Lecture 1 What is historiography and why is

- Slides: 29

Lecture 1 What is historiography and why is it important?

What we’ll do • Analyse pioneers of historical approaches – What have historians seen as important to study? – How have they gone about studying it? – What are the benefits and costs of the approach?

Two meanings of ‘historiography’

First meaning of historiography • It can describe the body of work written on a specific topic. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians have studied that topic using particular sources, techniques, and theoretical approaches. Scholars discuss historiography topically – such as the History of the Weimar Republic or the British Empire or the French Revolution’ -- or the History of Fashion – as well as different approaches and genres, such as political, social or cultural history.

Second meaning Historiography = History of history 2 ( H )

Second meaning… How historians have approached their craft

Second meaning • Refers to both the study of the methodology of historians and the development of history as a discipline. The research interests of historians change over time. In recent decades there has been a shift away from traditional diplomatic, economic and political history toward newer approaches, especially social and cultural studies. Reflections on methodologies are guided by ‘Philosophies of History’.

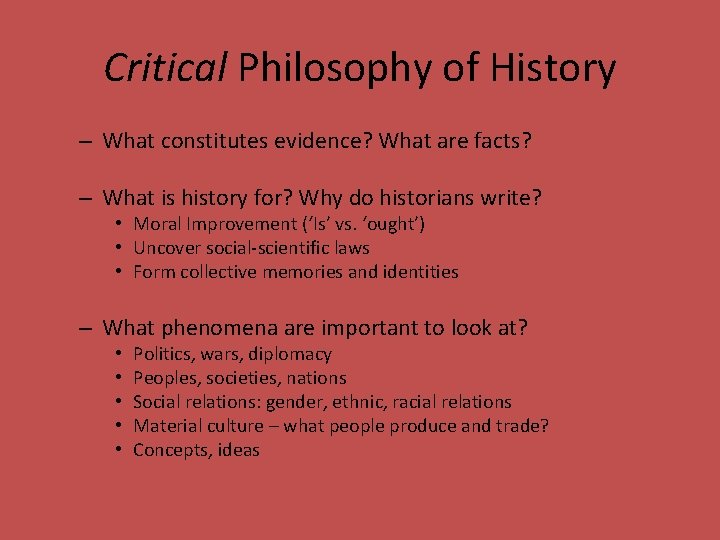

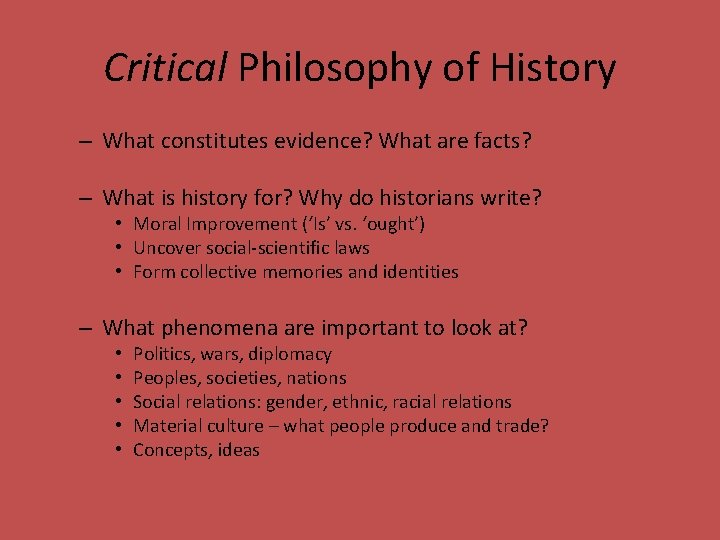

Critical Philosophy of History – What constitutes evidence? What are facts? – What is history for? Why do historians write? • Moral Improvement (‘Is’ vs. ‘ought’) • Uncover social-scientific laws • Form collective memories and identities – What phenomena are important to look at? • • • Politics, wars, diplomacy Peoples, societies, nations Social relations: gender, ethnic, racial relations Material culture – what people produce and trade? Concepts, ideas

