Lecture 11 n Circuits for floatingpoint operations addition

- Slides: 34

Lecture 11 n Circuits for floating-point operations addition multiplication division (only sketchy) Oct 12

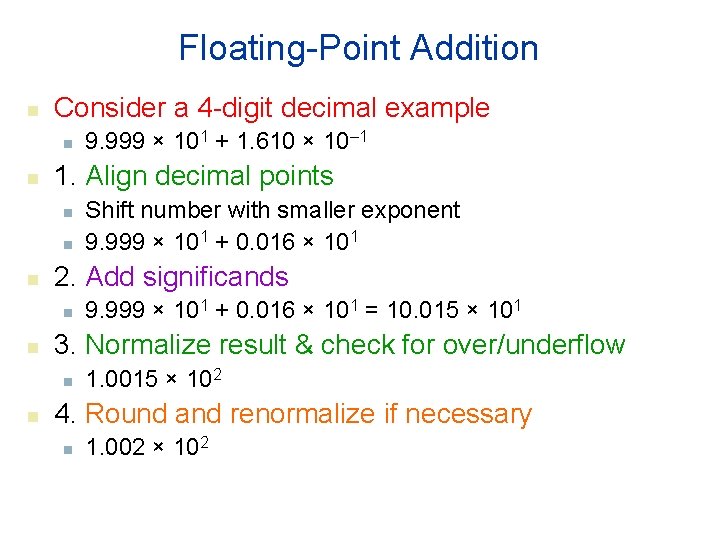

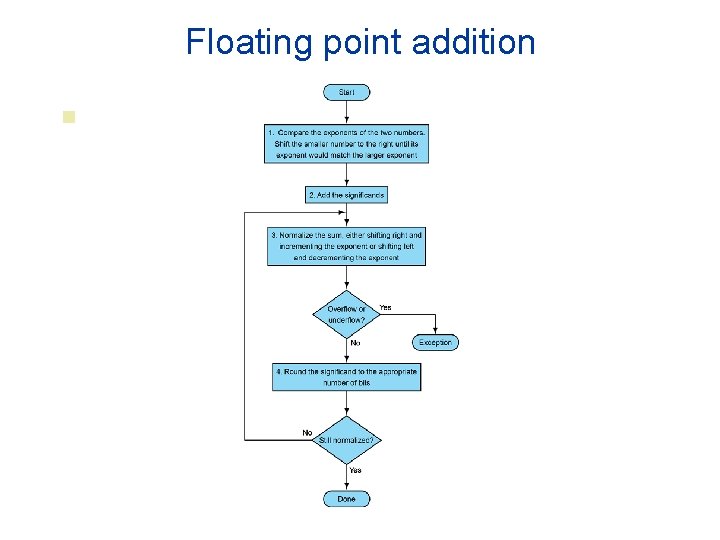

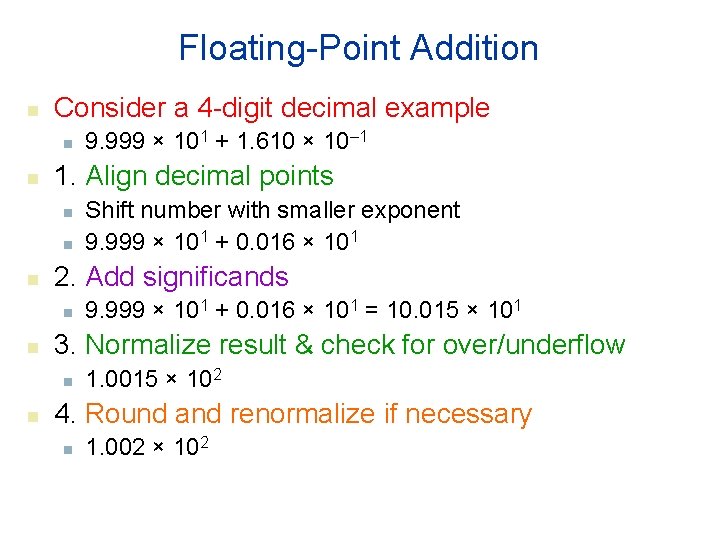

Floating-Point Addition n Consider a 4 -digit decimal example n n 1. Align decimal points n n n 9. 999 × 101 + 0. 016 × 101 = 10. 015 × 101 3. Normalize result & check for over/underflow n n Shift number with smaller exponent 9. 999 × 101 + 0. 016 × 101 2. Add significands n n 9. 999 × 101 + 1. 610 × 10– 1 1. 0015 × 102 4. Round and renormalize if necessary n 1. 002 × 102

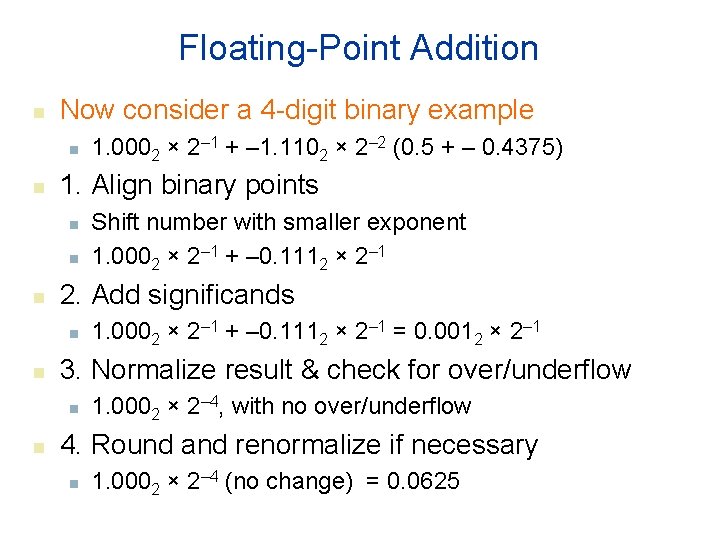

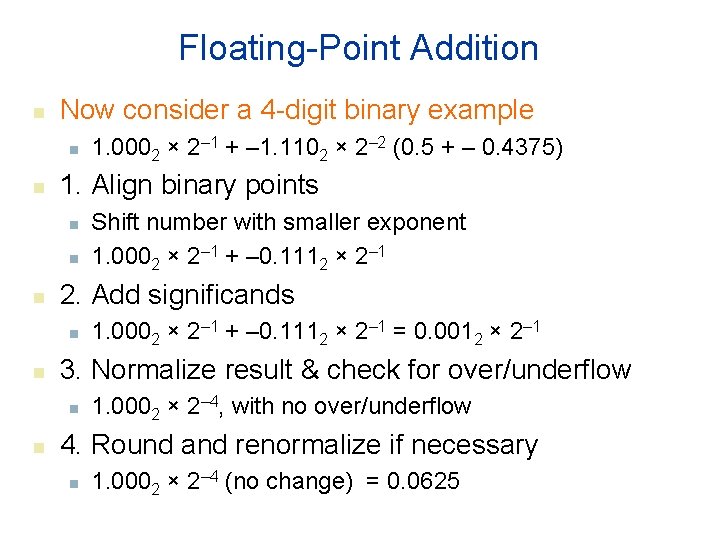

Floating-Point Addition n Now consider a 4 -digit binary example n n 1. Align binary points n n n 1. 0002 × 2– 1 + – 0. 1112 × 2– 1 = 0. 0012 × 2– 1 3. Normalize result & check for over/underflow n n Shift number with smaller exponent 1. 0002 × 2– 1 + – 0. 1112 × 2– 1 2. Add significands n n 1. 0002 × 2– 1 + – 1. 1102 × 2– 2 (0. 5 + – 0. 4375) 1. 0002 × 2– 4, with no over/underflow 4. Round and renormalize if necessary n 1. 0002 × 2– 4 (no change) = 0. 0625

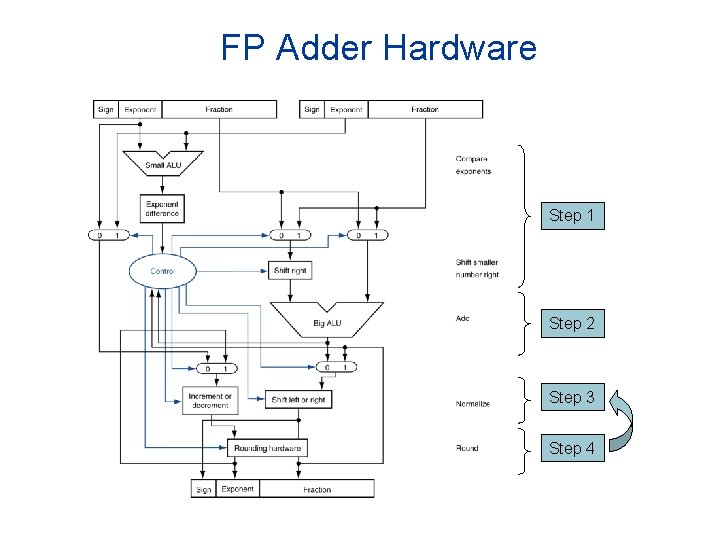

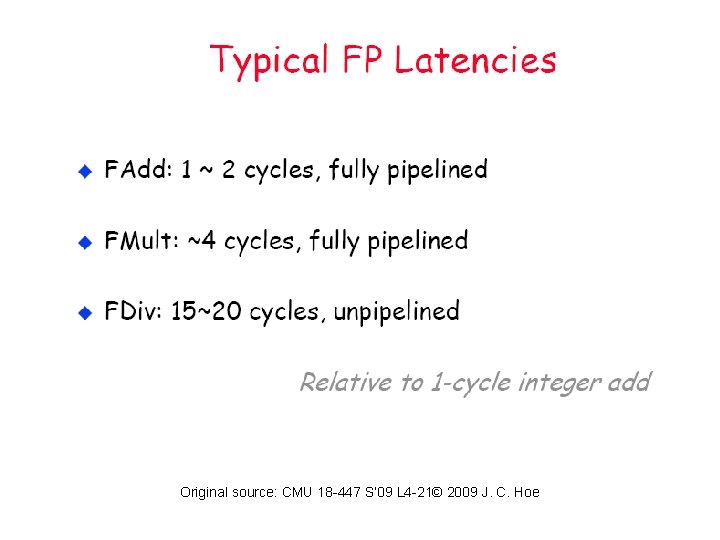

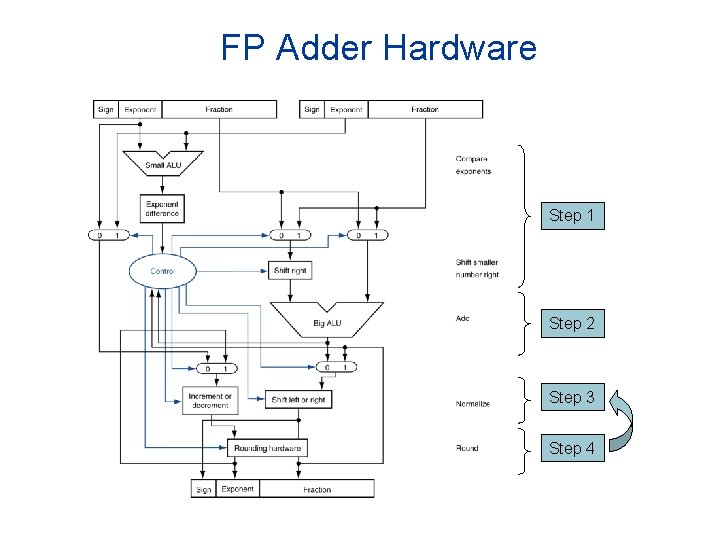

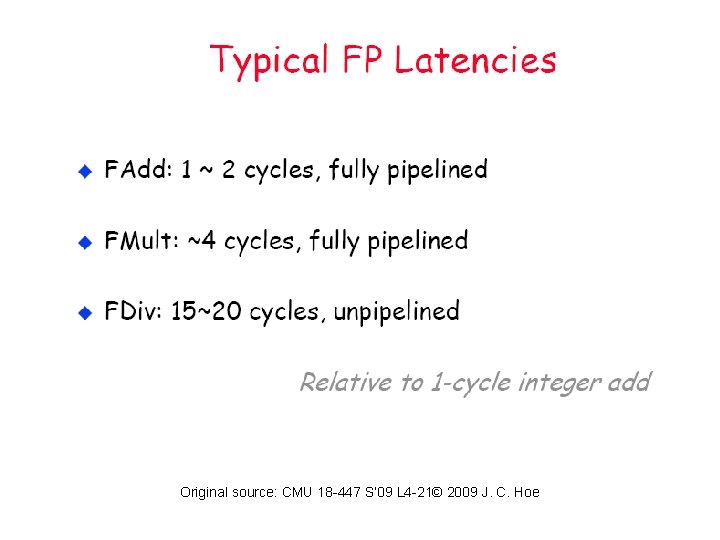

FP Adder Hardware n n Much more complex than integer adder Doing it in one clock cycle would take too long n n n Much longer than integer operations Slower clock would penalize all instructions FP adder usually takes several cycles n Can be pipelined

