Lecture 17 Respiration and Gas Exchange Partial Pressure

- Slides: 38

Lecture #17 Respiration and Gas Exchange

Partial Pressure • each gas in a mixture of gases exerts its own pressure = partial pressure – partial pressures denoted as “p” – applies to gases in air and gases dissolved in liquids • total pressure is sum of all partial pressures – atmospheric pressure (760 mm Hg) = p. O 2 + p. CO 2 + p. N 2 + p. H 2 O – to determine partial pressure of O 2 -- multiply 760 by % of air that is O 2 (21%) = 160 mm Hg

Respiratory Media • respiratory media – either air or water • conditions for gas exchange depend on this media – air is less dense and easier to move over respiratory surfaces – it is easy to breathe air – but humans only extract 25% of the O 2 out of the air they breathe • O 2 is plentiful in air – is always 21% of the earth’s atmosphere by volume • gas exchange from water is much more demanding – amount of O 2 dissolved in water varies with the conditions of the water • warmer and saltier – less O 2 – but it is always less than what is found in air • 40 times more O 2 in air than in water!! – water is also more dense and viscous – requires considerably more energy to move over the respiratory surface

Respiratory Surfaces • ventilation = movement of the respiratory medium over the respiratory surface • O 2 and CO 2 exchange is by diffusion and occurs across a moist surface • rate of diffusion determined by three things: – 1. surface area – 2. thickness of respiratory membrane (e. g. alveolar wall + capillary wall) – 3. diffusion coefficient – CO 2 20 X higher vs. O 2 – i. e. diffusion is faster when the area for diffusion is large and the distance is short

Respiratory Surfaces • simple animals – every cell is close enough to the external environment – gases diffuse quickly across the body surface – sponges, cnidarians and flatworms • some animals have modified their skin to act as a respiratory organ – dense network of capillaries below the surface – earthworms and some amphibians like frogs • however this is not true for larger animals – development of more complex structures like gills and lungs

• fish gas exchange – to exchange enough O 2 – fish must pass large quantities of water across the gill surface – water flows in the mouth and out the operculum (slit-like opening in the body wall) – flows over the gills – most fishes have a pumping mechanism to move water into the mouth and pharynx and out through the opercula – some elasmobranchs and open ocean bony fishes (e. g. tuna) – keep their mouth open during swimming – ram ventilation – gills are supported by gill arches – contain larger arteries and veins (branchial artery and vein) – 2 gill filaments extend from each arch and are made up of plates called lamellae – each lamella contains extensive capillary beds Gill arch Blood vessels Gill arch Water flow Operculum Gill filaments O 2 -poor blood O 2 -rich blood Lamella Water flow Blood flow

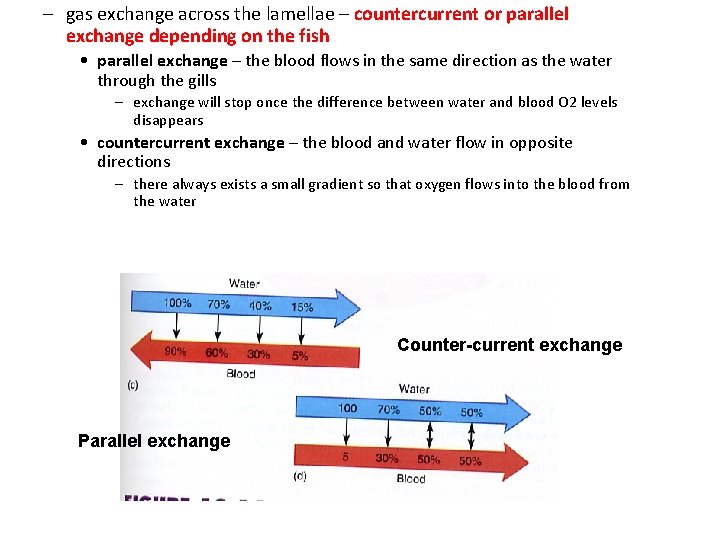

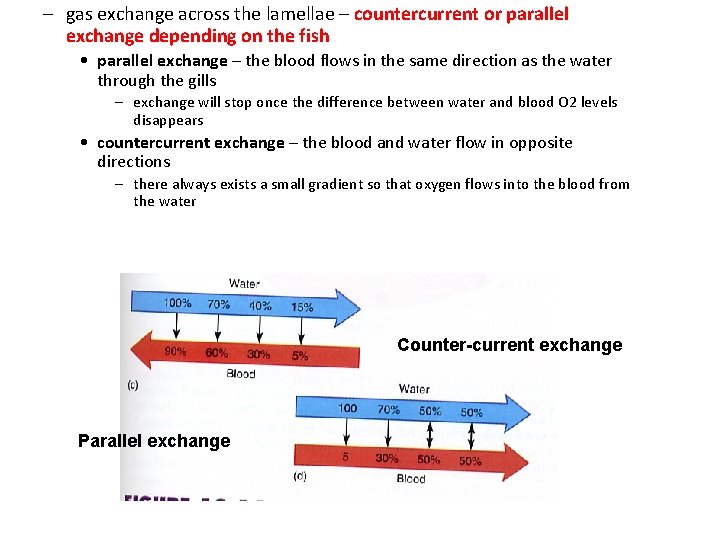

– gas exchange across the lamellae – countercurrent or parallel exchange depending on the fish • parallel exchange – the blood flows in the same direction as the water through the gills – exchange will stop once the difference between water and blood O 2 levels disappears • countercurrent exchange – the blood and water flow in opposite directions – there always exists a small gradient so that oxygen flows into the blood from the water Counter-current exchange Parallel exchange

• amphibian gas exchange: – requires a moist surface – skin can function as a respiratory organ through cutaneous respiration • the majority of its total respiration – gas exchange also occurs along the moist surfaces of the mouth and pharynx – buccopharyngeal respiration • 1 to 7% of total respiration

