Key Variables Social Science Measurement and Functional Form

Key Variables: Social Science Measurement and Functional Form Presentation to: ‘Interpreting results from statistical modelling – A seminar for Scottish Government Social Researchers”, Edinburgh, 1 April 2009 Dr Paul Lambert and Professor Vernon Gayle University of Stirling Key variables 1

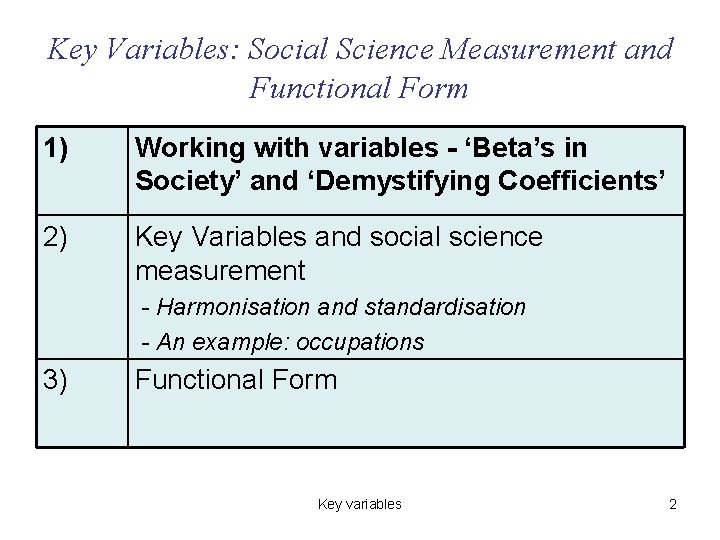

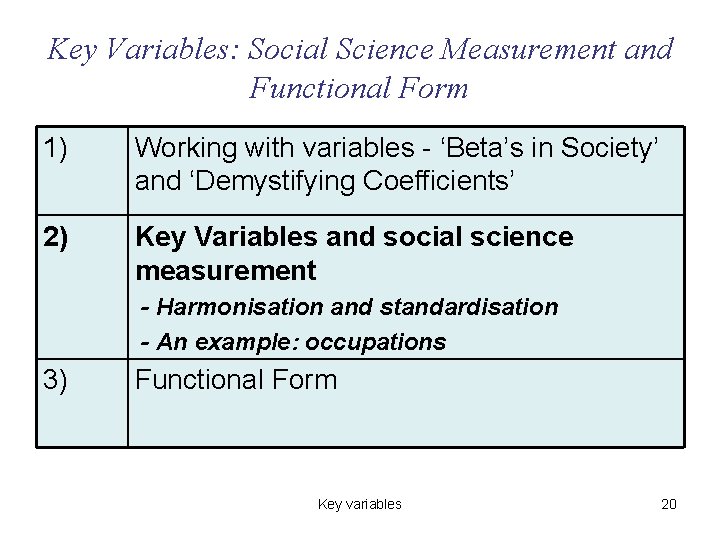

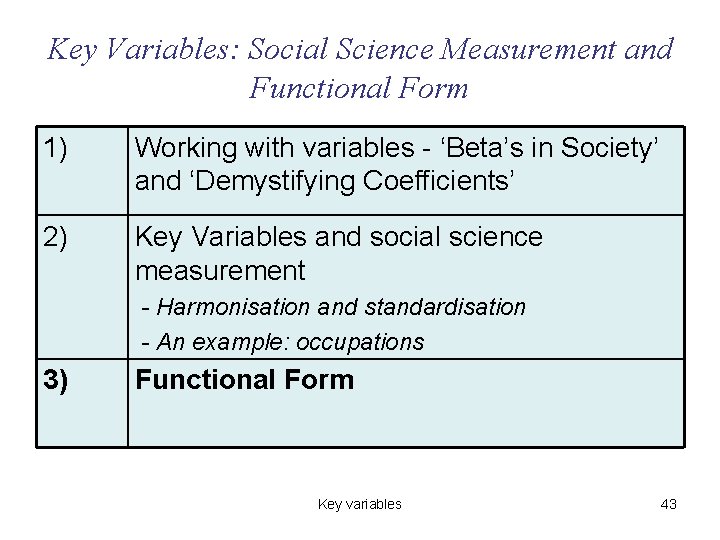

Key Variables: Social Science Measurement and Functional Form 1) Working with variables - ‘Beta’s in Society’ and ‘Demystifying Coefficients’ 2) Key Variables and social science measurement - Harmonisation and standardisation - An example: occupations 3) Functional Form Key variables 2

