Lecture 15 Crosssectional studies and ecologic studies Jeffrey

- Slides: 32

Lecture 15: Cross-sectional studies and ecologic studies Jeffrey E. Korte, Ph. D BMTRY 747: Foundations of Epidemiology II Department of Public Health Sciences Medical University of South Carolina Spring 2015

Cross-sectional studies • Also known as prevalence studies • Exposure status and disease status are determined at a single timepoint (or over a short period of time) • Prevalence rates can be compared among those with and without the exposure, or for varying levels of exposure • Always good for public health planning; can also be good for understanding disease etiology • Often cross-sectional analyses are published based on the baseline visit for a cohort study

Cross-sectional studies: understanding disease etiology • Terrific study design for understanding exposures that are immutable (or are relatively invariant over the long term): – Genetically determined factors • Blood type, genetic polymorphisms, sex, hair color, tanning ability – Ethnicity – Birth order – Education • This is because the problem of temporal ambiguity (cause versus effect) is potentially obviated

Cross-sectional studies: understanding disease etiology • Reasonable study design for understanding any exposure in relation to diseases with: – Slow onset – Long duration – Low likelihood of seeking medical care – e. g. arthritis, bronchitis, mental disorders • This is because these diseases are difficult to study using other study designs

Cross-sectional studies: understanding disease etiology • If disease has a slow onset: – Cohort study is impractical • Difficult to define disease incidence • Need long follow-up, probably large sample size – Case-control study may be impractical (if it is difficult to define or identify cases) • Disease of long duration: – Makes sense for a cross-sectional study: prevalence will be higher than for a disease of short duration

Cross-sectional studies: understanding disease etiology • If medical care is not sought at outset: – Case-control study is impractical, or at least difficult to interpret (case group would be mostly people with advanced disease)

Cross-sectional studies: advantages • Relatively quick • Relatively inexpensive • Cross-sectional study can be clearly representative of a specific population – Population random sample – Sample of people seeking medical care

Cross-sectional studies: limitations • Difficult to separate cause and effect – “Exposure” and “disease” are measured at the same time (may be impossible to determine which came first) – Example 1: people in low social classes have higher prevalence rates of: • many mental illnesses • chronic bronchitis • other factors making job retention less likely

Cross-sectional studies: limitations • Difficult to separate cause and effect – Example 2: rates of chronic bronchitis are higher in low-pollution areas (people moved away from high-pollution areas) • Conclusion: current exposure level may not be related to (or, may be inversely related to) the exposure level experienced when disease began

Cross-sectional studies: limitations • Prevalent cases are over-represented by cases of long duration – People who recover or die quickly are less likely to be designated as diseased in a cross-sectional study – Relationship between exposure and disease may differ between short-duration and long-duration cases • Characteristics of cases (exposure or disease) may differ: vulnerability, cofactors, alternative etiologic pathways, disease subtypes, etc. – Less problematic if disease is normally of long duration

Cross-sectional studies: limitations • If disease may have remissions: – Cases in remission may be (incorrectly) classified as being disease-free – e. g. cancer, viral infections • If disease may be treated: – Cases being successfully treated may be (incorrectly) classified as being disease-free – e. g. hypertension, hypercholesterolemia

Cross-sectional studies: choice of study population • May be selected based on: – Exposure status (e. g. age range, unusual ethnicity, unusual occupation) – Geographic area (e. g. neighborhood, proximity to point source of exposure, etc. ) • Sampling procedures have major impact on study efficiency (depending on question)

Cross-sectional studies: measurement of exposure • Similar to cohort and case-control studies – Questionnaires, records, lab tests, physical measurements, special procedures • Important to determine when exposure occurred, and how long exposure persisted – Limitations of self-report (memory lapse, bias)

Cross-sectional studies: measurement of disease • Similar to cohort and case-control studies • Questionnaire: symptomatology – e. g. evidence of chronic respiratory disease • Physical examination: signs – e. g. evidence of arthritis in joints • Special procedures – e. g. tests of respiratory function for chronic respiratory disease; X-rays for arthritis

