Labor Market Agglomeration Economies Shihe Fu fushswufe edu

Labor Market Agglomeration Economies Shihe Fu fush@swufe. edu. cn Southwestern University of Finance and Economics Summer School on Socioeconomic Inequality 2016 · Jinan University 1

Outline § Concepts of business agglomeration and labor market agglomeration economies § Micro-foundations of labor market agglomeration economies § Empirical evidence § Causal identification in empirical agglomeration economies studies § New research topics 2

Part 1: Concept § Cities areas with high-density population (or concentration of people and firms in limited geographic areas) § The benefit of such concentration is called agglomeration economies § The reason why cities exist 3

Business agglomeration economies § Localization Economies: the benefit from the concentration of same-industry firms in a city (economies of scale external to a firm but internal to an industry) § Urbanization Economies: the benefit from the concentration of different-industry firms in a city (economies of scale external to an industry but internal to a city) Hoover (1937) (Location Theory and the Shoe and Leather Industries) 4

Localization economies § Input sharing § Labor market pooling (matching and statistical economies) § Information or knowledge spillovers (learning) § Specialization (Smithian economies) § Competition (Porter) In dynamic context: Marshallian-Arrow-Romer (MAR) externalities (Glaeser et al. , 1992) (Growth in cities, JPE) 5

Urbanization economies § First stage: scale economies external to any industry but internal to a city, resulting from the general level of city economy. Measured by city size (population). (Hoover, 1937, 1971) , Henderson (1986) § Second stage: resulting from overall local urban scale and diversity (Henderson et al. , 1995) § Third stage: resulting from industrial diversity In dynamic context: Jacobs externalities, Jane Jacobs (1961, 1969); Glaeser et al. (1992) 6

Urbanization economies: micro-foundations § Jacobs externalities (effect of industrial diversity) Cross-industry fertilization Promote innovation and urban growth § Statistical economies in product and labor markets Unemployment stability Lower frictional unemployment § Input sharing § Economies of scope 7

Three important survey articles § Duranton and Diego, 2004, Microfoundations of urban agglomeration economies, Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, vol. 4 § Rosenthal and Strange, 2004, Evidence on the nature and sources of agglomeration economies, vol. 4 § Combes and Gobillon, 2014, The empirics of agglomeration economies, vol. 5 8

Labor market agglomeration economies § Benefits from the concentration of workers (employment) in cities. Such benefits increase workers’ productivity and therefore wages § Labor market localization economies: Benefits from concentration of workers in the same industry (occupation) in a city. In dynamic context, Marshallian externalities in labor markets § Labor market urbanization economies: Benefits from concentration of workers in different industries (occupations) in a city. In dynamic context, Jacobs 9 externalities in labor markets

Part 2: Micro-foundations for labor market agglomeration economies § Labor market pooling effect: a large, dense labor market increases matching quality, decreases search friction and frictional unemployment 10

Learning § Human capital externalities (knowledge spillovers): information exchange and knowledge spillovers through formal and informal social interactions, such as communication, imitation, peer effects, learning by doing 11

Lucas (1988): On the mechanism of economic development 12

Networking § Social network (social capital): help reaching better information and resources, such as weak ties and strong ties 13

Part 3: Empirical evidence of labor market agglomeration economies § Urban wage premium: Glaeser and Mare (2001), Moretti (2004), Rosenthal and Strange (2006), Combes et al. (2008)… § Doubling city size increases wage by 4. 5 -11%, conditional on observed characteristics 14

Why do cities pay more? § Yanknow (2006): Why do cities pay more? An empirical examination of some competing theories of the urban wage premium) • Cost of living • Ability sorting • Firm-level productivity (business agglomeration) • Learning (human capital accumulation, wage growth) • Coordination or matching (between-job wage growth) • uses NLSY 79 data, 19% wage premium, 2/3 due to sorting 15

Empirical evidence of Marshallian labor market externalities § Boston MSA (Fu, 2007): significant effect, semielasticity of occupation specialization in a county is 0. 17 § Netherlands (Groot, et al. 2014): doubling the local share of a (two-digit) industry employment results in a 2. 9 percent higher productivity. § Italy (Andini, et al. , 2012, Marshallian Labor Market Pooling: Evidence From Italy): focus on labor market pooling, find evidence of high turn-over, on-the-job learning in dense labor market, but overall magnitude is 16 small.

Empirical evidence on human capital externalities § Moretti (2004, Human capital externalities in cities, vol. 4): a one year increase in average education in a city increases individual wage by 3 -5%; a one percentage point increase in city college share raises average wage by 0. 6 -1. 2% Rosenthal and Strange (2006) : the elasticity of wage with respect to the number of workers within five miles is roughly 4. 5 percent, mainly due to the 17 presence of college graduates

Spatial decay of labor market agglomeration economies (localized agglomeration effect) § Business agglomeration economies decay with distance (Rosenthal and Strange, 2003, Geography, Industrial Organization, and Agglomeration, RESTAT ; Duranton and Overman, 2005 ) § Labor market agglomeration economies decay with distance: Fu (2007): human capital externalities decay rapidly after 6 miles away from a block centriod Rosenthal and Strange (2006): decay rapidly after 5 miles 18

Evidence from firm productivity, city size § Supportive evidence • Sveikauskas (1975): productivity is higher in larger cities • Segal (1976): productivity is 8% higher in cities above 2 millions • Moomaw (1985): 7% • Baldwin et al. (2007): 7. 7% in Canada § No or weak evidence • Carlino (1979): net diseconomies of city size • Nakamura (1985): small urbanization economies in Japan • Henderson (1986): little urbanization economies • Baldwin et al. (2008): negative effect of city size

Evidence from firm productivity, diversity § Supportive evidence • Glaeser et al. (1992): diversity promotes urban employment growth • Henderson et al. (1995): attract new industries § No or weak evidence • Henderson (2003): no urbanization economies

Summary of empirical evidence § mostly from developed countries § mostly on effect of city size (urbanization economies or city-size wage premium) § mostly on urban workers

Part 4: Causal identification strategies

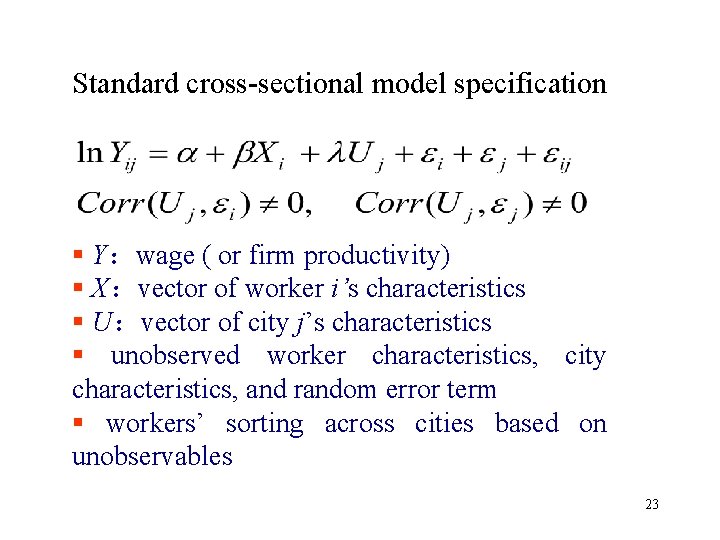

Standard cross-sectional model specification § Y:wage ( or firm productivity) § X:vector of worker i’s characteristics § U:vector of city j’s characteristics § unobserved worker characteristics, city characteristics, and random error term § workers’ sorting across cities based on unobservables 23