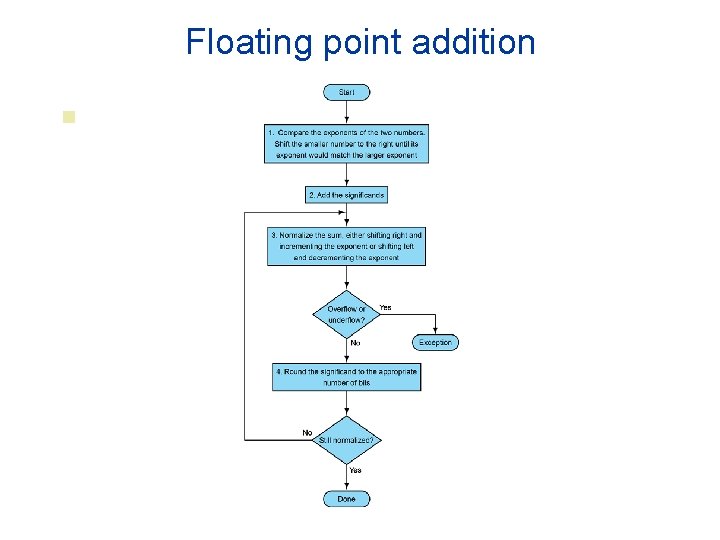

Floating point addition n

FP Adder Hardware Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4

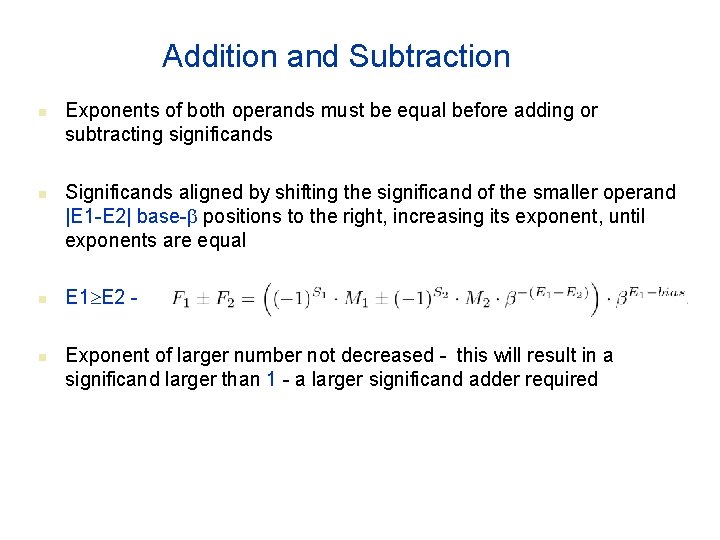

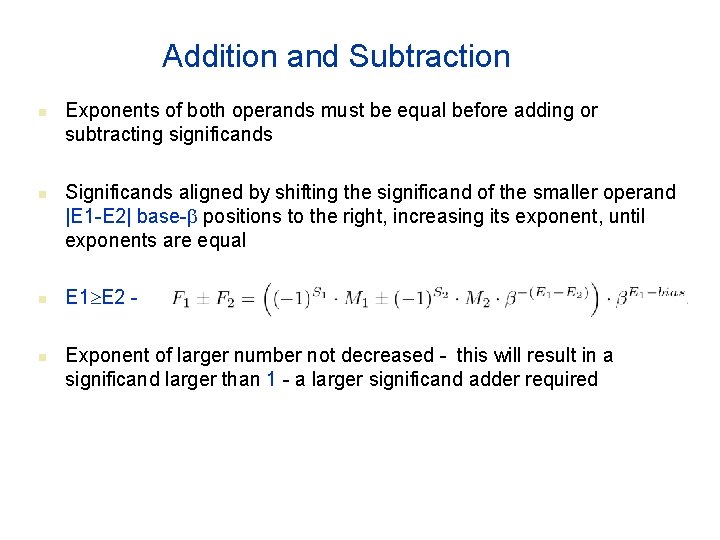

Addition and Subtraction n n Exponents of both operands must be equal before adding or subtracting significands Significands aligned by shifting the significand of the smaller operand |E 1 -E 2| base- positions to the right, increasing its exponent, until exponents are equal E 1 E 2 Exponent of larger number not decreased - this will result in a significand larger than 1 - a larger significand adder required

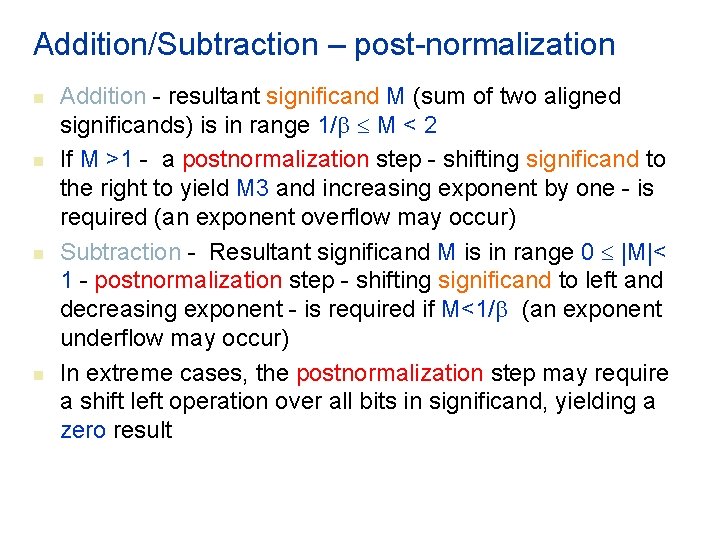

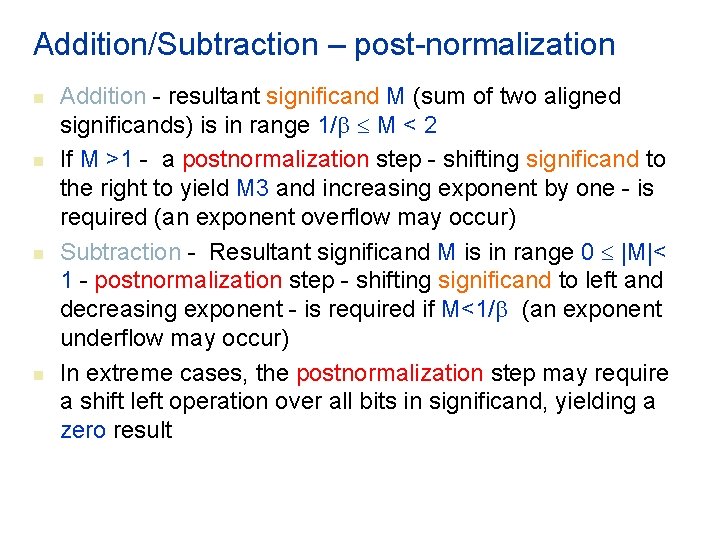

Addition/Subtraction – post-normalization n n Addition - resultant significand M (sum of two aligned significands) is in range 1/ M < 2 If M >1 - a postnormalization step - shifting significand to the right to yield M 3 and increasing exponent by one - is required (an exponent overflow may occur) Subtraction - Resultant significand M is in range 0 |M|< 1 - postnormalization step - shifting significand to left and decreasing exponent - is required if M<1/ (an exponent underflow may occur) In extreme cases, the postnormalization step may require a shift left operation over all bits in significand, yielding a zero result

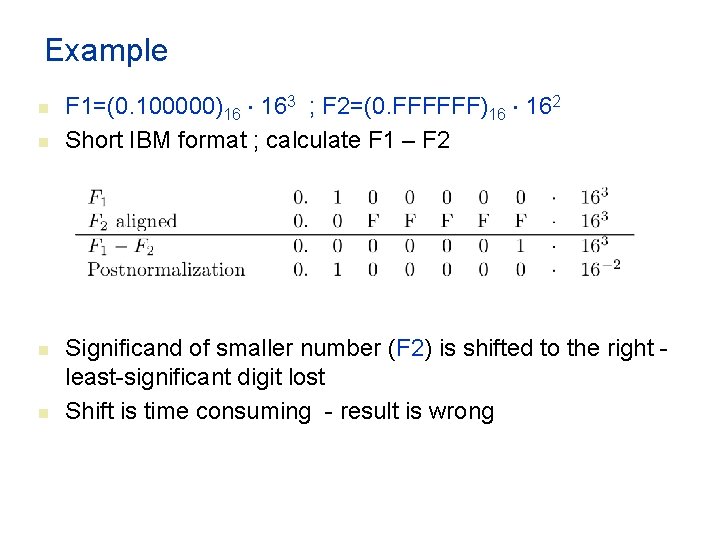

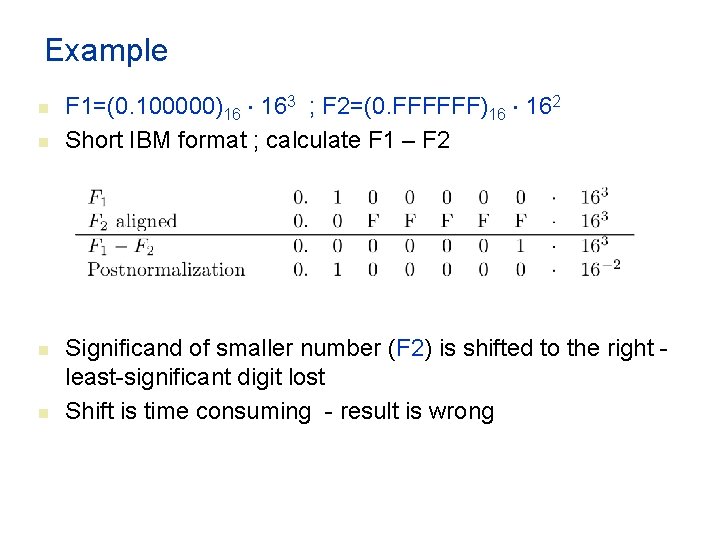

Example n n F 1=(0. 100000)16 163 ; F 2=(0. FFFFFF)16 162 Short IBM format ; calculate F 1 – F 2 Significand of smaller number (F 2) is shifted to the right least-significant digit lost Shift is time consuming - result is wrong