Cross-sectional studies: measurement of disease • Time of disease onset should be determined – First symptoms and/or diagnosis • Disease may be detected during the study • Onset may be gradual • For diseases with periods of remission: – Ask about past symptoms and/or diagnosis • Diagnostic criteria must be established in advance, applied in a standard way – If standard criteria are used, surveys from different areas can be compared

Cross-sectional studies: analysis: basic measures • Prevalences: compare exposure groups – “prevalence rate” (redundant jargon) – prevalence ratio – prevalence rate difference • Prevalence odds – Odds ratio (odds of having disease, not developing disease)

Cross-sectional studies: analysis: controlling for confounding • Matching (control during design phase): not usually done – General population samples: information on matching factors is not usually available before study is initiated

Cross-sectional studies: analysis: controlling for confounding • Controlling for confounding in the analysis phase: similar to other types of studies • Outcome may be dichotomous – Presence or absence of prevalent disease – Stratified analysis of cross-sectional data (Mantel. Haenszel procedures) – Logistic regression, negative binomial regression, etc. • Outcome may be continuous – e. g. blood pressure, bone mineral density – Linear regression

Cross-sectional studies: analysis: controlling for confounding • Vulnerable to residual confounding • Interpretation is dependent on crosssectional design – Timing of exposure relative to disease – Characteristics of prevalent cases • Information available about disease onset

Cross-sectional studies: serologic studies • Blood samples from: – General population – Target sub-population (e. g. military recruits, college students) • Antigen type, antibodies, immune complexes, various biochemical components, genetic characteristics (blood group, HLA antigens, etc. )

Cross-sectional studies: serologic studies • Seroepidemiology: – Different from diagnostic testing (this is performed in individuals with some disease) – Applied to population groups • Usually healthy • Determine current and past patterns of infection and disease – Can analyze serological results in relation to other data (questionnaire items, etc. )

Cross-sectional studies: seroepidemiology • Antibody prevalence reflects exposures during certain time period – Ig. G antibodies normally last a lifetime • Cumulative experience of the population since birth – Ig. M antibodies: shorter duration • Proportion of population infected during last few months

Cross-sectional studies: seroepidemiology: possible uses • Determine prevalence: – Presence of antibody, antigen, chemical, hormone, etc. – (Need at least 2 timepoints to determine incidence) • Diagnostic serology: – Identification of various causes of a clinical syndrome – Identification of the spectrum of disease associated with a single causal agent or risk factor • Identify an association between 2 or more markers

Ecologic studies • Unit of analysis is a group of individuals – Defined by geography, time period, etc. – Usually depends on available data – Disease information from health agencies for geographic units (country, state, county, etc. ) – Exposure information from another agency that tracks industries, farming techniques, food sales, etc. • Question: do areas with high exposure have the highest rates of disease?