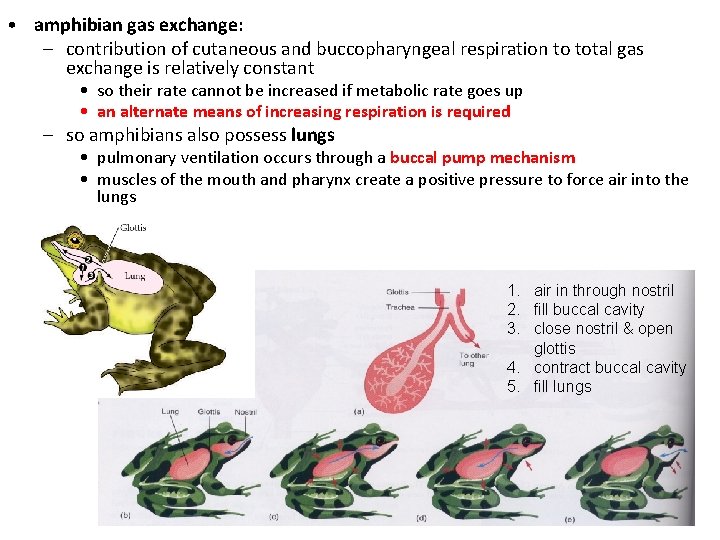

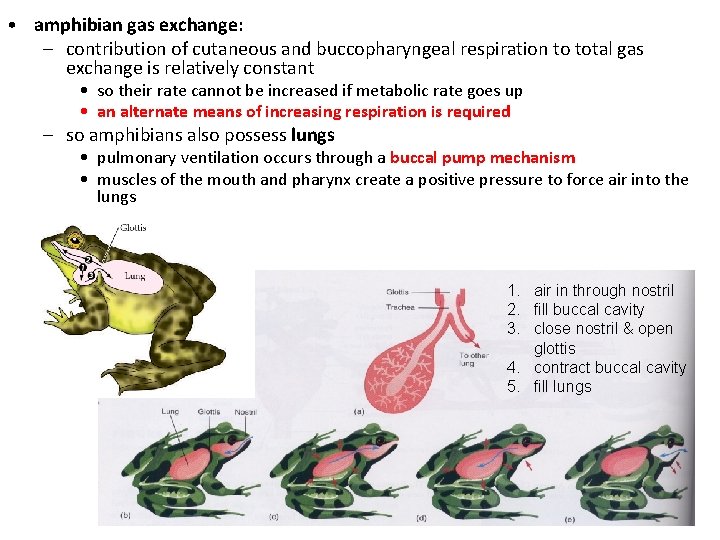

• amphibian gas exchange: – contribution of cutaneous and buccopharyngeal respiration to total gas exchange is relatively constant • so their rate cannot be increased if metabolic rate goes up • an alternate means of increasing respiration is required – so amphibians also possess lungs • pulmonary ventilation occurs through a buccal pump mechanism • muscles of the mouth and pharynx create a positive pressure to force air into the lungs 1. air in through nostril 2. fill buccal cavity 3. close nostril & open glottis 4. contract buccal cavity 5. fill lungs

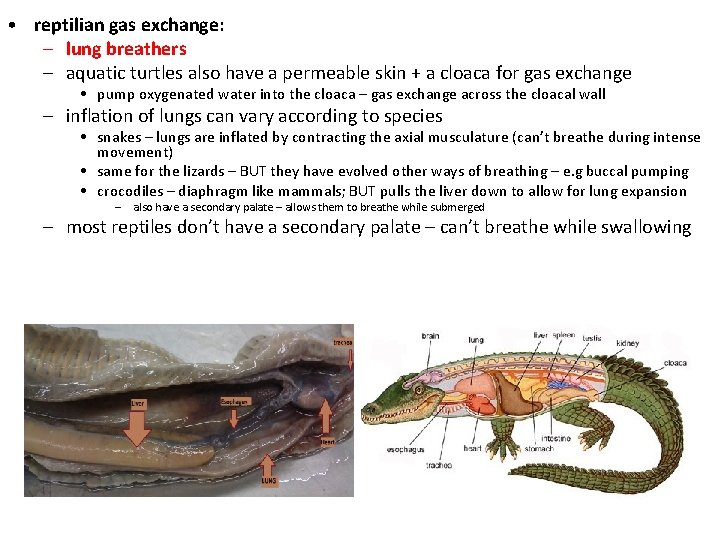

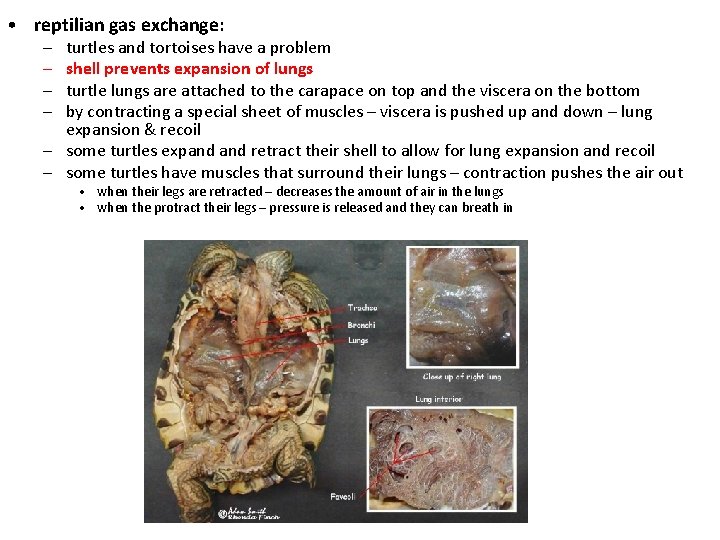

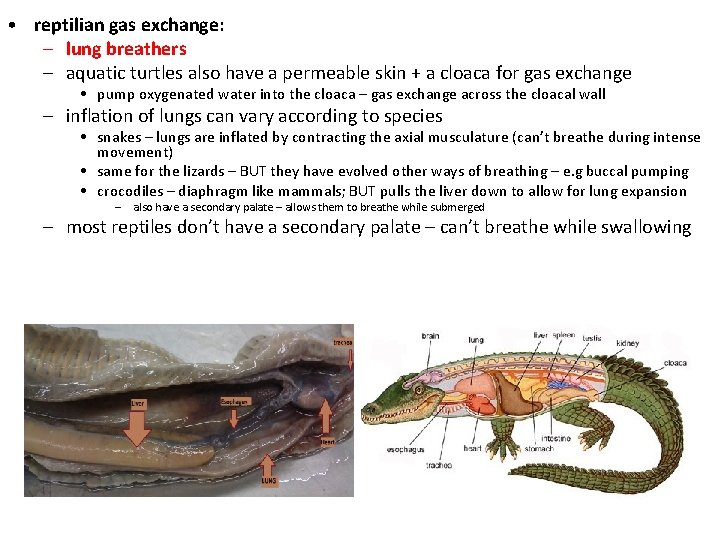

• reptilian gas exchange: – lung breathers – aquatic turtles also have a permeable skin + a cloaca for gas exchange • pump oxygenated water into the cloaca – gas exchange across the cloacal wall – inflation of lungs can vary according to species • snakes – lungs are inflated by contracting the axial musculature (can’t breathe during intense movement) • same for the lizards – BUT they have evolved other ways of breathing – e. g buccal pumping • crocodiles – diaphragm like mammals; BUT pulls the liver down to allow for lung expansion – also have a secondary palate – allows them to breathe while submerged – most reptiles don’t have a secondary palate – can’t breathe while swallowing

