Lecture4 BIOMECHANICS OF KNEE JOINT Menisci Both menisci

Lecture-4 BIO-MECHANICS OF KNEE JOINT

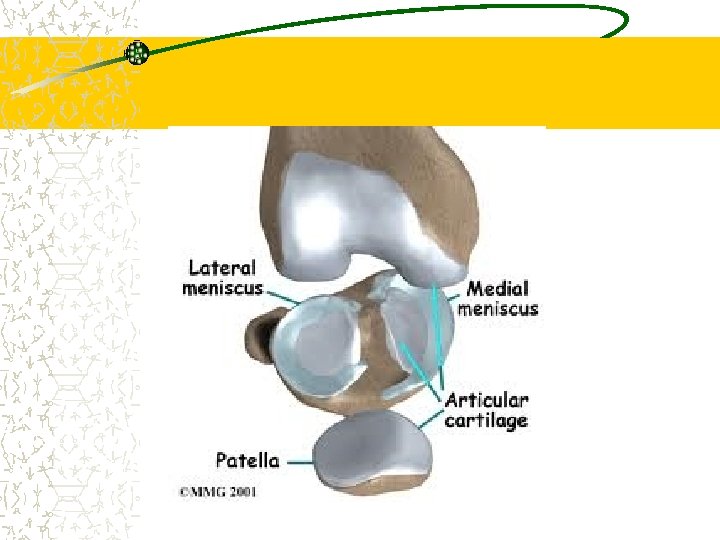

Menisci Both menisci are open toward the intercondylar tubercles thick pheripherally and thin centrally The lateral meniscus covers a greater percentage of smaller lateral tibial surface than the medial meniscus. As a result of its larger surface , the medial condyle has a greater susceptibility to the enormous compressive loads that pass through the medial condyle during routine daily

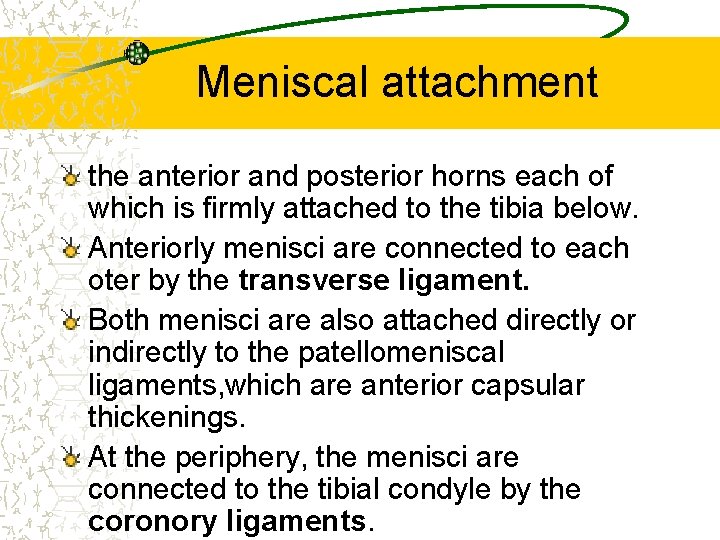

Meniscal attachment the anterior and posterior horns each of which is firmly attached to the tibia below. Anteriorly menisci are connected to each oter by the transverse ligament. Both menisci are also attached directly or indirectly to the patellomeniscal ligaments, which are anterior capsular thickenings. At the periphery, the menisci are connected to the tibial condyle by the coronory ligaments.

Meniscal attachment Medial meniscus attached to medial collateral, anterior cruciate, and posterior cruciate ligaments. The lateral meniscus is also attashed to posterior cruciate ligament.

Roll of meniscus If the round block femoral condyle sits on the flat block tibial plateau, the stress is high because of limited contact. With the addition of menisci, the contact area is increased, and the stress between blocks is reduced.

Joint capsule The joint capsule that encloses the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joint is lax and large. Anterior portion of capsule is firmly attached to inferior aspect of femur and superior portion of the tibia. Posteriorly capsule is attached proximally to the posterior margin of femoral condyles and intercondyler notch and distally to the posterior tibial condyles. The patella, the tendon of the quadriceps muscles superiorly, and the patellar tendon inferiorly complete the anterior portion of the

Joint capsule The anteromedial and anterolateral portions of the capsule, as we shall see, are often separately identified as the medial and lateral patellar retinaculae or together as the extensor retinaculum. The joint capsule is reinforced medially, laterally, and posteriorly by capsular ligaments. The joint capsule is strongly innervated by both nociceptors as well as pacinian and Ruffini corpuscles. These mechanoreceptors may contribute to muscular stabilization of the knee joint by initiating reflex-mediated muscular responses. In addition, the joint capsule is responsible for providing a tight seal for keeping the lubricating synovial fluid within the joint space.