1. Control for individual fixed effects using panel data (Glaeser and Mare, 2001, Cities and skills) 24

2. Exogenous geographic feature as IV (Rosenthal and Strange, 2008, The Attenuation of Human Capital Spillovers: A Manhattan Skyline Approach ): the fraction of land underlain by sedimentary rock, designated as seismic hazard or landslide hazard as IV for total employment The presence of a Land-grant college in a city (in 1862) as IV for college share (Moretti, 2005) Long-lagged city size or college share as IV 25

3. Observationally equivalent individuals; microgeographic unit (census block) (Bayer and Ross, 2006, Identifying Individual and Group Effects in the Presence of Sorting: A Neighborhood Effects Application): there is no block-level correlation in unobserved attributes among block residents, after taking into account the broader neighborhood reference group such as block group. 26

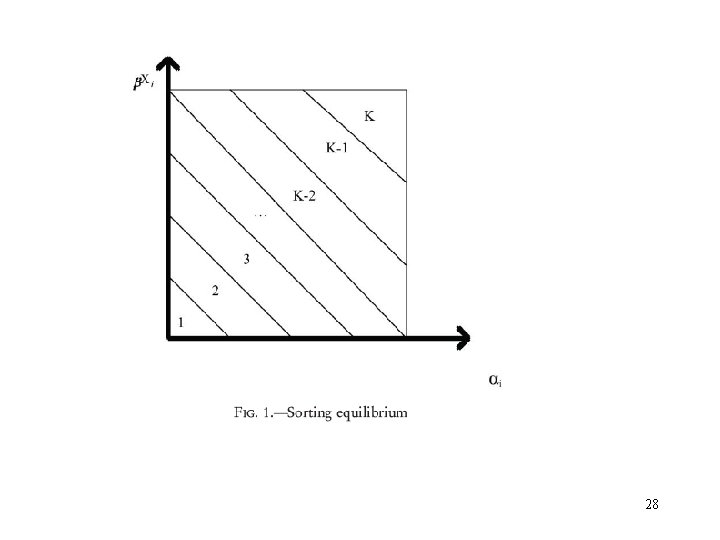

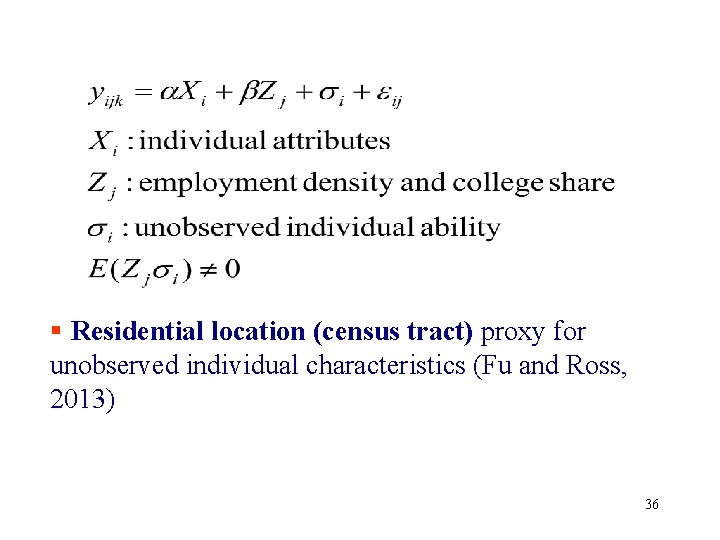

4. Residential location (census tract fixed effects) proxy for unobserved individual characteristics (Fu and Ross, 2013) 27

28

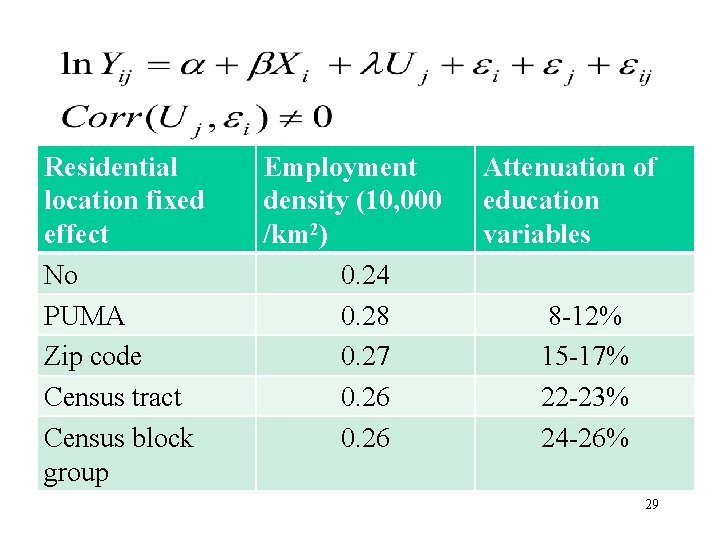

Residential location fixed effect No PUMA Zip code Census tract Census block group Employment density (10, 000 /km 2) 0. 24 0. 28 0. 27 0. 26 Attenuation of education variables 8 -12% 15 -17% 22 -23% 24 -26% 29

Part 5. New research topics on labor market agglomeration economies § New identification strategies § What kind of social interaction generates knowledge spillovers? § Urban sprawl, commuting, and social interaction § Agglomeration economies, innovation, entreprenuership § Agglomeration economies by groups (CEO, rural migrants…) § Agglomeration economies, social interaction, and ICT § Internal migration, spatial equilibrium and quality of life in cities § Agglomeration economies in cities of developing 30 countries

What is inside the black box of social interaction? § Charlot and Duranton, 2004, Communication externalities in cities, JUE: In larger and more educated cities, workers communicate more and in turn this has a positive effect on their wages. 13 to 22% of the effects of a more educated and larger city on wages percolate through this channel. (survey questions about communications within a firm, outside of a firm, and usage of media) 31

Cities and skills § O*NET data § Skill concentration in cities: large cities are more skilled § Return to skill varies across cities: higher wage premium for stronger cognitive and people skills but not for motor skills and physical strength in large cities (Bacolod, Blume, and Strange, 2009, Skills in the city, JUE) 32