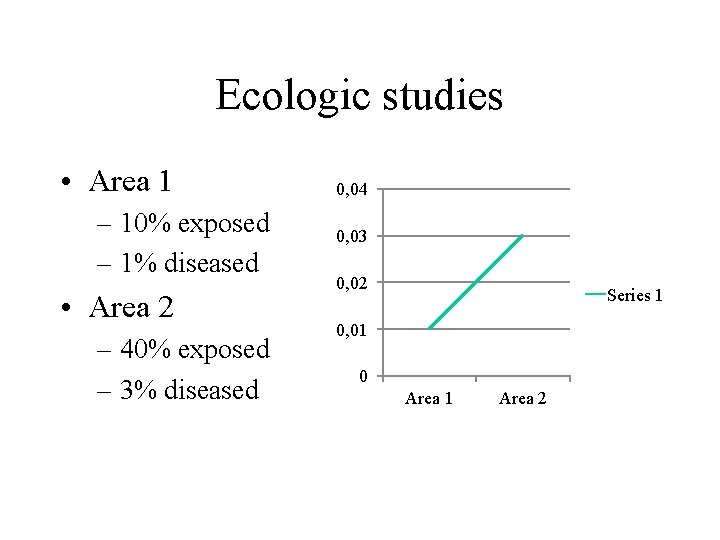

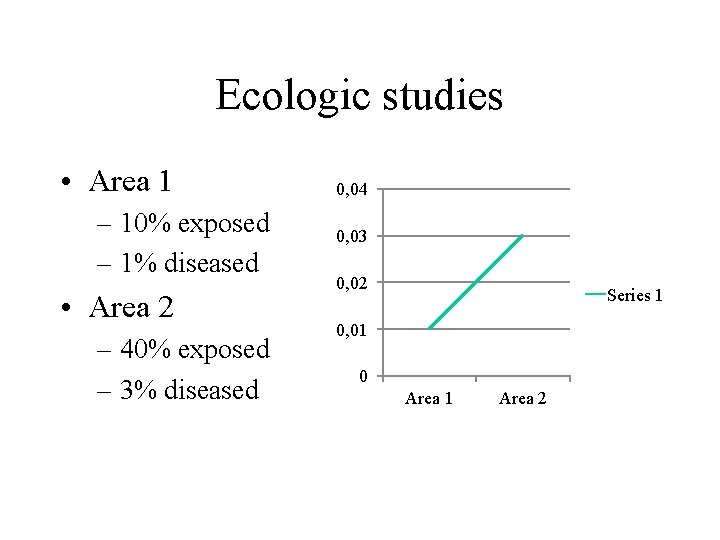

Ecologic studies • Area 1 – 10% exposed – 1% diseased • Area 2 – 40% exposed – 3% diseased 0, 04 0, 03 0, 02 Series 1 0, 01 0 Area 1 Area 2

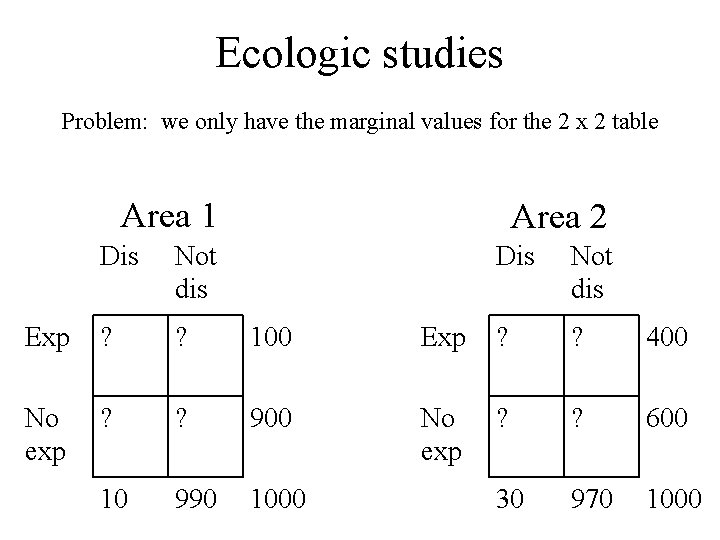

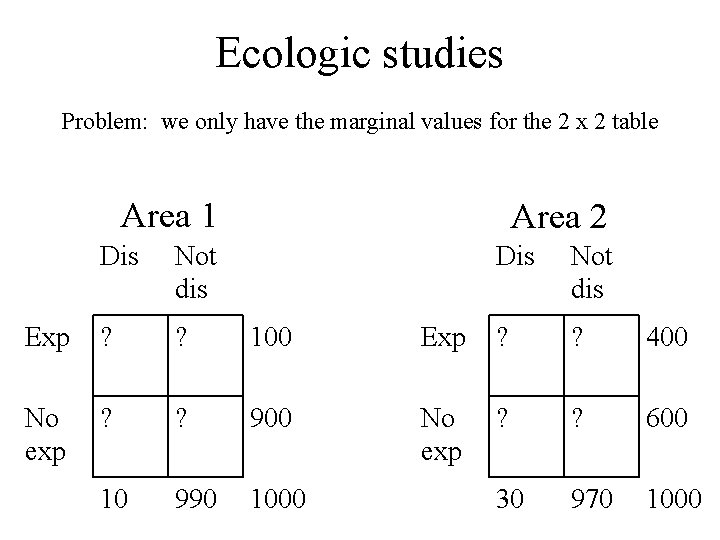

Ecologic studies Problem: we only have the marginal values for the 2 x 2 table Area 1 Area 2 Dis Not dis Exp ? ? 100 No exp ? ? 900 10 990 1000 Dis Not dis Exp ? ? 400 No exp ? ? 600 30 970 1000

