Lecture 6 Bayesian Inference and Molecular Dating Thomas

Lecture 6 Bayesian Inference and Molecular Dating Thomas Bayes

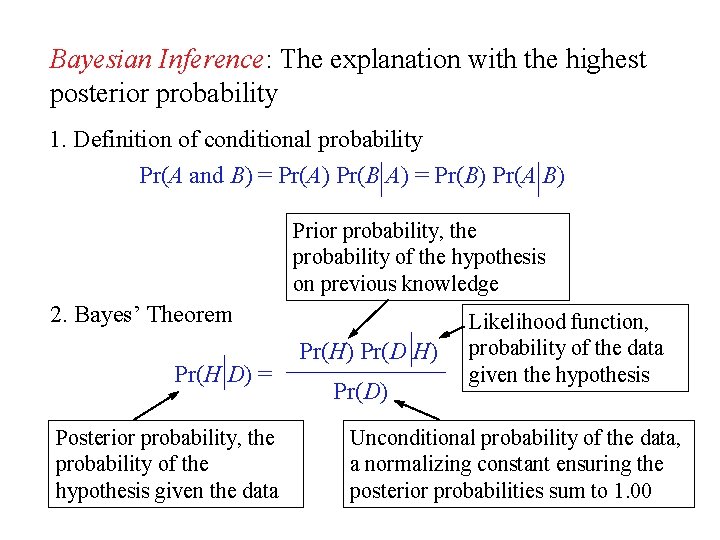

Bayesian Inference: The explanation with the highest posterior probability 1. Definition of conditional probability Pr(A and B) = Pr(A) Pr(B A) = Pr(B) Pr(A B) Prior probability, the probability of the hypothesis on previous knowledge 2. Bayes’ Theorem Pr(H D) = Posterior probability, the probability of the hypothesis given the data Pr(H) Pr(D) Likelihood function, probability of the data given the hypothesis Unconditional probability of the data, a normalizing constant ensuring the posterior probabilities sum to 1. 00

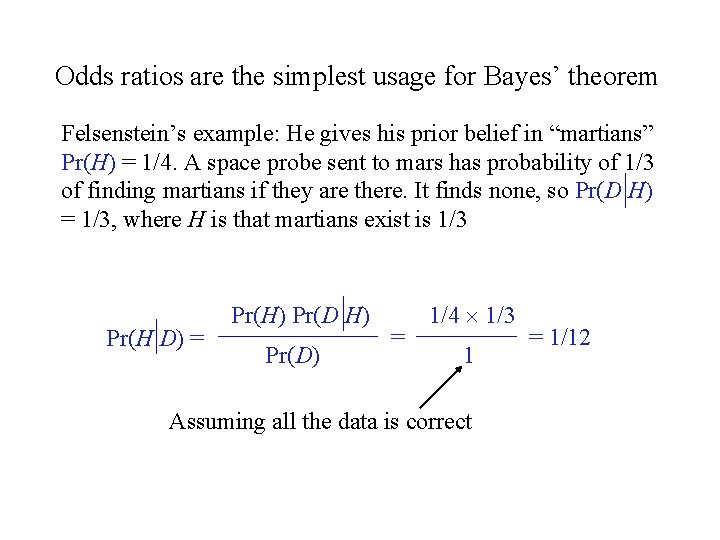

Odds ratios are the simplest usage for Bayes’ theorem Felsenstein’s example: He gives his prior belief in “martians” Pr(H) = 1/4. A space probe sent to mars has probability of 1/3 of finding martians if they are there. It finds none, so Pr(D H) = 1/3, where H is that martians exist is 1/3 Pr(H D) = Pr(H) Pr(D) = 1/4 1/3 1 Assuming all the data is correct = 1/12

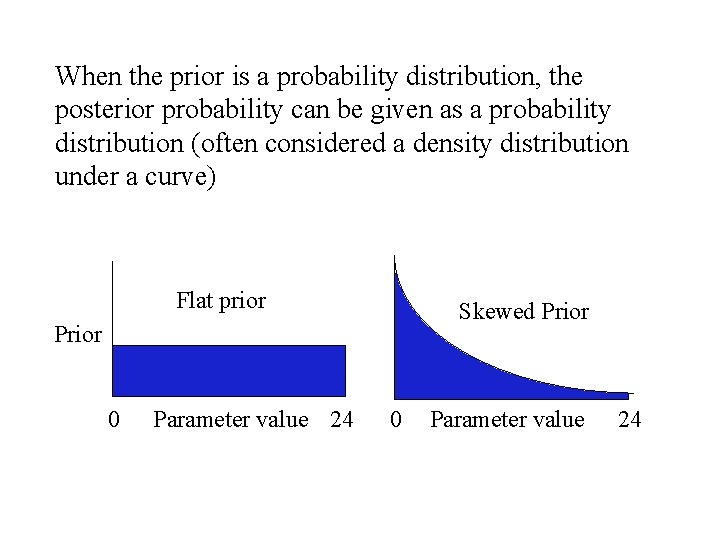

When the prior is a probability distribution, the posterior probability can be given as a probability distribution (often considered a density distribution under a curve) Flat prior Skewed Prior 0 Parameter value 24

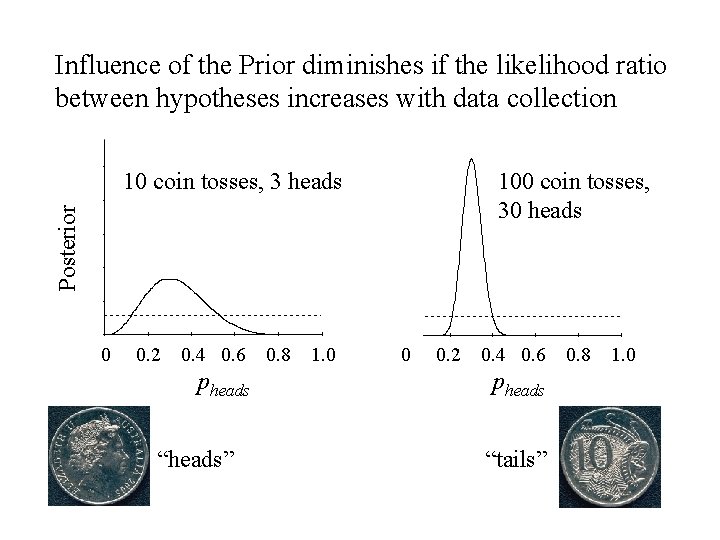

Influence of the Prior diminishes if the likelihood ratio between hypotheses increases with data collection 100 coin tosses, 30 heads Posterior 10 coin tosses, 3 heads 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 pheads “heads” 0. 8 1. 0 0 0. 2 0. 4 0. 6 pheads “tails” 0. 8 1. 0

Bayesian inference in phylogenetics First use in phylogenetics: Li (1996, Ph. D thesis), Rannala and Yang (1996) Tree 1 Tree 2 Tree 3 Posterior Prior Likelihood A useful property of Bayesian inference for phylogenetics is that with flat priors (all hypotheses equal before the data is examined), posterior probabilities for two trees are proportional to their likelihood ratio. Tree 1 Tree 2 Tree 3

Bayesian inference in phylogenetic notation Prior distribution Posterior distribution (ti D) = Where Likelihood distribution (ti) (D ti) TJ=1 (tj) (D tj) (D ti) = b ti = Treei = substitution model b = branch-length (D ti, b, ) (b, ) dbd Summing over this integral becomes too complex with so many tree/parameter hypotheses

Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis New state rejected Tree 1 Tree 2 Tree 3 Generation: 1 New state accepted The chain 2 3 4 5 6 Bayesian Posterior Probability for Tree 1 (BPPtree 1)= 4/6 Sampling the MCMC provides a valid approximation for the posterior distribution of trees (over 100, 000 s – 1, 000 s of generations) - without having to know the denominator

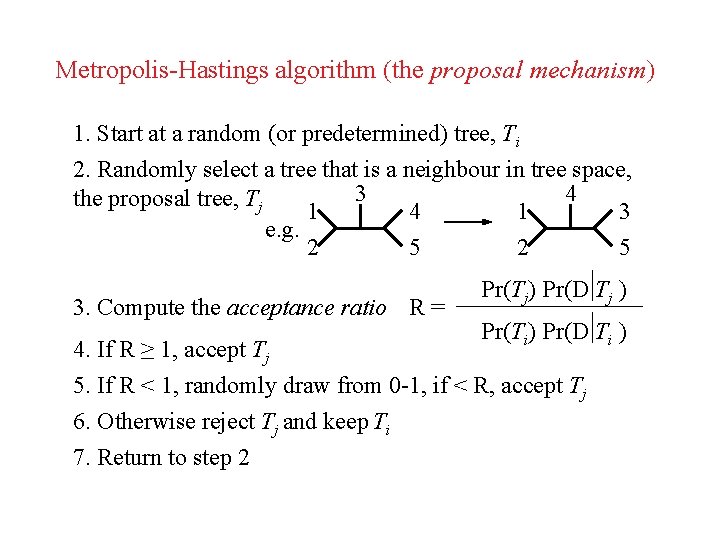

Metropolis-Hastings algorithm (the proposal mechanism) 1. Start at a random (or predetermined) tree, Ti 2. Randomly select a tree that is a neighbour in tree space, 3 4 the proposal tree, Tj 1 4 1 3 e. g. 2 5 3. Compute the acceptance ratio R = Pr(Tj) Pr(D Tj ) Pr(Ti) Pr(D Ti ) 4. If R ≥ 1, accept Tj 5. If R < 1, randomly draw from 0 -1, if < R, accept Tj 6. Otherwise reject Tj and keep Ti 7. Return to step 2

Useful properties of MCMC for Bayesian inference • Given an efficient proposal mechanism and sufficient generations, the MCMC with reach an equilibrium distribution • The problem of summing across all hypotheses cancels out in the acceptance ratio for Tj / Ti • The section of the MCMC that is “finding its way” towards the equilibrium distribution (the burnin) can be discarded - it is not a valid approximation for the posterior probability

Metropolis-coupled MCMC (MC 3) n chains, of which n-1 are “heated” such that they can more easily move across peaks and valleys in the landscape of trees. After all n chains have gone step a swap between randomly chosen chains is proposed (in much the same way as between generations). If accepted the two chains switch states. The cold chain (which could be stuck in a local optimum) can escape when a proposed swap with a hot chain is successful.

Sampling three simultaneous chains (Mr. Bayes 3. 0: Heulsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001) Generation 4100 4200 4300 4400 4500 4600 4700 4800 ----- chain 1 chain 2 chain 3 (-15395. 901) (-15395. 854) (-15381. 440) (-15375. 695) [-15374. 458] [-15358. 899] [-15350. 419] (-15369. 614) (-15376. 724) (-15377. 874) [-15376. 072] (-15369. 686) (-15372. 051) (-15366. 374) (-15366. 082) [-15368. 152] [-15367. 235] [-15368. 146] (-15368. 164) [-15369. 127] (-15370. 876) (-15365. 927) (-15366. 168) (-15369. 902) Proposing new trees along individual chains and swapping trees between chains (to more efficiently explore tree space)

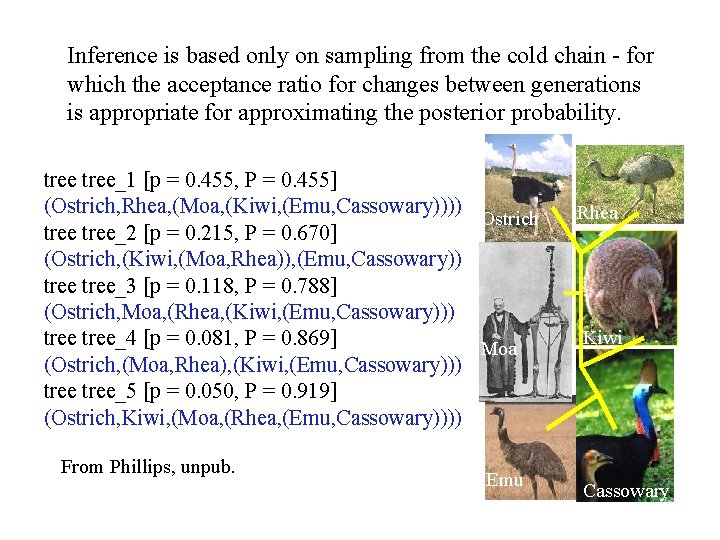

Inference is based only on sampling from the cold chain - for which the acceptance ratio for changes between generations is appropriate for approximating the posterior probability. tree_1 [p = 0. 455, P = 0. 455] (Ostrich, Rhea, (Moa, (Kiwi, (Emu, Cassowary)))) Ostrich tree_2 [p = 0. 215, P = 0. 670] (Ostrich, (Kiwi, (Moa, Rhea)), (Emu, Cassowary)) tree_3 [p = 0. 118, P = 0. 788] (Ostrich, Moa, (Rhea, (Kiwi, (Emu, Cassowary))) tree_4 [p = 0. 081, P = 0. 869] Moa (Ostrich, (Moa, Rhea), (Kiwi, (Emu, Cassowary))) tree_5 [p = 0. 050, P = 0. 919] (Ostrich, Kiwi, (Moa, (Rhea, (Emu, Cassowary)))) From Phillips, unpub. Emu Rhea Kiwi Cassowary

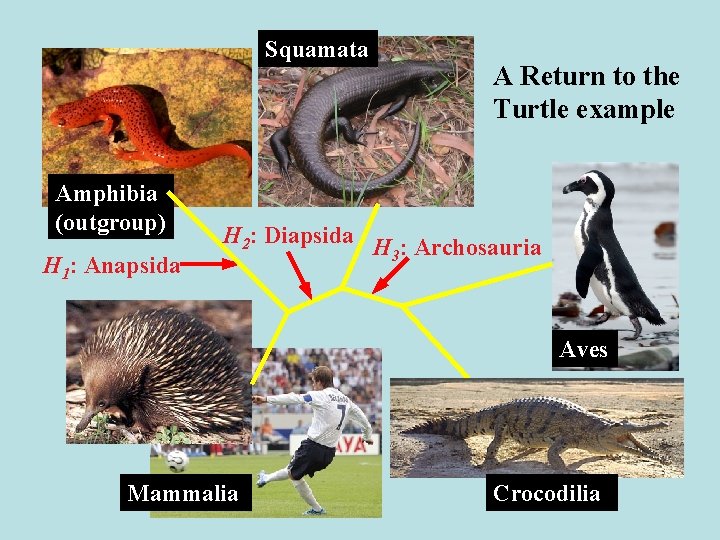

Squamata Amphibia (outgroup) H 1: Anapsida A Return to the Turtle example H 2: Diapsida H : Archosauria 3 Aves Mammalia Crocodilia