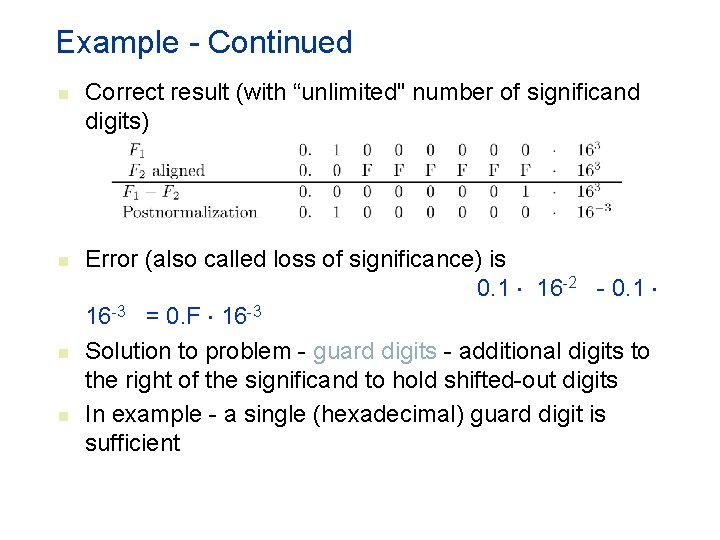

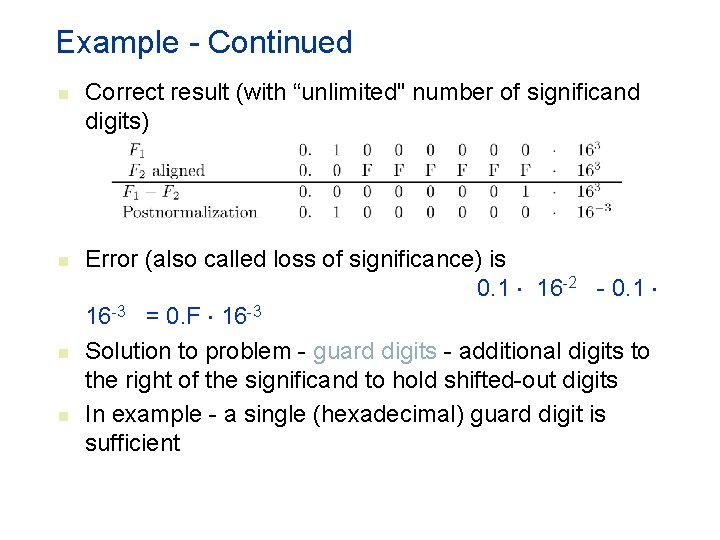

Example - Continued n n Correct result (with “unlimited" number of significand digits) Error (also called loss of significance) is 0. 1 16 -2 - 0. 1 16 -3 = 0. F 16 -3 Solution to problem - guard digits - additional digits to the right of the significand to hold shifted-out digits In example - a single (hexadecimal) guard digit is sufficient

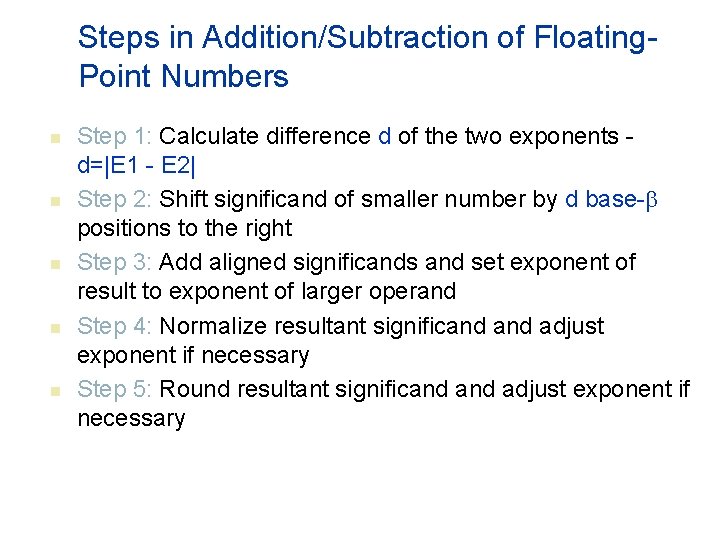

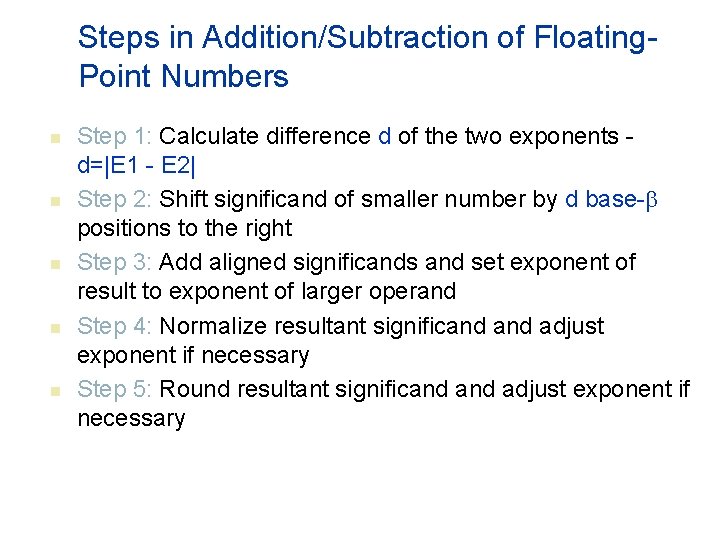

Steps in Addition/Subtraction of Floating. Point Numbers n n n Step 1: Calculate difference d of the two exponents d=|E 1 - E 2| Step 2: Shift significand of smaller number by d base- positions to the right Step 3: Add aligned significands and set exponent of result to exponent of larger operand Step 4: Normalize resultant significand adjust exponent if necessary Step 5: Round resultant significand adjust exponent if necessary

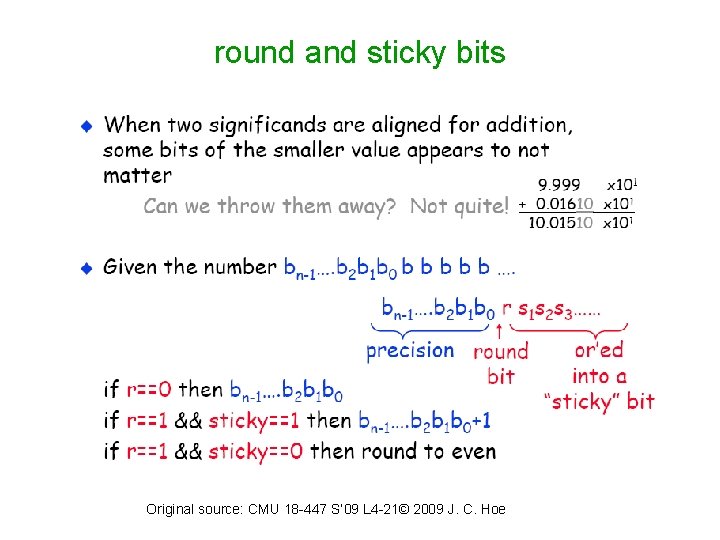

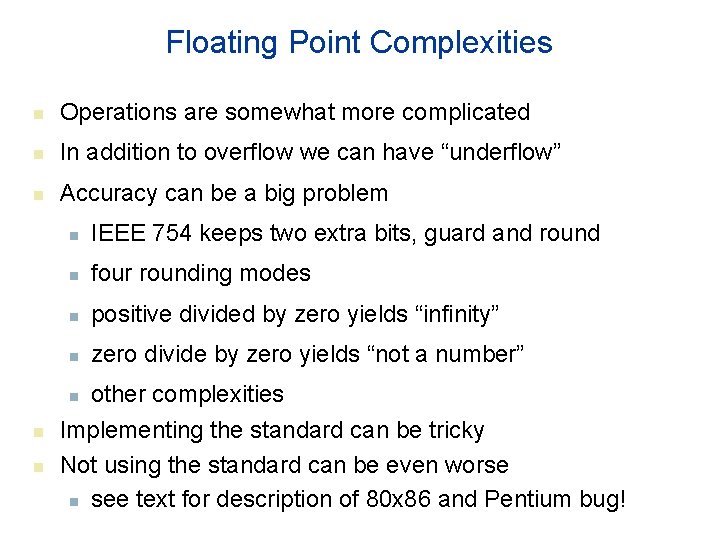

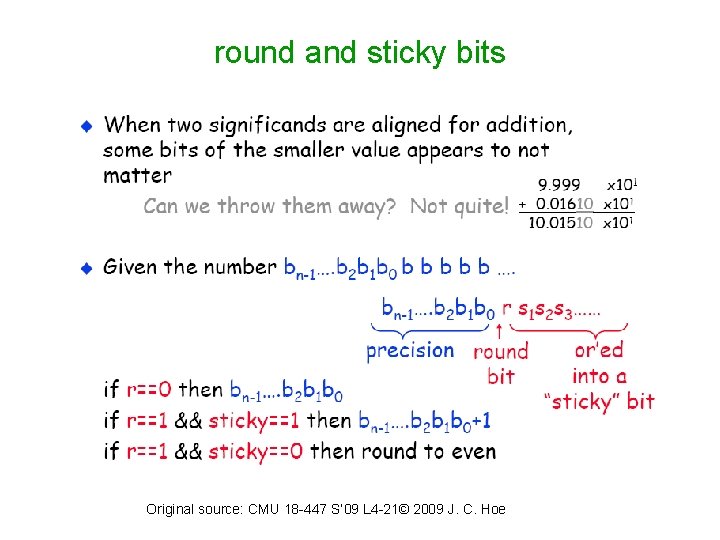

Floating Point Complexities n Operations are somewhat more complicated n In addition to overflow we can have “underflow” n Accuracy can be a big problem n IEEE 754 keeps two extra bits, guard and round n four rounding modes n positive divided by zero yields “infinity” n zero divide by zero yields “not a number” other complexities Implementing the standard can be tricky Not using the standard can be even worse n see text for description of 80 x 86 and Pentium bug! n n n