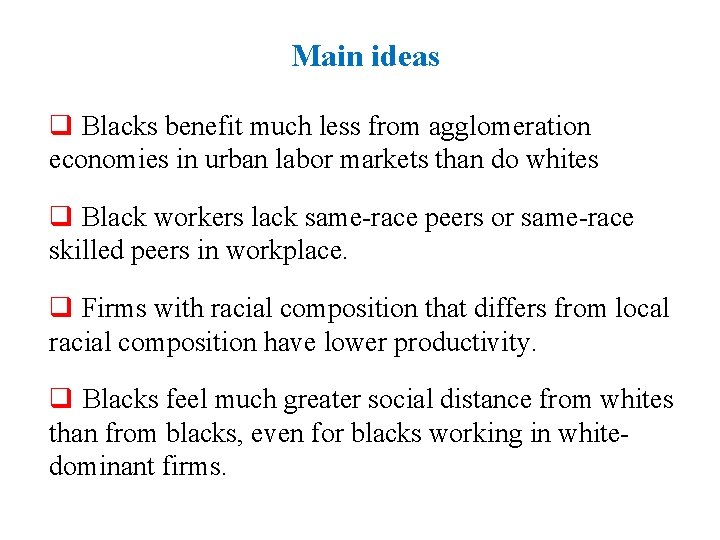

Why do African Americans benefit less from labor market agglomeration economies than do whites? § Ananat, Fu, and Ross, 2013, Race-specific agglomeration economies: social distance and the black-white wage gap, NBER Working Paper #18933 33

Main ideas q Blacks benefit much less from agglomeration economies in urban labor markets than do whites q Black workers lack same-race peers or same-race skilled peers in workplace. q Firms with racial composition that differs from local racial composition have lower productivity. q Blacks feel much greater social distance from whites than from blacks, even for blacks working in whitedominant firms.

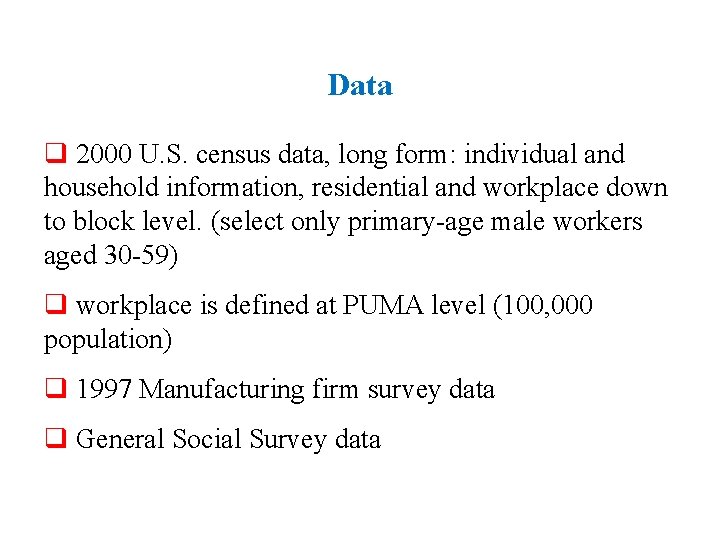

Data q 2000 U. S. census data, long form: individual and household information, residential and workplace down to block level. (select only primary-age male workers aged 30 -59) q workplace is defined at PUMA level (100, 000 population) q 1997 Manufacturing firm survey data q General Social Survey data

§ Residential location (census tract) proxy for unobserved individual characteristics (Fu and Ross, 2013) 36

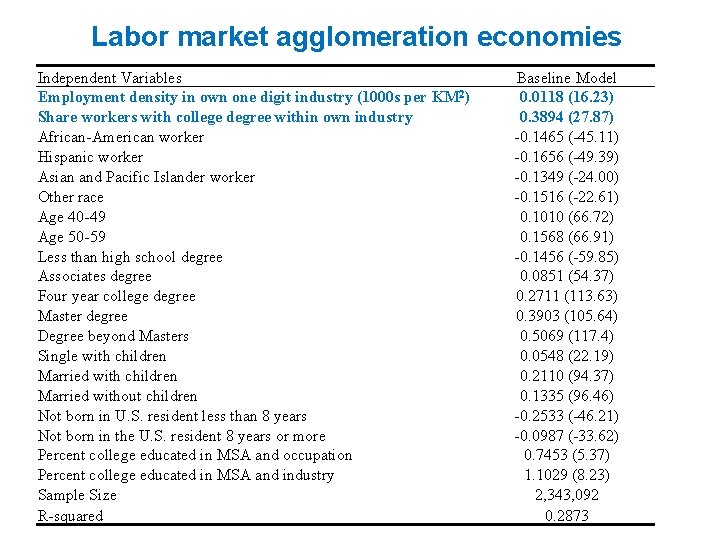

Labor market agglomeration economies Independent Variables Employment density in own one digit industry (1000 s per KM 2) Share workers with college degree within own industry African-American worker Hispanic worker Asian and Pacific Islander worker Other race Age 40 -49 Age 50 -59 Less than high school degree Associates degree Four year college degree Master degree Degree beyond Masters Single with children Married without children Not born in U. S. resident less than 8 years Not born in the U. S. resident 8 years or more Percent college educated in MSA and occupation Percent college educated in MSA and industry Sample Size R-squared Baseline Model 0. 0118 (16. 23) 0. 3894 (27. 87) -0. 1465 (-45. 11) -0. 1656 (-49. 39) -0. 1349 (-24. 00) -0. 1516 (-22. 61) 0. 1010 (66. 72) 0. 1568 (66. 91) -0. 1456 (-59. 85) 0. 0851 (54. 37) 0. 2711 (113. 63) 0. 3903 (105. 64) 0. 5069 (117. 4) 0. 0548 (22. 19) 0. 2110 (94. 37) 0. 1335 (96. 46) -0. 2533 (-46. 21) -0. 0987 (-33. 62) 0. 7453 (5. 37) 1. 1029 (8. 23) 2, 343, 092 0. 2873