Joint capsule Bony congruence and overall ligament tautness are maximal in full extension, representing the close-packed position of the knee joint. In knee flexion, the periarticular passive structures tend to be lax, and the relative bony incongruence of the joint permits greater anterior and posterior translations, as well as rotation of the tibia beneath the femur.

Joint capsule The joint capsule that encloses the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints is large and lax. It is grossly composed of an exterior or superficial fibrous layer and a thinner internal synovial membrane that is even more complex than the already complex fibrous portion.

Joint capsule The knee joint capsule and its associated ligaments are critical in resisting excessive joint motion to maintain joint integrity and normal function. The joint capsule plays a role beyond that of a simple passive structures.

Synovial layer of joint capsule Synovial layer form the inner lining in much of knee joint capsule. Synovial tissue secrete and absorb synovial fluid into joint for lubrication and to provide nutrition to avascular structures such as meniscus. Posteriorly, the synovium breaks away from the inner wall of the fibrous joint capsule and invaginates anteriorly between the femoral condyles. The invaginated synovium adheres to the anterior aspect and sides of the ACL and the PCL. Therefore, both the ACL and the PCL are contained within the fibrous capsule (intracapsular) but lie outside of the synovial sheath.

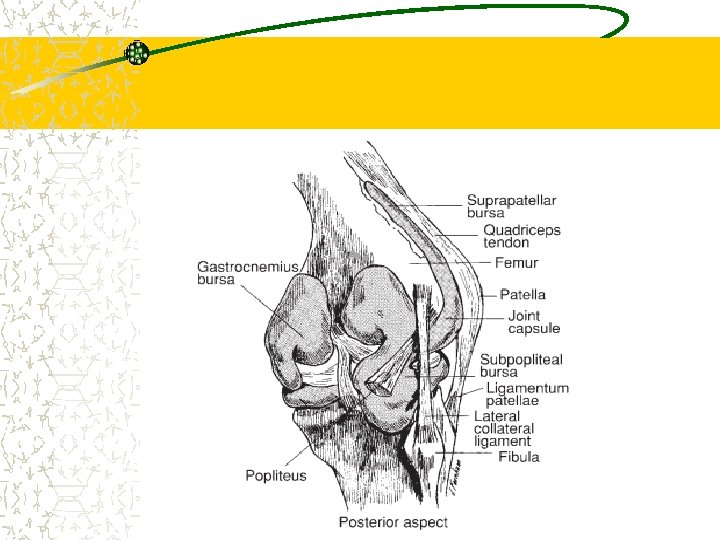

Posterolaterally, the synovial lining delves between the popliteus muscle and lateral femoral condyle. Posteromedially it invaginates between the semimembranosus tendon, the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle, and the medial femoral condyle. The intricate folds of the synovium exclude several fat pads that lie within the fibrous capsule, making them intracapular but extrasynovial, like the cruciate ligaments. The anterior and posterior suprapatellar fat pads lie posterior to the quadriceps tendon and anterior to the distal femoral epiphysis, respectively. The infrapatellar (Hoffa’s) fat pad lies deep to the patellar tendon

Fibrous layer of the joint capsule Superficial to the synovial lining of knee joint lies the fibrous joint capsule. It is composed of two or three layers, depending on location. The anterior portion of knee joint capsule is called extensor retinaculum Fascial layer covers distal quadricep muscle and extend inferiorly. Deep to this layer, medial and lateral retinacula connect patella to surrounding structures.

Cont…. Important band within medial retinacula is medial patellofemoral ligament. Important band in lateral retinacula is lateral patellofemoral lig.

The transversely oriented fibers within the lateral retinaculum, called the lateral patellofemoral ligament, travel from the iliotibial (IT) band to the lateral border of the patella. The remainder of the retinacular bands include the obliquely oriented medial patellomeniscal ligament and the longitudinally positioned medial and

Cont… THE JOINT CAPSULE IS COMPOSED OF: Medially: MCL, vastus medialus n Sartorius. Laterally: IT band its thick fascia lata Posterolaterally: arcuate lig. Posteromedially: posterior oblique lig.