‘Beta’s in Society’ and ‘Demystifying Coefficients’ Ø Dorling, D. , & Simpson, S. (Eds. ). (1999). Statistics in Society: The Arithmetic of Politics. London: Arnold. Ø Irvine, J. , Miles, I. , & Evans, J. (Eds. ). (1979). Demystifying Social Statistics. London: Pluto Press. • Famous works on critical interpretation of social statistics tend to have a univariate / bivariate focus – Measuring unemployment; averaging income; bivariate significance tests; correlation v’s causation • But social survey analysts usually argue that complex multivariate analyses are more appropriate. . Ø Critical interpretation of joint relative effects Ø Attention to effects of ‘key variables’ in multivariate analysis Key variables 3

• “A program like SPSS. . has two main components: the statistical routines, . . and the data management facilities. Perhaps surprisingly, it was the latter that really revolutionised quantitative social research” [Procter, 2001: 253] • “Socio-economic processes require comprehensive approaches as they are very complex (‘everything depends on everything else’). The data and computing power needed to disentangle the multiple mechanisms at work have only just become available. ” [Crouchley and Fligelstone 2004] Key variables 4

Large scale survey data: 2 technological themes • We’re data rich (but analysts’ poor) • Plenty of variables (a thousand is common) • Plenty of cases • We work overwhelmingly through individual analysts’ micro-computing – impact of mainstream software – Pressure for simple / accessible / popular analytical techniques (whatever happened to loglinear models? ) – Propensity for simple ‘data management’ – Specialist development of very complex analytical packages for very simple sets of variables Key variables 5

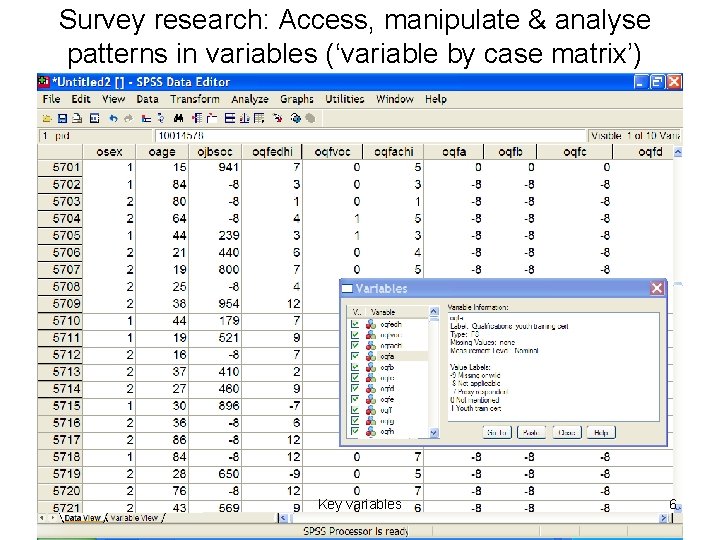

Survey research: Access, manipulate & analyse patterns in variables (‘variable by case matrix’) Key variables 6

