Lectures 25 26 Modeling and estimation energy methods

- Slides: 36

Lectures 25 & 26 Modeling and estimation energy methods – Rayleigh-Ritz flutter models i i Lagrange equations Generalized forces Rayleigh-Ritz approximations Virtual work Purdue Aeroelasticity 1

Objectives i Create models with few degrees of freedom but with reasonable accuracy i Set up aeroelastic problem with beamlike wing Purdue Aeroelasticity 2

Energy in Structural Systems i Structural systems store and transfer energy i Energy methods are an alternative to Newton’s Laws for developing equations of motion – no FBD’s are required i Structural systems store energy as kinetic energy and strain energy i Energy acquired equals work done on the system Purdue Aeroelasticity 3

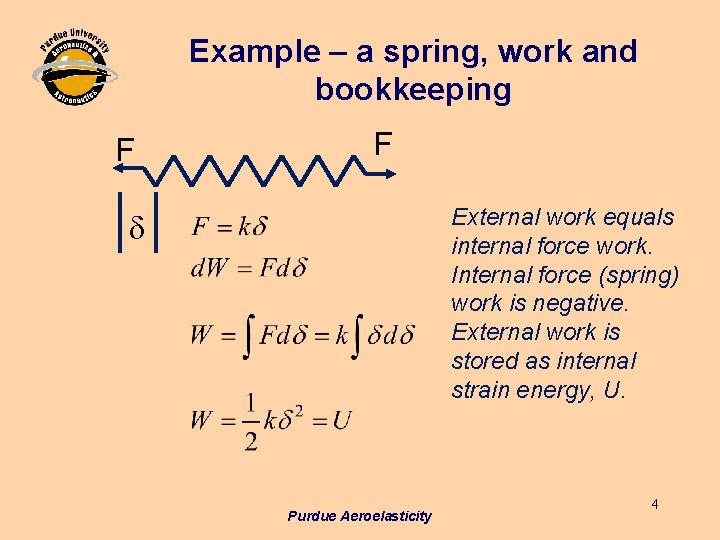

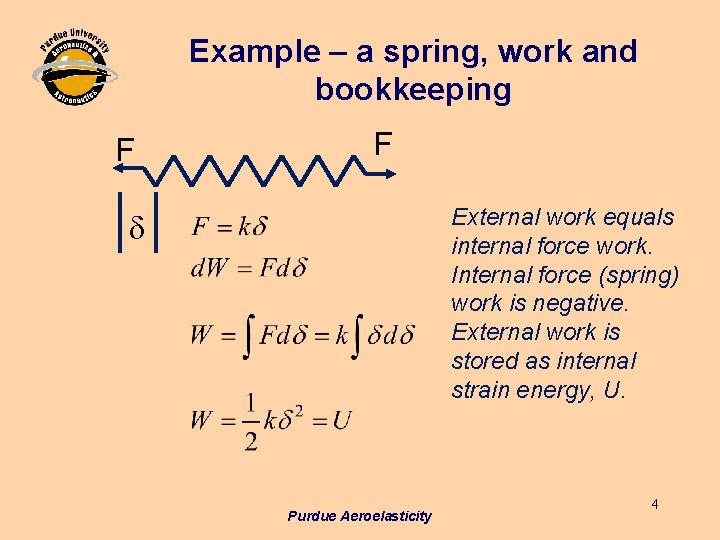

Example – a spring, work and bookkeeping F F External work equals internal force work. Internal force (spring) work is negative. External work is stored as internal strain energy, U. d Purdue Aeroelasticity 4

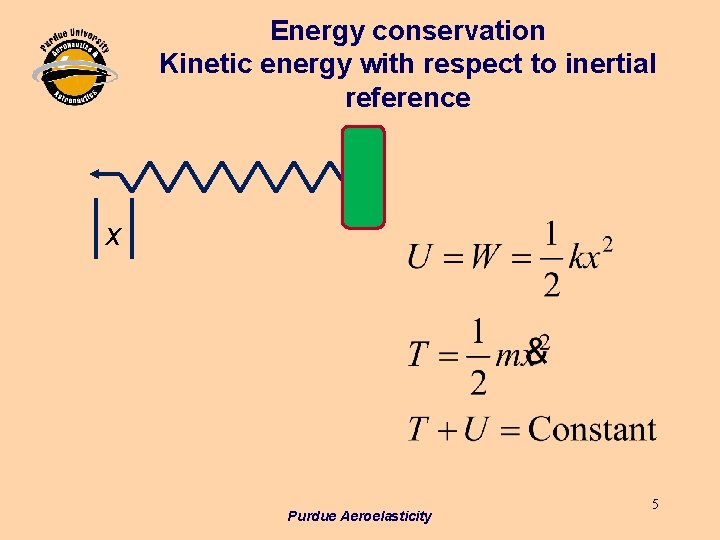

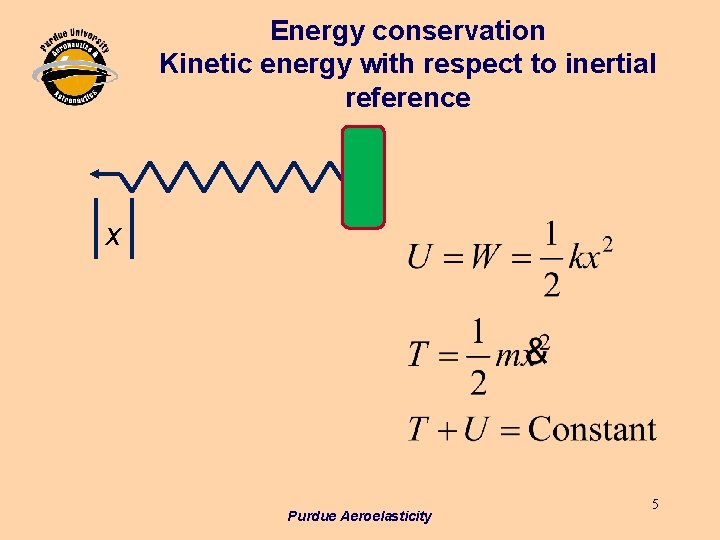

Energy conservation Kinetic energy with respect to inertial reference x Purdue Aeroelasticity 5

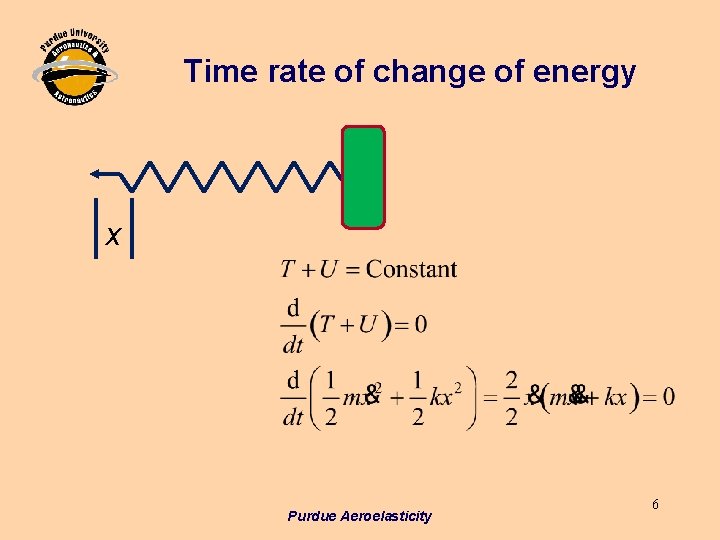

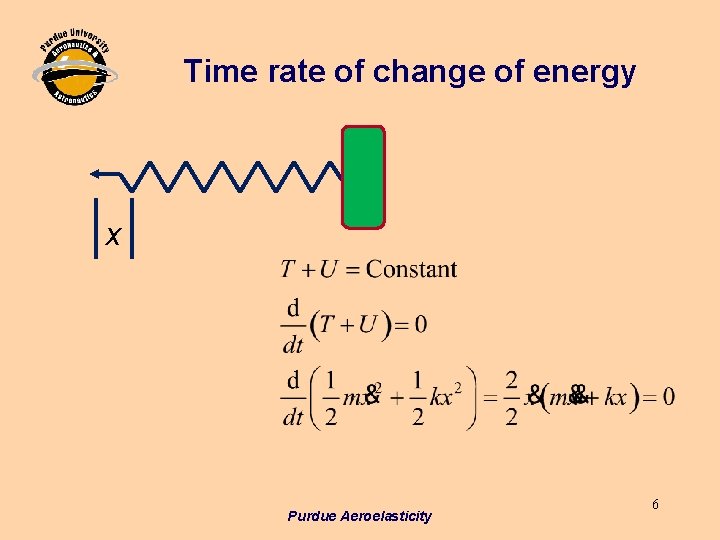

Time rate of change of energy x Purdue Aeroelasticity 6

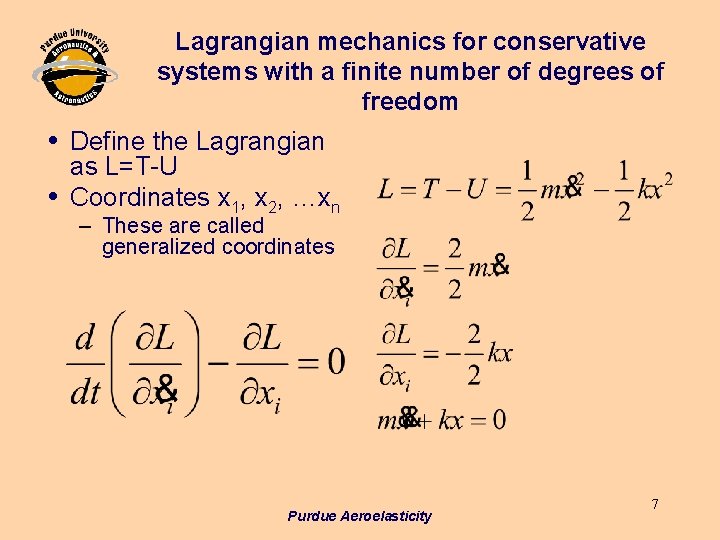

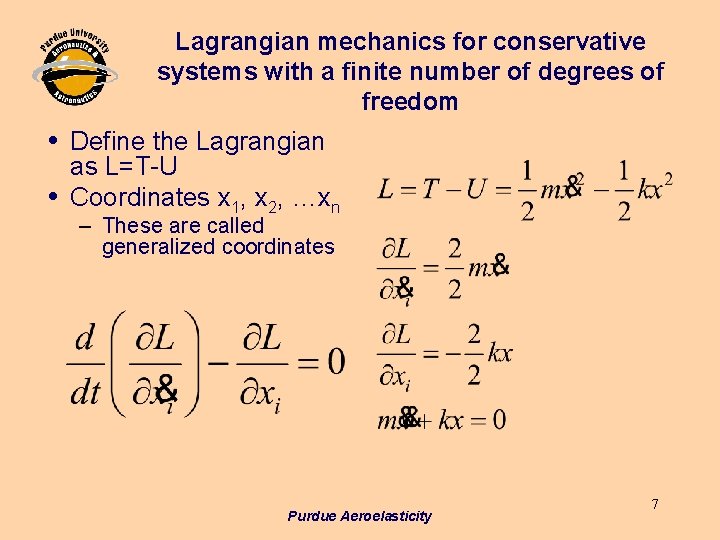

Lagrangian mechanics for conservative systems with a finite number of degrees of freedom Define the Lagrangian as L=T-U i Coordinates x 1, x 2, …xn i – These are called generalized coordinates Purdue Aeroelasticity 7