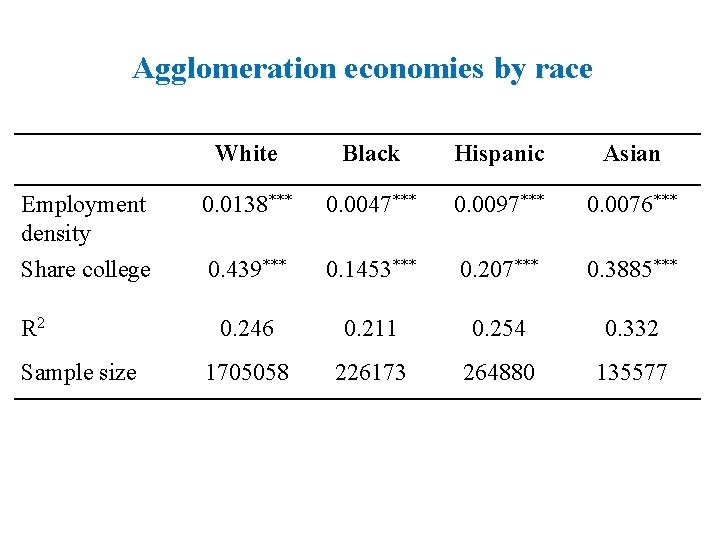

Agglomeration economies by race White Black Hispanic Asian Employment density 0. 0138*** 0. 0047*** 0. 0097*** 0. 0076*** Share college 0. 439*** 0. 1453*** 0. 207*** 0. 3885*** 0. 246 0. 211 0. 254 0. 332 1705058 226173 264880 135577 R 2 Sample size

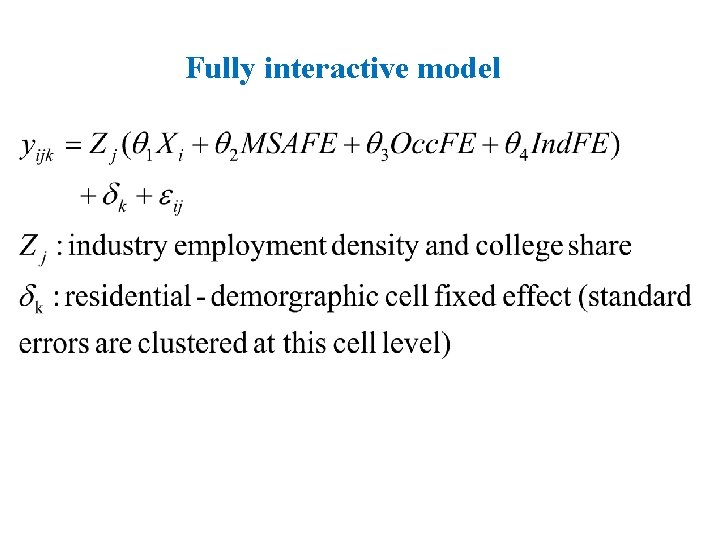

Fully interactive model

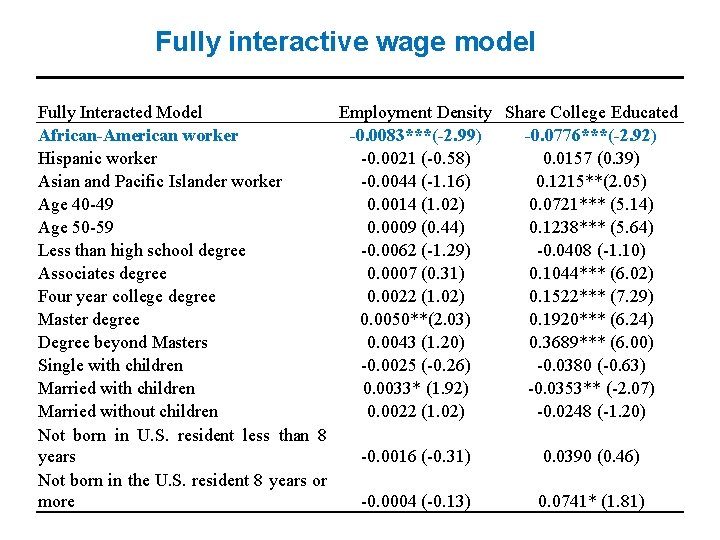

Fully interactive wage model Fully Interacted Model Employment Density Share College Educated African-American worker -0. 0083***(-2. 99) -0. 0776***(-2. 92) Hispanic worker -0. 0021 (-0. 58) 0. 0157 (0. 39) Asian and Pacific Islander worker -0. 0044 (-1. 16) 0. 1215**(2. 05) Age 40 -49 0. 0014 (1. 02) 0. 0721*** (5. 14) Age 50 -59 0. 0009 (0. 44) 0. 1238*** (5. 64) Less than high school degree -0. 0062 (-1. 29) -0. 0408 (-1. 10) Associates degree 0. 0007 (0. 31) 0. 1044*** (6. 02) Four year college degree 0. 0022 (1. 02) 0. 1522*** (7. 29) Master degree 0. 0050**(2. 03) 0. 1920*** (6. 24) Degree beyond Masters 0. 0043 (1. 20) 0. 3689*** (6. 00) Single with children -0. 0025 (-0. 26) -0. 0380 (-0. 63) Married with children 0. 0033* (1. 92) -0. 0353** (-2. 07) Married without children 0. 0022 (1. 02) -0. 0248 (-1. 20) Not born in U. S. resident less than 8 years -0. 0016 (-0. 31) 0. 0390 (0. 46) Not born in the U. S. resident 8 years or more -0. 0004 (-0. 13) 0. 0741* (1. 81)

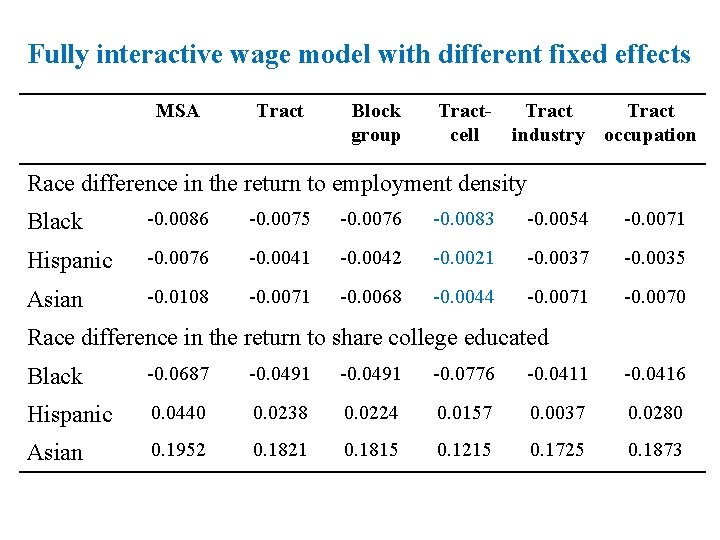

Fully interactive wage model with different fixed effects MSA Tract Block group Tractcell Tract industry occupation Race difference in the return to employment density Black -0. 0086 -0. 0075 -0. 0076 -0. 0083 -0. 0054 -0. 0071 Hispanic -0. 0076 -0. 0041 -0. 0042 -0. 0021 -0. 0037 -0. 0035 Asian -0. 0108 -0. 0071 -0. 0068 -0. 0044 -0. 0071 -0. 0070 Race difference in the return to share college educated Black -0. 0687 -0. 0491 -0. 0776 -0. 0411 -0. 0416 Hispanic 0. 0440 0. 0238 0. 0224 0. 0157 0. 0037 0. 0280 Asian 0. 1952 0. 1821 0. 1815 0. 1215 0. 1725 0. 1873

