Lecture 7 Jan 28 2002 Chapter 2 The

- Slides: 27

Lecture 7 – Jan 28, 2002

Chapter 2 The Logic of Quantified Statements

Section 2. 1 Predicates and Quantified Statements I

Predicates n A predicate is a sentence that n n n contains a finite number of variables, and becomes a statement when values are substituted for the variables. “x flies like a y. ” n n Let x be “time” and y be “arrow. ” Let x be “fruit” and y be “banana. ”

Domains of Predicate Variables n n The domain D of a predicate variable x is the set of all values that x may take on. Let P(x) be the predicate. x is a free variable. The truth set of P(x) is the set of all values of x D for which P(x) is true.

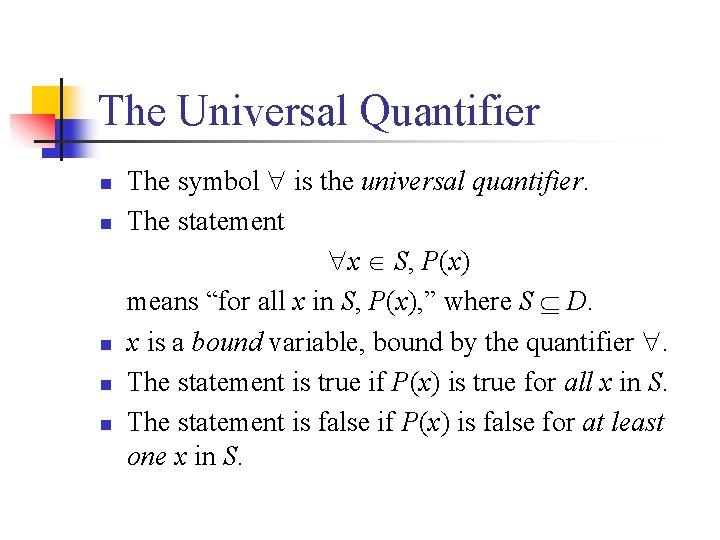

The Universal Quantifier n n n The symbol is the universal quantifier. The statement x S, P(x) means “for all x in S, P(x), ” where S D. x is a bound variable, bound by the quantifier . The statement is true if P(x) is true for all x in S. The statement is false if P(x) is false for at least one x in S.

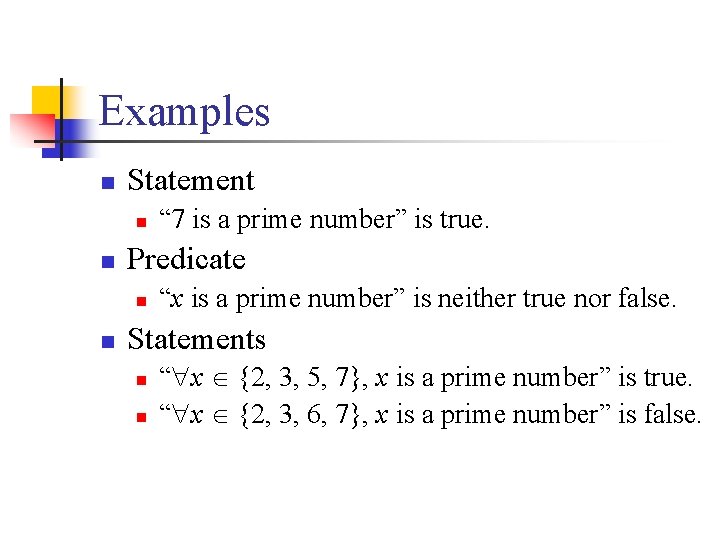

Examples n Statement n n Predicate n n “ 7 is a prime number” is true. “x is a prime number” is neither true nor false. Statements n n “ x {2, 3, 5, 7}, x is a prime number” is true. “ x {2, 3, 6, 7}, x is a prime number” is false.