Continuous systems and the Rayleigh -Ritz method - a beam example i Compute kinetic energy and strain energy w(y, t) Purdue Aeroelasticity The internal forces are accounted for in the strain energy portion of L=T-U 8

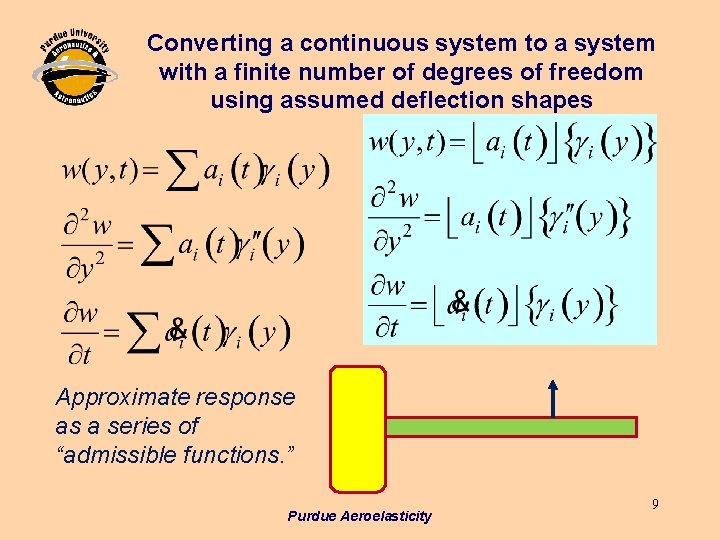

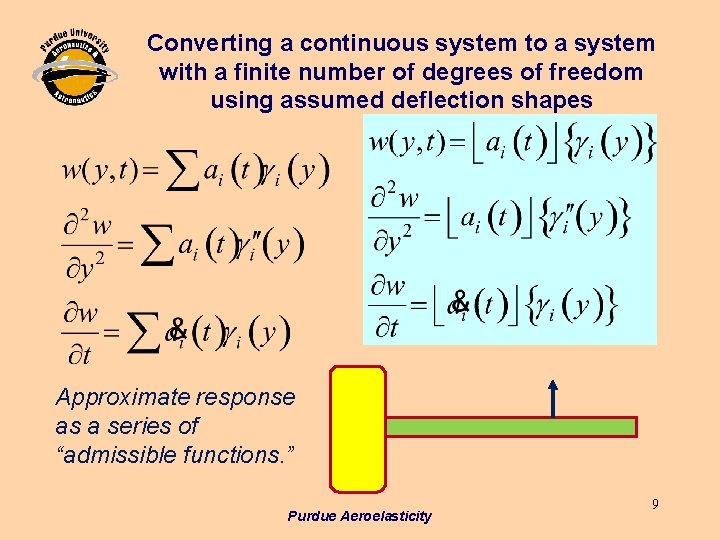

Converting a continuous system to a system with a finite number of degrees of freedom using assumed deflection shapes Approximate response as a series of “admissible functions. ” Purdue Aeroelasticity 9

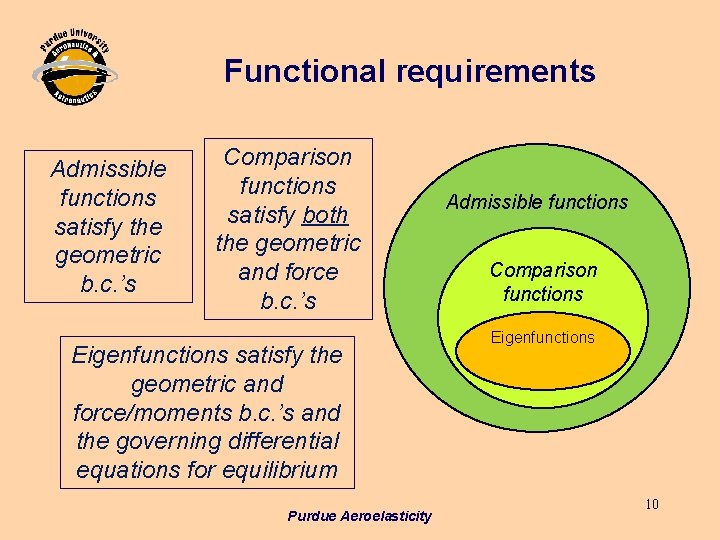

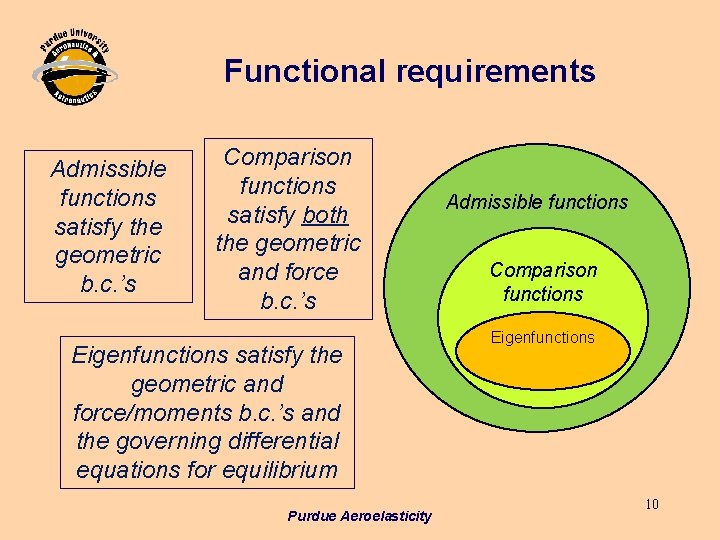

Functional requirements Admissible functions satisfy the geometric b. c. ’s Comparison functions satisfy both the geometric and force b. c. ’s Eigenfunctions satisfy the geometric and force/moments b. c. ’s and the governing differential equations for equilibrium Purdue Aeroelasticity Admissible functions Comparison functions Eigenfunctions 10

