Lecture Three Whether the suggested target segment is

- Slides: 10

Lecture Three

• Whether the suggested target segment is an appropriate equivalent would depend on circumstances, audience and the type of equivalence envisaged. On a racecourse, the ST phrase might well n ot be so metaphorical and might require more formal equivalence in translation. • The problem of the inevitable subjectivity that the invariant entails ha s been tackled by many scholars. we discuss taxonomic linguistic appr oaches that have attempted to produce a comprehensive model of tr anslation shift analysis. We considers modern descriptive translation studies. Its leading proponent, Gideon Toury, shuns a prescriptive definition of equivalence and, accepting as given that a TT is ‘equivale nt’ to its ST, instead seeks to identify the web of relations between the two. Yet there is still a great deal of practically oriented writing on translation that continues a prescriptive discussion of equivalence. Translator training courses also, perhaps inevitably, tend to have this focus: errors by the trainee translators tend to be corrected prescript ively according to a notion of equivalence held by the tutor.

Vinay • and Influenced by earlier work by the Russian theorist and transl model ator Darbelnet’s Andrei Fedorov (1953), as described by Mossop (2013) and Pym (2016), Vinay and Darbelnet carried out a compara tive stylistic analysis of French and English. They looked at te xts in both languages, noting differences between the langua ges and identifying different translation ‘strategies’ and ‘procedures’. These t erms are sometimes confused in writing about translation. In the technical sense a strategy is an overall orientation of t he translator (e. g. towards ‘free’ or ‘literal’ translation, tow ards the TT or ST, towards domestication or foreignization ) whereas a procedure is a specific technique or method us ed by the translator at a certain point in a text (e. g. the borrowing of a word from the SL, the addition of an explanation or a fo otnote in the TT).

• The two general translation strategies identified by Vinay and Darbelnet • (1995/2004: 128– 37) are (i) direct translation and (ii) oblique translation, • which hark back to the ‘literal vs. free’ division discussed in Chapter 2. Indeed, ‘literal ’ is given by the authors as a synonym for direct translation. The two strategies comprise seven procedures, of which direct translation covers th ree: • (1) Borrowing: The SL word is transferred directly to the TL. This category covers wo rds such as the Russian rouble, datcha, the later glasnost and perestroika, that ar e used in English and other languages to fill a semantic gap in the TL. Sometimes borrowings may be employed to add local colour (sushi, kimo no, Osho–gatsu in a tourist brochure about Japan, for instance). Of course, in some technical fields there is much borrowing of terms ( e. g. computer, internet, from English to Malay). In languages with differing scripts, borrowing entails an additional need for transcription, as in the borrowings of mathematical, scientific and other terms from Arabic into Latin and, later, other languages (e. g. [al- jabr] to algebra).

• (2) Calque: This is ‘a special kind of borrowing’ where the SL expressi on or structure is transferred in a literal translation. For example, t he French calque science-fiction for the English. • Vinay and Darbelnet note that both borrowings and calques often be come fully integrated into the TL, although sometimes with some se mantic change, which can turn them into false friends. An example is the German Handy for a mobile (cell) phone. • (3) Literal translation: This is ‘word-for-word’ translation, which Vinay and Darbelnet describe as being most co mmon between languages of the same family and culture. • Literal translation is the authors’ prescription for good translation: ‘literalness should only be sacrificed because of structural and metalinguistic requirements an d only after checking that the meaning is fully preserved’. But, say Vinay and Darbelnet, the translator may judge literal translation to be ‘unacceptable’ for what are grammatical, syntactic or pragmatic reasons.

• In those cases where literal translation is not possible, Vinay and Dar belnet say that the strategy of oblique translation must be used. Thi s covers a further four procedures: • (4) Transposition: This is a change of one part of speech for another ( e. g. noun for verb) without changing the sense. Transposition can be: • Q obligatory: French dès son lever [‘upon her rising’] in a past cont ext would be translated by as soon as she got up; or • Q optional: in the reverse direction, the English as soon as she got up could be translated into French literally as dès qu’elle s’est levée or as a verb-to-noun transposition in dès son lever [‘upon her rising’]. • Vinay and Darbelnet see transposition as ‘probably the most com mon structural change undertaken by translators’. They list at least ten different categories, such as: • verb A noun: they have pioneered A they have been the first; • adverb A verb: He will soon be back A He will hurry to be back.

