Knowledgebased protocols for protein structure prediction from protein

Knowledge-based protocols for protein structure prediction: from protein threading to solvent accessibility prediction and back to protein structure prediction by threading Jarek Meller Division of Biomedical Informatics, Children’s Hospital Research Foundation & Department of Biomedical Engineering, UC JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 1

Outline of the talk l l l Protein structure and complexity of conformational search: from de novo structure prediction to similarity based methods Protein structure prediction by sequence-to-structure matching (threading and fold recognition) Secondary structure and solvent accessibility prediction Improving fold recognition and de novo simulations with accurate solvent accessibility prediction A story from our backyard: predicting interaction between p. VHL and RNA Pol II JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 2

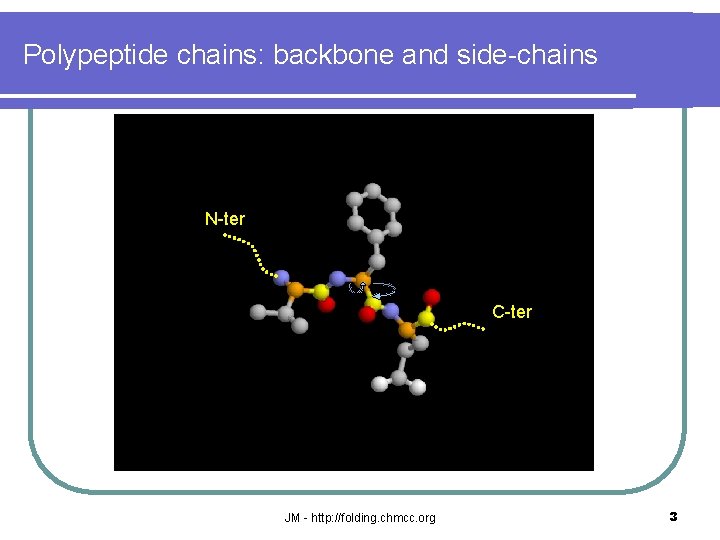

Polypeptide chains: backbone and side-chains N-ter C-ter JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 3

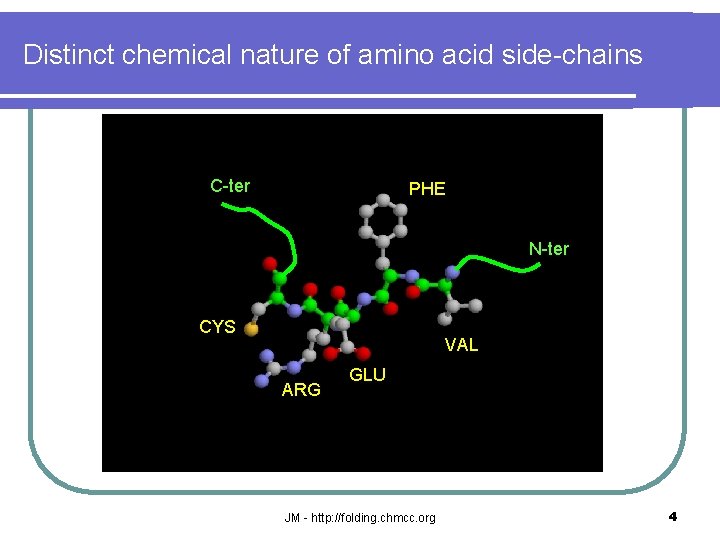

Distinct chemical nature of amino acid side-chains C-ter PHE N-ter CYS VAL ARG GLU JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 4

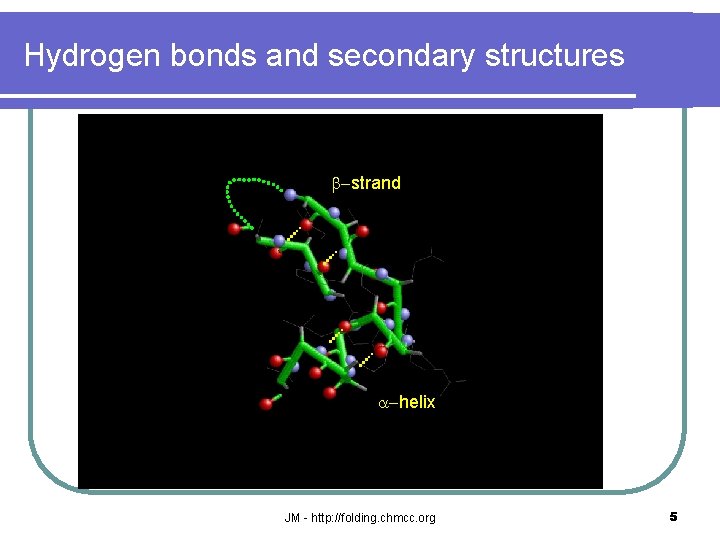

Hydrogen bonds and secondary structures b-strand a-helix JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 5

