Lecture 22 LowLevel Programming in C CS 201

![Manipulating Addresses char s[6]; s[0] = ‘h’; expr 1[expr 2] in C is just Manipulating Addresses char s[6]; s[0] = ‘h’; expr 1[expr 2] in C is just](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/bf85f32215cf64673ce7455716f67efa/image-25.jpg)

![Obfuscating C char s[6]; *s = ‘h’; *(s + 1) = ‘e’; 2[s] = Obfuscating C char s[6]; *s = ‘h’; *(s + 1) = ‘e’; 2[s] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/bf85f32215cf64673ce7455716f67efa/image-26.jpg)

- Slides: 41

Lecture 22: Low-Level Programming in C CS 201 j: Engineering Software University of Virginia 20 November 2003 Computer Science CS 201 J Fall 2003 David Evans http: //www. cs. virginia. edu/evans

Menu • PS 5 • C Programming Language • Pointers in C – Pointer Arithmetic • Type checking in C • Why is garbage collection hard in C? 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 2

PS 5 • Will return in section tomorrow • Some very impressive projects! – Will be posted on the course web site soon – Many people demonstrated ability to figure out complicated new things on their own (not a requirement for PS 5) • Stapling penalty for PS 6 will be 25 points 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 3

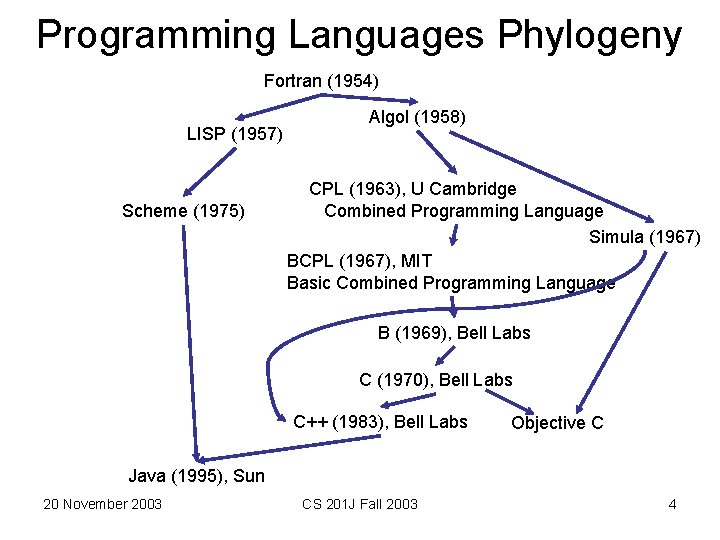

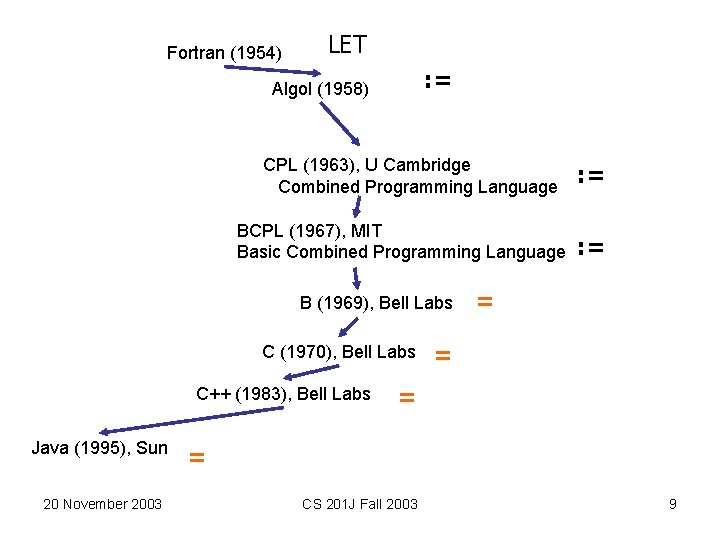

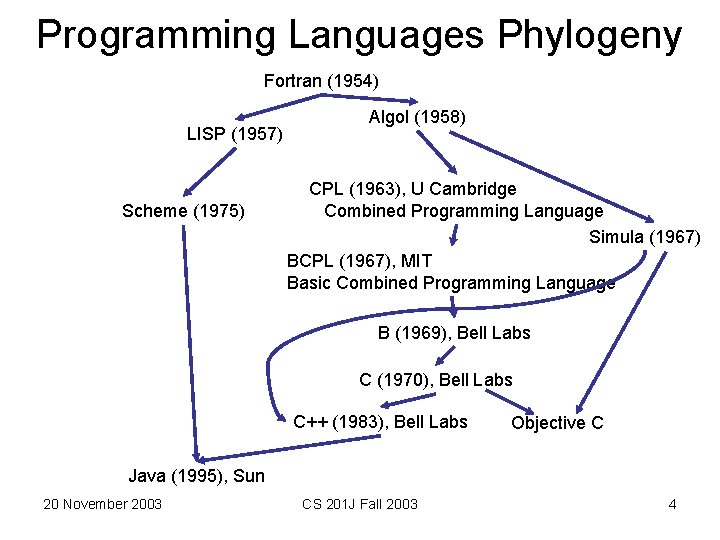

Programming Languages Phylogeny Fortran (1954) LISP (1957) Scheme (1975) Algol (1958) CPL (1963), U Cambridge Combined Programming Language Simula (1967) BCPL (1967), MIT Basic Combined Programming Language B (1969), Bell Labs C (1970), Bell Labs C++ (1983), Bell Labs Objective C Java (1995), Sun 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 4

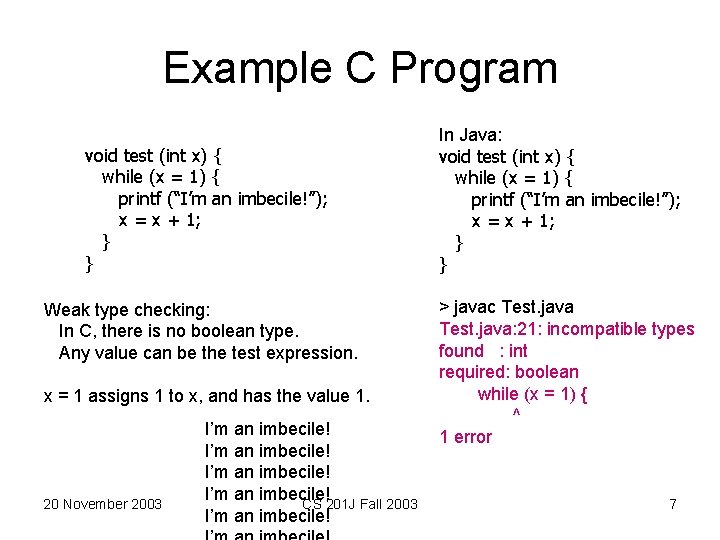

C Programming Language • Developed to build Unix operating system • Main design considerations: – Compiler size: needed to run on PDP-11 with 24 KB of memory (Algol 60 was too big to fit) – Code size: needed to implement the whole OS and applications with little memory – Performance – Portability • Little (if any consideration): – Security, robustness, maintainability 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 5

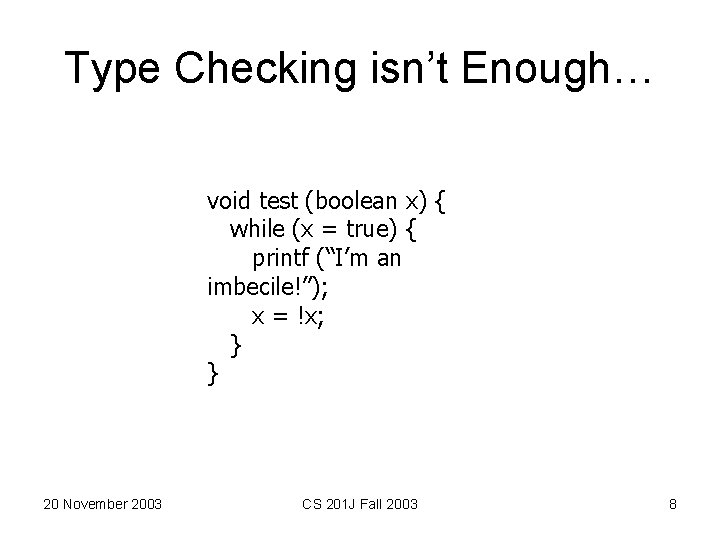

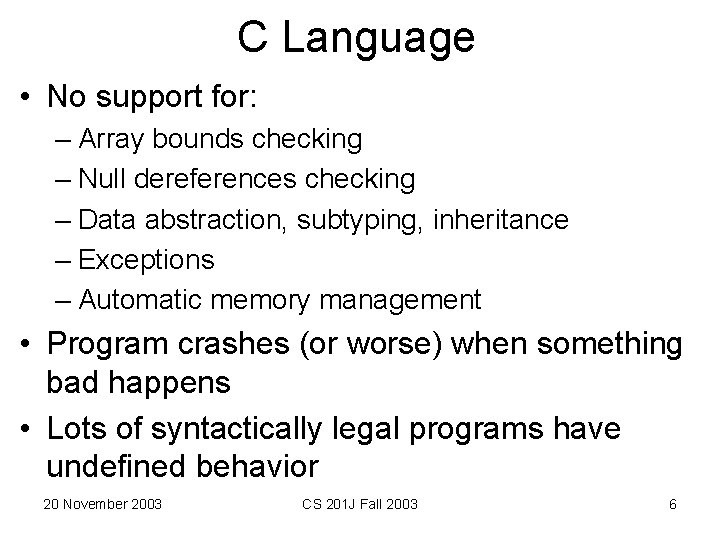

C Language • No support for: – Array bounds checking – Null dereferences checking – Data abstraction, subtyping, inheritance – Exceptions – Automatic memory management • Program crashes (or worse) when something bad happens • Lots of syntactically legal programs have undefined behavior 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 6