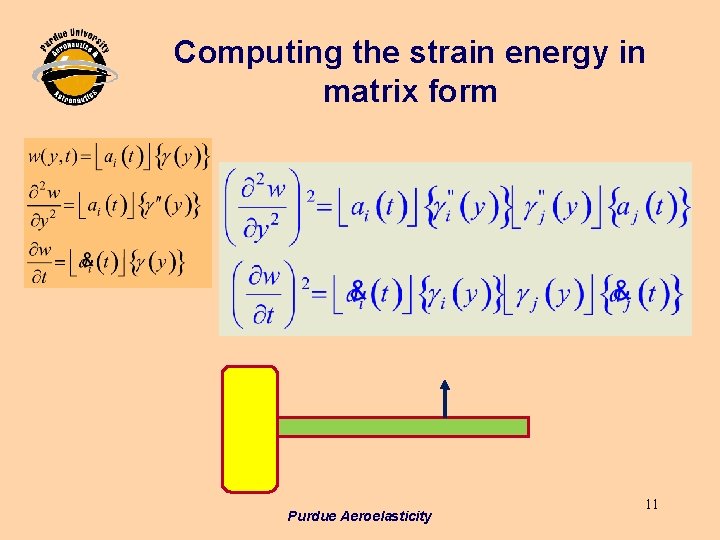

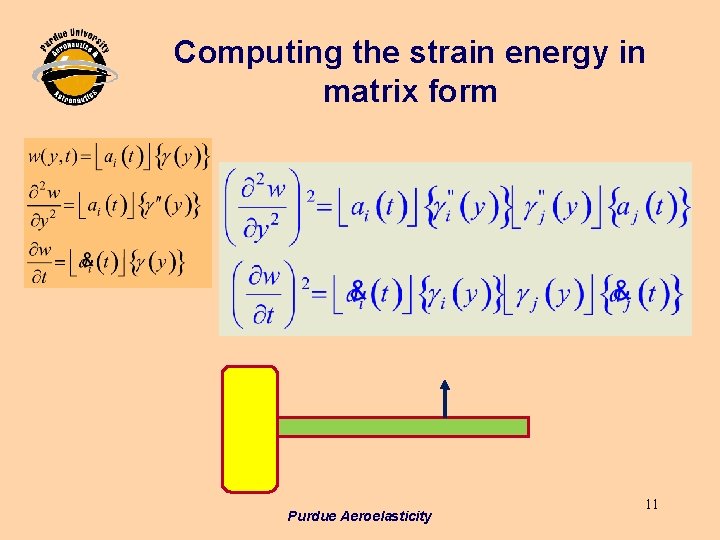

Computing the strain energy in matrix form Purdue Aeroelasticity 11

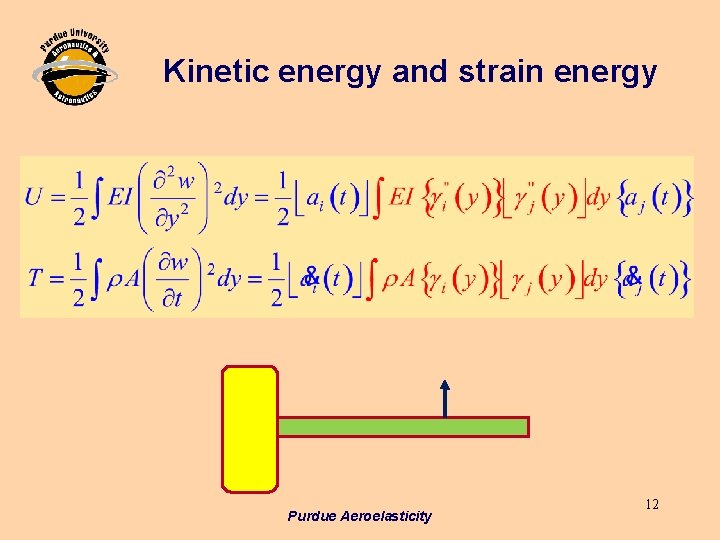

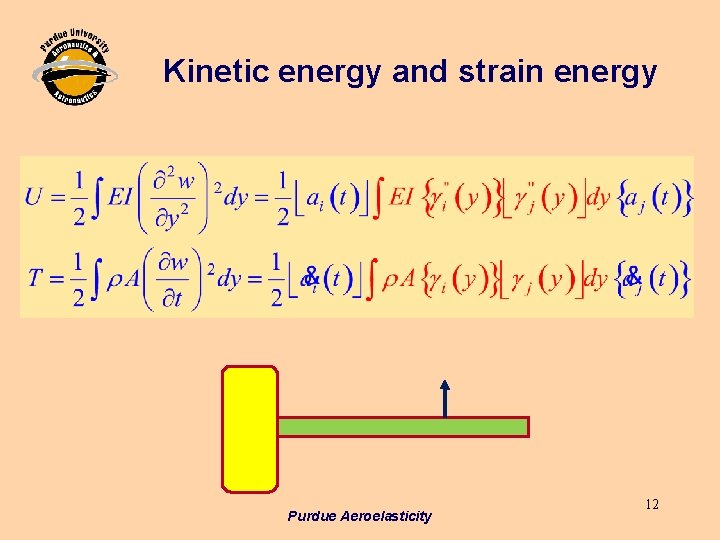

Kinetic energy and strain energy Purdue Aeroelasticity 12

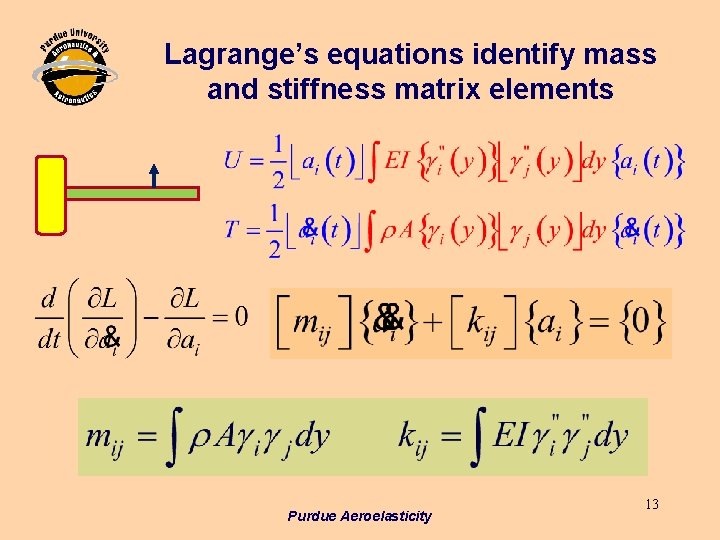

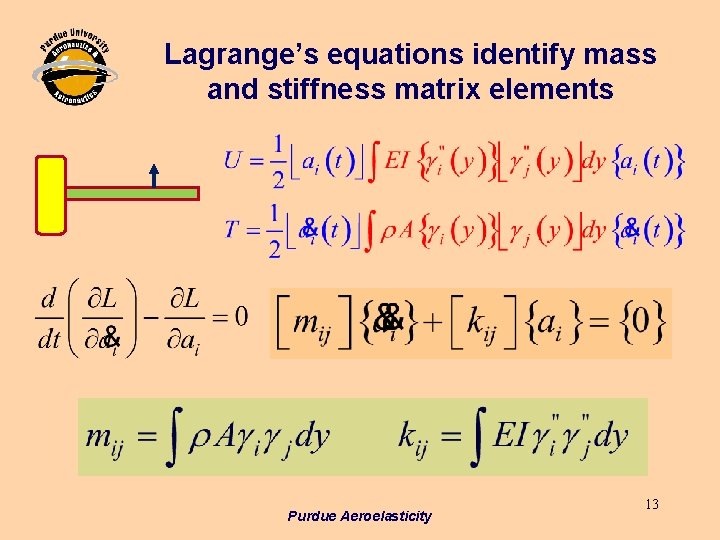

Lagrange’s equations identify mass and stiffness matrix elements Purdue Aeroelasticity 13

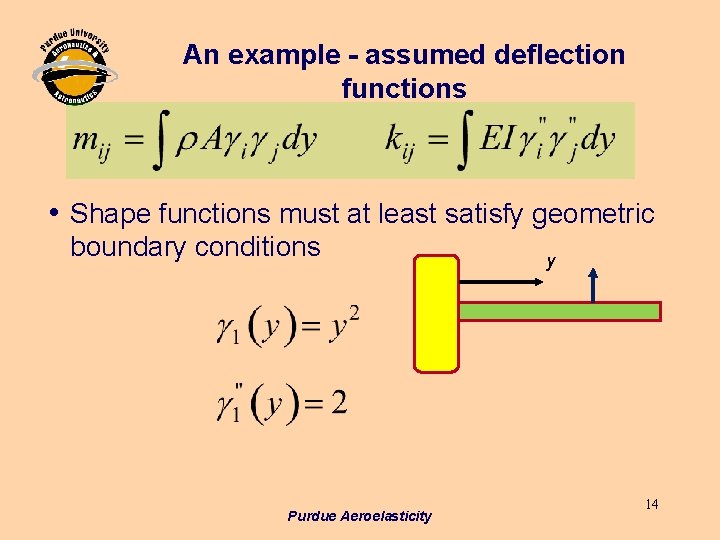

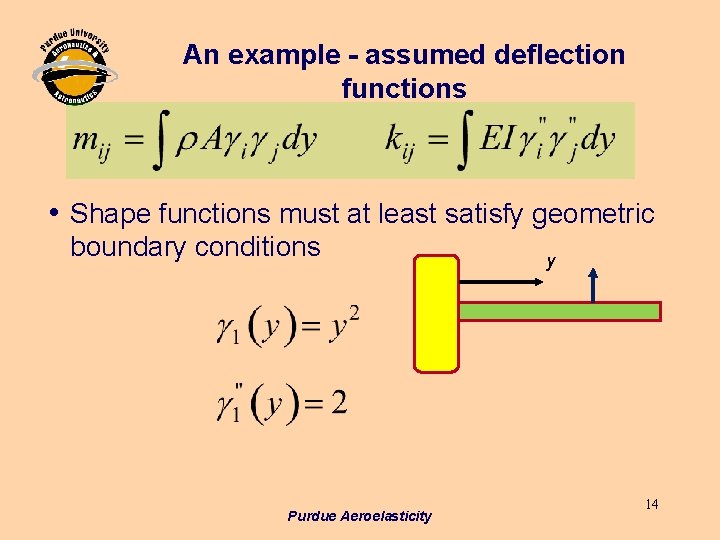

An example - assumed deflection functions i Shape functions must at least satisfy geometric boundary conditions y Purdue Aeroelasticity 14