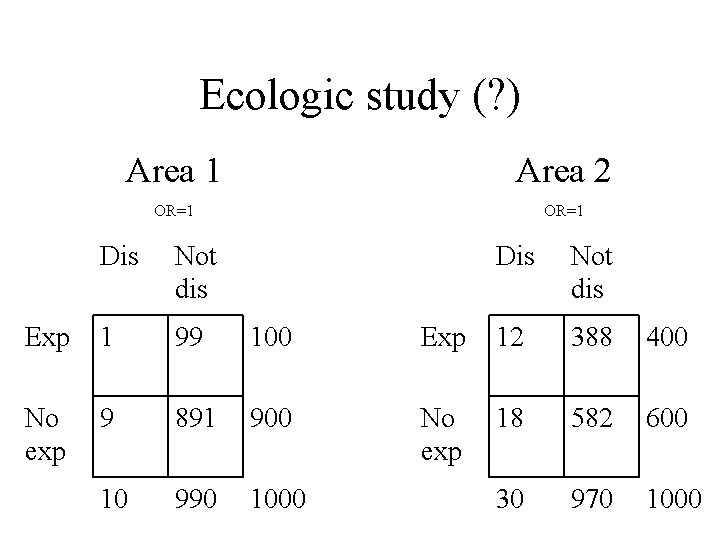

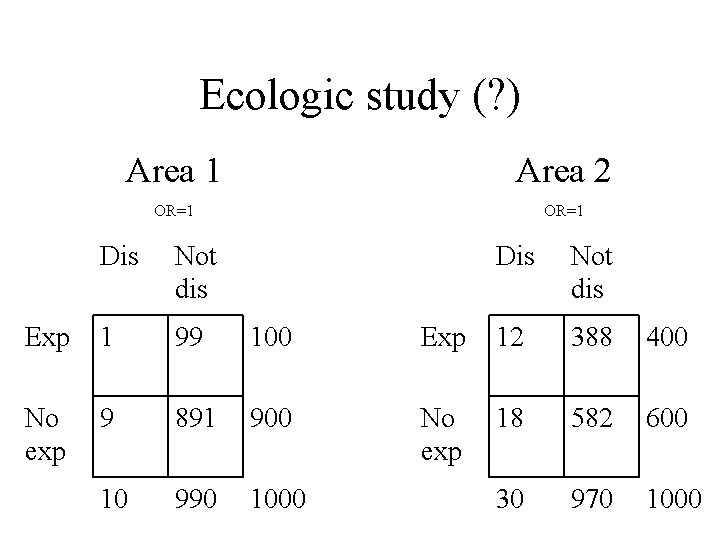

Ecologic study (? ) Area 1 Area 2 OR=1 Dis Not dis Exp 1 99 100 No exp 9 891 900 10 990 1000 Dis Not dis Exp 12 388 400 No exp 18 582 600 30 970 1000

Ecologic study (? ) Area 1 Area 2 OR=1 OR=0. 22 Dis Not dis Exp 1 99 100 No exp 9 891 900 10 990 1000 Dis Not dis Exp 4 396 400 No exp 26 574 600 30 970 1000