African-Americans tend to make different residential, workplace, and commuting choices than do whites? (Estimate the slope model by: ) § Central city vs. suburban residents § Share of blacks in a residential tract above/below MSA average § Work in central city vs. in suburbs § Workplace employment density above/below MSA average § Workplace college share above/below MSA average § Work in high spillover (or low spillover ) industries § Mass transit users, automobile users

Why do African Americans benefit less from labor market agglomeration economies? § Unobserved lower ability § Spatial mismatch § Residential segregation § Workplace segregation or race-specific social network (Bokenblom and Ekblod, 2007; Mas and Moretti, 2006; Hellerstein et al. 2008, 2009): social interactions are race specific

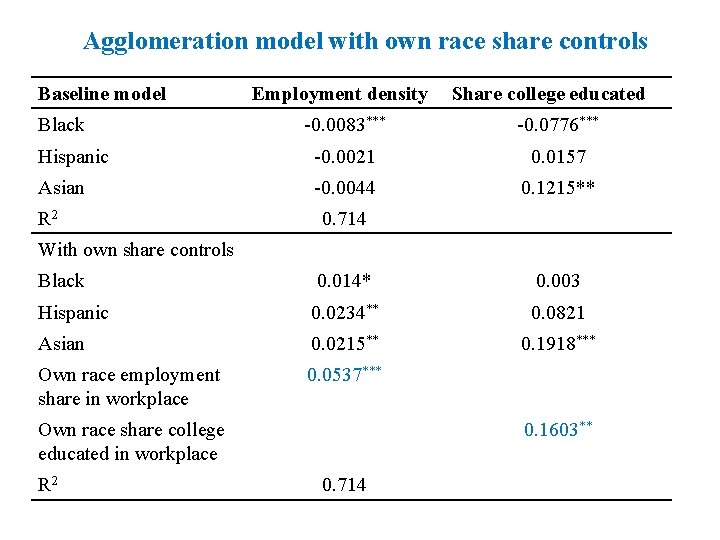

Agglomeration model with own race share controls Baseline model Black Employment density Share college educated -0. 0083*** -0. 0776*** Hispanic -0. 0021 0. 0157 Asian -0. 0044 0. 1215** R 2 0. 714 With own share controls Black 0. 014* 0. 003 Hispanic 0. 0234** 0. 0821 Asian 0. 0215** 0. 1918*** Own race employment share in workplace 0. 0537*** Own race share college educated in workplace R 2 0. 1603** 0. 714

Agglomeration model with own race share controls, robustness Baseline model Baseline Non-linear agglomeration Workplace racial composition Blacknonblack shares -0. 0081*** -0. 0072*** -0. 0083*** 0. 014* 0. 0078 0. 0124 0. 0332*** 0. 0537*** 0. 0385*** 0. 0493*** 0. 0639*** -0. 0787*** -0. 0682*** -0. 0776*** Employment density Black -0. 0083*** With own race share controls Black Own race emp. share Share college educated Black -0. 0776*** With own race share controls Black -0. 003 -0. 0233 -0. 031 -0. 0783 Own race college share 0. 1603** 0. 1929*** 0. 1933*** 0. 2276**

Total Factor Productivity Models q 1997 Census of Manufactures establishments data q Use the decennial census to estimate the fraction of workers in 3 digit industry-zip code cells with a four year college degree and the fraction that fall into each race and ethnicity category. q Calculate average worker exposure to own race workers at other firms in the workplace PUMA for each firm type (industry-zip code cell) for all workers and for college educated workers q Verify that racial differences and own race effects hold for a subsample manufacturing workers and TFP models

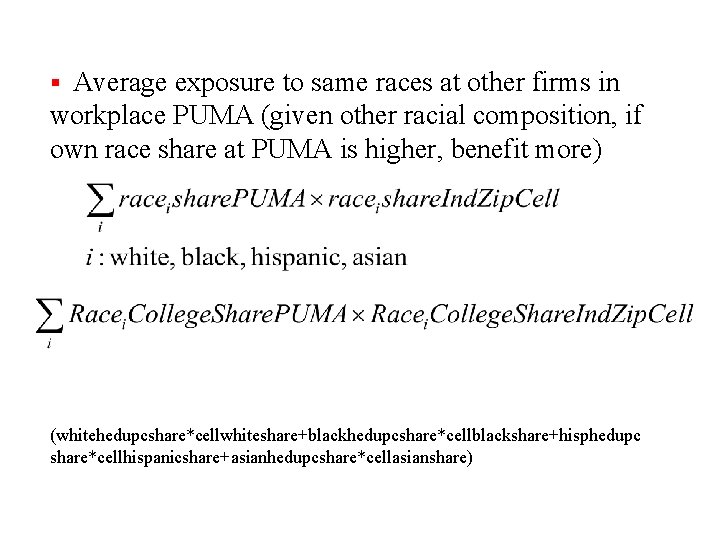

§ Average exposure to same races at other firms in workplace PUMA (given other racial composition, if own race share at PUMA is higher, benefit more) (whitehedupcshare*cellwhiteshare+blackhedupcshare*cellblackshare+hisphedupc share*cellhispanicshare+asianhedupcshare*cellasianshare)

TFP models with agglomeration and race exposure Variables Transloginteraction Translog-interaction with mean tract FE Employment density 0. 0288*** -0. 0012 -0. 0001 Own race exposure -0. 065 -0. 0567 Density*own race exposure 0. 0919** 0. 0913*** 0. 096 0. 0253 Own race college exposure 0. 0534 0. 0236 Share college*own race college exposure 0. 178 0. 2115* 0. 909 111695 111538 Share college R 2 Sample size 0. 2033*** Dependent variable: log value added

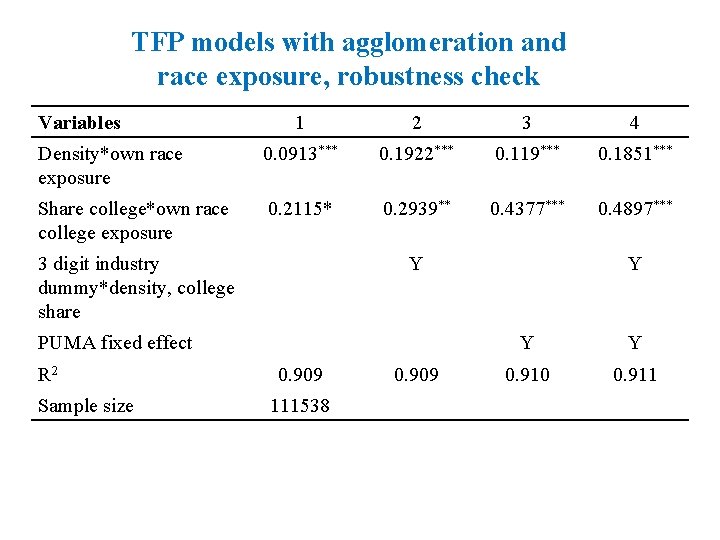

TFP models with agglomeration and race exposure, robustness check Variables 1 2 3 4 Density*own race exposure 0. 0913*** 0. 1922*** 0. 119*** 0. 1851*** Share college*own race college exposure 0. 2115* 0. 2939** 0. 4377*** 0. 4897*** 3 digit industry dummy*density, college share Y PUMA fixed effect R 2 Sample size 0. 909 111538 0. 909 Y Y Y 0. 910 0. 911

