers pulled up to a suspect with red/blue lights on, this constituted a show of authority notwithstanding the Officers’ intention to initiate a consensual encounter. Since Officers lacked reasonable suspicion at this point, the detention was unlawful. The drugs that were discovered as a result of the encounter were inadmissible. Fact that the suspect ran from the Officers after a brief exchange did not change the fact that he submitted to their authority initially. At that point he was seized, and his subsequent flight did not affect the initial seizure.

U. S. v. Mayville U. S. v. Morales 955 F. 3 d 825 (10 th Cir. 2020) 961 F. 3 d 1086 (10 th Cir. 2020) Rodriguez v. U. S. , 575 U. S. 348 (2015): 4 th Amendment violated with Officers prolong a traffic stop beyond the time reasonably needed to complete the tasks incident to the stop’s mission (traffic enforcement) absent reasonable suspicion of other criminal activity. An officer’s mission during a traffic stop is both “to address the traffic violation that warranted the stop and attend to related safety concerns. … Traffic stops are especially fraught with danger to police officers” such that “negligibly burdensome” inquiries an officer needs to make “to complete his mission safely” among permissible actions incident to a traffic stop. “[T]he government’s officer safety interest stems from the mission of the stop itself. ” Running a Triple-I through dispatch rather than checking criminal history on an in-car computer (Mayville) or a 15 minute call to a national law enforcement database to check criminal history (Morales) did not unreasonably prolong these two traffic stops.

Kapinski v. City of Albuquerque 964 F. 3 d 900 (10 th Cir. 2020) Murder suspect claimed his 4 th Amendment rights were violated under Franks v. Delaware, 438 U. S. 154 (1978) when Officer failed to include information about a surveillance video that the suspect claimed supported his claim that he fired in self defense. Franks claim requires 1) a showing that the Officer omitted material information from their PC Affidavit and 2) that the omission was intentional or reckless. Omitted information is only “material” if, had it been included, PC would have dissipated. While a jury could view the video and believe the shooting was in self defense, it was not conclusive and, had it been included, PC would have still existed. Officer was not reckless in omitting the information. Officer included information in the Affidavit from witnesses which would support self defense.

Kapinski v. City of Albuquerque 964 F. 3 d 900 (10 th Cir. 2020) “Perhaps Detective Juarez’s affidavit would have been more complete had she, out of an abundance of caution, included the video footage in her affidavit. But not every failure to perform police investigations in a perfectly thorough manner renders them constitutionally infirm. ” Lying in an Affidavit is clearly unconstitutional for Q. I. purposes. There remains “significant ambiguity” for Q. I. purposes when reckless omissions are at issue. It is not clearly established that a Franks violation occurs when an Officer fails to include ambiguous evidence in a PC Affidavit where one interpretation of that evidence may cast doubt on a suspect’s guilt.

Corona v. Aguilar 959 F. 3 d 1278 (10 th Cir. 2020) Officer violated the 4 th Amendment when he arrested a passenger in a car under the State’s Stop & ID statute. On a routine traffic stop, a passenger is seized without any reasonable suspicion or probable cause to believe the passenger has committed a crime. Such a seizure is still reasonable for 4 th Amendment purposes. Officer can 1) order the passenger to stay in the vehicle, 2) order the passenger to exit the vehicle but stay on the scene, and 3) ask the passenger for identification. None of these actions violates the 4 th Amendment. Officer cannot arrest a person for failing to identify themselves if there was no individualized reasonable suspicion as to that person. See Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial Dist. Ct. , 542 U. S. 177 (2004) and Brown v. Texas 443 U. S. 47 (1979). Q. I. denied. OK is not a Stop & ID State. You can always ask, but an arrest goes too far.

Donahue v. Wihongi 948 F. 3 d 1177 (10 th Cir. 2020) Officers did not falsely arrest Donahue under State’s Stop & ID statute. Statute only applies if Officer has reasonable suspicion to detain the suspect. Officer had reasonable suspicion to believe Donahue was publicly intoxicated. Officer was responding to a disturbance and the RP, who had personal contact with Donahue, advised he was “drunker than Cooter Brown. ” When talking to Donahue, he admitted he had a verbal alteration with the RP and that he had been drinking. Donahue’s claims that he was “articulate” and “wasn’t slurring his words” did not dissipate reasonable suspicion. Reasonable suspicion “may exist even if it is more likely than not that the individual is not involved” in a crime and it “need not rule out the possibility of innocent conduct. ” Donahue should have known he was being detained and violated the Stop & ID statute when he failed to provide his name.