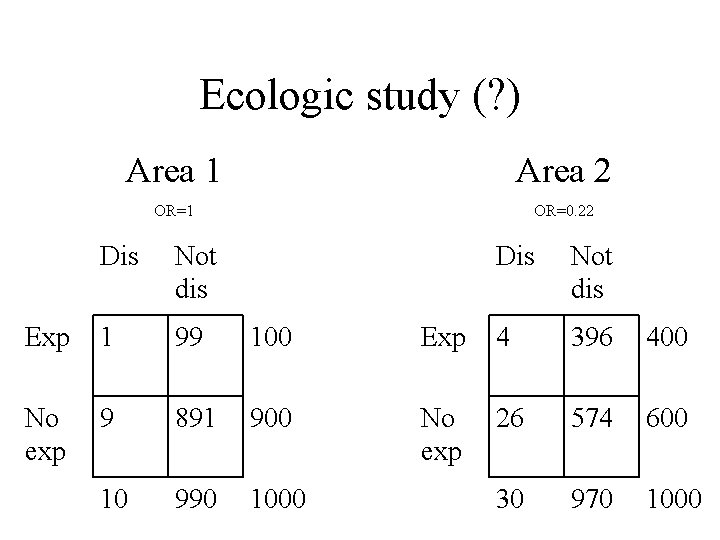

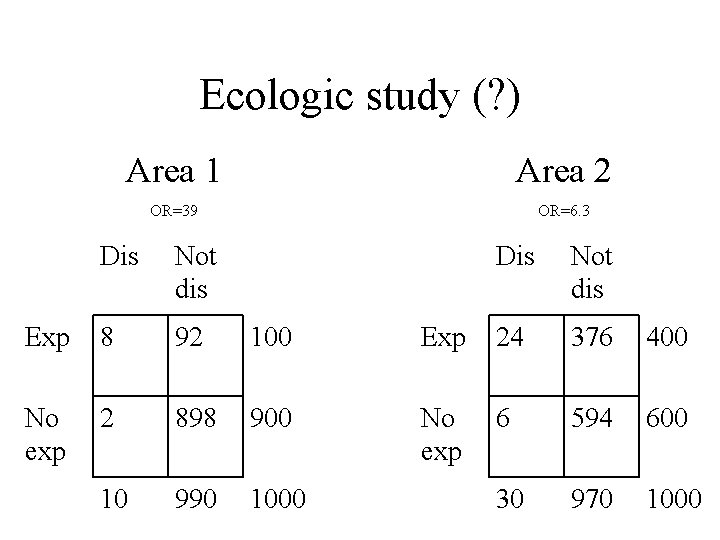

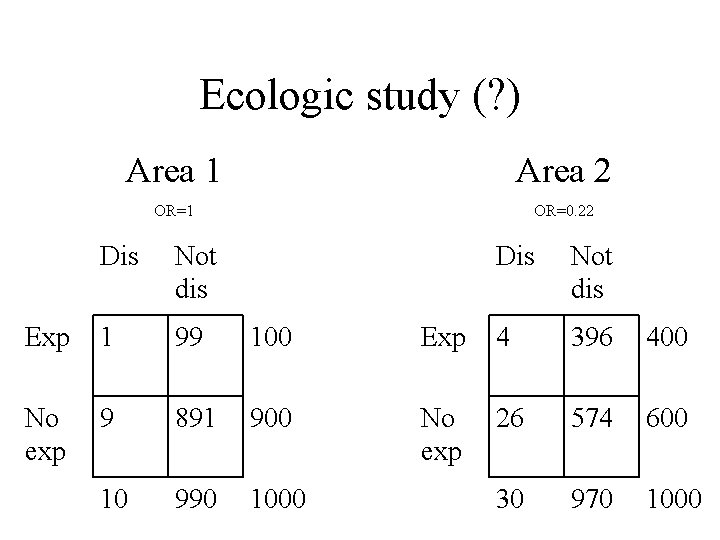

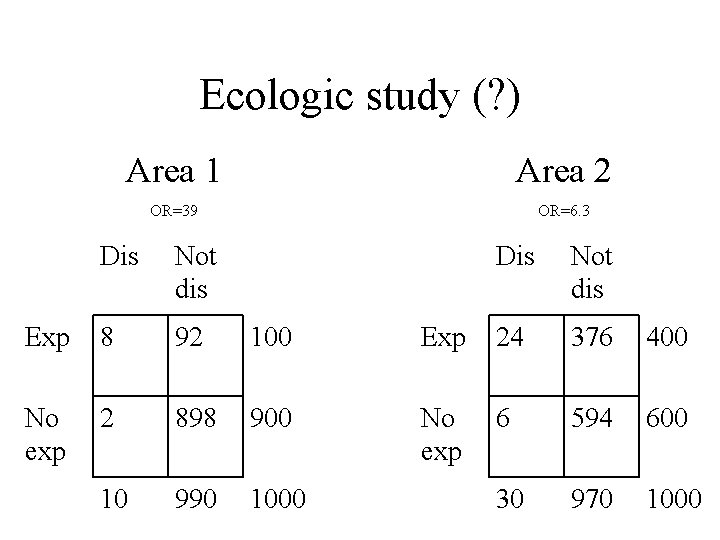

Ecologic study (? ) Area 1 Area 2 OR=39 OR=6. 3 Dis Not dis Exp 8 92 100 No exp 2 898 900 10 990 1000 Dis Not dis Exp 24 376 400 No exp 6 594 600 30 970 1000

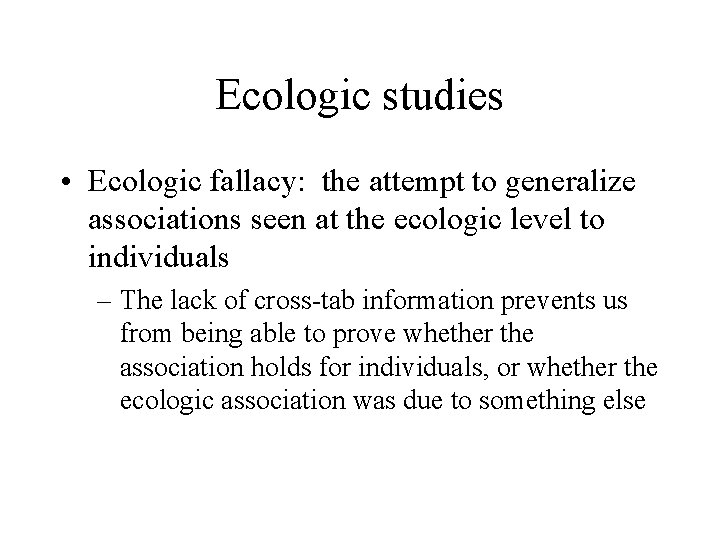

