Lecture 2 Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Lecture

- Slides: 72

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Lecture 2 Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Anthony D. Rosato Granular Science Laboratory ME Department New Jersey Institute of Technology Newark, NJ, USA

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Presentation Outline v Part 1: Background & Motivation v Part 2: Particle Collision Models v Part 3: Wave Propagation Ideas v Part 4: Elastic Impact of Spheres Granular Science Lab - NJIT 2

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Granular Science Lab - NJIT 3

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling is an outgrowth of molecular dynamics simulations used in computational statistical B. J. Alder physics. and T. E. Wainwright, “Statistical mechanical theory of transport properties, ” Proceedings of the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics, Brussels, 1956. W. T. Ashurst and W. G. Hoover, “Argon shear viscosity via a Lennard. Jones potential with equilibrium and nonequilibrium molecular dynamics, ” Phys. Rev. Lett. 31, 206 (1973). However, the discrete element method was independently developed by P. Cundall in the 1970’s. P. A. Cundall, Symposium of the International Society of Rock Mechanics, ” Nancy, France (1971). P. A. Cundall, “Computer model for rock-mass behavior using interactive graphics for input and output of geometrical data, ” U. S. Army Corps. Of Engineers, Technical Report No. MRD, 1974, p. 2074. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 4

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Basic Idea of DEM Modeling Approximate the collisional interactions between particles using idealized force models that dissipate energy. Integrate system equations of motion Determine individual particle positions and velocities. Compute relevant transport quantities, bulk properties and analyze evolving microstructure. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 5

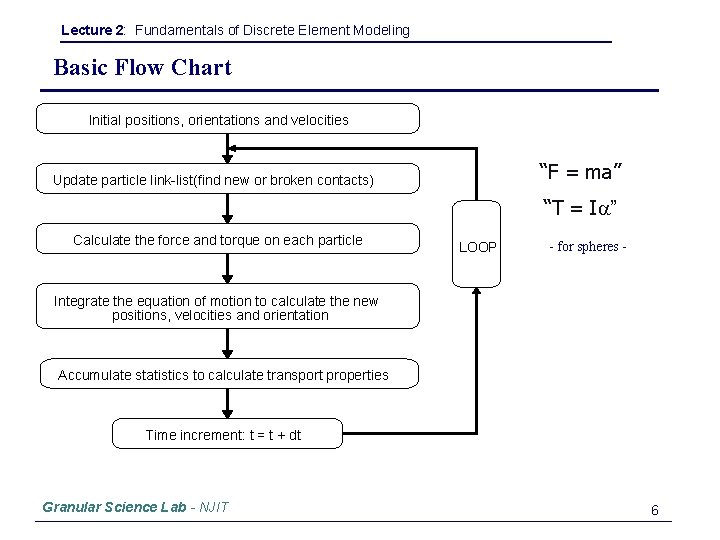

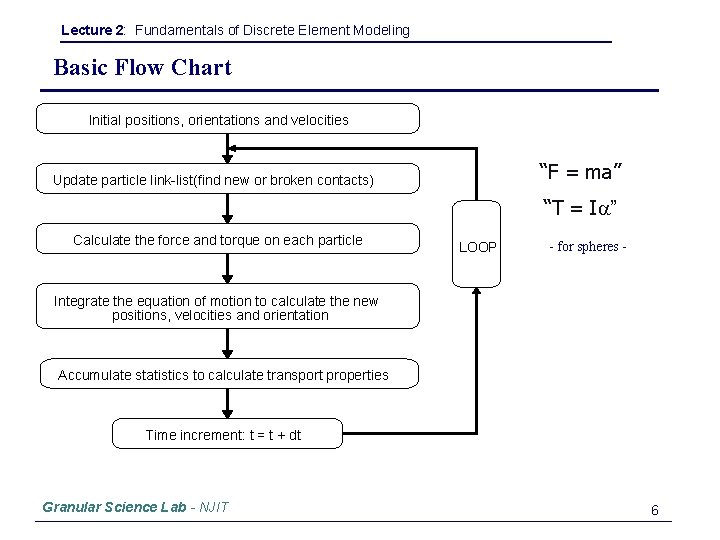

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Basic Flow Chart Initial positions, orientations and velocities “F = ma” Update particle link-list(find new or broken contacts) “T = Ia” Calculate the force and torque on each particle LOOP - for spheres - Integrate the equation of motion to calculate the new positions, velocities and orientation Accumulate statistics to calculate transport properties Time increment: t = t + dt Granular Science Lab - NJIT 6

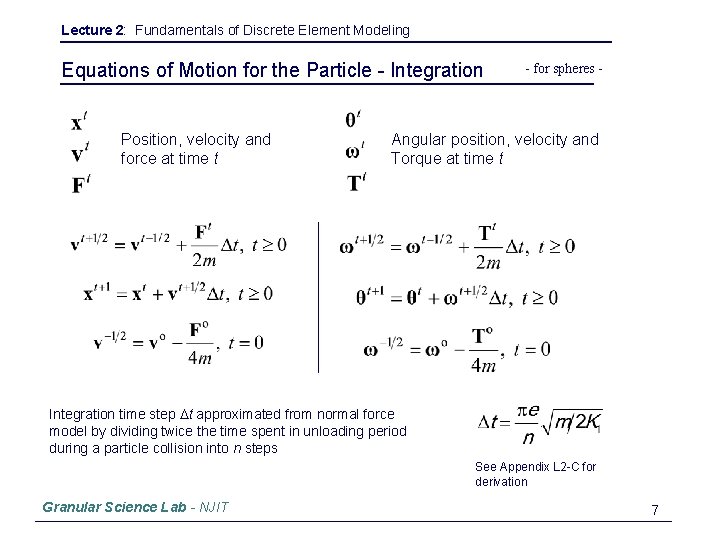

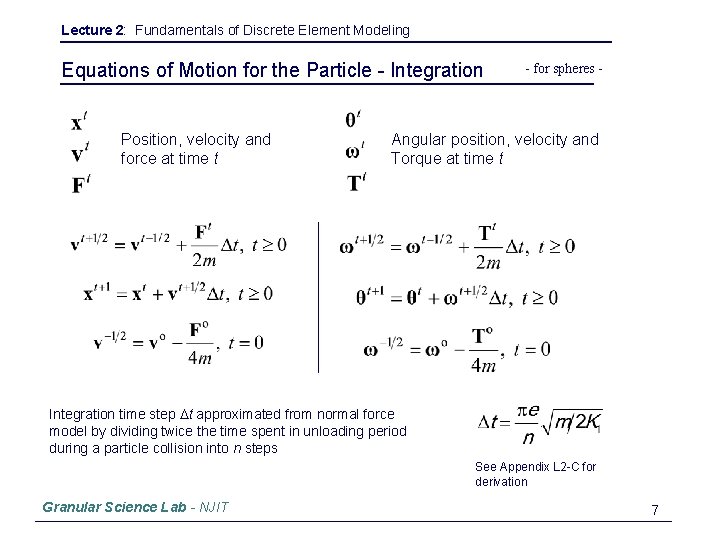

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Equations of Motion for the Particle - Integration Position, velocity and force at time t - for spheres - Angular position, velocity and Torque at time t Integration time step t approximated from normal force model by dividing twice the time spent in unloading period during a particle collision into n steps See Appendix L 2 -C for derivation Granular Science Lab - NJIT 7

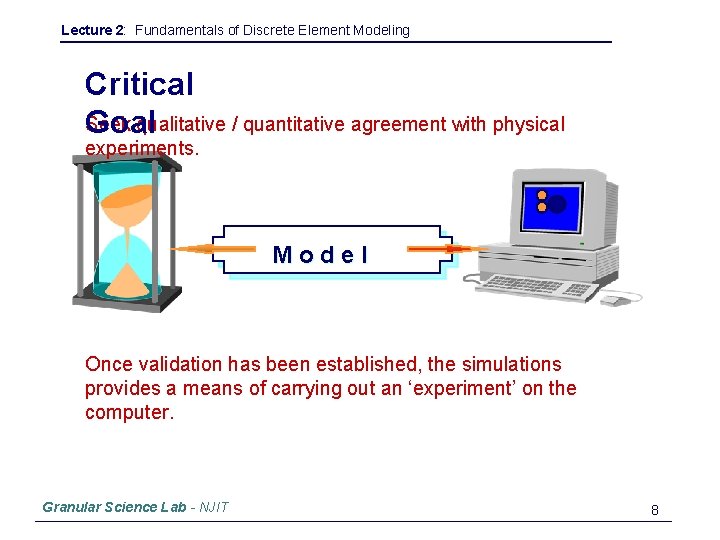

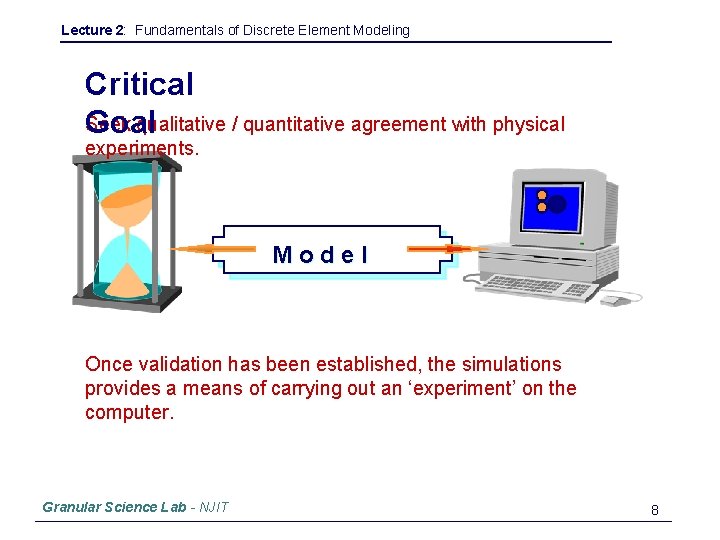

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Critical Seek qualitative / quantitative agreement with physical Goal experiments. Model Once validation has been established, the simulations provides a means of carrying out an ‘experiment’ on the computer. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 8

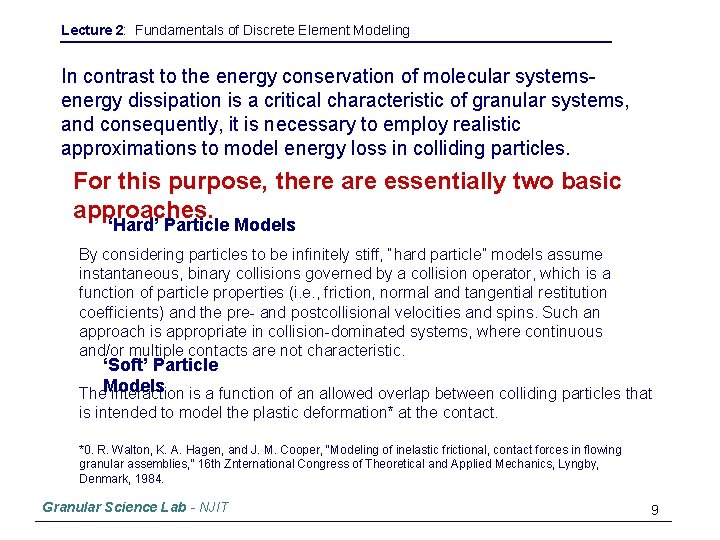

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling In contrast to the energy conservation of molecular systemsenergy dissipation is a critical characteristic of granular systems, and consequently, it is necessary to employ realistic approximations to model energy loss in colliding particles. For this purpose, there are essentially two basic approaches. ‘Hard’ Particle Models By considering particles to be infinitely stiff, “hard particle” models assume instantaneous, binary collisions governed by a collision operator, which is a function of particle properties (i. e. , friction, normal and tangential restitution coefficients) and the pre- and postcollisional velocities and spins. Such an approach is appropriate in collision-dominated systems, where continuous and/or multiple contacts are not characteristic. ‘Soft’ Particle The. Models interaction is a function of an allowed overlap between colliding particles that is intended to model the plastic deformation* at the contact. *0. R. Walton, K. A. Hagen, and J. M. Cooper, “Modeling of inelastic frictional, contact forces in flowing granu. Iar assemblies, ” 16 th Znternational Congress of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Lyngby, Denmark, 1984. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 9

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Granular Science Lab - NJIT 10

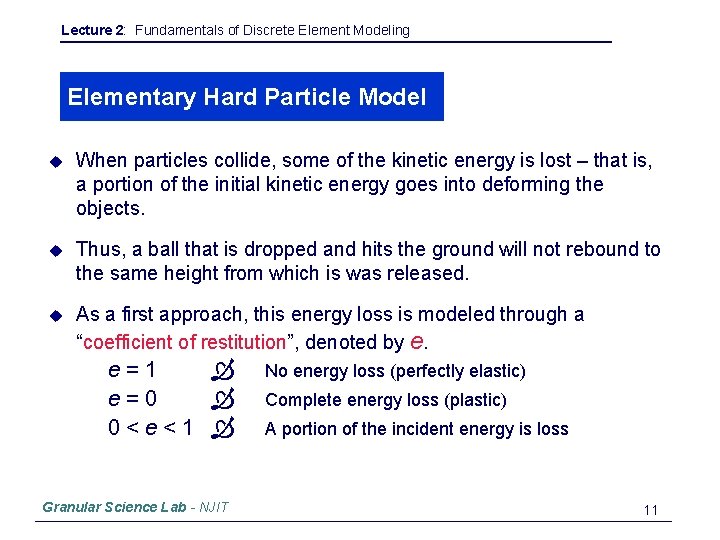

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Elementary Hard Particle Model u When particles collide, some of the kinetic energy is lost – that is, a portion of the initial kinetic energy goes into deforming the objects. u Thus, a ball that is dropped and hits the ground will not rebound to the same height from which is was released. u As a first approach, this energy loss is modeled through a “coefficient of restitution”, denoted by e. e=1 e=0 0<e<1 Granular Science Lab - NJIT No energy loss (perfectly elastic) Complete energy loss (plastic) A portion of the incident energy is loss 11

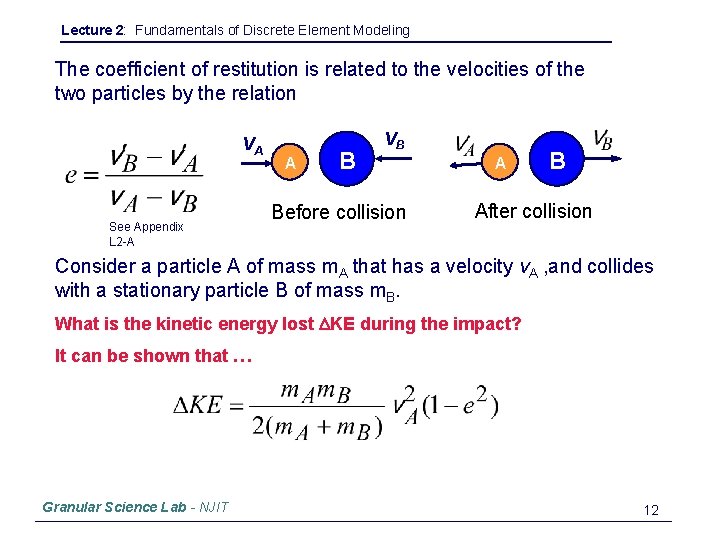

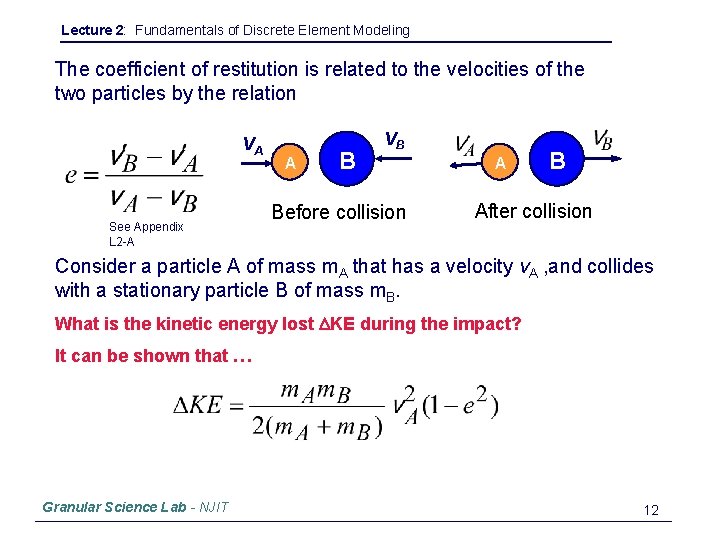

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling The coefficient of restitution is related to the velocities of the two particles by the relation VA See Appendix L 2 -A A B VB Before collision A B After collision Consider a particle A of mass m. A that has a velocity v. A , and collides with a stationary particle B of mass m. B. What is the kinetic energy lost DKE during the impact? It can be shown that … Granular Science Lab - NJIT 12

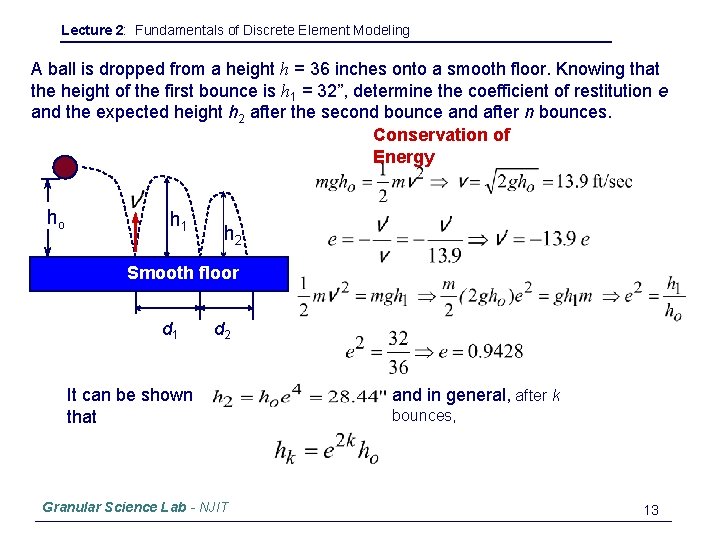

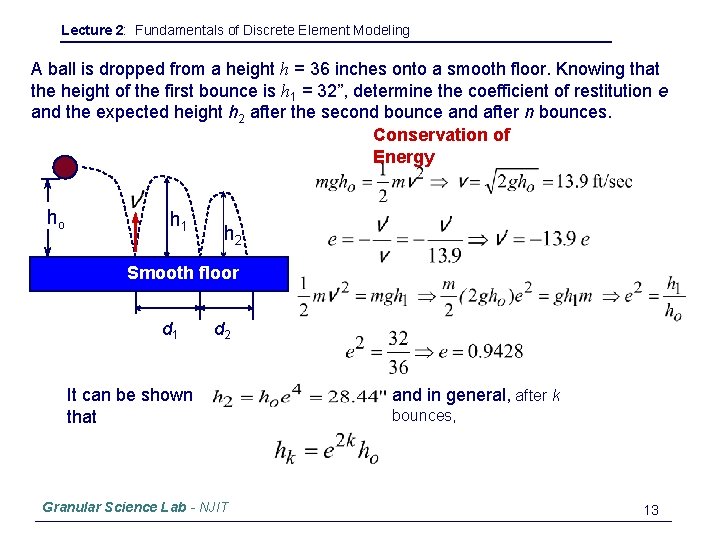

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling A ball is dropped from a height h = 36 inches onto a smooth floor. Knowing that the height of the first bounce is h 1 = 32”, determine the coefficient of restitution e and the expected height h 2 after the second bounce and after n bounces. Conservation of Energy ho h 1 h 2 Smooth floor d 1 d 2 It can be shown that Granular Science Lab - NJIT and in general, after k bounces, 13

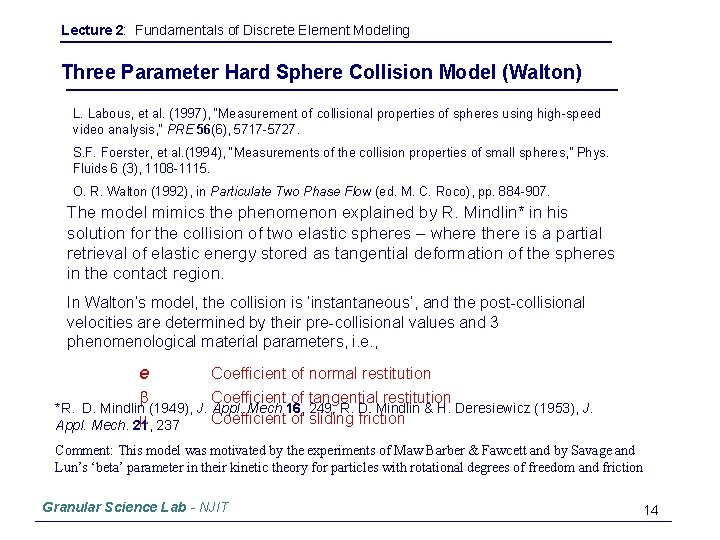

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Three Parameter Hard Sphere Collision Model (Walton) L. Labous, et al. (1997), “Measurement of collisional properties of spheres using high-speed video analysis, ” PRE 56(6), 5717 -5727. S. F. Foerster, et al. (1994), “Measurements of the collision properties of small spheres, ” Phys. Fluids 6 (3), 1108 -1115. O. R. Walton (1992), in Particulate Two Phase Flow (ed. M. C. Roco), pp. 884 -907. The model mimics the phenomenon explained by R. Mindlin* in his solution for the collision of two elastic spheres – where there is a partial retrieval of elastic energy stored as tangential deformation of the spheres in the contact region. In Walton’s model, the collision is ‘instantaneous’, and the post-collisional velocities are determined by their pre-collisional values and 3 phenomenological material parameters, i. e. , e b Coefficient of normal restitution Coefficient of tangential restitution *R. D. Mindlin (1949), J. Appl. Mech 16, 249; R. D. Mindlin & H. Deresiewicz (1953), J. m 237 Coefficient of sliding friction Appl. Mech. 21, Comment: This model was motivated by the experiments of Maw Barber & Fawcett and by Savage and Lun’s ‘beta’ parameter in their kinetic theory for particles with rotational degrees of freedom and friction Granular Science Lab - NJIT 14