U. S. v. Shrum 908 F. 3 d 1219 (10 th Cir. 2018) Seizure occurs when there is some meaningful interference with a possessory interest in property. Illinois v. Mc. Arthur, 531 U. S. 326 (2001): If PC to believe home contains evidence of a serious crime that might otherwise be destroyed, you can lawfully secure the home and restrict entry while waiting a search warrant. Officers “seized” suspect’s home during death investigation despite never entering the home when officers deprived suspect his ability to access his home for his own purposes, in his own way, on his own time, and at a location where concerned friends could visit. No P. C. here: This was a “fishing expedition to see what sort and how big of fish the police might catch. … We have news for the Government. No such thing as a ‘crime scene exception, ’ let alone an ‘unexplained death scene exception, ’ to the Fourth Amendment exists. ”

U. S. v. Loera 923 F. 3 d 907 (10 th Cir. 2019) When executing a search warrant for a particular piece of evidence, Officers can only search places where the evidence might conceivably be located. U. S. v. Ross, 456 U. S. 798 (1982). How does this limitation work with searching for the “needle-in-a-haystack” of searching a computer hard drive when you stumble across evidence of an unrelated crime? 10 th Circuit adopted a 4 part test to determine if Officers acted unlawfully in searching files unrelated to the subject of their warrant: (1) length of time the searching officer reviewed the incriminating, nonresponsive evidence; (2) whether the nonresponsive files were set apart from the responsive files; (3) the manner in which the evidence was discovered (purposefully versus inadvertently); and (4) the breadth of the search method employed

U. S. v. Neugin 958 F. 3 d 924 (10 th Cir. 2020) Officers responded to a verbal domestic at a restaurant parking lot. The couple’s truck had broken down. As the wife began gathering her belongings, one Officer lifted the lid of a “camper” attached to the back of the truck in an effort to “help” the wife gather belongings and observed ammunition, which the husband claimed was his. Dispatch then reported that the husband was a convicted felon and officers arrested him for unlawful possession of ammunition AFC. The Officer’s lifting of the lid violated the 4 th Amendment because it intruded into an area where the husband had a legitimate expectation of privacy. No Law Enforcement basis to do this – i. e. no probable cause. Community Caretaker roll did not justify the action. Officer was not asked to help, the wife could have done it herself, and it was not done to protect anyone.

Law Enforcement Impact of Mc. Girt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452 (2020)

Holding Murphy v. Royal, 875 F. 3 d 896 (10 th Cir. 2017) affirmed Sharp v. Murphy, 140 S. Ct. 2412 (2020) Mc. Girt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452 (2020) Patrick Murphy was convicted and sentenced to death for Murder in the 1 st Degree. Jimcy Mc. Girt was convicted of various sex crimes and sentenced to 1, 000 plus life for molesting, forcibly sodomizing and raping his wife’s 4 year old granddaughter. Held: Under Solem v. Bartlett, 465 U. S. 463 (1984) that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation had never legally been disestablished and continues to exist to this day. Because both Murphy and Mc. Girt were Indian, their victims were Indian, and their offenses occurred within the Creek reservation, the State had no jurisdiction to prosecute them.

Holding Murphy v. Royal, 875 F. 3 d 896 (10 th Cir. 2017) affirmed Sharp v. Murphy, 140 S. Ct. 2412 (2020) Mc. Girt v. Oklahoma, 140 S. Ct. 2452 (2020) Both cases were limited to the question of the Creek reservation existence. The issues as to the Creek reservation are nearly identical to the likely existence of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw and Seminole reservations. But those reservations have not yet been formally recognized as having not been disestablished. Only a matter of time? Oklahoma Federal Courts and the 10 th Circuit will be bound to follow Murphy and Mc. Girt. Justice Ginsburg was in the narrow, 5 -4, majority in Mc. Girt. While it is possible her replacement might swing the majority to the State in a future case involving 1 of the 4 other Tribes, it is unlikely unless the State raises a new argument for disestablishment.