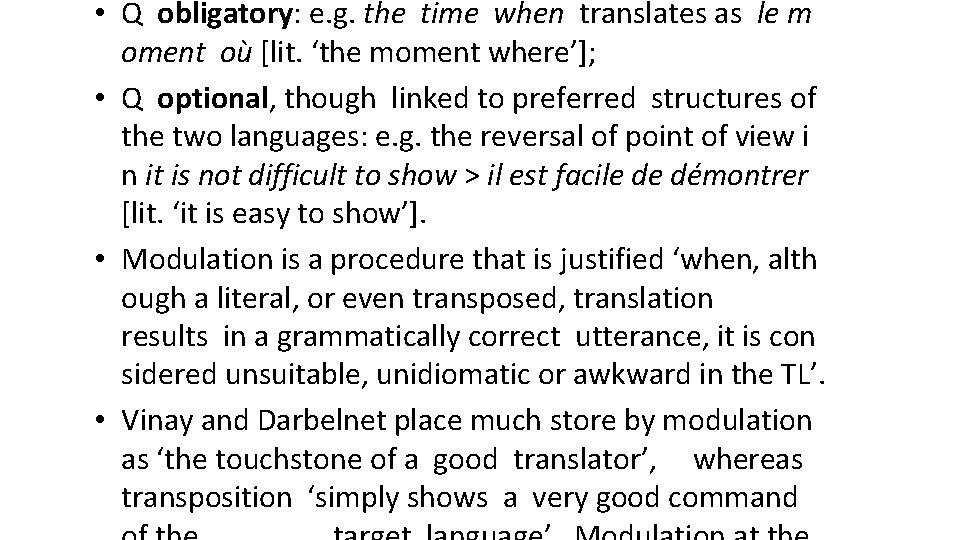

• Q obligatory: e. g. the time when translates as le m oment où [lit. ‘the moment where’]; • Q optional, though linked to preferred structures of the two languages: e. g. the reversal of point of view i n it is not difficult to show > il est facile de démontrer [lit. ‘it is easy to show’]. • Modulation is a procedure that is justified ‘when, alth ough a literal, or even transposed, translation results in a grammatically correct utterance, it is con sidered unsuitable, unidiomatic or awkward in the TL’. • Vinay and Darbelnet place much store by modulation as ‘the touchstone of a good translator’, whereas transposition ‘simply shows a very good command

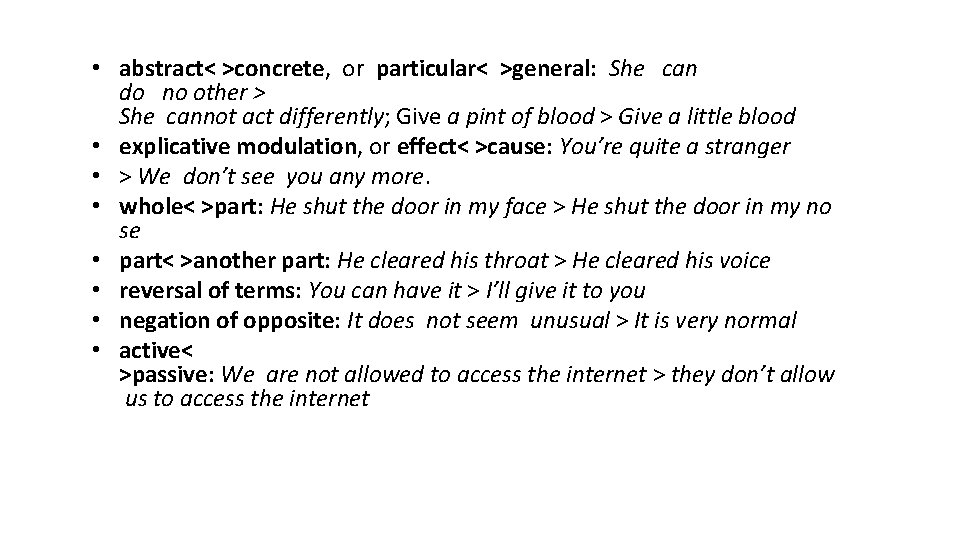

• abstract< >concrete, or particular< >general: She can do no other > She cannot act differently; Give a pint of blood > Give a little blood • explicative modulation, or effect< >cause: You’re quite a stranger • > We don’t see you any more. • whole< >part: He shut the door in my face > He shut the door in my no se • part< >another part: He cleared his throat > He cleared his voice • reversal of terms: You can have it > I’ll give it to you • negation of opposite: It does not seem unusual > It is very normal • active< >passive: We are not allowed to access the internet > they don’t allow us to access the internet