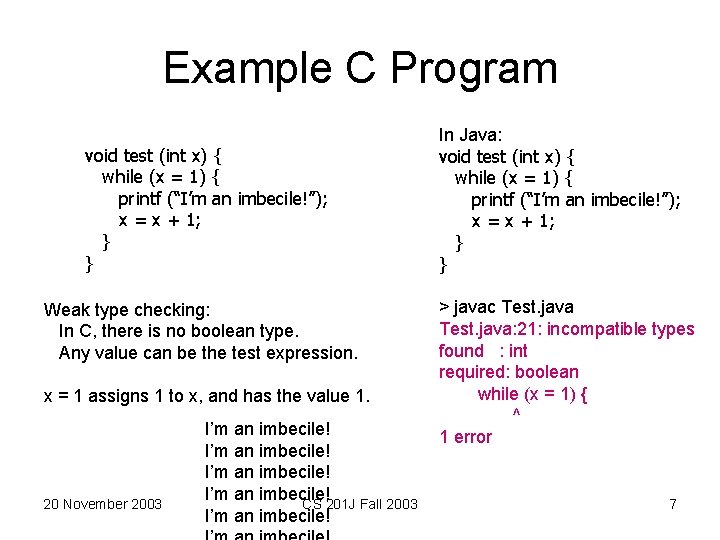

Example C Program void test (int x) { while (x = 1) { printf (“I’m an imbecile!”); x = x + 1; } } Weak type checking: In C, there is no boolean type. Any value can be the test expression. x = 1 assigns 1 to x, and has the value 1. 20 November 2003 I’m an imbecile! CS 201 J Fall 2003 I’m an imbecile! In Java: void test (int x) { while (x = 1) { printf (“I’m an imbecile!”); x = x + 1; } } > javac Test. java: 21: incompatible types found : int required: boolean while (x = 1) { ^ 1 error 7

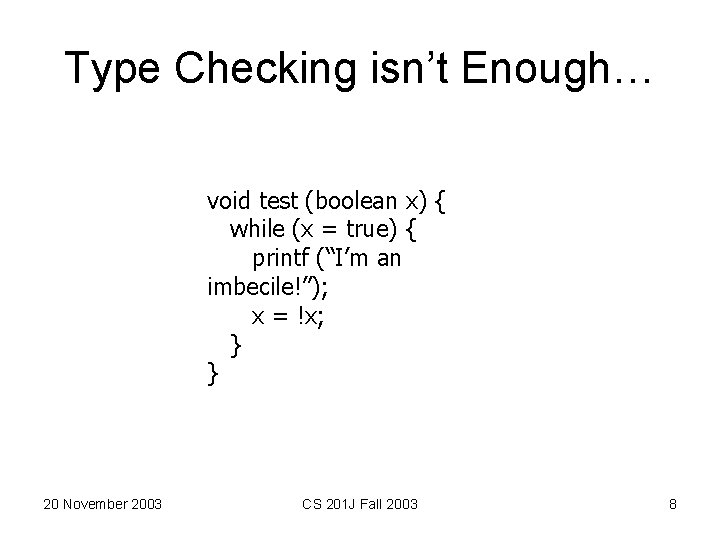

Type Checking isn’t Enough… void test (boolean x) { while (x = true) { printf (“I’m an imbecile!”); x = !x; } } 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 8

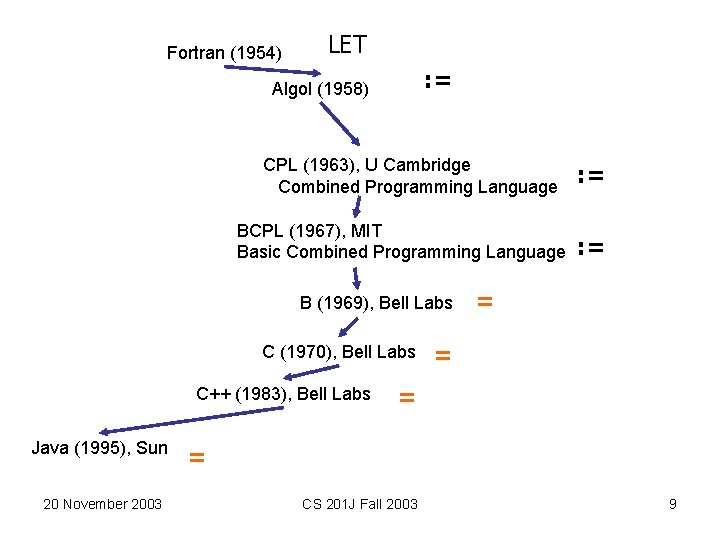

Fortran (1954) LET : = Algol (1958) CPL (1963), U Cambridge Combined Programming Language BCPL (1967), MIT Basic Combined Programming Language B (1969), Bell Labs C (1970), Bell Labs C++ (1983), Bell Labs Java (1995), Sun 20 November 2003 : = = = CS 201 J Fall 2003 9

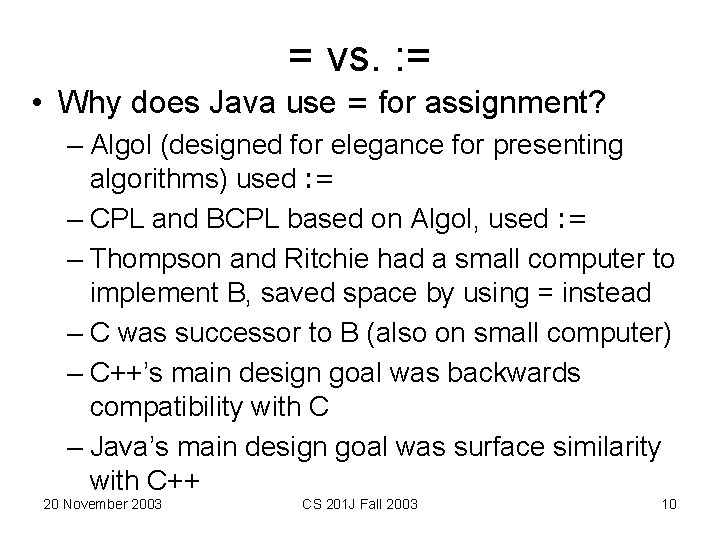

= vs. : = • Why does Java use = for assignment? – Algol (designed for elegance for presenting algorithms) used : = – CPL and BCPL based on Algol, used : = – Thompson and Ritchie had a small computer to implement B, saved space by using = instead – C was successor to B (also on small computer) – C++’s main design goal was backwards compatibility with C – Java’s main design goal was surface similarity with C++ 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 10

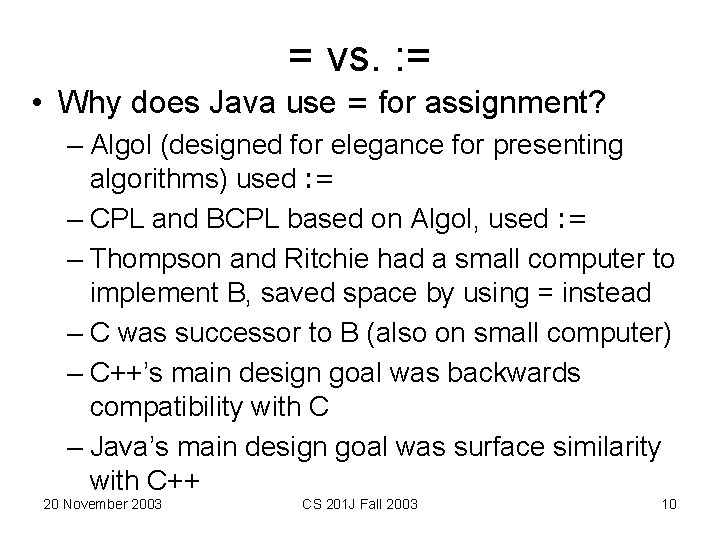

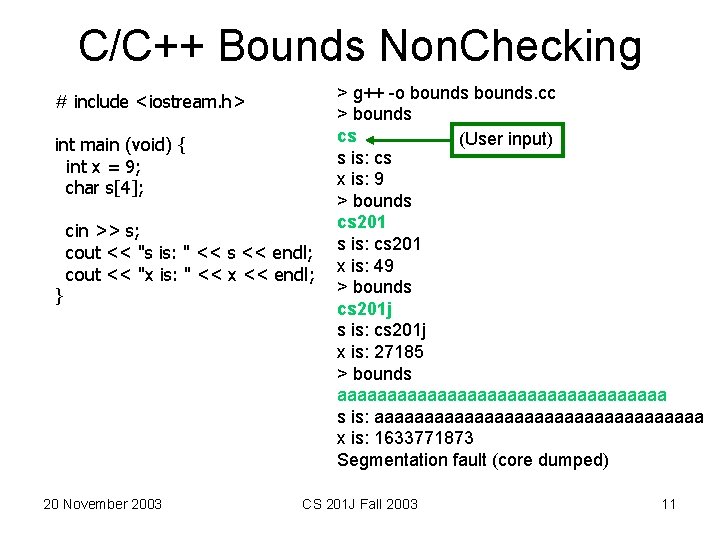

C/C++ Bounds Non. Checking # include <iostream. h> int main (void) { int x = 9; char s[4]; } cin >> s; cout << "s is: " << s << endl; cout << "x is: " << x << endl; 20 November 2003 > g++ -o bounds. cc > bounds cs (User input) s is: cs x is: 9 > bounds cs 201 s is: cs 201 x is: 49 > bounds cs 201 j s is: cs 201 j x is: 27185 > bounds aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa s is: aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa x is: 1633771873 Segmentation fault (core dumped) CS 201 J Fall 2003 11

So, why would anyone use C today? 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 12

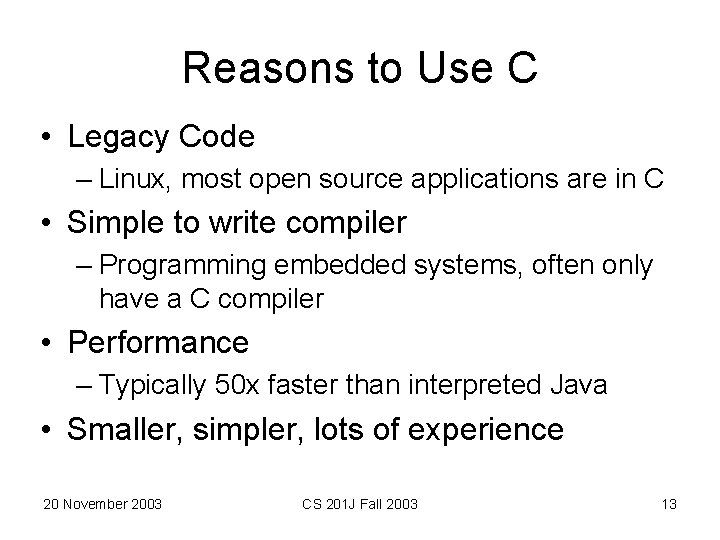

Reasons to Use C • Legacy Code – Linux, most open source applications are in C • Simple to write compiler – Programming embedded systems, often only have a C compiler • Performance – Typically 50 x faster than interpreted Java • Smaller, simpler, lots of experience 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 13