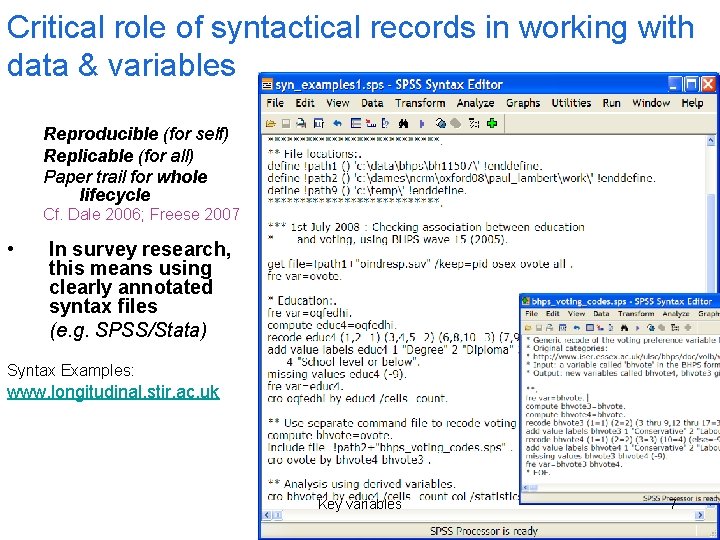

Critical role of syntactical records in working with data & variables Reproducible (for self) Replicable (for all) Paper trail for whole lifecycle Cf. Dale 2006; Freese 2007 • In survey research, this means using clearly annotated syntax files (e. g. SPSS/Stata) Syntax Examples: www. longitudinal. stir. ac. uk Key variables 7

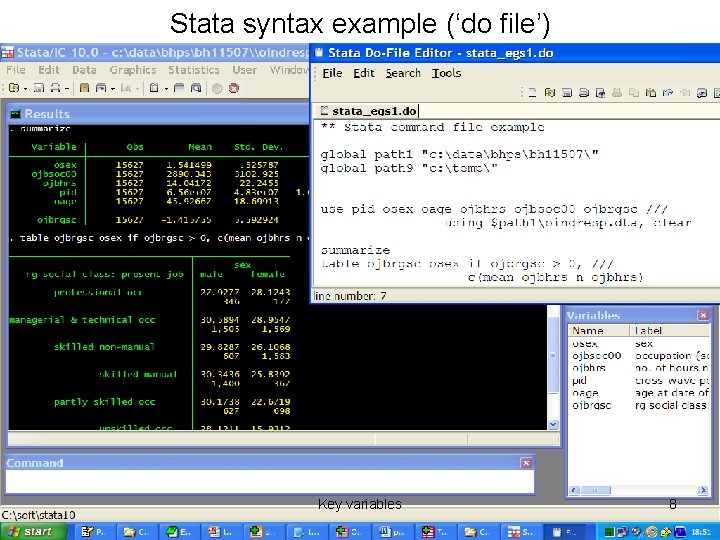

Stata syntax example (‘do file’) Key variables 8

Some comments on survey analysis software for analysing variables. . • Data management and data analysis must be seen as integrated processes • Stata is the most effective software, as it combines advanced data management and data analysis functionality and makes good documentation easy • For an extended example of using Stata, concentrating on variable operationalisations and standardisations: – Lambert, P. S. , & Gayle, V. (2009). Data management and standardisation: A methodological comment on using results from the UK Research Assessment Exercise 2008. Stirling: University of Stirling, Technical paper 2008 -3 of the Data Management through e-Social Science research Node (www. dames. org. uk) E. g. “do http: //www. dames. org. uk/rae 2008/uoa 0108 recode. do” E. g. “use http: //www. dames. org. uk/rae 2008_3. dta, clear” Key variables 9

Working with variables and understanding ‘variable constructions’ processes by which survey measures are defined and subsequently interpreted by research analysts • Meaning? – Coding frames; re-coding decisions; metric transformations and functional forms; relative effects in multivariate models – Data collection and data analysis – Cf. www. longitudinal. stir. ac. uk/variables/ Key variables 10