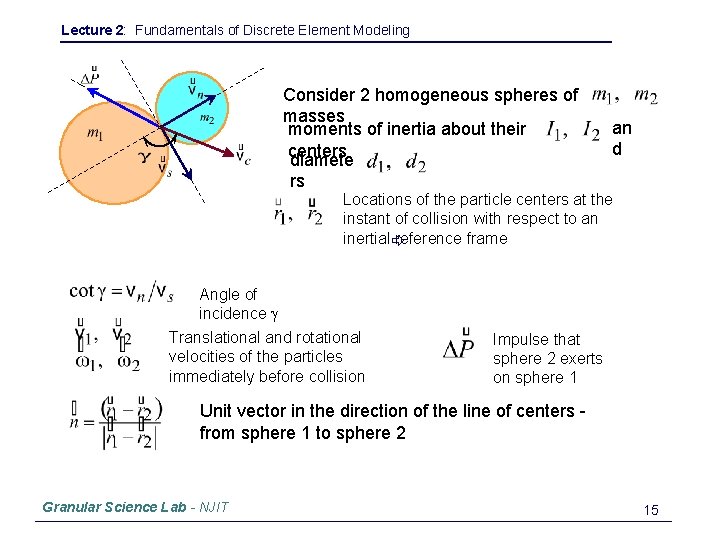

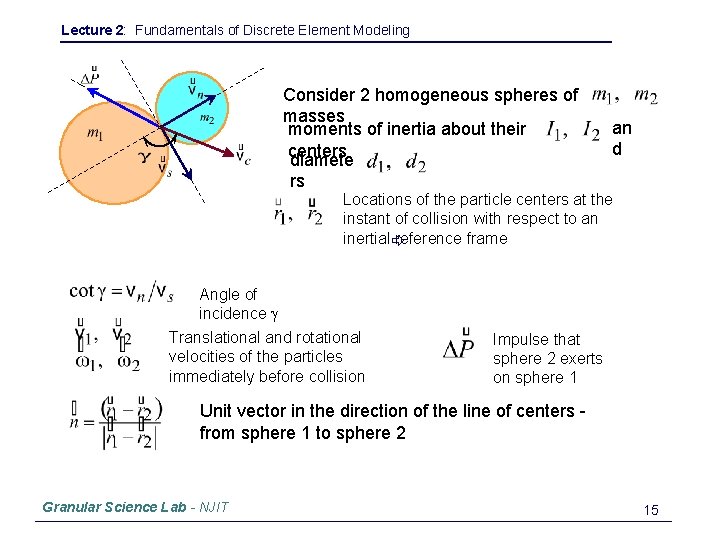

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Consider 2 homogeneous spheres of masses moments of inertia about their centers diamete rs an d Locations of the particle centers at the instant of collision with respect to an inertial reference frame Angle of incidence g Translational and rotational velocities of the particles immediately before collision Impulse that sphere 2 exerts on sphere 1 Unit vector in the direction of the line of centers from sphere 1 to sphere 2 Granular Science Lab - NJIT 15

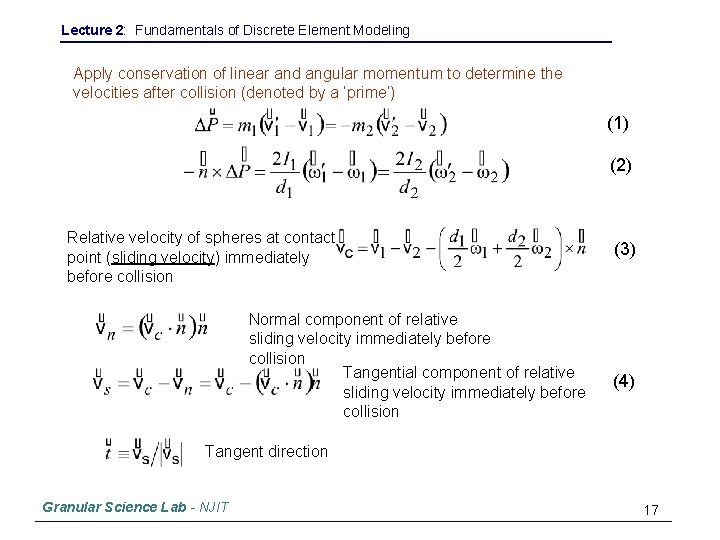

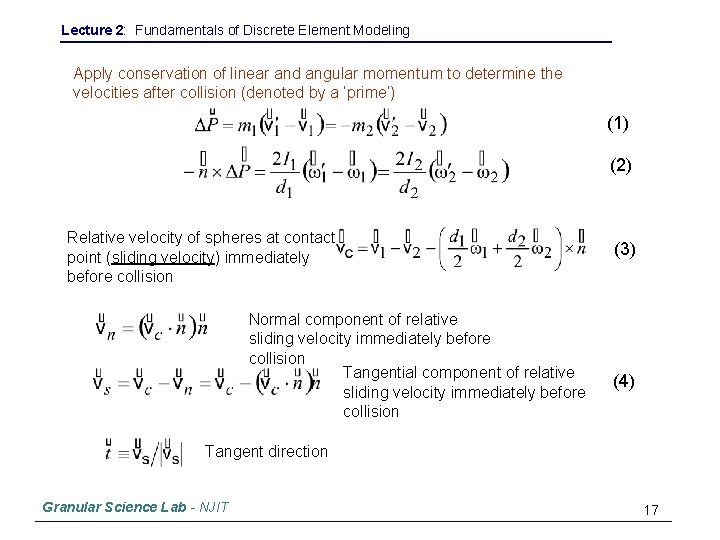

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Apply conservation of linear and angular momentum to determine the velocities after collision (denoted by a ‘prime’) (1) (2) Relative velocity of spheres at contact point (sliding velocity) immediately before collision Normal component of relative sliding velocity immediately before collision Tangential component of relative sliding velocity immediately before collision (3) (4) Tangent direction Granular Science Lab - NJIT 17

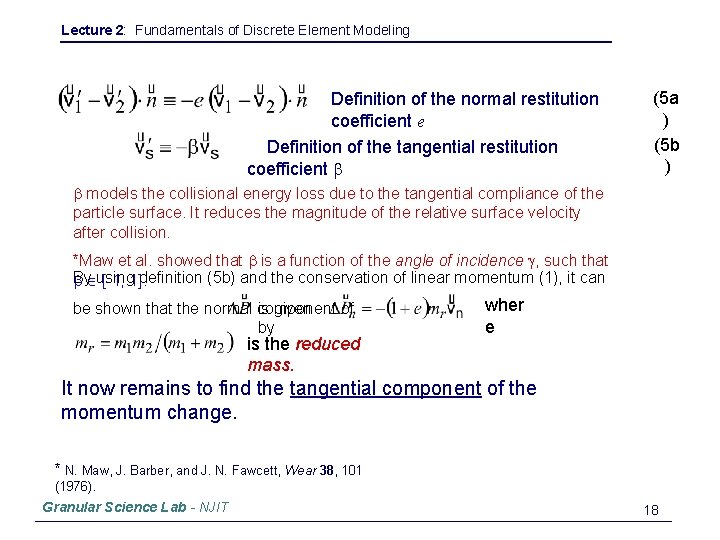

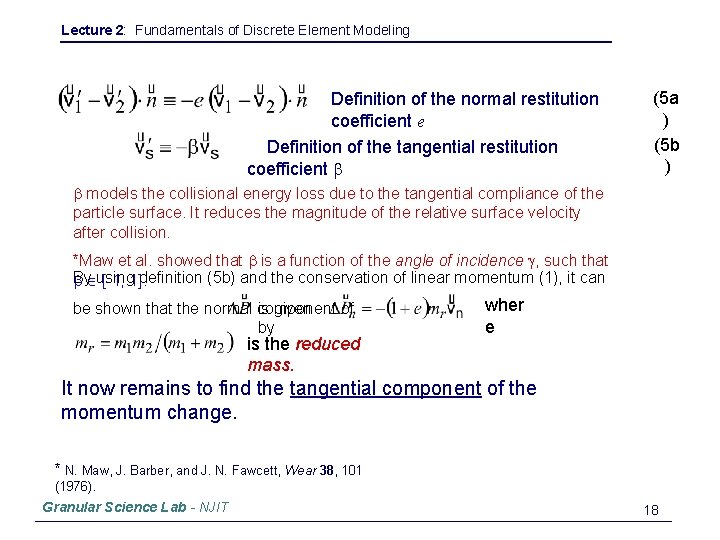

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Definition of the normal restitution coefficient e Definition of the tangential restitution coefficient b (5 a ) (5 b ) b models the collisional energy loss due to the tangential compliance of the particle surface. It reduces the magnitude of the relative surface velocity after collision. *Maw et al. showed that b is a function of the angle of incidence g, such that By definition (5 b) and the conservation of linear momentum (1), it can b using [-1, 1]. is given be shown that the normal component of by is the reduced mass. wher e It now remains to find the tangential component of the momentum change. * N. Maw, J. Barber, and J. N. Fawcett, Wear 38, 101 (1976). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 18

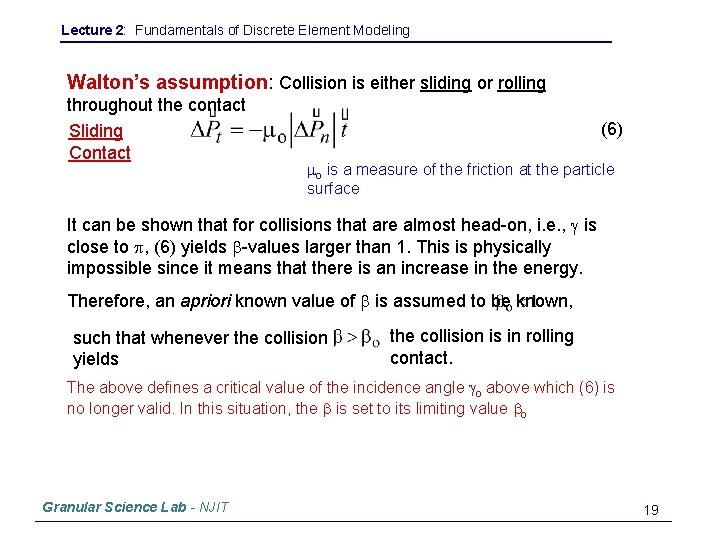

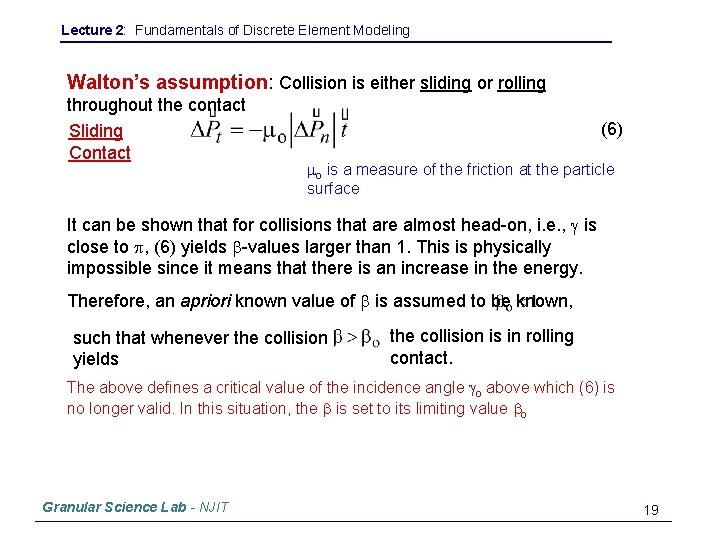

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Walton’s assumption: Collision is either sliding or rolling throughout the contact Sliding Contact (6) mo is a measure of the friction at the particle surface It can be shown that for collisions that are almost head-on, i. e. , g is close to p, (6) yields b-values larger than 1. This is physically impossible since it means that there is an increase in the energy. Therefore, an apriori known value of b is assumed to be known, such that whenever the collision yields the collision is in rolling contact. The above defines a critical value of the incidence angle go above which (6) is no longer valid. In this situation, the b is set to its limiting value bo Granular Science Lab - NJIT 19

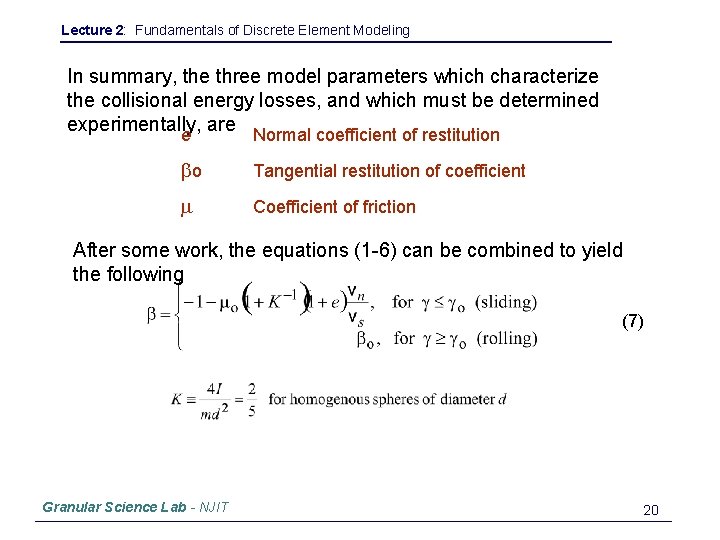

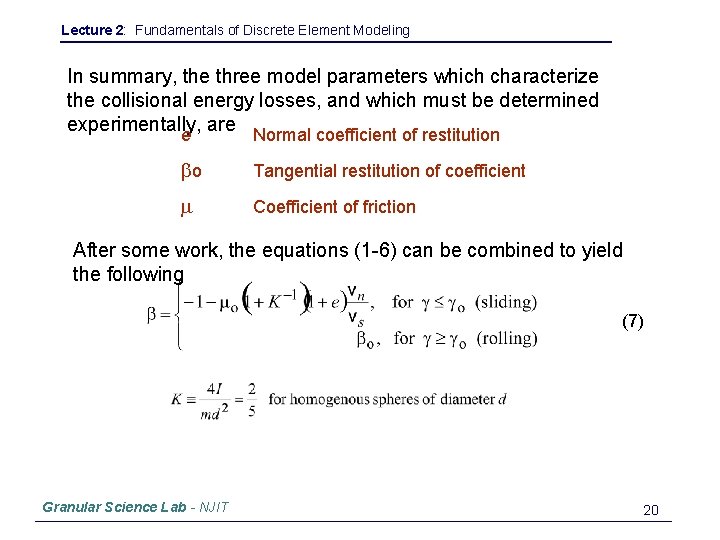

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling In summary, the three model parameters which characterize the collisional energy losses, and which must be determined experimentally, are e Normal coefficient of restitution bo Tangential restitution of coefficient m Coefficient of friction After some work, the equations (1 -6) can be combined to yield the following (7) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 20

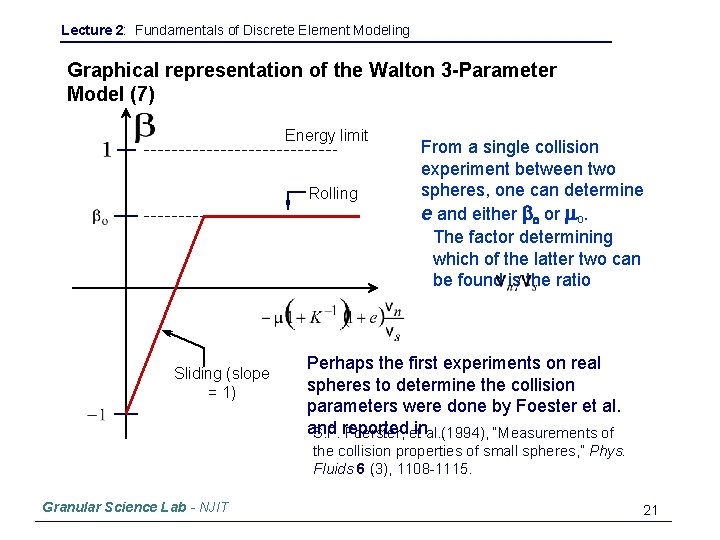

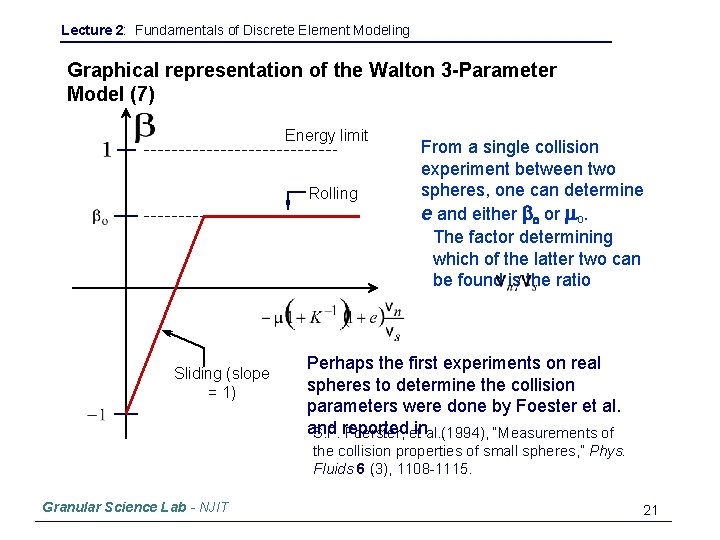

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Graphical representation of the Walton 3 -Parameter Model (7) Energy limit Rolling Sliding (slope = 1) From a single collision experiment between two spheres, one can determine e and either bo or mo. The factor determining which of the latter two can be found is the ratio Perhaps the first experiments on real spheres to determine the collision parameters were done by Foester et al. and S. F. reported Foerster, etinal. (1994), “Measurements of the collision properties of small spheres, ” Phys. Fluids 6 (3), 1108 -1115. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 21

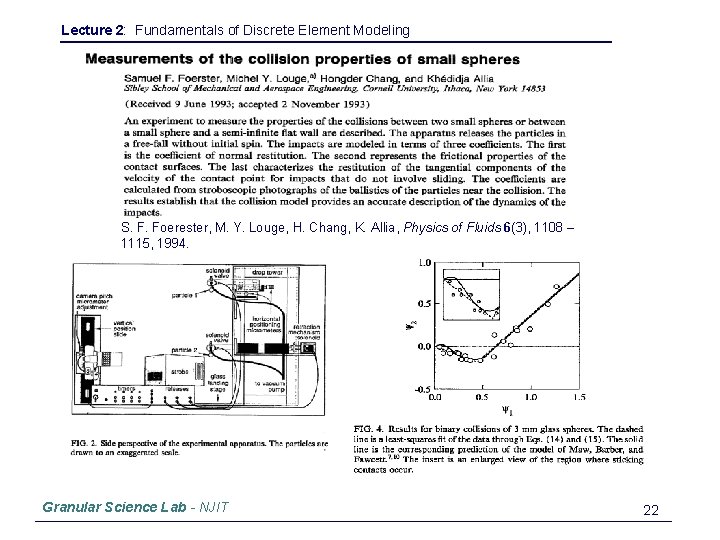

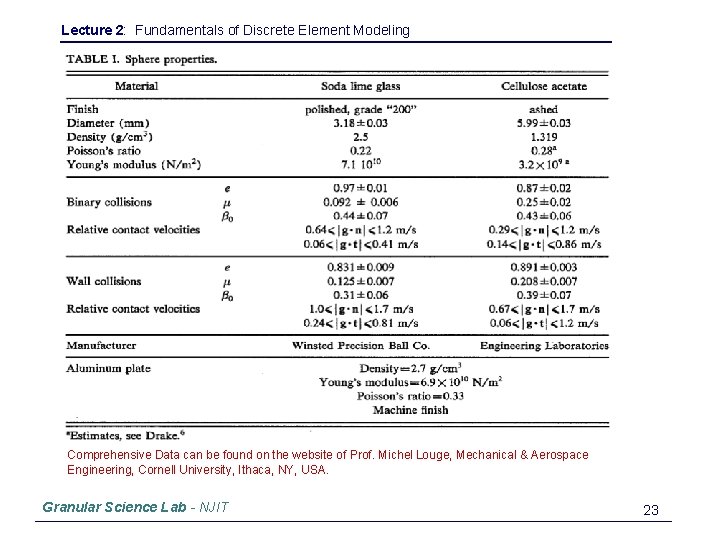

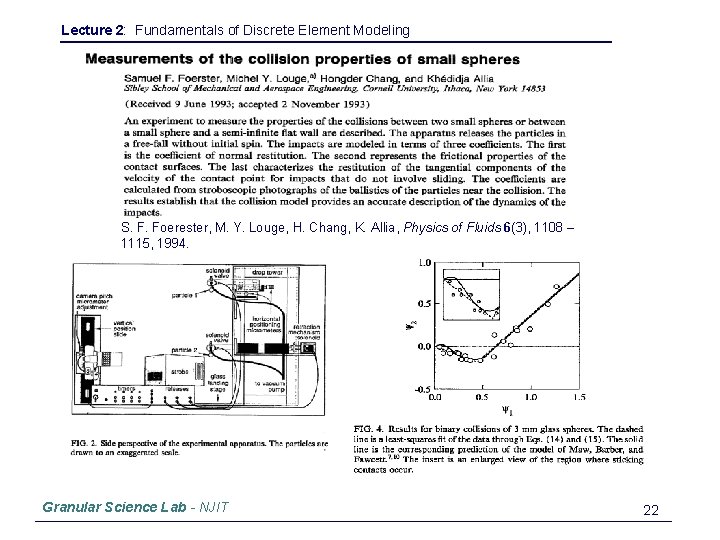

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling S. F. Foerester, M. Y. Louge, H. Chang, K. Allia, Physics of Fluids 6(3), 1108 – 1115, 1994. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 22