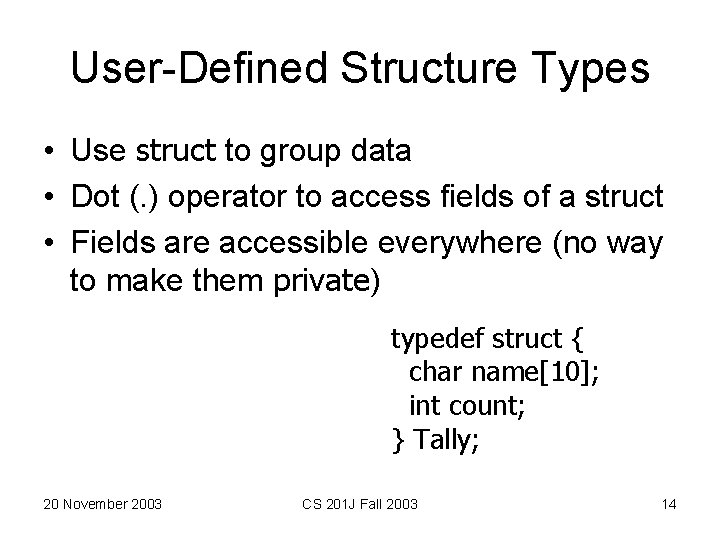

User-Defined Structure Types • Use struct to group data • Dot (. ) operator to access fields of a struct • Fields are accessible everywhere (no way to make them private) typedef struct { char name[10]; int count; } Tally; 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 14

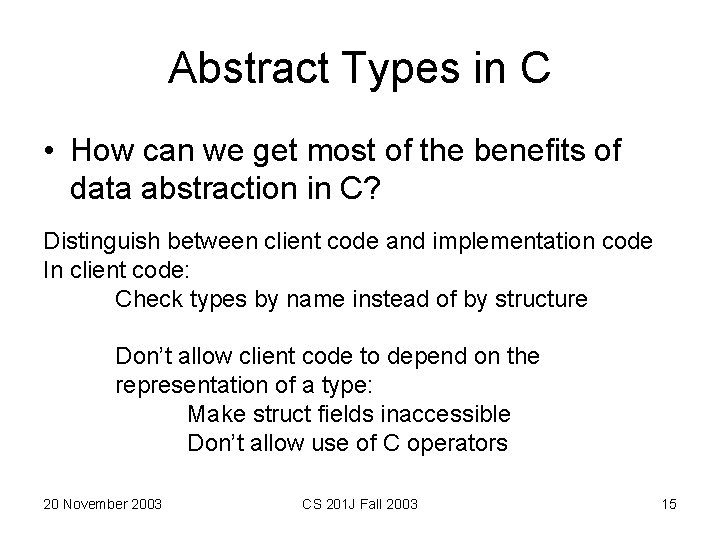

Abstract Types in C • How can we get most of the benefits of data abstraction in C? Distinguish between client code and implementation code In client code: Check types by name instead of by structure Don’t allow client code to depend on the representation of a type: Make struct fields inaccessible Don’t allow use of C operators 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 15

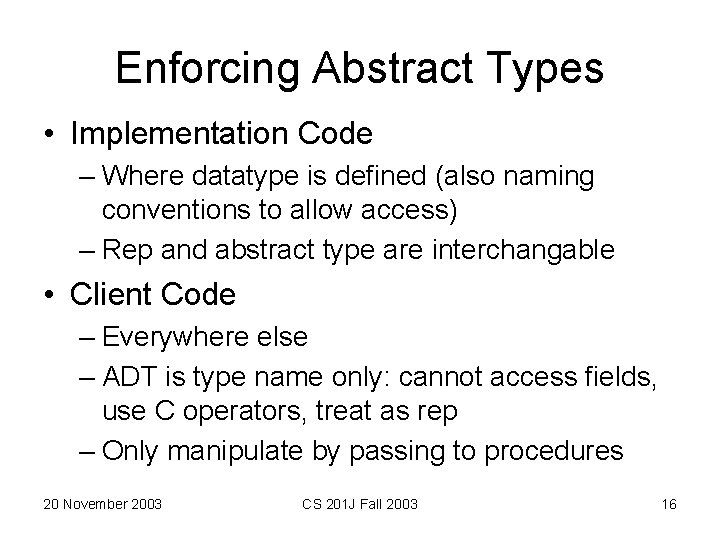

Enforcing Abstract Types • Implementation Code – Where datatype is defined (also naming conventions to allow access) – Rep and abstract type are interchangable • Client Code – Everywhere else – ADT is type name only: cannot access fields, use C operators, treat as rep – Only manipulate by passing to procedures 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 16

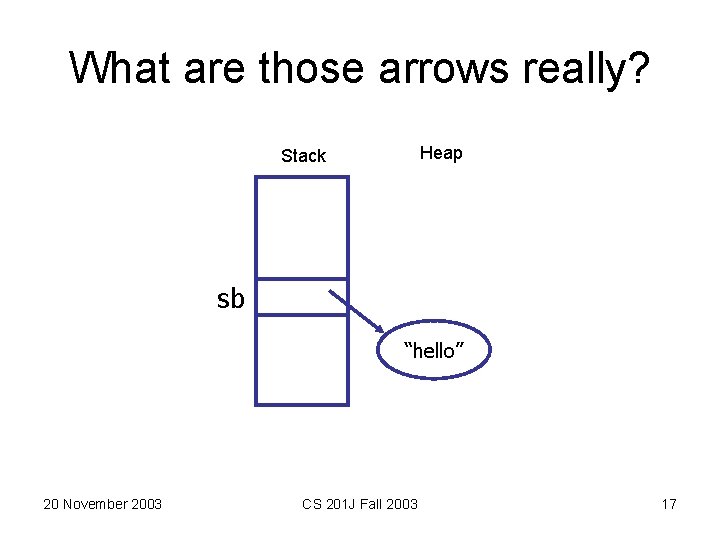

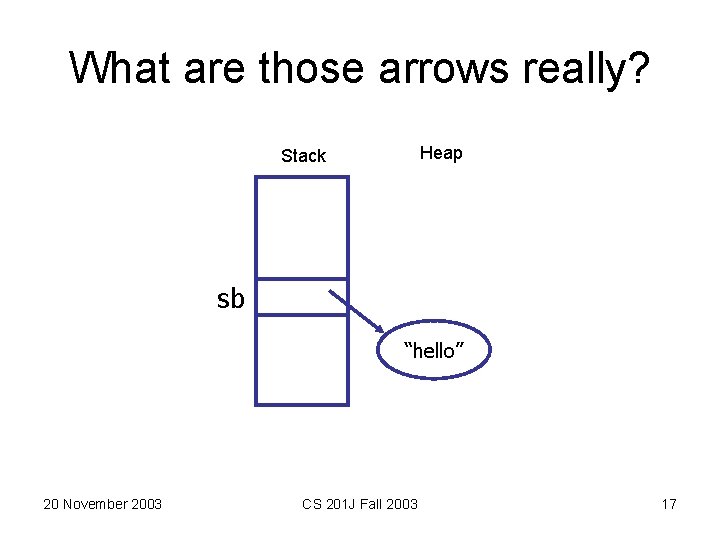

What are those arrows really? Heap Stack sb “hello” 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 17

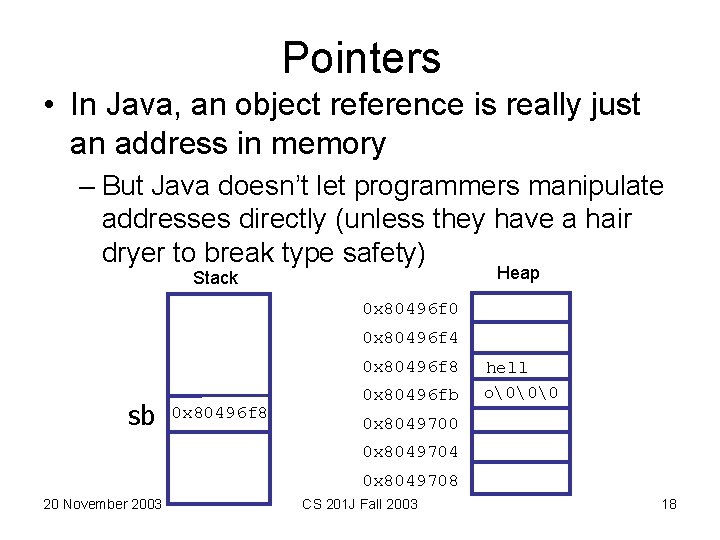

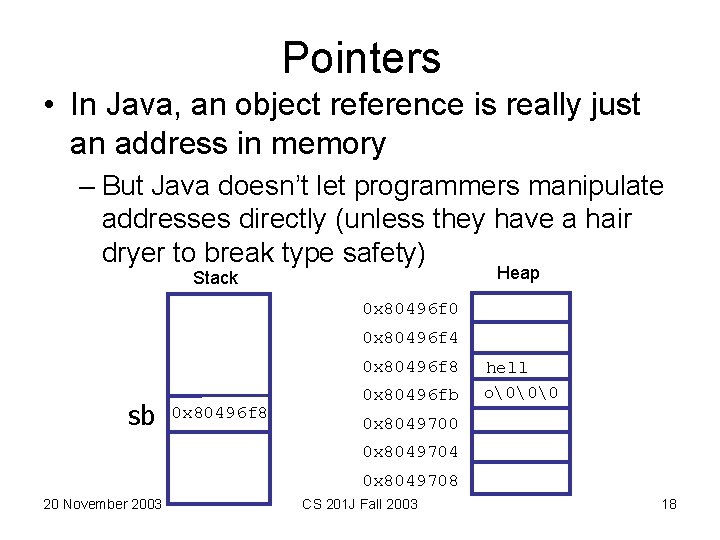

Pointers • In Java, an object reference is really just an address in memory – But Java doesn’t let programmers manipulate addresses directly (unless they have a hair dryer to break type safety) Heap Stack 0 x 80496 f 0 0 x 80496 f 4 0 x 80496 f 8 sb 0 x 80496 f 8 0 x 80496 fb hell o��� 0 x 8049704 0 x 8049708 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 18