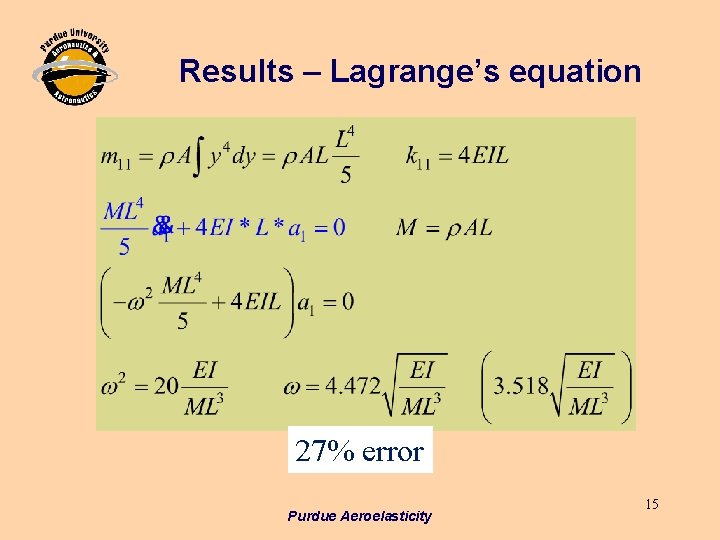

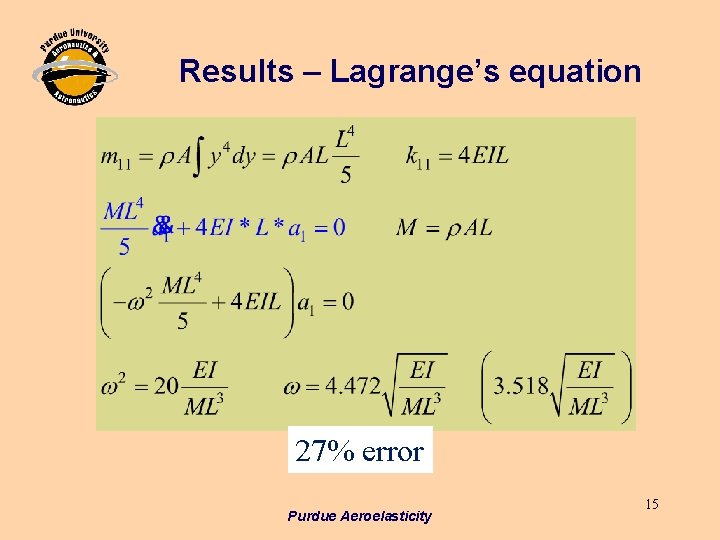

Results – Lagrange’s equation 27% error Purdue Aeroelasticity 15

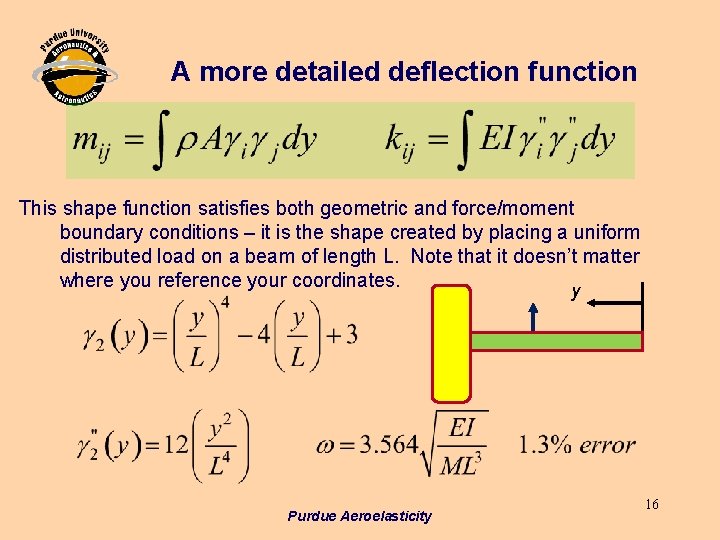

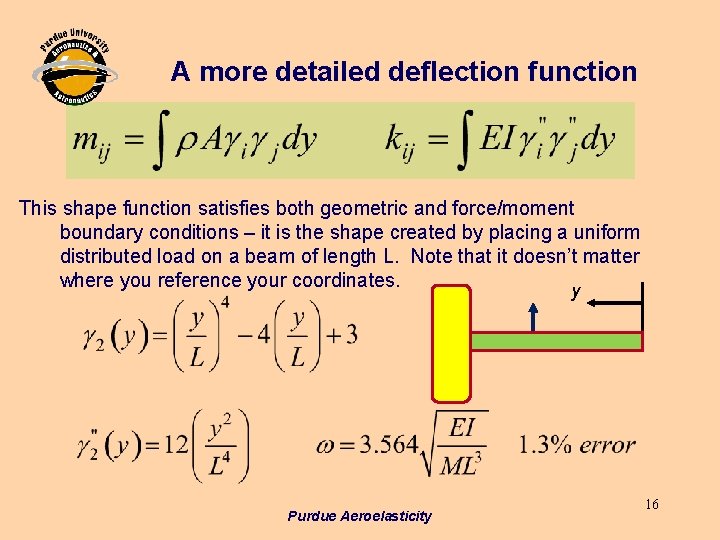

A more detailed deflection function This shape function satisfies both geometric and force/moment boundary conditions – it is the shape created by placing a uniform distributed load on a beam of length L. Note that it doesn’t matter where you reference your coordinates. y Purdue Aeroelasticity 16

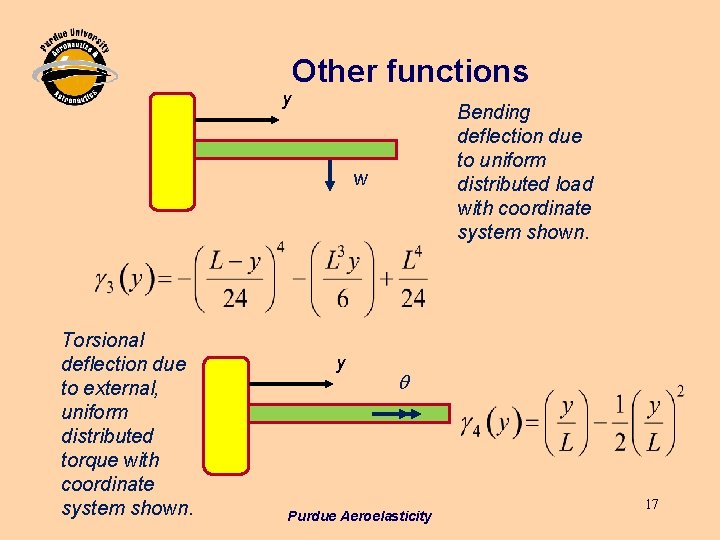

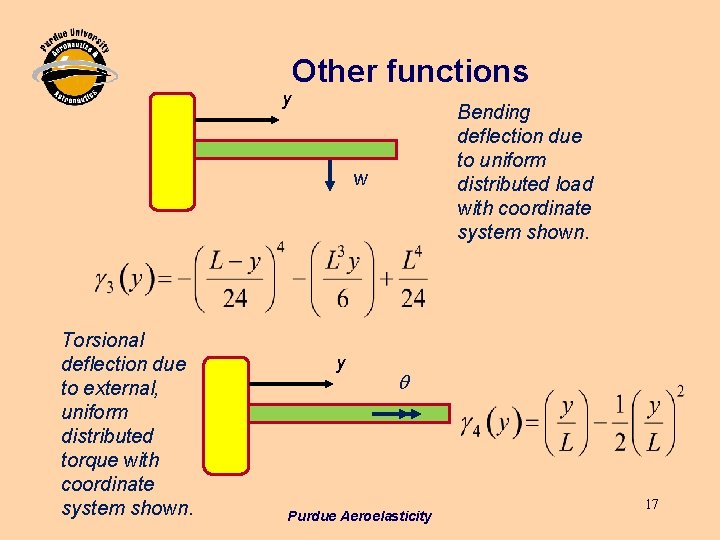

y Other functions Bending deflection due to uniform distributed load with coordinate system shown. w Torsional deflection due to external, uniform distributed torque with coordinate system shown. y q Purdue Aeroelasticity 17

First natural frequency and first three mode shapes Purdue Aeroelasticity 18

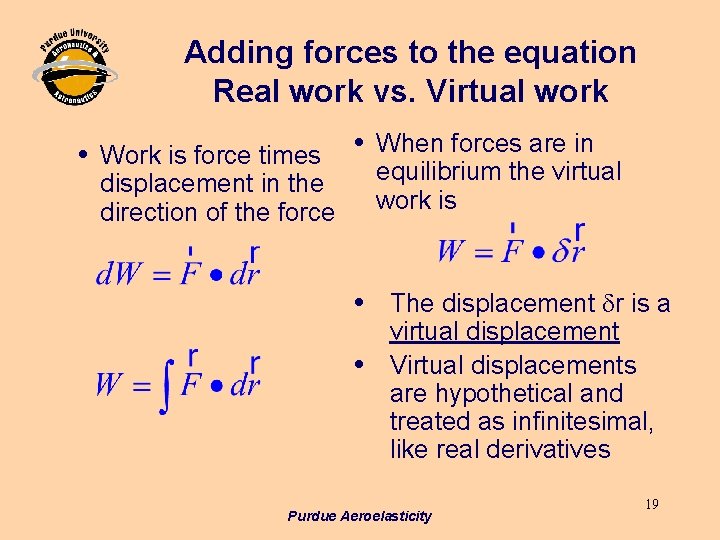

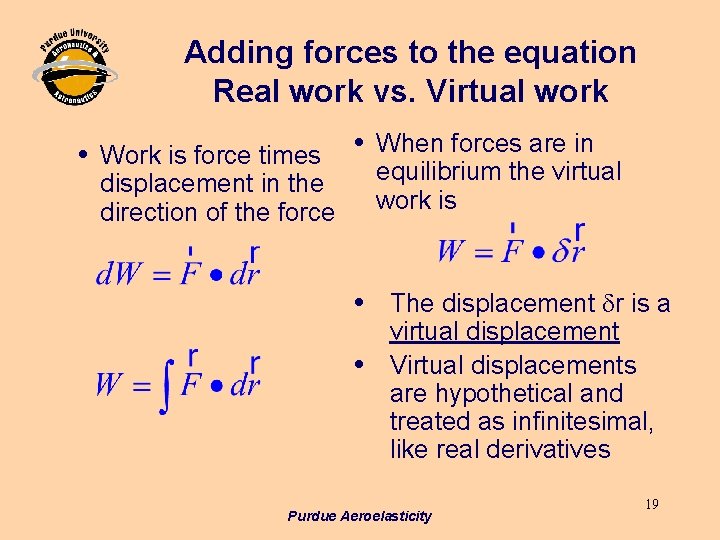

Adding forces to the equation Real work vs. Virtual work i Work is force times displacement in the direction of the force i i i When forces are in equilibrium the virtual work is The displacement dr is a virtual displacement Virtual displacements are hypothetical and treated as infinitesimal, like real derivatives Purdue Aeroelasticity 19

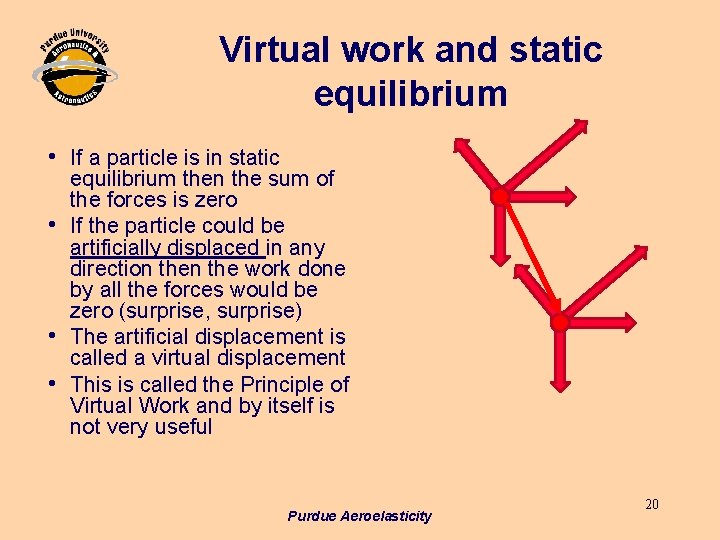

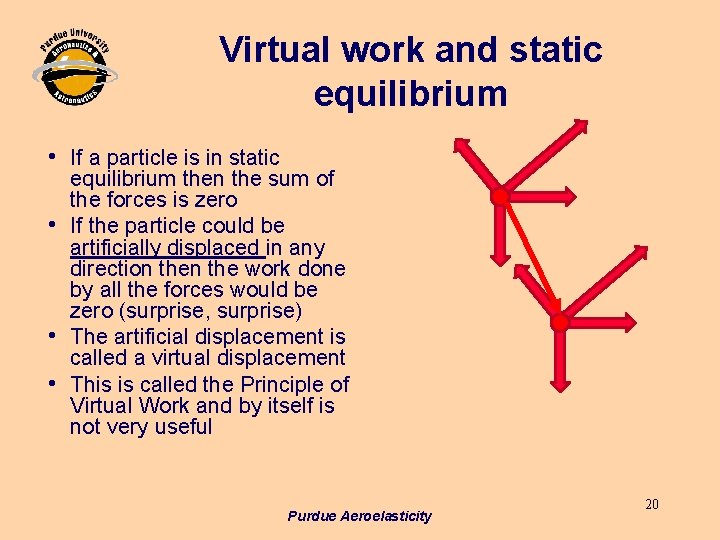

Virtual work and static equilibrium i i If a particle is in static equilibrium then the sum of the forces is zero If the particle could be artificially displaced in any direction the work done by all the forces would be zero (surprise, surprise) The artificial displacement is called a virtual displacement This is called the Principle of Virtual Work and by itself is not very useful Purdue Aeroelasticity 20