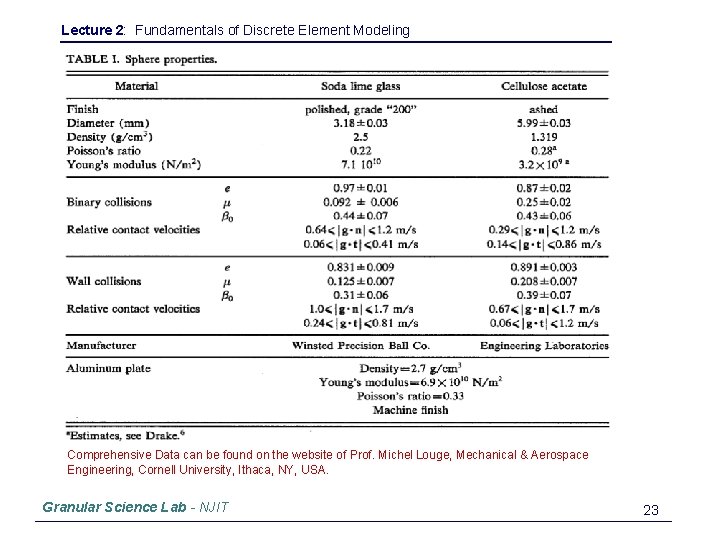

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Comprehensive Data can be found on the website of Prof. Michel Louge, Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 23

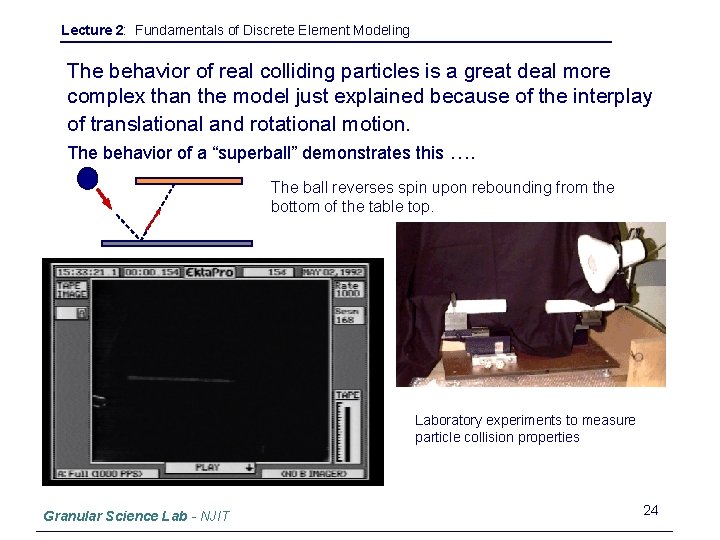

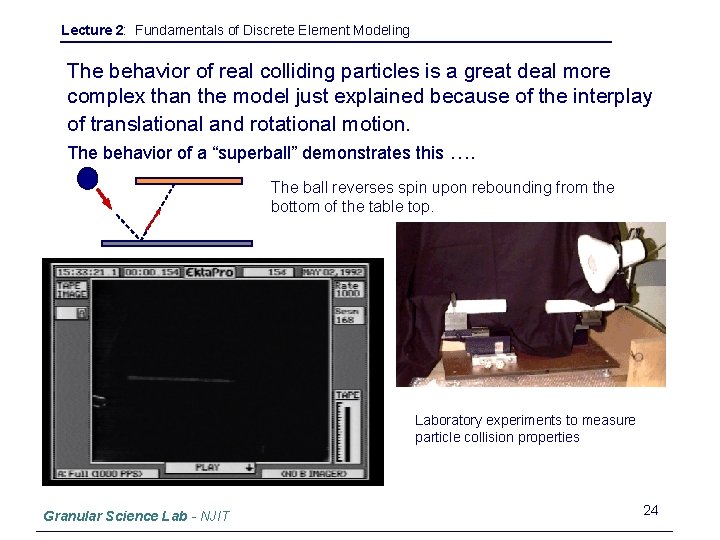

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling The behavior of real colliding particles is a great deal more complex than the model just explained because of the interplay of translational and rotational motion. The behavior of a “superball” demonstrates this …. The ball reverses spin upon rebounding from the bottom of the table top. Laboratory experiments to measure particle collision properties Granular Science Lab - NJIT 24

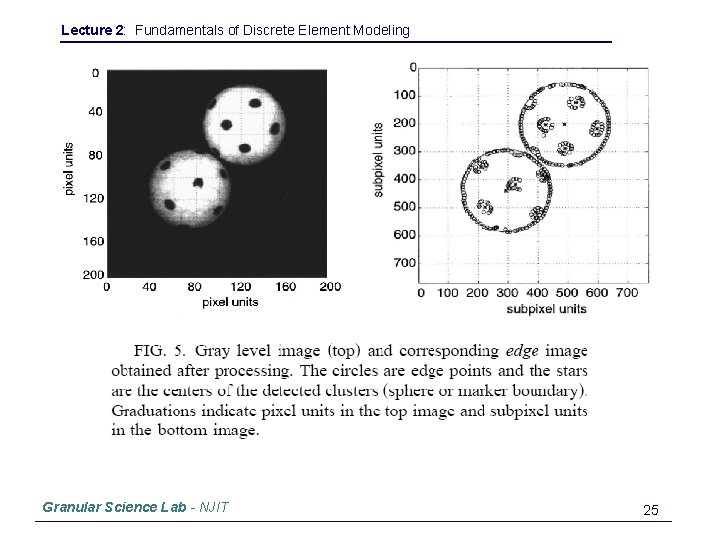

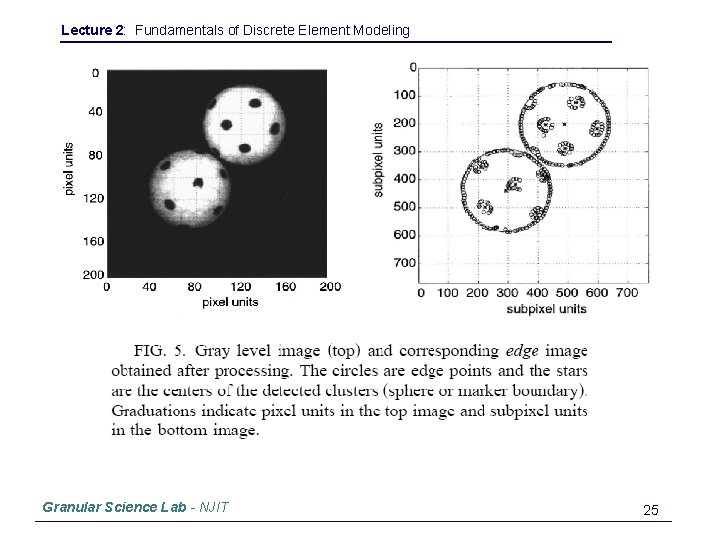

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Granular Science Lab - NJIT 25

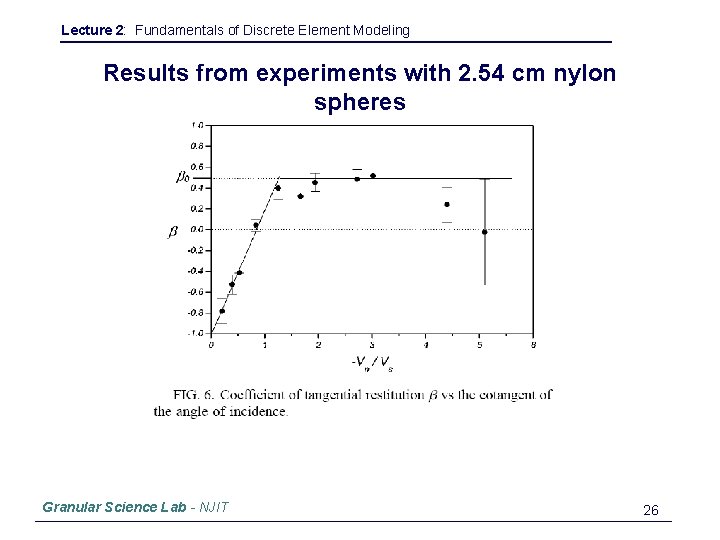

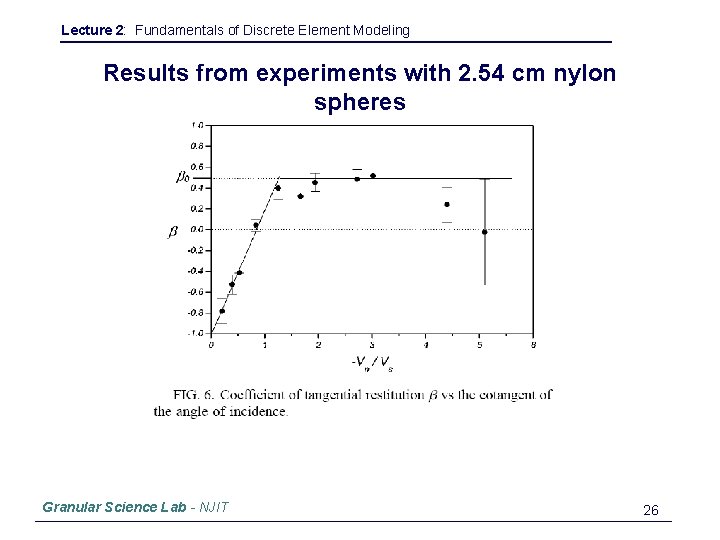

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Results from experiments with 2. 54 cm nylon spheres Granular Science Lab - NJIT 26

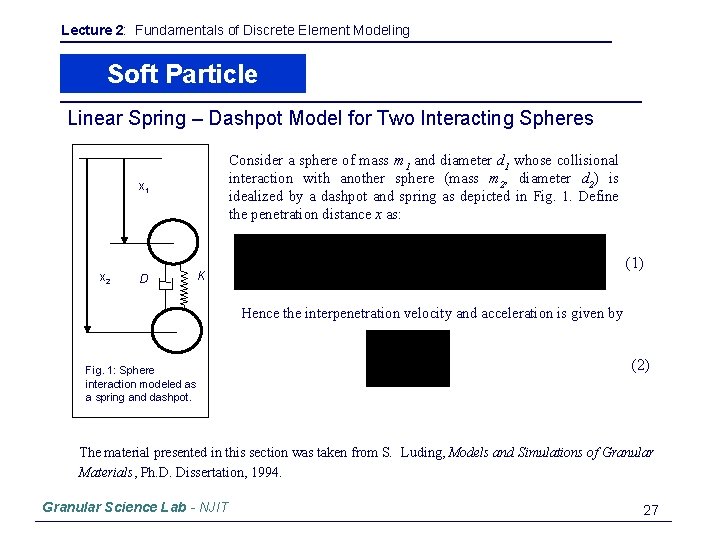

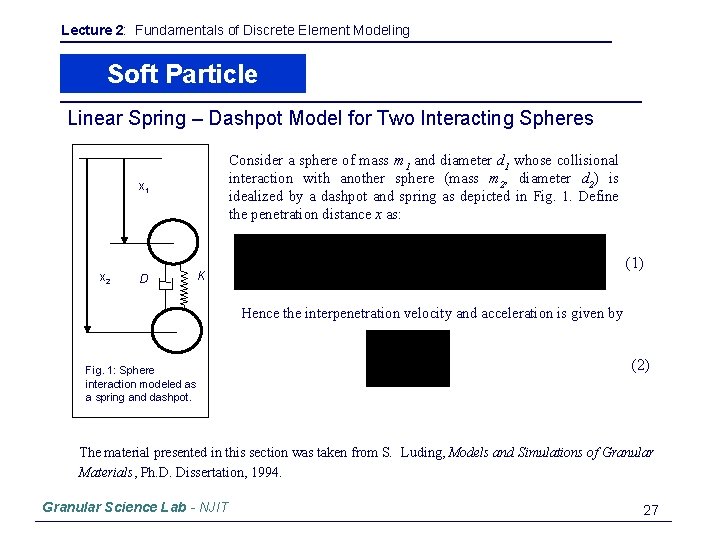

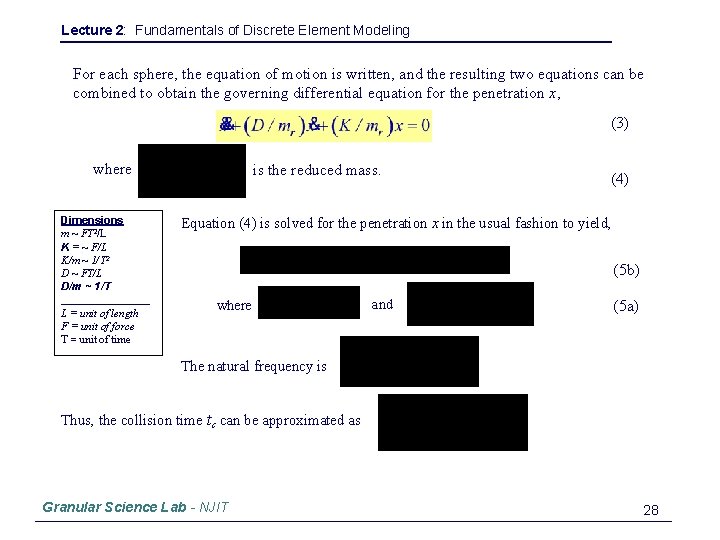

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Soft Particle Models Linear Spring – Dashpot Model for Two Interacting Spheres Consider a sphere of mass m 1 and diameter d 1 whose collisional interaction with another sphere (mass m 2, diameter d 2) is idealized by a dashpot and spring as depicted in Fig. 1. Define the penetration distance x as: x 1 x 2 D (1) K Hence the interpenetration velocity and acceleration is given by Fig. 1: Sphere interaction modeled as a spring and dashpot. (2) The material presented in this section was taken from S. Luding, Models and Simulations of Granular Materials, Ph. D. Dissertation, 1994. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 27

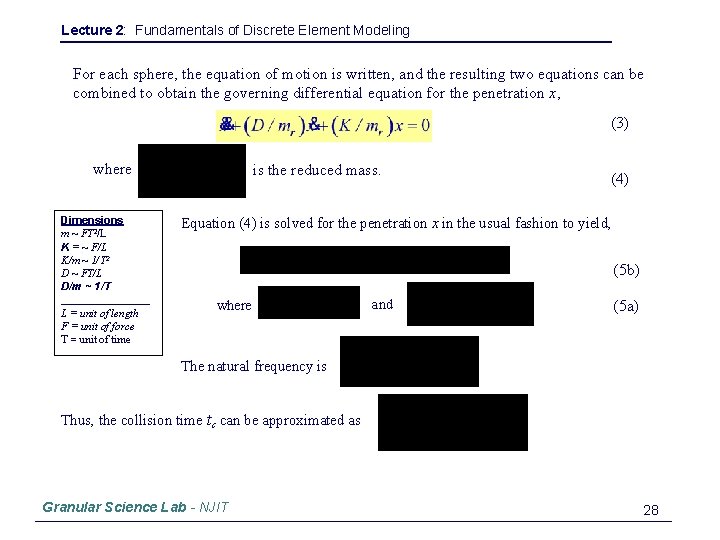

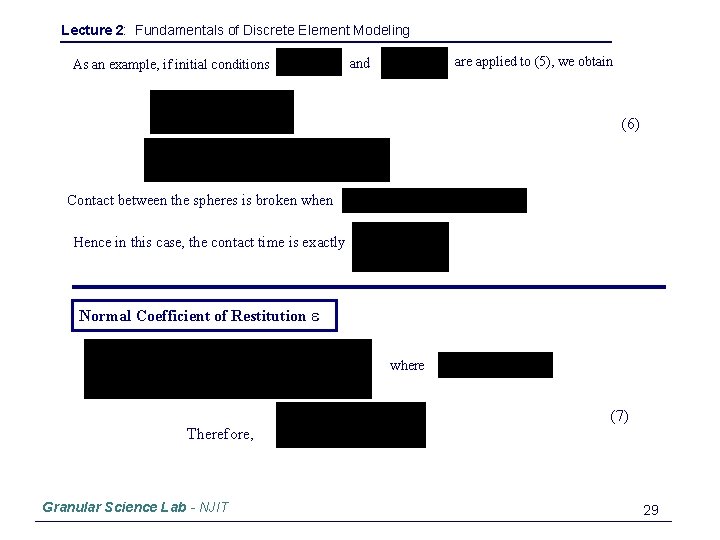

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling For each sphere, the equation of motion is written, and the resulting two equations can be combined to obtain the governing differential equation for the penetration x, (3) where Dimensions m ~ FT 2/L K = ~ F/L K/m ~ 1/T 2 D ~ FT/L D/m ~ 1/T ________ L = unit of length F = unit of force T = unit of time is the reduced mass. (4) Equation (4) is solved for the penetration x in the usual fashion to yield, (5 b) where and (5 a) The natural frequency is Thus, the collision time tc can be approximated as Granular Science Lab - NJIT 28

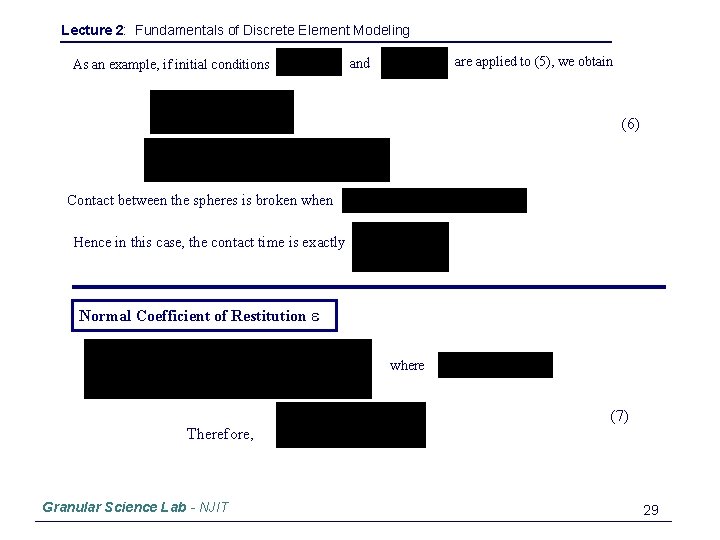

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling As an example, if initial conditions are applied to (5), we obtain and (6) Contact between the spheres is broken when Hence in this case, the contact time is exactly Normal Coefficient of Restitution e where Therefore, Granular Science Lab - NJIT (7) 29

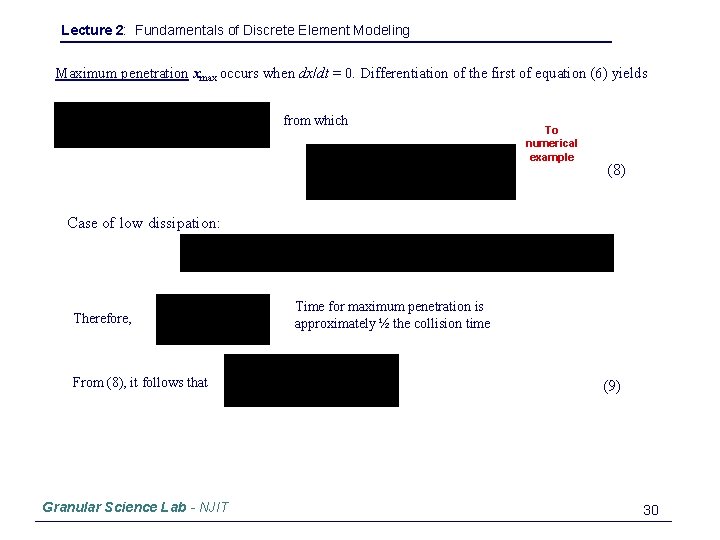

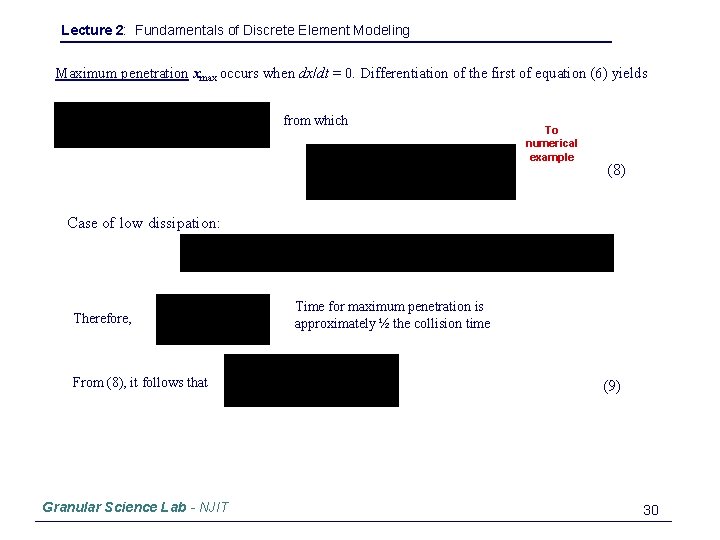

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Maximum penetration xmax occurs when dx/dt = 0. Differentiation of the first of equation (6) yields from which To numerical example (8) Case of low dissipation: Therefore, From (8), it follows that Granular Science Lab - NJIT Time for maximum penetration is approximately ½ the collision time (9) 30