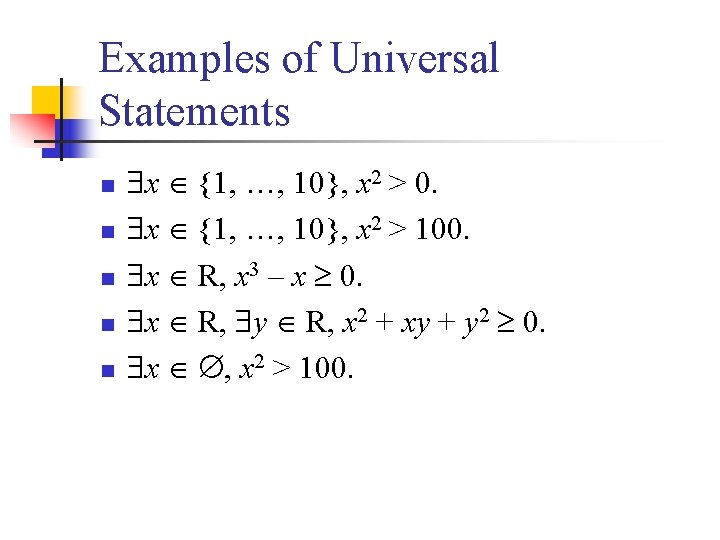

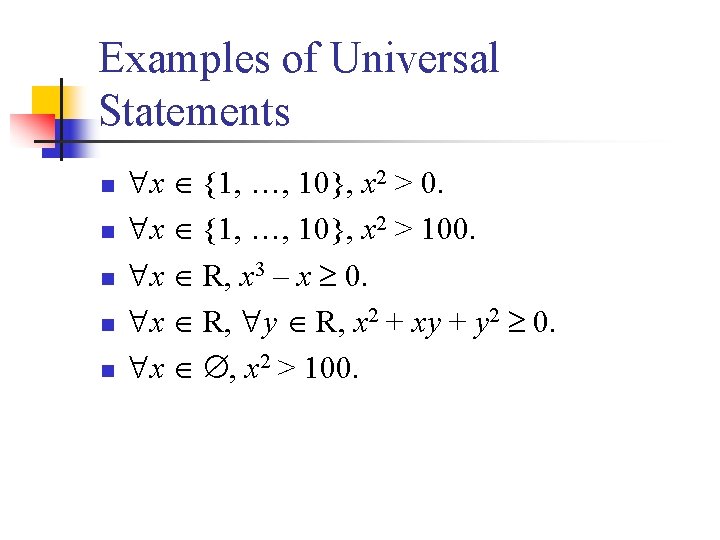

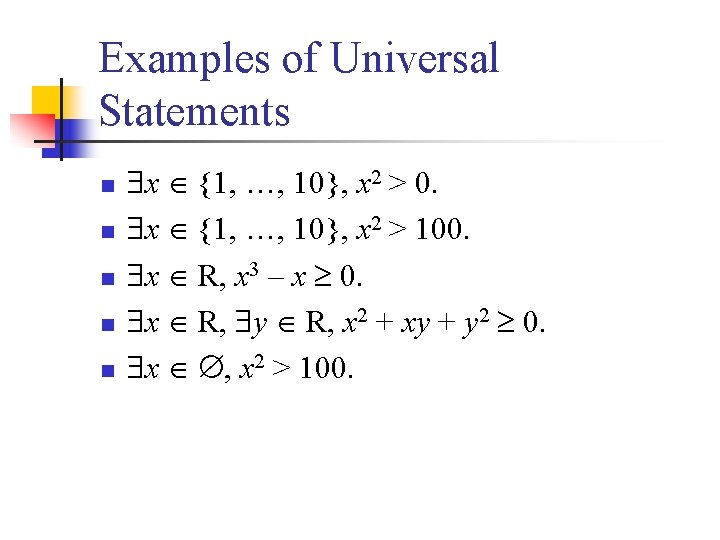

Examples of Universal Statements n n n x {1, …, 10}, x 2 > 0. x {1, …, 10}, x 2 > 100. x R, x 3 – x 0. x R, y R, x 2 + xy + y 2 0. x , x 2 > 100.

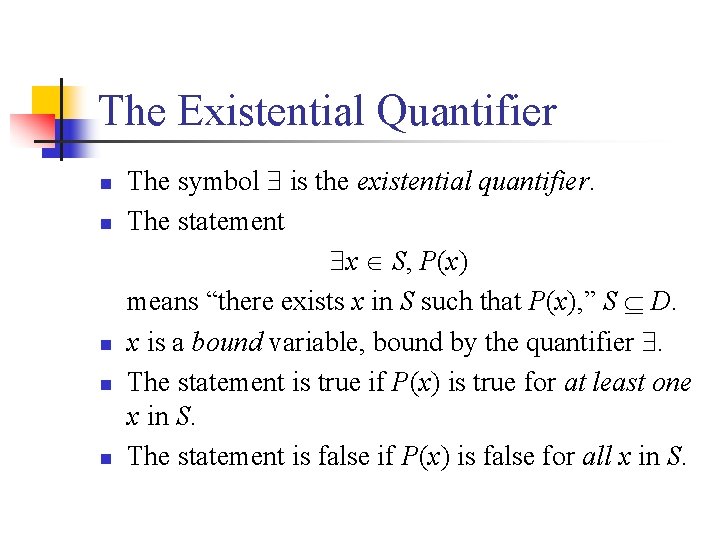

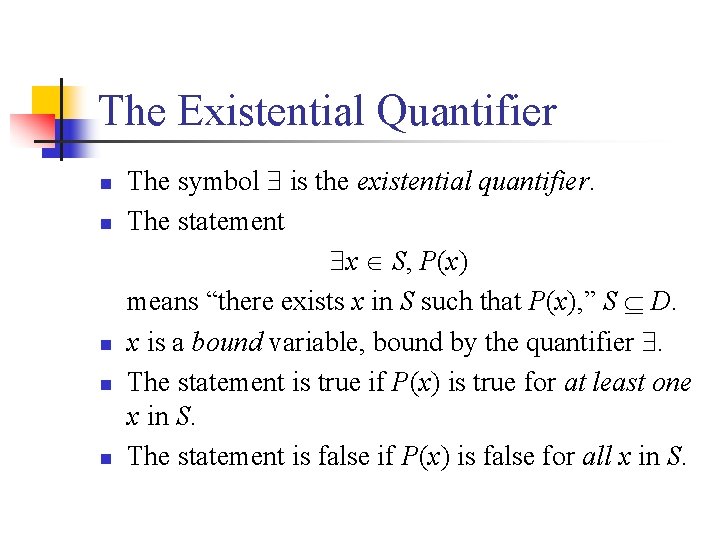

The Existential Quantifier n n n The symbol is the existential quantifier. The statement x S, P(x) means “there exists x in S such that P(x), ” S D. x is a bound variable, bound by the quantifier . The statement is true if P(x) is true for at least one x in S. The statement is false if P(x) is false for all x in S.

Examples of Universal Statements n n n x {1, …, 10}, x 2 > 0. x {1, …, 10}, x 2 > 100. x R, x 3 – x 0. x R, y R, x 2 + xy + y 2 0. x , x 2 > 100.

