LANGUAGE VARIATION LANGUAGE AND REGIONAL VARIATION Language versus

- Slides: 29

LANGUAGE VARIATION

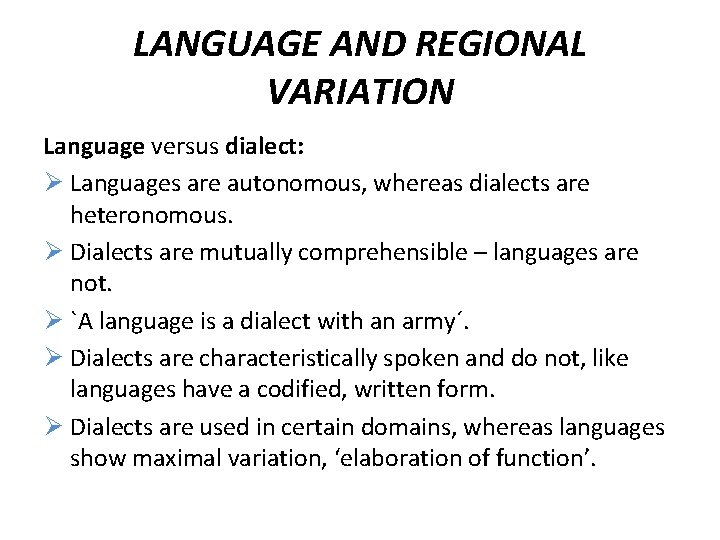

LANGUAGE AND REGIONAL VARIATION Language versus dialect: Ø Languages are autonomous, whereas dialects are heteronomous. Ø Dialects are mutually comprehensible – languages are not. Ø `A language is a dialect with an army´. Ø Dialects are characteristically spoken and do not, like languages have a codified, written form. Ø Dialects are used in certain domains, whereas languages show maximal variation, ‘elaboration of function’.

Accent versus dialect. Pronunciation vs syntax and vocabulary. Who speaks with an accent? Standard English is seen as a “common core”; Mid-Atlantic, Euro-English, International English.

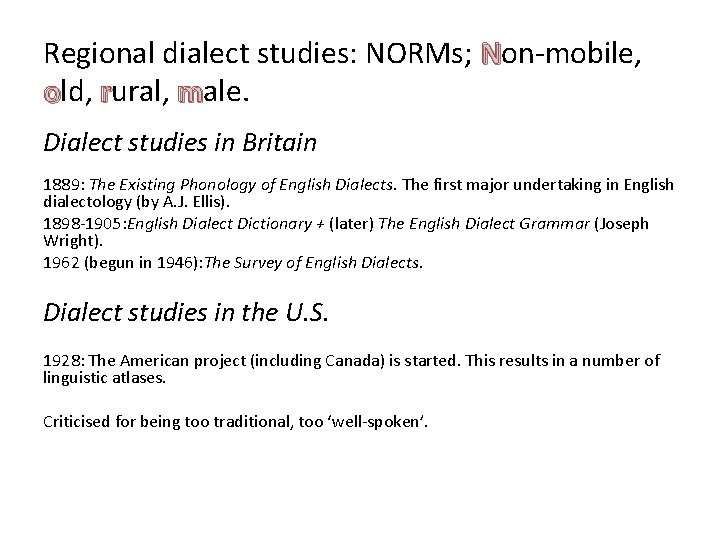

Regional dialect studies: NORMs; Non-mobile, old, rural, male. Dialect studies in Britain 1889: The Existing Phonology of English Dialects. The first major undertaking in English dialectology (by A. J. Ellis). 1898 -1905: English Dialect Dictionary + (later) The English Dialect Grammar (Joseph Wright). 1962 (begun in 1946): The Survey of English Dialects. Dialect studies in the U. S. 1928: The American project (including Canada) is started. This results in a number of linguistic atlases. Criticised for being too traditional, too ‘well-spoken’.

1985: DARE (Dictionary of American Regional English). “The America of DARE’s questionnaire is a land of small towns and villages where farmers still plow with mules or horses, with few factory workers, no unions and bosses, no prostitutes (and not much sex of any sort). The work should have been called Dictionary of English Spoken by Oldfashioned, Elderly American Hicks. ” English Today, 1987

: a boundary line drawn between areas which use different linguistic items. isoglosses coincide. : where a number of : where dialects/language merge into one another, cf. the Nordic countries. : two very different language varieties co-exist with distinct functions (high / low varieties), cf. the Early Middle English period: Anglo-Norman and English.