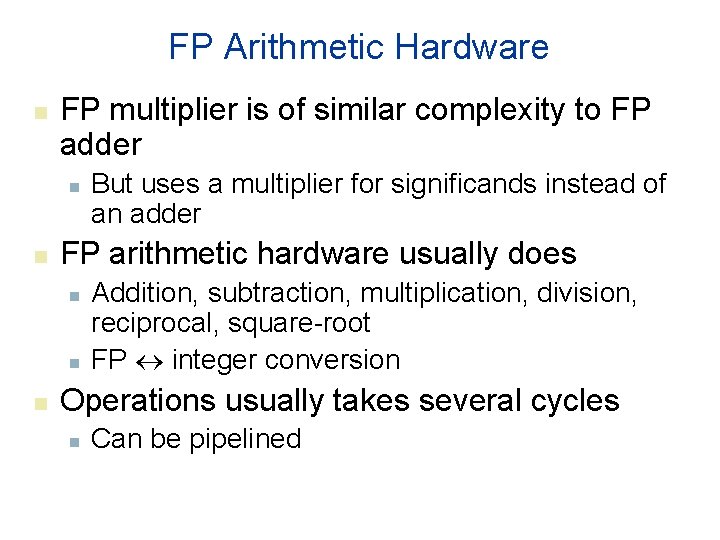

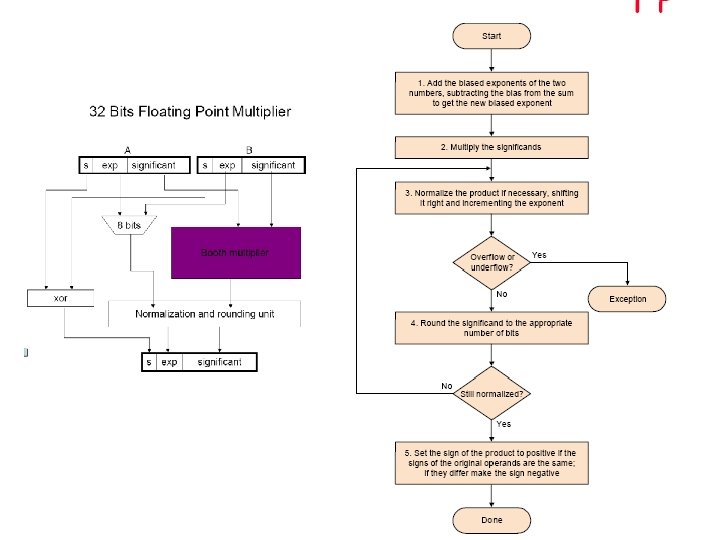

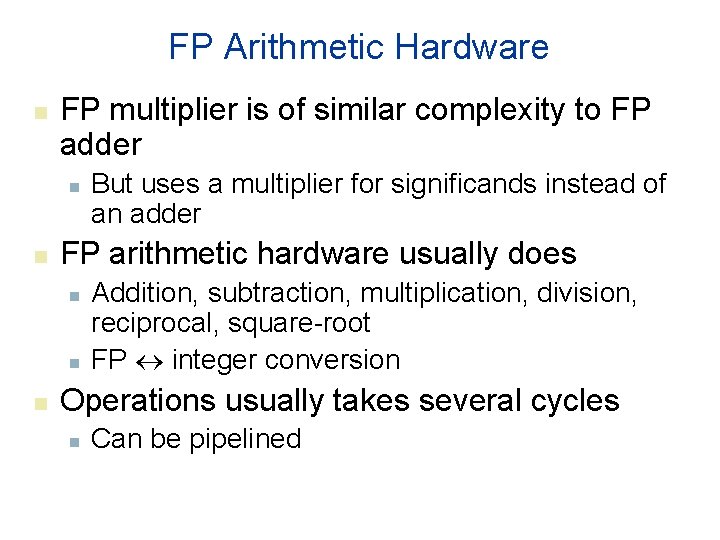

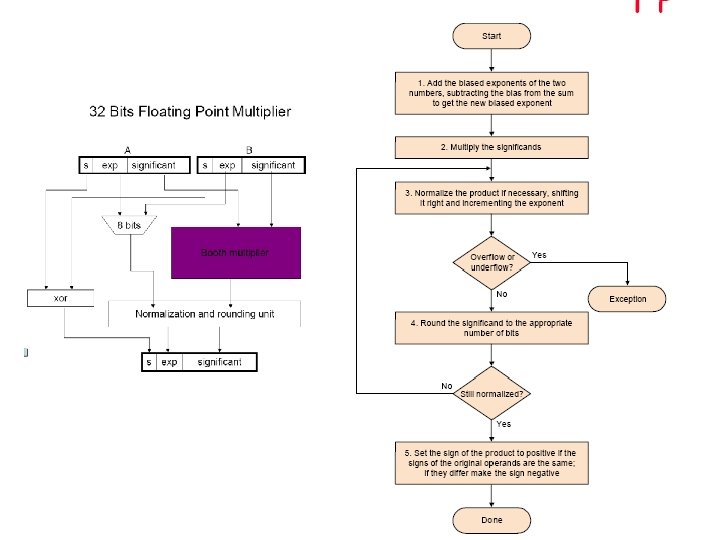

FP Arithmetic Hardware n FP multiplier is of similar complexity to FP adder n n FP arithmetic hardware usually does n n n But uses a multiplier for significands instead of an adder Addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, reciprocal, square-root FP integer conversion Operations usually takes several cycles n Can be pipelined

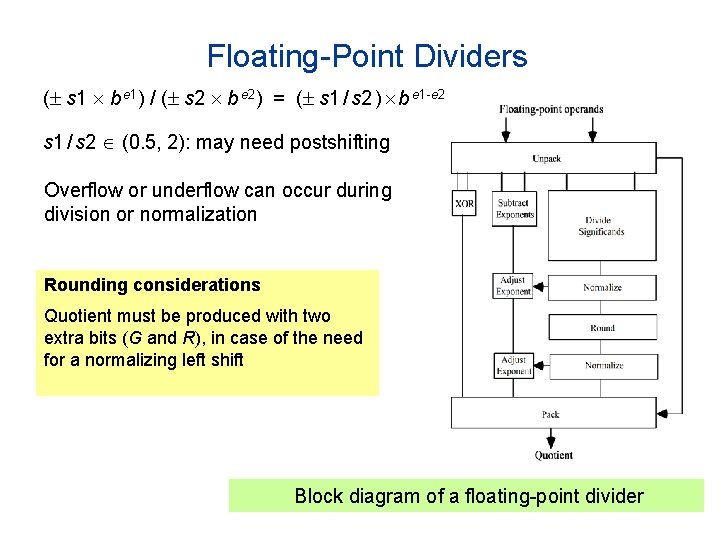

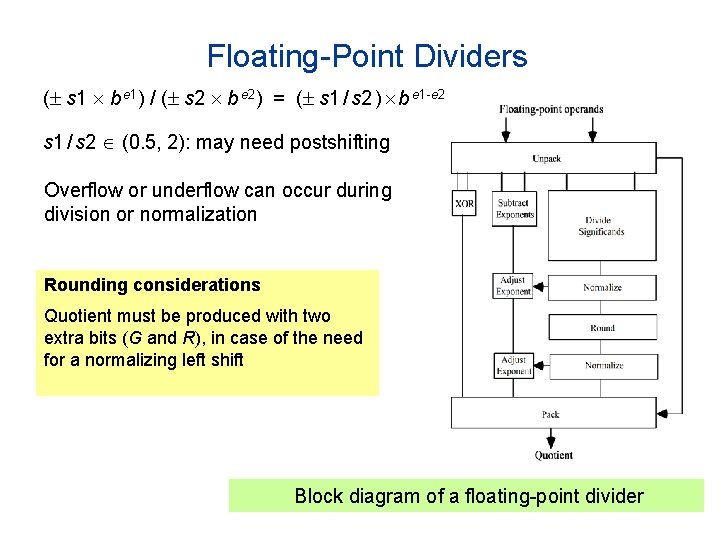

Floating-Point Dividers ( s 1 b e 1) / ( s 2 b e 2) = ( s 1 / s 2 ) b e 1 -e 2 s 1 / s 2 (0. 5, 2): may need postshifting Overflow or underflow can occur during division or normalization Rounding considerations Quotient must be produced with two extra bits (G and R), in case of the need for a normalizing left shift Block diagram of a floating-point divider

round and sticky bits Original source: CMU 18 -447 S’ 09 L 4 -21© 2009 J. C. Hoe

Original source: CMU 18 -447 S’ 09 L 4 -21© 2009 J. C. Hoe

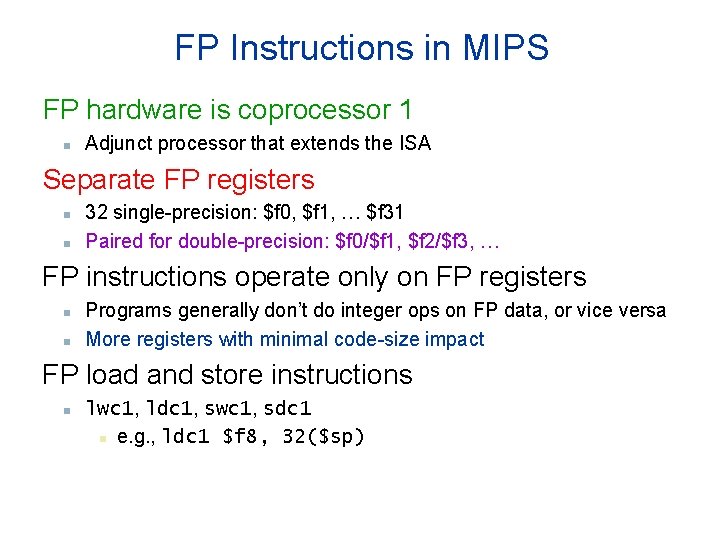

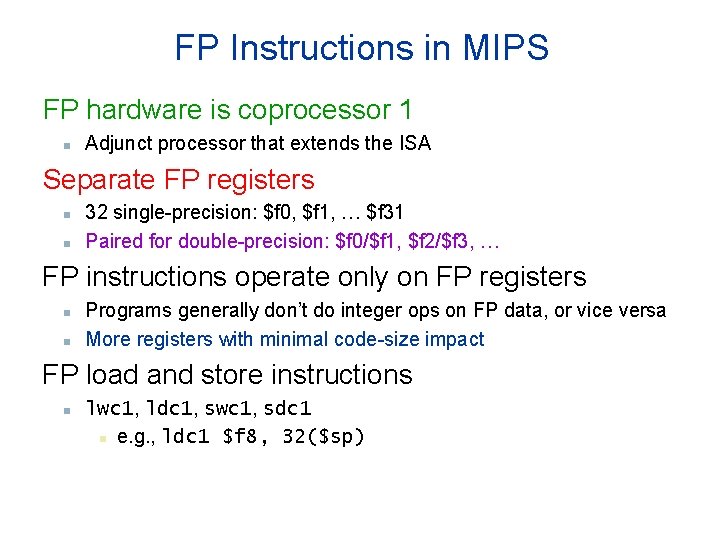

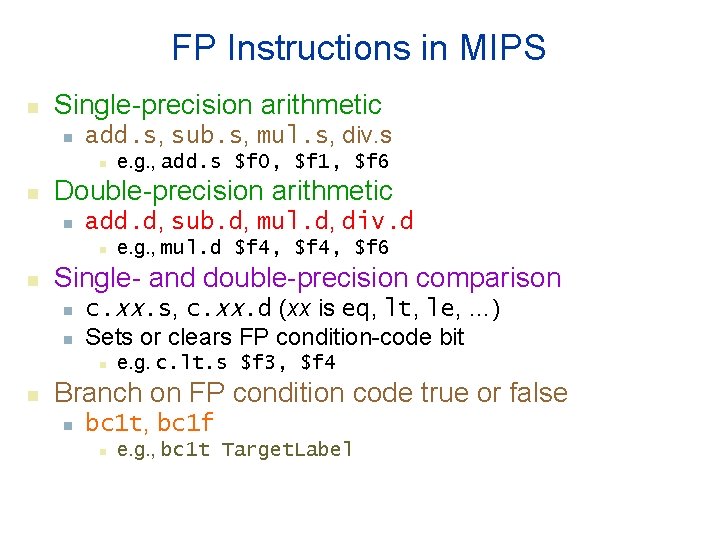

FP Instructions in MIPS FP hardware is coprocessor 1 n Adjunct processor that extends the ISA Separate FP registers n n 32 single-precision: $f 0, $f 1, … $f 31 Paired for double-precision: $f 0/$f 1, $f 2/$f 3, … FP instructions operate only on FP registers n n Programs generally don’t do integer ops on FP data, or vice versa More registers with minimal code-size impact FP load and store instructions n lwc 1, ldc 1, swc 1, sdc 1 n e. g. , ldc 1 $f 8, 32($sp)