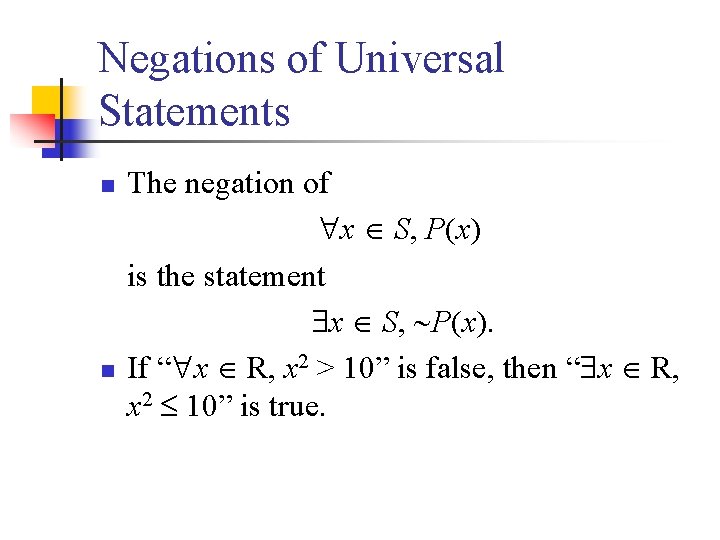

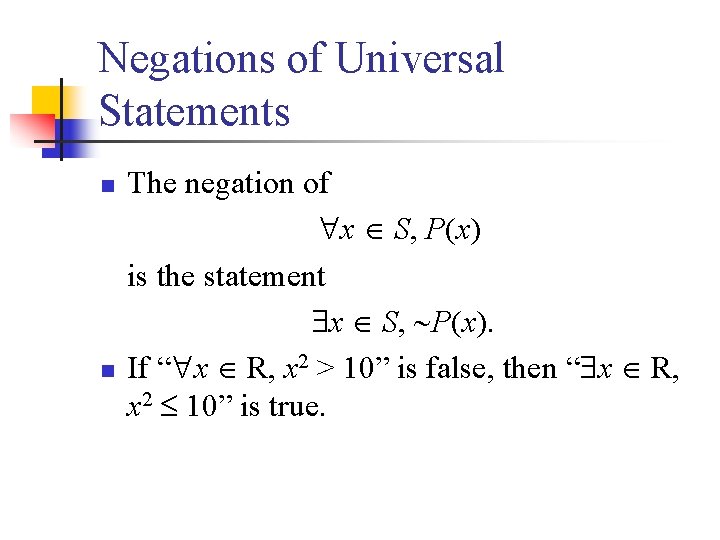

Negations of Universal Statements n n The negation of x S, P(x) is the statement x S, P(x). If “ x R, x 2 > 10” is false, then “ x R, x 2 10” is true.

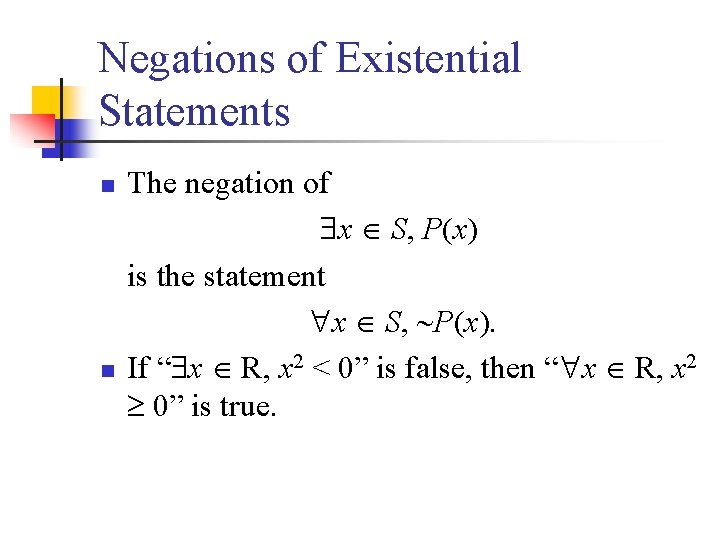

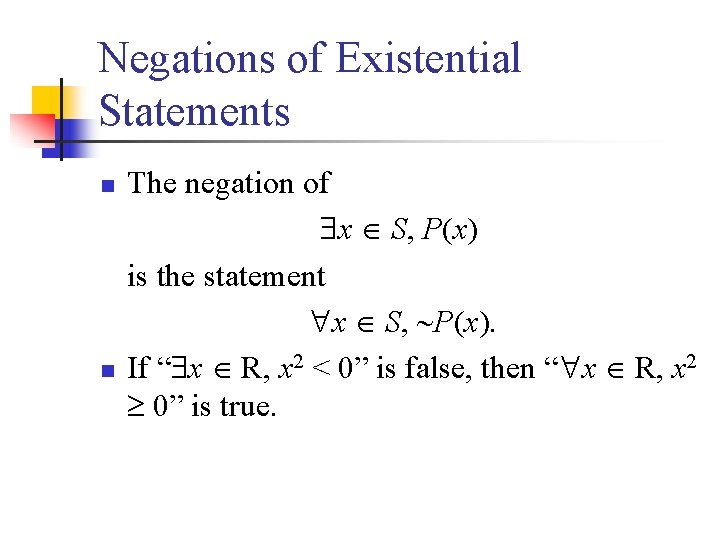

Negations of Existential Statements n n The negation of x S, P(x) is the statement x S, P(x). If “ x R, x 2 < 0” is false, then “ x R, x 2 0” is true.