β’s - Where’s the action? • If we have lots of variables, lots of cases, yet often quite simple techniques and software, the action is primarily in the variable constructions… • The example of social mobility research – see Lambert et al. (2007) i. How we chose between alternative measures ii. How much data management we try (or bother with) Plus other issues in how we analyse & interpret the coefficients from the models we use (. . elsewhere today. . ) Key variables 11

i) Choosing measures See (2) below • A sensible starting point is with ‘key variables’ • Approaches to standardisation / harmonisation • {Lack of} awareness of existing resources See (3) below • Influence of functional form Key variables 12

ii) Data management – e. g. recoding data Key variables 13

ii) Data management – e. g. Missing data / case selection Key variables 14

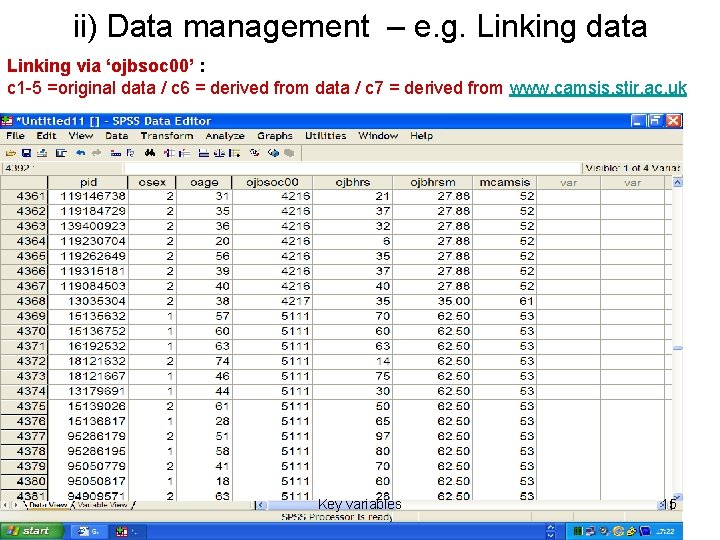

ii) Data management – e. g. Linking data Linking via ‘ojbsoc 00’ : c 1 -5 =original data / c 6 = derived from data / c 7 = derived from www. camsis. stir. ac. uk Key variables 15

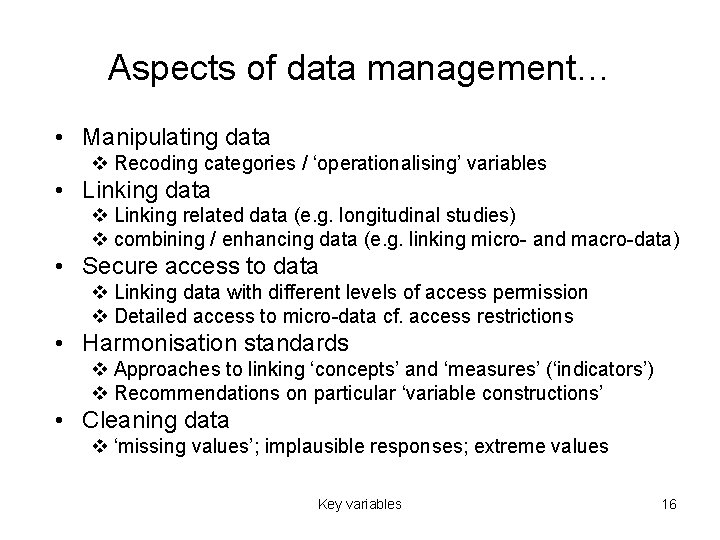

Aspects of data management… • Manipulating data v Recoding categories / ‘operationalising’ variables • Linking data v Linking related data (e. g. longitudinal studies) v combining / enhancing data (e. g. linking micro- and macro-data) • Secure access to data v Linking data with different levels of access permission v Detailed access to micro-data cf. access restrictions • Harmonisation standards v Approaches to linking ‘concepts’ and ‘measures’ (‘indicators’) v Recommendations on particular ‘variable constructions’ • Cleaning data v ‘missing values’; implausible responses; extreme values Key variables 16