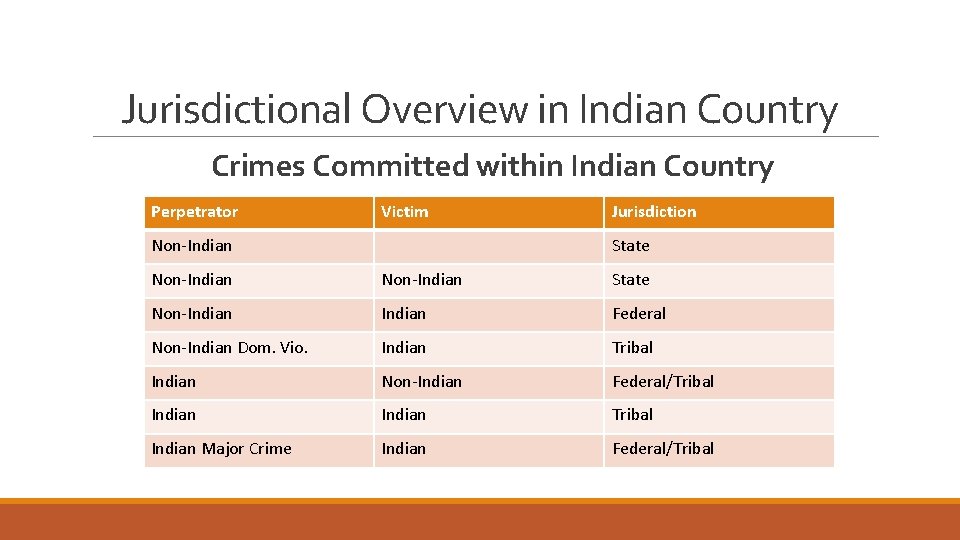

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Crimes Act / General Crimes Act (18 U. S. C. § 1152): enacted in the 1790’s, amended in 1854. Federal Law governs in Indian Country except for crimes committed by an Indian against an Indian victim, or perpetrators who have already been punished in Tribal Court, or where a Treaty grants jurisdiction to the Tribe. “Indian Country” not defined until 1948. 18 U. S. C. § 1151 now defines Indian Country as including 1) reservations, 2) dependent Indian communities or 3) land which is held in trust or subject to legal restrictions on alienation. Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U. S. 556 (1883): Federal Government has no criminal jurisdiction over a crime involving an Indian perpetrator and Indian victim. 1885: Sen. Henry Dawes introduced the Major Crimes Act in response to Crow Dog. Yes, that “Dawes”

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Major Crimes Act (18 U. S. C. § 1153): extended Federal criminal jurisdiction over 7 major crimes where the victim and perpetrator were both Indian. That list of crimes has been expanded to include: murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, maiming, a felony under 18 U. S. C. Chap. 109 (sex abuse), incest, a felony assault under 18 U. S. C. § 113, an assault against an individual who has not attained the age of 16 years, felony child abuse or neglect, arson, burglary, robbery, and a felony under 18 U. S. C. § 661 (theft of property over $1, 000). Tribes retained jurisdiction over crimes committed by Indians, but in Duro v. Reina, 495 U. S. 676 (1990) the Court ruled that this jurisdiction was limited to Tribal members. 1991 “Duro Fix” (25 U. S. C. § 1301): Tribes have criminal jurisdiction over all Indians.

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country U. S. v. Mc. Bratney, 104 U. S. 621 (1881): Tribes have no criminal jurisdiction over non-Indian on non-Indian crimes. Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U. S. 191 (1978): Tribes have no inherent criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians. 2013 Violence Against Women Act: extended Tribal criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians who commit domestic violence crimes against Indian victims.