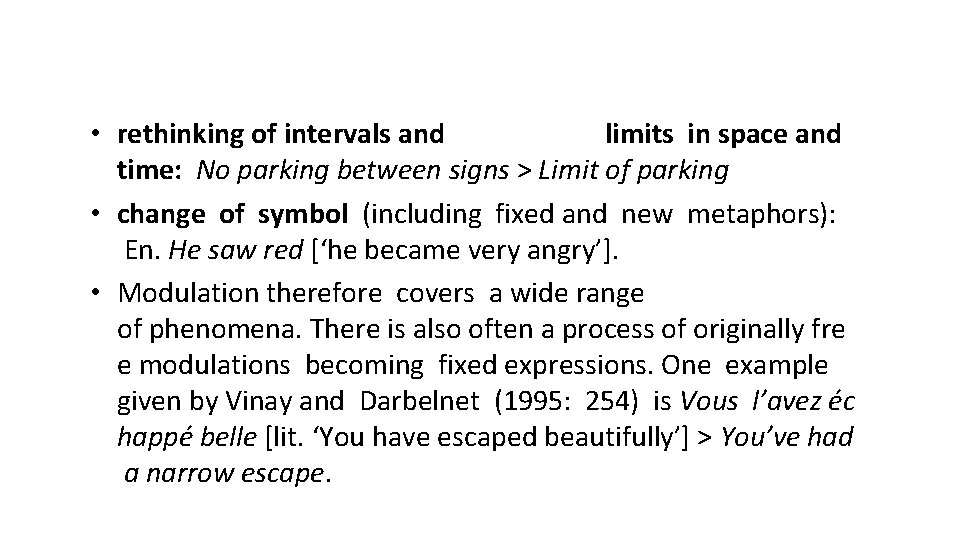

• rethinking of intervals and limits in space and time: No parking between signs > Limit of parking • change of symbol (including fixed and new metaphors): En. He saw red [‘he became very angry’]. • Modulation therefore covers a wide range of phenomena. There is also often a process of originally fre e modulations becoming fixed expressions. One example given by Vinay and Darbelnet (1995: 254) is Vous l’avez éc happé belle [lit. ‘You have escaped beautifully’] > You’ve had a narrow escape.

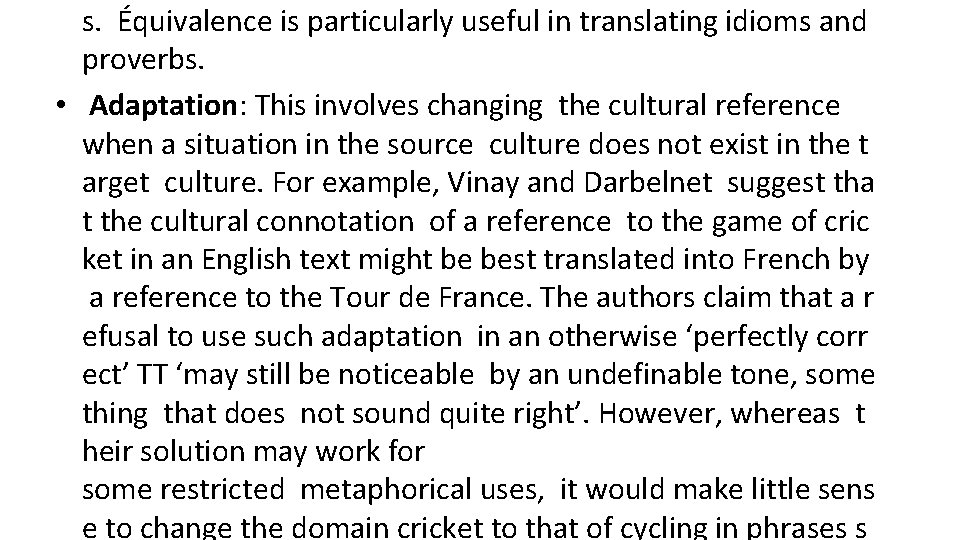

s. Équivalence is particularly useful in translating idioms and proverbs. • Adaptation: This involves changing the cultural reference when a situation in the source culture does not exist in the t arget culture. For example, Vinay and Darbelnet suggest tha t the cultural connotation of a reference to the game of cric ket in an English text might be best translated into French by a reference to the Tour de France. The authors claim that a r efusal to use such adaptation in an otherwise ‘perfectly corr ect’ TT ‘may still be noticeable by an undefinable tone, some thing that does not sound quite right’. However, whereas t heir solution may work for some restricted metaphorical uses, it would make little sens e to change the domain cricket to that of cycling in phrases s