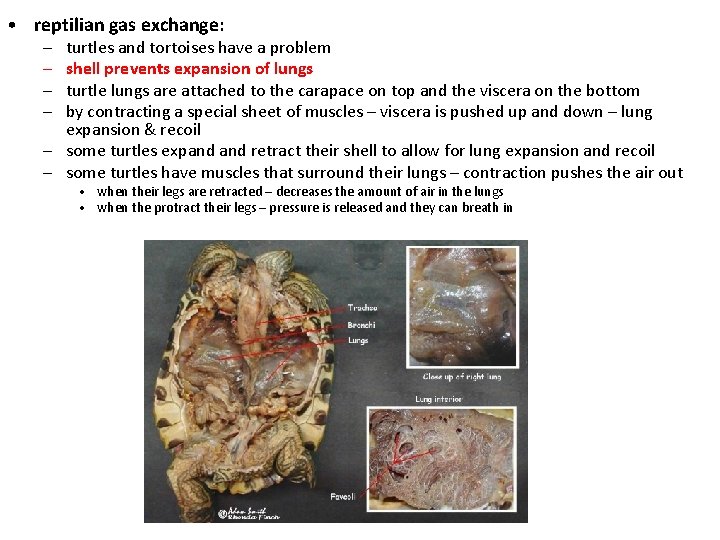

• reptilian gas exchange: – – turtles and tortoises have a problem shell prevents expansion of lungs turtle lungs are attached to the carapace on top and the viscera on the bottom by contracting a special sheet of muscles – viscera is pushed up and down – lung expansion & recoil – some turtles expand retract their shell to allow for lung expansion and recoil – some turtles have muscles that surround their lungs – contraction pushes the air out • when their legs are retracted – decreases the amount of air in the lungs • when the protract their legs – pressure is released and they can breath in

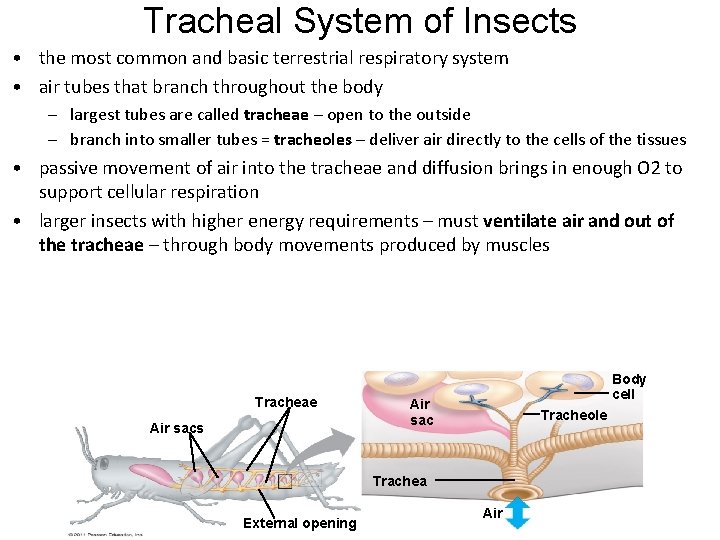

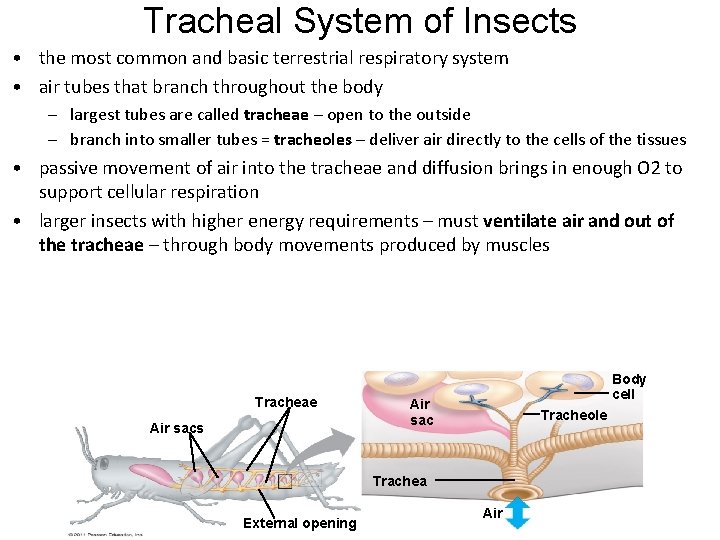

Tracheal System of Insects • the most common and basic terrestrial respiratory system • air tubes that branch throughout the body – largest tubes are called tracheae – open to the outside – branch into smaller tubes = tracheoles – deliver air directly to the cells of the tissues • passive movement of air into the tracheae and diffusion brings in enough O 2 to support cellular respiration • larger insects with higher energy requirements – must ventilate air and out of the tracheae – through body movements produced by muscles Tracheae Air sacs Body cell Air sac Tracheole Trachea External opening Air

Terrestrial Animals & the Lung • lungs are localized, regional respiratory organs • subdivided into numerous lobes, lobules and bronchopulmonary segments • these divisions are supplied by a series of branching tubes • lungs are supplied by the circulatory system – blood comes from the right side of the heart • the amphibian lung is quite small – most respiration is done by the skin • most reptiles, all birds and all mammals – respiration done lungs

