Language acquisition II Putting words together The twoword

- Slides: 26

Language acquisition II: Putting words together

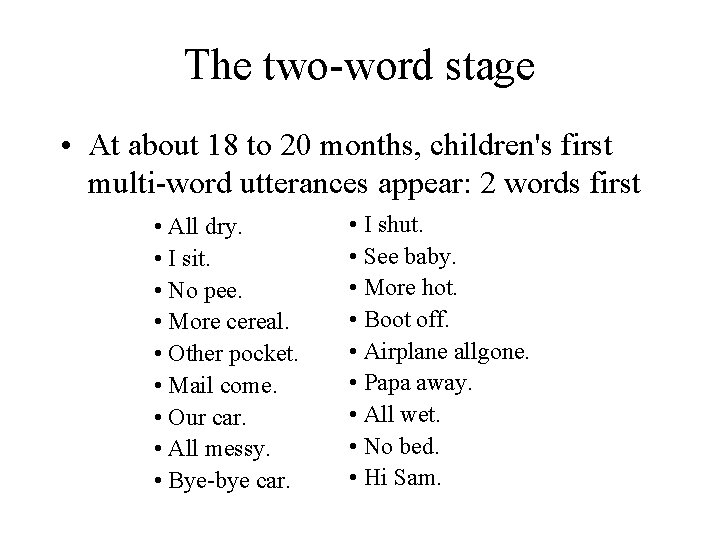

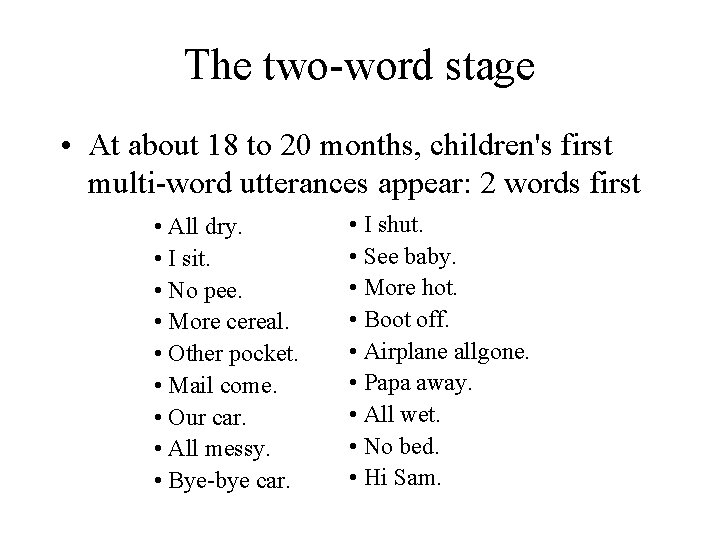

The two-word stage • At about 18 to 20 months, children's first multi-word utterances appear: 2 words first • All dry. • I sit. • No pee. • More cereal. • Other pocket. • Mail come. • Our car. • All messy. • Bye-bye car. • I shut. • See baby. • More hot. • Boot off. • Airplane allgone. • Papa away. • All wet. • No bed. • Hi Sam.

Early Semantics • As with single words, there is much semantic consistency in the two-word stage • Early sentences in cultures around the world tend to focus on a few themes: the appearance, disappearance, and movement of objects; comments about object properties; requests for and rejections of objects or activities; and who/what/where questions

Early Syntax Production • Syntax is already almost perfect! (within the limits of two words) • 95% of sentences produced in this two-word stage have the proper syntactical order • Two-words phrases also have all the components of complex sentences, but not at the same time: – If a child is looking at his mummy fixing a toy on the table which has just been given to her by daddy you might get: subject-verb (Mommy fix), subject-object (Mommy toy), subject-location (Mummy table), verb-location (put table), and so on. • There seems to be no syntactic component that infants can't usethe problem seems to be just that they can't string more than one relation together.

Early Syntax Comprehension • As with single word production, there is a dissociation between comprehension and production • At the two-word stage the infant already can understand very complicated syntax. • How do we know? – Anecdotal evidence: Just hang out with a kid this age! – Experimental evidence: Show two TV screens with different images, and play a sentence describing just one ('Big Bird is tickling Ernie' vs. 'Ernie is tickling Bird'). • The child attends to the screen being described.