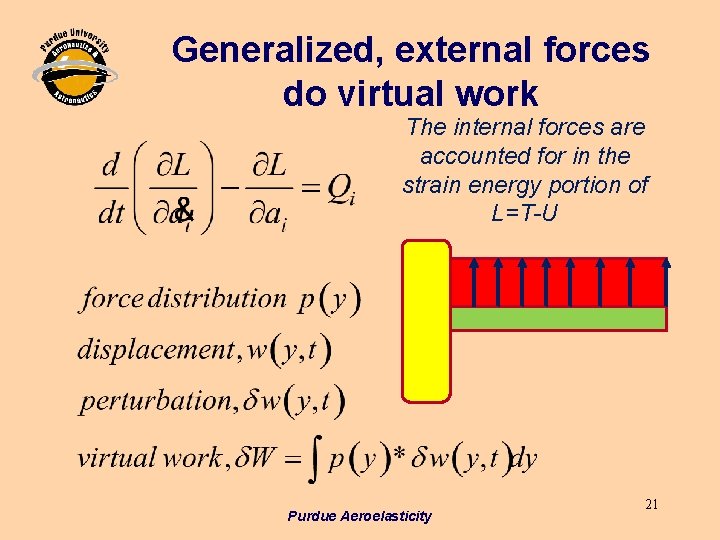

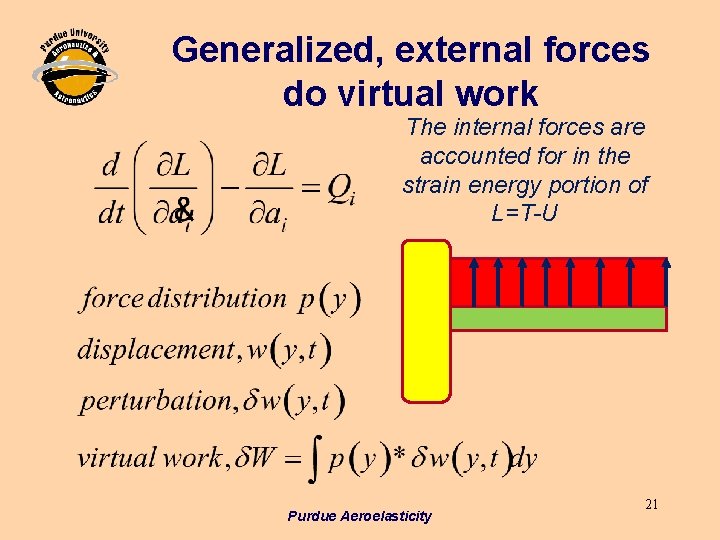

Generalized, external forces do virtual work The internal forces are accounted for in the strain energy portion of L=T-U Purdue Aeroelasticity 21

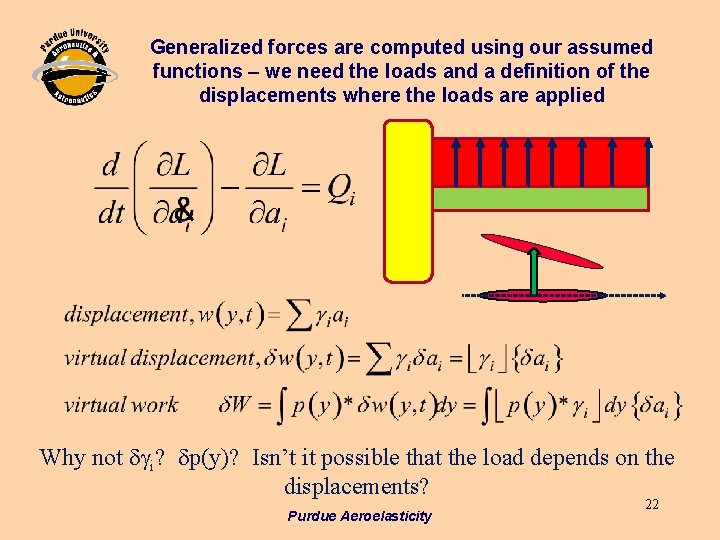

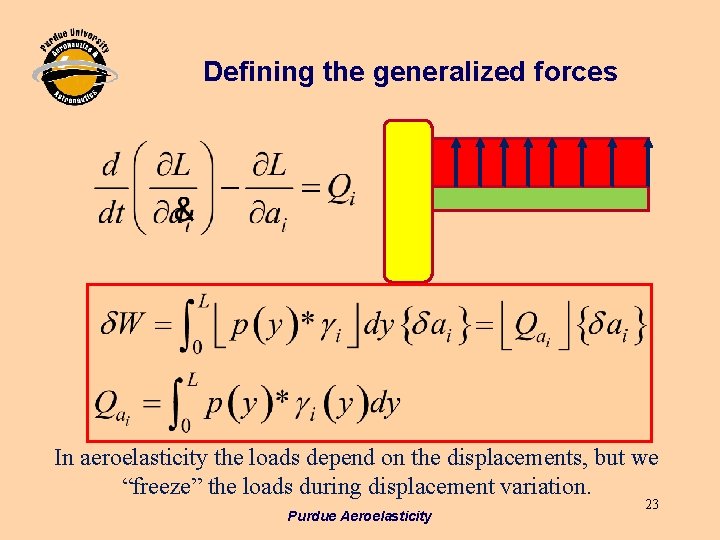

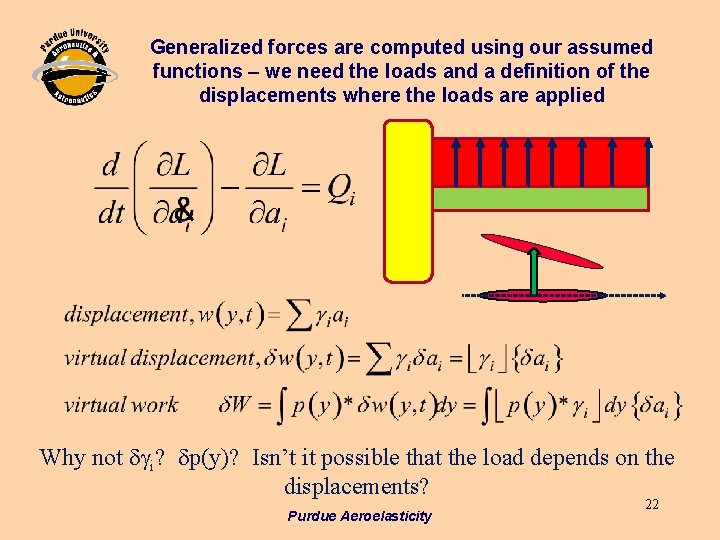

Generalized forces are computed using our assumed functions – we need the loads and a definition of the displacements where the loads are applied Why not dgi? dp(y)? Isn’t it possible that the load depends on the displacements? Purdue Aeroelasticity 22

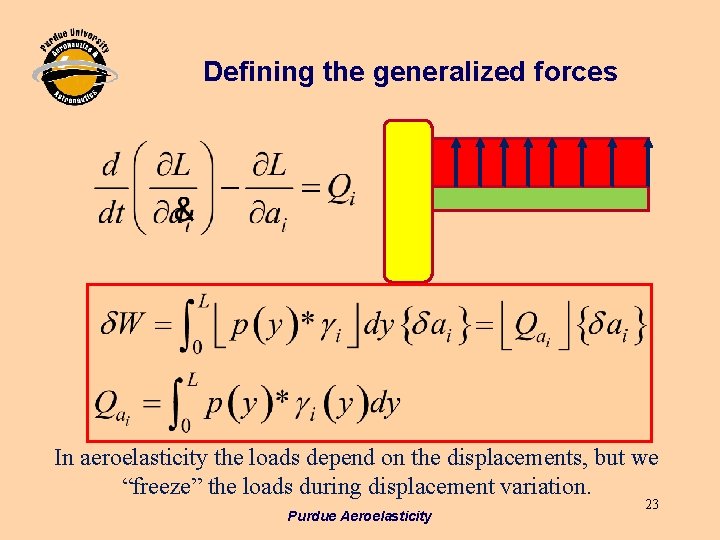

Defining the generalized forces In aeroelasticity the loads depend on the displacements, but we “freeze” the loads during displacement variation. Purdue Aeroelasticity 23

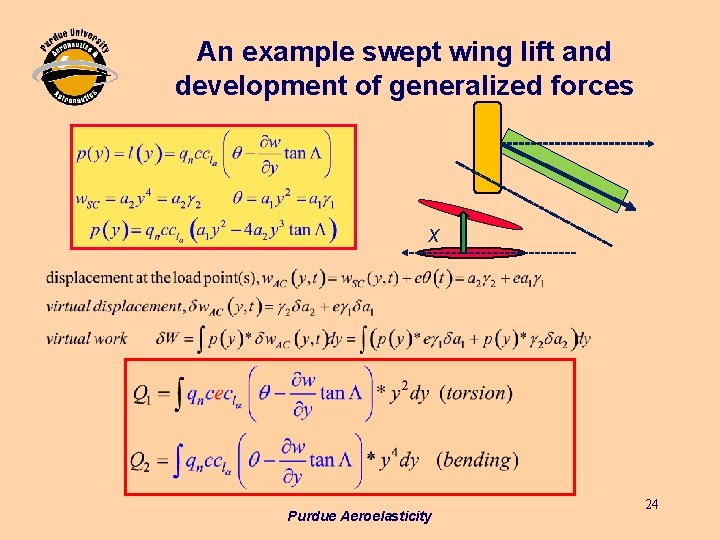

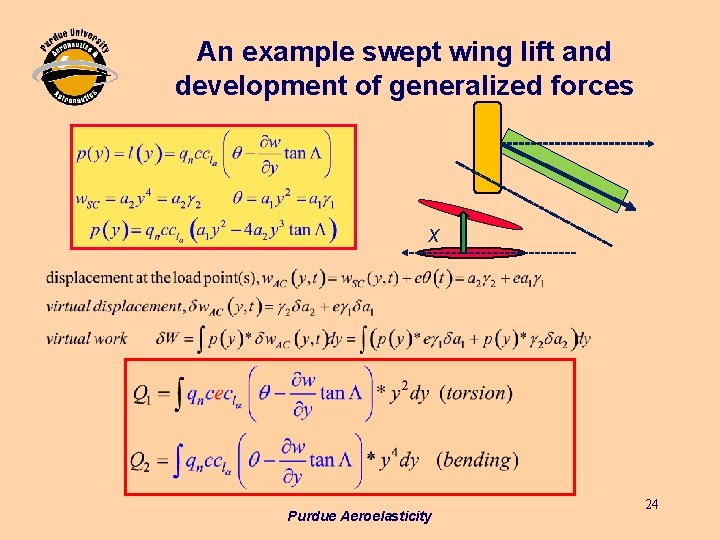

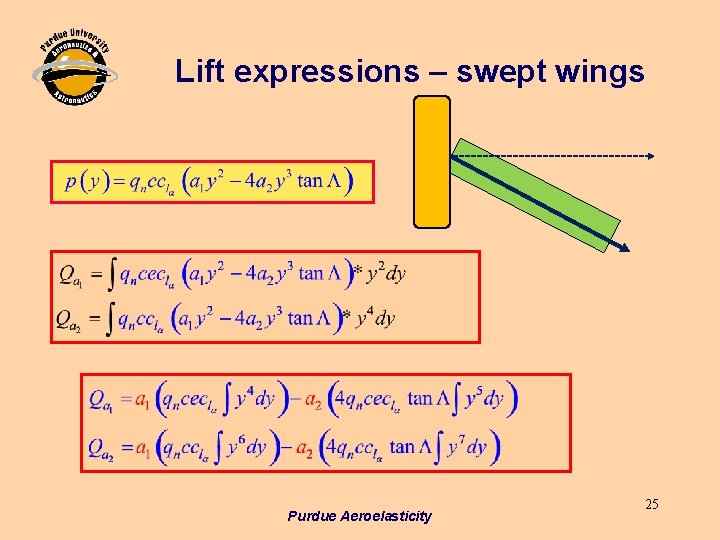

An example swept wing lift and development of generalized forces x Purdue Aeroelasticity 24