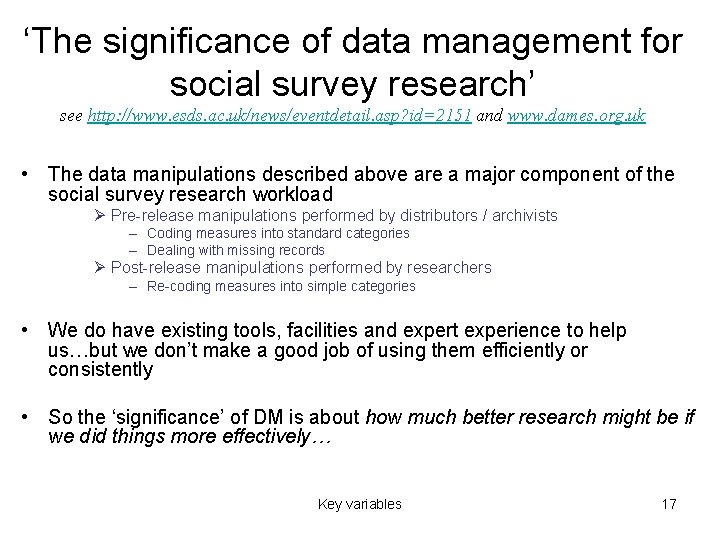

‘The significance of data management for social survey research’ see http: //www. esds. ac. uk/news/eventdetail. asp? id=2151 and www. dames. org. uk • The data manipulations described above are a major component of the social survey research workload Ø Pre-release manipulations performed by distributors / archivists – Coding measures into standard categories – Dealing with missing records Ø Post-release manipulations performed by researchers – Re-coding measures into simple categories • We do have existing tools, facilities and expert experience to help us…but we don’t make a good job of using them efficiently or consistently • So the ‘significance’ of DM is about how much better research might be if we did things more effectively… Key variables 17

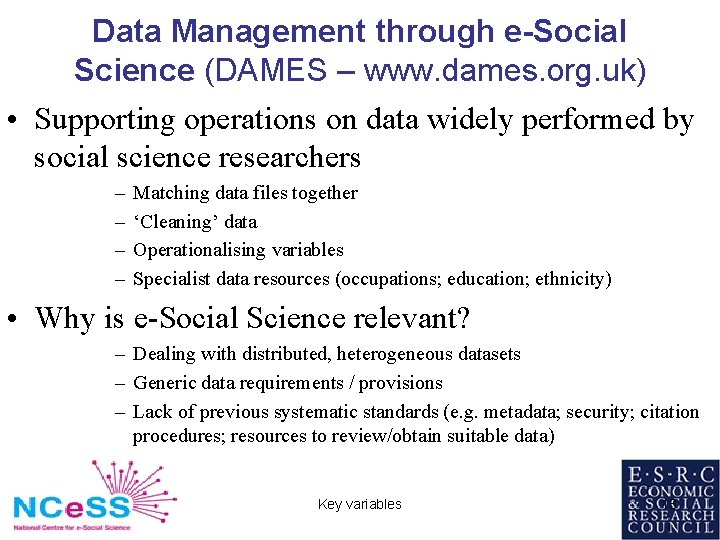

Data Management through e-Social Science (DAMES – www. dames. org. uk) • Supporting operations on data widely performed by social science researchers – – Matching data files together ‘Cleaning’ data Operationalising variables Specialist data resources (occupations; education; ethnicity) • Why is e-Social Science relevant? – Dealing with distributed, heterogeneous datasets – Generic data requirements / provisions – Lack of previous systematic standards (e. g. metadata; security; citation procedures; resources to review/obtain suitable data) Key variables 18