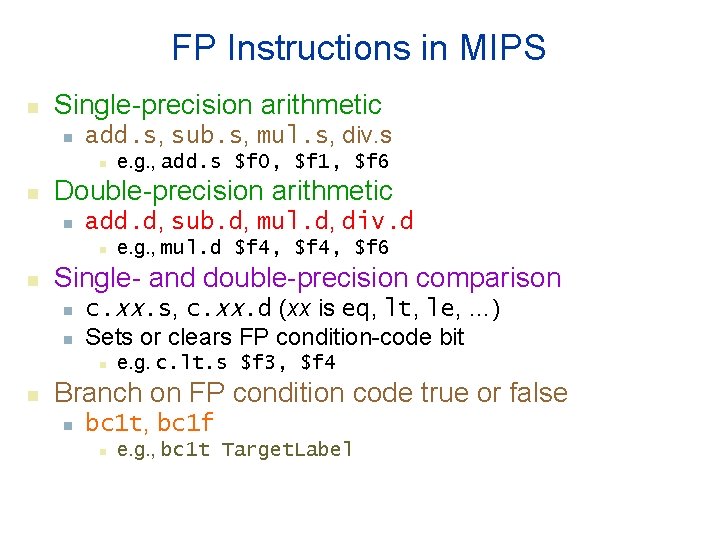

FP Instructions in MIPS n Single-precision arithmetic n add. s, sub. s, mul. s, div. s n n Double-precision arithmetic n add. d, sub. d, mul. d, div. d n n e. g. , mul. d $f 4, $f 6 Single- and double-precision comparison n n c. xx. s, c. xx. d (xx is eq, lt, le, …) Sets or clears FP condition-code bit n n e. g. , add. s $f 0, $f 1, $f 6 e. g. c. lt. s $f 3, $f 4 Branch on FP condition code true or false n bc 1 t, bc 1 f n e. g. , bc 1 t Target. Label

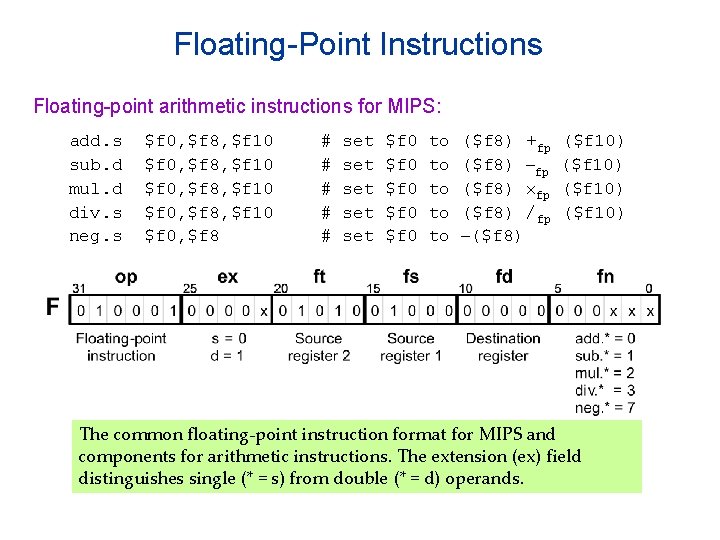

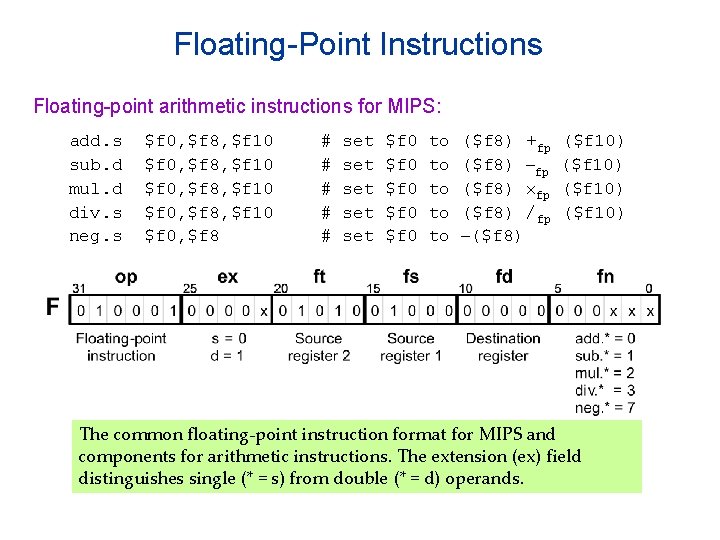

Floating-Point Instructions Floating-point arithmetic instructions for MIPS: add. s sub. d mul. d div. s neg. s $f 0, $f 8, $f 10 $f 0, $f 8 # # # set set set $f 0 $f 0 to to to ($f 8) +fp ($f 8) –fp ($f 8) /fp –($f 8) ($f 10) The common floating-point instruction format for MIPS and components for arithmetic instructions. The extension (ex) field distinguishes single (* = s) from double (* = d) operands.

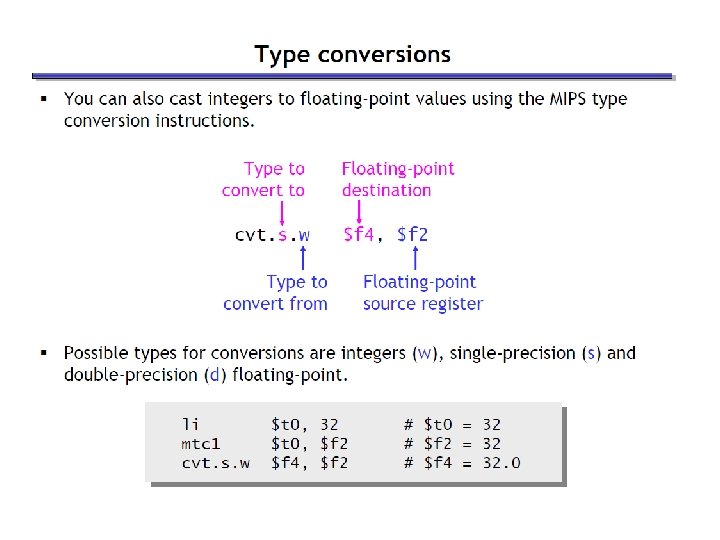

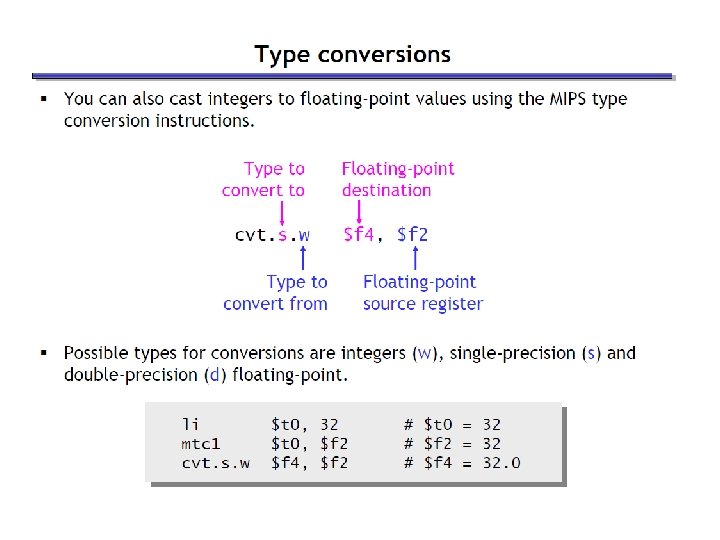

Floating-Point Format Conversions

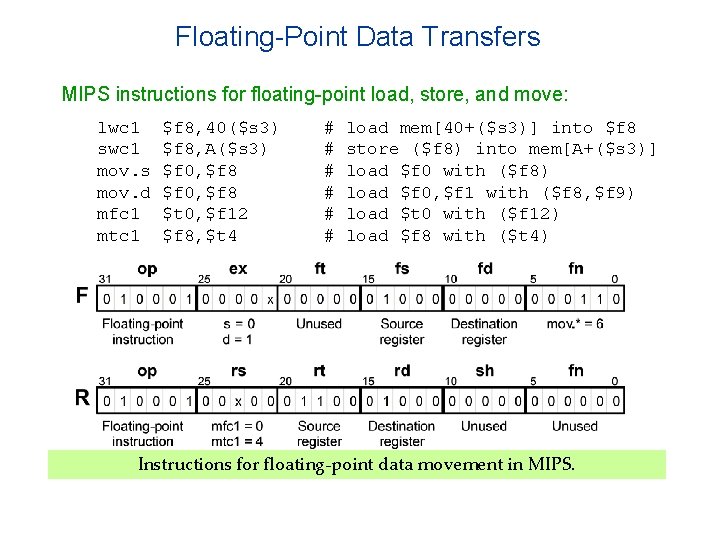

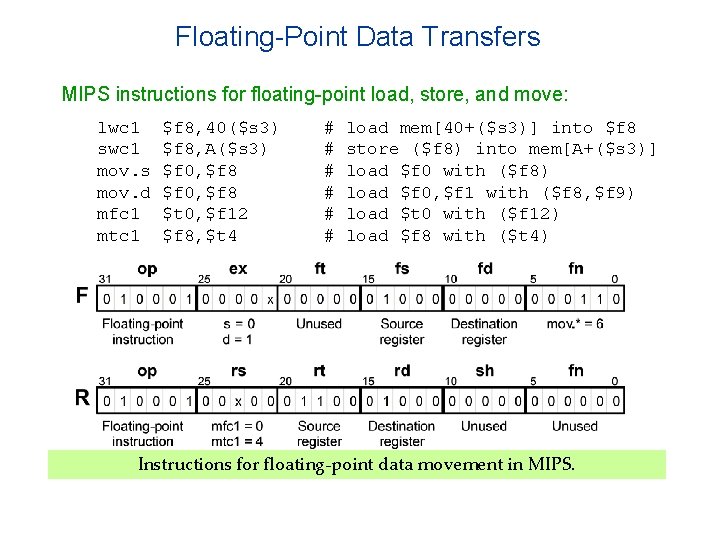

Floating-Point Data Transfers MIPS instructions for floating-point load, store, and move: lwc 1 swc 1 mov. s mov. d mfc 1 mtc 1 $f 8, 40($s 3) $f 8, A($s 3) $f 0, $f 8 $t 0, $f 12 $f 8, $t 4 # # # load mem[40+($s 3)] into $f 8 store ($f 8) into mem[A+($s 3)] load $f 0 with ($f 8) load $f 0, $f 1 with ($f 8, $f 9) load $t 0 with ($f 12) load $f 8 with ($t 4) Instructions for floating-point data movement in MIPS.