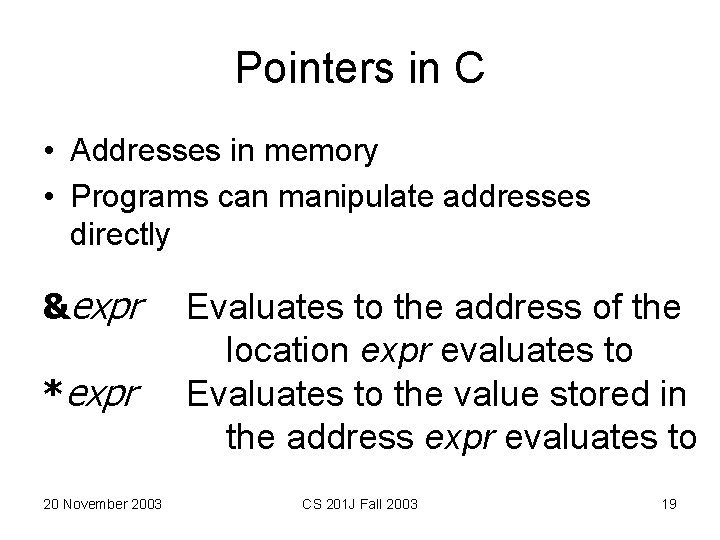

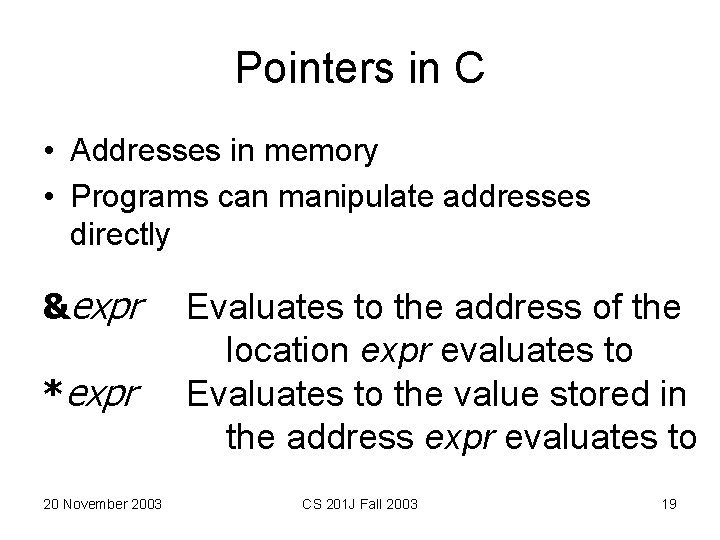

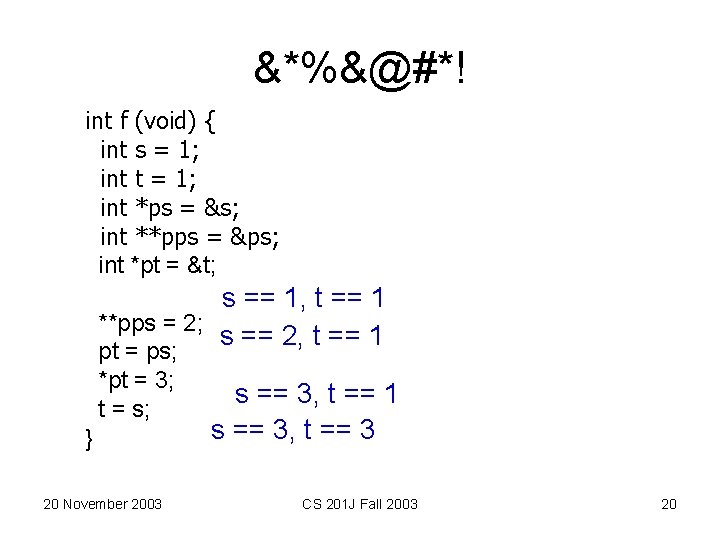

Pointers in C • Addresses in memory • Programs can manipulate addresses directly &expr *expr 20 November 2003 Evaluates to the address of the location expr evaluates to Evaluates to the value stored in the address expr evaluates to CS 201 J Fall 2003 19

&*%&@#*! int f (void) { int s = 1; int t = 1; int *ps = &s; int **pps = &ps; int *pt = &t; s == 1, t == 1 **pps = 2; s == 2, t == 1 pt = ps; *pt = 3; t = s; } 20 November 2003 s == 3, t == 1 s == 3, t == 3 CS 201 J Fall 2003 20

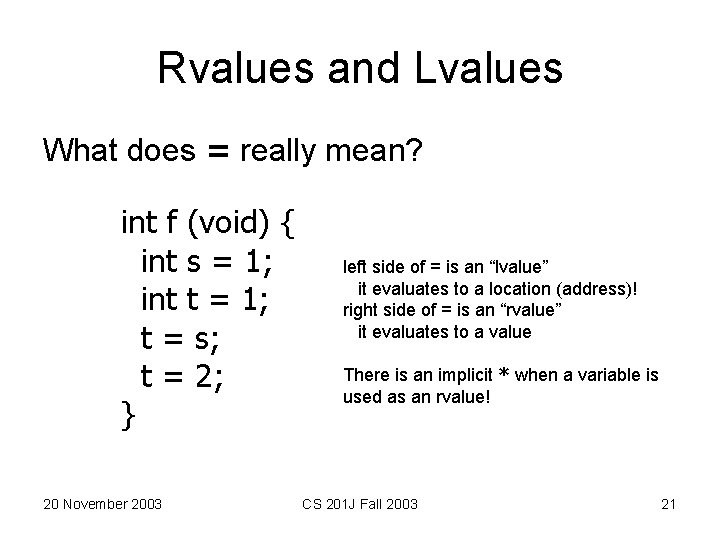

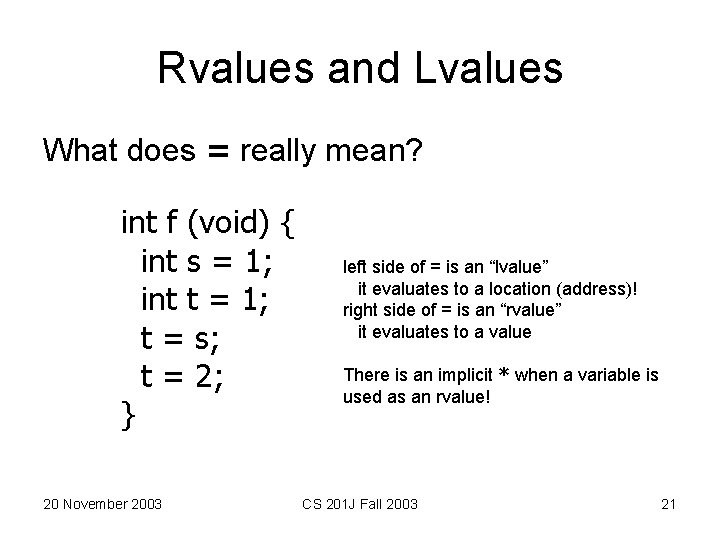

Rvalues and Lvalues What does = really mean? int f (void) { int s = 1; int t = 1; t = s; t = 2; } 20 November 2003 left side of = is an “lvalue” it evaluates to a location (address)! right side of = is an “rvalue” it evaluates to a value There is an implicit * when a variable is used as an rvalue! CS 201 J Fall 2003 21

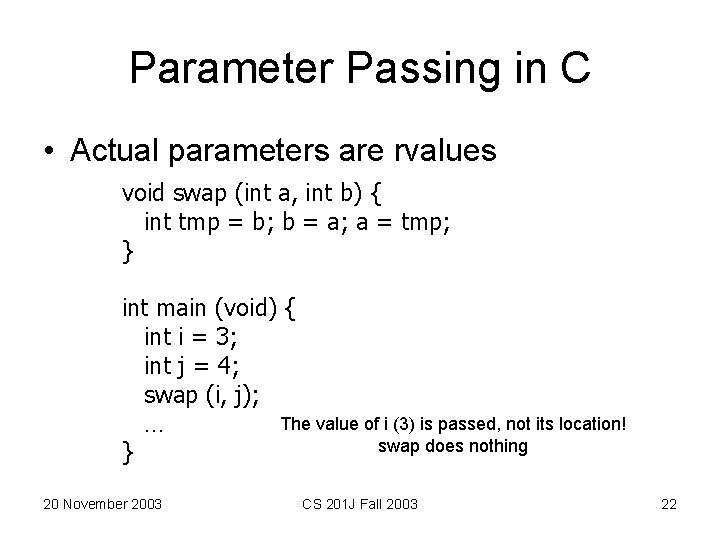

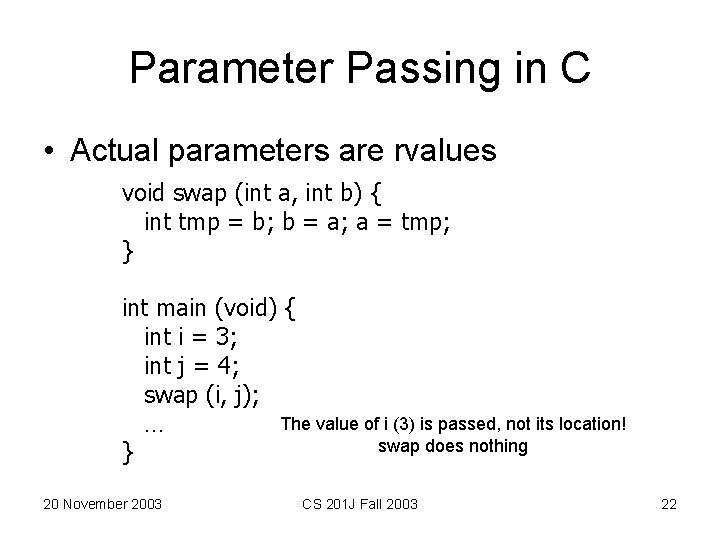

Parameter Passing in C • Actual parameters are rvalues void swap (int a, int b) { int tmp = b; b = a; a = tmp; } int main (void) { int i = 3; int j = 4; swap (i, j); The value of i (3) is passed, not its location! … swap does nothing } 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 22