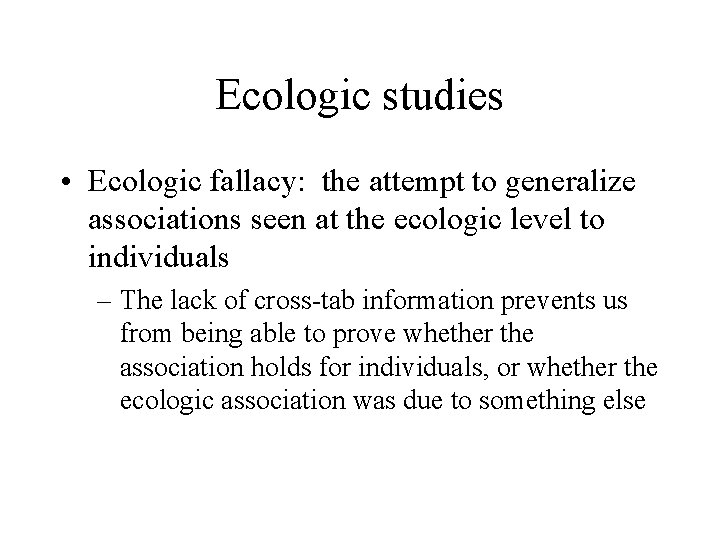

Ecologic studies • Ecologic fallacy: the attempt to generalize associations seen at the ecologic level to individuals – The lack of cross-tab information prevents us from being able to prove whether the association holds for individuals, or whether the ecologic association was due to something else