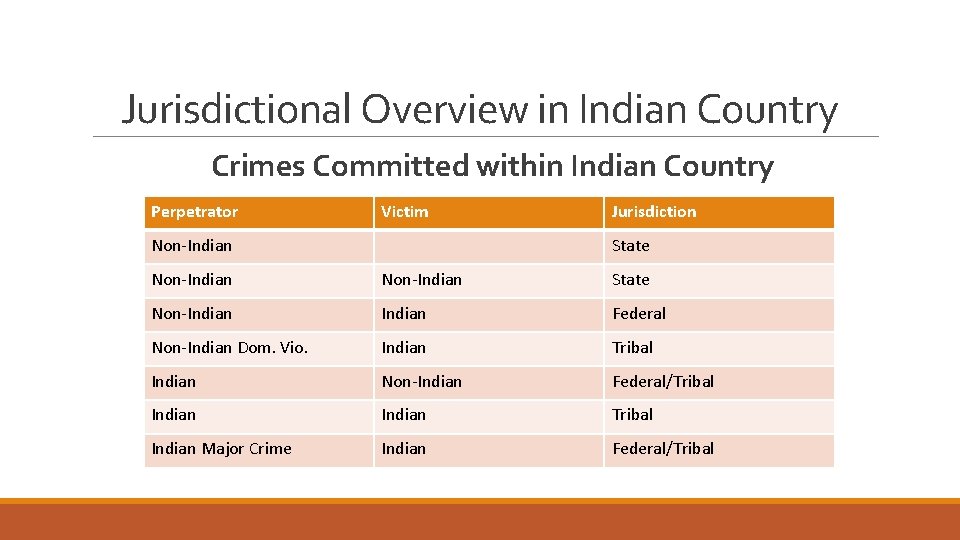

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Crimes Committed within Indian Country Perpetrator Victim Non-Indian Jurisdiction State Non-Indian Federal Non-Indian Dom. Vio. Indian Tribal Indian Non-Indian Federal/Tribal Indian Major Crime Indian Federal/Tribal

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Who is an “Indian” – Not defined by Federal statutes. U. S. v. Rogers, 45 U. S. 567 (1845): The term “Indian” in the Federal statutes “does not speak of members of a tribe, but of the race generally - of the family of Indians; and it intended to leave them both, as regarded their own tribe, and other tribes also, to be governed by Indian usages and customs. ” 2 prong test: does the person (1) have some Indian blood; and (2) is the person recognized as an Indian by a Federally recognized Tribe; Scrivner v. Tansy, 68 F. 3 d 1234 (10 th Cir. 1995).

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Recognition can be shown by considering: 1. Tribal enrollment; 2. Government recognition formally and informally through receipt of assistance reserved only to Indians; 3. Enjoyment of the benefits of tribal affiliation; and 4. Social recognition as an Indian through residence on a reservation and participation in Indian social life. Must be from one of the 574 Federally recognized tribes.

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Indian Blood U. S. v. Prentiss, 273 F. 3 d 1277 (10 th Cir. 2001): proof of membership in a Tribe “does not itself establish that either of them had any Indian blood. ” U. S. v. Zepeda, 792 F. 3 d 1103 (9 th Cir. 2015): the recognition prong requires a tie to a Federally recognized tribe, the blood requirement is not limited to tribes that still have Federal recognition. The Bureau of Indian Affairs will issue a Certificate degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) card which will evidence the degree of Indian blood a person has. Cases have held that up to 1/8 th Indian blood was sufficient. No definitive ruling that less than 1/8 th Indian blood would be insufficient.

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Practical considerations: Indian status and presence in Indian Country are not elements of a State crime, but they are Jurisdictional requirements for State cases. Many States shift the legal burden to the Defendant to raise their statute and location of the crime as being in Indian Country. At that point, a Court must consider the evidence to determine if the Court has jurisdiction. Jurisdiction is typically geographic – either the crime occurred within your jurisdiction or it did not. When a crime occurs in Indian Country, jurisdiction will also be individualized. Jurisdiction turns on the Indian status of either or both of the perpetrator and victim. What if either or both advise you that they are Indian?

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Practical considerations: Ability to arrest/cite turns on PC to believe State law was violated. PC does not require Officers to rule out the possibility that the person is innocent nor does it require proof by preponderance of the evidence that the activity violates State law. U. S. v. Winder, 557 F. 3 d 1129 (10 th Cir. 2009). Cannot ignore information that is available and relevant to PC. Information learned after PC exists but pre-arrest can dissipate probable cause. Hinkle v. Beckham Cty. Bd. Of Cty. Commissioners, 962 F. 3 d 1204 (10 th Cir. 2020). Post-arrest, the officer must release the person if probable cause has dissipated. Id. Bare proclamations or protests from the suspect are not enough. Id.