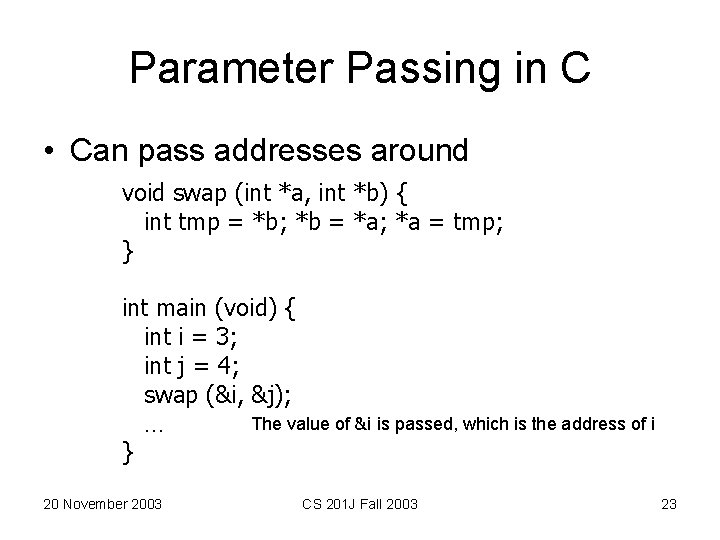

Parameter Passing in C • Can pass addresses around void swap (int *a, int *b) { int tmp = *b; *b = *a; *a = tmp; } int main (void) { int i = 3; int j = 4; swap (&i, &j); The value of &i is passed, which is the address of i … } 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 23

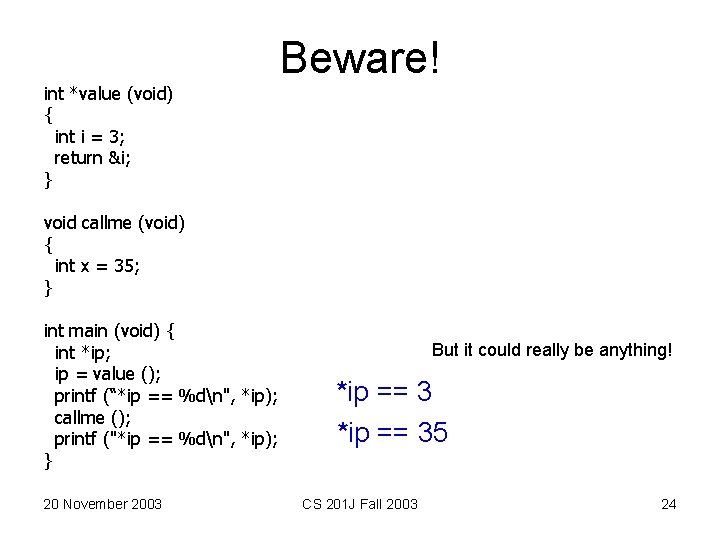

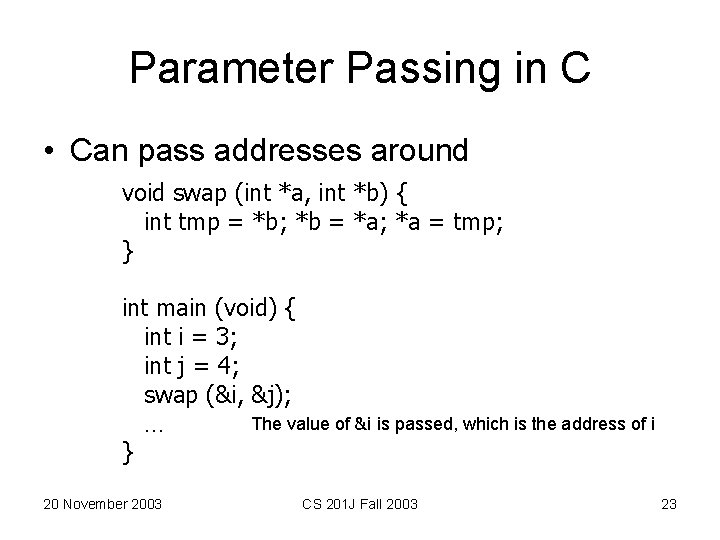

int *value (void) { int i = 3; return &i; } Beware! void callme (void) { int x = 35; } int main (void) { int *ip; ip = value (); printf (“*ip == %dn", *ip); callme (); printf ("*ip == %dn", *ip); } 20 November 2003 But it could really be anything! *ip == 35 CS 201 J Fall 2003 24

![Manipulating Addresses char s6 s0 h expr 1expr 2 in C is just Manipulating Addresses char s[6]; s[0] = ‘h’; expr 1[expr 2] in C is just](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/bf85f32215cf64673ce7455716f67efa/image-25.jpg)