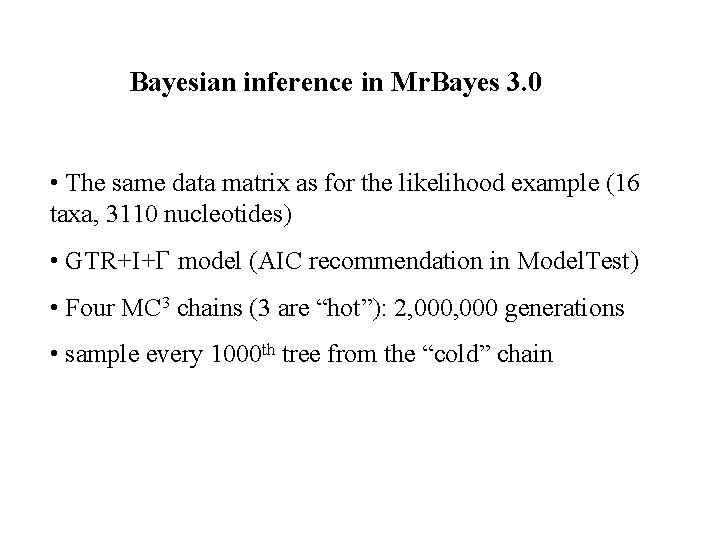

Bayesian inference in Mr. Bayes 3. 0 • The same data matrix as for the likelihood example (16 taxa, 3110 nucleotides) • GTR+I+ model (AIC recommendation in Model. Test) • Four MC 3 chains (3 are “hot”): 2, 000 generations • sample every 1000 th tree from the “cold” chain

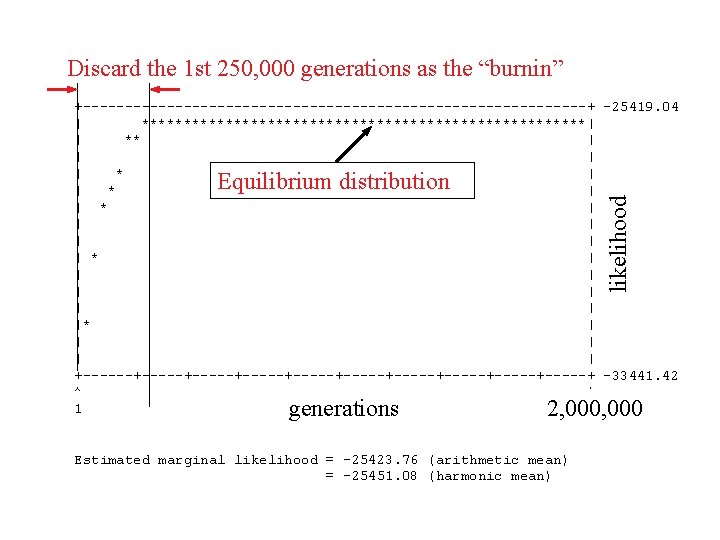

Discard the 1 st 250, 000 generations as the “burnin” +------------------------------+ -25419. 04 | ***************************| | ** | | * | | | |* | | | +------+-----+-----+-----+-----+ -33441. 42 ^ ^ 1 10000 likelihood Equilibrium distribution generations 2, 000 Estimated marginal likelihood = -25423. 76 (arithmetic mean) = -25451. 08 (harmonic mean)

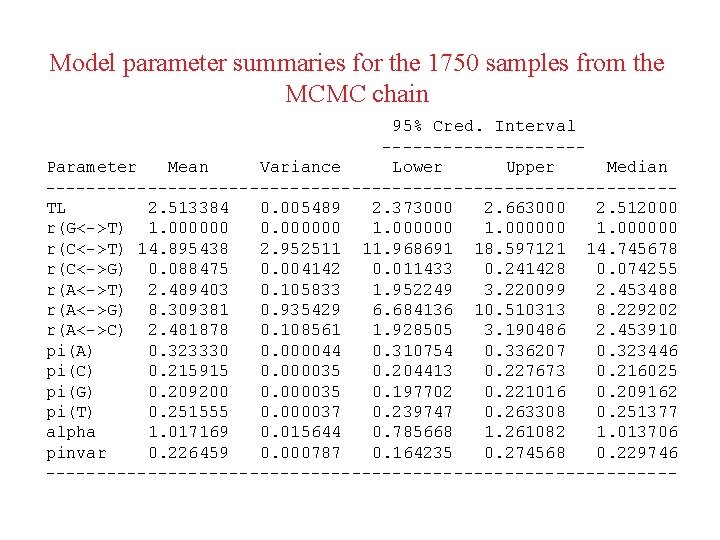

Model parameter summaries for the 1750 samples from the MCMC chain 95% Cred. Interval ----------Parameter Mean Variance Lower Upper Median -------------------------------TL 2. 513384 0. 005489 2. 373000 2. 663000 2. 512000 r(G<->T) 1. 000000 0. 000000 1. 000000 r(C<->T) 14. 895438 2. 952511 11. 968691 18. 597121 14. 745678 r(C<->G) 0. 088475 0. 004142 0. 011433 0. 241428 0. 074255 r(A<->T) 2. 489403 0. 105833 1. 952249 3. 220099 2. 453488 r(A<->G) 8. 309381 0. 935429 6. 684136 10. 510313 8. 229202 r(A<->C) 2. 481878 0. 108561 1. 928505 3. 190486 2. 453910 pi(A) 0. 323330 0. 000044 0. 310754 0. 336207 0. 323446 pi(C) 0. 215915 0. 000035 0. 204413 0. 227673 0. 216025 pi(G) 0. 209200 0. 000035 0. 197702 0. 221016 0. 209162 pi(T) 0. 251555 0. 000037 0. 239747 0. 263308 0. 251377 alpha 1. 017169 0. 015644 0. 785668 1. 261082 1. 013706 pinvar 0. 226459 0. 000787 0. 164235 0. 274568 0. 229746 -------------------------------

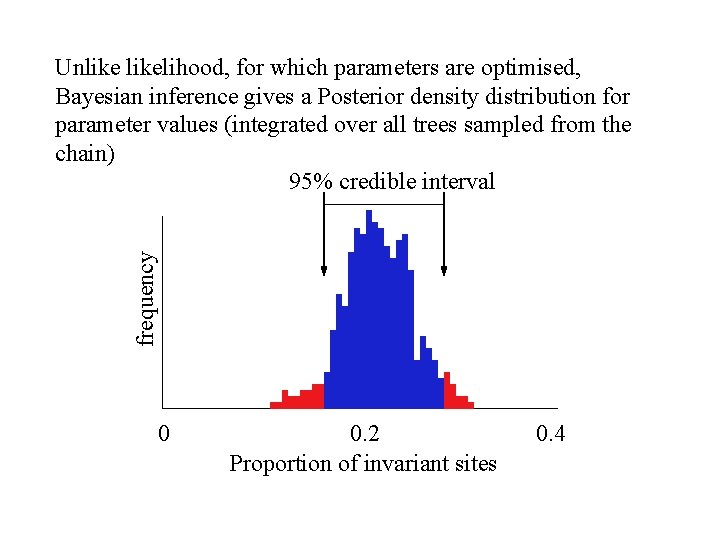

frequency Unlikelihood, for which parameters are optimised, Bayesian inference gives a Posterior density distribution for parameter values (integrated over all trees sampled from the chain) 95% credible interval 0 0. 2 Proportion of invariant sites 0. 4