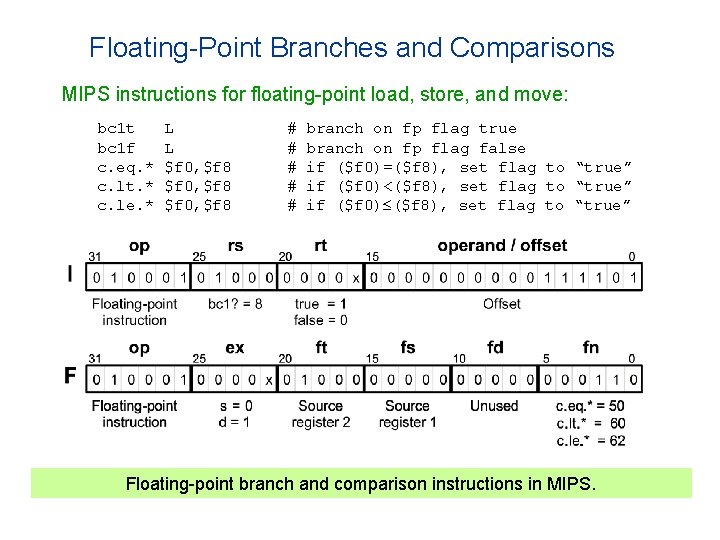

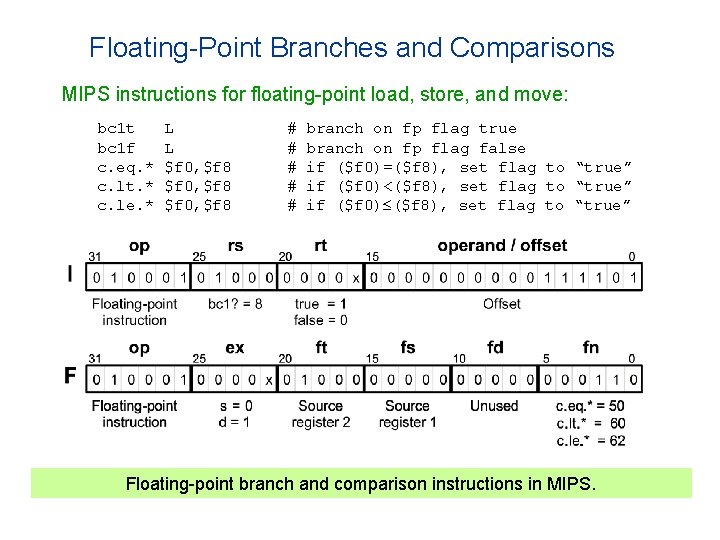

Floating-Point Branches and Comparisons MIPS instructions for floating-point load, store, and move: bc 1 t bc 1 f c. eq. * c. lt. * c. le. * L L $f 0, $f 8 # # # branch on fp flag true branch on fp flag false if ($f 0)=($f 8), set flag to “true” if ($f 0)<($f 8), set flag to “true” if ($f 0) ($f 8), set flag to “true” Floating-point branch and comparison instructions in MIPS.

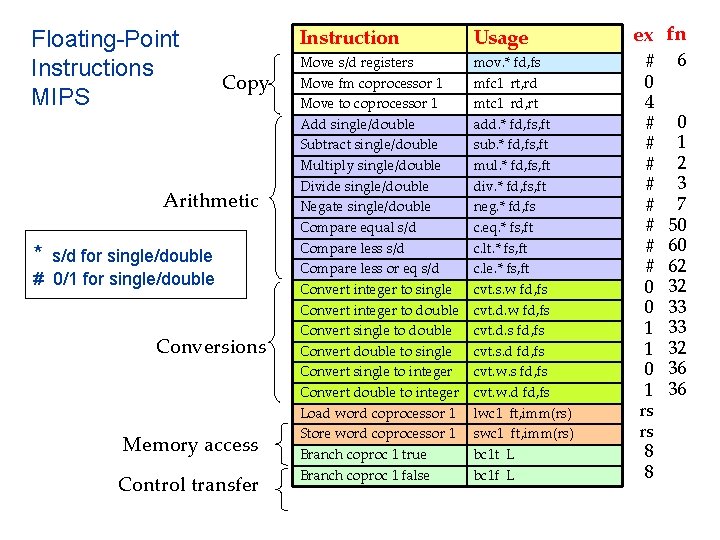

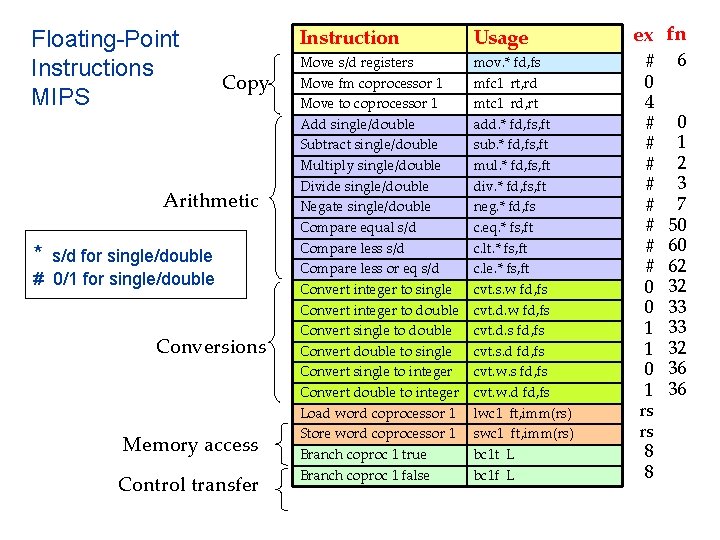

Floating-Point Instructions MIPS Copy Arithmetic * s/d for single/double # 0/1 for single/double Conversions Memory access Control transfer Instruction Usage Move s/d registers Move fm coprocessor 1 Move to coprocessor 1 Add single/double Subtract single/double Multiply single/double Divide single/double Negate single/double Compare equal s/d Compare less or eq s/d Convert integer to single Convert integer to double Convert single to double Convert double to single Convert single to integer Convert double to integer Load word coprocessor 1 Store word coprocessor 1 Branch coproc 1 true Branch coproc 1 false mov. * fd, fs mfc 1 rt, rd mtc 1 rd, rt add. * fd, fs, ft sub. * fd, fs, ft mul. * fd, fs, ft div. * fd, fs, ft neg. * fd, fs c. eq. * fs, ft c. lt. * fs, ft c. le. * fs, ft cvt. s. w fd, fs cvt. d. s fd, fs cvt. s. d fd, fs cvt. w. s fd, fs cvt. w. d fd, fs lwc 1 ft, imm(rs) swc 1 ft, imm(rs) bc 1 t L bc 1 f L ex fn # 0 4 # # # # 0 0 1 1 0 1 rs rs 8 8 6 0 1 2 3 7 50 60 62 32 33 33 32 36 36

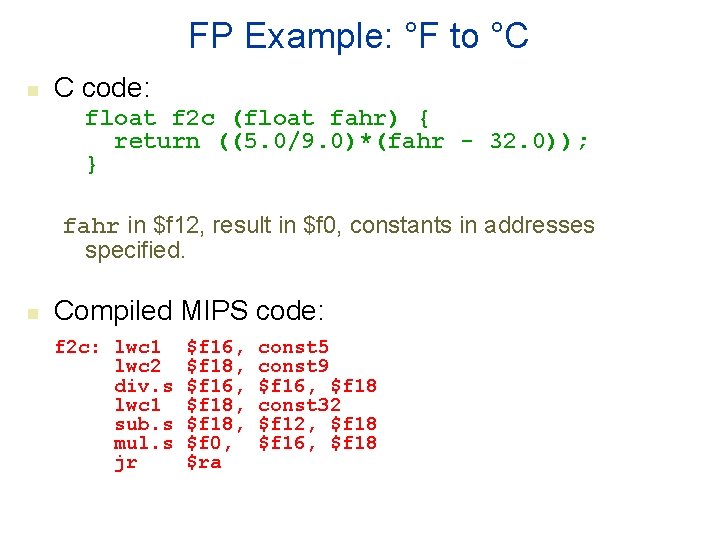

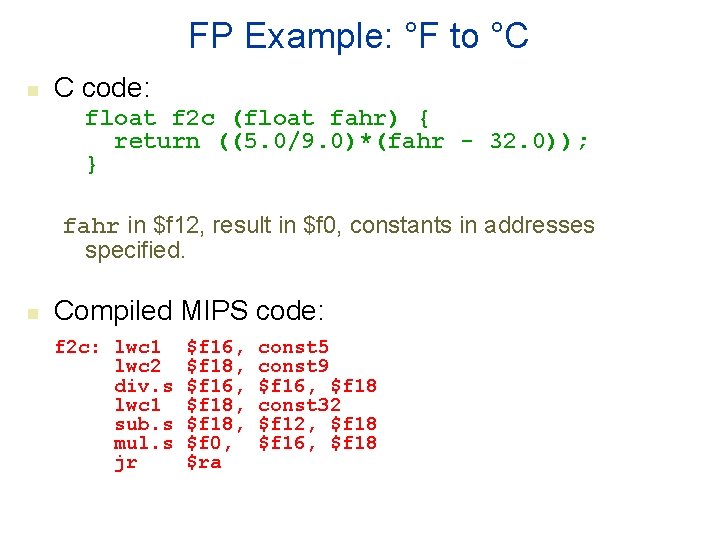

FP Example: °F to °C n C code: float f 2 c (float fahr) { return ((5. 0/9. 0)*(fahr - 32. 0)); } fahr in $f 12, result in $f 0, constants in addresses specified. n Compiled MIPS code: f 2 c: lwc 1 lwc 2 div. s lwc 1 sub. s mul. s jr $f 16, $f 18, $f 0, $ra const 5 const 9 $f 16, $f 18 const 32 $f 12, $f 18 $f 16, $f 18

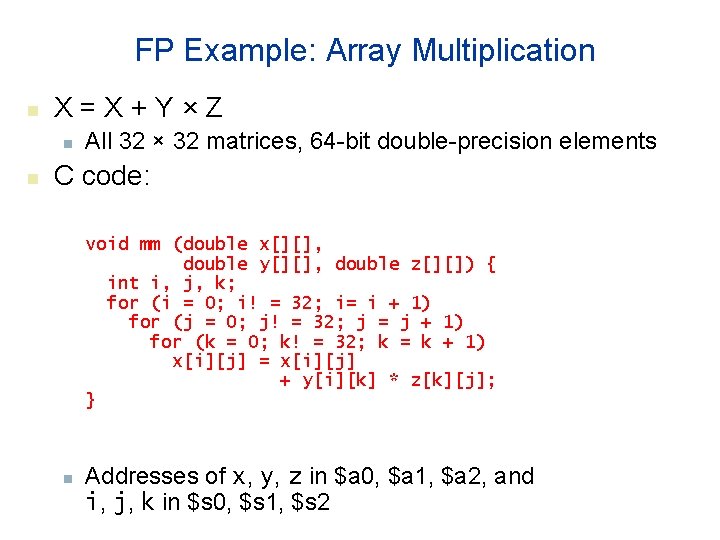

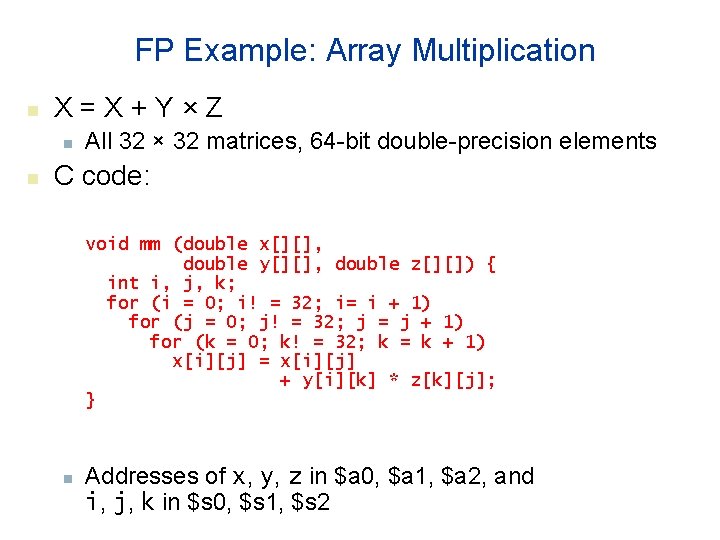

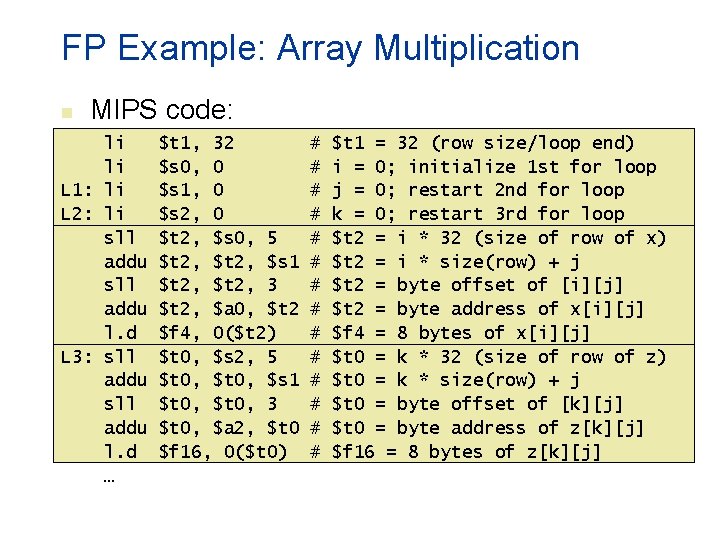

FP Example: Array Multiplication n X=X+Y×Z n n All 32 × 32 matrices, 64 -bit double-precision elements C code: void mm (double x[][], double y[][], double z[][]) { int i, j, k; for (i = 0; i! = 32; i= i + 1) for (j = 0; j! = 32; j = j + 1) for (k = 0; k! = 32; k = k + 1) x[i][j] = x[i][j] + y[i][k] * z[k][j]; } n Addresses of x, y, z in $a 0, $a 1, $a 2, and i, j, k in $s 0, $s 1, $s 2