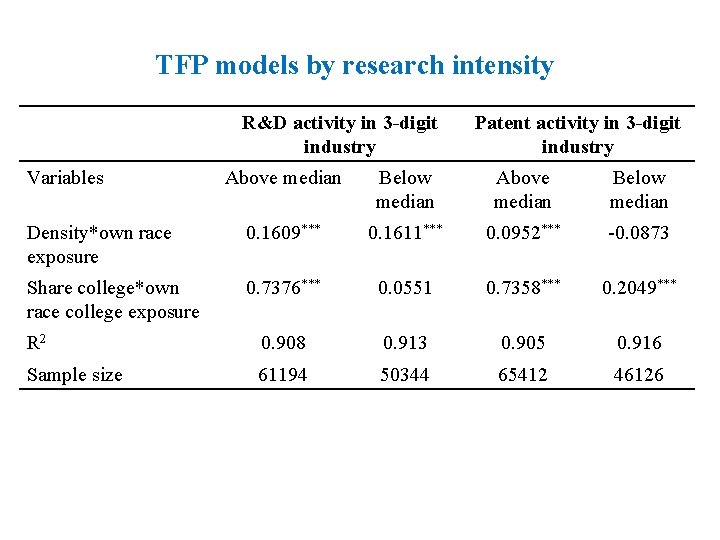

TFP models by research intensity R&D activity in 3 -digit industry Variables Patent activity in 3 -digit industry Above median Below median Density*own race exposure 0. 1609*** 0. 1611*** 0. 0952*** -0. 0873 Share college*own race college exposure 0. 7376*** 0. 0551 0. 7358*** 0. 2049*** R 2 0. 908 0. 913 0. 905 0. 916 Sample size 61194 50344 65412 46126

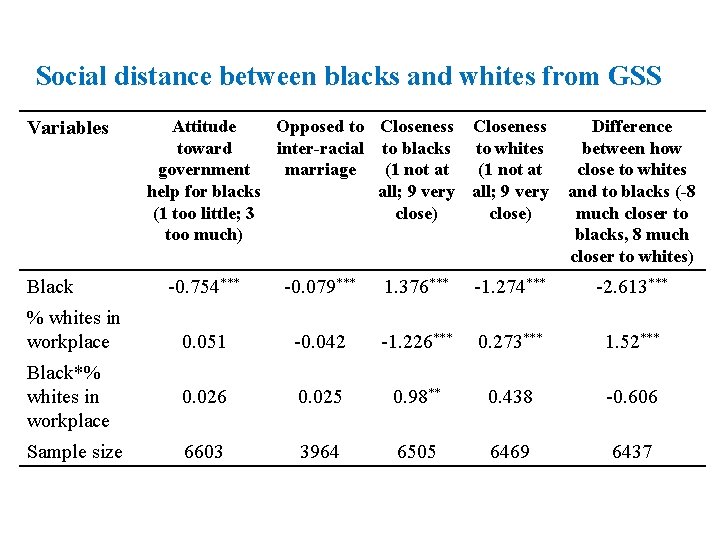

Social distance between blacks and whites from GSS Variables Black Attitude Opposed to Closeness toward inter-racial to blacks to whites government marriage (1 not at help for blacks all; 9 very (1 too little; 3 close) too much) Difference between how close to whites and to blacks (-8 much closer to blacks, 8 much closer to whites) -0. 754*** -0. 079*** 1. 376*** -1. 274*** -2. 613*** 0. 051 -0. 042 -1. 226*** 0. 273*** 1. 52*** Black*% whites in workplace 0. 026 0. 025 0. 98** 0. 438 -0. 606 Sample size 6603 3964 6505 6469 6437 % whites in workplace

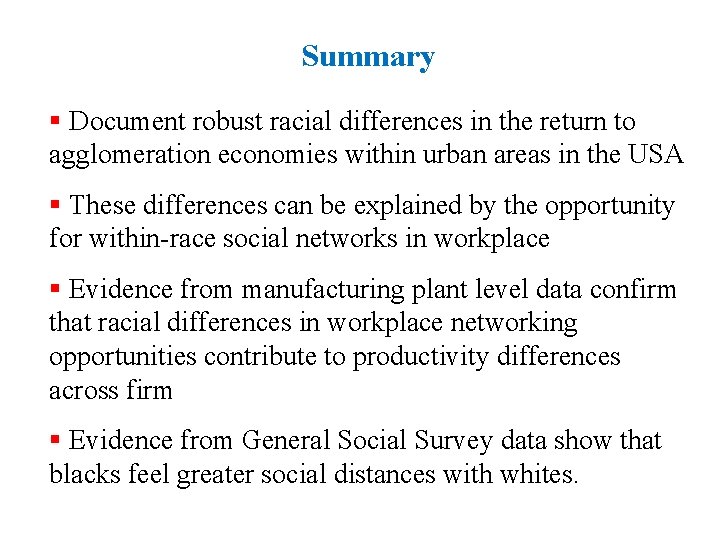

Summary § Document robust racial differences in the return to agglomeration economies within urban areas in the USA § These differences can be explained by the opportunity for within-race social networks in workplace § Evidence from manufacturing plant level data confirm that racial differences in workplace networking opportunities contribute to productivity differences across firm § Evidence from General Social Survey data show that blacks feel greater social distances with whites.