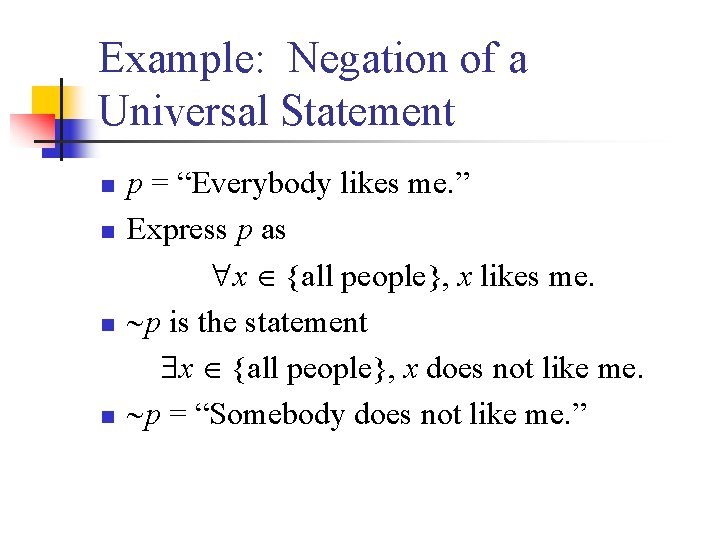

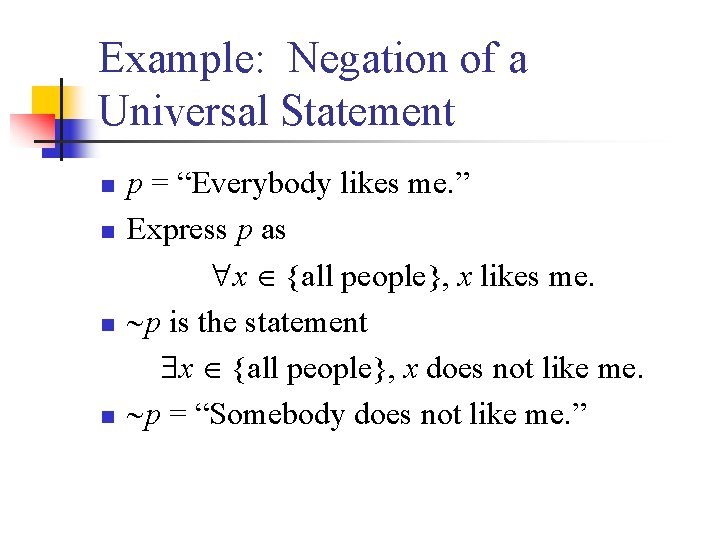

Example: Negation of a Universal Statement n n p = “Everybody likes me. ” Express p as x {all people}, x likes me. p is the statement x {all people}, x does not like me. p = “Somebody does not like me. ”

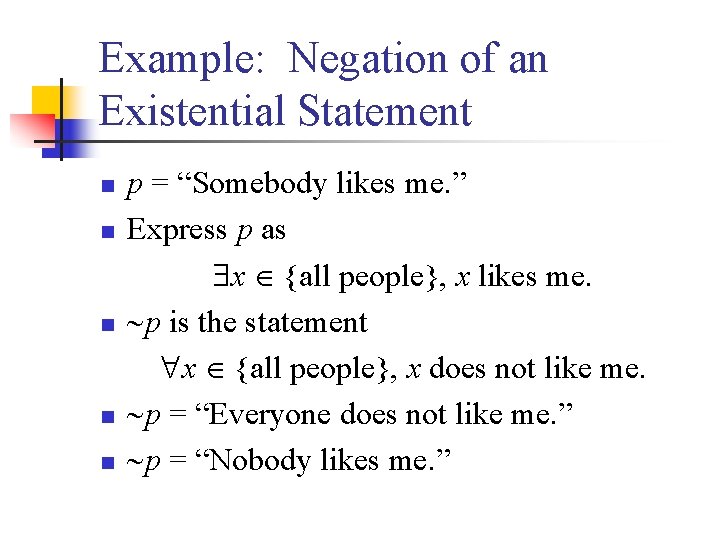

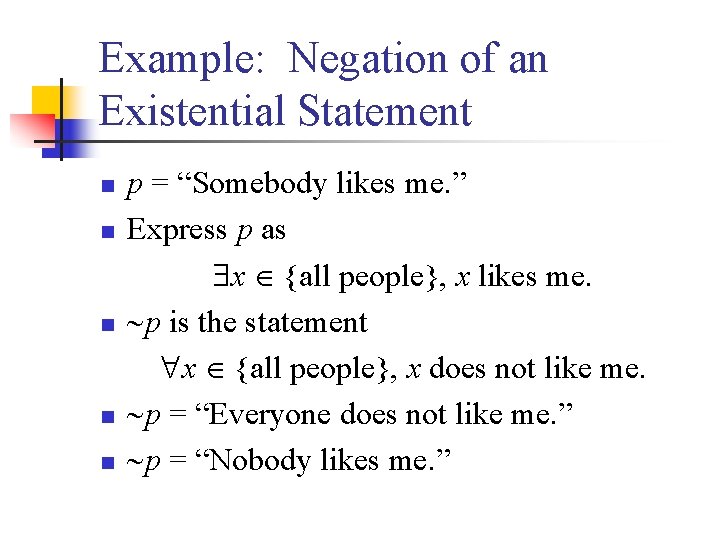

Example: Negation of an Existential Statement n n n p = “Somebody likes me. ” Express p as x {all people}, x likes me. p is the statement x {all people}, x does not like me. p = “Everyone does not like me. ” p = “Nobody likes me. ”

