Learningand Remembering What can students do to increase

Learning…and Remembering

What can students do to increase the likelihood of learning and REMEMBERING important academic information? Source: Richardson and Morgan. Reading to Learn in the Content Areas, 2003.

Compare the functioning of the brain to how a computer works.

A computer saves information… …the brain remembers information. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

A computer allows typed information to be saved and ready for retrieval…the brain allows you to access knowledge you “wrote” to your memory earlier. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

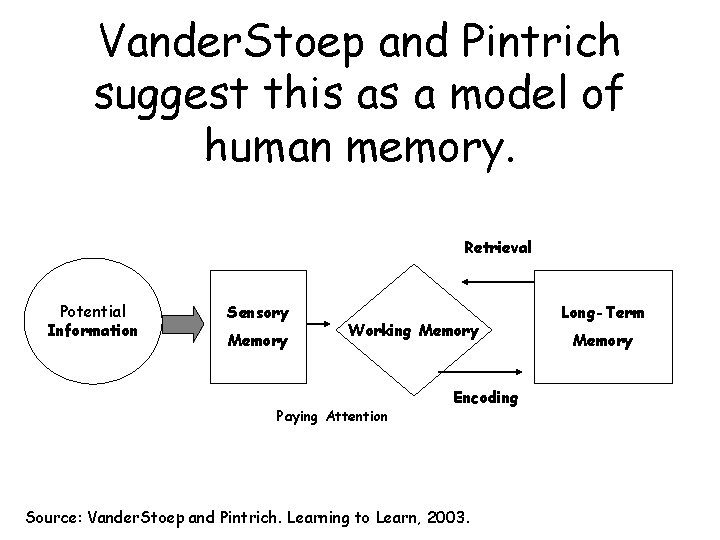

Vander. Stoep and Pintrich suggest this as a model of human memory. Retrieval Potential Information Sensory Memory Working Memory Paying Attention Encoding Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003. Long-Term Memory

We learn in three specific steps: Step 1: Information is presented and we pay attention to what we want to learn. Anytime you are awake and conscious, you are taking material from the outside world and making sense of it or processing it. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

If you constantly pay attention to all events in your environment, you will likely not get anything accomplished. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

With all of the stimuli in our environment, how do we manage to concentrate on anything? We attend to some stimuli and block others out. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Vander. Stoep and Pintrich say that paying attention to anything has a “cost”involved— we only have so much “attention money” to spend. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Once the attention money is spent, we cannot pay attention anymore… we have to carefully choose what we will “buy” with our attention money. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Paying attention involves making choices! Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

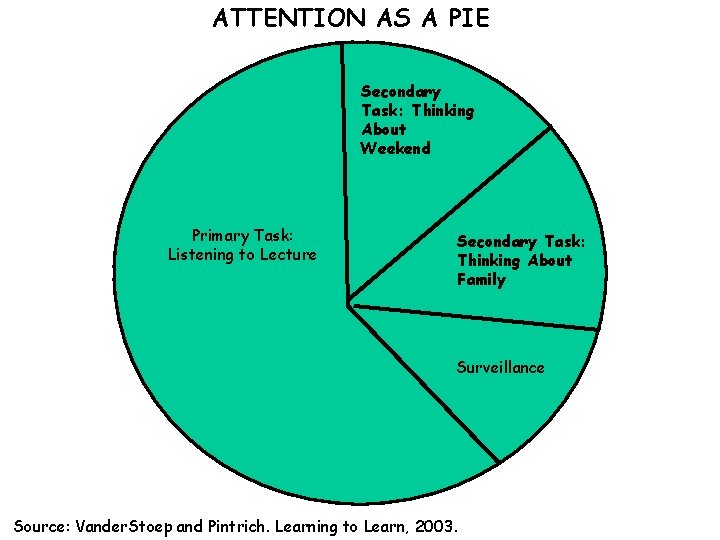

Our goal is to pay attention to the important stimuli and “block out” the unimportant stimuli because attention is like a pie… it is limited in size and can be cut into several pieces. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

When we spend our attention resources on one thing, it reduces our ability to attend to others. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Attention is divided into primary, secondary, and surveillance tasks. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Primary tasks are the main focus to which you devote most of your attention. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Secondary tasks are often other activities or thoughts that demand your attention.

In addition, we are constantly aware of our surroundings from background noise to our skin touching the rough cover of the chair upon which we sitthis is called surveillance attention. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

When you are studying, reading, or listening to lectures, the more you reduce distractions of other events vying for your attention… Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

… the more attention you can devote to your primary task. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

ATTENTION AS A PIE Secondary Task: Thinking About Weekend Primary Task: Listening to Lecture Secondary Task: Thinking About Family Surveillance Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Let’s try an experiment. 1. Get paper, pencil, and a partner. 2. Pick a song to which you know almost all of the lyrics. 3. Have a friend time you and record the number of words you write down in the first minute and compare it to the number of words you write in the second minute. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

TASK: For one minute, write down the words to the song you chose. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

TASK: Second Minute Continue to write down the words to this song, but now, simultaneously, start saying (out loud) the Pledge of Allegiance or some other speech, creed, poem, or story that you know well. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

What happened when you tried to divide your attention pie? Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Attending to multiple stimuli, reduces the ability to process information. What implications does this information have for students who study in front of a television or listen to music with lyrics? Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