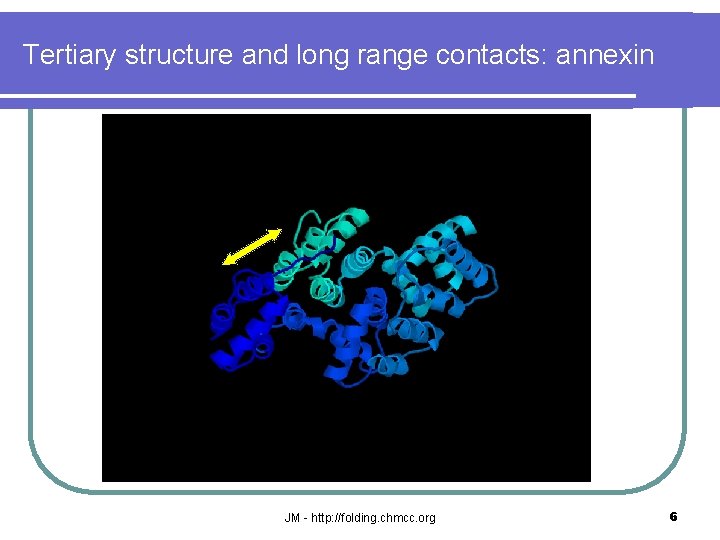

Tertiary structure and long range contacts: annexin JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 6

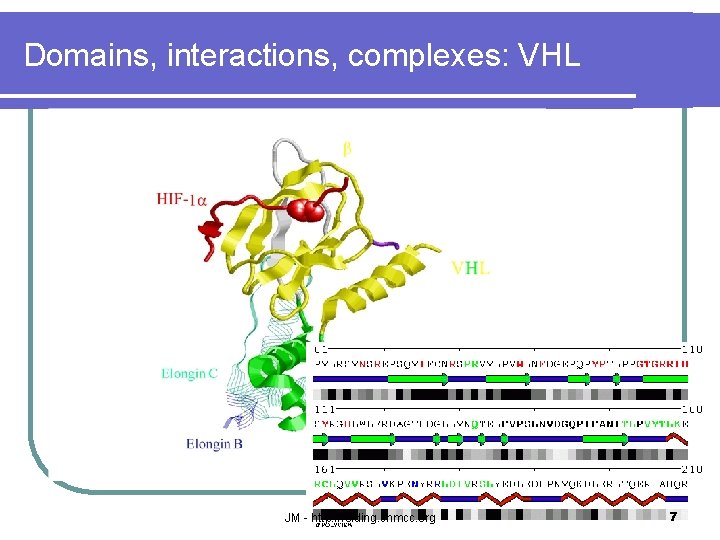

Domains, interactions, complexes: VHL JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 7

Multiple alignment and PSSM JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 8

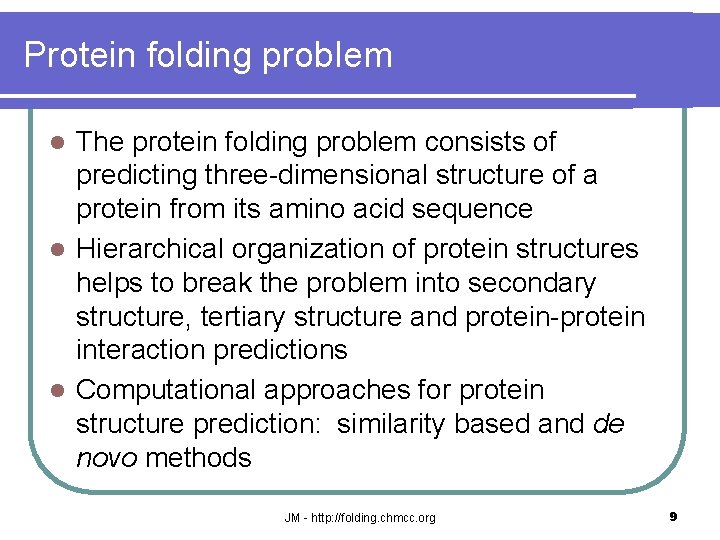

Protein folding problem The protein folding problem consists of predicting three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence l Hierarchical organization of protein structures helps to break the problem into secondary structure, tertiary structure and protein-protein interaction predictions l Computational approaches for protein structure prediction: similarity based and de novo methods l JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 9