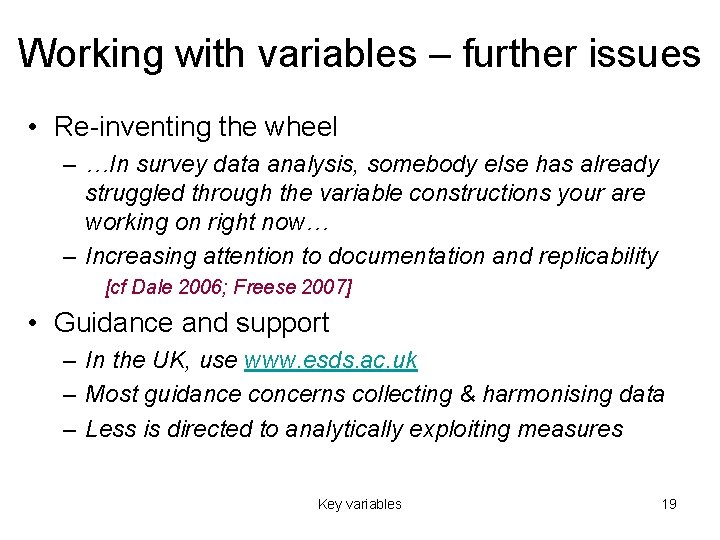

Working with variables – further issues • Re-inventing the wheel – …In survey data analysis, somebody else has already struggled through the variable constructions your are working on right now… – Increasing attention to documentation and replicability [cf Dale 2006; Freese 2007] • Guidance and support – In the UK, use www. esds. ac. uk – Most guidance concerns collecting & harmonising data – Less is directed to analytically exploiting measures Key variables 19

Key Variables: Social Science Measurement and Functional Form 1) Working with variables - ‘Beta’s in Society’ and ‘Demystifying Coefficients’ 2) Key Variables and social science measurement - Harmonisation and standardisation - An example: occupations 3) Functional Form Key variables 20

Key variables and social science measurement Defining ‘key variables’ - Commonly used concepts with numerous previous examples - Methodological research on best practice / best measurement [cf. Stacey 1969; Burgess 1986] ONS harmonisation ‘primary standards’ http: //www. statistics. gov. uk/about/data/harmonisation/primary_standards. asp Key variables 21

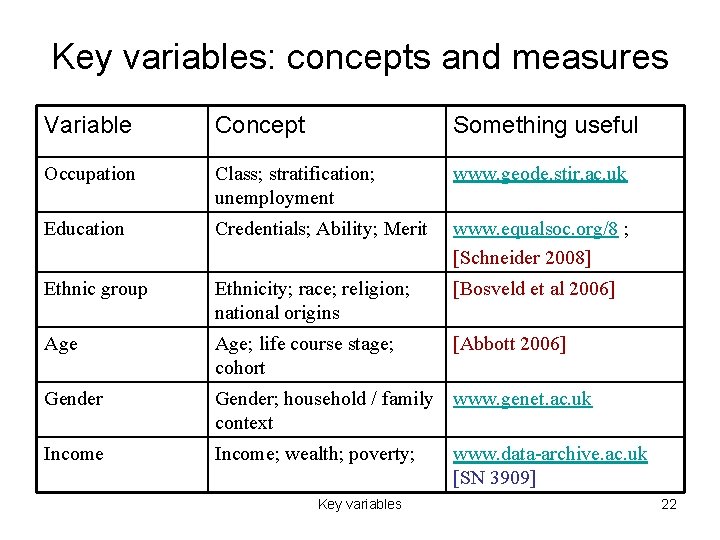

Key variables: concepts and measures Variable Concept Something useful Occupation Class; stratification; unemployment www. geode. stir. ac. uk Education Credentials; Ability; Merit www. equalsoc. org/8 ; [Schneider 2008] Ethnic group Ethnicity; race; religion; national origins [Bosveld et al 2006] Age; life course stage; cohort [Abbott 2006] Gender; household / family www. genet. ac. uk context Income; wealth; poverty; Key variables www. data-archive. ac. uk [SN 3909] 22

Key variables –Standardisation • Much attention to key variables involves proposing optimum / standard measures • UK – ONS Harmonisation • EU – Eurostat standards • Studies of ‘criterion’ and ‘construct’ validity • Standardisation impacts other analyses – Affects available data – Affects popular interpretations of data Key variables 23

Key variables – Harmonisation (across countries; across time periods) • “a method for equating conceptually similar but operationally different variables. . ” [Harkness et al 2003, p 352] • Input harmonisation [esp. Harkness et al 2003] ‘harmonising measurement instruments’ [H-Z and Wolf 2003, p 394] – unlikely / impossible in longer-term longitudinal studies – common in small cross-national and short term lngtl. studies • Output harmonisation (‘ex-post harmonisation’) ‘harmonising measurement products’ [H-Z and Wolf 2003, p 394] Key variables 24