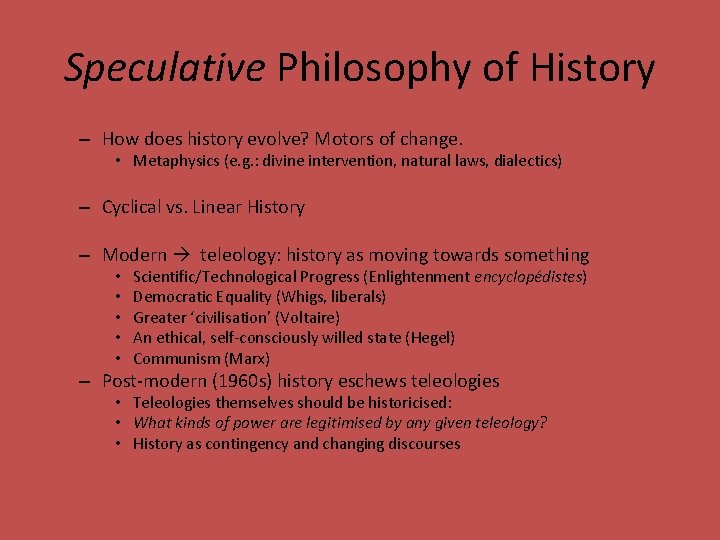

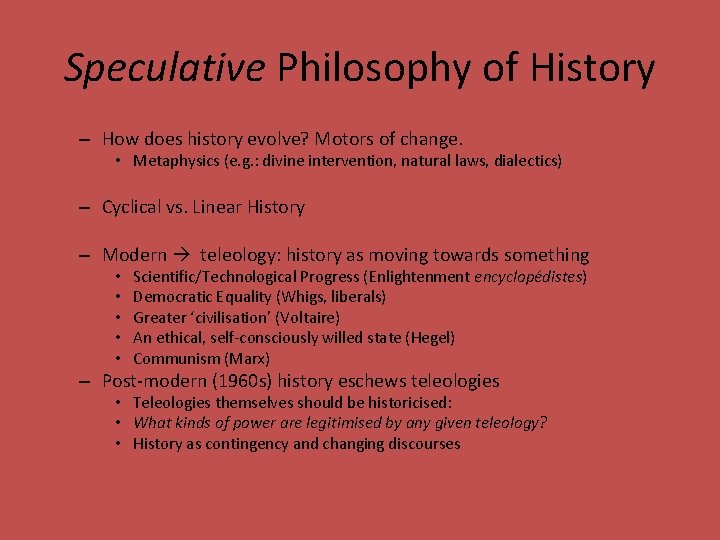

Speculative Philosophy of History – How does history evolve? Motors of change. • Metaphysics (e. g. : divine intervention, natural laws, dialectics) – Cyclical vs. Linear History – Modern teleology: history as moving towards something • • • Scientific/Technological Progress (Enlightenment encyclopédistes) Democratic Equality (Whigs, liberals) Greater ‘civilisation’ (Voltaire) An ethical, self-consciously willed state (Hegel) Communism (Marx) – Post-modern (1960 s) history eschews teleologies • Teleologies themselves should be historicised: • What kinds of power are legitimised by any given teleology? • History as contingency and changing discourses