From 2 to 3 words • After a two word stage, you might expect a three-word stagebut you'd be wrong. • When a child passes the two-word stag (usually between the age of 2 and 3. 5 years) things get so complicated so fast that no one has yet found a clear sequential pattern for what is happening • It is as if language is suddenly on-line and it just bursts forth • Moreover, some children zoom through the two word stage in just a few months

On the lack of a 3 -word stage • There are well-studied cases, by no means extraordinary, of children apparently having mastered syntax totally by the age of 2 • For example, Roger Brown reported on a child who produced these sentences before her second birthday: – – – I got peanut butter on the paddle. I sit in my high chair yesterday. Fraser, the doll's not in your briefcase. Fix it with the scissor. Sue making more coffee for Fraser. • Clearly, she is not perfect: there a few errors in the sentences…but no one has ever found a single grammatical rule that children at this stage usually get wrong – At the highest estimate, children make errors not more than 8% of the time when an error is makeable, and some estimates range as low as 0. 1%.

A case study: Auxiliary verbs • To get a feel for how amazing this is, let’s consider just one example: the use of auxiliary words- verbs that go with other verbs, – For example ‘can’, ‘should’, ‘must’, ‘be’, and ‘have’ in sentences like “He should have eaten”, “He can be brushing his own teeth now” or “He must have left his mittens in the car”.

A case study: Auxiliary verbs • It has been estimated that there are 24 billion logically-possible orderings of auxiliary words that can legally appear in the same sentence • Of those, only about 100 are actually grammatical in English: we can't say “He have should eaten” or “He be can brushing his teeth now” or “He have must left it” • So ‘chance’ performance is ~ 0%

A case study: Auxiliary verbs • Moreover, the problem is made even more difficult because some misorderings seem like they might be quite plausible by analogy: “He seems happy” “Does he seem happy? ” “He is happy” *“Does he be happy? ” “He did eat” “He didn't eat” “He did a few things” *“He didn’t a few things. ” “I like going” “He likes going” “I can go” *“He cans go” “I am going” *“He bes [ams] going. ”

A case study: Auxiliary verbs • So, the base rate odds of doing it right are minuscule, and the base rate odds of making errors are huge, plus there are many temptations by analogy to do it wrong • One woman studied 66, 000 productions of auxiliary sentences by young infants, in order to examine the pattern of their errors – It turned out to be very easy to do- there were virtually no errors in those sentences!

What do infants do wrong? • The errors that infants do make are limited largely to overgeneralizations of very common rules – They sometimes regularize irregular plurals: “I have two mouses” or “My sister is missing two tooths” – They sometimes regularize irregular verb forms: “I runned back to Mummy” or “ I finded Daddy”. • The only way to get these right is to memorize them, since they are irregular • These errors suggest that children have access to the abstract rules- the child who says ''runned" or "mouses" cannot possibly be repeating it, since s/he will never have heard it: it must be deduced from an implicit understanding of the rule.

Adults do it too • Adults also regularize if the irregular word is infrequent enough: words like ‘trod’ (not ‘treaded’), ‘strove’ (not ‘strived’), ‘dwelt’ (not ‘dwelled’), and ‘smote’ (not ‘smited’) are often regularized • Historical linguists have shown that this certainly does happen, because Old and Middle English have about twice as many irregular verbs (~360) as we do now – The rest have become regularized as the error has become standard. • As a general rule, errors are more likely on less frequent aspects of language, and they are likely to be regularization errors

The problem with passivity • Another example of where low frequency leads English children astray is in comprehending passive sentences, in which the S is not at the beginning of the sentence as it is in most sentences – E. g. ‘The cat was chased by the dog’ is a legal OVS order, rather than the usual SVO • Children have trouble with passive sentences, and often mistake them for SVO sentences, so they will match a cat chasing a the dog to the sentence ‘The cat was chased by the dog. ’

Some other interesting errors • We can get some idea about how children parse language at this stage from their other errors: • "I am heyv" (reponse to 'Behave!") • “Daddy, when you go tinkle you're an eight, and when I go tinkle I'm an eight, right? ” [from ‘urinate’] • In both cases, the child makes a plausible miscalculation about where word boundaries are.