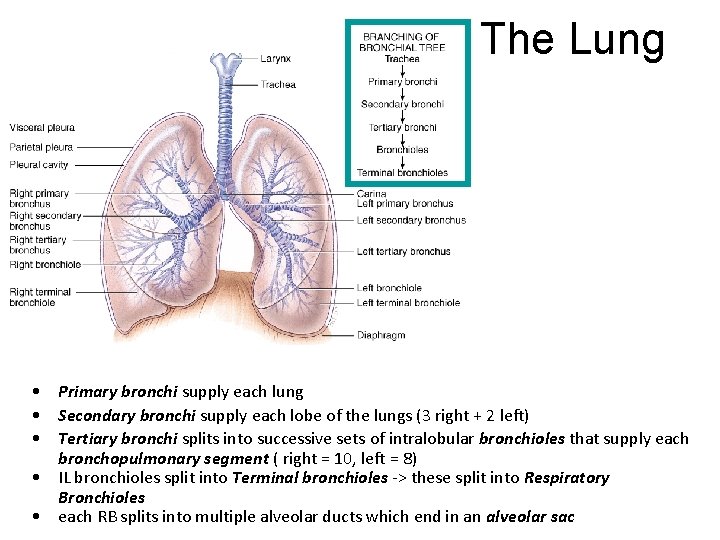

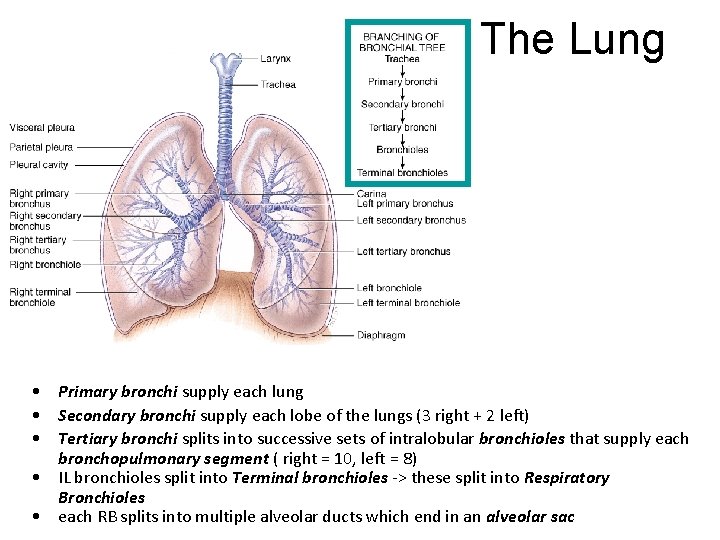

The Lung • Primary bronchi supply each lung • Secondary bronchi supply each lobe of the lungs (3 right + 2 left) • Tertiary bronchi splits into successive sets of intralobular bronchioles that supply each bronchopulmonary segment ( right = 10, left = 8) • IL bronchioles split into Terminal bronchioles -> these split into Respiratory Bronchioles • each RB splits into multiple alveolar ducts which end in an alveolar sac

The Alveolus • respiratory bronchioles branch into multiple alveolar ducts • alveolar ducts end in a grape-like cluster = alveolar sac • each grape = alveolus Branch of pulmonary vein (oxygen-rich blood) Terminal bronchiole Branch of pulmonary artery (oxygen-poor blood) Nasal cavity Pharynx Left lung Larynx (Esophagus) Alveoli 50 m Trachea Right lung Capillaries Bronchus Bronchiole Diaphragm (Heart) Dense capillary bed enveloping alveoli (SEM)

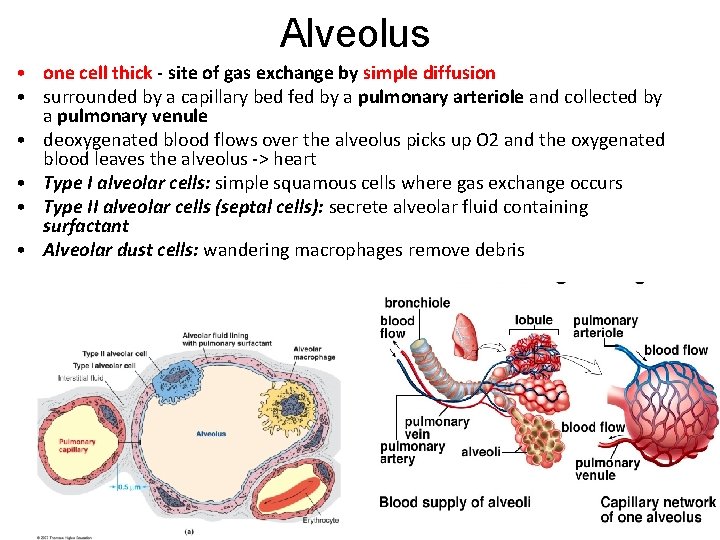

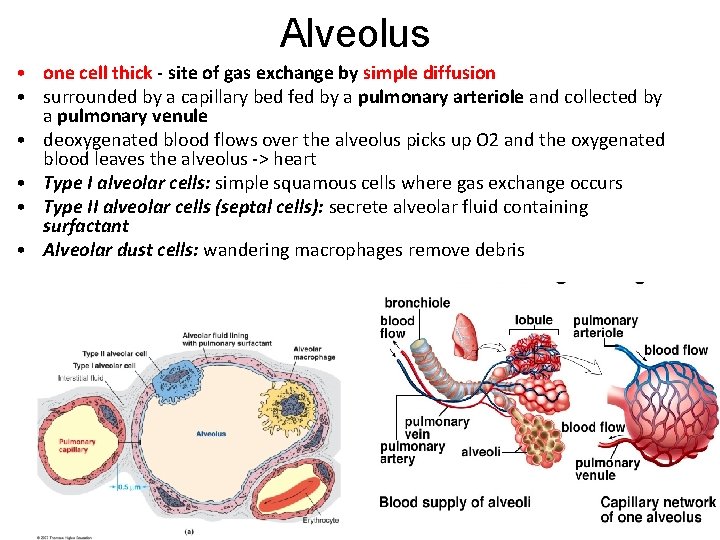

Alveolus • one cell thick - site of gas exchange by simple diffusion • surrounded by a capillary bed fed by a pulmonary arteriole and collected by a pulmonary venule • deoxygenated blood flows over the alveolus picks up O 2 and the oxygenated blood leaves the alveolus -> heart • Type I alveolar cells: simple squamous cells where gas exchange occurs • Type II alveolar cells (septal cells): secrete alveolar fluid containing surfactant • Alveolar dust cells: wandering macrophages remove debris

Ventilation & Breathing • ventilation = movement of the respiratory medium over the respiratory surface • amphibians – use positive pressure breathing – inflate their lungs by forcing air into them – floor of the mouth lowers and air is drawn in through the nostrils – close the nostrils and mouth – floor of the mouth rises – increase in pressure forces air down the trachea • mammals – use negative pressure breathing – change the volume of the lungs to either increase or decrease air pressure within it – moves the air in and out • birds – unique mechanism involving negative pressure breathing

• respiratory system is designed to be efficient and to provide the flight muscles with enough oxygen • external nares located in the bill – draws air in – eventually enters into the bronchii • bronchi connect to air sacs that occupy much of the body & to the lungs • lung does not contain alveoli – but contains parabronchii – tiny channels for gas exchange • inspiration and expiration results from increasing and decreasing the volume of the thorax and from the expansion and compression of the air sacs • bird actually uses two rounds of inhalation/exhalation to move a volume of air through its respiratory system Birds Anterior air sacs Posterior air sacs Lungs Airflow Air tubes (parabronchi) in lung 1 mm Posterior air sacs 2 Lungs 3 Anterior air sacs 4 1 1 First inhalation 3 Second inhalation 2 First exhalation 4 Second exhalation