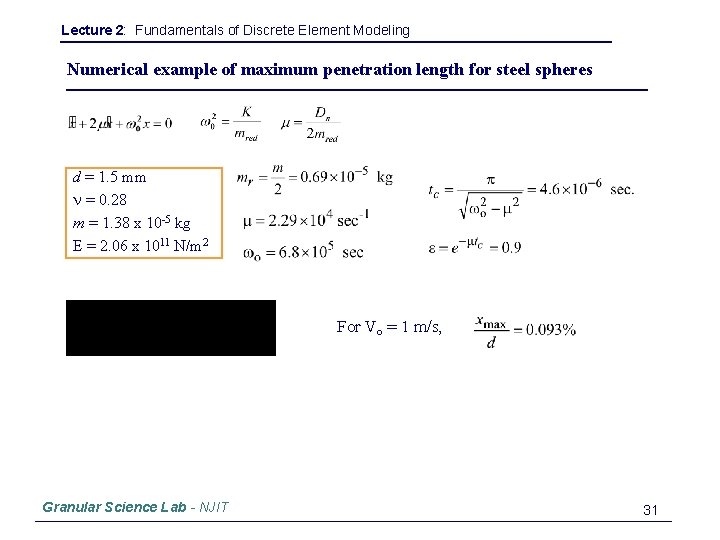

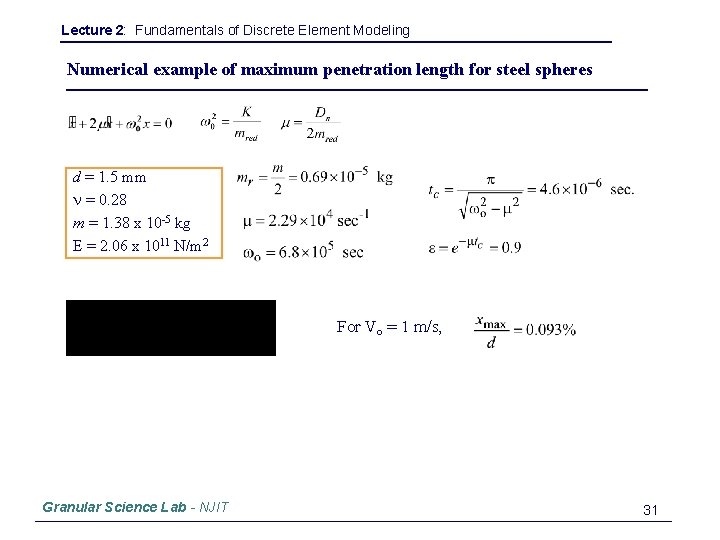

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Numerical example of maximum penetration length for steel spheres d = 1. 5 mm n = 0. 28 m = 1. 38 x 10 -5 kg E = 2. 06 x 1011 N/m 2 For Vo = 1 m/s, Granular Science Lab - NJIT 31

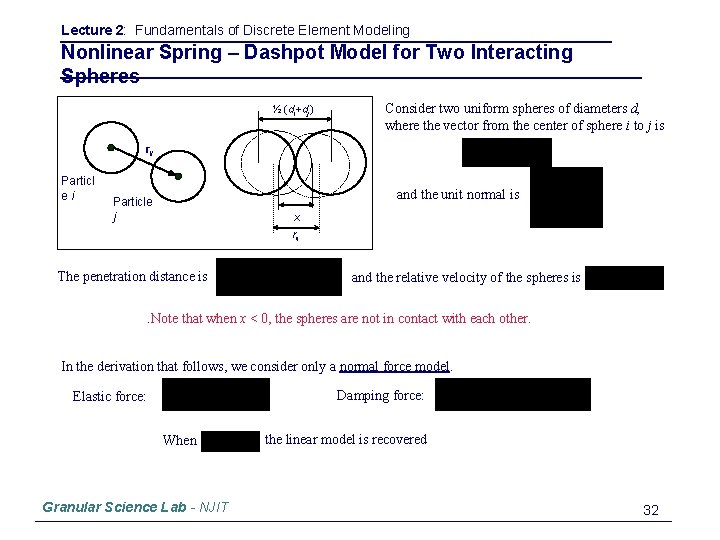

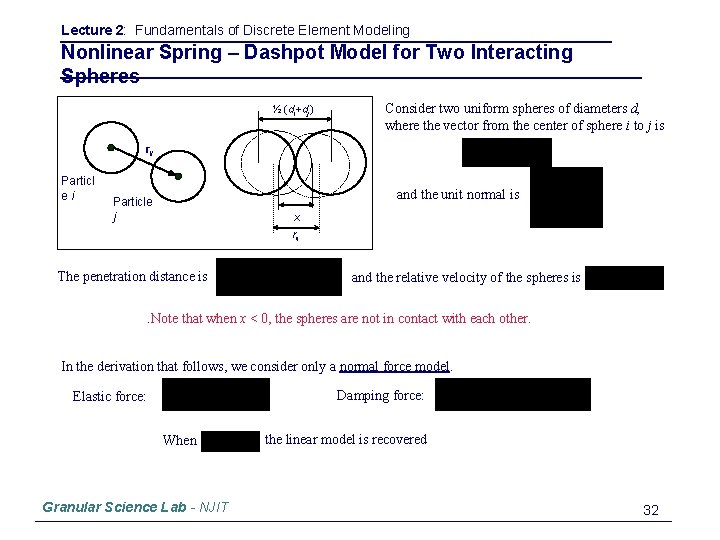

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Nonlinear Spring – Dashpot Model for Two Interacting Spheres ½ (di+dj) Consider two uniform spheres of diameters d, where the vector from the center of sphere i to j is rij Particl ei and the unit normal is Particle j x rij The penetration distance is. Note and the relative velocity of the spheres is that when x < 0, the spheres are not in contact with each other. In the derivation that follows, we consider only a normal force model. Damping force: Elastic force: When Granular Science Lab - NJIT the linear model is recovered 32

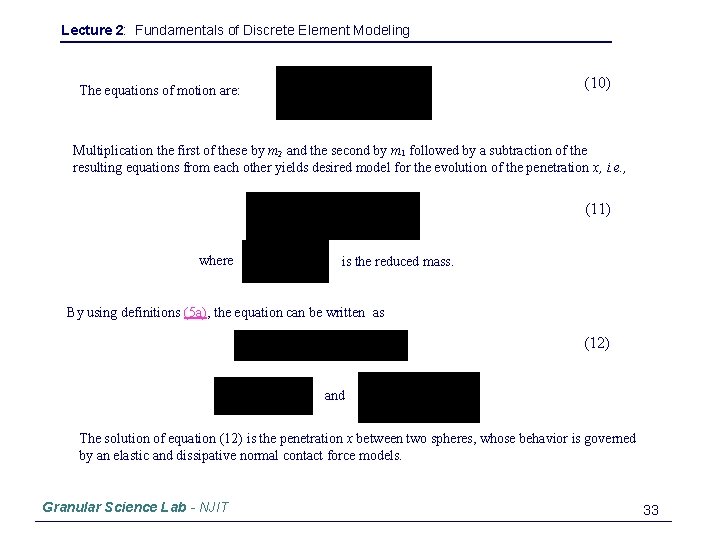

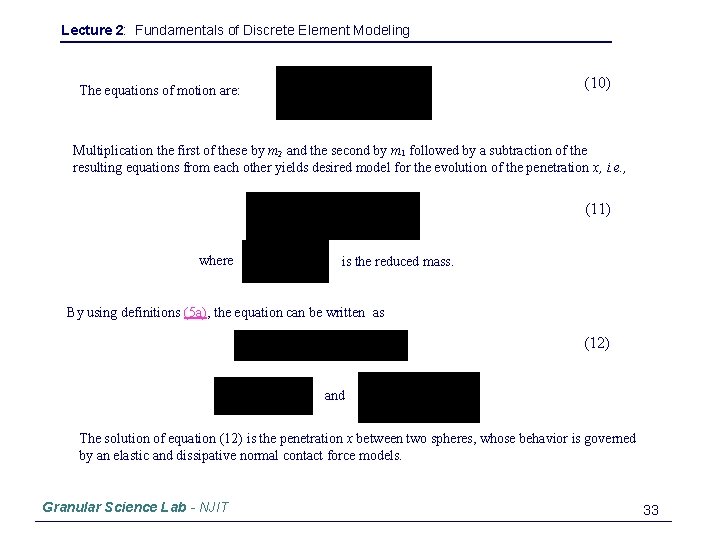

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling (10) The equations of motion are: Multiplication the first of these by m 2 and the second by m 1 followed by a subtraction of the resulting equations from each other yields desired model for the evolution of the penetration x, i. e. , (11) where is the reduced mass. By using definitions (5 a), the equation can be written as (12) and The solution of equation (12) is the penetration x between two spheres, whose behavior is governed by an elastic and dissipative normal contact force models. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 33

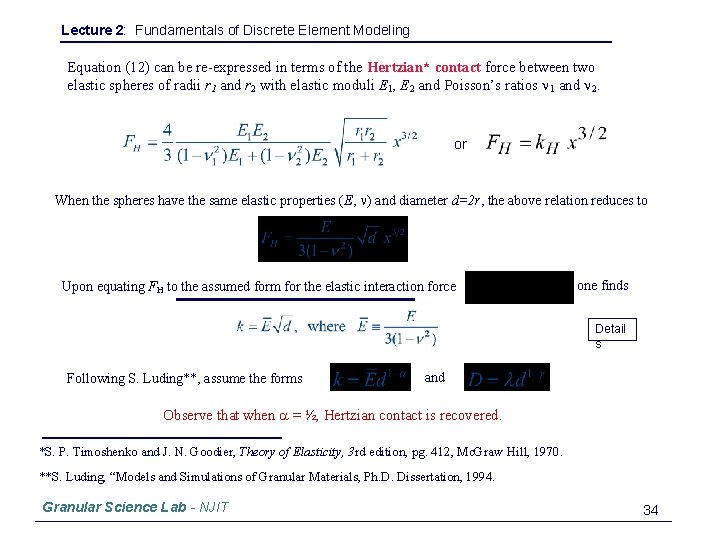

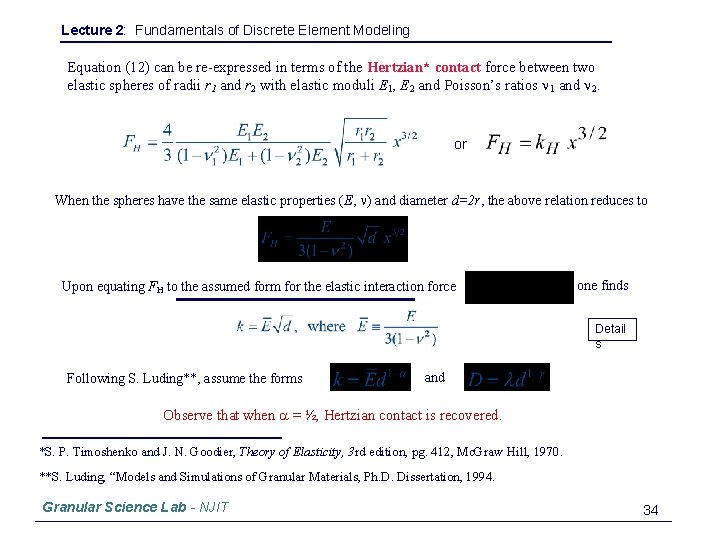

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Equation (12) can be re-expressed in terms of the Hertzian* contact force between two elastic spheres of radii r 1 and r 2 with elastic moduli E 1, E 2 and Poisson’s ratios n 1 and n 2. or When the spheres have the same elastic properties (E, n) and diameter d=2 r, the above relation reduces to Upon equating FH to the assumed form for the elastic interaction force one finds Detail s Following S. Luding**, assume the forms and Observe that when a = ½, Hertzian contact is recovered. *S. P. Timoshenko and J. N. Goodier, Theory of Elasticity, 3 rd edition, pg. 412, Mc. Graw Hill, 1970. **S. Luding, “Models and Simulations of Granular Materials, Ph. D. Dissertation, 1994. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 34

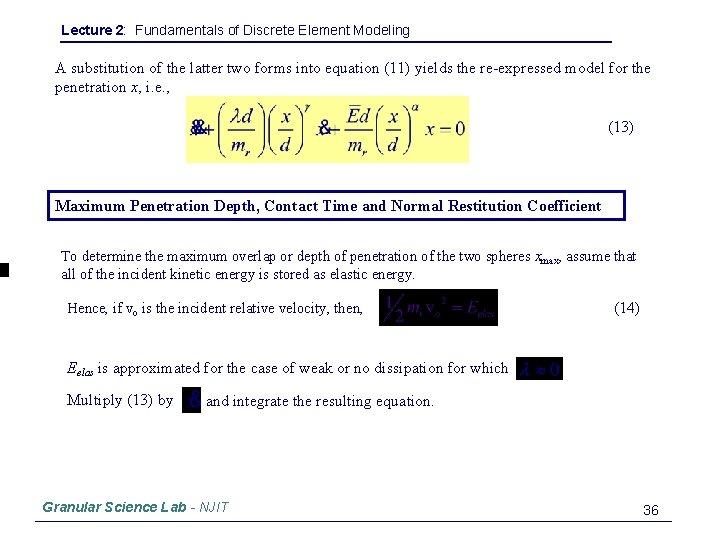

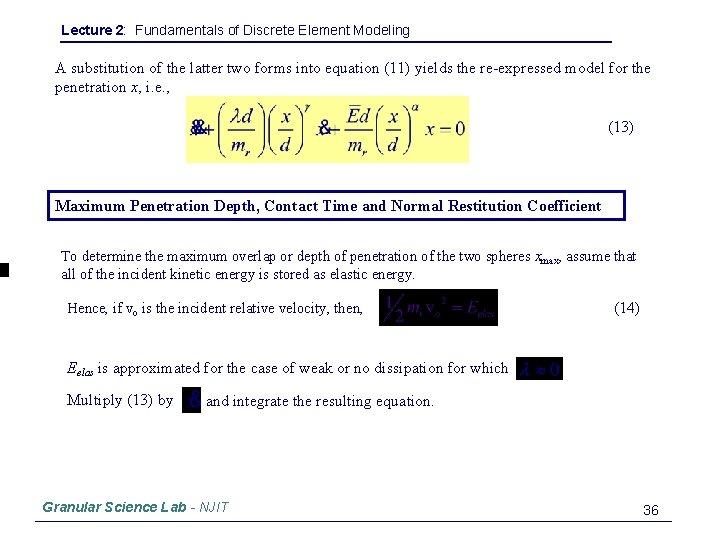

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling A substitution of the latter two forms into equation (11) yields the re-expressed model for the penetration x, i. e. , (13) Maximum Penetration Depth, Contact Time and Normal Restitution Coefficient To determine the maximum overlap or depth of penetration of the two spheres xmax, assume that all of the incident kinetic energy is stored as elastic energy. Hence, if vo is the incident relative velocity, then, (14) Eelas is approximated for the case of weak or no dissipation for which Multiply (13) by and integrate the resulting equation. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 36

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling (15) A substitution of (15) into (14) yields the maximum penetration, (16) The contact time tc can be estimated from energy conservation (i. e. , little or no dissipation) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 37

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling This latter expression is simplified using the beta function* to produce the result… (17 a) (17 b) Reduction to Hertzian model when a = ½: (18) Normal Coefficient of Restitution The coefficient of restitution can be determined from the energy dissipated in a collision where (19) *Abramowitz & Stegun, Handbook of Mathematical Functions, pg. 258, Dover, 1972. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 38

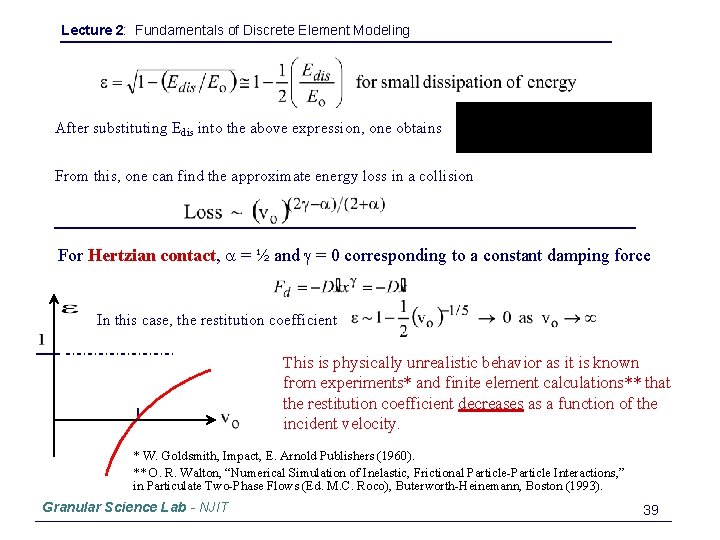

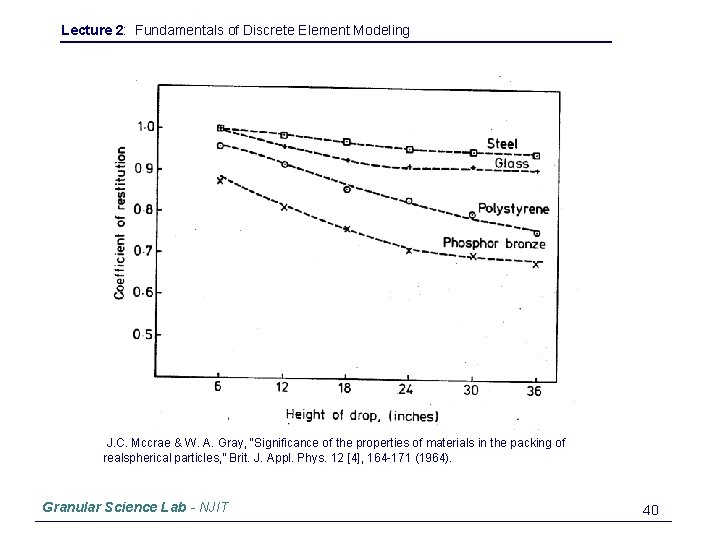

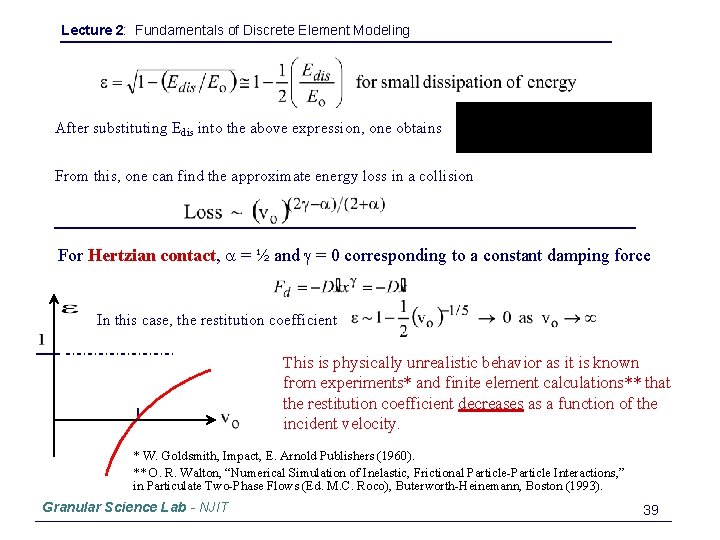

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling After substituting Edis into the above expression, one obtains From this, one can find the approximate energy loss in a collision For Hertzian contact, a = ½ and g = 0 corresponding to a constant damping force In this case, the restitution coefficient This is physically unrealistic behavior as it is known from experiments* and finite element calculations** that the restitution coefficient decreases as a function of the incident velocity. * W. Goldsmith, Impact, E. Arnold Publishers (1960). ** O. R. Walton, “Numerical Simulation of Inelastic, Frictional Particle-Particle Interactions, ” in Particulate Two-Phase Flows (Ed. M. C. Roco), Buterworth-Heinemann, Boston (1993). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 39

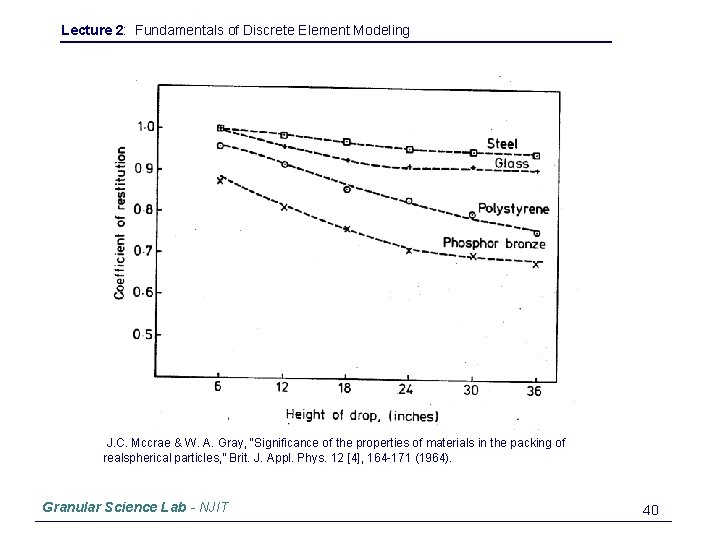

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling J. C. Mccrae & W. A. Gray, “Significance of the properties of materials in the packing of realspherical particles, ” Brit. J. Appl. Phys. 12 [4], 164 -171 (1964). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 40