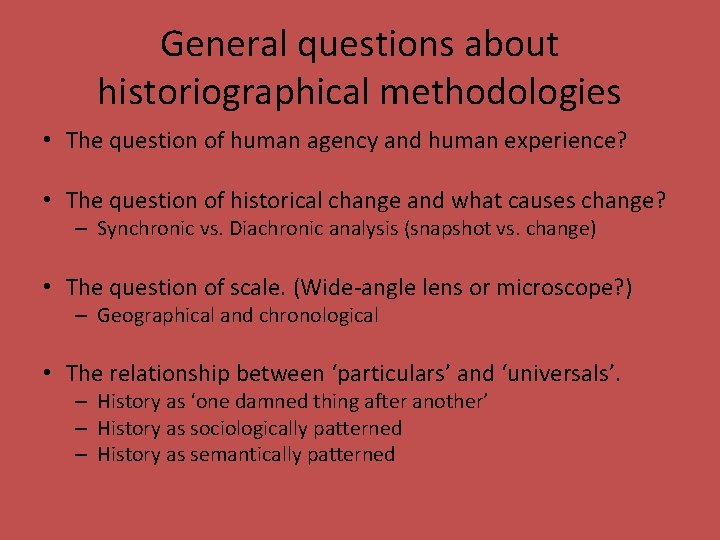

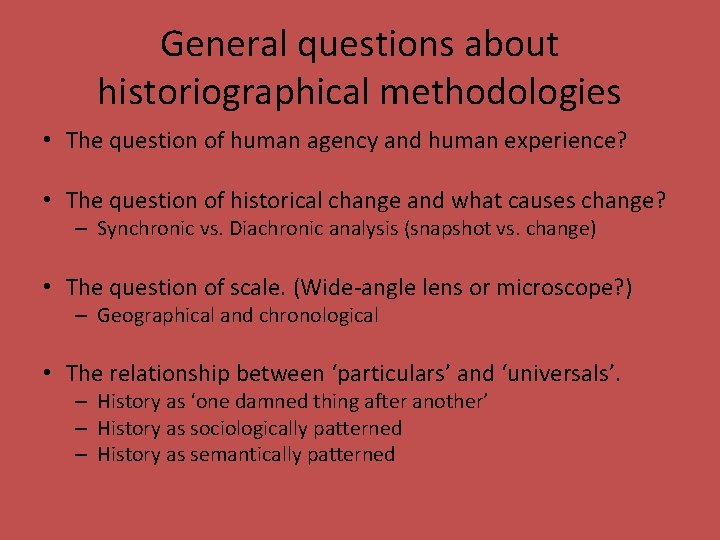

General questions about historiographical methodologies • The question of human agency and human experience? • The question of historical change and what causes change? – Synchronic vs. Diachronic analysis (snapshot vs. change) • The question of scale. (Wide-angle lens or microscope? ) – Geographical and chronological • The relationship between ‘particulars’ and ‘universals’. – History as ‘one damned thing after another’ – History as sociologically patterned – History as semantically patterned