• 1 st inhalation – air moves into the posterior/abdominal air sacs • 1 st exhalation – posterior air sac contracts – forces air into the lungs for additional gas exchange • 2 nd inhalation – air passes from the lungs into the anterior air sacs; new air moves into the posterior air sacs • 2 nd exhalation – anterior air sacs contract and air moves out of body; posterior air sacs contract and a new volume of air moves in to lung • due to this arrangement – birds have a near continuous movement of O 2 rich air over the respiratory surfaces of the lungs Birds Anterior air sacs Posterior air sacs Lungs Airflow Air tubes (parabronchi) in lung 1 mm Posterior air sacs 2 Lungs 3 Anterior air sacs 4 1 1 First inhalation 3 Second inhalation 2 First exhalation 4 Second exhalation

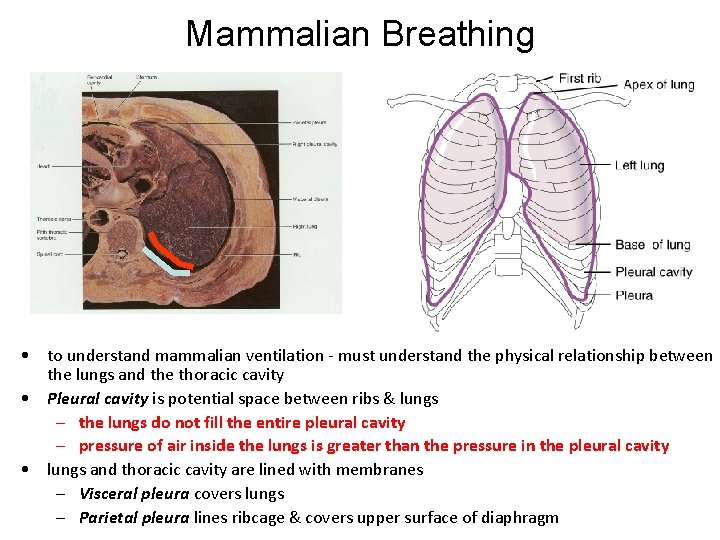

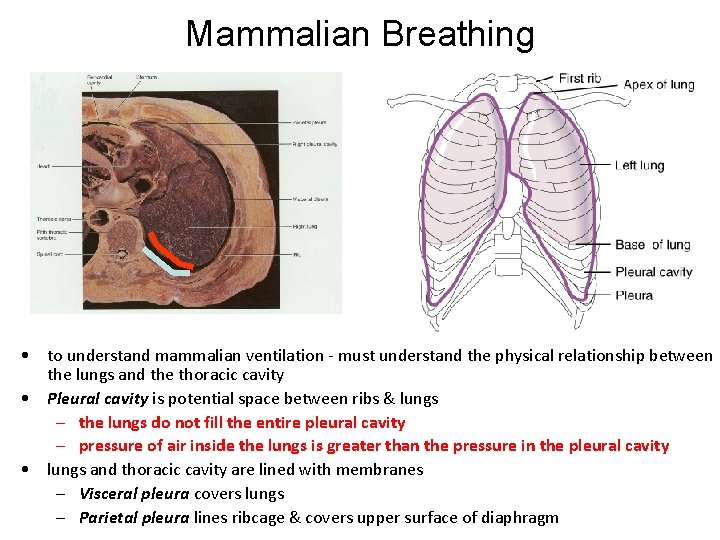

Mammalian Breathing • to understand mammalian ventilation - must understand the physical relationship between the lungs and the thoracic cavity • Pleural cavity is potential space between ribs & lungs – the lungs do not fill the entire pleural cavity – pressure of air inside the lungs is greater than the pressure in the pleural cavity • lungs and thoracic cavity are lined with membranes – Visceral pleura covers lungs – Parietal pleura lines ribcage & covers upper surface of diaphragm

Respiratory pressures • two different pressures need to be considered – 1. atmospheric (barometric) pressure • caused by the weight of air on objects on the Earth’s surface • sea level = 760 mm Hg – 2. intrapulmonary (intra-alveolar) pressure • pressure within the lungs (within each alveolus) • when not ventilating – pressure of air inside the lungs = pressure of air outside the body • ventilation happens because of a pressure gradient between AP and IP