LIGAMENTS OF KNEE JOINT: Function: – resisting or controlling: • 1. excessive knee extension • 2. varus and valgus stresses at the knee (attempted adduction or abduction of the tibia, respectively) • 3. anterior or posterior displacement of the tibia beneath the femur • 4. medial or lateral rotation of the tibia beneath the femur • 5. combinations of anteroposterior displacements and rotations of the tibia, together known as rotatory

Weight-Bearing/Non–Weight-Bearing versus Open/Closed Chain

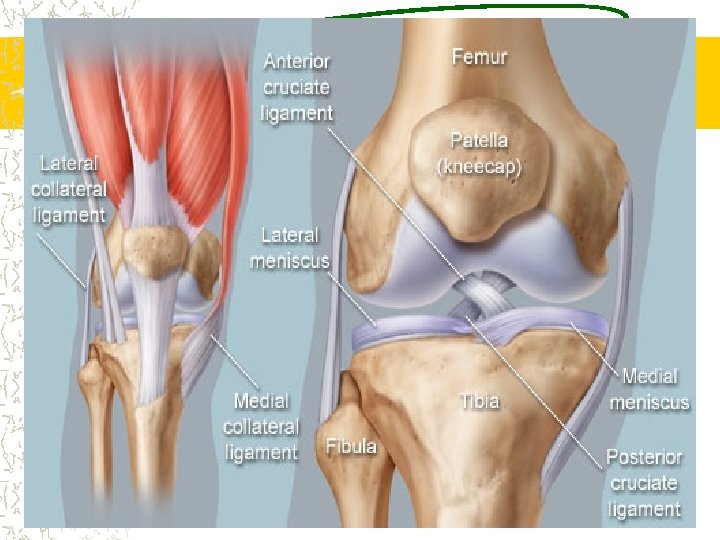

LIGAMENTS OF KNEE JOINT: the main ligaments are, Ø MEDIAL COLLATERAL LIGAMENT Ø LATERAL COLLATERAL LIGAMENT Ø ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT Ø POSTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT

Medial Collateral Ligament ANATOMY: The MCL can be divided into a superficial portion and a deep portion The superficial portion of the MCL arises proximally from the medial femoral epicondyle and travels distally to insert into the medial aspect of the proximal tibia The deep portion of the MCL is continuous with the joint capsule, originates from the inferior aspect of the medial femoral condyle, and inserts on the proximal aspect of the medial tibial plateau.

Biomechanical functions The MCL (superficial) is the primary restraint to excessive abduction (valgus) and lateral rotation stresses at the knee joint. The knee joint is able to resist a valgus stress at full extension because the MCL is taut in this position. In joint flexion the MCL becomes more lax and greater joint space opening is allowed (medially gapping). With the knee flexed, the MCL plays a more critical role in resisting valgus stress despite the permitted

Biomechanical functions The MCL also plays a supportive role in resisting anterior translation of the tibia on the femur in the absence of the primary restraints against anterior tibial translation. The MCL has the capacity to heal when ruptured or damaged, because of its rich blood supply. An isolated injury, therefore, does not often necessitate surgical stabilization but is often left to heal on its own, although this remodeling process can take up to a year

Lateral Collateral Ligament The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is located on the lateral side of the tibiofemoral joint, beginning proximally from the lateral femoral condyle to the fibular head. Joins with the tendon of the biceps femoris muscle to form the conjoined tendon The LCL is an extracapsular ligament. FUNCTIONS: The LCL is primarily responsible for checking varus stresses, and like the MCL, limits varus motion most successfully at full extension

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Anatomy The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) extends from a broad area anterior to and between the intercondylar eminences of the tibia to the posteromedial portion of the lateral femoral condyle. It is composed of two bundles that are named based on their relative attachments on the femur and tibia an anteromedial bundle which is tight in flexion and a posterolateral bundle, which is more convex and tight in extension. ACL ranges from 31 to 38 mm in length and 10 to 12 mm in width