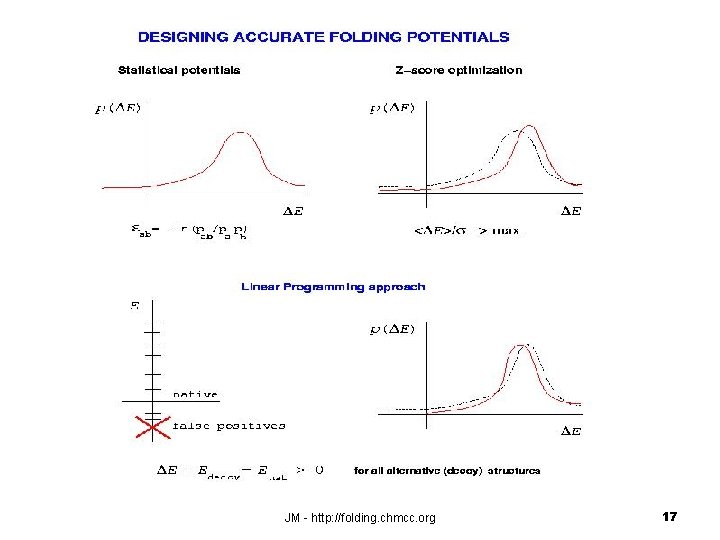

Ab initio (or de novo) folding simulations Ab initio folding simulations consist of conformational search with an empirical scoring function (“force field”) to be maximized (minimized) l Computational bottleneck: exponential search space and sampling problem (global optimization!) l Fundamental problem: inaccuracy of empirical force fields and scoring functions (folding potentials) l Importance of mixed protocols, such as Rosetta by D. Baker and colleagues (Monte Carlo fragment assembly) l JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 10

Similarity based approaches to structure prediction: from sequence alignment to fold recognition High level of redundancy in biology: sequence similarity is often sufficient to use the “guilt by association” rule: if similar sequence then similar structure and function l Multiple alignments and family profiles can detect evolutionary relatedness with much lower sequence similarity, hard to detect with pairwise sequence alignments: Psi-BLAST by S. Altschul et. al. l Many structures are already known (see PDB) and one can match sequences directly with structures to enhance structure recognition: fold recognition (not for new folds!) l For both, fold recognition and de novo simulation, prediction of intermediate attributes such secondary structure or solvent accessibility helps to achieve better sensitivity and specificity l JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 11

Why “fold recognition”? l Divergent (common ancestor) vs. convergent (no ancestor) evolution l PDB: virtually all proteins with 30% seq. identity have similar structures, however most of the similar structures share only up to 10% of seq. identity ! JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 12

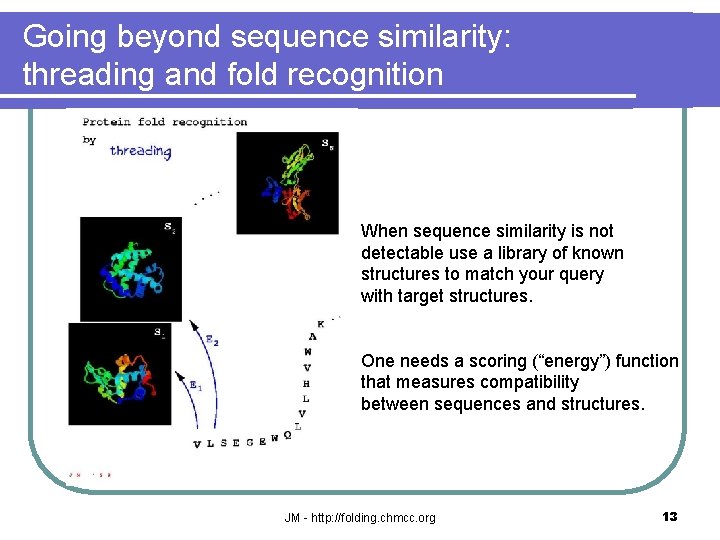

Going beyond sequence similarity: threading and fold recognition When sequence similarity is not detectable use a library of known structures to match your query with target structures. One needs a scoring (“energy”) function that measures compatibility between sequences and structures. JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 13

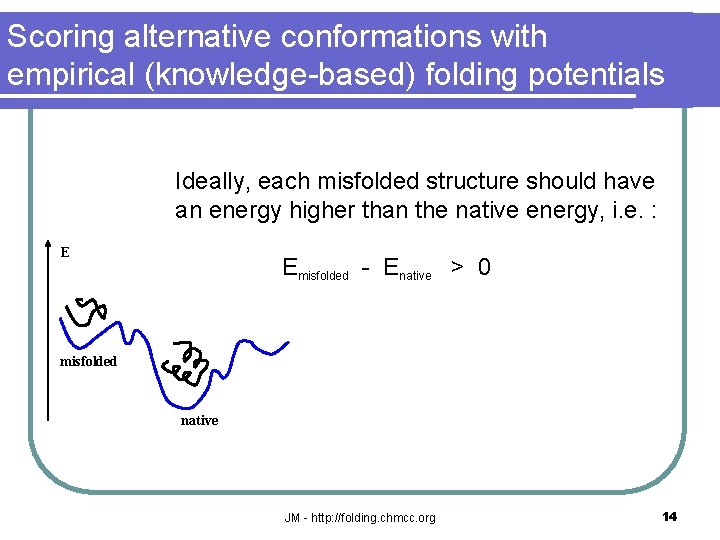

Scoring alternative conformations with empirical (knowledge-based) folding potentials Ideally, each misfolded structure should have an energy higher than the native energy, i. e. : E Emisfolded - Enative > 0 misfolded native JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 14