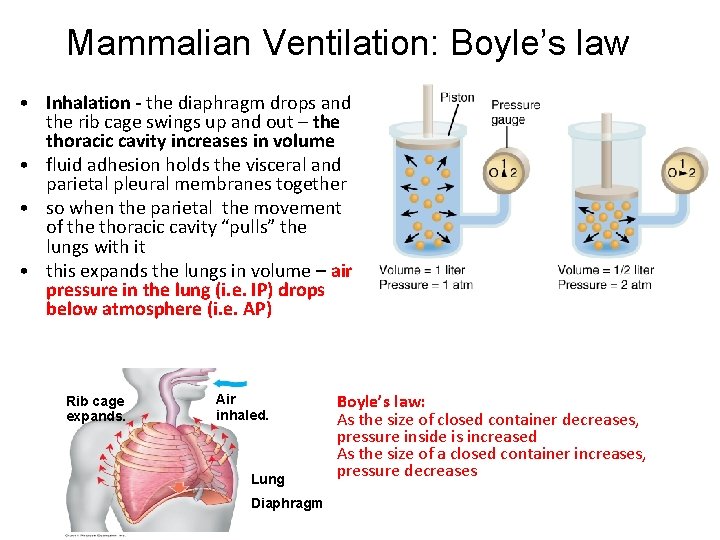

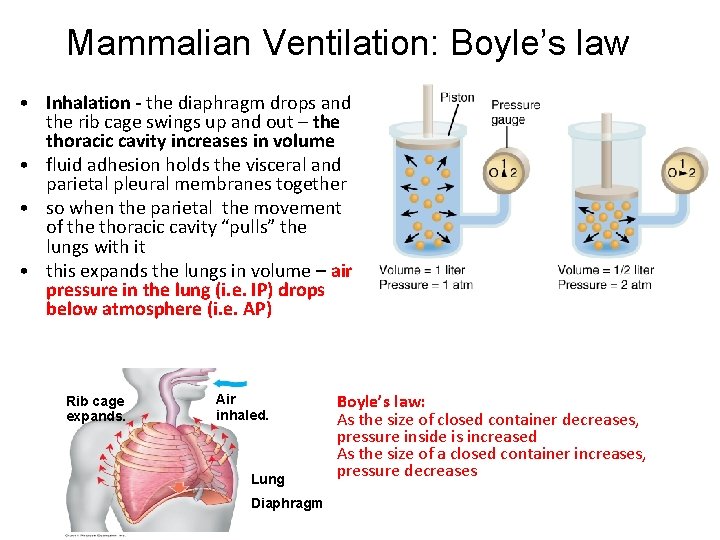

Mammalian Ventilation: Boyle’s law • Inhalation - the diaphragm drops and the rib cage swings up and out – the thoracic cavity increases in volume • fluid adhesion holds the visceral and parietal pleural membranes together • so when the parietal the movement of the thoracic cavity “pulls” the lungs with it • this expands the lungs in volume – air pressure in the lung (i. e. IP) drops below atmosphere (i. e. AP) Rib cage expands. Air inhaled. Lung Diaphragm Boyle’s law: As the size of closed container decreases, pressure inside is increased As the size of a closed container increases, pressure decreases

Mammalian Ventilation: Boyle’s law • Exhalation – the diaphragm comes back up and the rib cage swings back down – the thoracic cavity decreases in volume • PLUS – elastic recoil of the lung tissue decreases volume • lung volume decreases and the air pressure within the lungs increases vs. atmospheric • air moves out to equilibrate Rib cage gets smaller. Air exhaled.

Mammalian Ventilation: Boyle’s law • additional muscles can be used to increase and decrease the volume of the thoracic cavity more than normal – e. g. neck muscles, internal intercostals, abdominals • other animals use the rhythmic movement of organs in their abdomen to increase breathing volumes – e. g. kangaroo Rib cage gets smaller. Air exhaled.

Respiratory Volumes and Capacities • inspiratory capacity (IC) = max. amnt of air taken in after a normal exhalation, 3500 ml • vital capacity = max. amnt of air capable of inhaling, IRV + TV + ERV = 4600 ml • total lung capacity = VC + RV = 6000 ml • (TV) = amnt of air that enters or exits the lungs 500 ml per inhalation • inspiratory reserve volume (IRV) = IC - TV, 3000 ml • expiratory reserve volume (ERV) = amnt of air forcefully exhaled, 1100 ml • residual volume (RV) = amnt of air left in lungs after forced expiration = 1200 ml • functional residual capacity = ERV + RV, 2300 ml

Control of Breathing • controlled by three clusters of neurons that make up the Respiratory Center • 1. medullary rhythmicity area – in the medulla oblongata – controls the rate and depth of breathing • 2. pneumotaxic area – in the pons – inhibits the MRA to shorten the breath • 3. apneustic area – in the pons – works with the MRA to prolong the breath • detects changes in the p. H of the CSF surrounding the brain

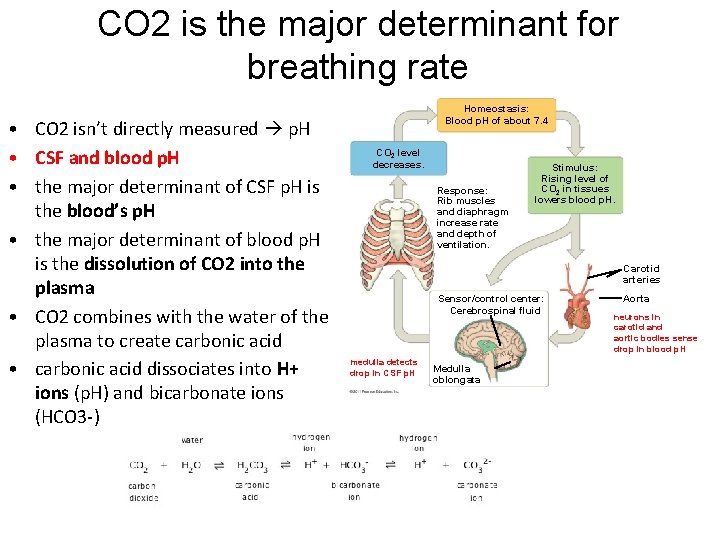

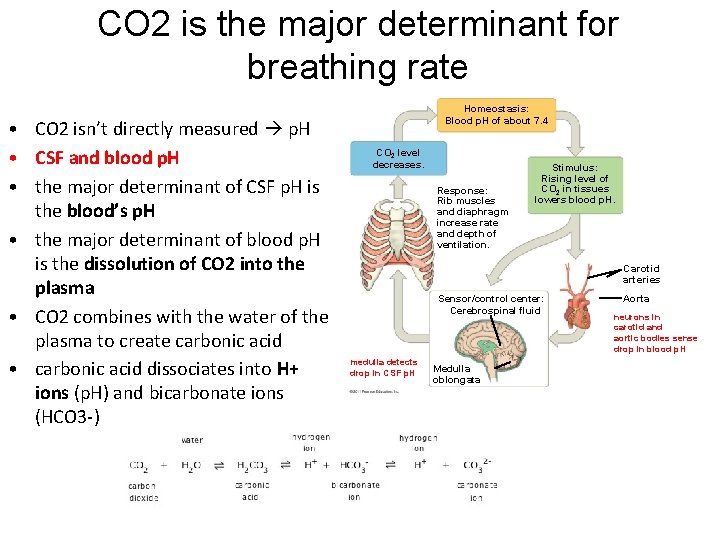

CO 2 is the major determinant for breathing rate • CO 2 isn’t directly measured p. H • CSF and blood p. H • the major determinant of CSF p. H is the blood’s p. H • the major determinant of blood p. H is the dissolution of CO 2 into the plasma • CO 2 combines with the water of the plasma to create carbonic acid • carbonic acid dissociates into H+ ions (p. H) and bicarbonate ions (HCO 3 -) Homeostasis: Blood p. H of about 7. 4 CO 2 level decreases. Response: Rib muscles and diaphragm increase rate and depth of ventilation. Stimulus: Rising level of CO 2 in tissues lowers blood p. H. Carotid arteries Sensor/control center: Cerebrospinal fluid medulla detects drop in CSF p. H Medulla oblongata Aorta neurons in carotid and aortic bodies sense drop in blood p. H