In improving attention, you should strive for automatization—making certain cognitive tasks automatic. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

This is important—when a task is automatic—you don’t have to devote as much attention to it… …or spend your attention money on it. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

When you are learning calculus, it helps to have automatized algebra. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Most of us have automatized these tasks: 1. Decoding words. 2. Understanding meaning of individual words. 3. Understanding what sentences mean. 4. Understanding main themes/ideas. 5. Identifying how reading relates to other courses. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

This automatization makes learning higher level reading tasks easier… Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

…we have to pay less attention to the basic functions of reading and can devote our attention to learning higher level information. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

How do we automatize such tasks as reading? Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

How do we improve attention? ? ? PRACTICE The more you study the better you will become at it-IF YOU DO IT RIGHT. Practice makes permanent—be sure what you practice is what you want to learn and do. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Reduce competition from secondary tasks. Don’t bring problems/outside activities with you to the study table. Address them before you try to study. Hungry? Get something to eat. Need to apologize to a friend—do it! Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Don’t listen to music. If you use music to drown the noise around you, you need to study somewhere quieter. Attention demanding activities do not need to compete with background noise that can be eliminated. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Find a good study environment. The general rule is the quieter the better. Set aside definite periods of time to be a student. Your full-time job is to be the best student you can be. Invest some thought and find a good, quiet place to study. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Take breaks when your attention wanders. Good break activities vary. Brisk walks and short naps work well. DON’T watch TV for a long time, eat snacks with high sugar, or make long phone calls. Promise yourself a 15 -minute break if you do quality work for 45 minutes. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Stay rested and healthy. Illness is physically draining. You can’t control when you get sick, but you can control how much rest you get. The rested person is the best learner. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

We learn in three specific steps: Step 2: Information is now brought into memory so the mind can use it later. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

How? Through: Sensory memory Working memory Long-term memory Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

What is sensory memory? Sensory memory stores information from the outside world for a very brief period of time. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

How long does sensory memory hold information? Visual images— less than a second Auditory information for two to three second. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Try the experiment in Learning to Learn on page 91 to illustrate how briefly information stays in sensory memory. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

What happens to the information that doesn’t get into sensory memory? For all intents and purposes, it is lost forever…. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

If the information does get into long-term memory it in on the road to learning---it is now in working memory. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Working memory has two important features: 1. It stores only a limited amount of information; it has limited capacity. 2. It stores this limited information for only a limited period of time; it has limited duration. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

If you don’t transfer the information to long-term memory, you will forget it. Information that is chunked—combining separate pieces of information into units that can be remembered as one meaningful piece— helps students to lodge information in longterm memory. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Try the Short-term Memory experiment on page 92 -93 of Learning to Learn to see how chunking works. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Long-term Memory is the mind’s permanent warehouse. In theory, long-term memory can hold an infinite amount of information and can hold it for your lifetime. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

What kinds of knowledge are stored in long-term memory? • Declarative -facts, names, and other general knowledge learned and remembered throughout life • Procedural -motor skills, behaviors, and task that involve activities and procedures • Conditional -the knowledge of when to activate certain parts of your long-term memory Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Declarative knowledge is WHAT you have learned in terms of facts and general knowledge. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Procedural knowledge is the memory of HOW to study or form “programs. ” Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Most importantly, conditional knowledge activates certain parts of long-term memory to tell us WHEN to use different learning strategies. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Information lodges in long-term memory through the process of encoding. Encoding can either be through shallow or deep processing. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Shallow processing occurs when you are paying minimal attention to what you are learning. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Deep processing is an umbrella term to refer to a variety of highlevel cognitive strategies to lead to a sophisticated understanding of material. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Try Exercise 5. 5 in Learning to Learn on page 95 to experience the difference between shallow and deep processing. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Deep processing is even more helpful when the material you are learning is more complex than a simple word list. College texts are complex; they have concepts with multiple ideas that are often interrelated. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Deep processing takes more time and effort which requires more effort and commitment on your part. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

The time you spend in deep processing is an investment. Study right, study hard, and you will thoroughly understand the material. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

We learn in three specific steps: Step 3: Remembering: Getting information out. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

People remember in two ways: 1. Recognition memory-identifying the thing you are trying to remember when you are given a set of possibilities. 2. Recall memory-generating a portion of your memory on your own, without a list of alternatives. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

What does this information suggest in terms of studying for tests? A self-regulated learner recognizes that different school tasks require different types of learning. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

How does it work in test preparation? • Multiple-choice tests on a purely recognition level are easier to study for—the task is one of choosing from a set of finite options. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Essay tests will require deep processing over time because answers are generated from a body of learning---there are no lists from which to choose. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Vander. Stoep and Pintrich recommend four general principles to improve your memory. Chunk Put pieces of information into meaningful units. Don’t treat related material as separate pieces—look for connections and associations. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Use deep processing Encode information at a deep level, not a shallow one. Don’t settle for memorization. Push yourself to understand information at a higher cognitive level. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Use prior knowledge. If you are having trouble remembering something, put it in terms you can understand know a lot about. The more you know; the easier it is to learn and remember. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

Use cues. Use as many cues as you can from the context of what you have studies to help you remember it. Think of related material and other information that will trigger your memory. For example: Where were you when you learned this? What part of the text explained this information. Source: Vander. Stoep and Pintrich. Learning to Learn, 2003.

…and that’s how learning and remembering works!

- Slides: 71