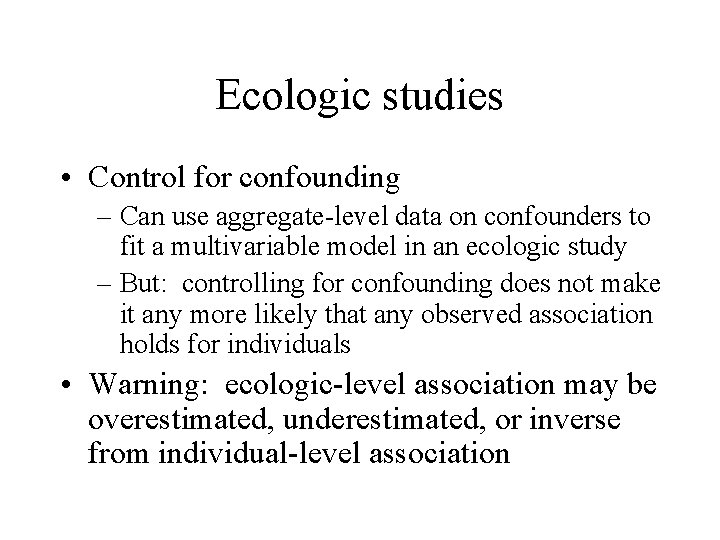

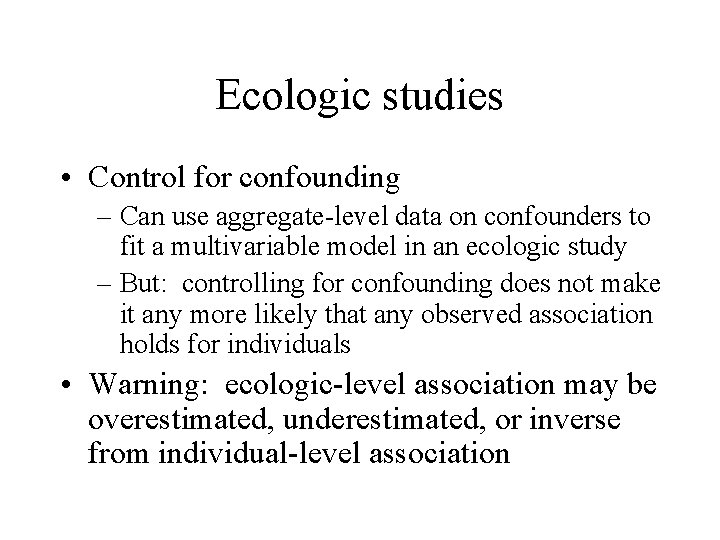

Ecologic studies • Control for confounding – Can use aggregate-level data on confounders to fit a multivariable model in an ecologic study – But: controlling for confounding does not make it any more likely that any observed association holds for individuals • Warning: ecologic-level association may be overestimated, underestimated, or inverse from individual-level association

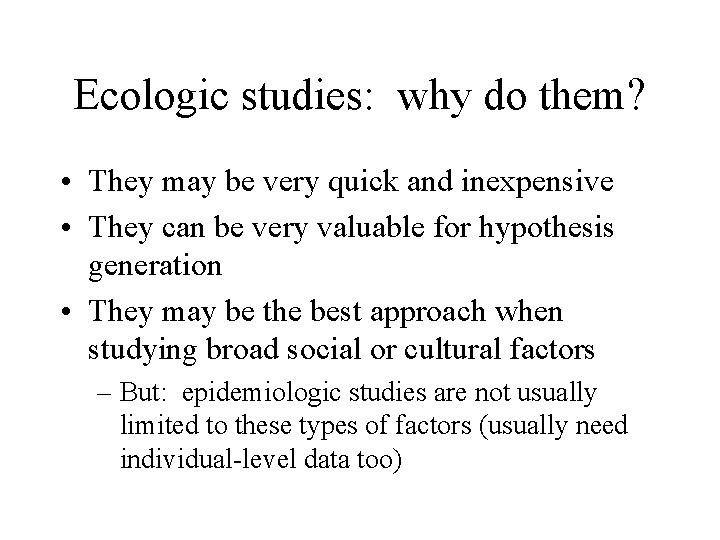

Ecologic studies: why do them? • They may be very quick and inexpensive • They can be very valuable for hypothesis generation • They may be the best approach when studying broad social or cultural factors – But: epidemiologic studies are not usually limited to these types of factors (usually need individual-level data too)