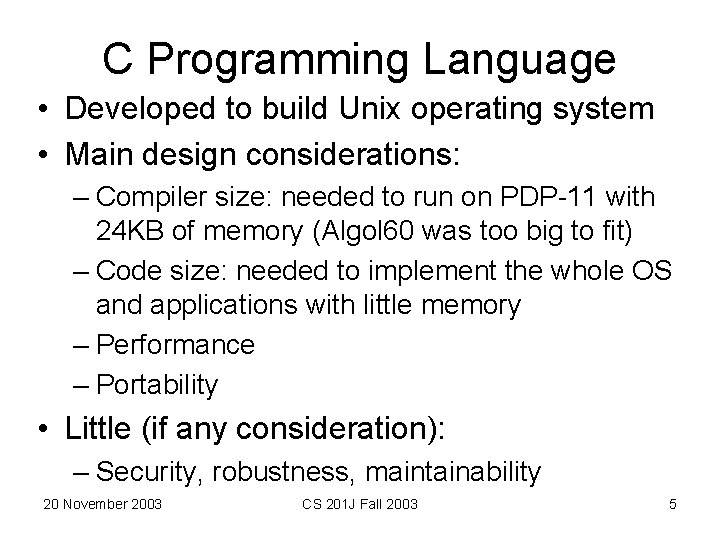

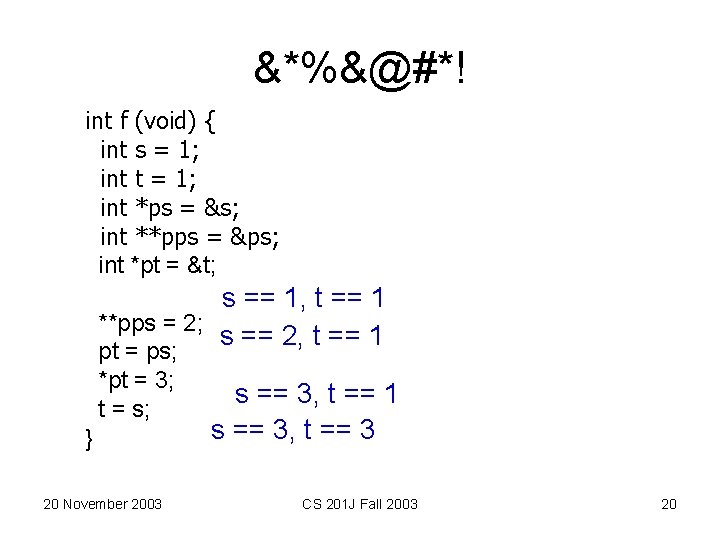

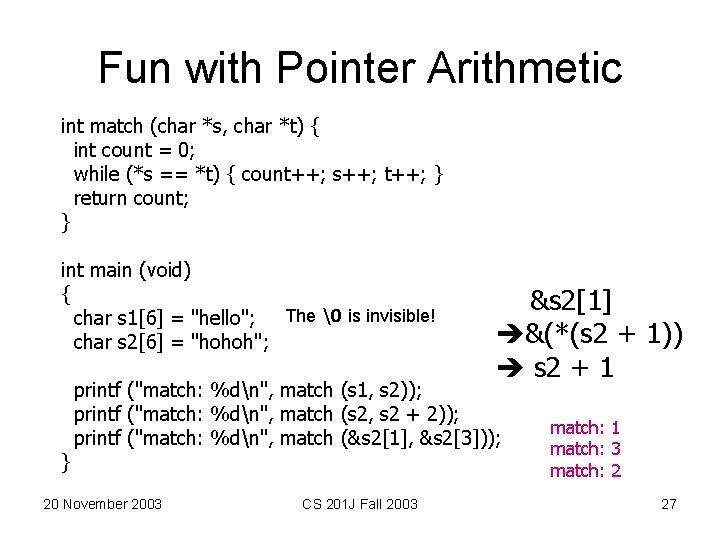

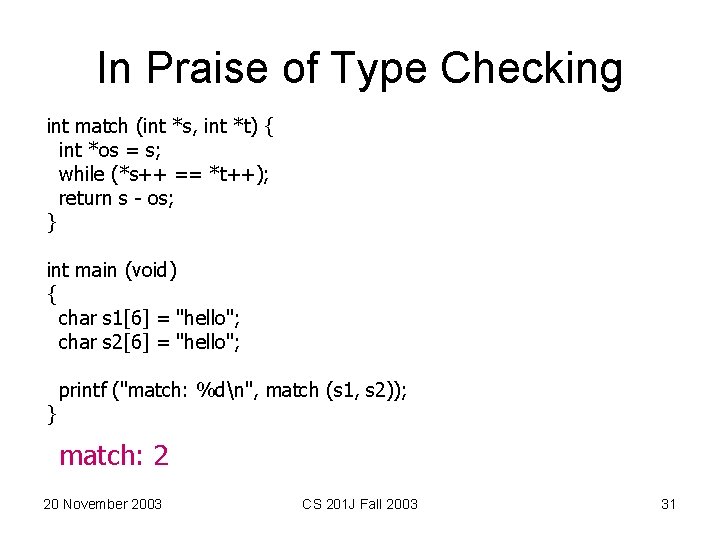

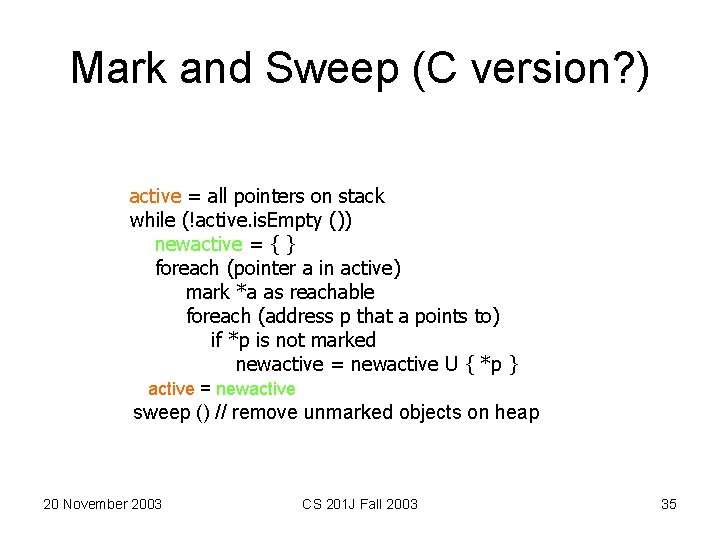

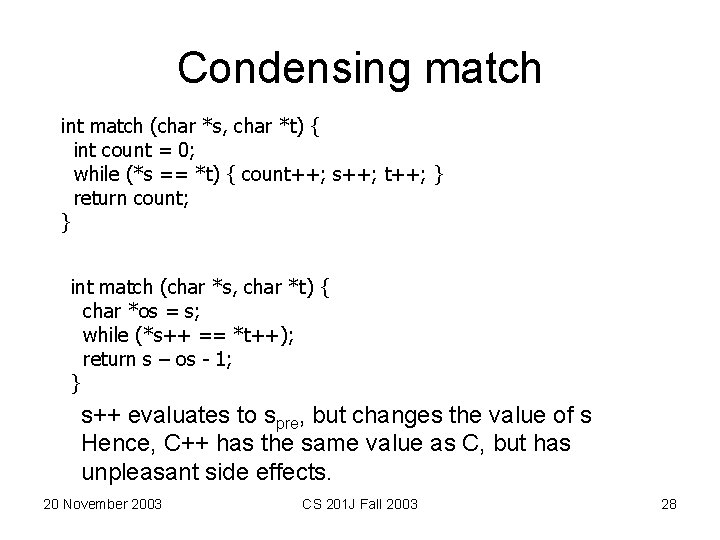

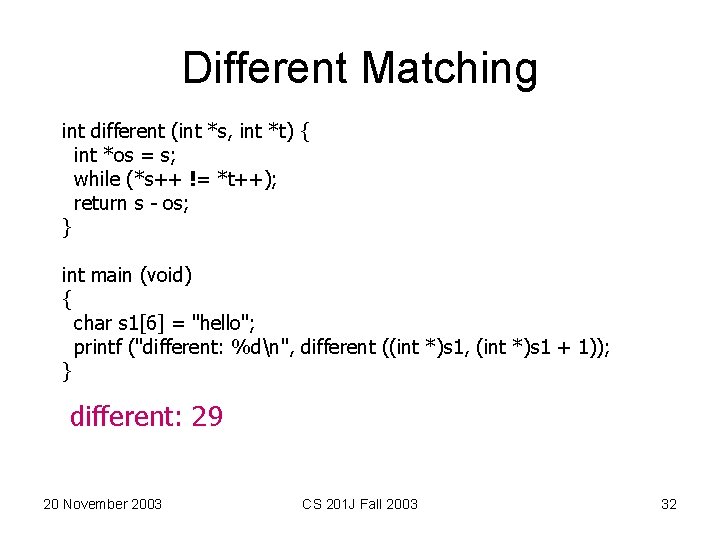

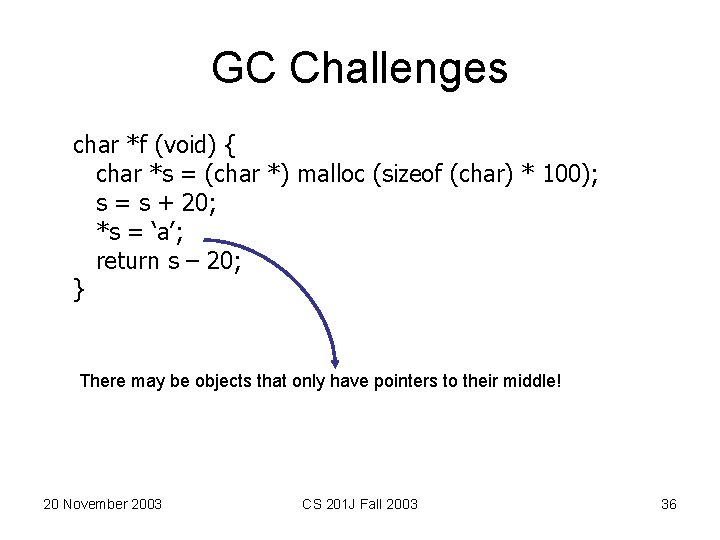

Manipulating Addresses char s[6]; s[0] = ‘h’; expr 1[expr 2] in C is just syntactic sugar for s[1] = ‘e’; *(expr 1 + expr 2) s[2]= ‘l’; s[3] = ‘l’; s[4] = ‘o’; s[5] = ‘�’; printf (“s: %sn”, s); s: hello 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 25

![Obfuscating C char s6 s h s 1 e 2s Obfuscating C char s[6]; *s = ‘h’; *(s + 1) = ‘e’; 2[s] =](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/bf85f32215cf64673ce7455716f67efa/image-26.jpg)