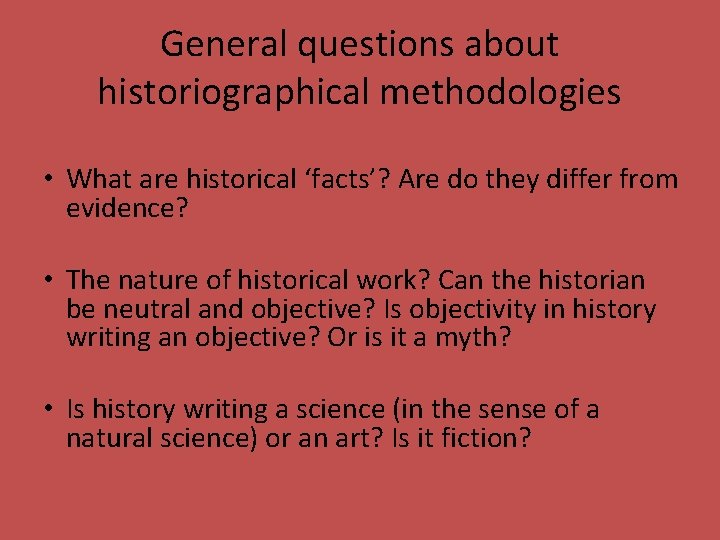

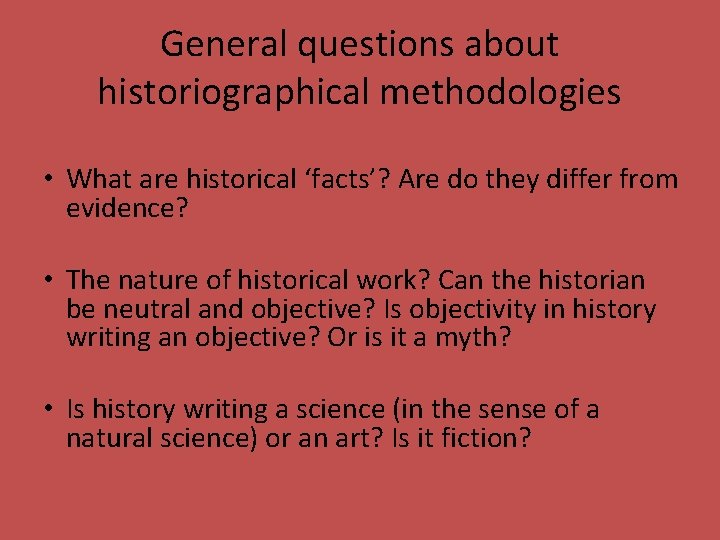

General questions about historiographical methodologies • What are historical ‘facts’? Are do they differ from evidence? • The nature of historical work? Can the historian be neutral and objective? Is objectivity in history writing an objective? Or is it a myth? • Is history writing a science (in the sense of a natural science) or an art? Is it fiction?

How to prepare for this module • Listen to the lecture • Read the textbook (Companion to Western Historical Thought) • Read primary sources–ask above questions • Read background texts–what are the debates

Reading primary sources • What do historians consider worthy of their attention? • Why? – Philosophical commitments – Assumptions, biases, their own historical contexts • What are the implications of their interpretations, at the time they wrote and after? – What were they writing against? – Debates and legacies

Assessments • Two formative pieces – Extrapolate from the many on the module website – Ask your own questions! • Three hour exam – pre-circulated questions – Gobbets (not pre-circulated) – Essay Question (pre-circulated) – Historiography and YOU: your views (undecided… stay tuned – but example: what is your favorite methodological approach? What do you see as the value of history? )

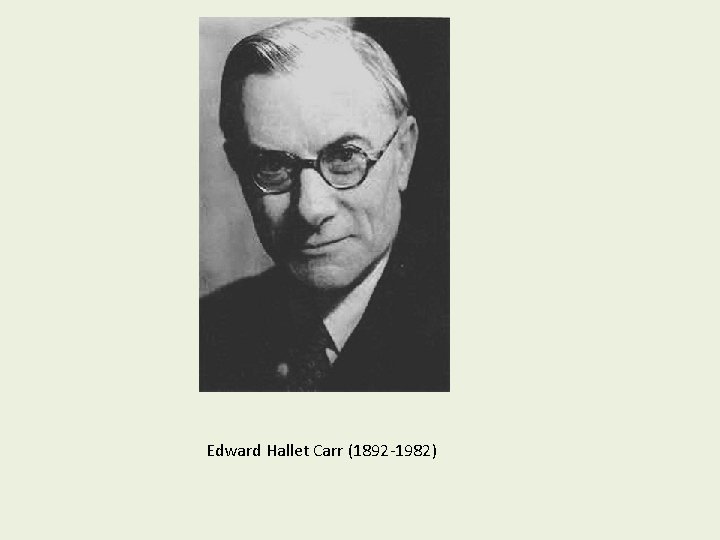

Edward Hallet Carr (1892 -1982)

E. H. Carr • Diplomat, 1916 -1936 • Professor of International Relations • WWII – diplomat again • Wrote about Soviet Union and Russian Revolution