![More on harmonisation [esp. HZ and Wolf 2003, p 393 ff] • Numerous practical More on harmonisation [esp. HZ and Wolf 2003, p 393 ff] • Numerous practical](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/ad28be6c1928e7c135b66384e35cc9b5/image-25.jpg)

More on harmonisation [esp. HZ and Wolf 2003, p 393 ff] • Numerous practical resources to help with input and output harmonisation – [e. g. ONS www. statistics. gov. uk/about/data/harmonisation ; UN / EU / NSI’s; LIS project www. lisproject. org; IPUMS www. ipums. org ] – [Cross-national e. g. : HZ & Wolf 2003; Jowell et al. 2007] • Room for more work in justifying/ understanding interpretations after harmonisation Key variables 25

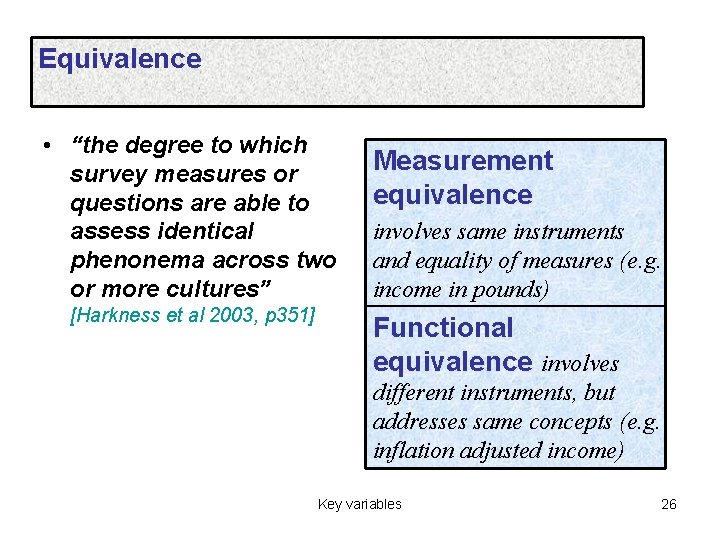

Equivalence • “the degree to which survey measures or questions are able to assess identical phenonema across two or more cultures” [Harkness et al 2003, p 351] Measurement equivalence involves same instruments and equality of measures (e. g. income in pounds) Functional equivalence involves different instruments, but addresses same concepts (e. g. inflation adjusted income) Key variables 26

“Equivalence is the only meaningful criterion if data is to be compared from one context to another. However, equivalence of measures does not necessarily mean that the measurement instruments used in different countries are all the same. Instead it is essential that they measure the same dimension. Thus, functional equivalence is more precisely what is required” [HZ and Wolf 2003, p 389] Key variables 27

Harmonisation & equivalence combined Ø‘Universality’ or ‘specificity’ in variable constructions Universality: collect harmonised measures, analyse standardised schemes Specificity: collect localised measures, analyse functionally equivalent schemes v. Most prescriptions aim for universality v. But specificity is theoretically better v. Specificity is more easily obtained than is often realised v. Especially for well-known ‘key variables’ Key variables 28

Working with key variables - speculation a) Data manipulation skills and inertia • I would speculate that around 80% of applications using key variables don’t consult literature and evaluate alternative measures, but choose the first convenient and/or accessible variable in the dataset Ø Data supply decisions (‘what is on the archive version’) are critical • Much of the explanation lies with lack of confidence in data manipulation / linking data • Too many under-used resources – cf. www. esds. ac. uk Key variables 29