Do rural migrants benefit from urban labor market agglomeration economies? Evidence from Chinese cities Yang, Li, and Fu (2016)

Data § 2004 manufacturing firm census data: total employment, by education § 2005 inter-census population survey (1/5 of the 1% sample) § Merge by city-industry link (two-digit industries) (Moretti, 2004) § Key variables of agglomeration economies: • log(Emp): total employment in a same city-industry cell • College. Share: college share in a same city-industry cell (human capital externality)

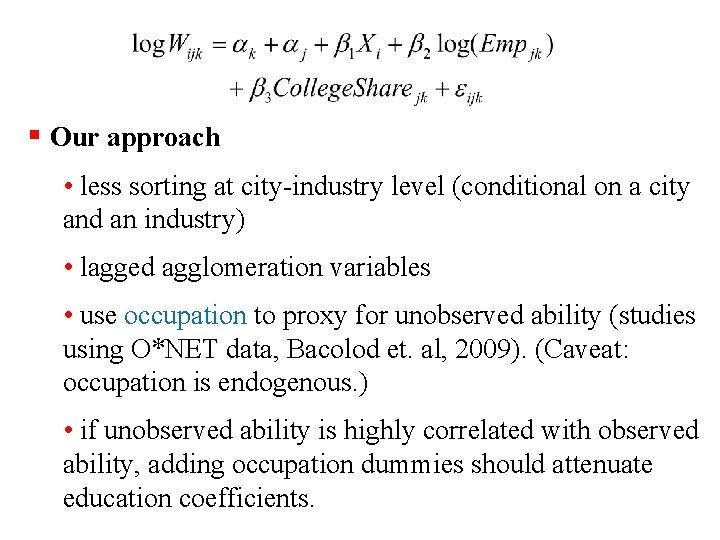

Model

Identification issues

§ Our approach • less sorting at city-industry level (conditional on a city and an industry) • lagged agglomeration variables • use occupation to proxy for unobserved ability (studies using O*NET data, Bacolod et. al, 2009). (Caveat: occupation is endogenous. ) • if unobserved ability is highly correlated with observed ability, adding occupation dummies should attenuate education coefficients.

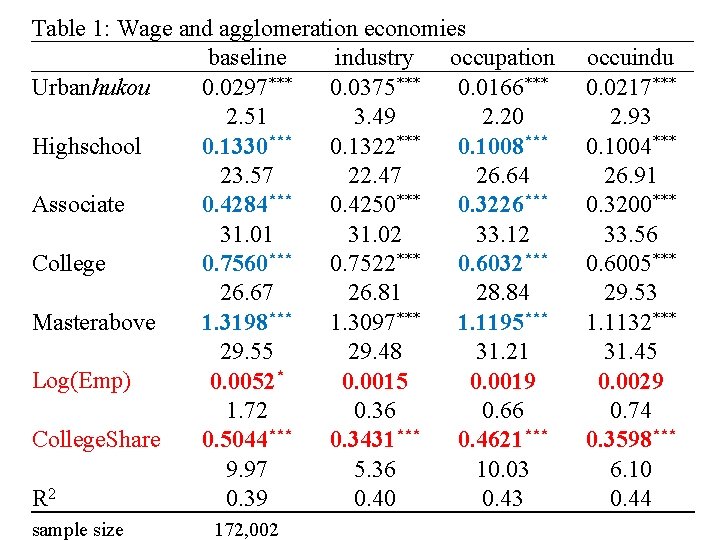

Table 1: Wage and agglomeration economies baseline industry occupation Urbanhukou 0. 0297*** 0. 0375*** 0. 0166*** 2. 51 3. 49 2. 20 Highschool 0. 1330*** 0. 1322*** 0. 1008*** 23. 57 22. 47 26. 64 Associate 0. 4284*** 0. 4250*** 0. 3226*** 31. 01 31. 02 33. 12 College 0. 7560*** 0. 7522*** 0. 6032*** 26. 67 26. 81 28. 84 Masterabove 1. 3198*** 1. 3097*** 1. 1195*** 29. 55 29. 48 31. 21 Log(Emp) 0. 0052* 0. 0015 0. 0019 1. 72 0. 36 0. 66 College. Share 0. 5044*** 0. 3431*** 0. 4621*** 9. 97 5. 36 10. 03 R 2 0. 39 0. 40 0. 43 sample size 172, 002 occuindu 0. 0217*** 2. 93 0. 1004*** 26. 91 0. 3200*** 33. 56 0. 6005*** 29. 53 1. 1132*** 31. 45 0. 0029 0. 74 0. 3598*** 6. 10 0. 44

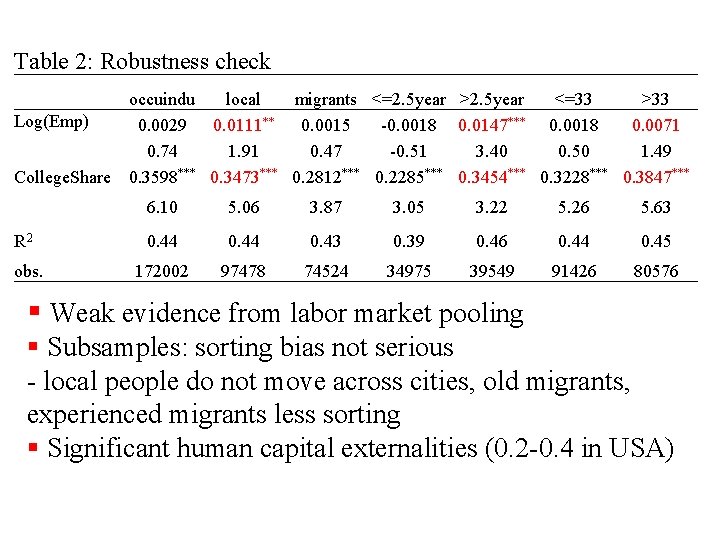

Table 2: Robustness check occuindu local migrants <=2. 5 year >2. 5 year <=33 >33 Log(Emp) 0. 0029 0. 0111** 0. 0015 -0. 0018 0. 0147*** 0. 0018 0. 0071 0. 74 1. 91 0. 47 -0. 51 3. 40 0. 50 1. 49 College. Share 0. 3598*** 0. 3473*** 0. 2812*** 0. 2285*** 0. 3454*** 0. 3228*** 0. 3847*** R 2 obs. 6. 10 5. 06 3. 87 3. 05 3. 22 5. 26 5. 63 0. 44 0. 43 0. 39 0. 46 0. 44 0. 45 172002 97478 74524 34975 39549 91426 80576 § Weak evidence from labor market pooling § Subsamples: sorting bias not serious - local people do not move across cities, old migrants, experienced migrants less sorting § Significant human capital externalities (0. 2 -0. 4 in USA)