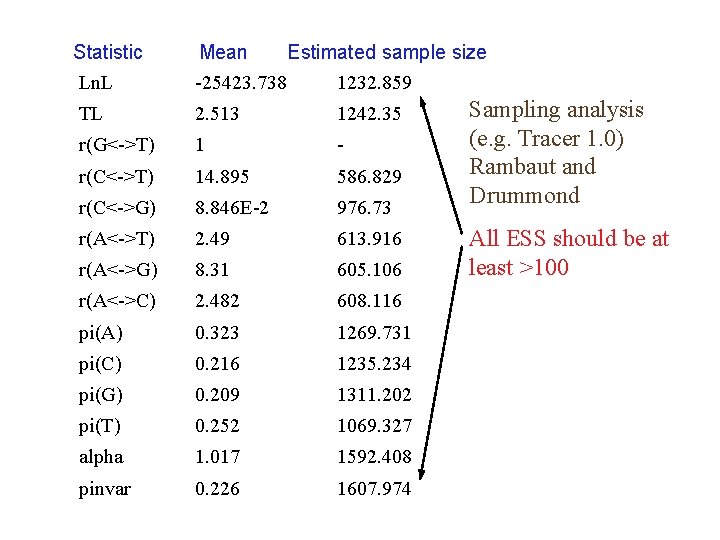

Statistic Ln. L Mean Estimated sample size -25423. 738 1232. 859 TL 2. 513 1242. 35 r(G<->T) 1 - r(C<->T) 14. 895 586. 829 r(C<->G) 8. 846 E-2 976. 73 r(A<->T) 2. 49 613. 916 r(A<->G) 8. 31 605. 106 r(A<->C) 2. 482 608. 116 pi(A) 0. 323 1269. 731 pi(C) 0. 216 1235. 234 pi(G) 0. 209 1311. 202 pi(T) 0. 252 1069. 327 alpha 1. 017 1592. 408 pinvar 0. 226 1607. 974 Sampling analysis (e. g. Tracer 1. 0) Rambaut and Drummond All ESS should be at least >100

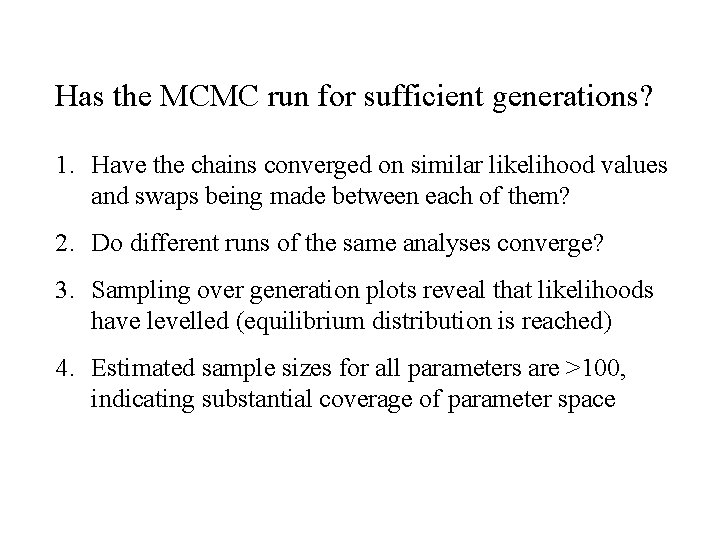

Has the MCMC run for sufficient generations? 1. Have the chains converged on similar likelihood values and swaps being made between each of them? 2. Do different runs of the same analyses converge? 3. Sampling over generation plots reveal that likelihoods have levelled (equilibrium distribution is reached) 4. Estimated sample sizes for all parameters are >100, indicating substantial coverage of parameter space

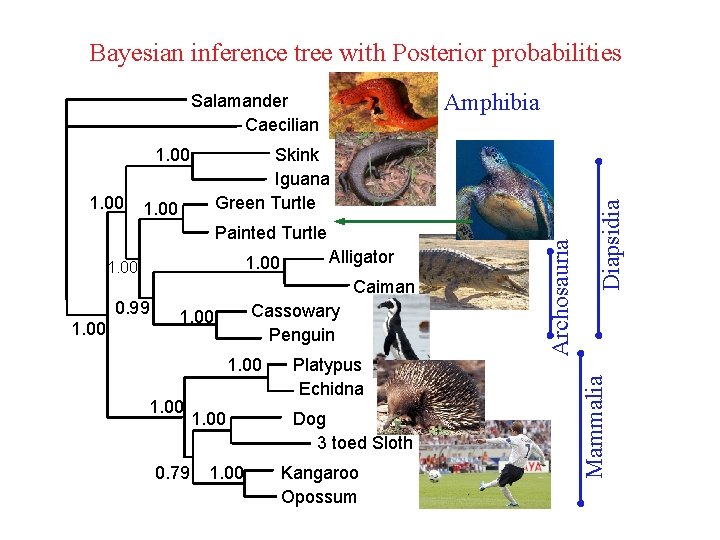

Bayesian inference tree with Posterior probabilities 1. 00 Painted Turtle 1. 00 Alligator Caiman 0. 99 1. 00 Cassowary Penguin 1. 00 0. 79 1. 00 Platypus Echidna Dog 3 toed Sloth Kangaroo Opossum Mammalia 1. 00 Skink Iguana Green Turtle Archosauria 1. 00 Diapsidia Amphibia Salamander Caecilian

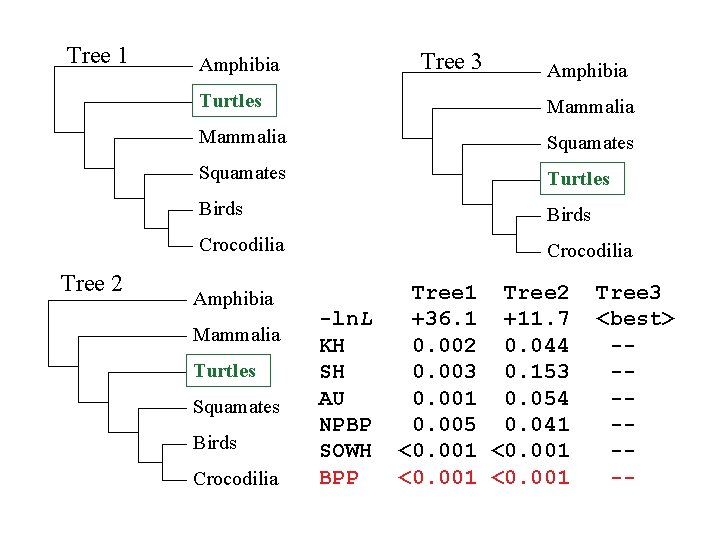

Tree 1 Tree 2 Tree 3 Amphibia Turtles Mammalia Squamates Turtles Birds Crocodilia Amphibia Mammalia Turtles Squamates Birds Crocodilia -ln. L KH SH AU NPBP SOWH BPP Tree 1 Tree 2 +36. 1 +11. 7 0. 002 0. 044 0. 003 0. 153 0. 001 0. 054 0. 005 0. 041 <0. 001 Tree 3 <best> -------