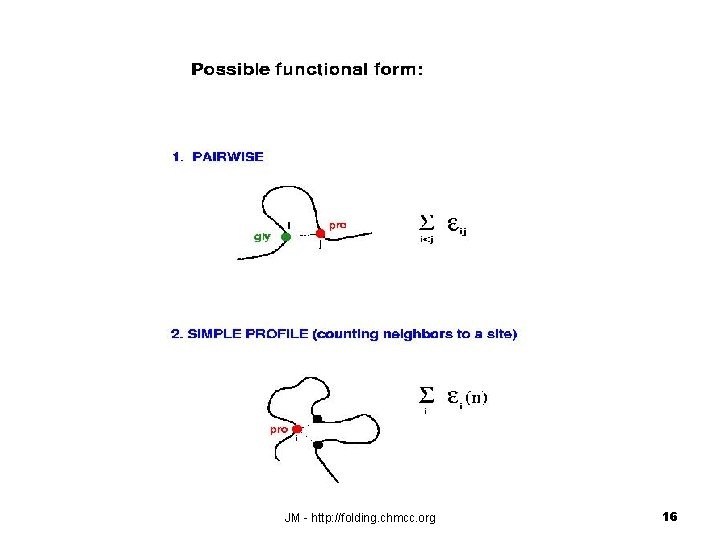

Simple contact model for protein structure prediction Each amino acid is represented by a point in 3 D space and two amino acids are said to be in contact if their distance is smaller than a cutoff distance, e. g. 7 [Ang]. JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 15

JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 16

JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 17

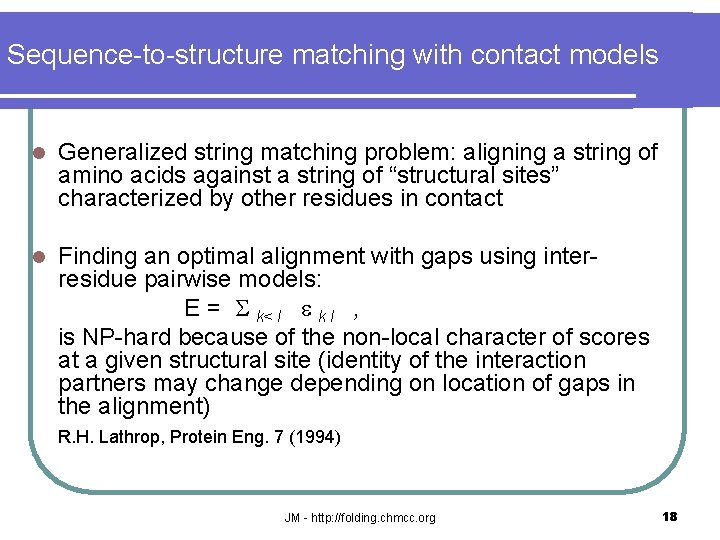

Sequence-to-structure matching with contact models l Generalized string matching problem: aligning a string of amino acids against a string of “structural sites” characterized by other residues in contact l Finding an optimal alignment with gaps using interresidue pairwise models: E = S k< l e k l , is NP-hard because of the non-local character of scores at a given structural site (identity of the interaction partners may change depending on location of gaps in the alignment) R. H. Lathrop, Protein Eng. 7 (1994) JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 18

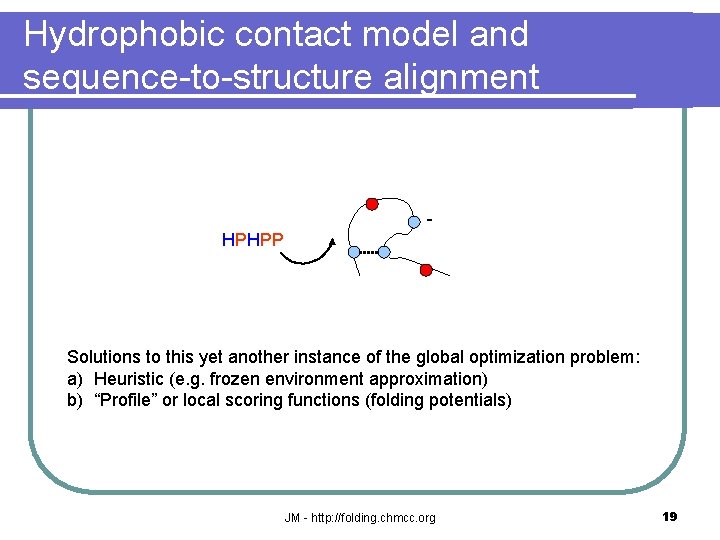

Hydrophobic contact model and sequence-to-structure alignment HPHPP Solutions to this yet another instance of the global optimization problem: a) Heuristic (e. g. frozen environment approximation) b) “Profile” or local scoring functions (folding potentials) JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 19