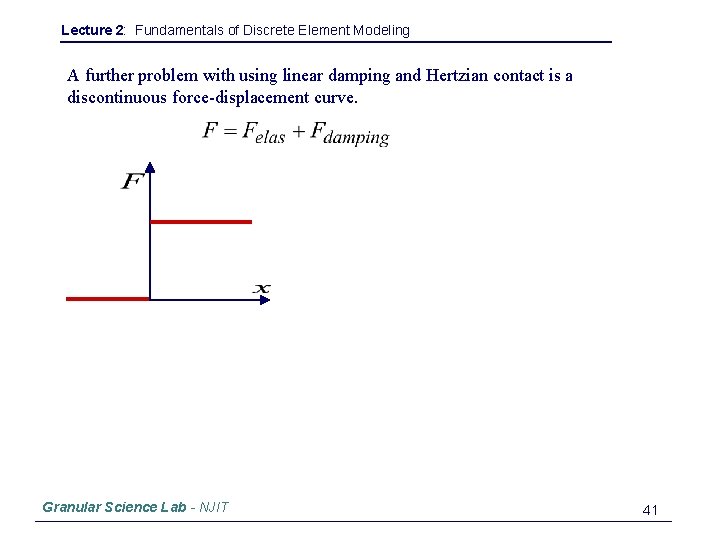

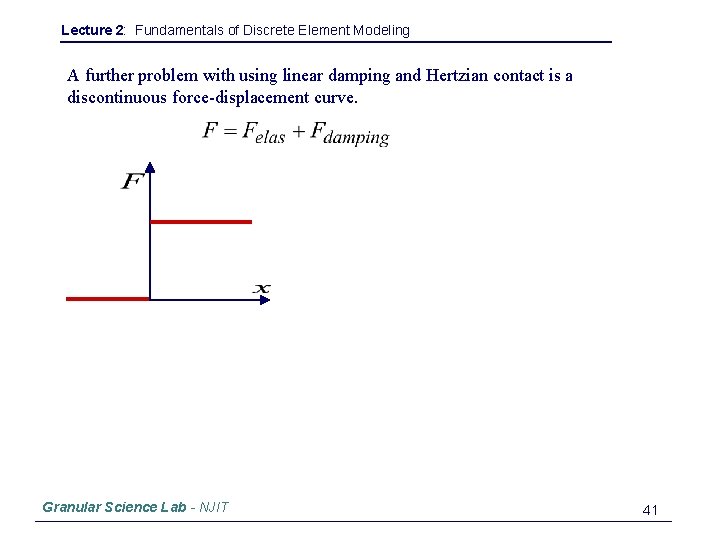

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling A further problem with using linear damping and Hertzian contact is a discontinuous force-displacement curve. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 41

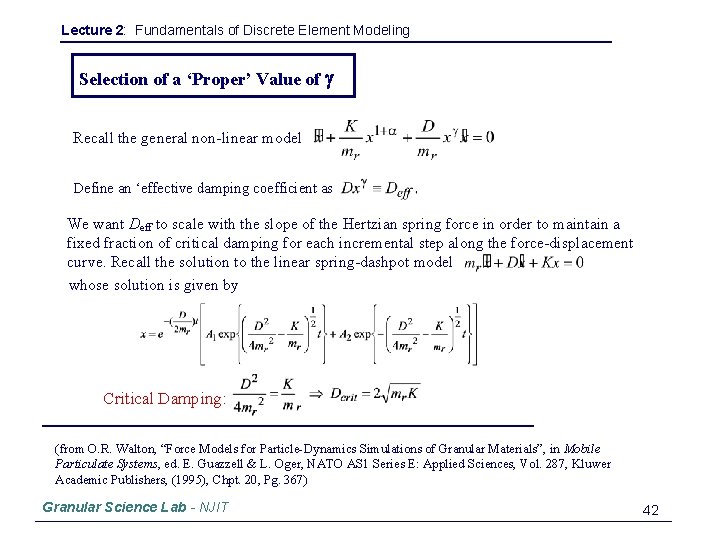

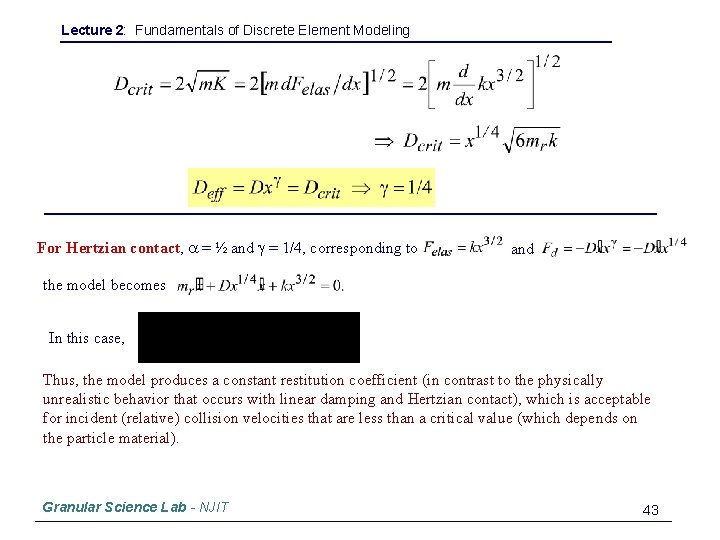

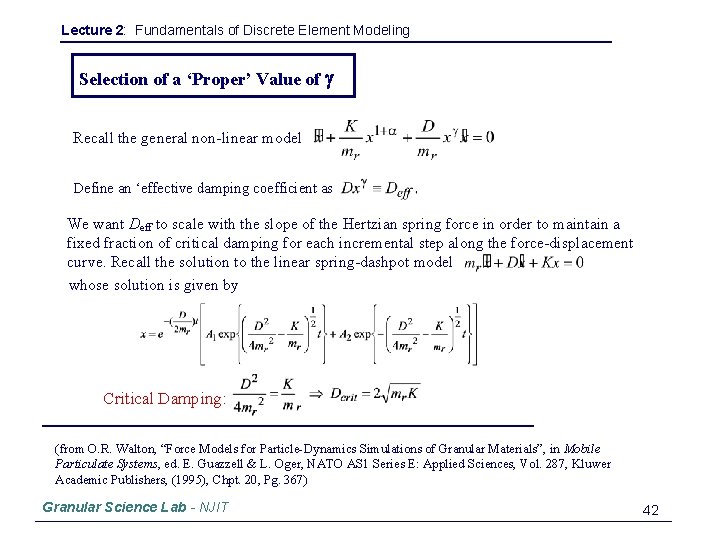

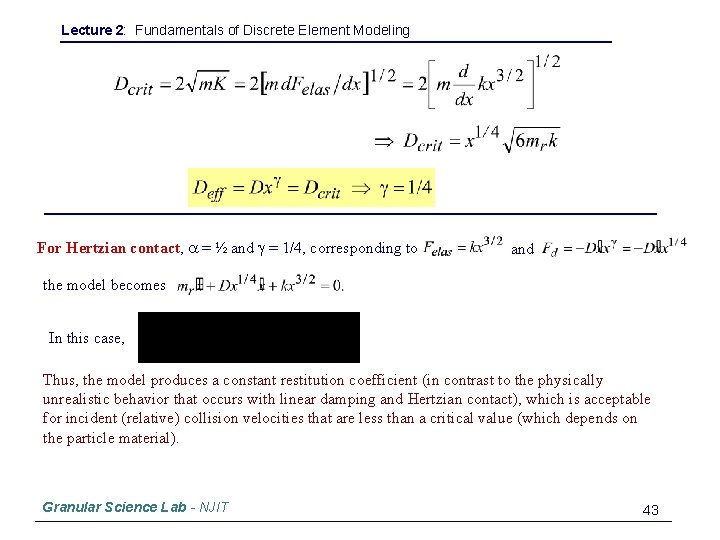

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Selection of a ‘Proper’ Value of g Recall the general non-linear model Define an ‘effective damping coefficient as We want Deff to scale with the slope of the Hertzian spring force in order to maintain a fixed fraction of critical damping for each incremental step along the force-displacement curve. Recall the solution to the linear spring-dashpot model whose solution is given by Critical Damping: (from O. R. Walton, “Force Models for Particle-Dynamics Simulations of Granular Materials”, in Mobile Particulate Systems, ed. E. Guazzell & L. Oger, NATO AS 1 Series E: Applied Sciences, Vol. 287, Kluwer Academic Publishers, (1995), Chpt. 20, Pg. 367) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 42

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling For Hertzian contact, a = ½ and g = 1/4, corresponding to and the model becomes In this case, Thus, the model produces a constant restitution coefficient (in contrast to the physically unrealistic behavior that occurs with linear damping and Hertzian contact), which is acceptable for incident (relative) collision velocities that are less than a critical value (which depends on the particle material). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 43

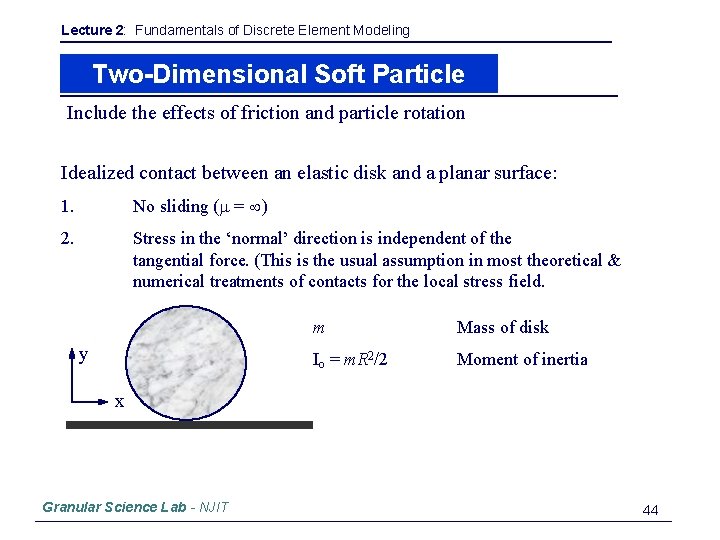

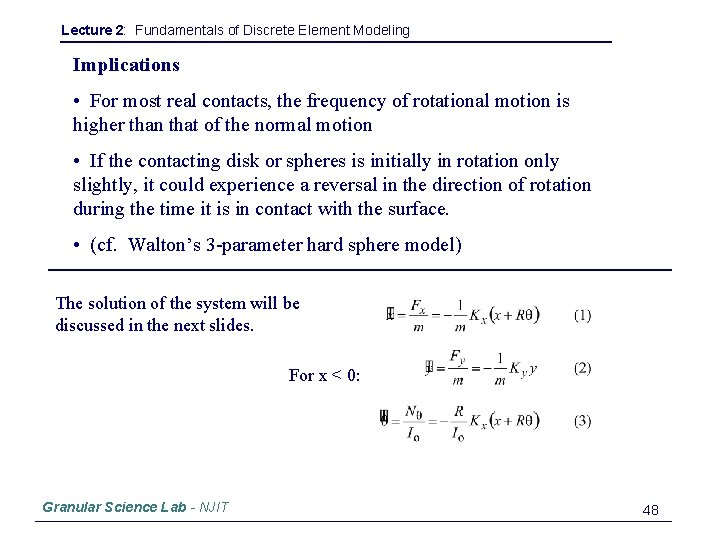

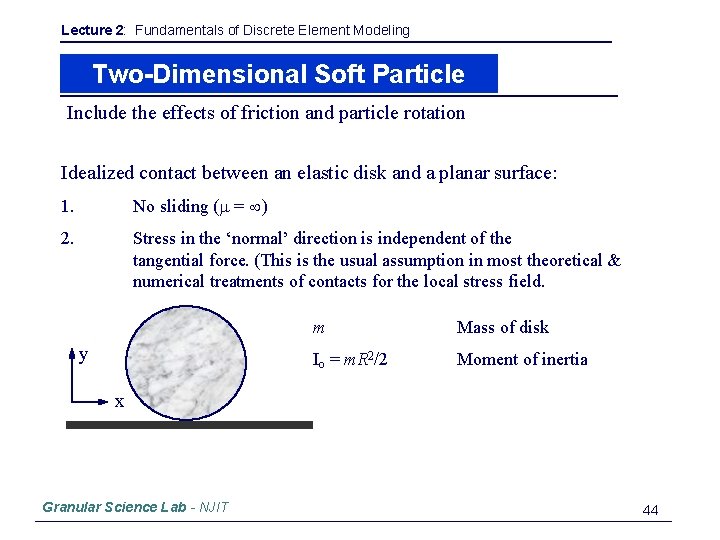

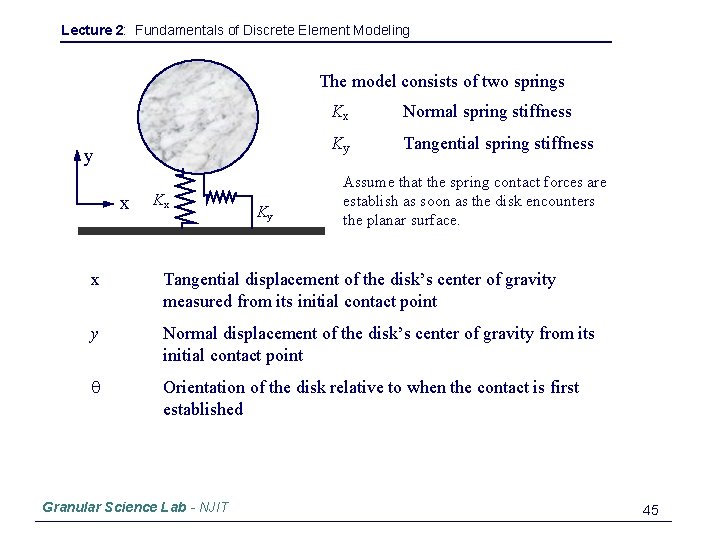

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Two-Dimensional Soft Particle Include the effects of. Models friction and particle rotation Idealized contact between an elastic disk and a planar surface: 1. No sliding (m = ) 2. Stress in the ‘normal’ direction is independent of the tangential force. (This is the usual assumption in most theoretical & numerical treatments of contacts for the local stress field. y m Mass of disk Io = m. R 2/2 Moment of inertia x Granular Science Lab - NJIT 44

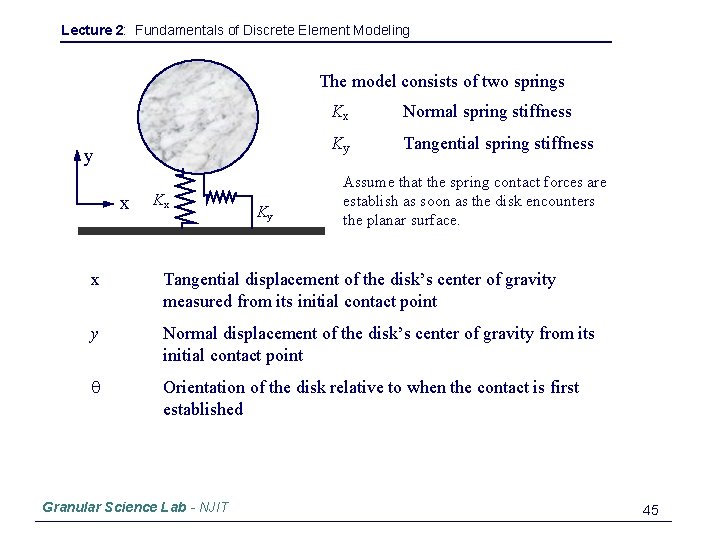

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling The model consists of two springs y x Kx Ky Kx Normal spring stiffness Ky Tangential spring stiffness Assume that the spring contact forces are establish as soon as the disk encounters the planar surface. x Tangential displacement of the disk’s center of gravity measured from its initial contact point y Normal displacement of the disk’s center of gravity from its initial contact point q Orientation of the disk relative to when the contact is first established Granular Science Lab - NJIT 45

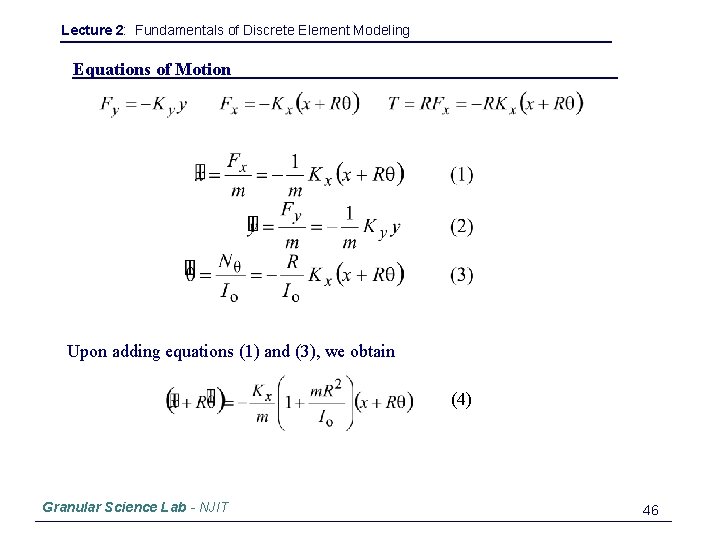

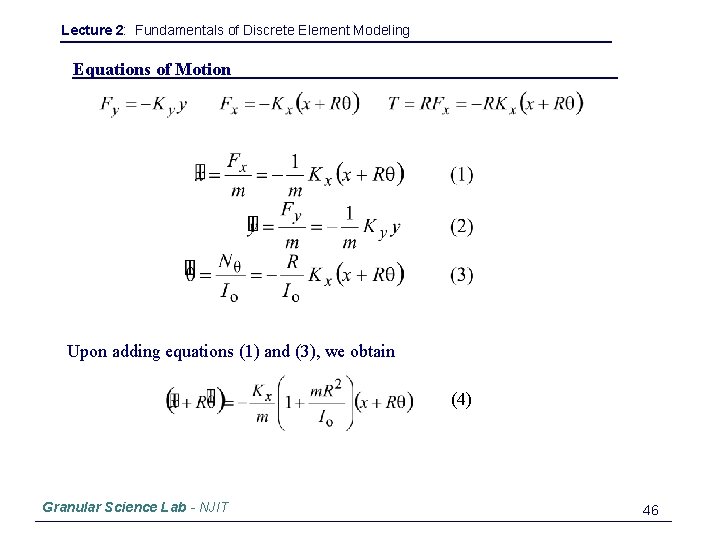

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Equations of Motion Upon adding equations (1) and (3), we obtain (4) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 46

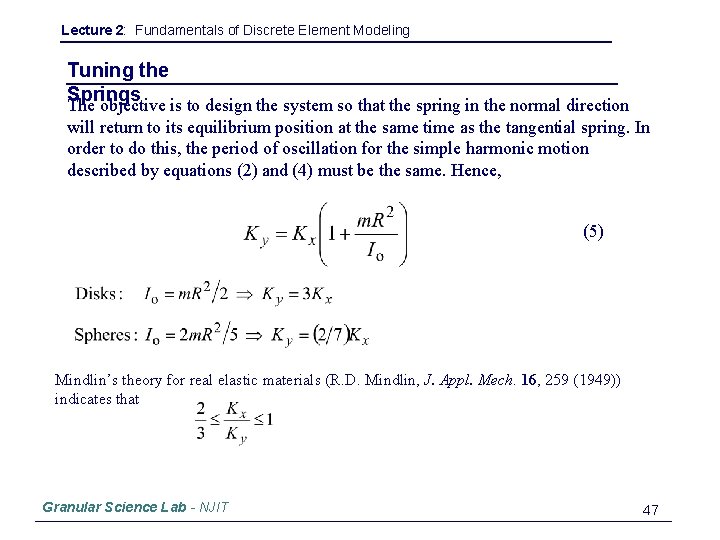

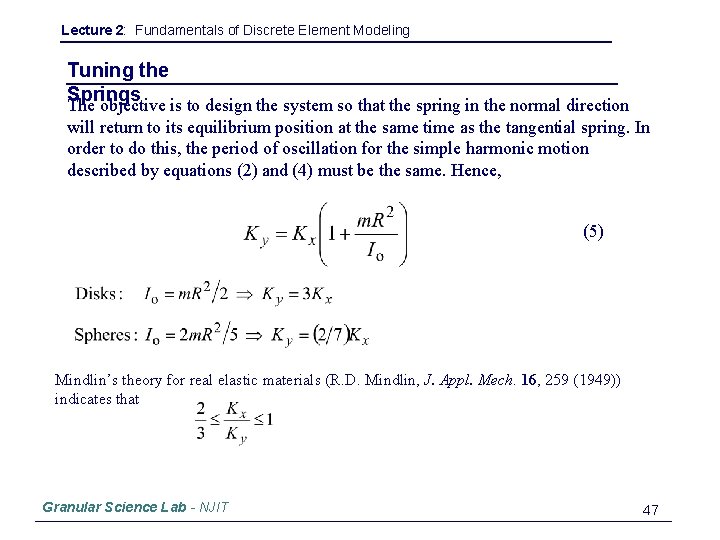

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Tuning the Springs The objective is to design the system so that the spring in the normal direction will return to its equilibrium position at the same time as the tangential spring. In order to do this, the period of oscillation for the simple harmonic motion described by equations (2) and (4) must be the same. Hence, (5) Mindlin’s theory for real elastic materials (R. D. Mindlin, J. Appl. Mech. 16, 259 (1949)) indicates that Granular Science Lab - NJIT 47