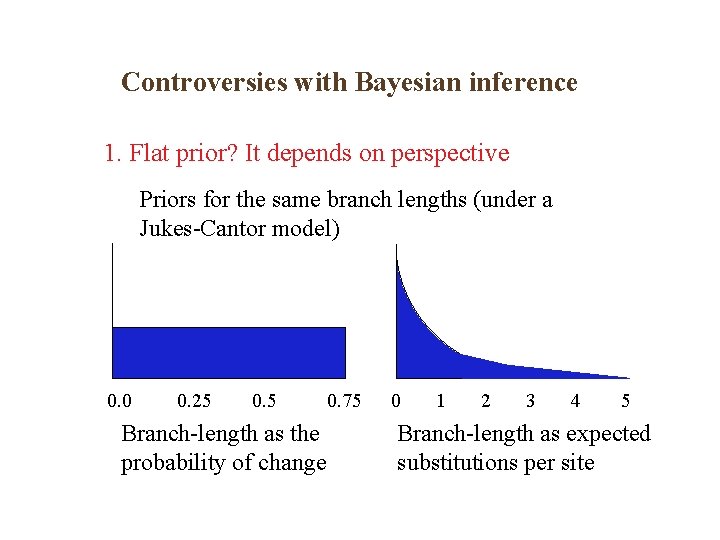

Controversies with Bayesian inference 1. Flat prior? It depends on perspective Priors for the same branch lengths (under a Jukes-Cantor model) 0. 0 0. 25 0. 5 Branch-length as the probability of change 0. 75 0 1 2 3 4 5 Branch-length as expected substitutions per site

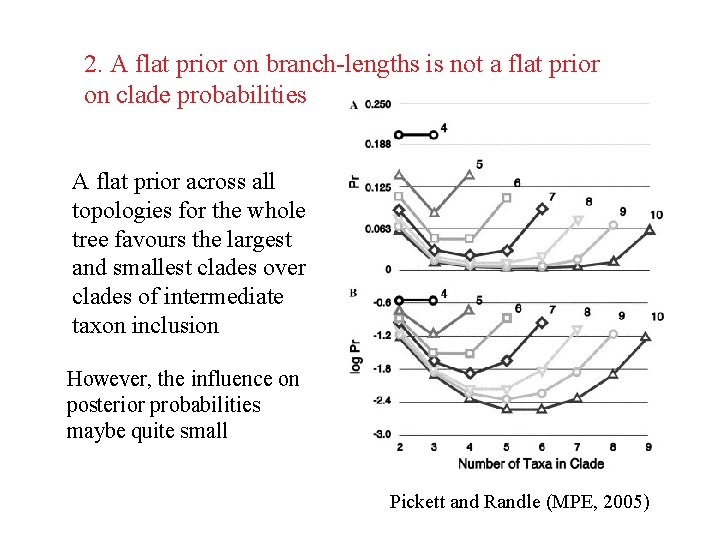

2. A flat prior on branch-lengths is not a flat prior on clade probabilities A flat prior across all topologies for the whole tree favours the largest and smallest clades over clades of intermediate taxon inclusion However, the influence on posterior probabilities maybe quite small Pickett and Randle (MPE, 2005)

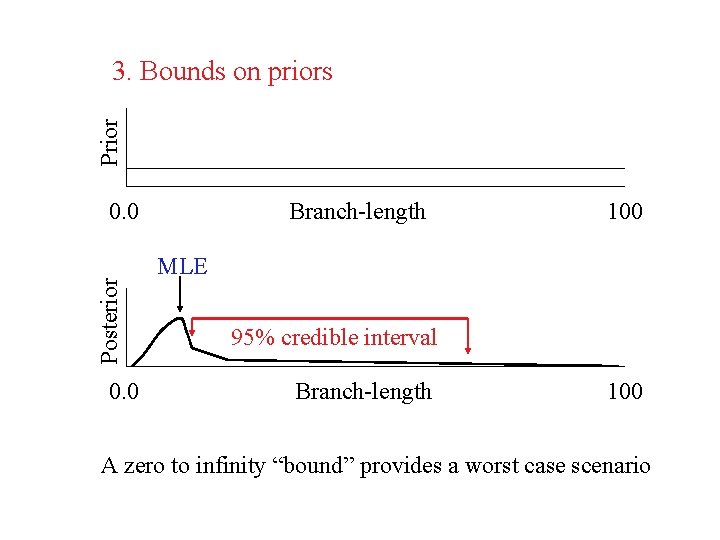

Prior 3. Bounds on priors Posterior 0. 0 Branch-length 100 MLE 95% credible interval Branch-length 100 A zero to infinity “bound” provides a worst case scenario

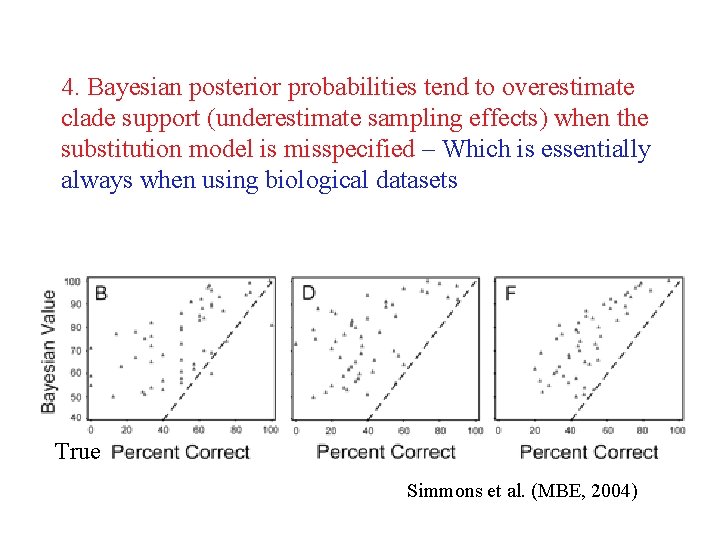

4. Bayesian posterior probabilities tend to overestimate clade support (underestimate sampling effects) when the substitution model is misspecified – Which is essentially always when using biological datasets True Simmons et al. (MBE, 2004)

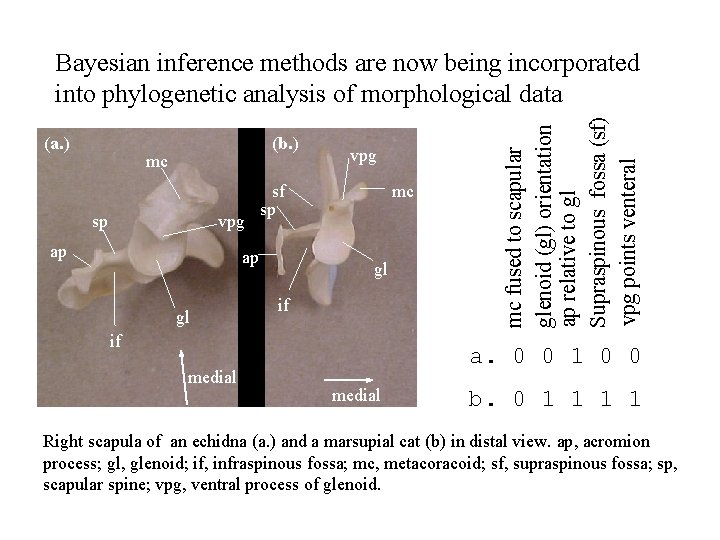

(a. ) (b. ) mc sp vpg ap sf sp ap gl vpg mc gl if if medial mc fused to scapular glenoid (gl) orientation ap relative to gl Supraspinous fossa (sf) vpg points venteral Bayesian inference methods are now being incorporated into phylogenetic analysis of morphological data a. 0 0 1 0 0 medial b. 0 1 1 Right scapula of an echidna (a. ) and a marsupial cat (b) in distal view. ap, acromion process; gl, glenoid; if, infraspinous fossa; mc, metacoracoid; sf, supraspinous fossa; sp, scapular spine; vpg, ventral process of glenoid.