Lecture 8 – Jan 29, 2002

Section 2. 2 Predicates and Quantified Statements II

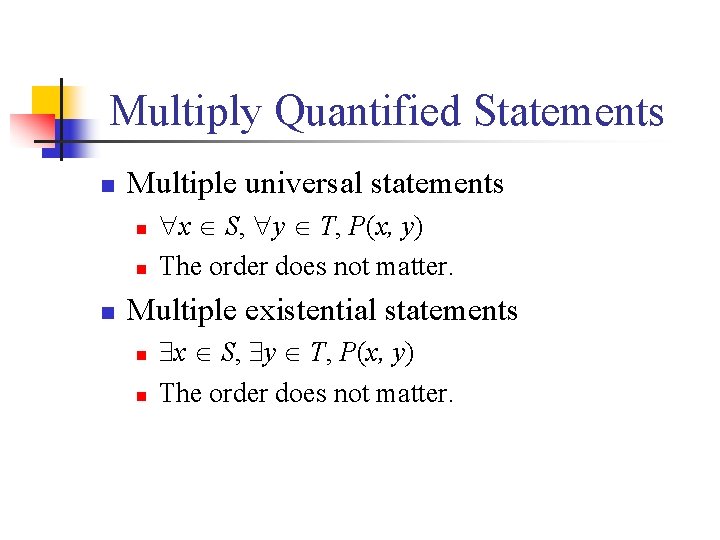

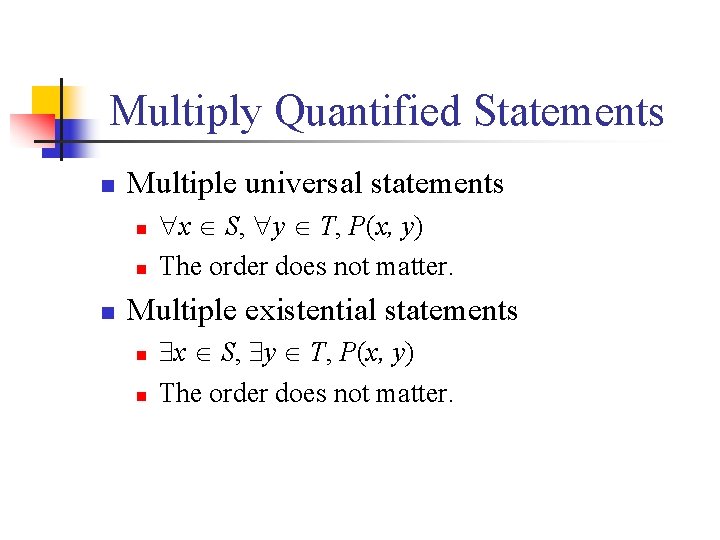

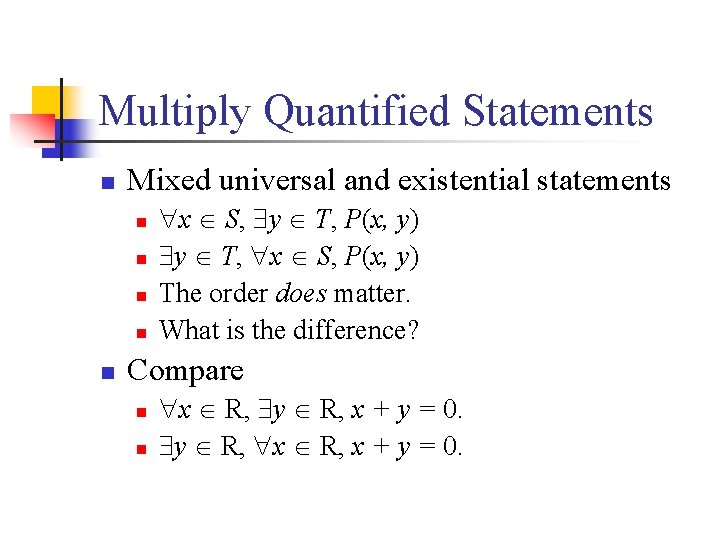

Multiply Quantified Statements n Multiple universal statements n n n x S, y T, P(x, y) The order does not matter. Multiple existential statements n n x S, y T, P(x, y) The order does not matter.

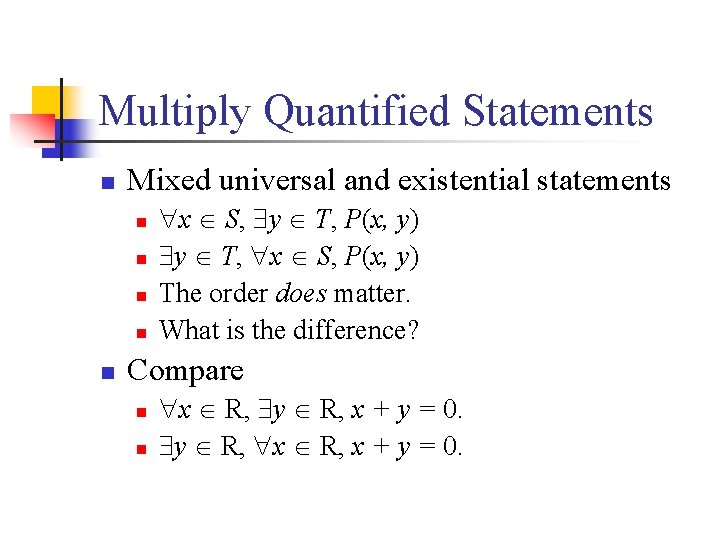

Multiply Quantified Statements n Mixed universal and existential statements n n n x S, y T, P(x, y) y T, x S, P(x, y) The order does matter. What is the difference? Compare n n x R, y R, x + y = 0. y R, x R, x + y = 0.