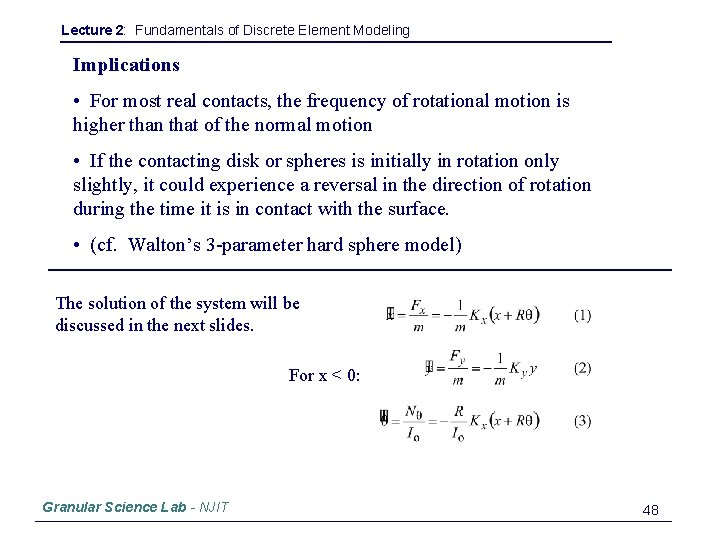

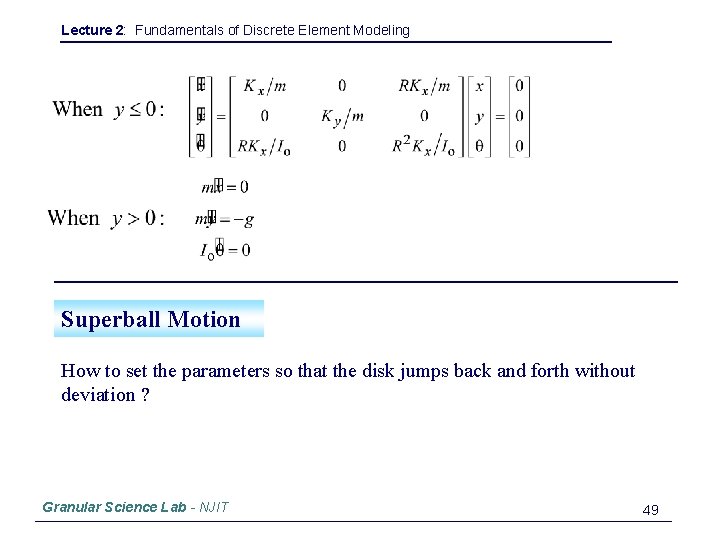

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Implications • For most real contacts, the frequency of rotational motion is higher than that of the normal motion • If the contacting disk or spheres is initially in rotation only slightly, it could experience a reversal in the direction of rotation during the time it is in contact with the surface. • (cf. Walton’s 3 -parameter hard sphere model) The solution of the system will be discussed in the next slides. For x < 0: Granular Science Lab - NJIT 48

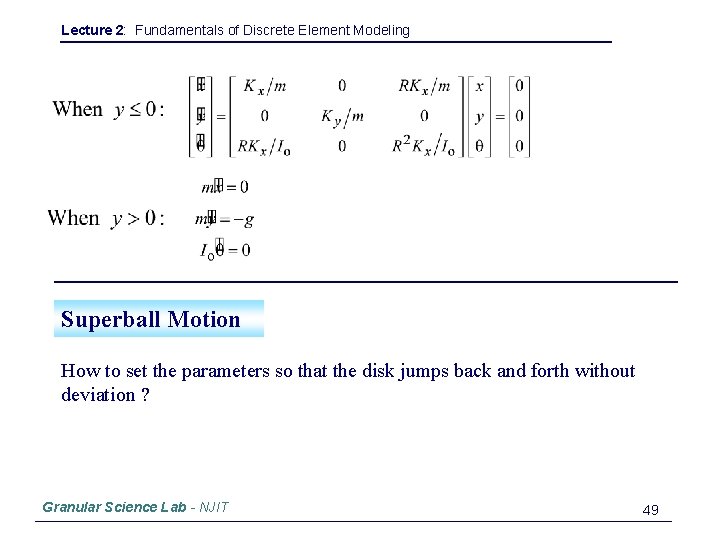

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Superball Motion How to set the parameters so that the disk jumps back and forth without deviation ? Granular Science Lab - NJIT 49

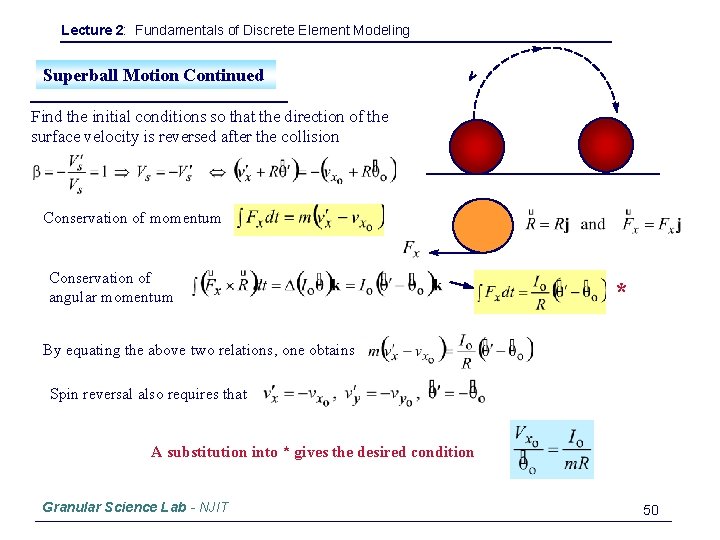

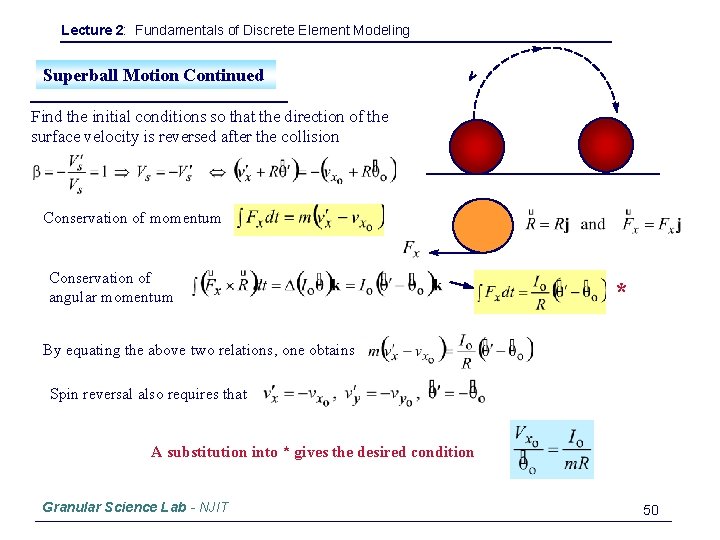

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Superball Motion Continued Find the initial conditions so that the direction of the surface velocity is reversed after the collision Conservation of momentum Conservation of angular momentum * By equating the above two relations, one obtains Spin reversal also requires that A substitution into * gives the desired condition Granular Science Lab - NJIT 50

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Implementation of Superball Model Superball. Exe Copyrighted application by Y. Chung Granular Science Lab - NJIT 51

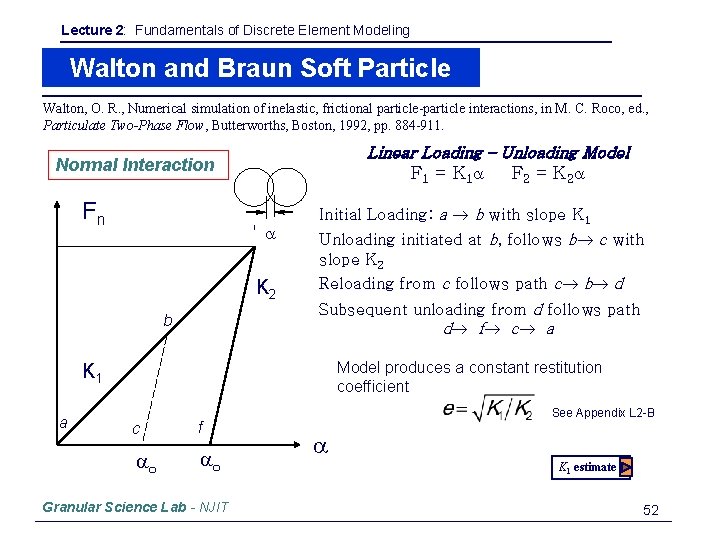

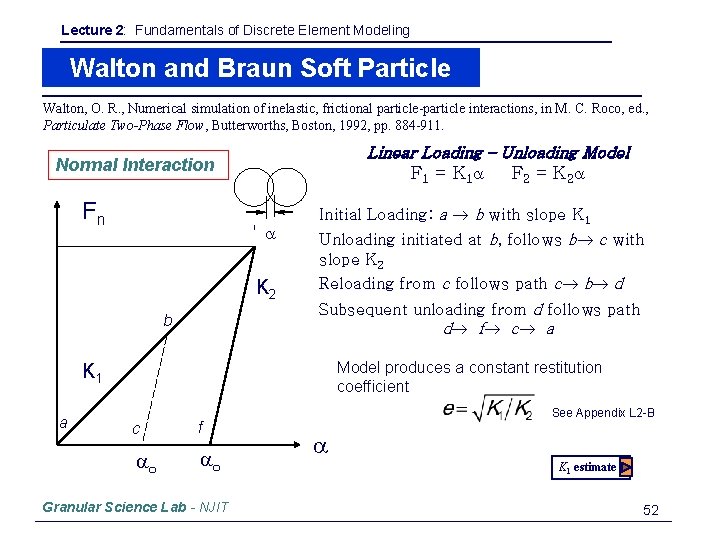

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Walton and Braun Soft Particle Models Walton, O. R. , Numerical simulation of inelastic, frictional particle-particle interactions, in M. C. Roco, ed. , Particulate Two-Phase Flow, Butterworths, Boston, 1992, pp. 884 -911. Linear Loading – Unloading Model Normal Interaction Fn F 1 = K 1 a da K 2 b Initial Loading: a b with slope K 1 Unloading initiated at b, follows b c with slope K 2 Reloading from c follows path c b d Subsequent unloading from d follows path d f c a Model produces a constant restitution coefficient K 1 a F 2 = K 2 a c f ao ao Granular Science Lab - NJIT See Appendix L 2 -B a K 1 estimate 52

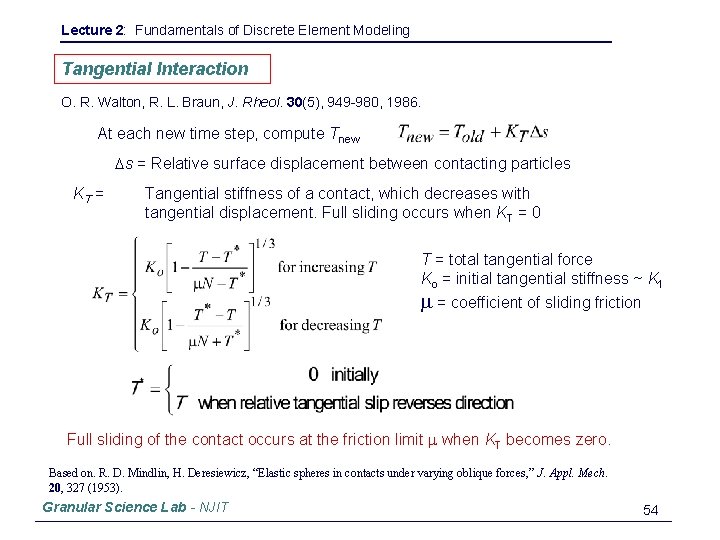

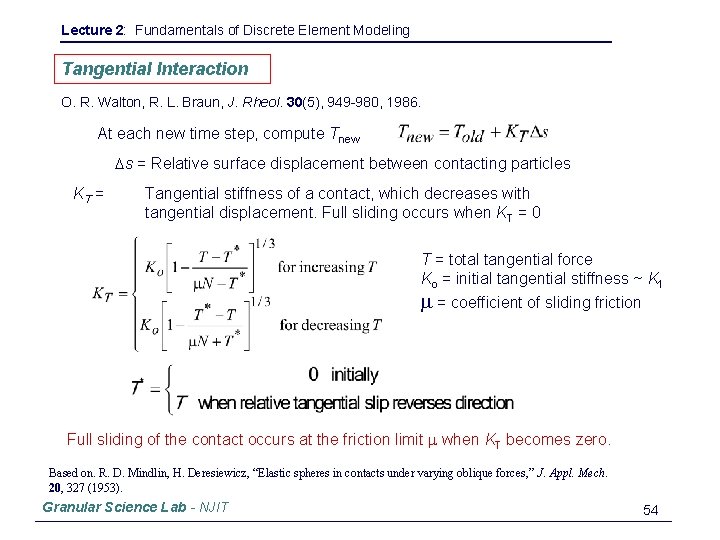

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Tangential Interaction O. R. Walton, R. L. Braun, J. Rheol. 30(5), 949 -980, 1986. At each new time step, compute Tnew s = Relative surface displacement between contacting particles KT = Tangential stiffness of a contact, which decreases with tangential displacement. Full sliding occurs when KT = 0 T = total tangential force Ko = initial tangential stiffness ~ K 1 m = coefficient of sliding friction Full sliding of the contact occurs at the friction limit m when KT becomes zero. Based on. R. D. Mindlin, H. Deresiewicz, “Elastic spheres in contacts under varying oblique forces, ” J. Appl. Mech. 20, 327 (1953). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 54

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Notes taken from O. R. Walton, “Force Models for Particle-Dynamics Simulations of Granular Materials, ” in Mobile Particulate Systems (eds. E. Guazzelli & L. Oger), NATO ASI Series (Series E: Applied Sciences), Vol. 287, pp. 370 (1994). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 55

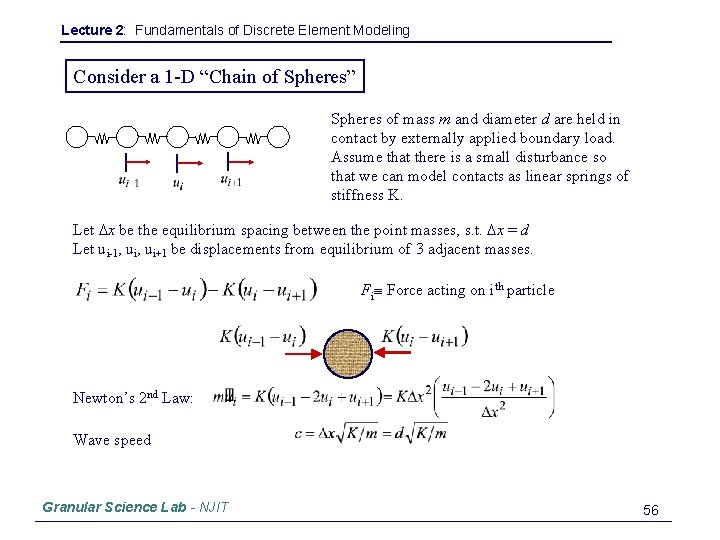

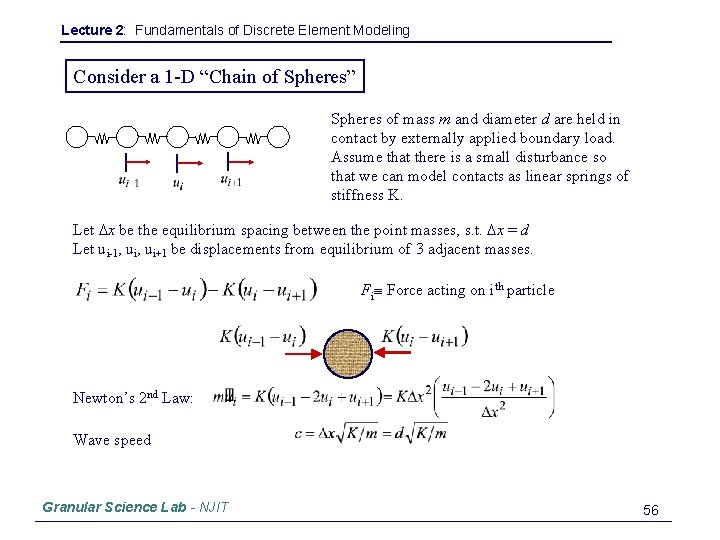

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Consider a 1 -D “Chain of Spheres” Spheres of mass m and diameter d are held in contact by externally applied boundary load. Assume that there is a small disturbance so that we can model contacts as linear springs of stiffness K. Let x be the equilibrium spacing between the point masses, s. t. x = d Let ui-1, ui+1 be displacements from equilibrium of 3 adjacent masses. Fi Force acting on ith particle Newton’s 2 nd Law: Wave speed Granular Science Lab - NJIT 56

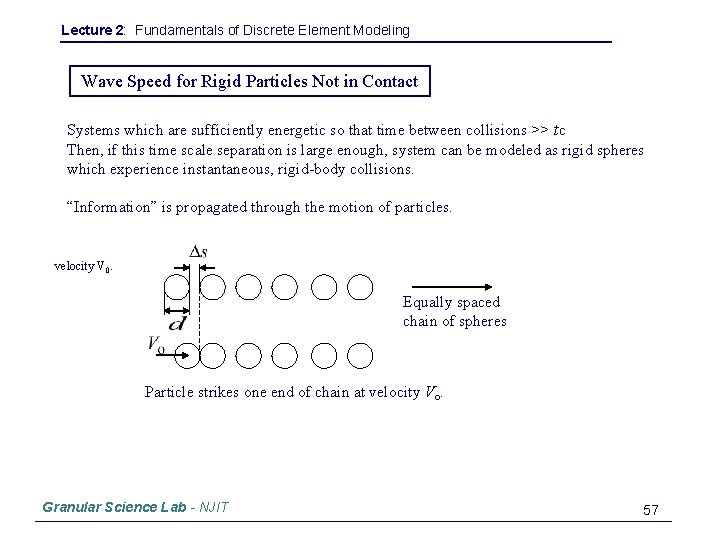

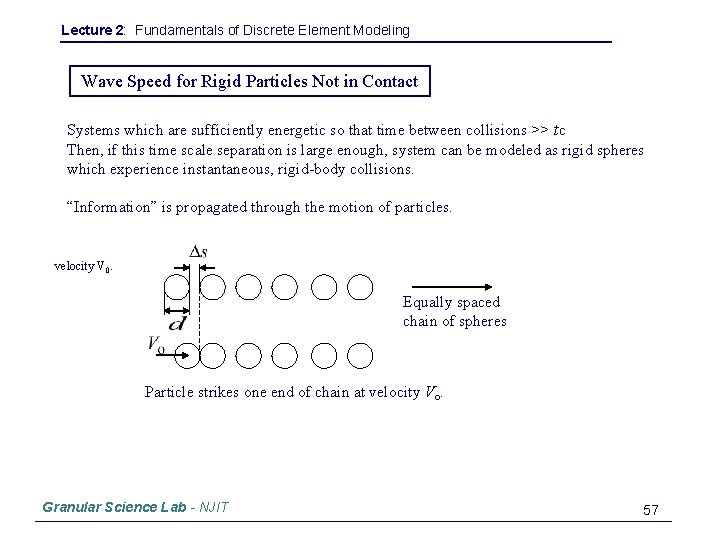

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Wave Speed for Rigid Particles Not in Contact Systems which are sufficiently energetic so that time between collisions >> tc Then, if this time scale separation is large enough, system can be modeled as rigid spheres which experience instantaneous, rigid-body collisions. “Information” is propagated through the motion of particles. velocity V 0. Equally spaced chain of spheres Particle strikes one end of chain at velocity Vo. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 57

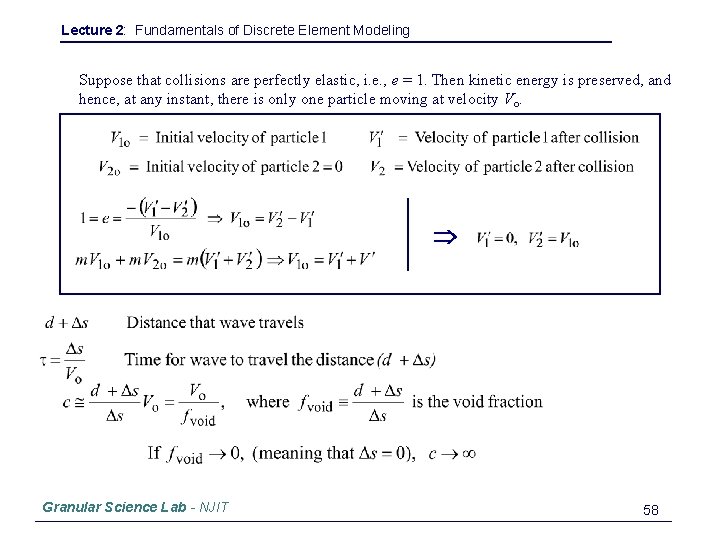

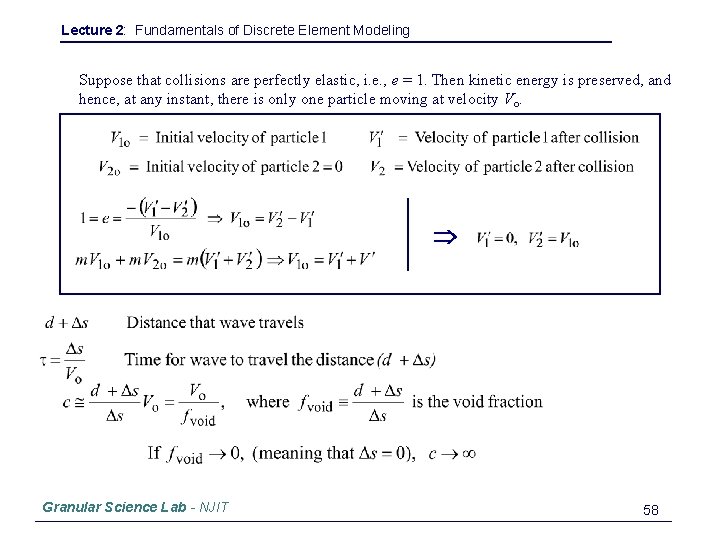

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Suppose that collisions are perfectly elastic, i. e. , e = 1. Then kinetic energy is preserved, and hence, at any instant, there is only one particle moving at velocity Vo. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 58