E. H. Carr • Believed in progress, socialism; anti-liberal • Enthusiastic about USSR / UK social welfare state • Opposed to moralism • Historical assessments: reactionary or progressive • History as social science – Hypothesis before empirical research – Generalizable claims

Ways of doing history at the time (1950 s 60 s) Fact fetching. Historical truth simply emerges from the archives. Positivism: fr. ‘positif’: in its philosophical sense it means 'imposed on the mind by experience’ August Comte (1798 -1857) Knowledge derived from mathematical formula and sensory experience is the exclusive sources of all authoritative knowledge. Therefore valid knowledge can only be found in the knowledge produced by the natural sciences and mathematics.

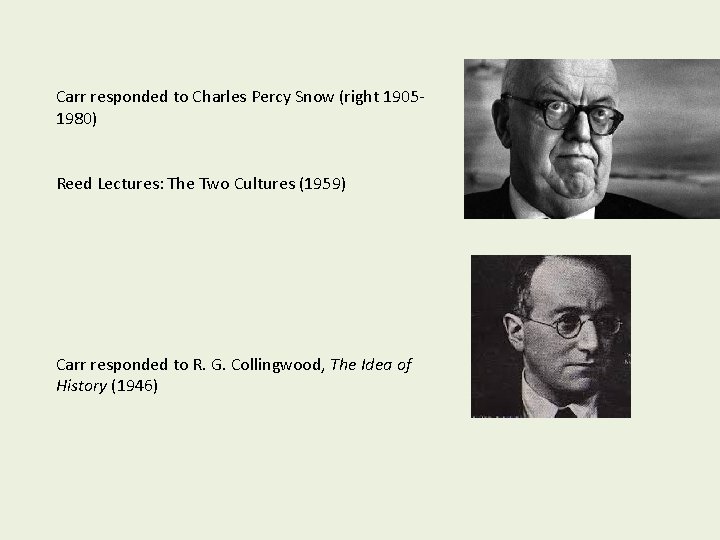

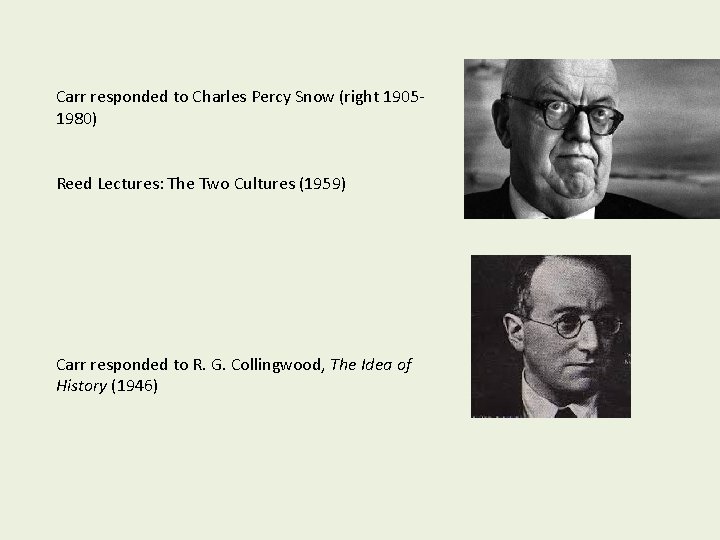

Carr responded to Charles Percy Snow (right 19051980) Reed Lectures: The Two Cultures (1959) Carr responded to R. G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (1946)

‘between …. of an untenable theory of history as an objective compilation of facts, of the unqualified primacy of fact over interpretation, and …. of an equally untenable theory of history as the subjective product of the mind of the historian who establishes the facts of history and masters them through the processes of interpretation, between a view of history having the centre of gravity in the past and a view having the centre of gravity in the present (What is History? , p. 29)