Creoles and pidgins • We can get further insight into what is happening inside children's heads from a very interesting linguistic phenomenon: creolization – A pidgin arises when two peoples who don't speak the same language are suddenly and without advance warning forced to live and work together: their ad hoc communication system is a pidgin – Creolization is the process by which a pidgin language is regularized • Creolization offers us unique insight into linguistic construction in real time.

What pidgin? • Pidgins arise depressingly often in this sorrowful world – The best-known cases sprung from the slave trade in America, and from indentured servitude in the South Pacific – They have also arisen in other less horrific situations: there are pidgins between people who occasionally get a chance to barter but have no formal trade, such as Russian and Scandinavian sailors before the fall of the Soviet Union

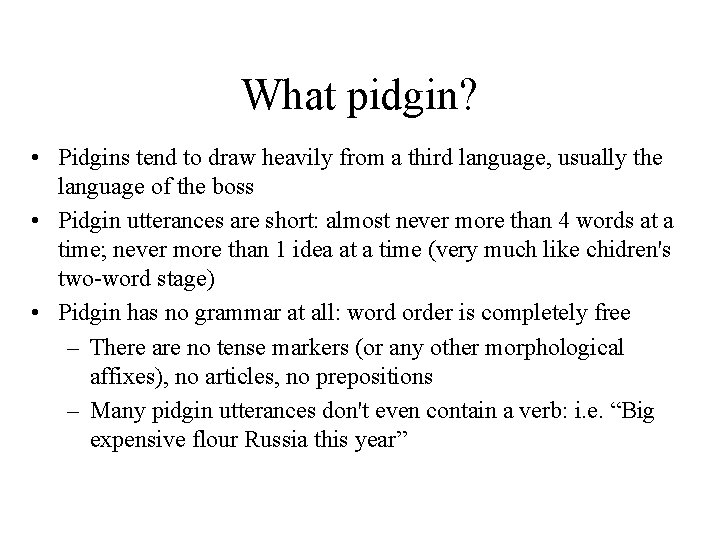

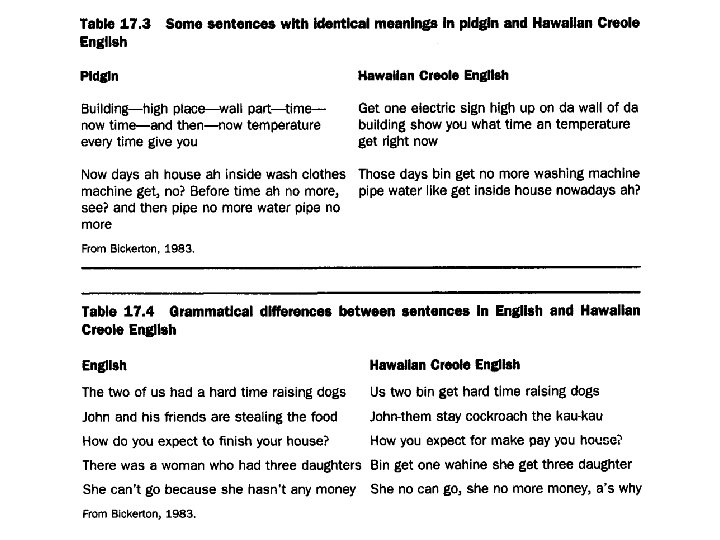

What pidgin? • Pidgins tend to draw heavily from a third language, usually the language of the boss • Pidgin utterances are short: almost never more than 4 words at a time; never more than 1 idea at a time (very much like chidren's two-word stage) • Pidgin has no grammar at all: word order is completely free – There are no tense markers (or any other morphological affixes), no articles, no prepositions – Many pidgin utterances don't even contain a verb: i. e. “Big expensive flour Russia this year”