Implementing threading protocols: LOOPP in CAFASP 4 • About average for all fold recognition targets (missing some easy targets, recognized by Psi. Blast) • Third best server in the category of difficult targets • Best predictions among the servers for 3 difficult targets • Further improvements necessary to make the predictions more robust Joint work with Ron Elber JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 20

Using sequence similarity, predicted secondary structures and contact potentials: fold recognition protocols In practice fold recognition methods are often mixtures of sequence matching and threading, with compatibility between a sequence and a structure measured by: i) sequence alignment ii) contact potentials iii) predicted secondary structures (compared to the secondary structure of a template) JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 21

Predicting 1 D protein profiles from sequences: secondary structures and solvent accessibility a) Multiple alignment and family profiles improve prediction of local structural propensities b) Use of advanced machine learning techniques, such as Neural Networks or Support Vector Machines improves results as well B. Rost and C. Sander were first to achieve more than 70% accuracy in three state (H, E, C) classification, applying a) and b). SABLE server http: //sable. cchmc. org POLYVIEW server http: //polyview. cchmc. org JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 22

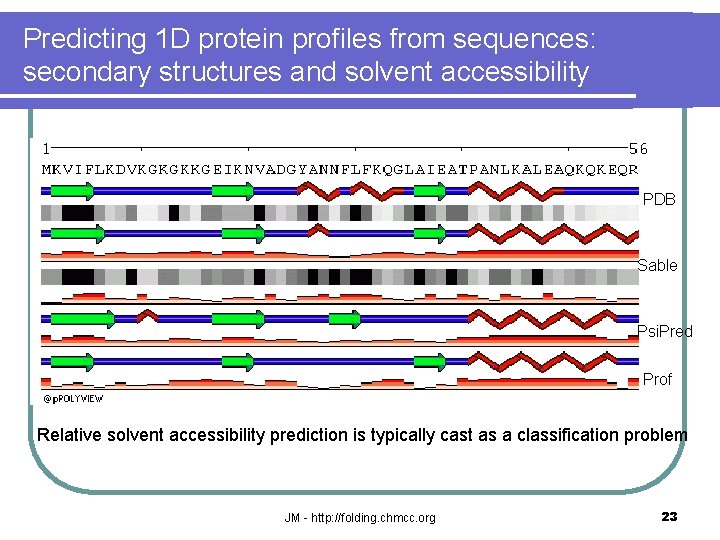

Predicting 1 D protein profiles from sequences: secondary structures and solvent accessibility PDB Sable Psi. Pred Prof Relative solvent accessibility prediction is typically cast as a classification problem JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 23

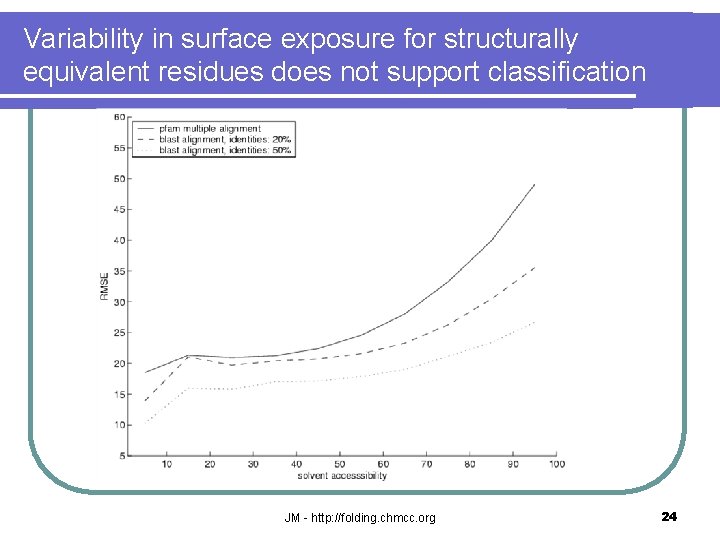

Variability in surface exposure for structurally equivalent residues does not support classification JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 24