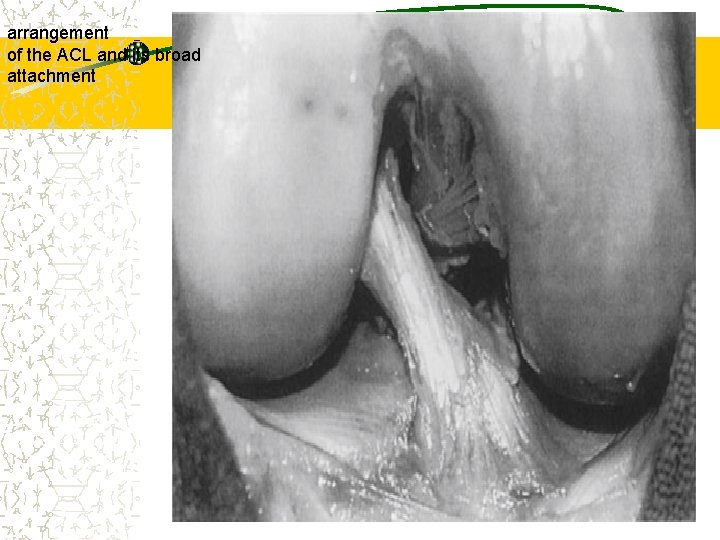

arrangement of the ACL and its broad attachment

Biomechanics of the ACL The ACL functions as the primary restraint against anterior translation (anterior shear) of the tibia on the femur. With the knee in full extension, the PLB is taut; as knee flexion increases, the PLB loosens and the AMB becomes tight. This shift in tension between the bands allows some portion of the ACL to remain tight at all times. In the intact joint, forces producing an anterior translation of the tibia will result in maximal excursion of the tibia at about 30 of flexion, when neither of the ACL bands are particularly tensed. The ACL is also responsible for resisting hyperextension of the knee.

Biomechanics of the ACL In full extension, the ACL absorbs 75% of the anterior translation load and 85% between 30 and 90° of flexion. It acts as a secondary stabilizer against internal rotation of the tibia and valgus angulation at the knee. Loss of the ACL leads to an unstable knee.

ACL can act as a secondary restraint against either varus or valgus motions (adduction and abduction rotations respectively) at the knee. With valgus loading, the lengths of both bands of the ACL increase as knee flexion increases. After injury to the MCL, a valgus moment will increase the strain on the ACL throughout the flexion range. Although the ACL may not make an important contribution to limiting medial rotation of the tibia, medial rotation of the tibia on the femur increases the strain on the AMB of the ACL, with the peak strain occurring between 10 and 15. This is most likely due to the orientation of the ACL, in as much as it winds its way medially around the PCL, becoming tighter

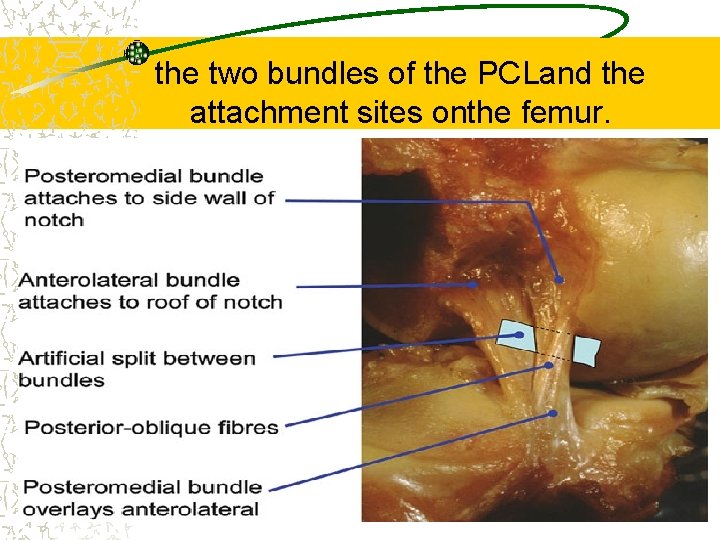

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Anatomy It extends from the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle and projects to a sulcus that is posterior and inferior to the articular plateau of the tibia. The PCL consists of two bundles. a larger antero lateral bundle, which is tight in flexion. a smaller postero medial unit, which is tight in extension.

the two bundles of the PCLand the attachment sites onthe femur.

Biomechanics of the PCL The primary function of the PCL is to resist posterior translation of the tibia on the femur at all positions of knee flexion. The antero lateral band is tight in flexion and is most important in resisting posterior displacement of the tibia in 70– 90° of flexion. The postero medial portion is tight in extension; thus, it resists posterior displacement of the tibia in this position. It is a secondary stabilizer against external rotation of the tibia and excessive varus or valgus angulation at the knee.

- Slides: 35