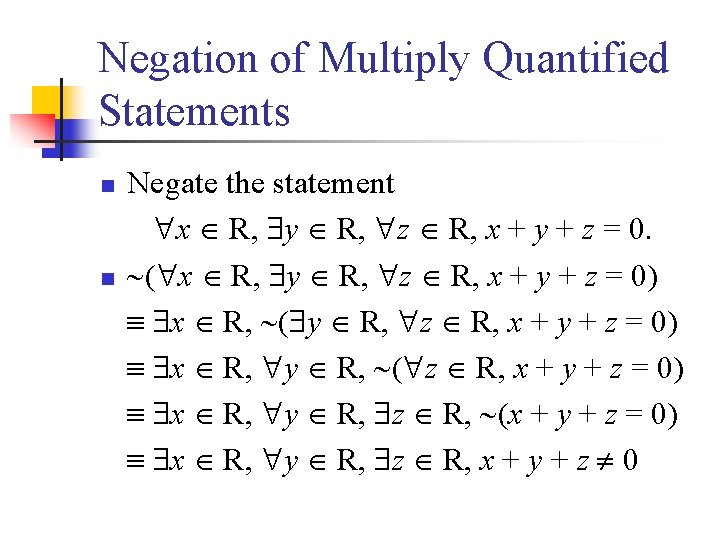

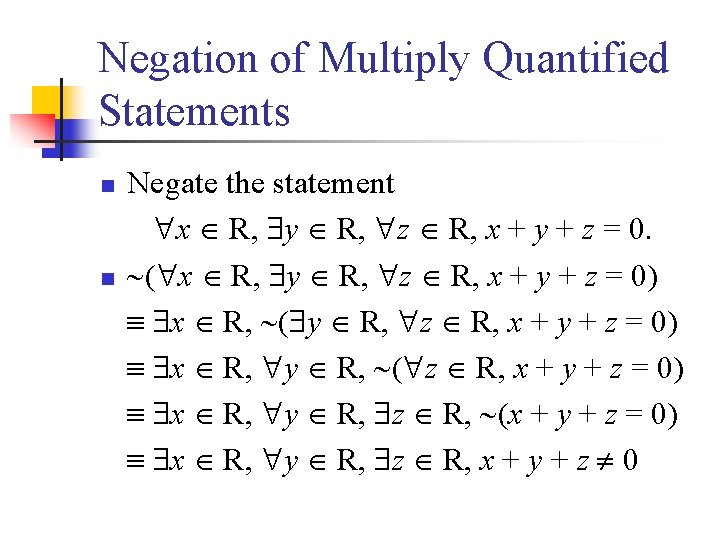

Negation of Multiply Quantified Statements n n Negate the statement x R, y R, z R, x + y + z = 0. ( x R, y R, z R, x + y + z = 0) x R, ( y R, z R, x + y + z = 0) x R, y R, ( z R, x + y + z = 0) x R, y R, z R, (x + y + z = 0) x R, y R, z R, x + y + z 0

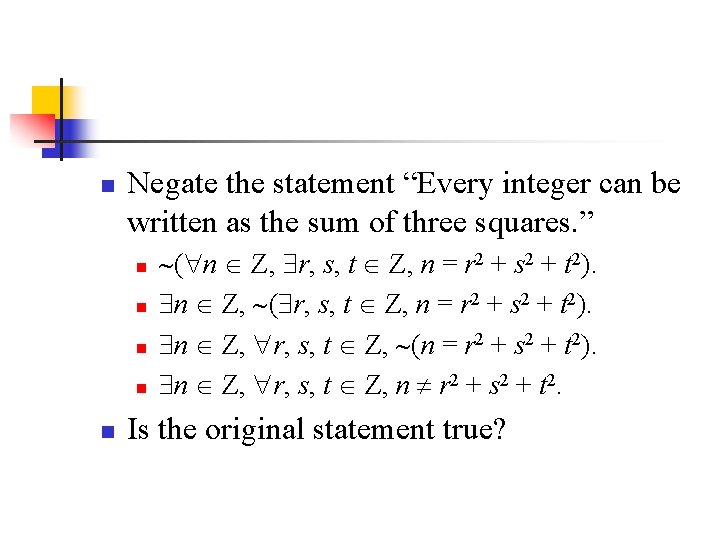

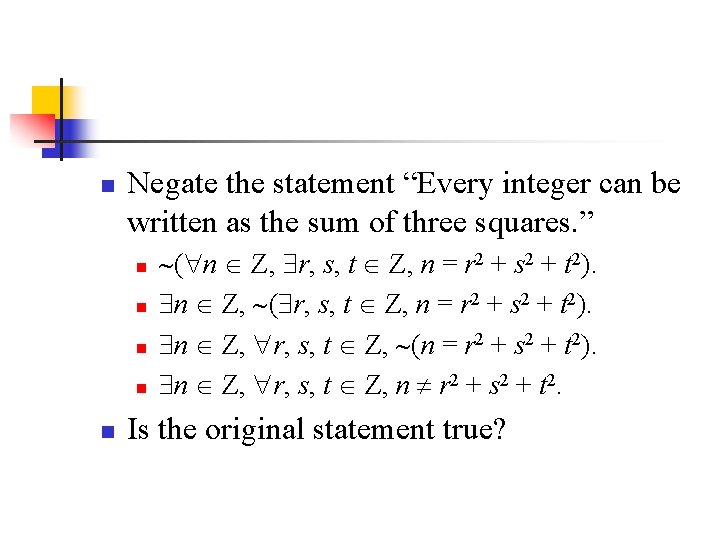

n Negate the statement “Every integer can be written as the sum of three squares. ” n n n ( n Z, r, s, t Z, n = r 2 + s 2 + t 2). n Z, ( r, s, t Z, n = r 2 + s 2 + t 2). n Z, r, s, t Z, (n = r 2 + s 2 + t 2). n Z, r, s, t Z, n r 2 + s 2 + t 2. Is the original statement true?