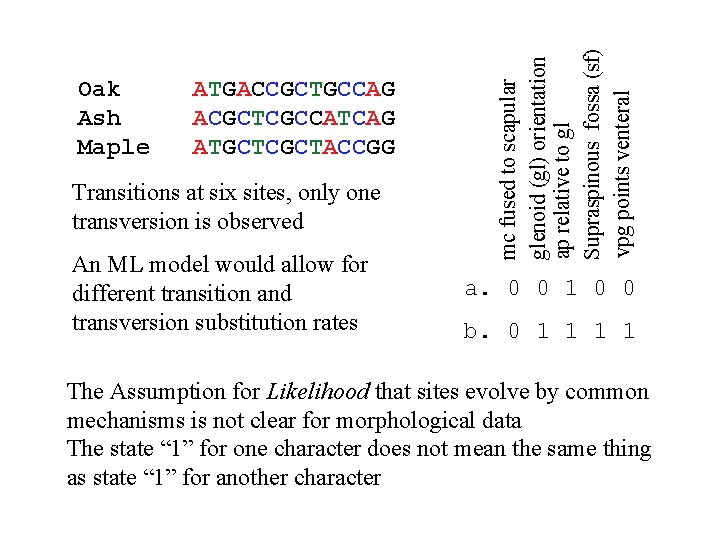

ATGACCGCTGCCAG ACGCTCGCCATCAG ATGCTCGCTACCGG Transitions at six sites, only one transversion is observed An ML model would allow for different transition and transversion substitution rates mc fused to scapular glenoid (gl) orientation ap relative to gl Supraspinous fossa (sf) vpg points venteral Oak Ash Maple a. 0 0 1 0 0 b. 0 1 1 The Assumption for Likelihood that sites evolve by common mechanisms is not clear for morphological data The state “ 1” for one character does not mean the same thing as state “ 1” for another character

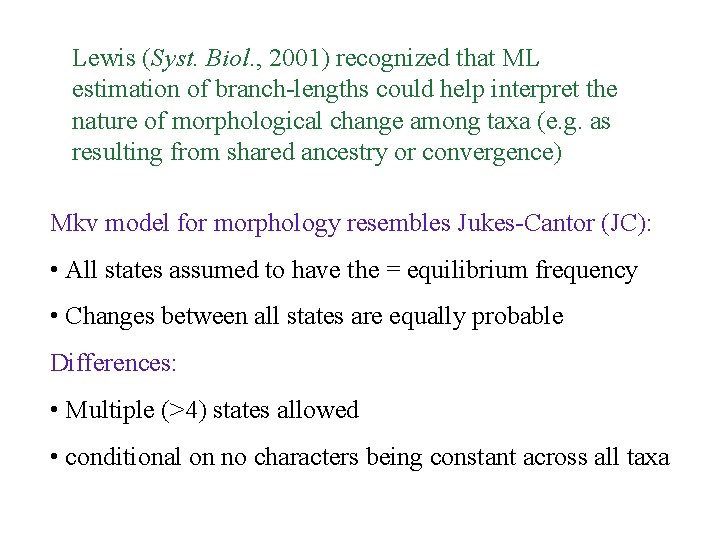

Lewis (Syst. Biol. , 2001) recognized that ML estimation of branch-lengths could help interpret the nature of morphological change among taxa (e. g. as resulting from shared ancestry or convergence) Mkv model for morphology resembles Jukes-Cantor (JC): • All states assumed to have the = equilibrium frequency • Changes between all states are equally probable Differences: • Multiple (>4) states allowed • conditional on no characters being constant across all taxa

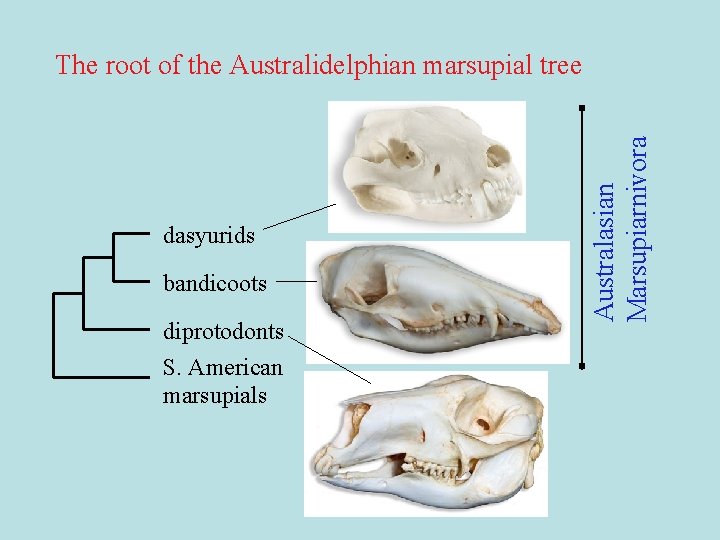

dasyurids bandicoots diprotodonts S. American marsupials Australasian Marsupiarnivora The root of the Australidelphian marsupial tree

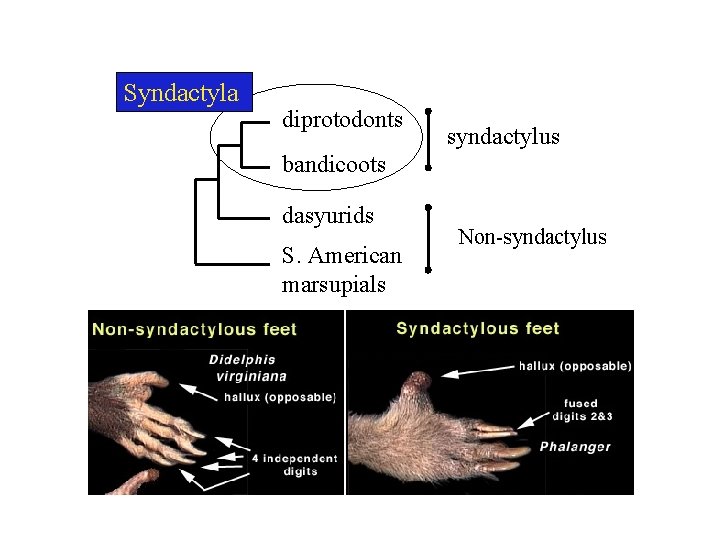

Syndactyla diprotodonts syndactylus bandicoots dasyurids S. American marsupials Non-syndactylus

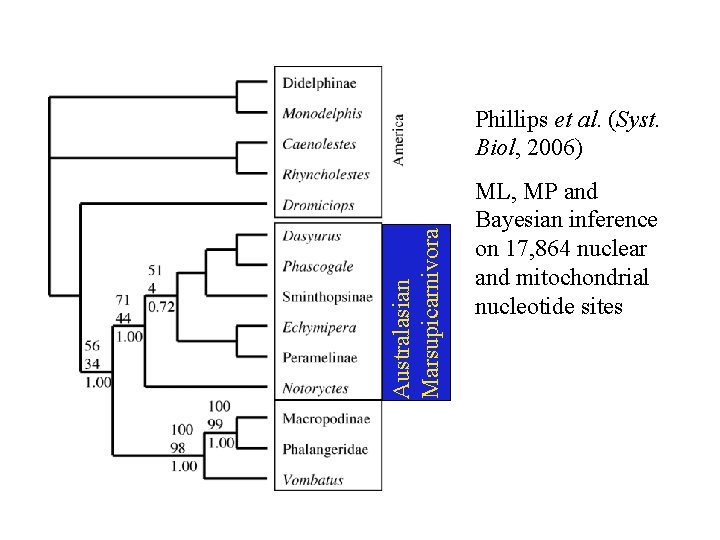

Australasian Marsupicarnivora Phillips et al. (Syst. Biol, 2006) ML, MP and Bayesian inference on 17, 864 nuclear and mitochondrial nucleotide sites