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Practical considerations: Production of a Tribal citizenship card technically does not establish Indian status because it does not establish the existence of some Indian blood. Claim of citizenship without documentation not enough. What about Tribal tags? Is the driver the sole registered owner or a permissive user? Multiple registered owners – one is clearly a member of a Tribe, but both? Tribal Police Dispatch may be contacted in an attempt to verify citizenship. If citizenship is confirmed, there would be a strong indication of Indian status. Probable cause is about what you know not what you don’t know.

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Practical considerations: PC is about probabilities, not certainties. Citizenship likely suggests a high probability of Indian blood, but there is no case on point. For jurisdictions located in 1 of the 4 Tribes possible reservations, there is an added complication in that those reservations have not yet been recognized as continuing to exist. Cross-Deputization: State and Municipal Officers can, by agreement with the Tribe, be cross deputized which extends the Tribes law enforcement jurisdiction to the Officers. This empowers the Officers to enforce Tribal codes when an Indian is accused of committing a crime within Indian Country. Each Agency must decide whether cross-deputization is desirable. Absent such an agreement, Officers will lack jurisdiction to enforce the law within their jurisdiction for particular citizens.

Jurisdictional Overview in Indian Country Practical considerations: Mc. Girt / Murphy do not automatically vacate prior convictions. Oklahoma’s Post-Conviction Procedure Act, 22 O. S. § 1080 et seq. allows a person convicted of a crime to seek to vacate the conviction based on an argument that the Court was without jurisdiction to impose the sentence in the first place. 22 O. S. § 1080(b). Subject Matter Jurisdiction: cannot be waived and can be raised at anytime. Post-Conviction relief becomes moot once a sentence has been satisfied. Fitchen v. State, 1992 OK CR 9, 826 P. 2 d 1000. Exception: Post-Conviction relief available after sentence has been satisfied if there is a possibility of a collateral legal consequence. Luna v. State, 1973 OK CR 389, 513 P. d 1399.

Municipal Jurisdiction in Indian Country The prior slides discuss jurisdiction as to State laws to Indians in Indian Country. Municipalities are political subdivisions of the State of Oklahoma and typically derive all power and authority from the State. If the State lacks jurisdiction, do Municipalities lack jurisdiction? Oklahoma was admitted to the Union in 1907. Numerous municipalities existed within the Indian Territory prior to 1907. Per Art. 18, § 2 of the Oklahoma Constitution: Every municipal corporation now existing within this State shall continue with all of its present rights and powers until otherwise provided by law, and shall always have the additional rights and powers conferred by the Constitution. What rights and powers did those municipalities possess pre-Statehood?

Municipal Jurisdiction in Indian Country Curtis Act of 1898 (§ 14) authorized the incorporation of Municipalities within the Indian Territory. To incorporate, a vote of the residents was required and that vote expressly had to be open to “All male inhabitants Qualified voters of such cities and towns over the age of twenty-one years, who are citizens of the United States or of either of said tribes, who have resided therein more than six months next before any election held under this Act, shall be qualified voters at such election. ” See Elk v. Wilkins, 112 U. S. 94 (1884) (Indians not citizens by birth). Once incorporated, the Curtis Act provided: all inhabitants of such cities and towns, without regard to race, shall be subject to all laws and ordinances of such city or town governments, and shall have equal rights, privileges, and protection therein.

Municipal Jurisdiction in Indian Country Cities and Towns formed prior to Statehood in 1907 were not political subdivisions of the State and did not derive their powers from the State. They were formed via the Curtis Act and their powers were those outlined in Arkansas law pursuant to an express grant of authority by the United States. Cities and Towns formed after Statehood are political subdivisions of the State and do derive their powers from the State of Oklahoma. Strong argument to make that those Cities and Towns also are subject to the grant of authority in the Curtis Act. See § 40 of the Oklahoma Enabling Act (providing that the laws applicable in Indian Territory in effect upon admission of Oklahoma into the Union remain in effect unless modified or repealed).

Municipal Jurisdiction in Indian Country § 14 of the Curtis Act has never been repealed and constitutes an express grant of authority to municipalities that the State of Oklahoma never received. Municipalities could enact and apply ordinances to all regardless of race. Uncertainty exists as to whether the Curtis Act authorizes municipalities today to enforce their ordinances against Indians. Argument #1: Morton v. Mancari, 417 U. S. 535 (1974) – “Indian” is not a racial classification. The reason the Court reached this conclusion was the fact that, during the mid-1900’s, Congress terminated the Federal recognition of certain Tribes. By 1974, not all people who had Indian blood could qualify as Indian due to the fact that they were not members of a Federally recognized Tribe. In 1898 when the Curtis Act was adopted, that was not the case.