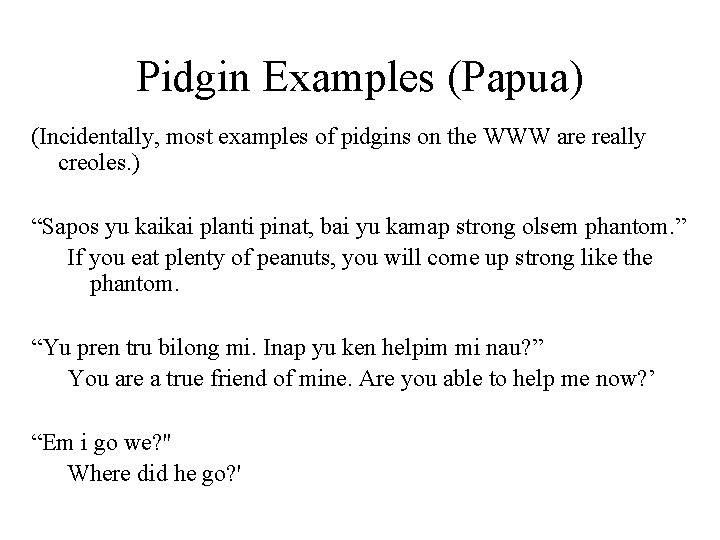

Pidgin Examples (Papua) (Incidentally, most examples of pidgins on the WWW are really creoles. ) “Sapos yu kaikai planti pinat, bai yu kamap strong olsem phantom. ” If you eat plenty of peanuts, you will come up strong like the phantom. “Yu pren tru bilong mi. Inap yu ken helpim mi nau? ” You are a true friend of mine. Are you able to help me now? ’ “Em i go we? " Where did he go? '

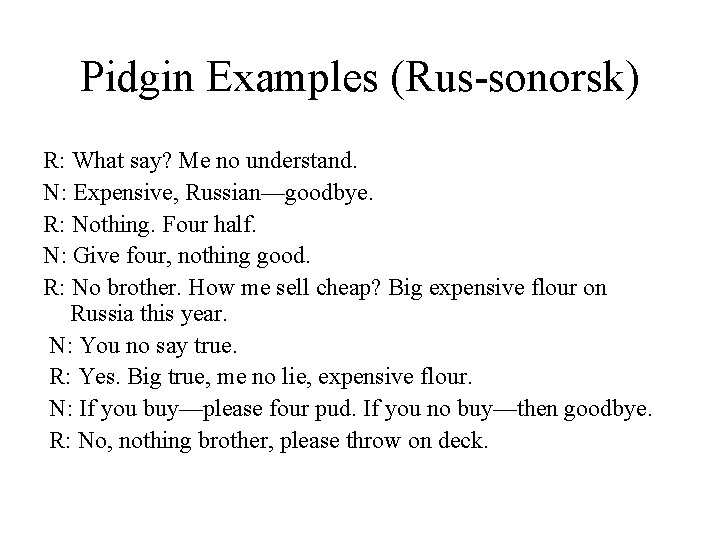

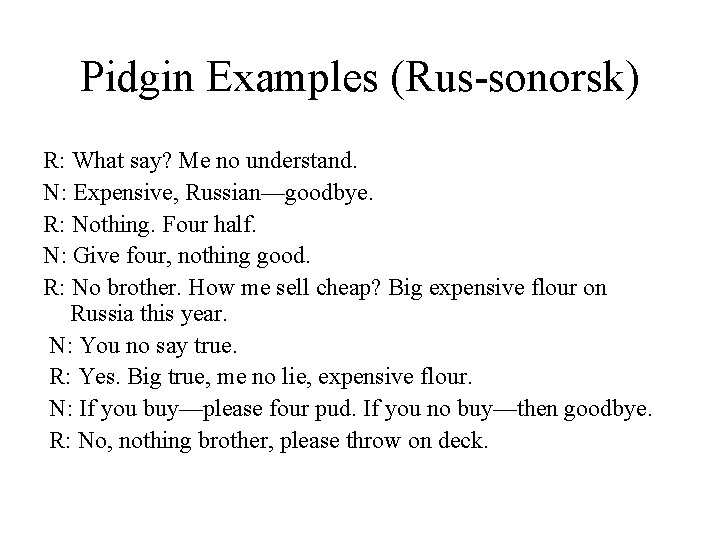

Pidgin Examples (Rus-sonorsk) R: What say? Me no understand. N: Expensive, Russian—goodbye. R: Nothing. Four half. N: Give four, nothing good. R: No brother. How me sell cheap? Big expensive flour on Russia this year. N: You no say true. R: Yes. Big true, me no lie, expensive flour. N: If you buy—please four pud. If you no buy—then goodbye. R: No, nothing brother, please throw on deck.