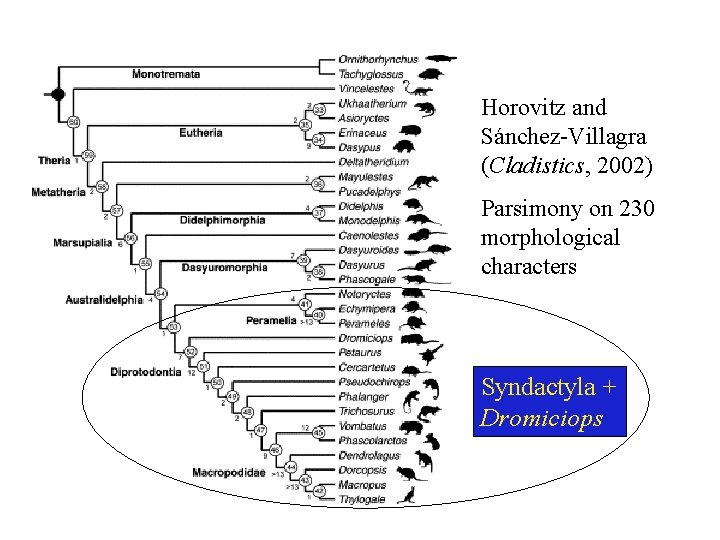

Horovitz and Sánchez-Villagra (Cladistics, 2002) Parsimony on 230 morphological characters Syndactyla + Dromiciops

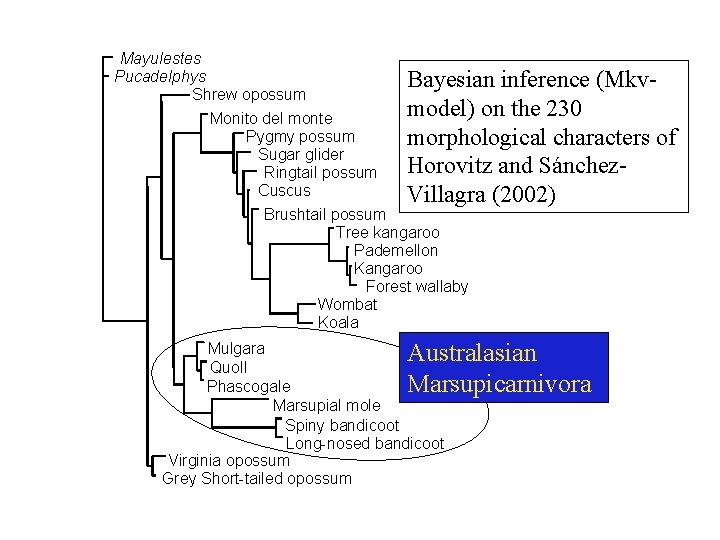

Mayulestes Pucadelphys Bayesian inference (Mkv. Shrew opossum model) on the 230 Monito del monte Pygmy possum morphological characters of Sugar glider Horovitz and Sánchez. Ringtail possum Cuscus Villagra (2002) Brushtail possum Tree kangaroo Pademellon Kangaroo Forest wallaby Wombat Koala Australasian Marsupicarnivora Mulgara Quoll Phascogale Marsupial mole Spiny bandicoot Long-nosed bandicoot Virginia opossum Grey Short-tailed opossum

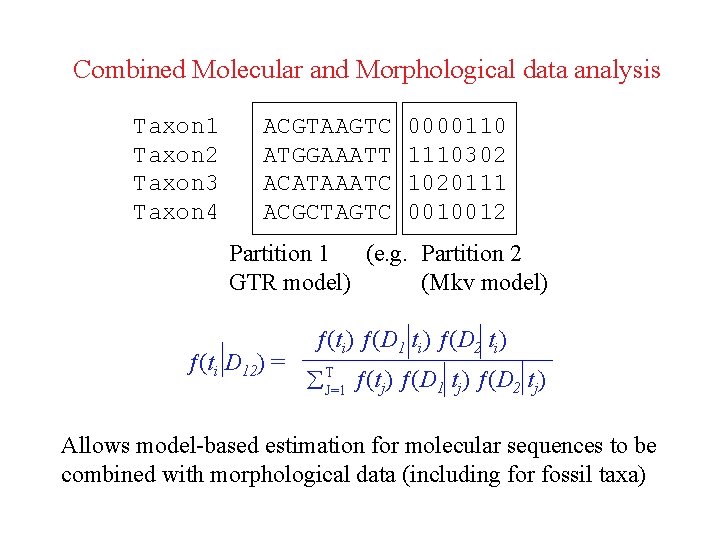

Combined Molecular and Morphological data analysis Taxon 1 Taxon 2 Taxon 3 Taxon 4 ACGTAAGTC ATGGAAATT ACATAAATC ACGCTAGTC 0000110 1110302 1020111 0010012 Partition 1 (e. g. Partition 2 GTR model) (Mkv model) (ti D 12) = (ti) (D 1 ti) (D 2 ti) TJ=1 (tj) (D 1 tj) (D 2 tj) Allows model-based estimation for molecular sequences to be combined with morphological data (including for fossil taxa)

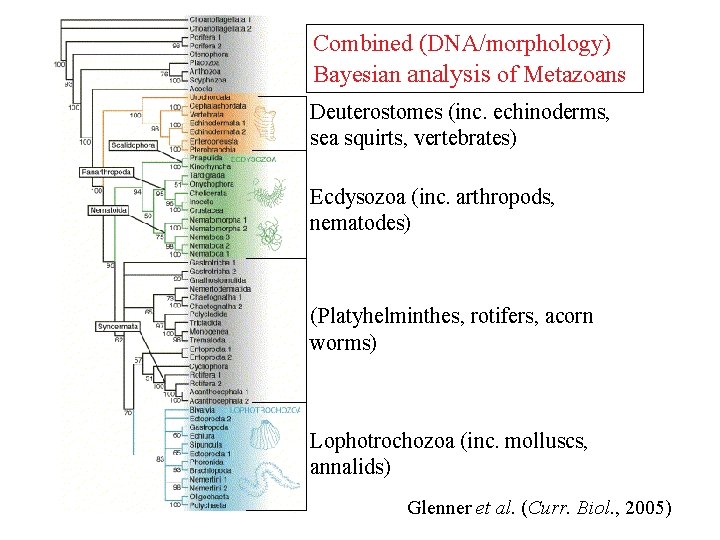

Combined (DNA/morphology) Bayesian analysis of Metazoans Deuterostomes (inc. echinoderms, sea squirts, vertebrates) Ecdysozoa (inc. arthropods, nematodes) (Platyhelminthes, rotifers, acorn worms) Lophotrochozoa (inc. molluscs, annalids) Glenner et al. (Curr. Biol. , 2005)

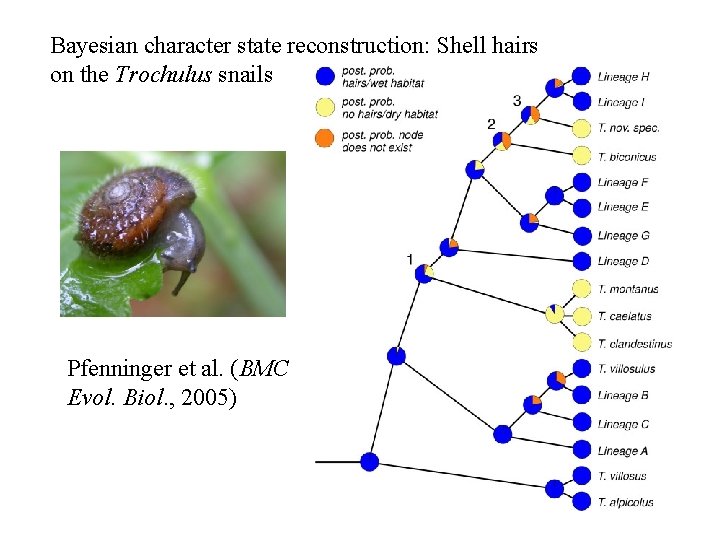

Bayesian character state reconstruction: Shell hairs on the Trochulus snails Pfenninger et al. (BMC Evol. Biol. , 2005)