Language Planning (important in newly independent countries): ü selection ü codification ü elaboration ü implementation ü acceptance

Pidgins: Pidgins trade languages, usually with no native speakers Creoles: Creoles a pidgin which has developed into a full language. It has acquired native speakers and consequently also developed in complexity and use. Cameroon (Africa) Gif di book fo mi. ‘Give the book to me’

Tok Pisin (Papua New Guinea; So. Pacific) Mi driman long kilim wanpela snek. I dream about kill-him one-fellow snake ‘I dream of killing a snake’

LANGUAGE AND SOCIAL VARIATION

Sociolinguistics has connections with sociology, anthropology, and social psychology. Regional varieties are created by geographical barriers - social varieties by barriers caused by social class, ethnicity and gender and age. Ethnic varieties in New York: Jews, Italians, Afro. American English speakers (AAVE), Anglo. Saxons, Hispanics. All varieties are governed by their own rules. Vernaculars = social dialects

William Labov – the pioneer in sociolinguistics (in the 1960 s) q. Sociolinguistic variables: qstore: I Saks (upper middle class) II Macy’s (middle class) III Kleins (working class) qsex of the informant qage of the informant qoccupation of the informant

Linguistic variable. q. Postvocalic /r/, car park

Language and age: Lexical items (slang). The importance of peer group influence. Changes in real time (=changes that last), and changes in apparent time (= a ‘change’ that doesn’t last). Language and gender: Gender varieties: things said about men and women differ, but also what is said by them. Women’s speech is reported to be more ‘correct’ than that of men since they use more ‘status forms’. Is the use of swear words and four-letter words more accepted in men?

Language & gender: a brief summary v. In all styles, women tend to use fewer forms that are associated with low prestige than men. v. In formal contexts, women seem to be more sensitive to prestige forms than men. v. Lower middle-class women change their speech more than men in formal situations. In the least formal style, they use a high proportion of the low-prestige variant but in formal styles, they correct their speech to correspond to that of the social class above them.

v. Use of non-standard forms seems to be associated not only with working-class speakers, but also with male speakers. v. Women are more sensitive to linguistic norms than men: women believe that they use more high-prestige variants than they do, whereas men believe they use fewer high-prestige variants than they do.

In conversation women negotiate goals, show speaker accomodation, co-operativeness, consolidate friendship, maintain social relations. In mixed-gender conversation they give more back-channels, receive fewer back-channels, hold the floor less, interrupt much less. Men’s language: competitiveness, exchange of information. In mixed-gender conversation: interrupt more, receive more back channels (minimal responses), give fewer back channels, hold the floor more, interrupt more (96% of all interruptions are by men).

Idiolect: Idiolect individual properties of a speaker Style: language features occasioned by the situation of use, not user (as regional and social varieties) eg. formal – informal. This leads to style-shifting. Jargon: specialised vocabulary or 'ingroup' marking, slang or terminology. Register: language used in a particular situation: ‘professional registers: ’ legal register, sports announcer talk, lecture

LANGUAGE AND CULTURE

Linguistic determinism (the Sapir – Whorf hypothesis): the hypothesis that the structure of a language governs the way in which its speakers view the world. Linguistic relativity: the hypothesis that language influences oor thoughts to some extent. We lexicalize differently in different languages.

Words for winds on the Shetland Islands: laar flan bat guff gouster vaelensi pirr ‘light wind, more diffuse’ ‘sudden squall’ ‘a slight gust of wind’ ‘a strong puff of wind’ ‘a strong, gusty wind’ ‘a strong gale’ ‘light wind in patches’

Words for ‘snow’ in Inuktitut (Eskimo): aput qana piqsirpoq qimuqsuq ‘snow on the ground’ ‘falling snow’ ‘drifting snow’ ‘snow drift’

Semantic fields with different lexicalisation: colour terms, kinship terms Language Universals: features that can be found in all languages. All languages must fulfil the following criteria: ü must be possible for children to learn ü must be easy and efficient for adults to speak ü must embody the ideas that people normally want to convey ü must function as a communication system in a social and cultural setting

Semantic universals: body part terms, animal names, verbs of sensory perception Pronouns: All known languages have terms at least for the speaker (I) and the addressee (you) Phonological universals: All languages have at least 3 vowels. All languages have stops /ptk, bdg/ usually 3.

Why should we look for language universals? vthey tell us what is possible and impossible in language vthey give an insight into how the brain works vthey show us how human communication is organised

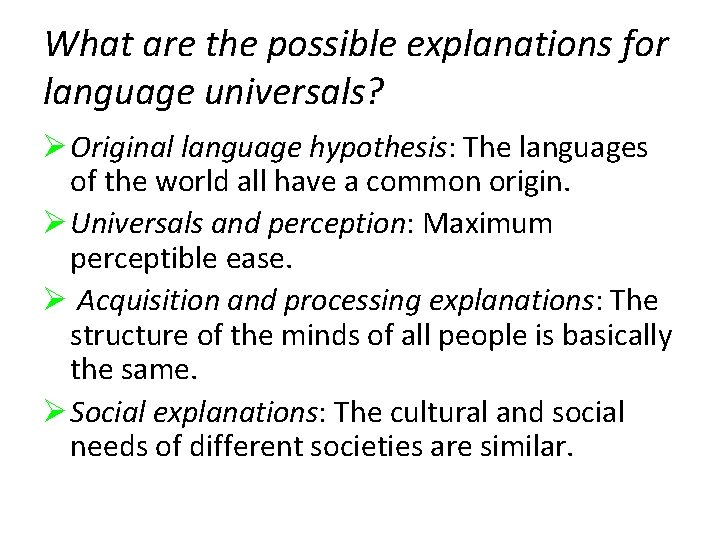

What are the possible explanations for language universals? Ø Original language hypothesis: The languages of the world all have a common origin. Ø Universals and perception: Maximum perceptible ease. Ø Acquisition and processing explanations: The structure of the minds of all people is basically the same. Ø Social explanations: The cultural and social needs of different societies are similar.