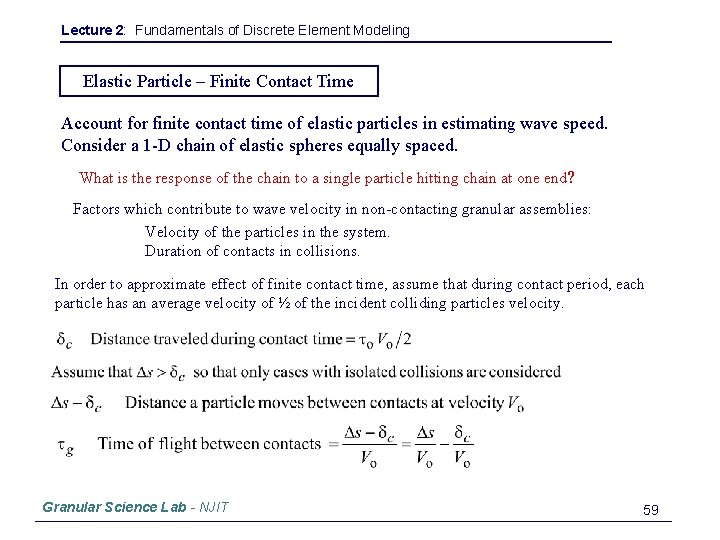

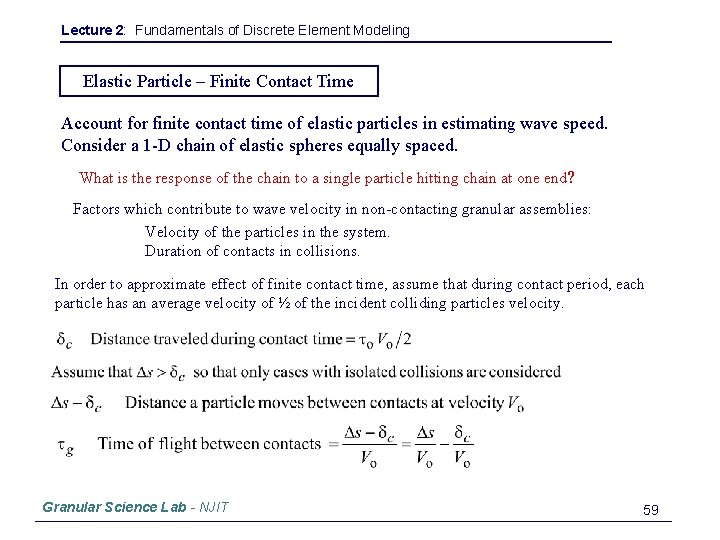

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Elastic Particle – Finite Contact Time Account for finite contact time of elastic particles in estimating wave speed. Consider a 1 -D chain of elastic spheres equally spaced. What is the response of the chain to a single particle hitting chain at one end ? Factors which contribute to wave velocity in non-contacting granular assemblies: Velocity of the particles in the system. Duration of contacts in collisions. In order to approximate effect of finite contact time, assume that during contact period, each particle has an average velocity of ½ of the incident colliding particles velocity. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 59

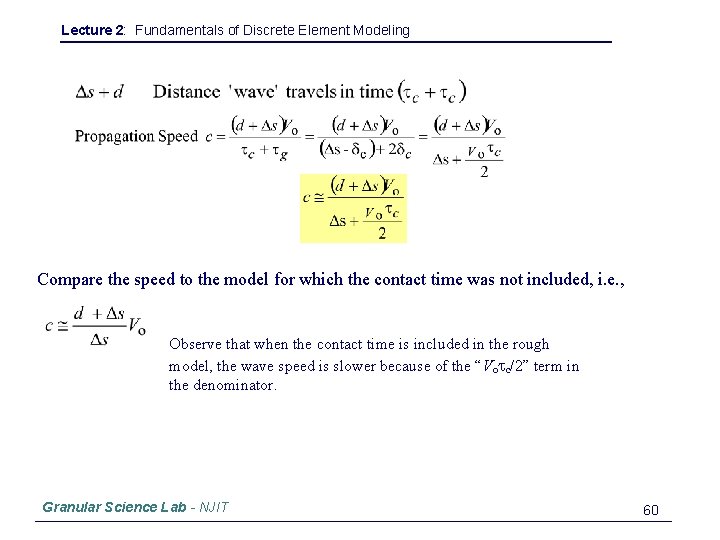

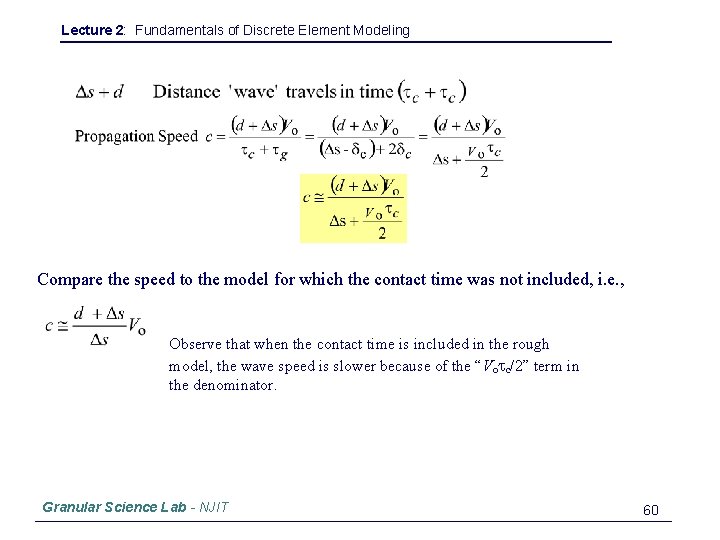

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Compare the speed to the model for which the contact time was not included, i. e. , Observe that when the contact time is included in the rough model, the wave speed is slower because of the “Votc/2” term in the denominator. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 60

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Material taken from K. Johnson, Contact Mechanics, Chapter 11, Cambridge University Press (1985). Granular Science Lab - NJIT 61

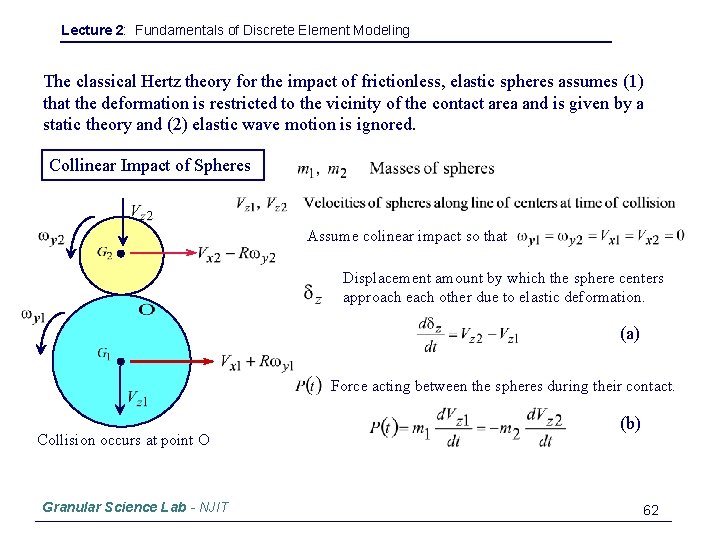

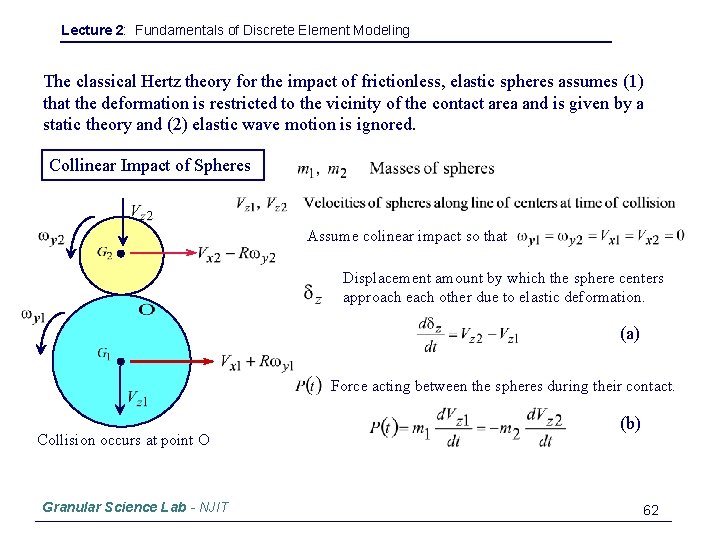

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling The classical Hertz theory for the impact of frictionless, elastic spheres assumes (1) that the deformation is restricted to the vicinity of the contact area and is given by a static theory and (2) elastic wave motion is ignored. Collinear Impact of Spheres Assume colinear impact so that Displacement amount by which the sphere centers approach each other due to elastic deformation. (a) Force acting between the spheres during their contact. Collision occurs at point O Granular Science Lab - NJIT (b) 62

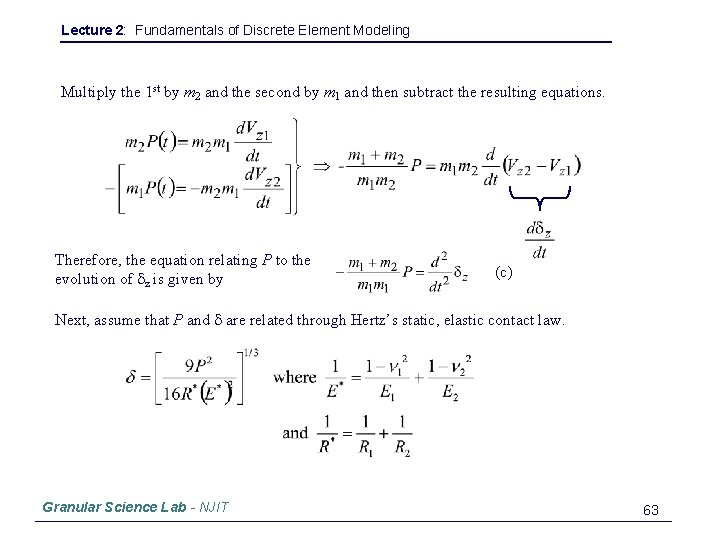

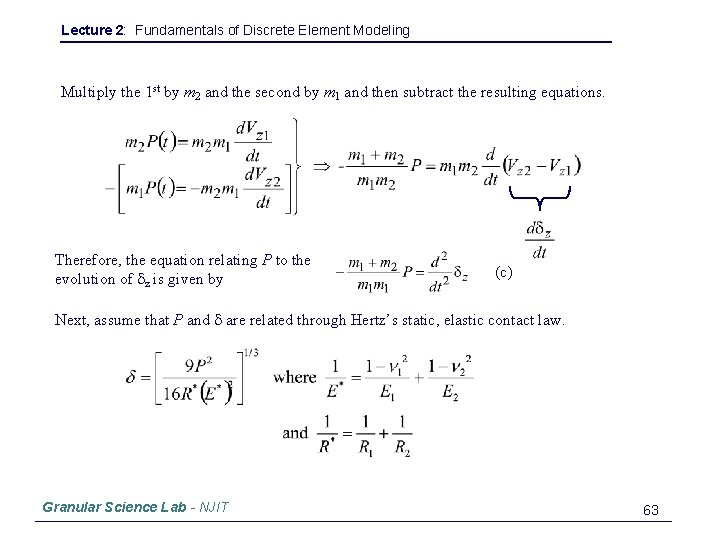

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Multiply the 1 st by m 2 and the second by m 1 and then subtract the resulting equations. Therefore, the equation relating P to the evolution of dz is given by (c) Next, assume that P and d are related through Hertz’s static, elastic contact law. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 63

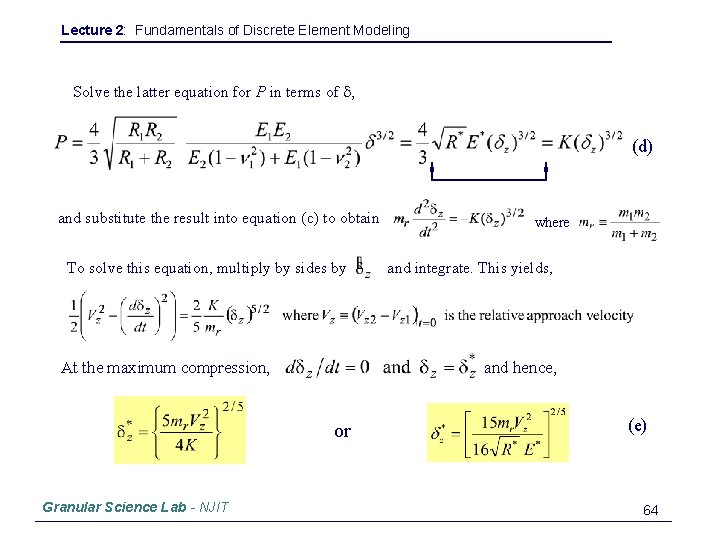

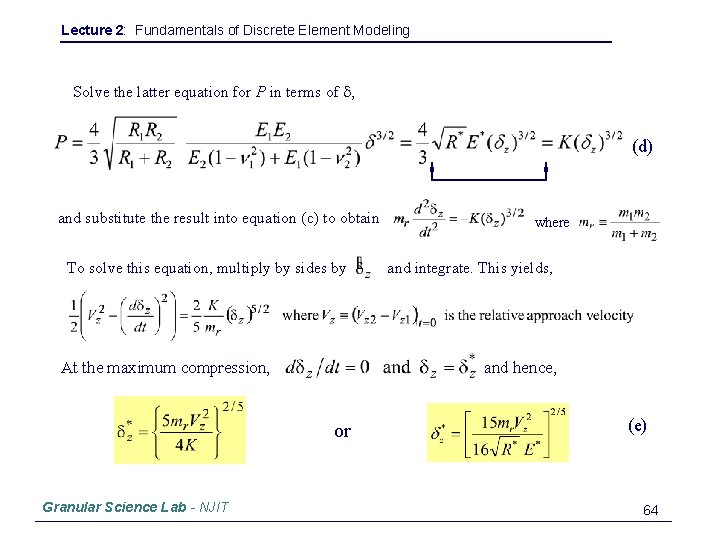

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Solve the latter equation for P in terms of d, (d) and substitute the result into equation (c) to obtain To solve this equation, multiply by sides by At the maximum compression, and integrate. This yields, and hence, or Granular Science Lab - NJIT where (e) 64

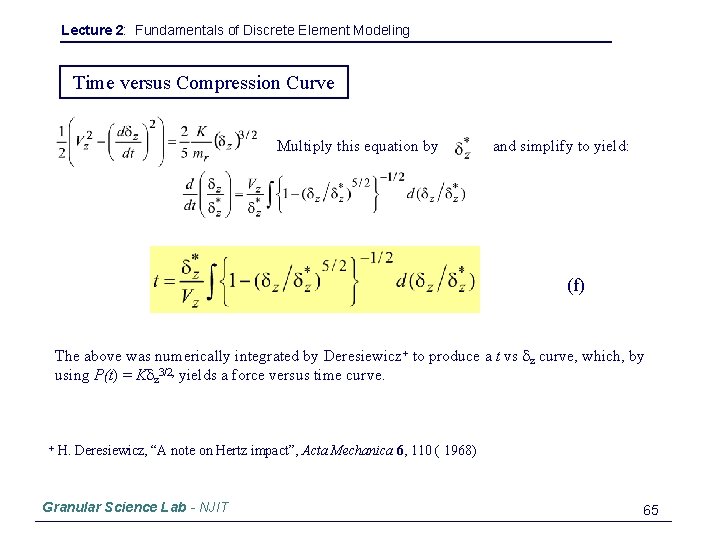

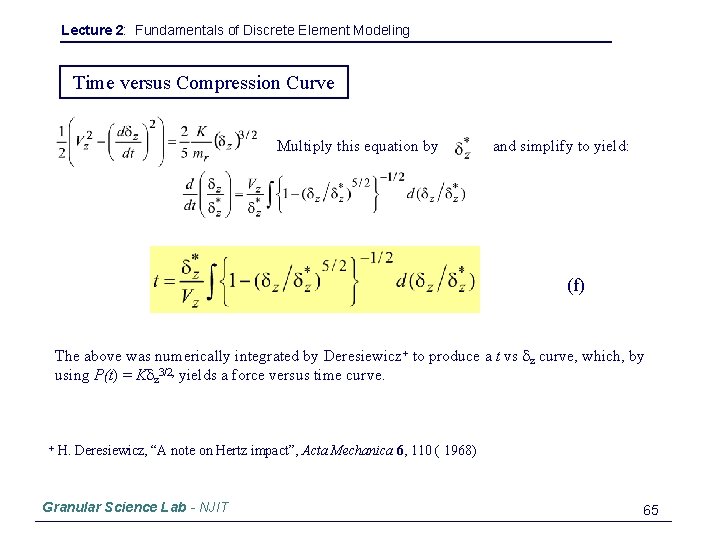

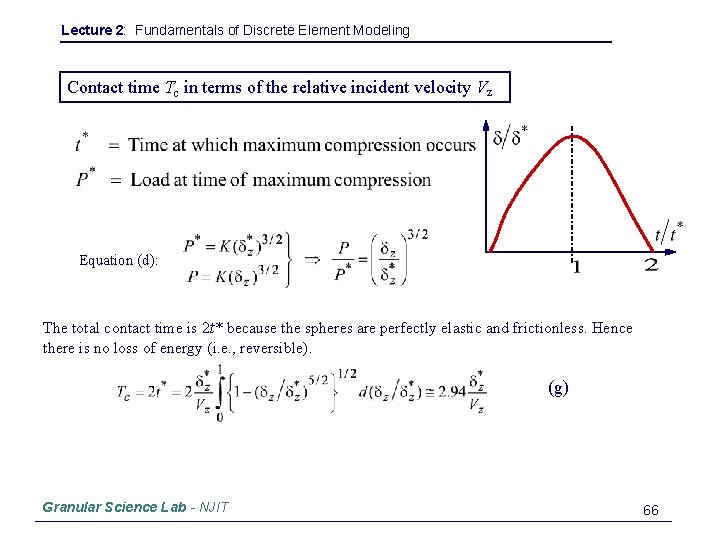

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Time versus Compression Curve Multiply this equation by and simplify to yield: (f) The above was numerically integrated by Deresiewicz+ to produce a t vs dz curve, which, by using P(t) = Kdz 3/2, yields a force versus time curve. + H. Deresiewicz, “A note on Hertz impact”, Acta Mechanica 6, 110 ( 1968) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 65

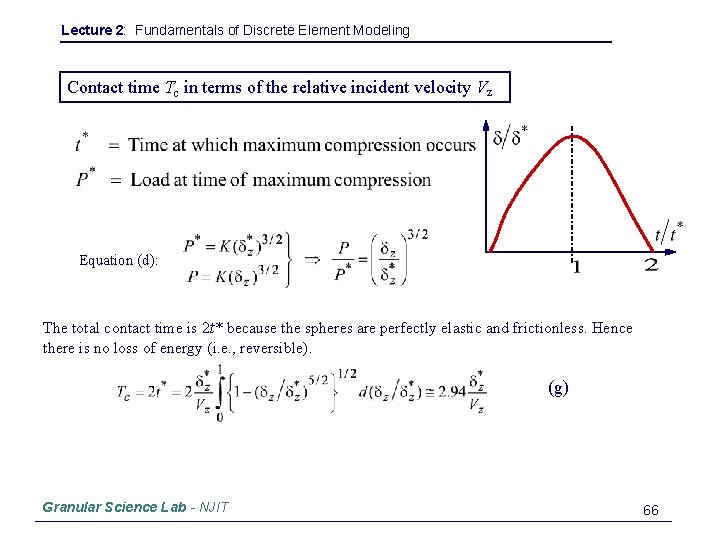

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Contact time Tc in terms of the relative incident velocity Vz Equation (d): The total contact time is 2 t* because the spheres are perfectly elastic and frictionless. Hence there is no loss of energy (i. e. , reversible). (g) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 66