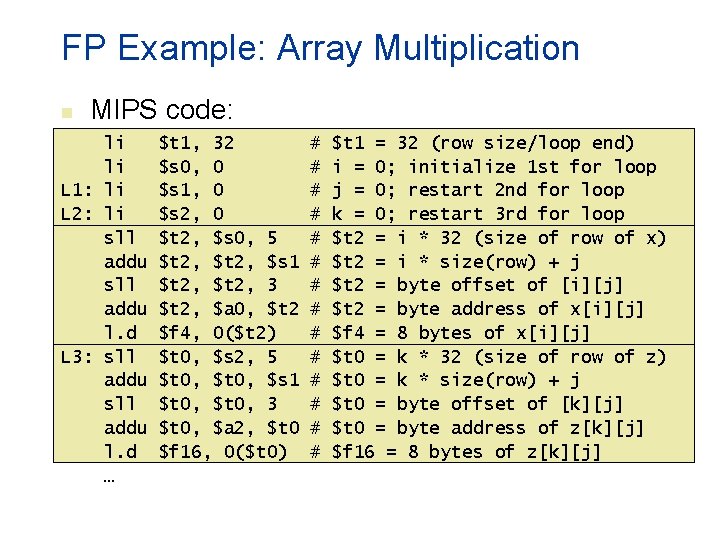

FP Example: Array Multiplication n MIPS code: li li L 1: li L 2: li sll addu l. d L 3: sll addu l. d … $t 1, 32 $s 0, 0 $s 1, 0 $s 2, 0 $t 2, $s 0, 5 $t 2, $s 1 $t 2, 3 $t 2, $a 0, $t 2 $f 4, 0($t 2) $t 0, $s 2, 5 $t 0, $s 1 $t 0, 3 $t 0, $a 2, $t 0 $f 16, 0($t 0) # # # # $t 1 = 32 (row size/loop end) i = 0; initialize 1 st for loop j = 0; restart 2 nd for loop k = 0; restart 3 rd for loop $t 2 = i * 32 (size of row of x) $t 2 = i * size(row) + j $t 2 = byte offset of [i][j] $t 2 = byte address of x[i][j] $f 4 = 8 bytes of x[i][j] $t 0 = k * 32 (size of row of z) $t 0 = k * size(row) + j $t 0 = byte offset of [k][j] $t 0 = byte address of z[k][j] $f 16 = 8 bytes of z[k][j]

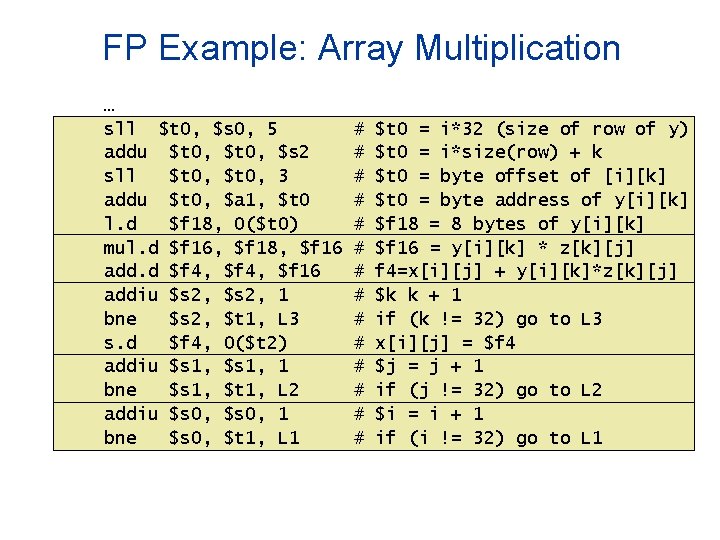

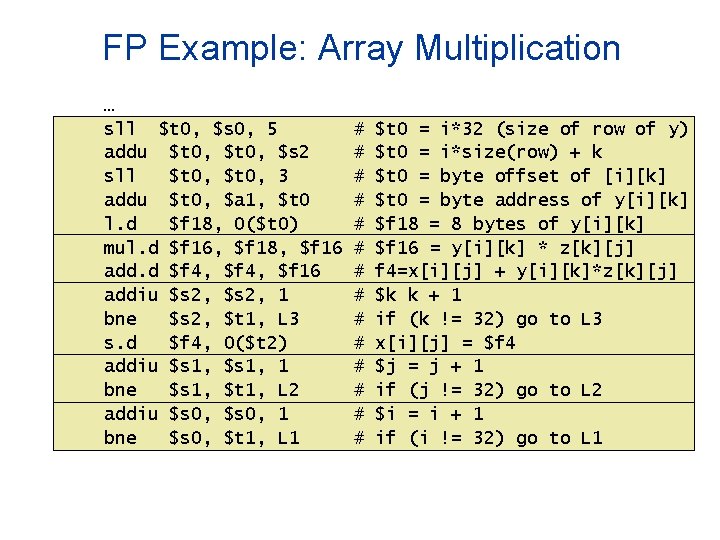

FP Example: Array Multiplication … sll $t 0, $s 0, 5 addu $t 0, $s 2 sll $t 0, 3 addu $t 0, $a 1, $t 0 l. d $f 18, 0($t 0) mul. d $f 16, $f 18, $f 16 add. d $f 4, $f 16 addiu $s 2, 1 bne $s 2, $t 1, L 3 s. d $f 4, 0($t 2) addiu $s 1, 1 bne $s 1, $t 1, L 2 addiu $s 0, 1 bne $s 0, $t 1, L 1 # # # # $t 0 = i*32 (size of row of y) $t 0 = i*size(row) + k $t 0 = byte offset of [i][k] $t 0 = byte address of y[i][k] $f 18 = 8 bytes of y[i][k] $f 16 = y[i][k] * z[k][j] f 4=x[i][j] + y[i][k]*z[k][j] $k k + 1 if (k != 32) go to L 3 x[i][j] = $f 4 $j = j + 1 if (j != 32) go to L 2 $i = i + 1 if (i != 32) go to L 1

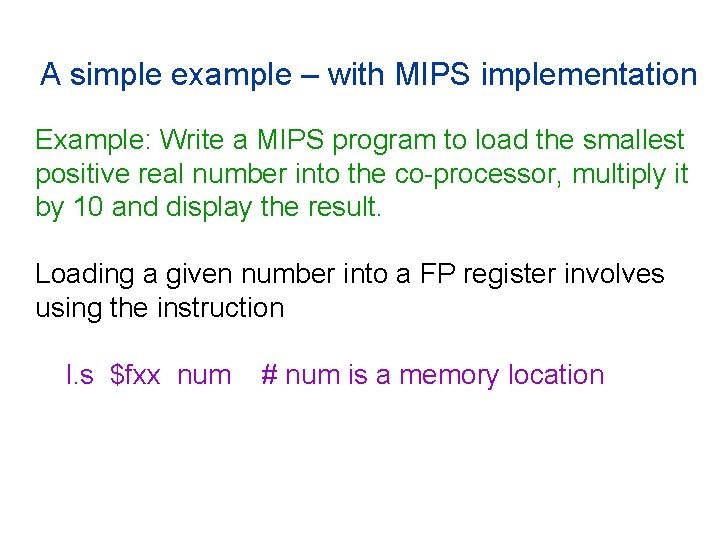

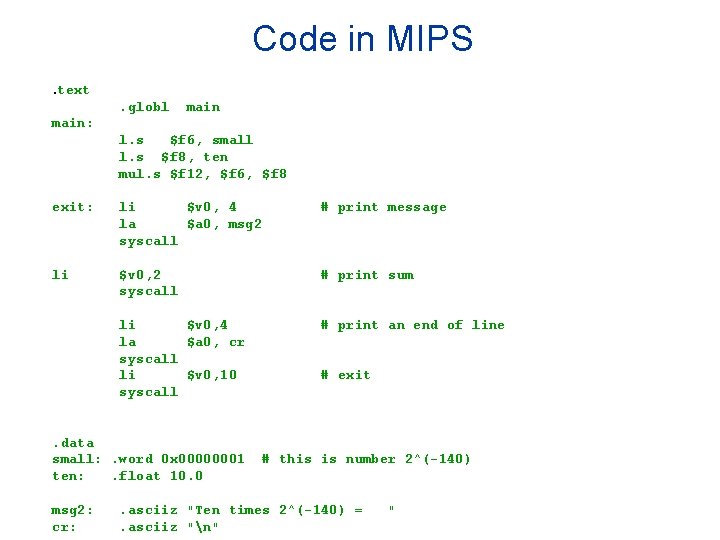

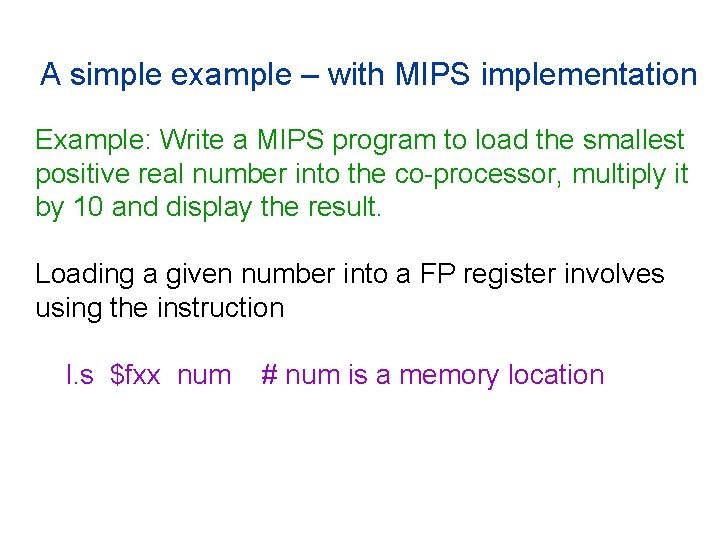

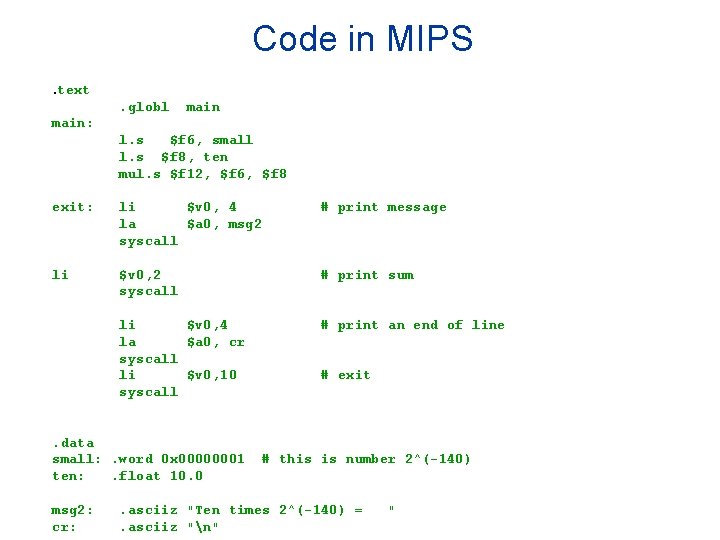

A simple example – with MIPS implementation Example: Write a MIPS program to load the smallest positive real number into the co-processor, multiply it by 10 and display the result. Loading a given number into a FP register involves using the instruction l. s $fxx num # num is a memory location