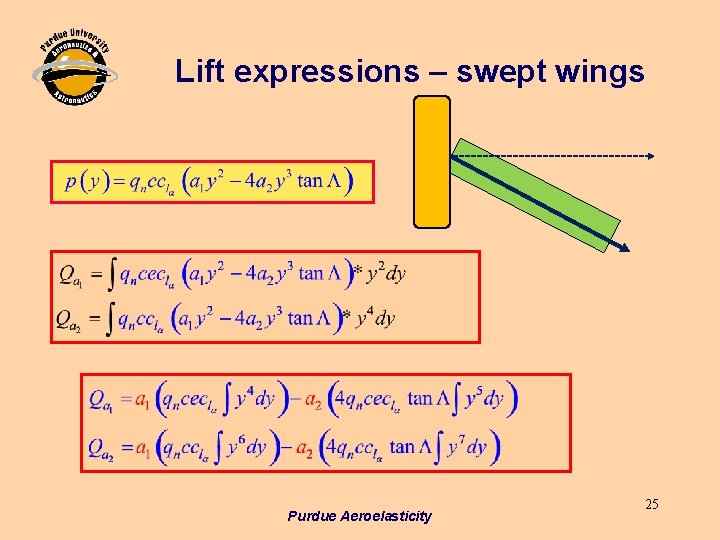

Lift expressions – swept wings Purdue Aeroelasticity 25

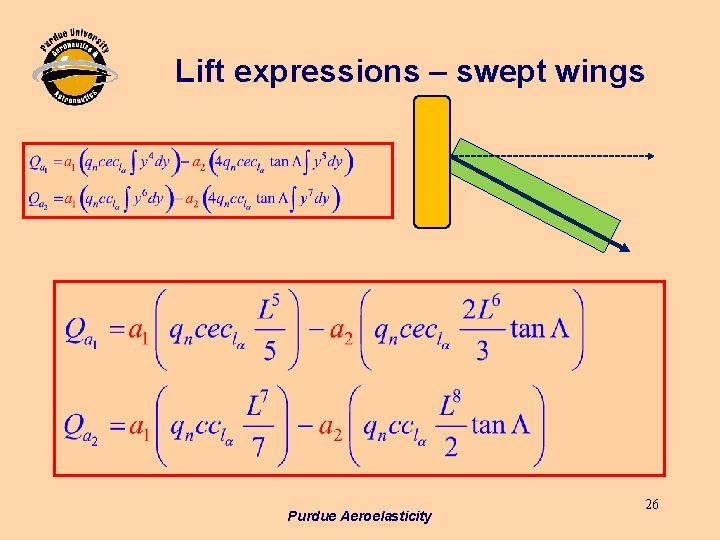

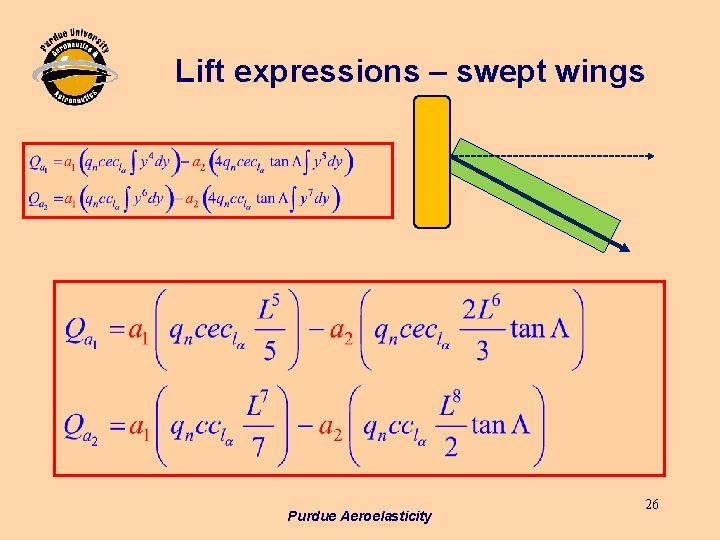

Lift expressions – swept wings Purdue Aeroelasticity 26

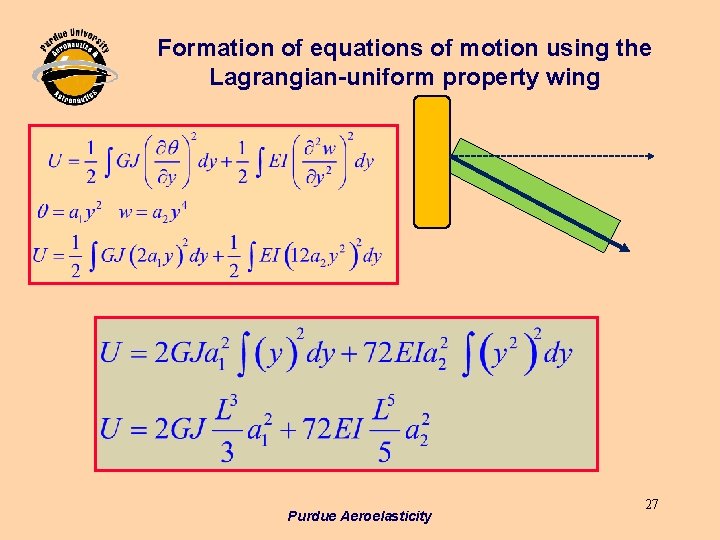

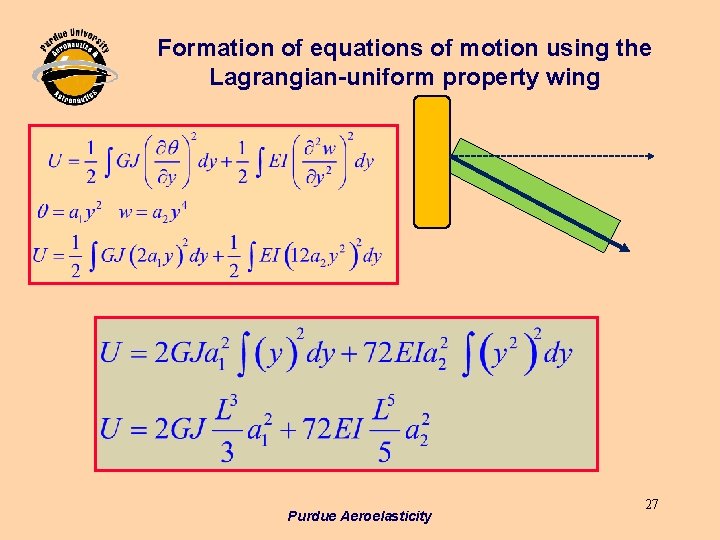

Formation of equations of motion using the Lagrangian-uniform property wing Purdue Aeroelasticity 27

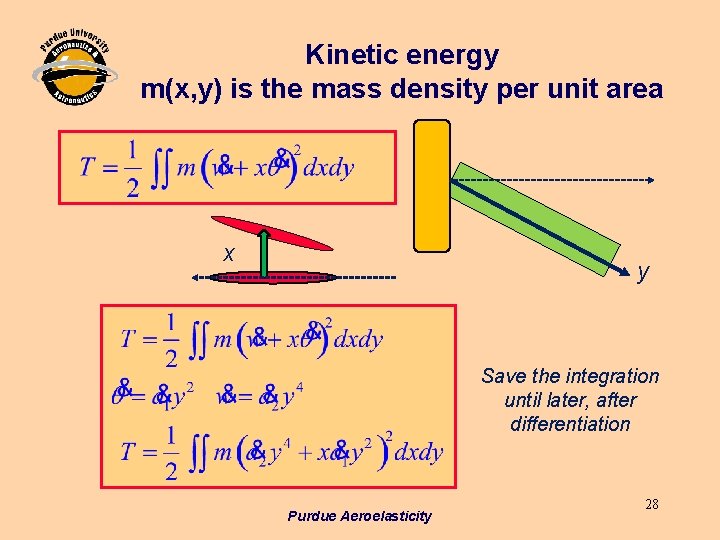

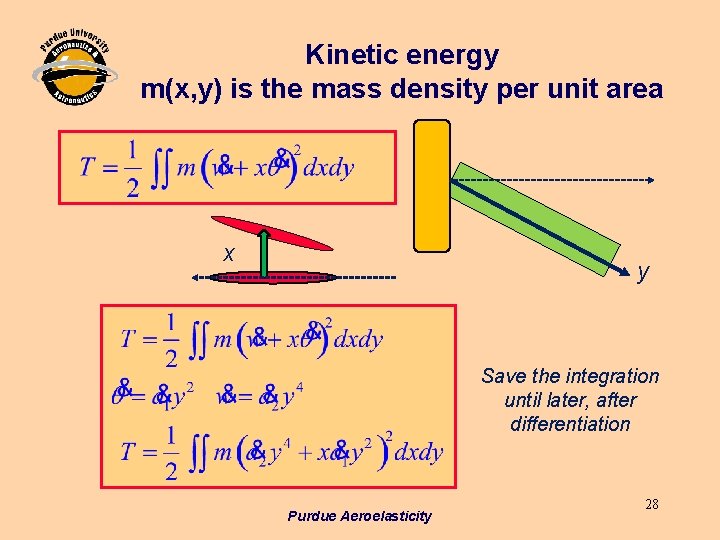

Kinetic energy m(x, y) is the mass density per unit area x y Save the integration until later, after differentiation Purdue Aeroelasticity 28