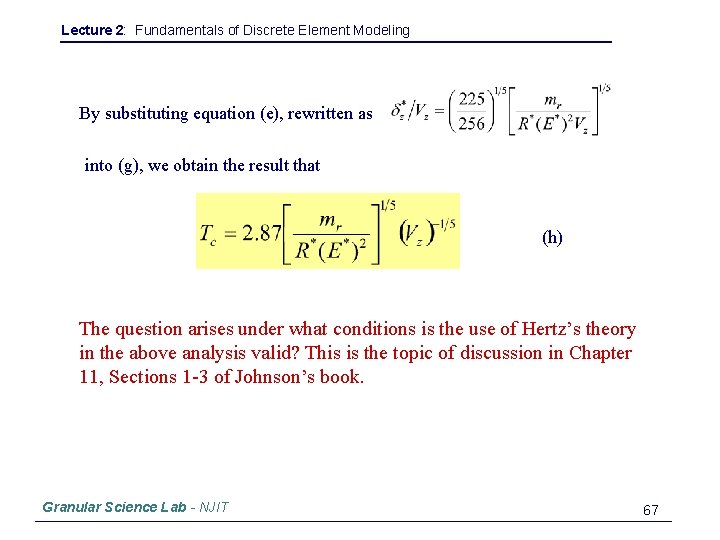

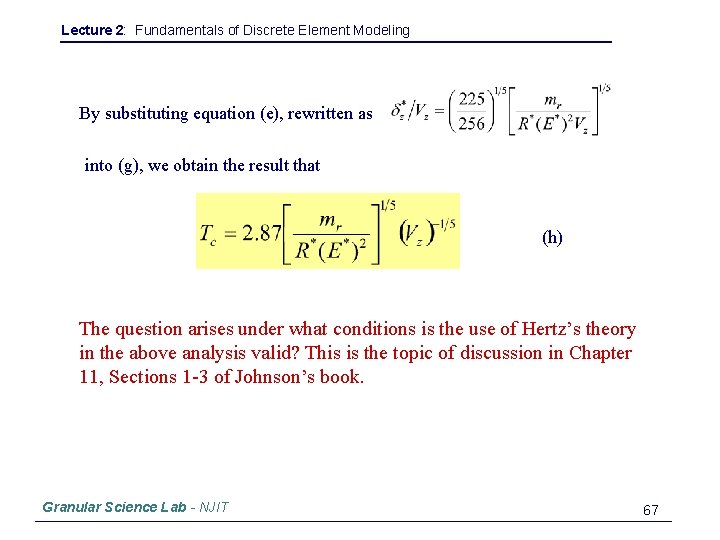

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling By substituting equation (e), rewritten as into (g), we obtain the result that (h) The question arises under what conditions is the use of Hertz’s theory in the above analysis valid? This is the topic of discussion in Chapter 11, Sections 1 -3 of Johnson’s book. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 67

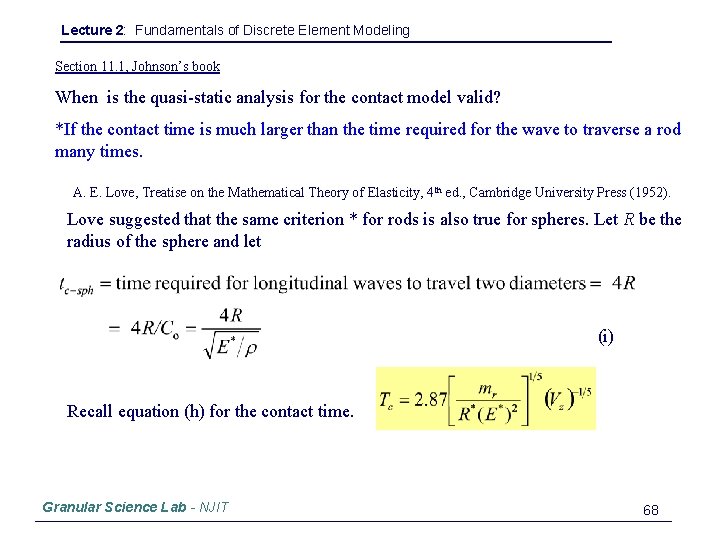

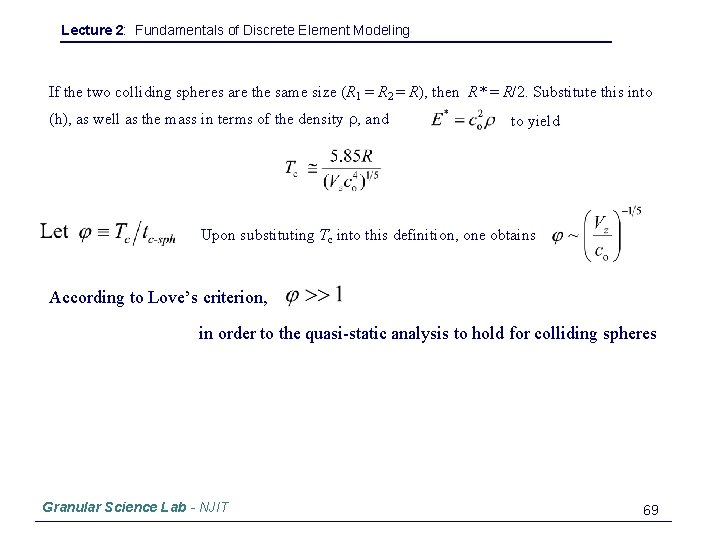

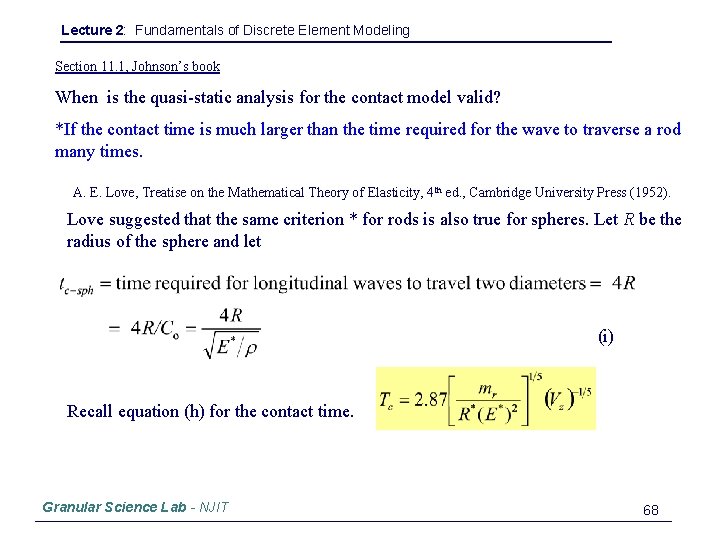

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Section 11. 1, Johnson’s book When is the quasi-static analysis for the contact model valid? *If the contact time is much larger than the time required for the wave to traverse a rod many times. A. E. Love, Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, 4 th ed. , Cambridge University Press (1952). Love suggested that the same criterion * for rods is also true for spheres. Let R be the radius of the sphere and let (i) Recall equation (h) for the contact time. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 68

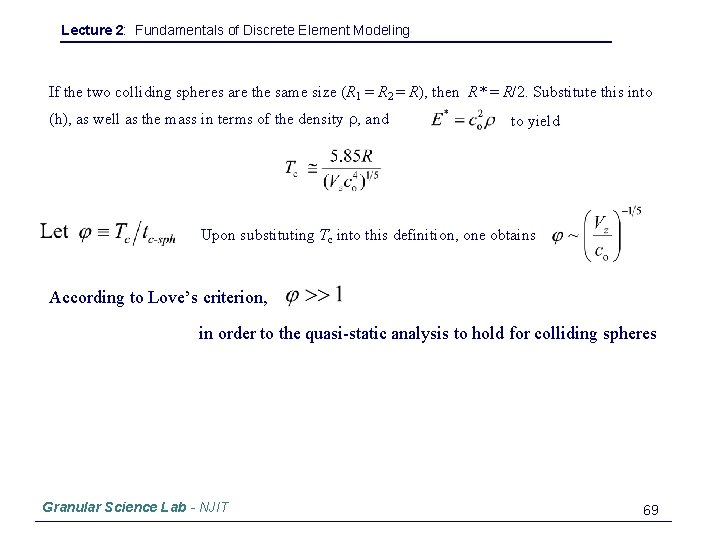

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling If the two colliding spheres are the same size (R 1 = R 2 = R), then R* = R/2. Substitute this into (h), as well as the mass in terms of the density r, and to yield Upon substituting Tc into this definition, one obtains According to Love’s criterion, in order to the quasi-static analysis to hold for colliding spheres Granular Science Lab - NJIT 69

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling End of Lecture 2 Granular Science Lab - NJIT 70

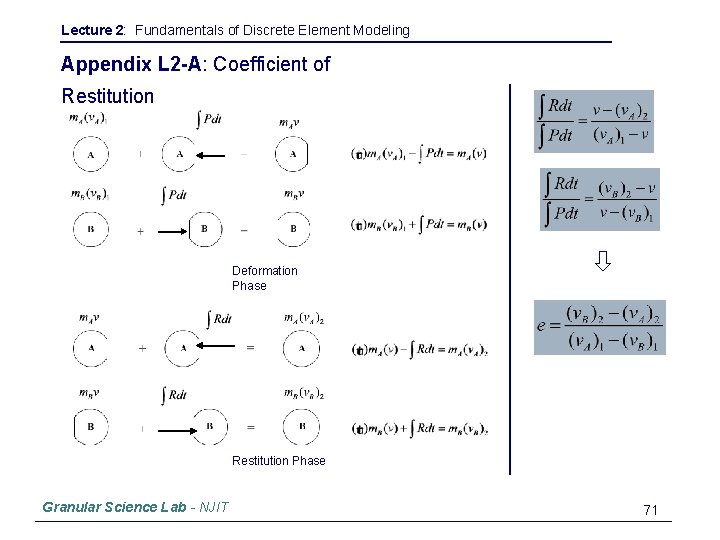

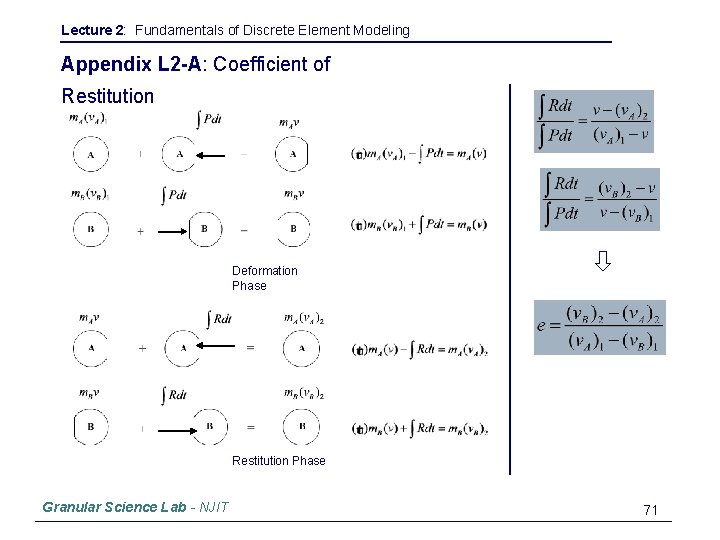

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Appendix L 2 -A: Coefficient of Restitution Deformation Phase Restitution Phase Granular Science Lab - NJIT 71

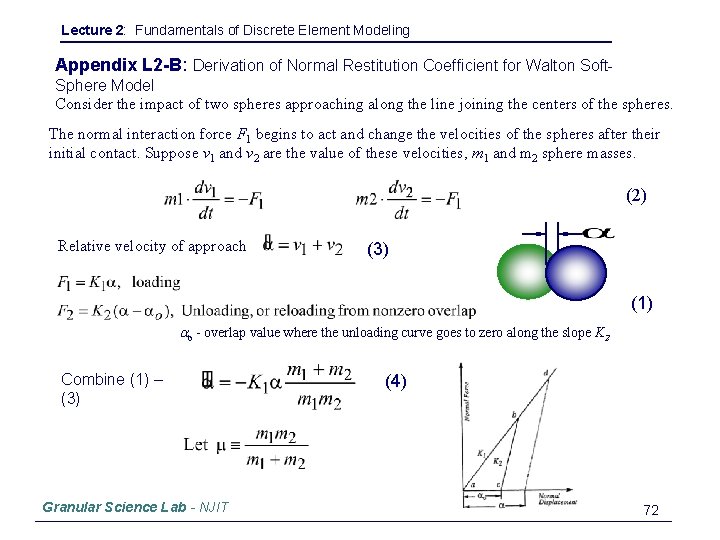

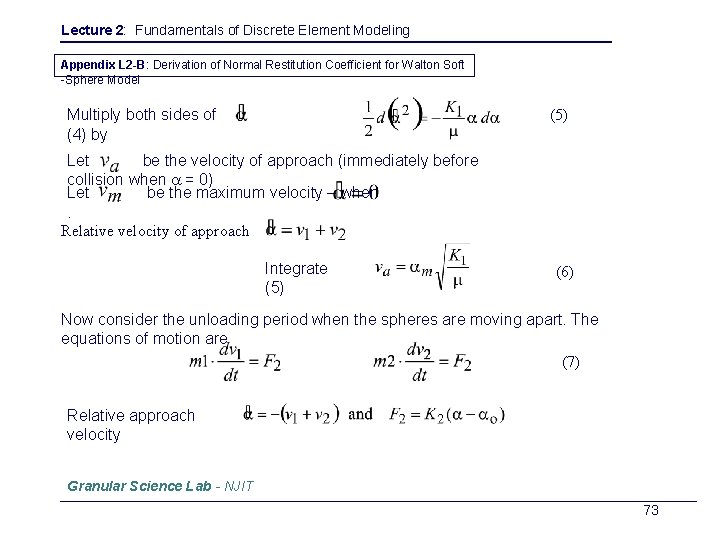

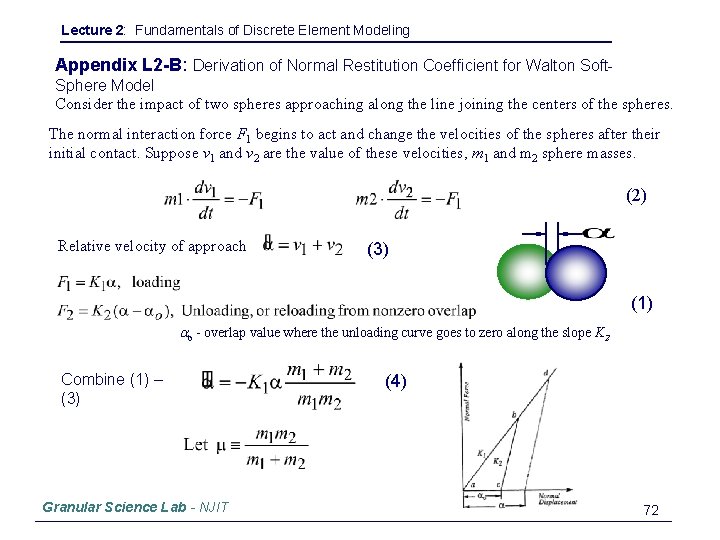

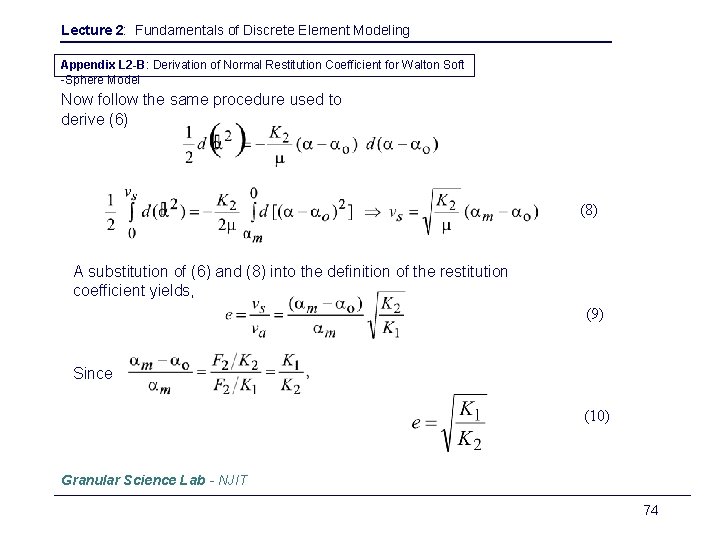

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Appendix L 2 -B: Derivation of Normal Restitution Coefficient for Walton Soft. Sphere Model Consider the impact of two spheres approaching along the line joining the centers of the spheres. The normal interaction force F 1 begins to act and change the velocities of the spheres after their initial contact. Suppose v 1 and v 2 are the value of these velocities, m 1 and m 2 sphere masses. (2) Relative velocity of approach (3) (1) ao - overlap value where the unloading curve goes to zero along the slope K 2. Combine (1) – (3) Granular Science Lab - NJIT (4) 72

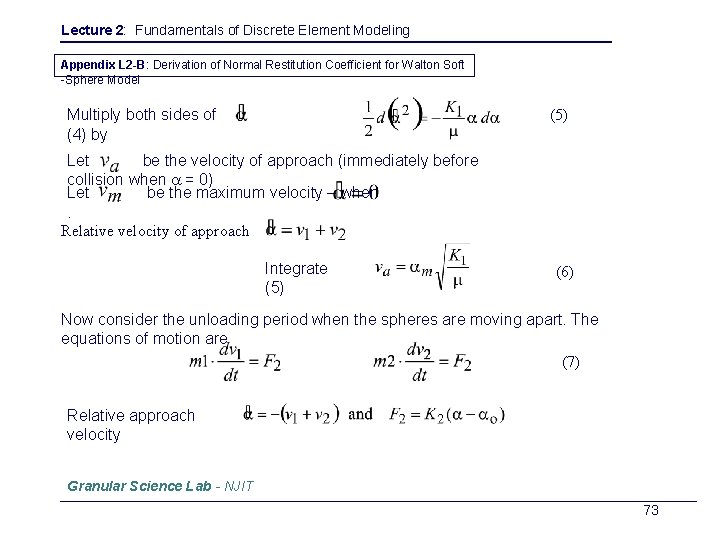

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Appendix L 2 -B: Derivation of Normal Restitution Coefficient for Walton Soft -Sphere Model Multiply both sides of (4) by (5) Let be the velocity of approach (immediately before collision when a = 0) Let be the maximum velocity – when. Relative velocity of approach Integrate (5) (6) Now consider the unloading period when the spheres are moving apart. The equations of motion are (7) Relative approach velocity Granular Science Lab - NJIT 73

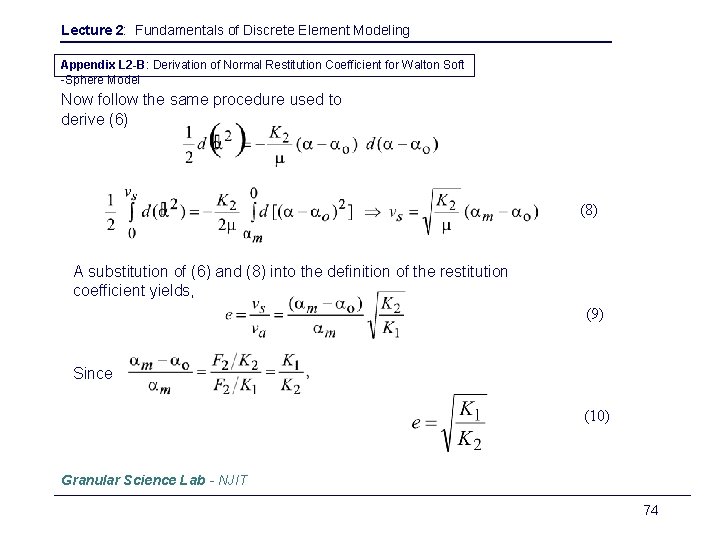

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Appendix L 2 -B: Derivation of Normal Restitution Coefficient for Walton Soft -Sphere Model Now follow the same procedure used to derive (6) (8) A substitution of (6) and (8) into the definition of the restitution coefficient yields, (9) Since (10) Granular Science Lab - NJIT 74

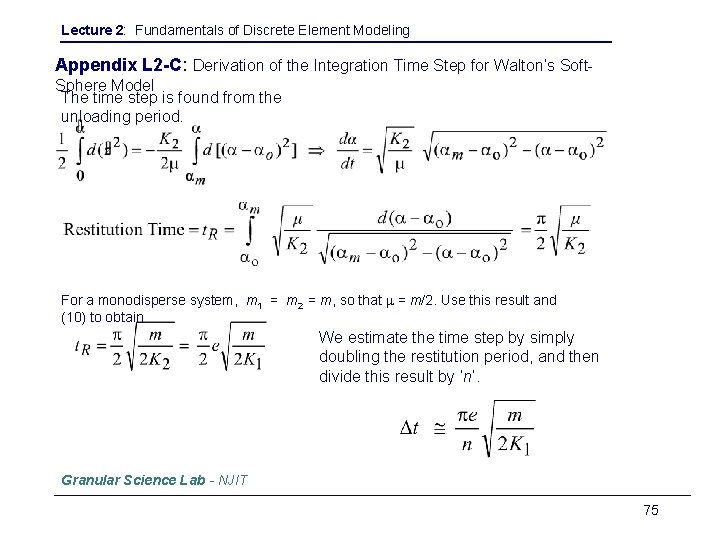

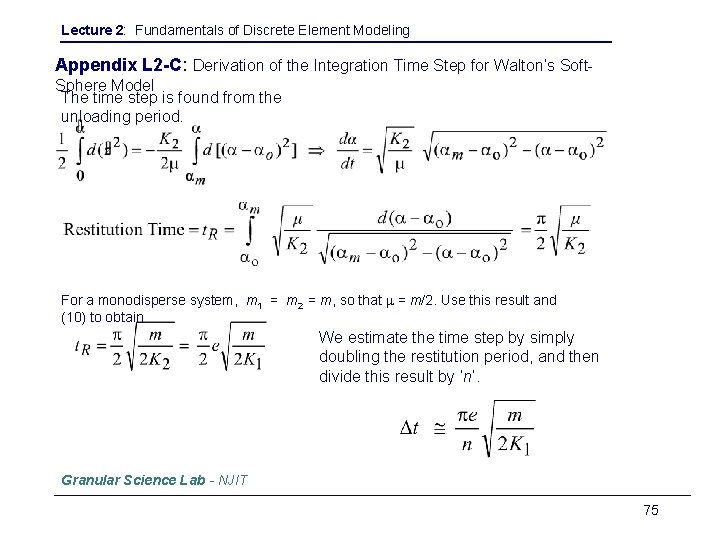

Lecture 2: Fundamentals of Discrete Element Modeling Appendix L 2 -C: Derivation of the Integration Time Step for Walton’s Soft. Sphere Model The time step is found from the unloading period. For a monodisperse system, m 1 = m 2 = m, so that m = m/2. Use this result and (10) to obtain We estimate the time step by simply doubling the restitution period, and then divide this result by ‘n’. Granular Science Lab - NJIT 75