Code in MIPS. text. globl main: l. s $f 6, small l. s $f 8, ten mul. s $f 12, $f 6, $f 8 exit: li $v 0, 4 la $a 0, msg 2 syscall # print message li $v 0, 2 syscall # print sum li $v 0, 4 la $a 0, cr syscall li $v 0, 10 syscall # print an end of line . data small: . word 0 x 00000001 ten: . float 10. 0 msg 2: cr: # exit # this is number 2^(-140) . asciiz "Ten times 2^(-140) =. asciiz "n" "

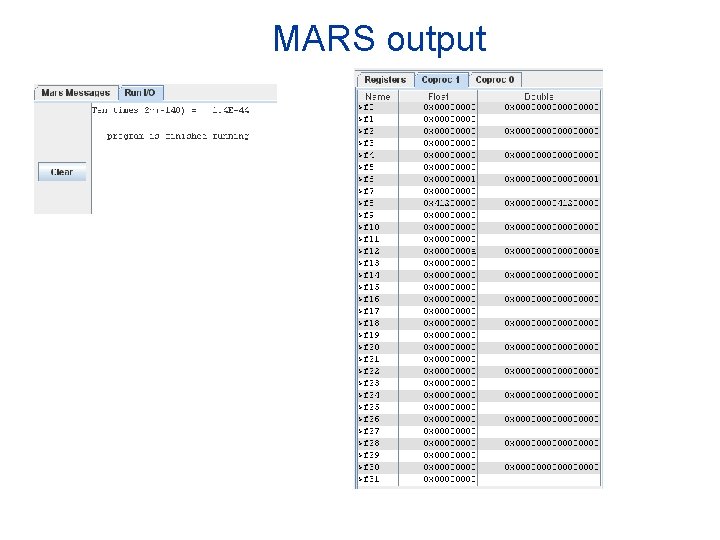

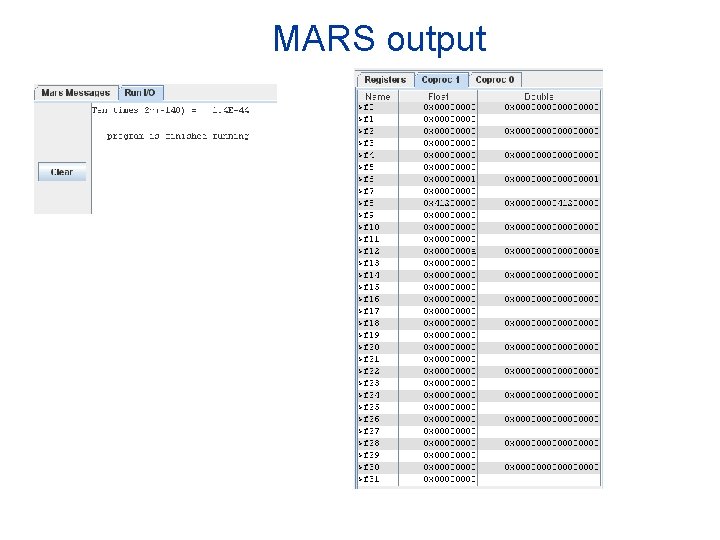

MARS output

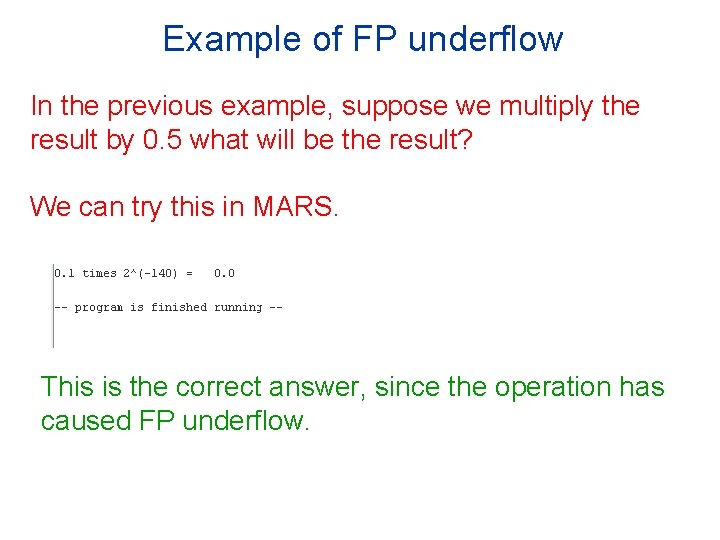

Example of FP underflow In the previous example, suppose we multiply the result by 0. 5 what will be the result? We can try this in MARS. This is the correct answer, since the operation has caused FP underflow.

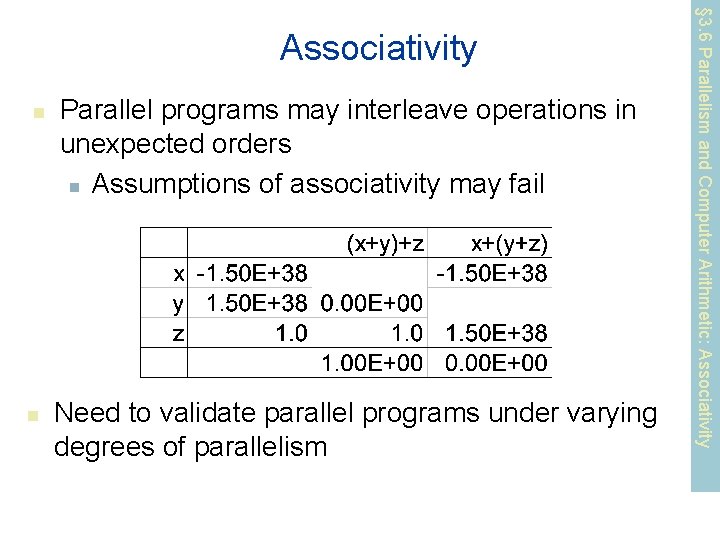

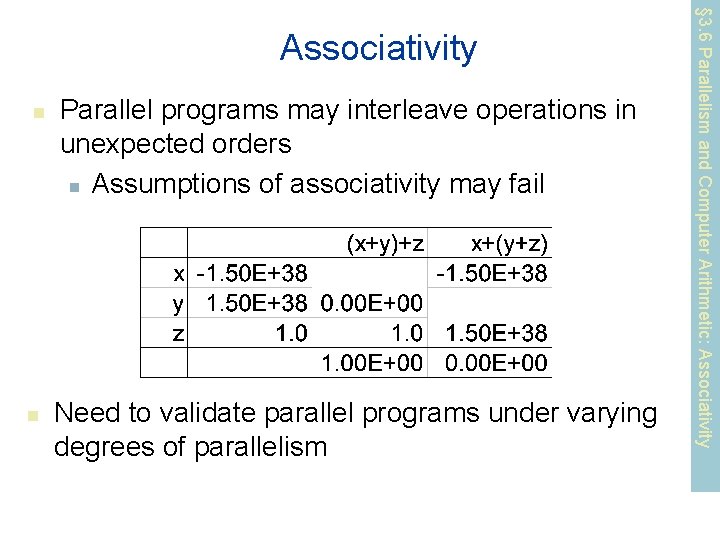

n n Parallel programs may interleave operations in unexpected orders n Assumptions of associativity may fail Need to validate parallel programs under varying degrees of parallelism § 3. 6 Parallelism and Computer Arithmetic: Associativity

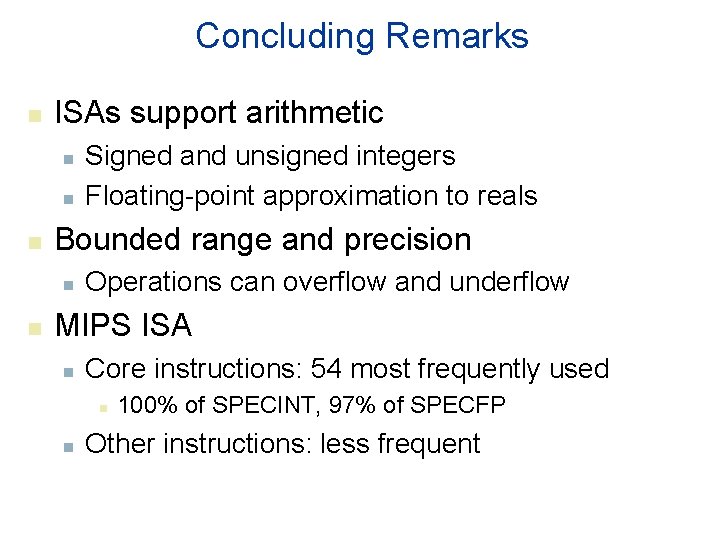

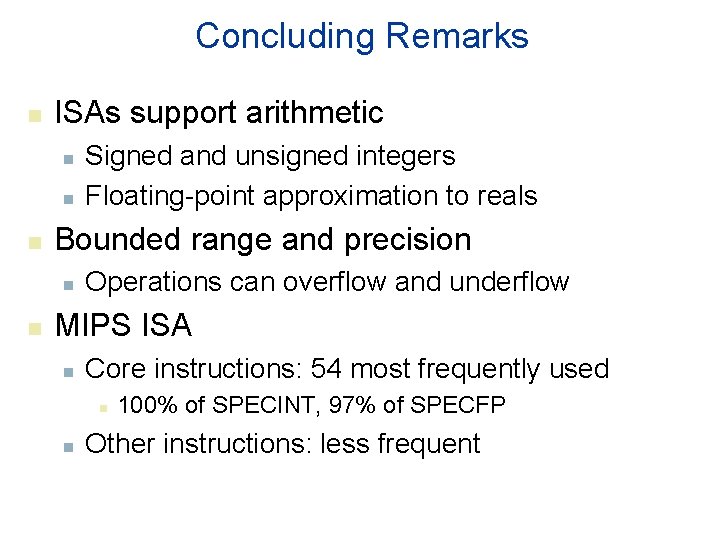

Concluding Remarks n ISAs support arithmetic n n n Bounded range and precision n n Signed and unsigned integers Floating-point approximation to reals Operations can overflow and underflow MIPS ISA n Core instructions: 54 most frequently used n n 100% of SPECINT, 97% of SPECFP Other instructions: less frequent