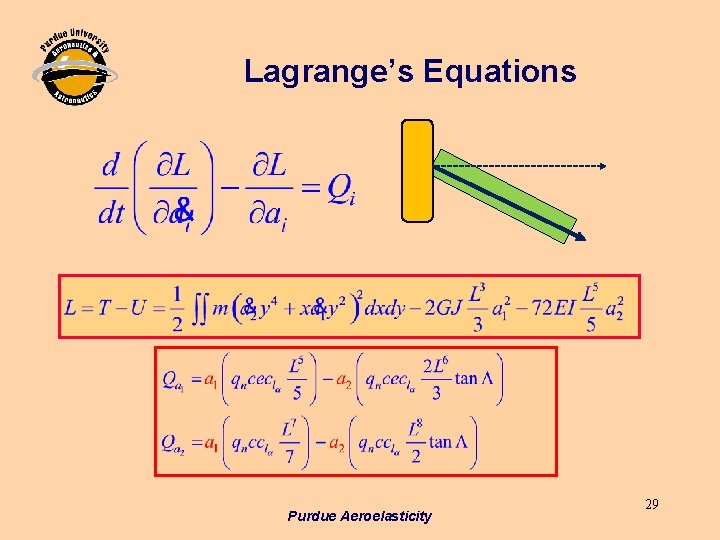

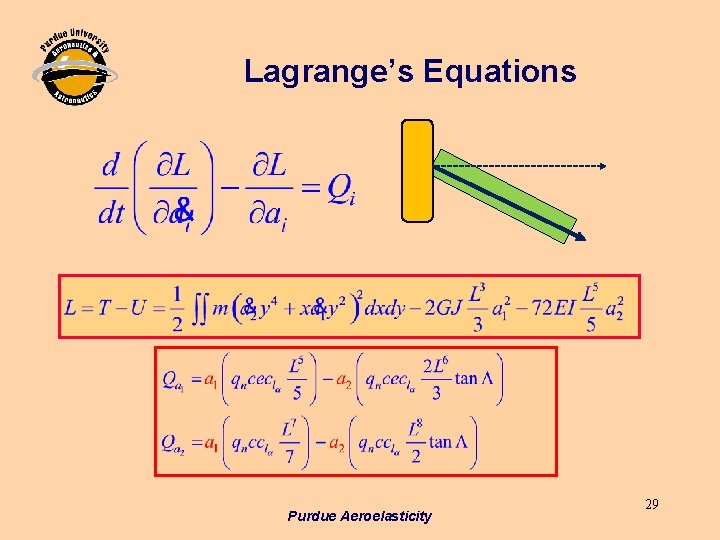

Lagrange’s Equations Purdue Aeroelasticity 29

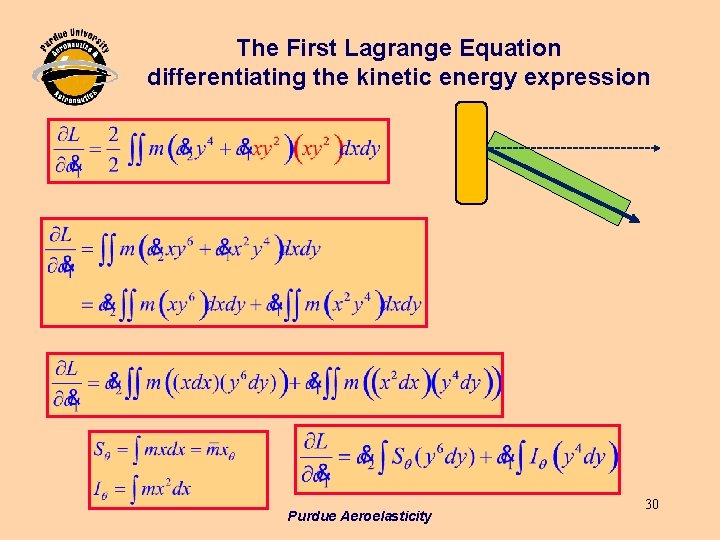

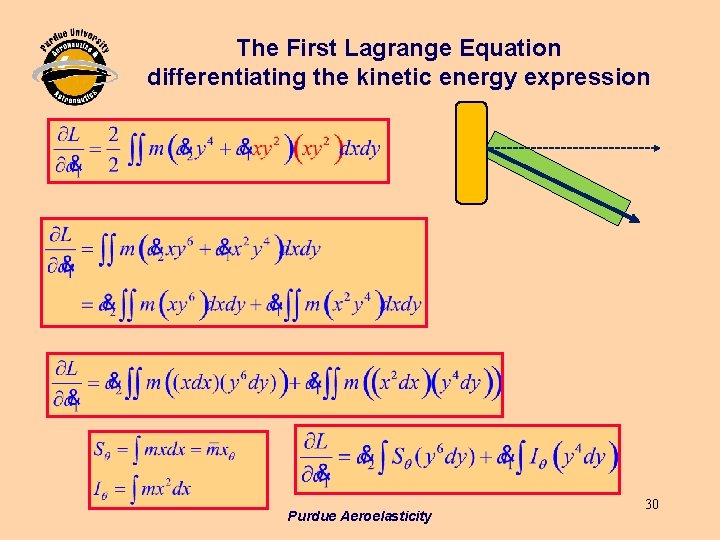

The First Lagrange Equation differentiating the kinetic energy expression Purdue Aeroelasticity 30