So care yu pidgin? • Our interest in pidgins in this context is due to the fact that there have been a few cases in which prelinguistic children have been raised in situations in which pidgin was the only language – This happens when they are raised primarily by a caretaker who speaks pidgin • Something remarkable happens in that situation: the language-learning infants regularize the pidgin, add some features, and turn it into creole

What creole? • Unlike pidgins, Creoles include rule-based tense markers, prepositions and a hard-coded word order = they are bona fide languages • Creole rules may bear no strong resemblance to the other ancestral languages in the mix, nor to the dominant language, nor to the native language • BUT they do bear a striking resemblance to other creoles which have arisen in other situations on other places on the planet!

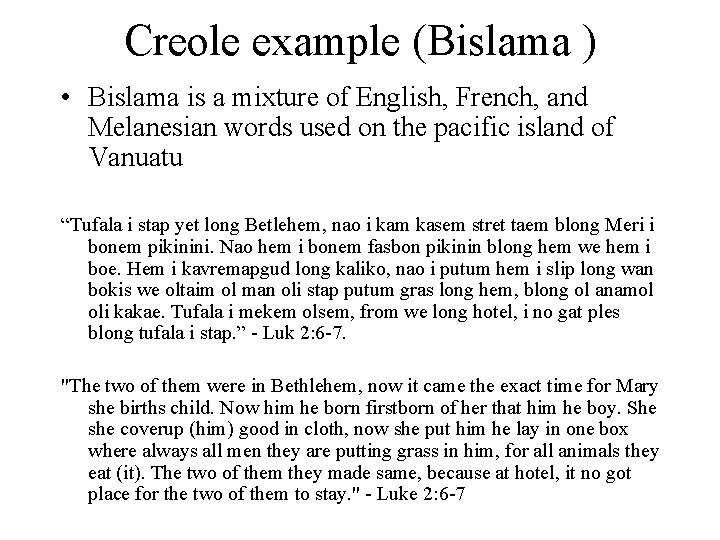

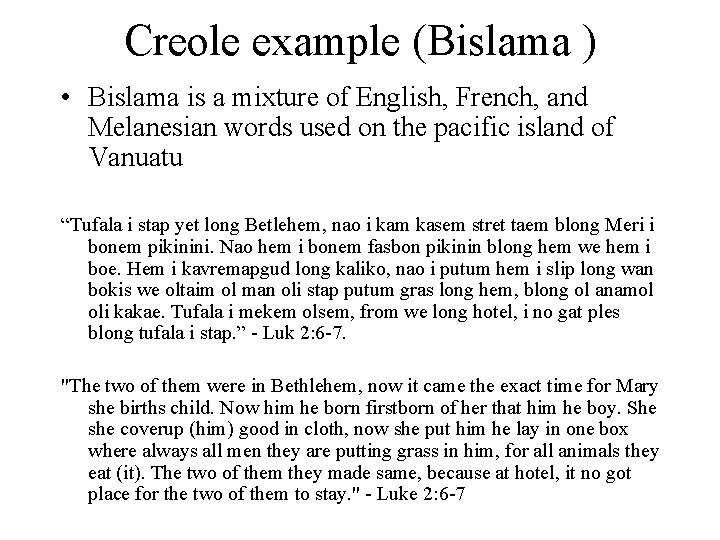

Creole example (Bislama ) • Bislama is a mixture of English, French, and Melanesian words used on the pacific island of Vanuatu “Tufala i stap yet long Betlehem, nao i kam kasem stret taem blong Meri i bonem pikinini. Nao hem i bonem fasbon pikinin blong hem we hem i boe. Hem i kavremapgud long kaliko, nao i putum hem i slip long wan bokis we oltaim ol man oli stap putum gras long hem, blong ol anamol oli kakae. Tufala i mekem olsem, from we long hotel, i no gat ples blong tufala i stap. ” - Luk 2: 6 -7. "The two of them were in Bethlehem, now it came the exact time for Mary she births child. Now him he born firstborn of her that him he boy. She she coverup (him) good in cloth, now she put him he lay in one box where always all men they are putting grass in him, for all animals they eat (it). The two of them they made same, because at hotel, it no got place for the two of them to stay. " - Luke 2: 6 -7

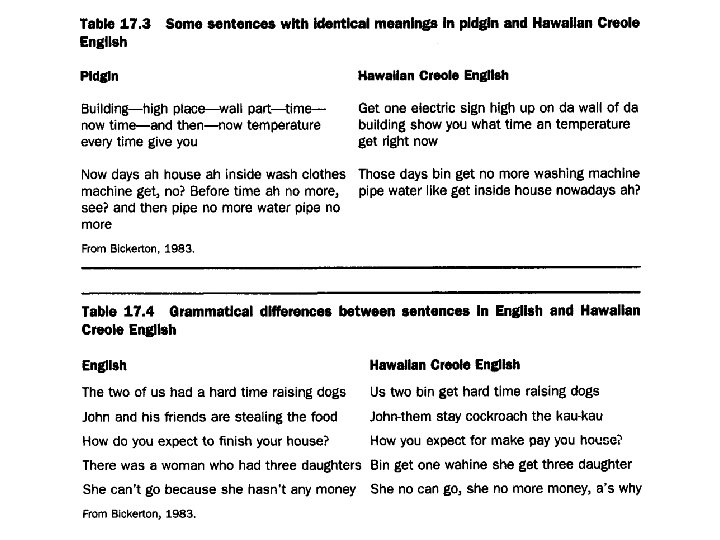

Case study: Hawaii • Creolization happened quite recently (just at the end of the last century) in Hawaii, when plantations boomed and uneducated plantations workers were brought in from around the world – Some of their children- who were raised with pidgin as their first language- are still alive, and have been studied by linguist Derek Bickerton – Hawaiian Creole includes rule-based tense markers, prepositions and a hard-coded word order