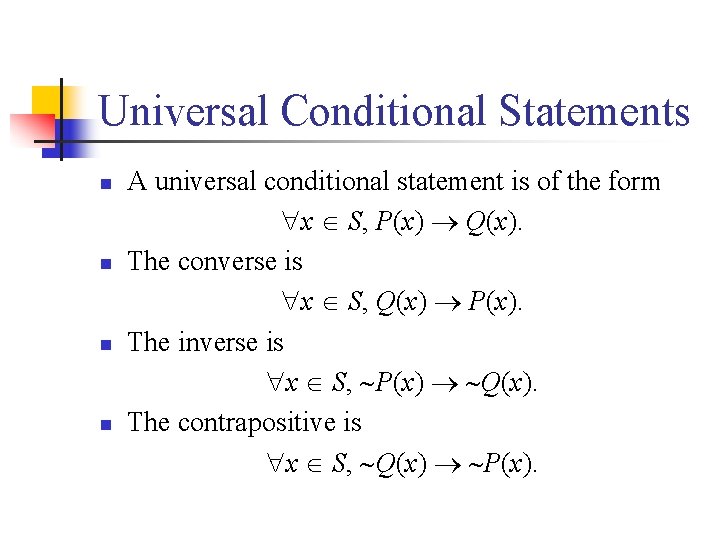

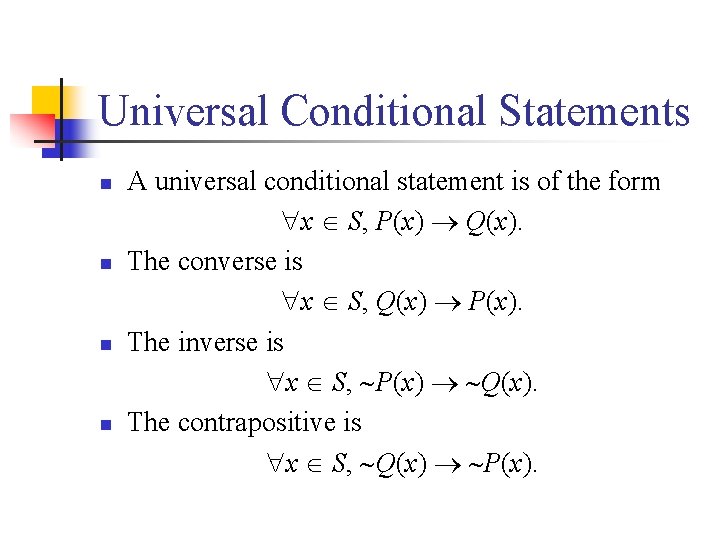

Universal Conditional Statements n n A universal conditional statement is of the form x S, P(x) Q(x). The converse is x S, Q(x) P(x). The inverse is x S, P(x) Q(x). The contrapositive is x S, Q(x) P(x).

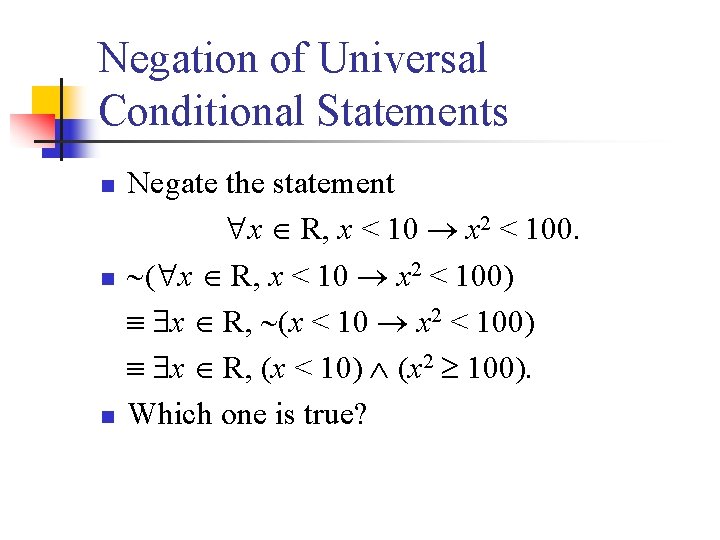

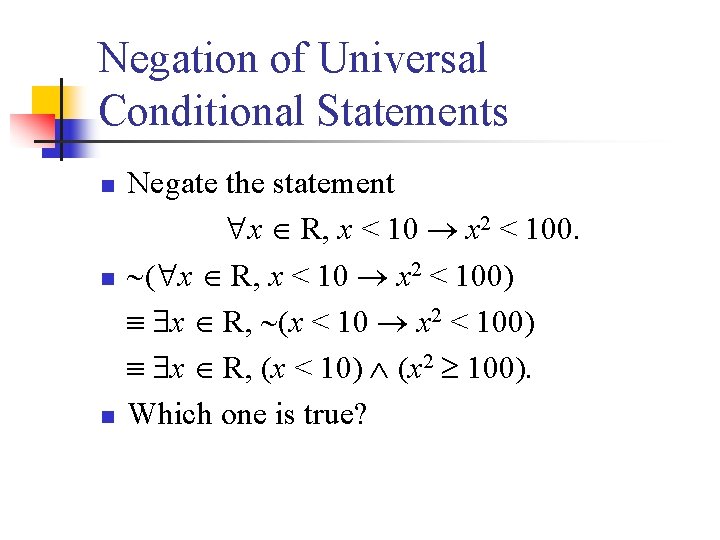

Negation of Universal Conditional Statements n n n Negate the statement x R, x < 10 x 2 < 100. ( x R, x < 10 x 2 < 100) x R, (x < 10 x 2 < 100) x R, (x < 10) (x 2 100). Which one is true?