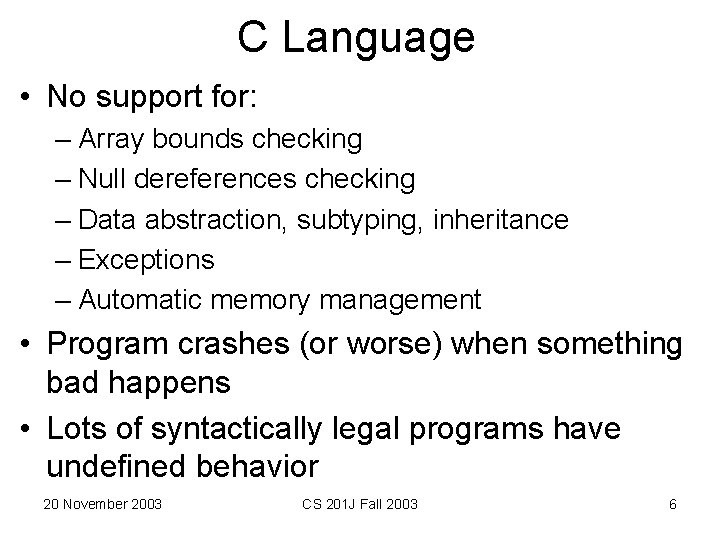

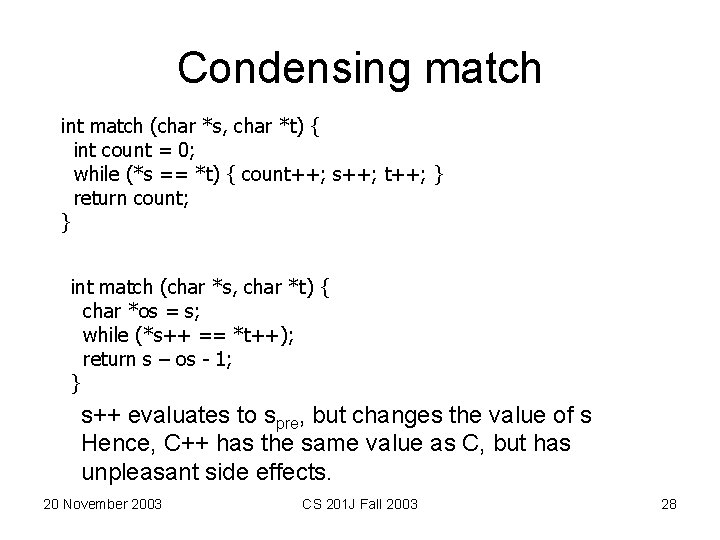

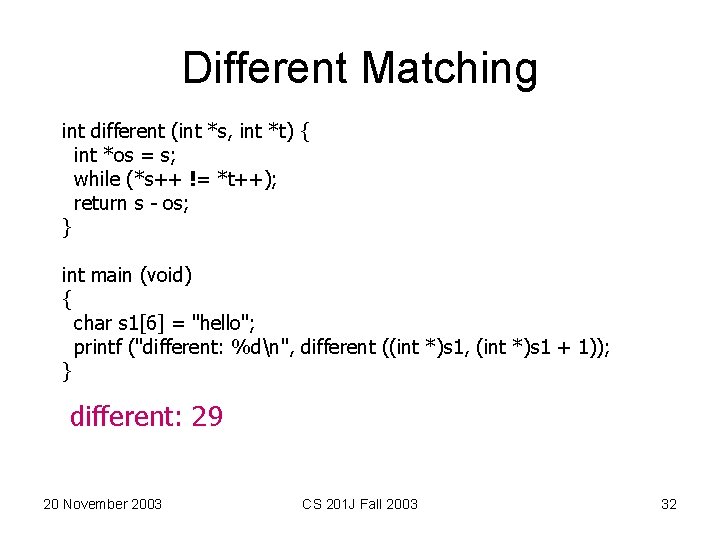

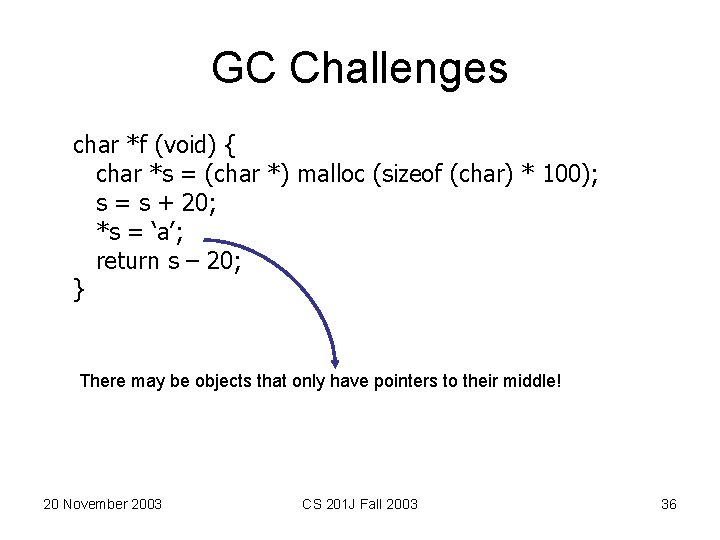

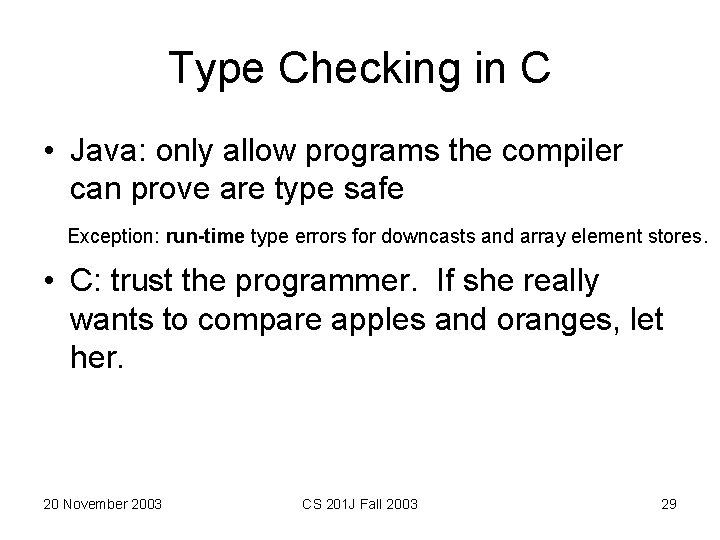

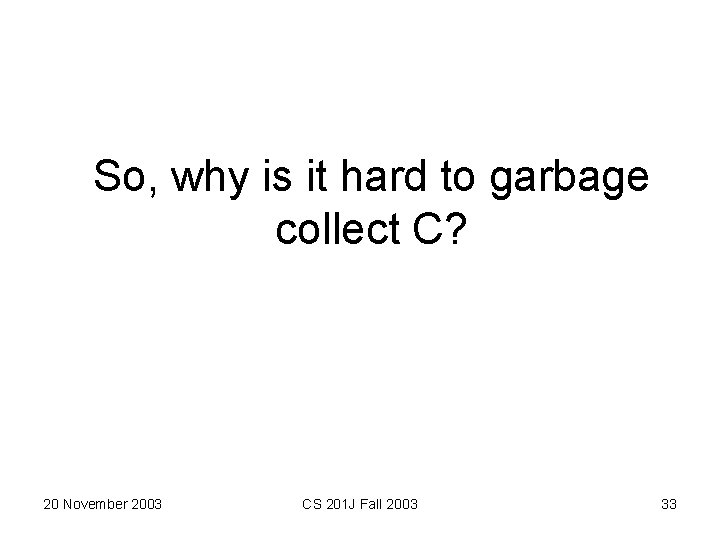

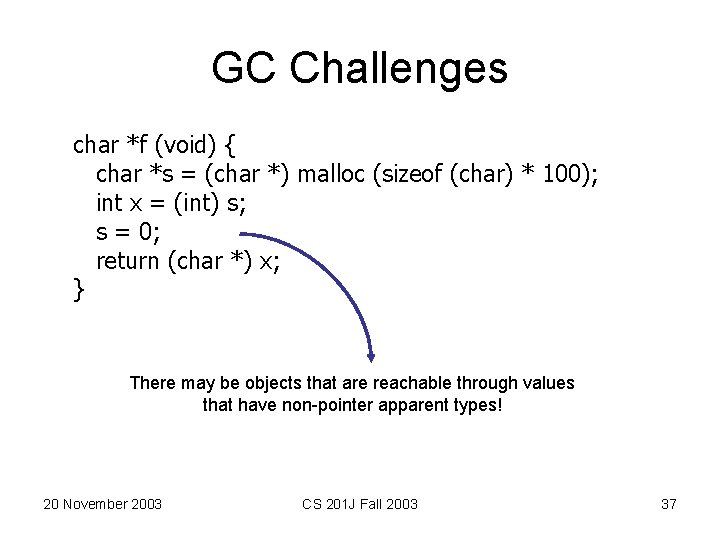

Obfuscating C char s[6]; *s = ‘h’; *(s + 1) = ‘e’; 2[s] = ‘l’; 3[s] = ‘l’; *(s + 4) = ‘o’; 5[s] = ‘�’; printf (“s: %sn”, s); s: hello 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 26

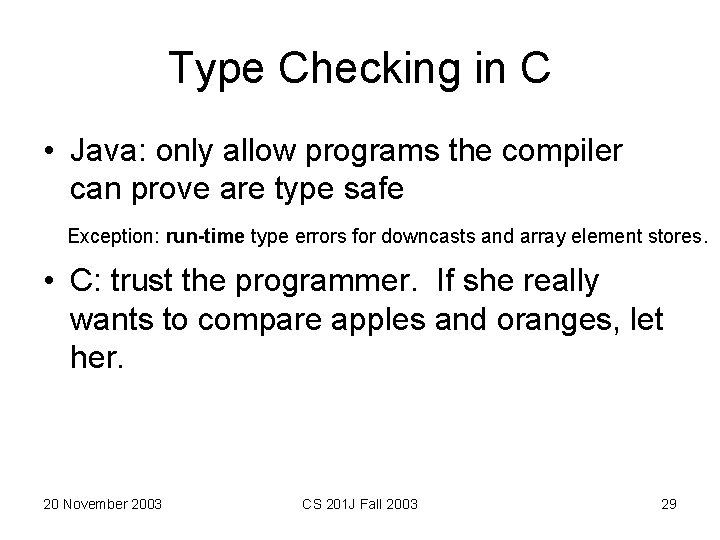

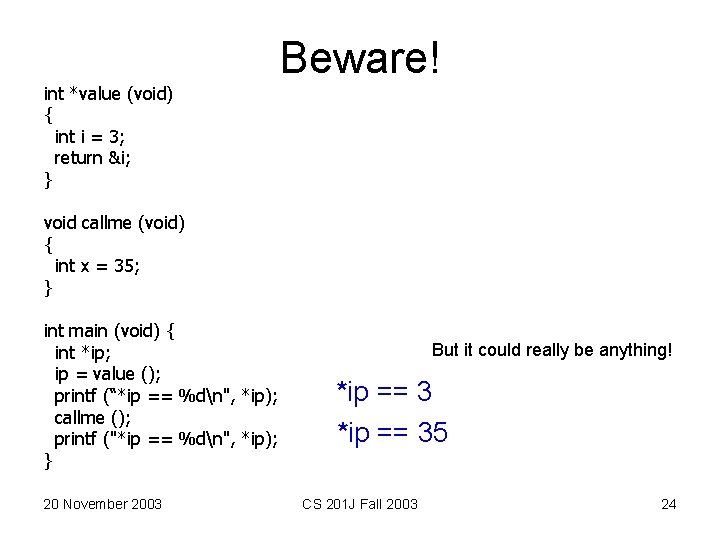

Fun with Pointer Arithmetic int match (char *s, char *t) { int count = 0; while (*s == *t) { count++; s++; t++; } return count; } int main (void) { char s 1[6] = "hello"; The � is invisible! char s 2[6] = "hohoh"; } &s 2[1] &(*(s 2 + 1)) s 2 + 1 printf ("match: %dn", match (s 1, s 2)); printf ("match: %dn", match (s 2, s 2 + 2)); printf ("match: %dn", match (&s 2[1], &s 2[3])); 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 match: 1 match: 3 match: 2 27

Condensing match int match (char *s, char *t) { int count = 0; while (*s == *t) { count++; s++; t++; } return count; } int match (char *s, char *t) { char *os = s; while (*s++ == *t++); return s – os - 1; } s++ evaluates to spre, but changes the value of s Hence, C++ has the same value as C, but has unpleasant side effects. 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 28

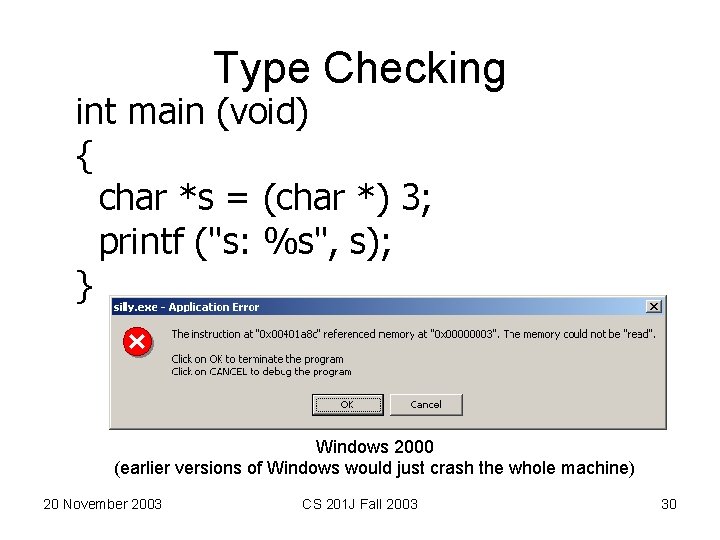

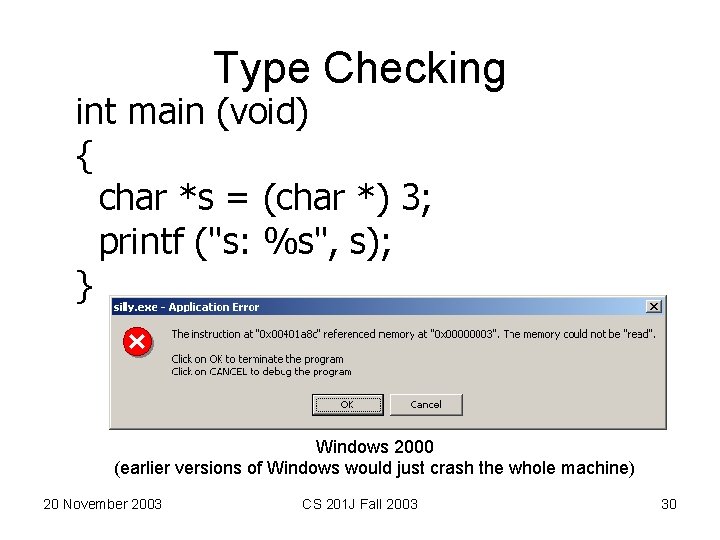

Type Checking in C • Java: only allow programs the compiler can prove are type safe Exception: run-time type errors for downcasts and array element stores. • C: trust the programmer. If she really wants to compare apples and oranges, let her. 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 29

Type Checking int main (void) { char *s = (char *) 3; printf ("s: %s", s); } Windows 2000 (earlier versions of Windows would just crash the whole machine) 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 30

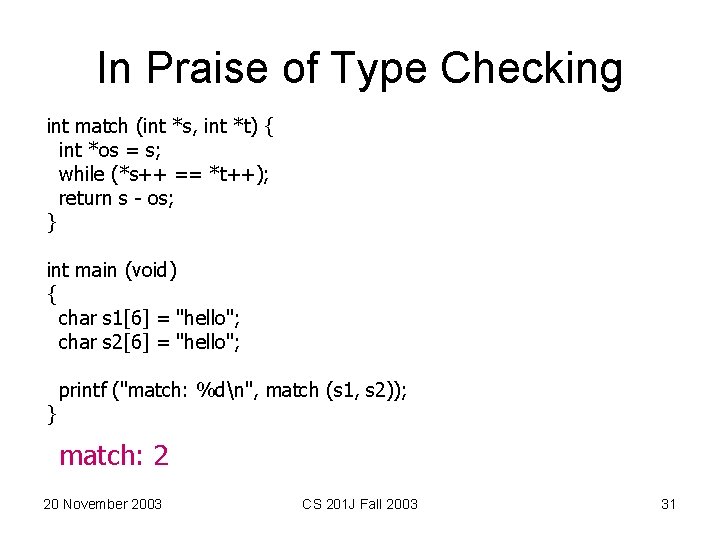

In Praise of Type Checking int match (int *s, int *t) { int *os = s; while (*s++ == *t++); return s - os; } int main (void) { char s 1[6] = "hello"; char s 2[6] = "hello"; } printf ("match: %dn", match (s 1, s 2)); match: 2 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 31