The claim • Bickerton's claim- not without critics, but with good evidence- is that the children exposed to the pidgin were the source of its regularization • The suggestion is that there are ‘default settings’ on language which children are innately drawn to use (UG? ), even if they have to invent the language in doing so, in the absence of a compelling reason to use other settings – The pre-linguistic infant is thus seen as a bottleneck which places strong constraints on what is possible in language, and which may be the source of the regularities we see across languages

What is language acquisition

What is language acquisition Putting two words together

Putting two words together Together

Together Putting it all together motion answer key

Putting it all together motion answer key Letters put together

Letters put together Package mypackage; class first { /* class body */ }

Package mypackage; class first { /* class body */ } Strategic organization means putting a speech together

Strategic organization means putting a speech together Practice putting it all together part 1 fill in the blank

Practice putting it all together part 1 fill in the blank Why we all have

Why we all have Putting it all together

Putting it all together Putting the pieces together case study answer key

Putting the pieces together case study answer key Putting things together is called

Putting things together is called Language acquisition and language learning

Language acquisition and language learning What fires together wires together

What fires together wires together Putting-out system

Putting-out system What is nasreen putting chocolate on

What is nasreen putting chocolate on When was the loom invented

When was the loom invented Proletarianization ap euro

Proletarianization ap euro Pricing strategies in marketing

Pricing strategies in marketing Putting objects in perspective

Putting objects in perspective Oncology nursing society putting evidence into practice

Oncology nursing society putting evidence into practice The order of putting on ppe

The order of putting on ppe Putting fractions in order

Putting fractions in order Putting people first 2007

Putting people first 2007 Putting-out system

Putting-out system Classify the polynomial

Classify the polynomial Putting the enterprise into the enterprise system

Putting the enterprise into the enterprise system