Carr’s ‘Snow/Collingwood’ compromise • ‘Scientists, social scientists and historians are all engaged in the same study: The study of man and his environment, of the effects of man on his environment and of his environment on man. The object of the study is the same: to increase man’s understanding of, and mastery over, his environment…. . The presuppositions and the methods of the physicist, the geologist, the psychologist and the historian differ widely in detail…. But historians and physical scientists are united in the fundamental purpose of seeking to explain, and in the fundamental procedure of question and answer. ’ (Carr, What is History? p. 80)

WHAT IS A FACT? ‘The facts speak only when the historian calls on them: it is he who decides to which facts to give the floor, and in what order or context…. It is the historian who has decided for his own reason that Cesar’s crossing of that petty stream, the Rubicon, is a fact of history, whereas the crossing of the Rubicon by millions of other people…interest nobody at all. ’ (What is History? 11)

‘Before you study the historian, study historical and social environment. The historian, being an individual, is also a product of history and of society: and it is in this twofold light that the student of history has to learn to regard him. ’ (What is History? p. 38)

David Lowenthal The Past is a Foreign Country (1985)

David Lowenthal • Memory vs. history – Attitudes towards knowledge • History as consensual • History as collective memory • Past as difference (risks to this? ) • History as liberating (how past impinges on present)

Preservation has deepened our knowledge of the past but dampened creative use of it. Specialists learn more than ever about our central biblical and classical traditions, but most people now lack an informed appreciation of them. Our precursors identified with a unitary antiquity whose fragmented vestiges became models for their own creations. Our own numerous exotic pasts, prized as vestiges, are divested of the iconographic meanings they once embodied. It is no longer the presence of the past that speaks to us, but its past-ness. Now a foreign country with a booming tourist trade, the past has undergone the usual consequences of popularity. The more it is appreciated for its own sake, the less real or relevant it becomes. No longer revered or feared, the past is swallowed up by an ever expanding present; we enlarge our sense of the contemporary at the expense of realizing its connection with the past. ‘We are flooded with disposable memoranda from us to ourselves’…. but ‘we tragically inept at receiving message from our ancestors’. (p. xvii)

However, faithfully we preserve, however authentically, we restore, however deeply we immerse ourselves in bygone times, life back then was based on way of being and believing incommensurable with our own. The past’s difference is one of its charms: no one would yearn for it if it merely replicated the present. But we cannot help but view and celebrate it through present-day lenses. ’ (Lowenthal, p. XVI)

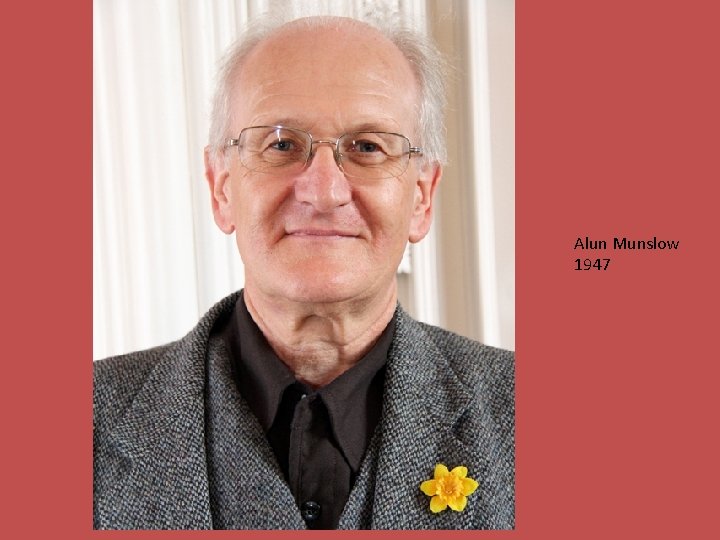

Alun Munslow 1947

Munslow • Deconstruction of History (1997) • Focus on narratives as ideological commitments. History as entangled in the present… • Impact of post-modernism on history – Re-presentations, adapted to the here-and-now – History as literature. – Claims about history as a science have little purchase