Respiratory pigments • CO 2 dissolves in the water of the plasma • but O 2 dissolves poorly in plasma – – reduces the amount of O 2 that the blood can carry for intense exercise – human needs 2 L of O 2 per minute!! normally only 4. 5 m. L of O 2 can dissolve into a liter of plasma human heart would need to pump 555 L of blood per minute for this exercise level • so there is the need for a respiratory pigment to bind oxygen • hemocyanin – respiratory pigment of molluscs, arthopods, annelids – has copper as it’s oxygen binding element • hemoglobin used by most other animals – uses iron to bind oxygen – acts as an oxygen sponge – allows for the transport of significant amounts of O 2 in the blood

Hemoglobin • • comprised of 4 proteins called globin each globin has a heme group each heme group has an iron-containing pigment at its core each iron atom binds one O 2 molecule – as one heme binds one O 2 – the other three increase their affinity for their O 2 “partners” – as one heme releases its O 2 – the other three lose their affinity for their O 2 • so each Hb can carry four O 2 molecules

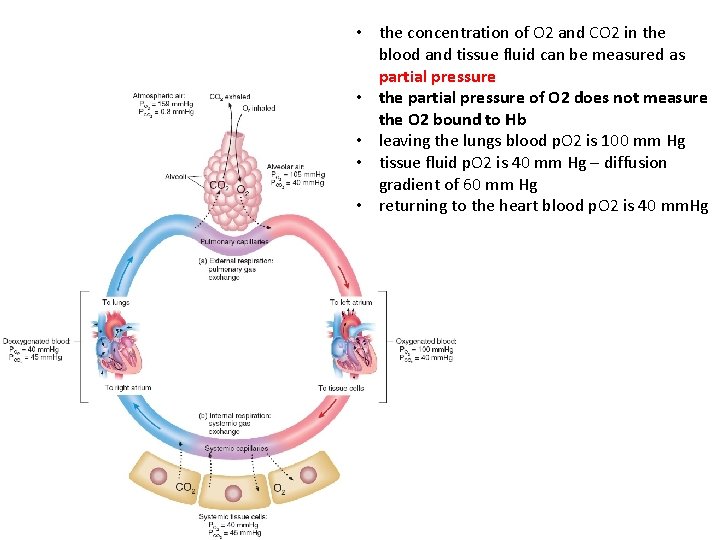

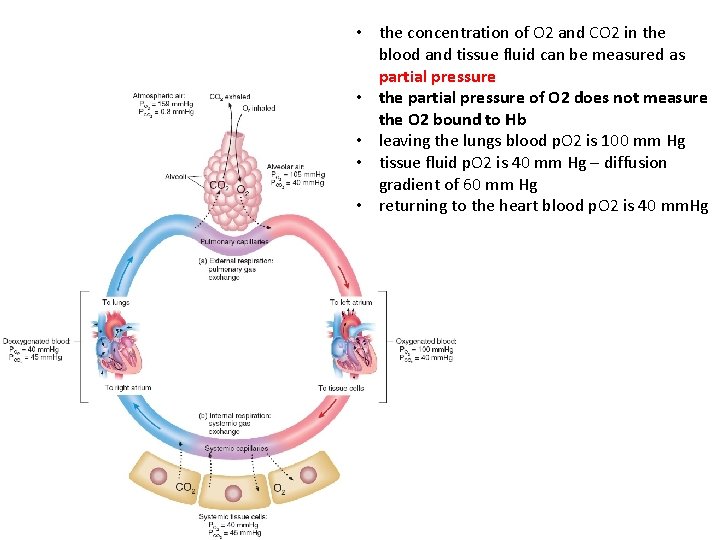

• the concentration of O 2 and CO 2 in the blood and tissue fluid can be measured as partial pressure • the partial pressure of O 2 does not measure the O 2 bound to Hb • leaving the lungs blood p. O 2 is 100 mm Hg • tissue fluid p. O 2 is 40 mm Hg – diffusion gradient of 60 mm Hg • returning to the heart blood p. O 2 is 40 mm. Hg

O 2 saturation of hemoglobin (%) Hemoglobin & O 2 100 O 2 unloaded to tissues at rest 80 O 2 unloaded to tissues during exercise 60 40 20 0 0 20 Tissues during exercise 40 60 Tissues at rest PO 2(mm Hg) 80 100 Lungs (a) PO 2 and hemoglobin dissociation at p. H 7. 4 • y axis = oxygen saturation of Hb (%) • x axis = partial pressure of O 2 of the blood in tissues and lungs • the distinct shape of this curve means that even when p. O 2 is low – O 2 saturation is adequate • e. g. at a p. O 2 of 100 mm. Hg – Hb is 98% saturated • at a p. O 2 of 80 mm. Hg – Hb is 96% saturated • at a p. O 2 of 40 mm. Hg – Hb is still 70% saturated

Hemoglobin & O 2 • O 2 saturation of Hb can be affected by physical factors in the blood • temperature – shifts left when temps decrease; shifts right when temp increases • acidity – shifts left when p. H increases; shifts right when p. H decreases (acidity increases) • p. CO 2 – shifts left when p. CO 2 decreases; shifts right when p. CO 2 increases Bohr shift: O 2 saturation is inversely related to p. H and p. CO 2