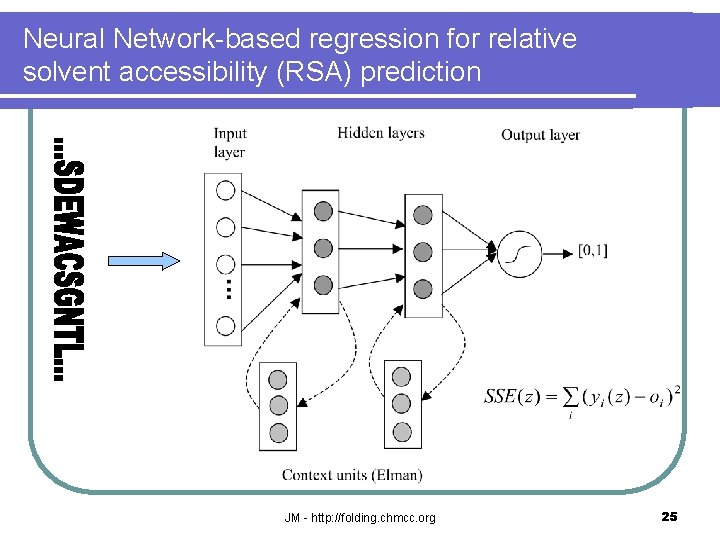

Neural Network-based regression for relative solvent accessibility (RSA) prediction JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 25

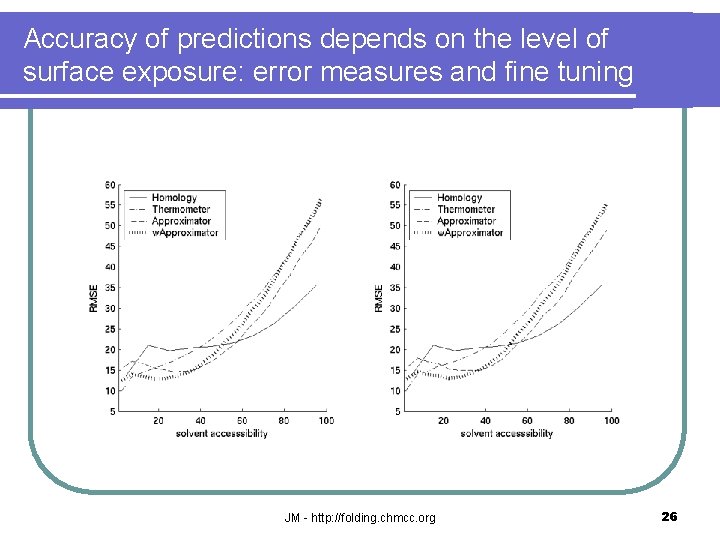

Accuracy of predictions depends on the level of surface exposure: error measures and fine tuning JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 26

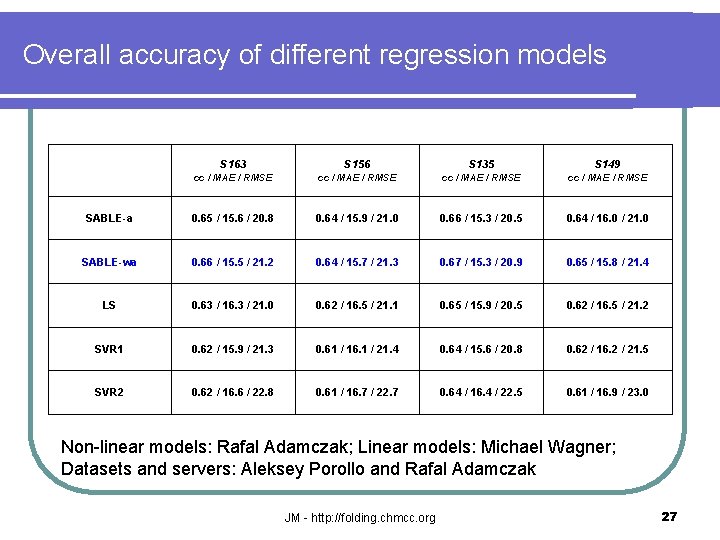

Overall accuracy of different regression models S 163 S 156 S 135 S 149 cc / MAE / RMSE SABLE-a 0. 65 / 15. 6 / 20. 8 0. 64 / 15. 9 / 21. 0 0. 66 / 15. 3 / 20. 5 0. 64 / 16. 0 / 21. 0 SABLE-wa 0. 66 / 15. 5 / 21. 2 0. 64 / 15. 7 / 21. 3 0. 67 / 15. 3 / 20. 9 0. 65 / 15. 8 / 21. 4 LS 0. 63 / 16. 3 / 21. 0 0. 62 / 16. 5 / 21. 1 0. 65 / 15. 9 / 20. 5 0. 62 / 16. 5 / 21. 2 SVR 1 0. 62 / 15. 9 / 21. 3 0. 61 / 16. 1 / 21. 4 0. 64 / 15. 6 / 20. 8 0. 62 / 16. 2 / 21. 5 SVR 2 0. 62 / 16. 6 / 22. 8 0. 61 / 16. 7 / 22. 7 0. 64 / 16. 4 / 22. 5 0. 61 / 16. 9 / 23. 0 Non-linear models: Rafal Adamczak; Linear models: Michael Wagner; Datasets and servers: Aleksey Porollo and Rafal Adamczak JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 27