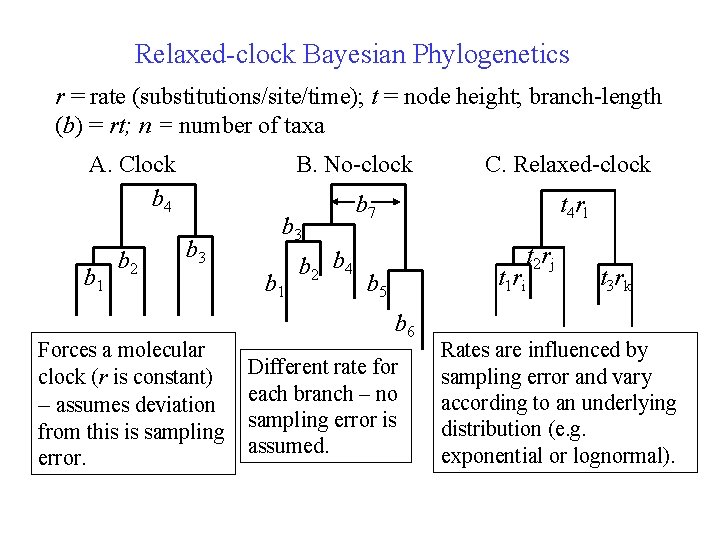

Relaxed-clock Bayesian Phylogenetics r = rate (substitutions/site/time); t = node height; branch-length (b) = rt; n = number of taxa A. Clock b 4 b 1 b 2 B. No-clock b 3 Forces a molecular clock (r is constant) – assumes deviation from this is sampling error. b 3 b 1 b 2 b 4 C. Relaxed-clock b 7 t 4 rl t 2 rj t 1 ri b 5 b 6 Different rate for each branch – no sampling error is assumed. t 3 rk Rates are influenced by sampling error and vary according to an underlying distribution (e. g. exponential or lognormal).

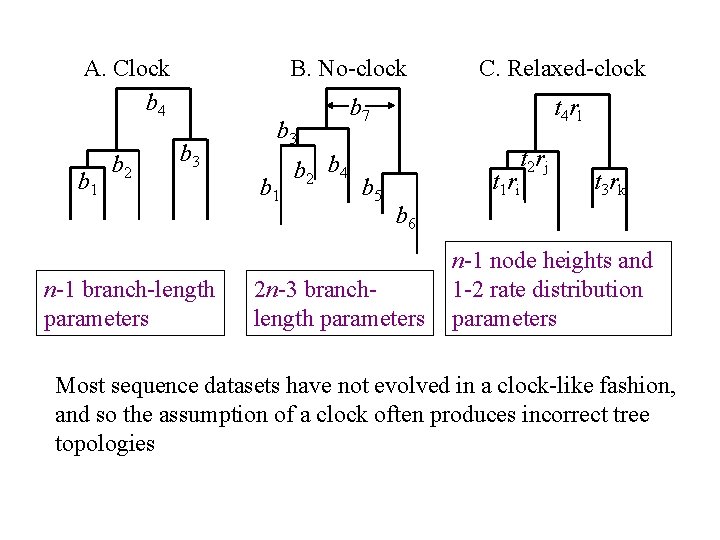

A. Clock b 4 b 1 b 2 B. No-clock b 3 n-1 branch-length parameters b 3 b 1 b 2 b 4 C. Relaxed-clock b 7 b 5 t 4 rl t 2 rj t 1 ri t 3 rk b 6 2 n-3 branchlength parameters n-1 node heights and 1 -2 rate distribution parameters Most sequence datasets have not evolved in a clock-like fashion, and so the assumption of a clock often produces incorrect tree topologies

Relaxed-clocks : the holy grail of phylogenetics? • By allowing for the influence of sampling error, relaxedclock models can more accurately infer underlying substitution rates and hence provide greater phylogenetic accuracy. • By estimating fewer branch-length parameters, less variance will tend to be associated with relaxed-clock model estimates, thus providing for greater phylogenetic precision than no-clock models • However, we need to know how well fitting the rate distribution models are

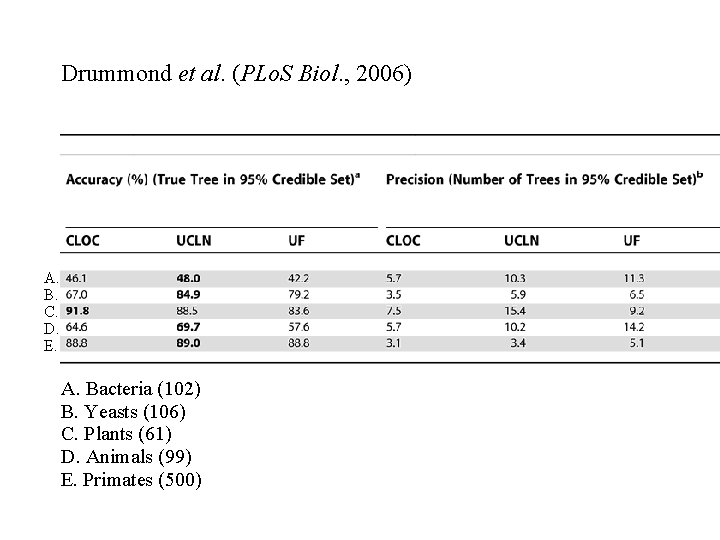

Drummond et al. (PLo. S Biol. , 2006) A. B. C. D. E. A. Bacteria (102) B. Yeasts (106) C. Plants (61) D. Animals (99) E. Primates (500)

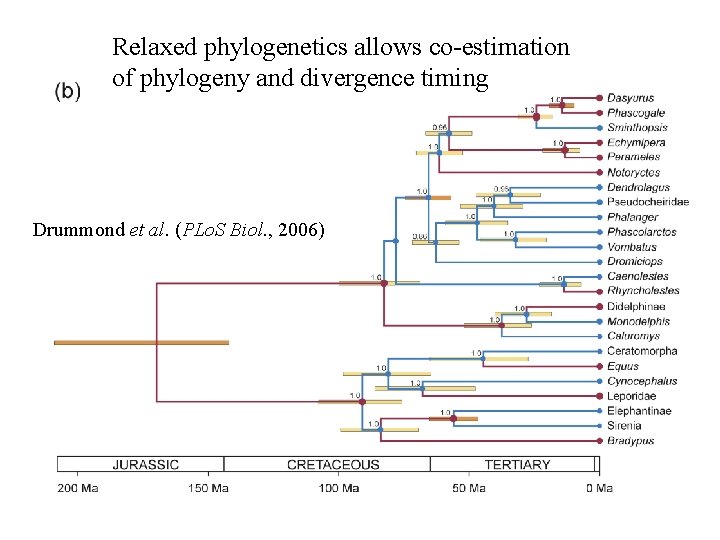

Relaxed phylogenetics allows co-estimation of phylogeny and divergence timing Drummond et al. (PLo. S Biol. , 2006)

- Slides: 42