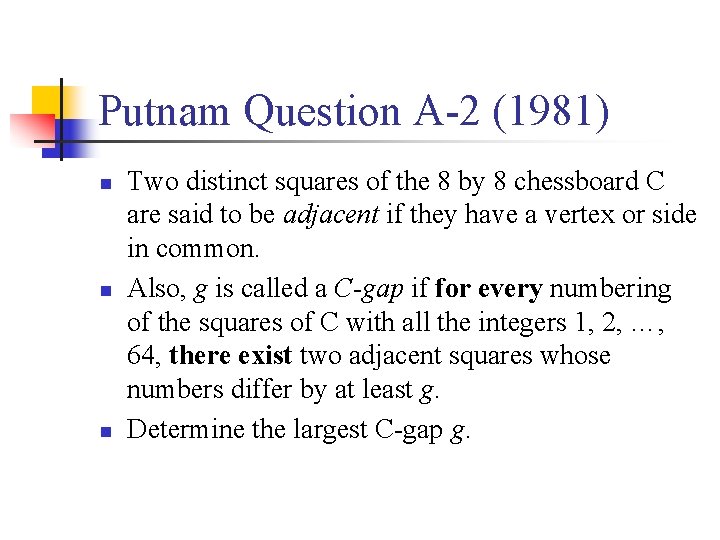

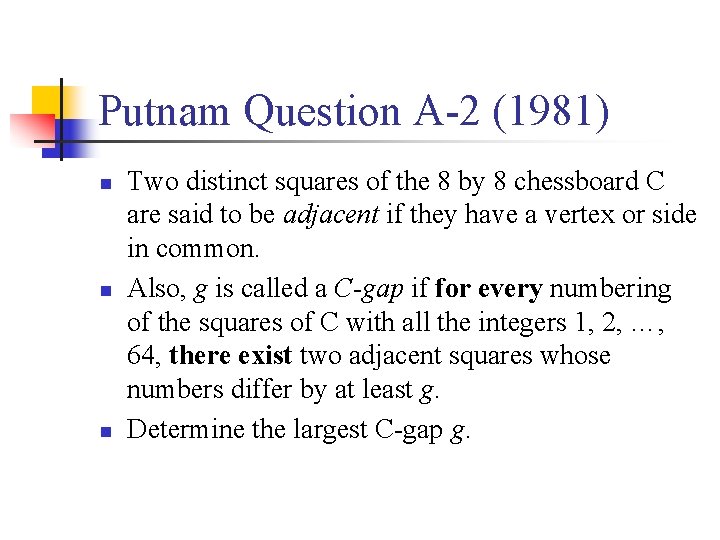

Putnam Question A-2 (1981) n n n Two distinct squares of the 8 by 8 chessboard C are said to be adjacent if they have a vertex or side in common. Also, g is called a C-gap if for every numbering of the squares of C with all the integers 1, 2, …, 64, there exist two adjacent squares whose numbers differ by at least g. Determine the largest C-gap g.

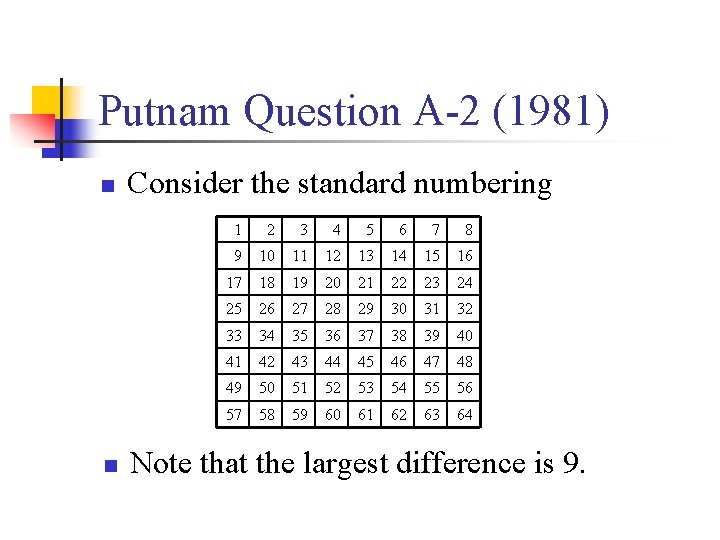

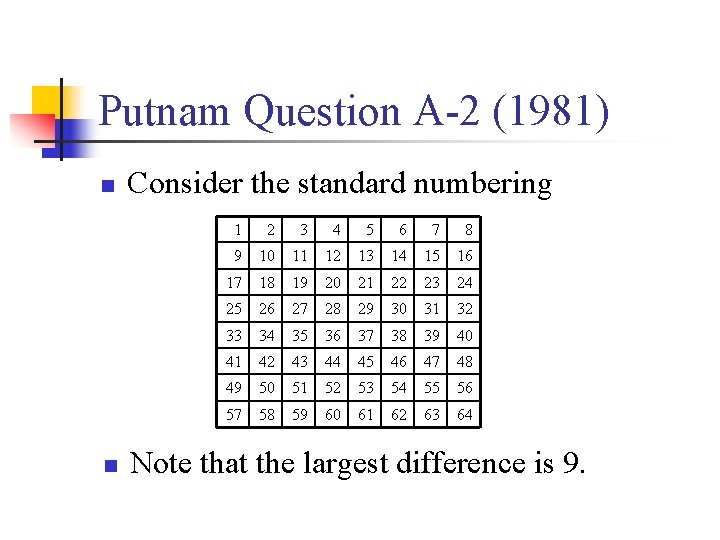

Putnam Question A-2 (1981) n n Consider the standard numbering 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 Note that the largest difference is 9.

Putnam Question A-2 (1981) n n Could the answer be 9? 9 is the largest C-gap if n n 9 is a C-gap, and 10 is not a C-gap.

Putnam Question A-2 (1981) n 10 is not a C-gap if n n There exists a numbering of the squares such that no two adjacent squares differ by at least 10. Equivalently, there exists a numbering of the squares such that every two adjacent squares differ by at most 9. We have just seen that this is true. Therefore, 10 is not a C-gap.

Putnam Question A-2 (1981) n Is 9 a C-gap? n n Consider the two squares that are labeled #1 and #64. There is a path of at most 8 squares linking square #1 and square #64. Of the 7 differences along this path, one must be at least 9, since the total difference is 63. Therefore, 9 is a C-gap.