Municipal Jurisdiction in Indian Country Argument #2: Muscogee (Creek) Nation v. Hodel, 851 F. 2 d 1439 (D. C. Cir. 1988): “we hold that the Curtis Act was repealed by the [Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act]”. Hodel not binding in Oklahoma. Hodel related to the question of whether the Creek Tribal Courts existed. BIA’s reliance on the Curtis Act and subsequent Acts abolishing the Courts failed due to the OIWA provisions allowing the Courts to the reconstituted. Cannons of construction in Indian law cases are liberal in favor of the tribes. Express repeal not required, but repeal by implication requires inconsistency in the laws. Municipal jurisdiction existed concurrently with Tribal jurisdiction under the Curtis Act. Tribal Courts would be disbanded in the future under the Act. Municipal jurisdiction was not contingent on abolition of Tribal Courts.

Municipal Jurisdiction in Indian Country Practical reality: Courts have never had to address the scope of § 14 of the Curtis Act or whether that Section continues to be effective. The issue is being raised in 2 Class Action lawsuits filed against 63 OMAG member cities and towns seeking recovery of all fines and costs paid in Municipal Courts by Indian Defendants. May take years for those challenges to be resolved and the Courts may resolve the case without ruling on the Curtis Act argument. Each City and Town must make an informed decision as to whether they will enforce local ordinances against Indian Defendants pursuant to the Curtis Act.

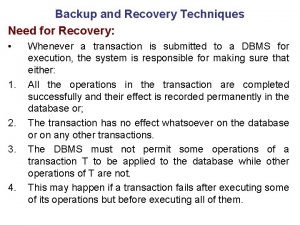

Afp annual conference 2020

Afp annual conference 2020 Alternative of log based recovery

Alternative of log based recovery Love love jesus is love god greatest gift lyrics

Love love jesus is love god greatest gift lyrics Organization development network annual conference

Organization development network annual conference Problemitize

Problemitize Hepi conference

Hepi conference Nmls resource center

Nmls resource center Gie annual conference

Gie annual conference Fuze conference 2018

Fuze conference 2018 Annual conference on pbfeam

Annual conference on pbfeam Travel health insurance association annual conference

Travel health insurance association annual conference Gcyf 2011 annual conference

Gcyf 2011 annual conference Njdv

Njdv Iowa league of cities annual conference

Iowa league of cities annual conference Edgar figueroa md mph

Edgar figueroa md mph Stfm annual conference

Stfm annual conference National trauma data bank annual report 2020

National trauma data bank annual report 2020 American psychiatric association annual meeting 2020

American psychiatric association annual meeting 2020 Revised annual teaching plans 2020

Revised annual teaching plans 2020 2021 revised curriculum and assessment plans

2021 revised curriculum and assessment plans Spring io conference 2020

Spring io conference 2020 Mip conference 2020

Mip conference 2020 Ansys innovation conference

Ansys innovation conference Alzheimers nz conference 2020

Alzheimers nz conference 2020 National conference for rabi campaign 2020

National conference for rabi campaign 2020 H2fc supergen conference 2020

H2fc supergen conference 2020 Imcat conference 2020

Imcat conference 2020 The salvation of man is through love and in love

The salvation of man is through love and in love That you must love me and love my dog summary

That you must love me and love my dog summary Passionate love vs companionate love

Passionate love vs companionate love Passionate love vs companionate love

Passionate love vs companionate love Infatuation meanin

Infatuation meanin What is a crush

What is a crush Infatuated

Infatuated Love is blind love is patient

Love is blind love is patient Consummate love vs companionate love

Consummate love vs companionate love Types of love

Types of love 5 love languages love tank

5 love languages love tank Love for the sake of love

Love for the sake of love Nothing can separate even if i ran away

Nothing can separate even if i ran away Oh my love my darling

Oh my love my darling Courtly love vs modern love

Courtly love vs modern love Richer than gold is the love of my lord

Richer than gold is the love of my lord Nominal character

Nominal character Love begets love

Love begets love