Different Matching int different (int *s, int *t) { int *os = s; while (*s++ != *t++); return s - os; } int main (void) { char s 1[6] = "hello"; printf ("different: %dn", different ((int *)s 1, (int *)s 1 + 1)); } different: 29 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 32

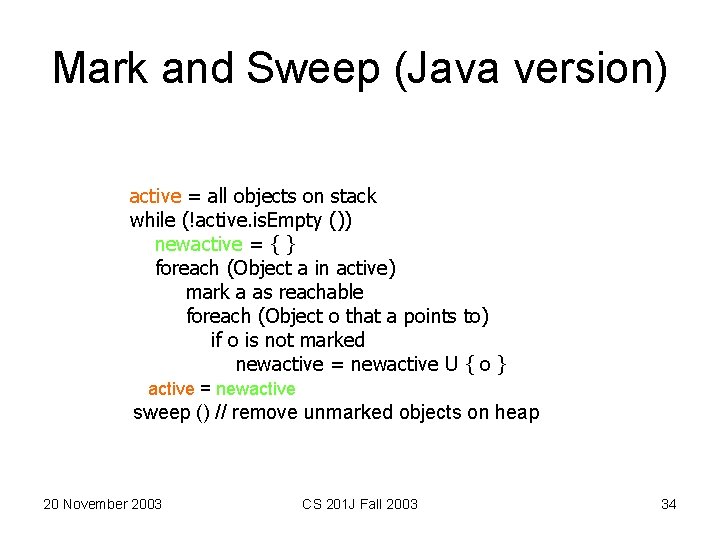

So, why is it hard to garbage collect C? 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 33

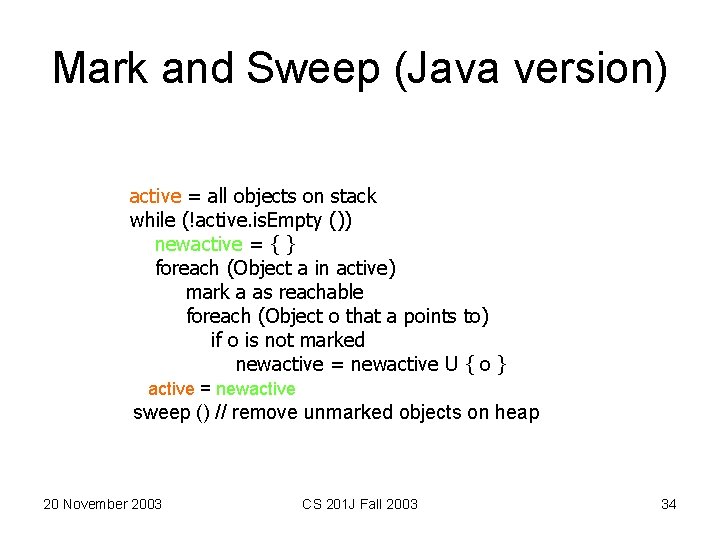

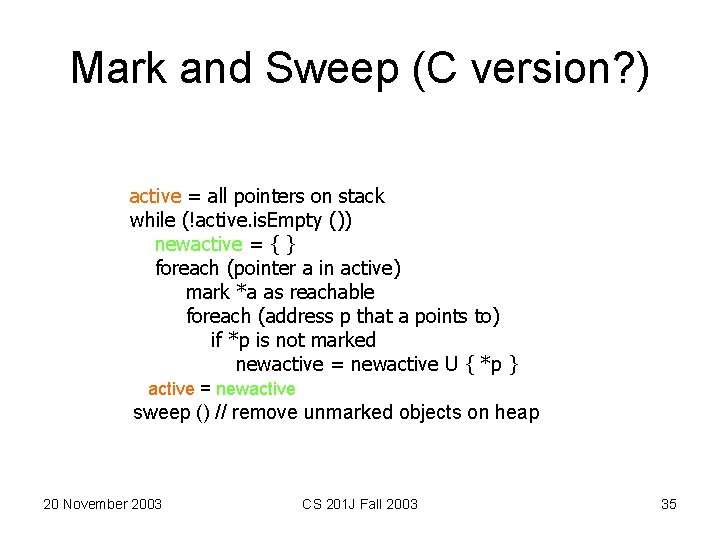

Mark and Sweep (Java version) active = all objects on stack while (!active. is. Empty ()) newactive = { } foreach (Object a in active) mark a as reachable foreach (Object o that a points to) if o is not marked newactive = newactive U { o } active = newactive sweep () // remove unmarked objects on heap 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 34

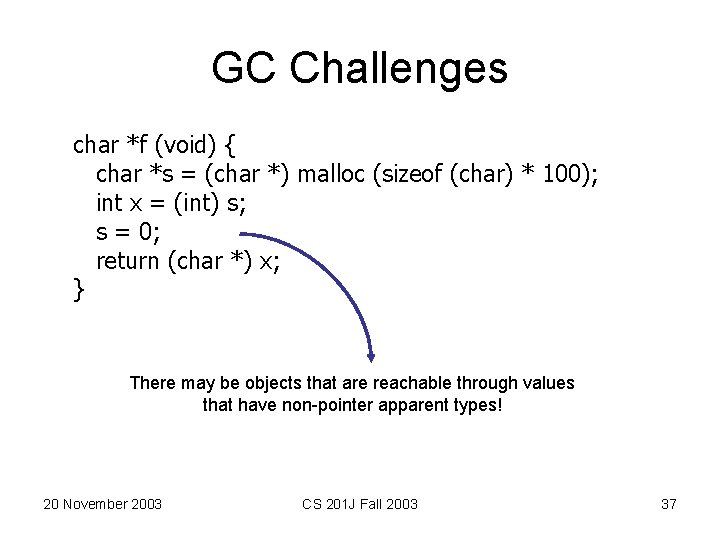

Mark and Sweep (C version? ) active = all pointers on stack while (!active. is. Empty ()) newactive = { } foreach (pointer a in active) mark *a as reachable foreach (address p that a points to) if *p is not marked newactive = newactive U { *p } active = newactive sweep () // remove unmarked objects on heap 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 35

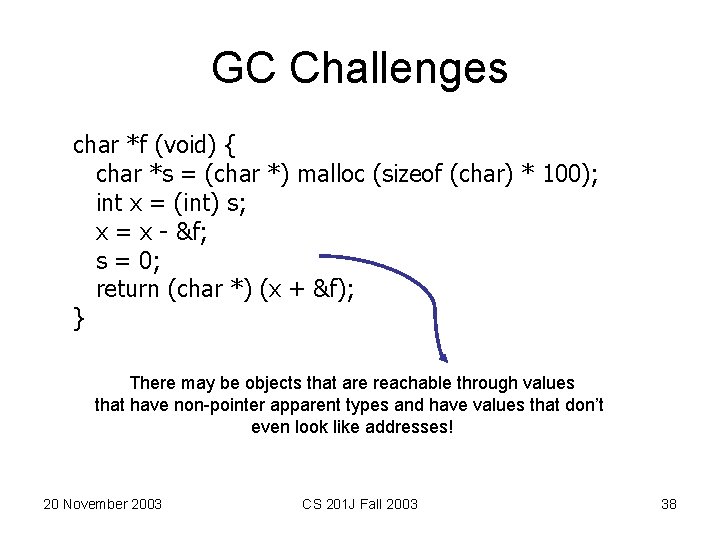

GC Challenges char *f (void) { char *s = (char *) malloc (sizeof (char) * 100); s = s + 20; *s = ‘a’; return s – 20; } There may be objects that only have pointers to their middle! 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 36

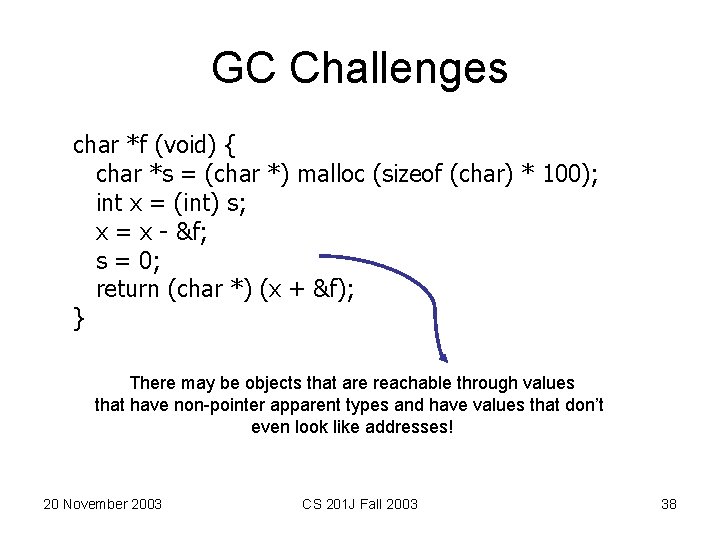

GC Challenges char *f (void) { char *s = (char *) malloc (sizeof (char) * 100); int x = (int) s; s = 0; return (char *) x; } There may be objects that are reachable through values that have non-pointer apparent types! 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 37

GC Challenges char *f (void) { char *s = (char *) malloc (sizeof (char) * 100); int x = (int) s; x = x - &f; s = 0; return (char *) (x + &f); } There may be objects that are reachable through values that have non-pointer apparent types and have values that don’t even look like addresses! 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 38

Why not just do reference counting? Where can you store the references? Remember C programs can access memory directly, better not change how objects are stored! 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 39

Summary • Garbage collection depends on: – Knowing which values are addresses – Knowing that objects without references cannot be reached • Both of these are problems in C • Nevertheless, there are some garbage collectors for C. – Change meaning of some programs – Slow down programs a lot – Are not able to find all garbage 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 40

Charge • Friday’s section: practice problems on subtyping and concurrency • If you send me questions by Monday, Tuesday’s class will be a quiz review • PS 6 due Tuesday – Either staple your assignment before class, or you can use my stapler for $5 per staple 20 November 2003 CS 201 J Fall 2003 41