Regression vs. two-classification Method S 163 S 156 S 135 S 149 ACCpro server 25% 70. 4% / 0. 41 69. 8% / 0. 41 70. 6% / 0. 42 71. 1% / 0. 43 SABLE-wa BS 62 71. 7% / 0. 43 71. 1% / 0. 42 72. 2% / 0. 44 SABLE-wa binary 71. 4% / 0. 42 70. 9% / 0. 41 71. 9% / 0. 43 72. 1% / 0. 44 SABLE-2 c 25% 76. 7% / 0. 53 75. 8% / 0. 52 77. 1% / 0. 54 76. 4% / 0. 53 SABLE-wa 77. 3% / 0. 54 76. 5% / 0. 52 77. 3% / 0. 54 76. 6% / 0. 53 JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 28

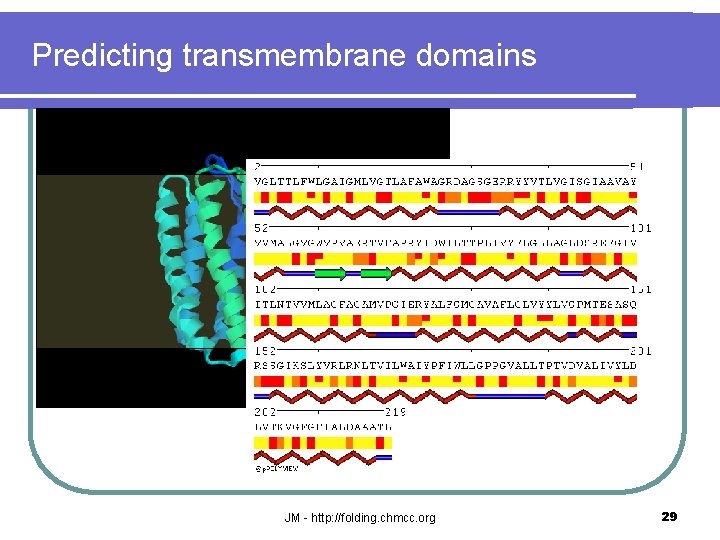

Predicting transmembrane domains JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 29

Predicting transmembrane domains JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 30

Now back to threading and folding simulations Applications in filtering out incorrect models in both de novo simulations and fold recognition l Domain structure prediction, protein-protein interactions l Better sensitivity in finding correct matches in threading: one story as an example l JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 31

Modeling the RNA Polymerase II Interaction with the von Hippel-Lindau Protein: Protein from experimental clues to structure prediction and back to experiment. Jarek Meller Children’s Hospital Research Foundation Joint work with M. Czyzyk-Krzeska and her group, College of Medicine, University of Cincinnati JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 32

A play of life (script and beyond): n n Stage: protein society or proteosome Rules of life: proteins are assembled and degraded: nursery (ribosome) vs. police and gillotine (ubiquitination and proteasome) n Social order: one look at the equilibrium in the system: Transcription Army of scribers (middle class proteins) Translation Law and oppression Holy scriptures (DNA) Temple priests (selected proteins) “I think we need to adjust the interpretation of the script … “ (regulation of replication and transcription) JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 33

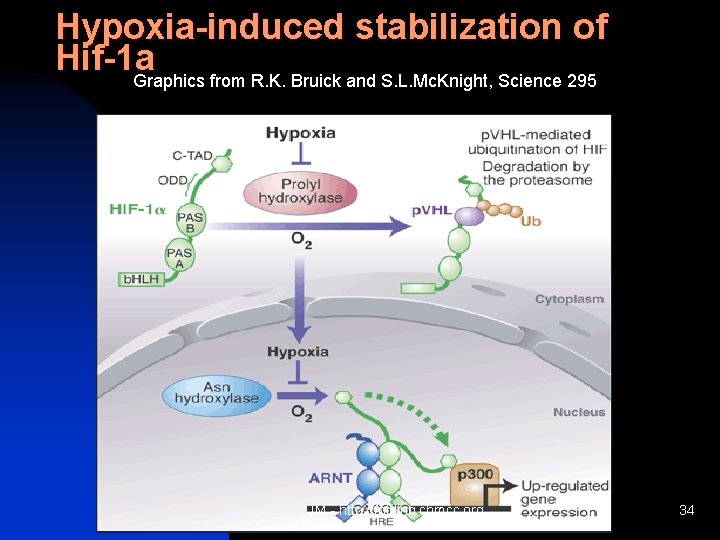

Hypoxia-induced stabilization of Hif-1 a Graphics from R. K. Bruick and S. L. Mc. Knight, Science 295 JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 34