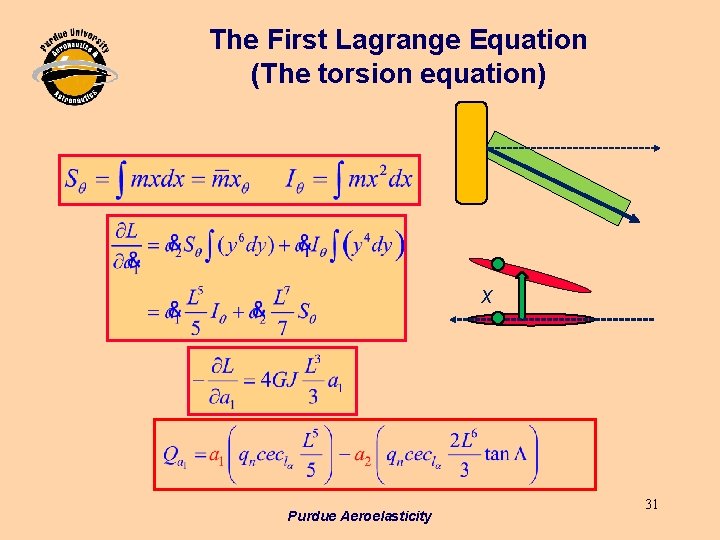

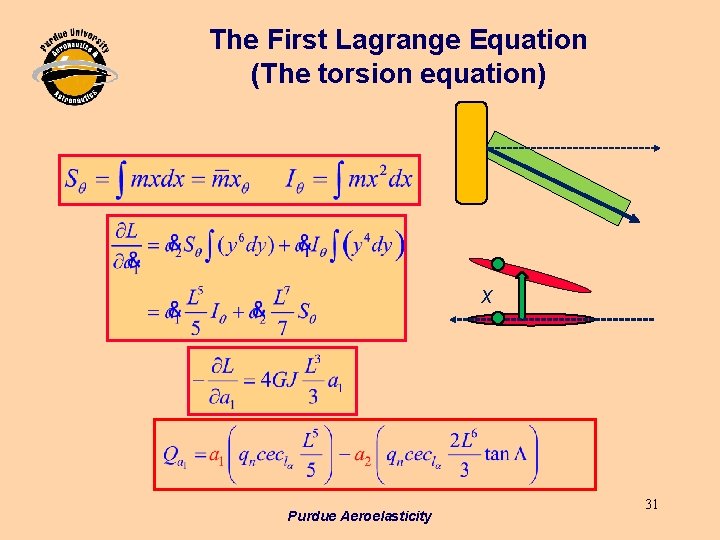

The First Lagrange Equation (The torsion equation) x Purdue Aeroelasticity 31

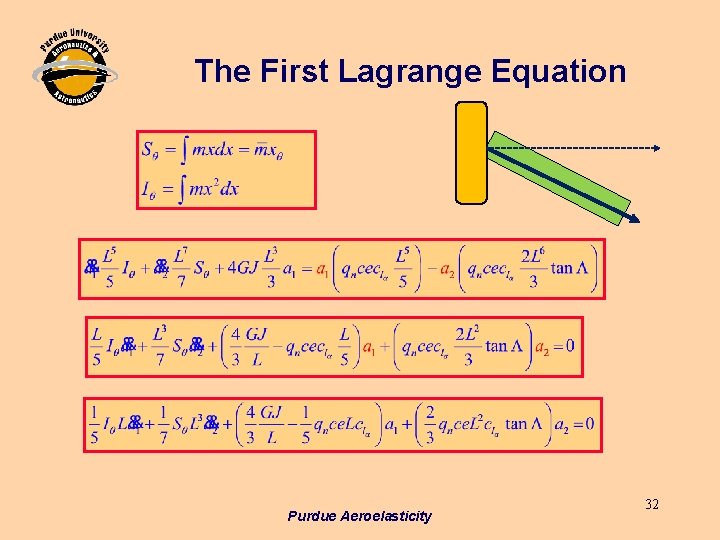

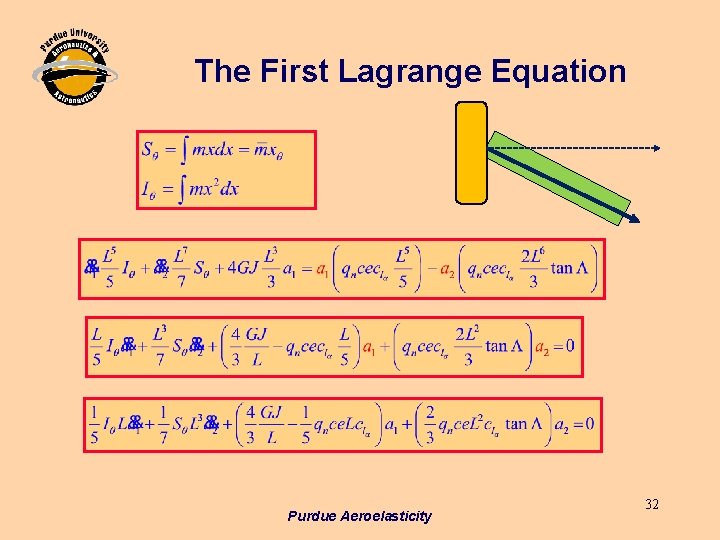

The First Lagrange Equation Purdue Aeroelasticity 32

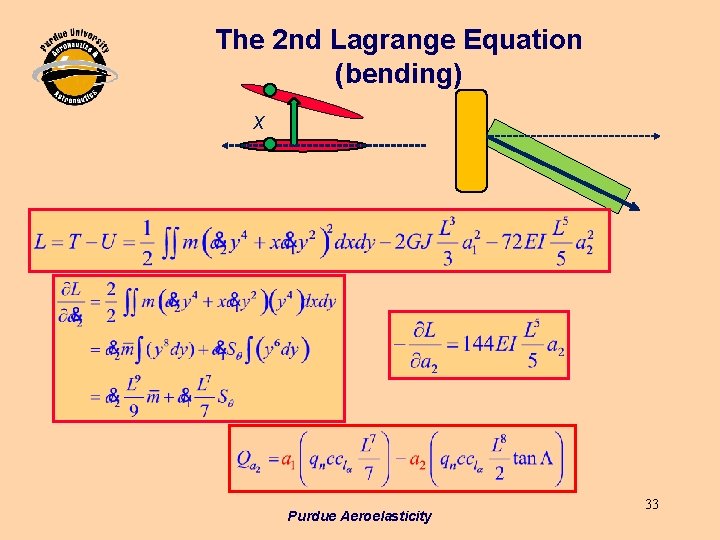

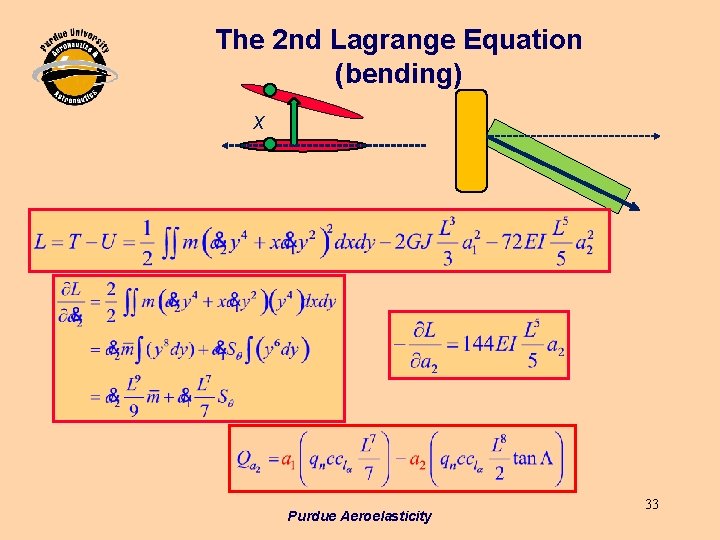

The 2 nd Lagrange Equation (bending) x Purdue Aeroelasticity 33

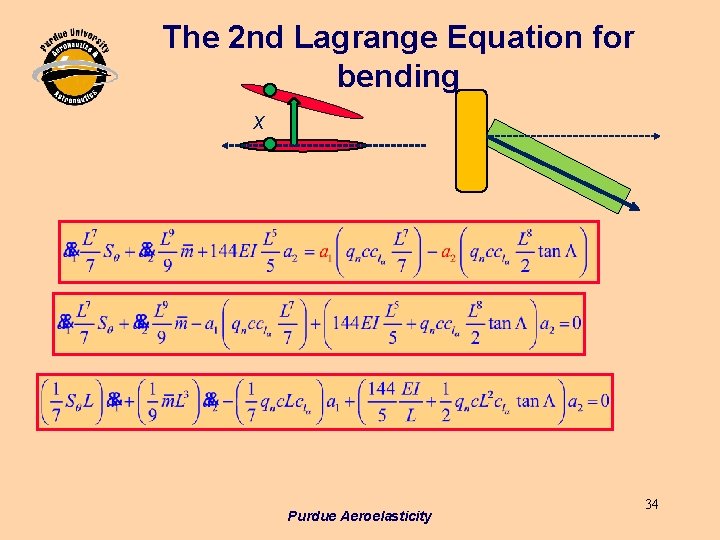

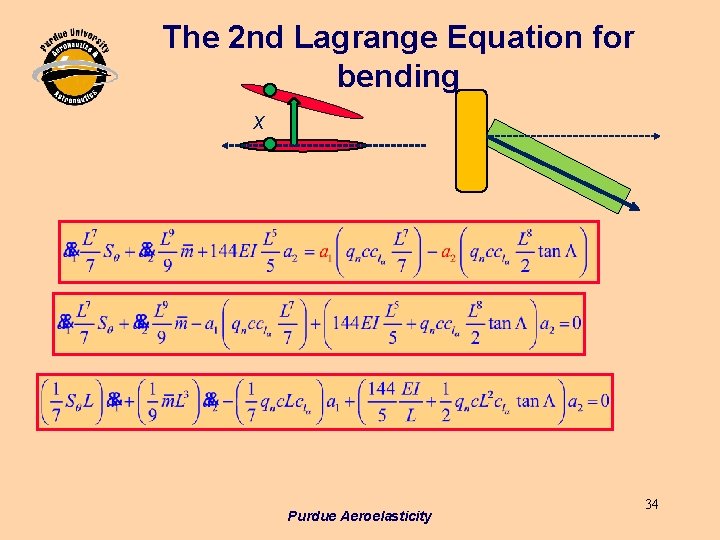

The 2 nd Lagrange Equation for bending x Purdue Aeroelasticity 34

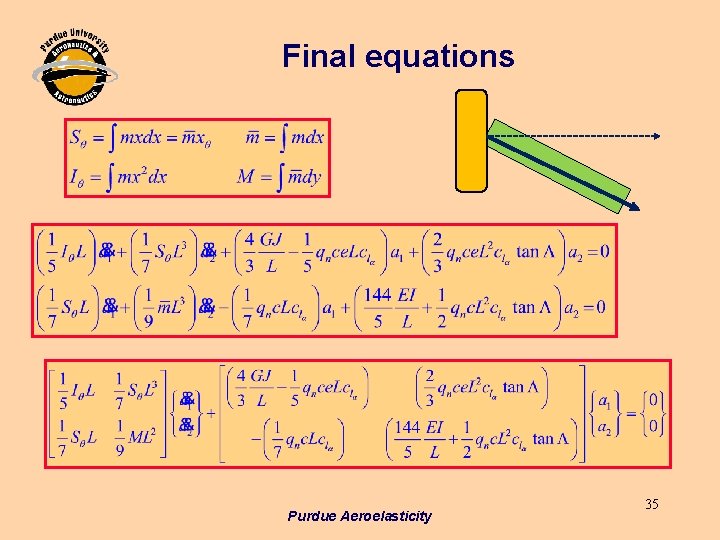

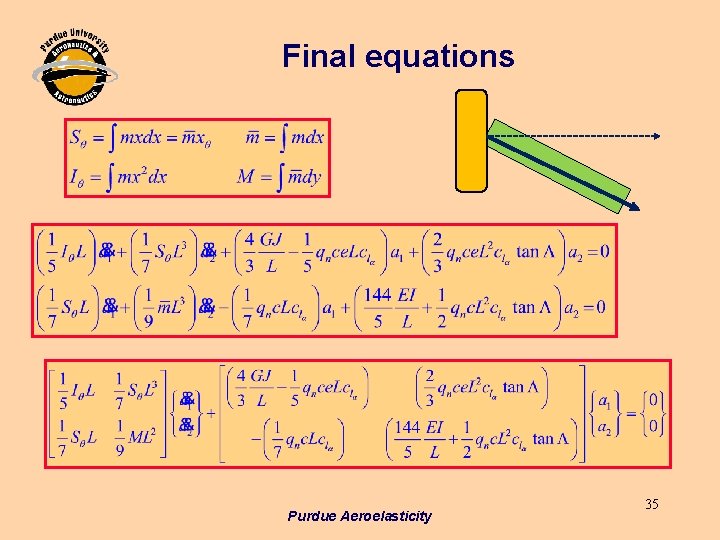

Final equations Purdue Aeroelasticity 35

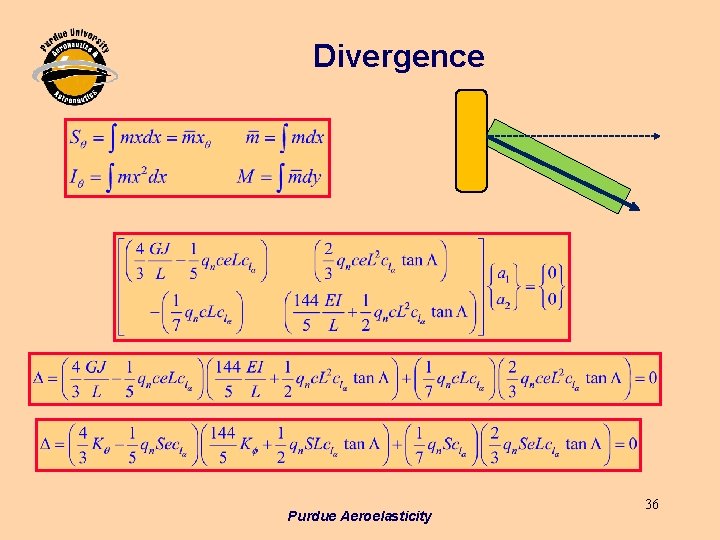

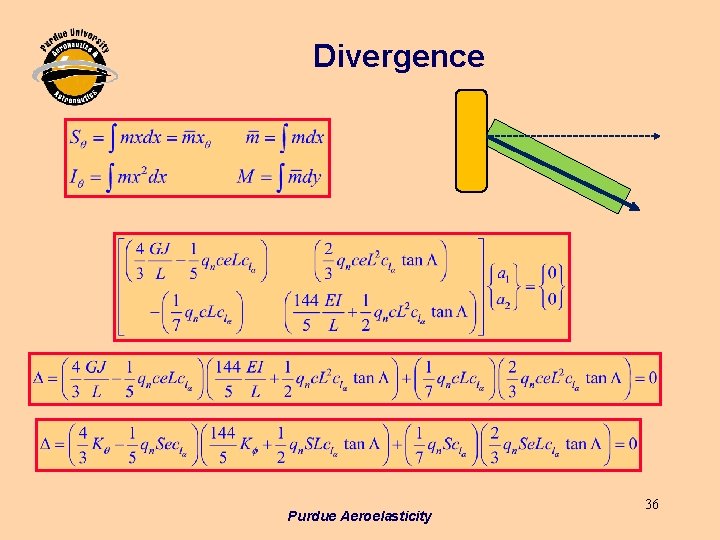

Divergence Purdue Aeroelasticity 36