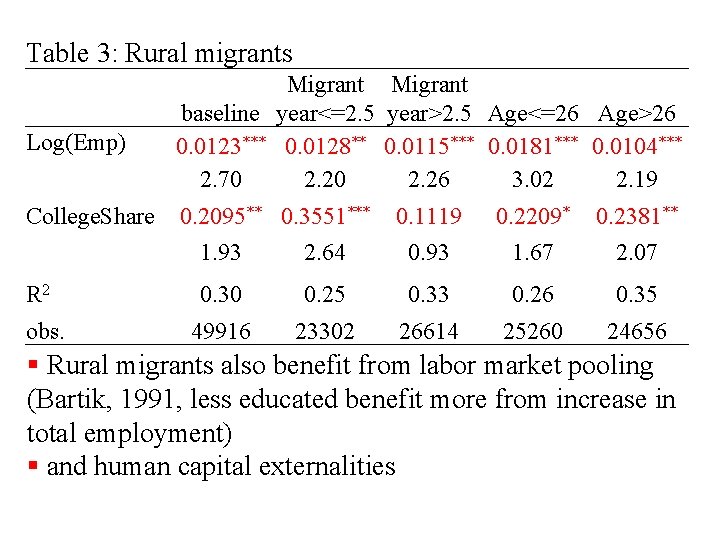

Table 3: Rural migrants Log(Emp) Migrant baseline year<=2. 5 year>2. 5 Age<=26 Age>26 0. 0123*** 0. 0128** 0. 0115*** 0. 0181*** 0. 0104*** 2. 70 2. 26 3. 02 2. 19 College. Share 0. 2095** 0. 3551*** R 2 obs. 0. 1119 0. 2209* 0. 2381** 1. 93 2. 64 0. 93 1. 67 2. 07 0. 30 0. 25 0. 33 0. 26 0. 35 49916 23302 26614 25260 24656 § Rural migrants also benefit from labor market pooling (Bartik, 1991, less educated benefit more from increase in total employment) § and human capital externalities

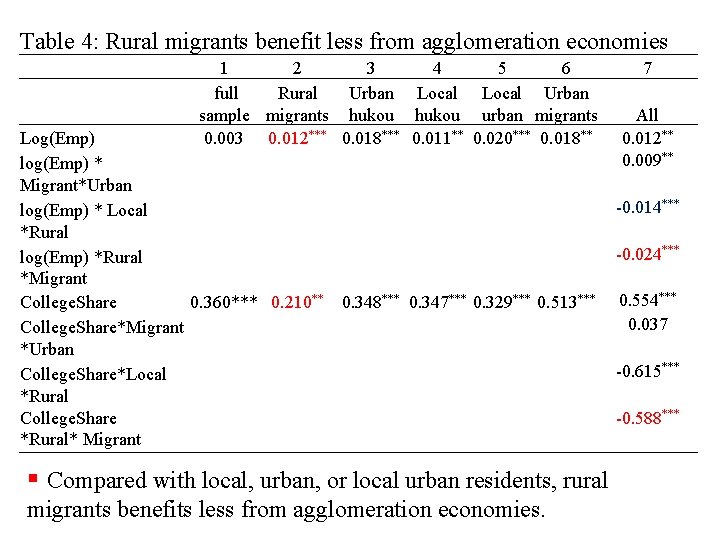

Table 4: Rural migrants benefit less from agglomeration economies 1 2 3 4 5 6 full Rural Urban Local Urban sample migrants hukou urban migrants 0. 003 0. 012*** 0. 018*** 0. 011** 0. 020*** 0. 018** Log(Emp) log(Emp) * Migrant*Urban log(Emp) * Local *Rural log(Emp) *Rural *Migrant College. Share 0. 360*** 0. 210** College. Share*Migrant *Urban College. Share*Local *Rural College. Share *Rural* Migrant 7 All 0. 012** 0. 009** -0. 014*** -0. 024*** 0. 348*** 0. 347*** 0. 329*** 0. 513*** § Compared with local, urban, or local urban residents, rural migrants benefits less from agglomeration economies. 0. 554*** 0. 037 -0. 615*** -0. 588***

Possible interpretation § Work in informal job sectors which have little spillovers? (industry fixed effect) § Low skilled, low absorptive capacity? (education categories) § Rural migrants lack of social network? (information asymmetry) § Discrimination?

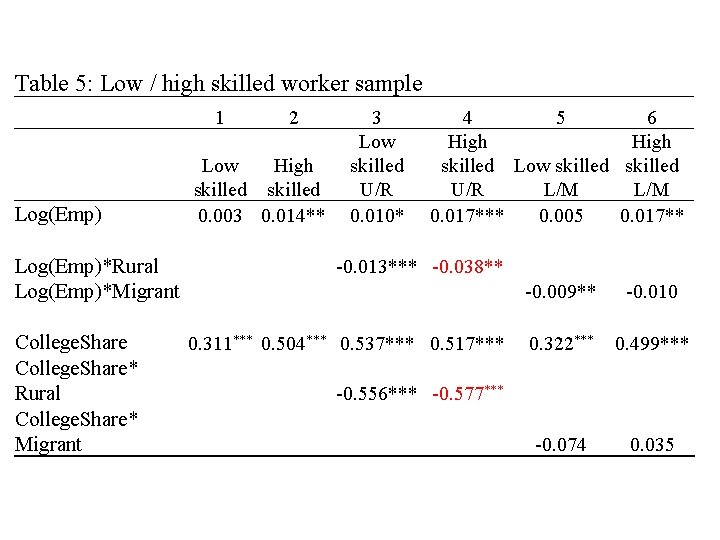

Table 5: Low / high skilled worker sample 1 Log(Emp)*Rural Log(Emp)*Migrant College. Share* Rural College. Share* Migrant 2 Low High skilled 0. 003 0. 014** 3 Low skilled U/R 0. 010* 4 5 6 High skilled Low skilled U/R L/M 0. 017*** 0. 005 0. 017** -0. 013*** -0. 038** 0. 311*** 0. 504*** 0. 537*** 0. 517*** -0. 009** -0. 010 0. 322*** 0. 499*** -0. 074 0. 035 -0. 556*** -0. 577***

Table 6: Low / high skilled worker sample, interactive model Full sample Low skilled High skilled Log(Emp) 0. 012* Log(Emp)*urban*migrant 0. 009** Log(Emp)*local*rural -0. 014*** Log(Emp)*rural*migrant -0. 024*** College. Share 0. 554*** College. Share*urban* migrant 0. 037 College. Share*local*rural -0. 615*** College. Share*rural* -0. 588*** migrant 0. 008 0. 002 -0. 007* -0. 014** 0. 538*** 0. 018*** -0. 004 -0. 019 -0. 046*** 0. 509*** -0. 093 -0. 580*** -0. 500*** 0. 053 -0. 584** -0. 503 (-1. 49) § There may exist two types of discrimination • double discrimination: local bias and urban bias

Tentative interpretation § Low skilled, informal job sector (excluded) § Rural migrants lack of social network? (information asymmetry) § Discrimination?

Tentative conclusion § Labor market agglomeration economies exist in Chinese cities. § Rural migrants benefit from labor market agglomeration economies, but much less compared with local residents with an urban hukou. § Double discrimination toward rural migrants (May be a social network effect or discrimination? )

Implications § What drives rural-urban migration and urbanization? Cities facilitate learning § What prevents rural migrants benefit from urban labor market agglomeration? Implications on urbanization and city growth § Globalization of cities, comparative advantage of manufacturing industry, and urbanization of low skilled workers? § School education versus learning through social interactions

Comments and Q&A

- Slides: 68