Experimental clues: q q q Observation: correlation between p. VHL levels and transcript elongation of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene (M. Czyzyk-Krzeska) Could p. VHL influence the transcription by interaction with elongation complex co-factors ? Where to start? Experiment without a model is usually not a very good idea. Could in silico study and bioinformatics help? JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 35

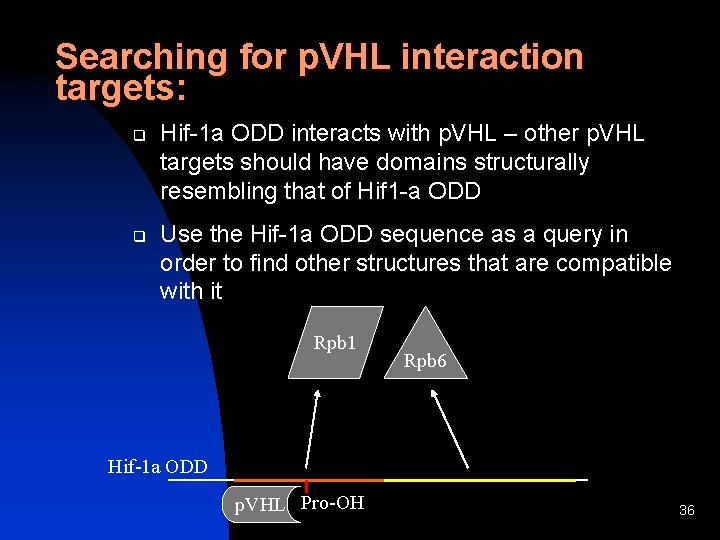

Searching for p. VHL interaction targets: q q Hif-1 a ODD interacts with p. VHL – other p. VHL targets should have domains structurally resembling that of Hif 1 -a ODD Use the Hif-1 a ODD sequence as a query in order to find other structures that are compatible with it Rpb 1 Rpb 6 Hif-1 a ODD p. VHL Pro-OH 36

RNA Polymerase II in the act of transcription, Gnatt, Kornberg et. al. , Science 292 (2001) JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 37

The C-terminal of Rpb 1 and Rpb 6 form a pocket on the surface of RNA Polymerase II complex. C-ter of Rpb 1 and Rpb 6 represented by cartoons. C-ter Rpb 1 Rpb 6 JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 38

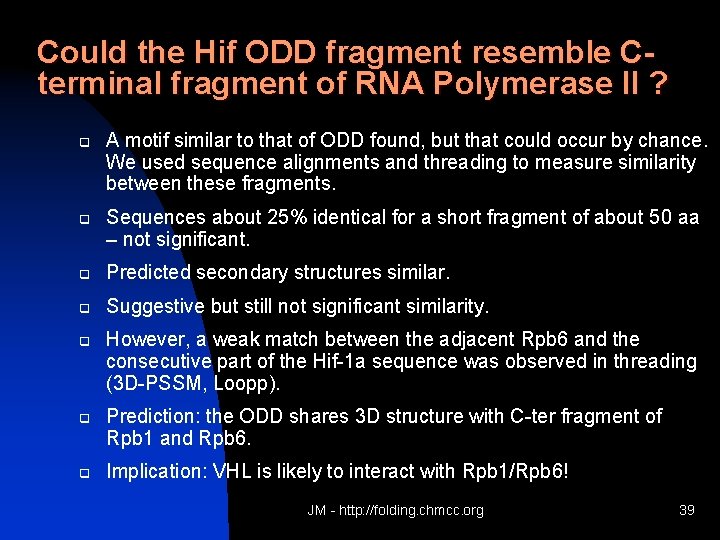

Could the Hif ODD fragment resemble Cterminal fragment of RNA Polymerase II ? q q A motif similar to that of ODD found, but that could occur by chance. We used sequence alignments and threading to measure similarity between these fragments. Sequences about 25% identical for a short fragment of about 50 aa – not significant. q Predicted secondary structures similar. q Suggestive but still not significant similarity. q q q However, a weak match between the adjacent Rpb 6 and the consecutive part of the Hif-1 a sequence was observed in threading (3 D-PSSM, Loopp). Prediction: the ODD shares 3 D structure with C-ter fragment of Rpb 1 and Rpb 6. Implication: VHL is likely to interact with Rpb 1/Rpb 6! JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 39

Experimental results (MCK): n n RNA Pol II peptides suggested by computational analysis do bind to p. VHL and this binding is controlled by hydroxylation of the critical PRO residue. Co-immunoprecipitations of hyperphosphorylated RNA Pol II and p. VHL observed: interaction confirmed. Ubiquitination of Rpb 1 confirmed. Biological meaning? JM - http: //folding. chmcc. org 40

- Slides: 40