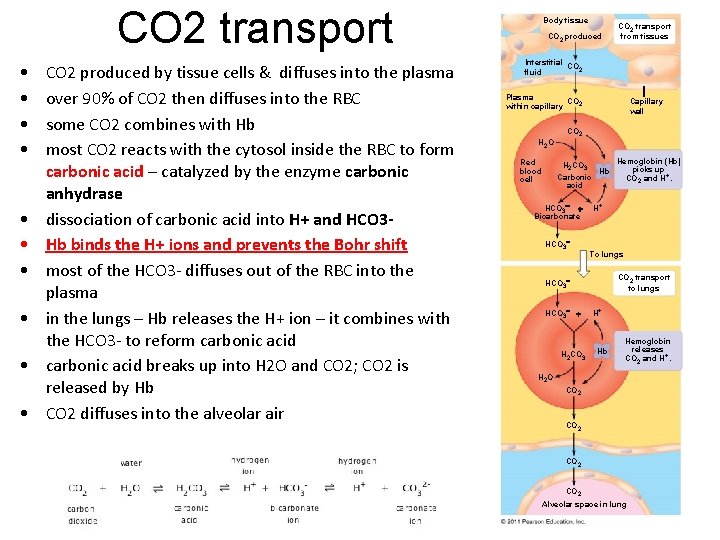

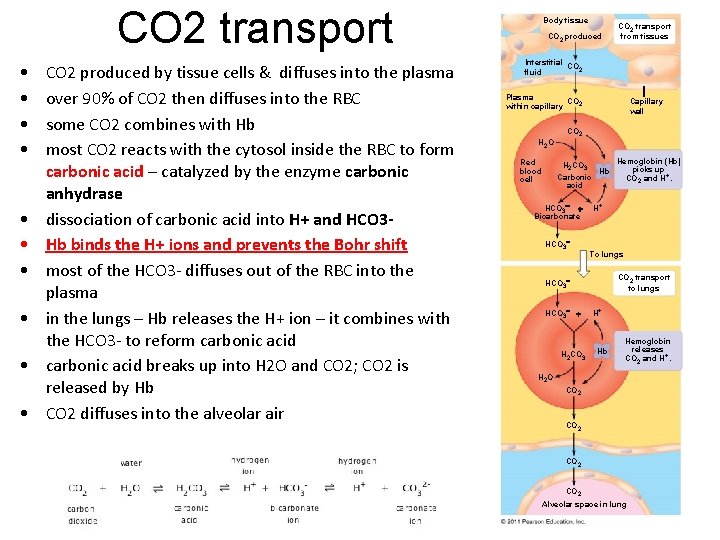

CO 2 transport • • • CO 2 produced by tissue cells & diffuses into the plasma over 90% of CO 2 then diffuses into the RBC some CO 2 combines with Hb most CO 2 reacts with the cytosol inside the RBC to form carbonic acid – catalyzed by the enzyme carbonic anhydrase dissociation of carbonic acid into H+ and HCO 3 Hb binds the H+ ions and prevents the Bohr shift most of the HCO 3 - diffuses out of the RBC into the plasma in the lungs – Hb releases the H+ ion – it combines with the HCO 3 - to reform carbonic acid breaks up into H 2 O and CO 2; CO 2 is released by Hb CO 2 diffuses into the alveolar air Body tissue CO 2 produced CO 2 transport from tissues Interstitial CO 2 fluid Plasma CO 2 within capillary Capillary wall CO 2 H 2 O Red blood cell H 2 CO 3 Hb Carbonic acid HCO 3 Bicarbonate HCO 3 H+ To lungs CO 2 transport to lungs HCO 3 H 2 CO 3 Hemoglobin (Hb) picks up CO 2 and H+. H+ Hb Hemoglobin releases CO 2 and H+. H 2 O CO 2 Alveolar space in lung

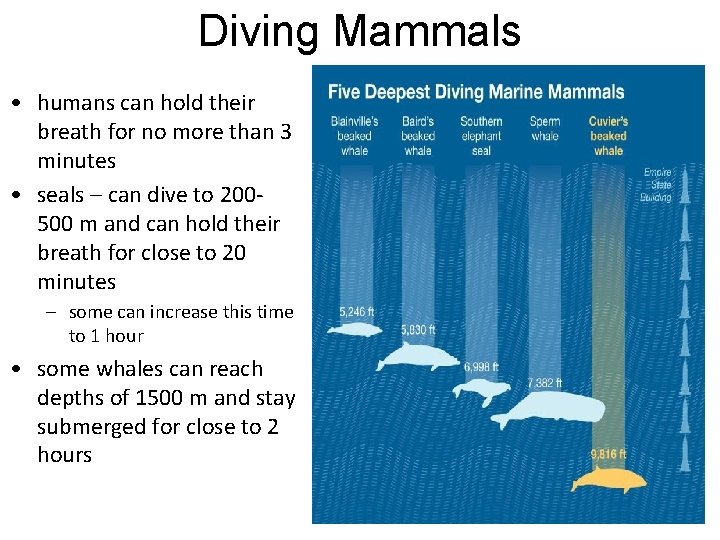

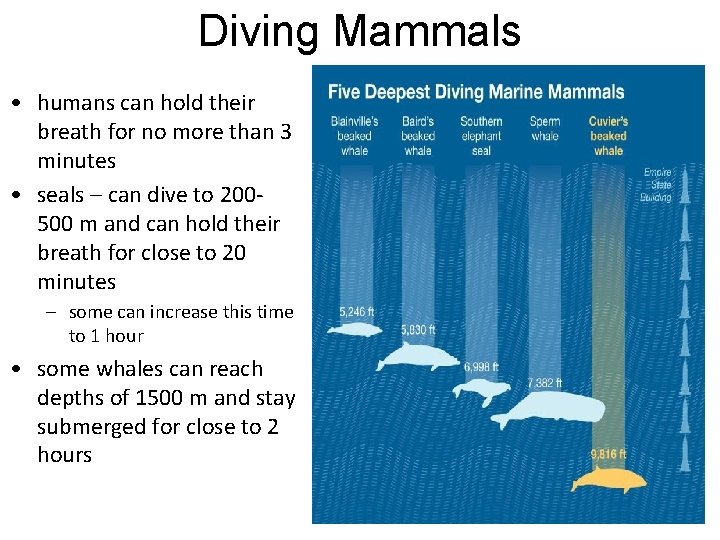

Diving Mammals • humans can hold their breath for no more than 3 minutes • seals – can dive to 200500 m and can hold their breath for close to 20 minutes – some can increase this time to 1 hour • some whales can reach depths of 1500 m and stay submerged for close to 2 hours

Diving Mammals: Respiratory Challenges • Water pressure increases at 1 atmosphere (atm) for each 10 m of water depth • Increasing water pressure on the outside of an animal will squeeze any air-filled spaces inside the animal • Absorption of gases from highly pressurized air poses serious problems. • The increasing hydrostatic pressure on the animal’s respiratory system can create decompression sickness if the animal returns to the surface of the water too quickly. – Sonar sounds and commercial fishing as possible sources that force animals to ascend to the water surface too quickly

Diving Mammals • adaptations: – 1. ability to store large amounts of O 2 in their muscle mass • high concentration of myoglobin in their muscles – 2. physical adaptations to decrease hydrostatic pressure • torpedo shape decreases hydrostatic pressure – 3. adaptations to conserve O 2 • torpedo shape - takes little effort to swim • their buoyancy allows them to change depths easily – 4. regulatory mechanisms re-routes blood to the brain, spinal cord, eyes, adrenal glands • shut off in other areas during a dive – e. g. digestive • known as the “dive response”

Diving Mammals • Circulatory adaptations: • 1. large amounts of positively-charged myoglobin in muscles – Myoglobin has a higher affinity for O 2 vs. hemoglobin • 2. organs other than the muscles can store oxygen • 3. large overall blood volumes (2 X as much blood per muscle mass vs. terrestrial animals) – More hemoglobin • 4. heart rate dramatically slows when diving • 5. peripheral blood vessels are constricted

Diving Mammals • Respiratory adaptations: • 1. lung volume is lower in diving mammals • 2. whale lungs have more rigid cartilaginous support and elasticity.