Working with key variables – speculation b) Endogeneity and key variables • ‘everything depends on everything else’ [Crouchley and Fligelstone 2004] • We know a lot about simple properties of key variables • Key variables often change the main effects of other variables • Simple decisions about contrast categories can influence interpretations • Interaction terms are often significant and influential • We have only scratched the surface of understanding key variables in multivariate context and interpretation • Key variables are often endogenous (because they are ‘key’!) • Work on standards / techniques for multi-process systems and/or comparing structural breaks involving key variables is attractive Key variables 30

An example: Occupations • In the social sciences, occupation is seen as one of the most important things to know about a person Ø Direct indicator of economic circumstances Ø Proxy Indicator of ‘social class’ or ‘stratification’ • Projects at Stirling (www. dames. org. uk) • GEODE – how social scientists use data on occupations • DAMES – extending GEODE resources Key variables 31

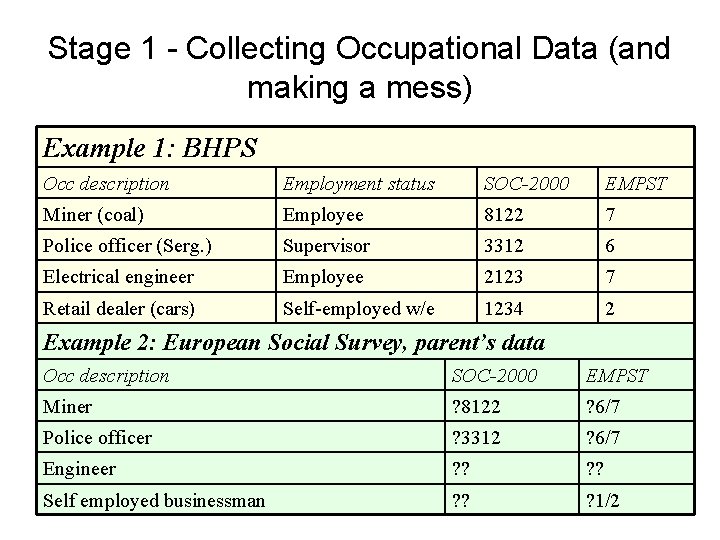

Stage 1 - Collecting Occupational Data (and making a mess) Example 1: BHPS Occ description Employment status SOC-2000 EMPST Miner (coal) Employee 8122 7 Police officer (Serg. ) Supervisor 3312 6 Electrical engineer Employee 2123 7 Retail dealer (cars) Self-employed w/e 1234 2 Example 2: European Social Survey, parent’s data Occ description SOC-2000 EMPST Miner ? 8122 ? 6/7 Police officer ? 3312 ? 6/7 Engineer ? ? Self employed businessman ? ? ? 1/2

www. geode. stir. ac. uk/ougs. html Key variables 33

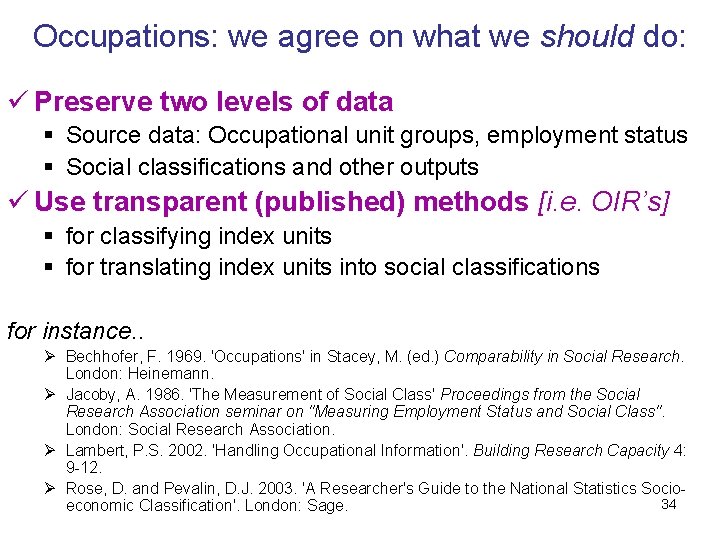

Occupations: we agree on what we should do: ü Preserve two levels of data § Source data: Occupational unit groups, employment status § Social classifications and other outputs ü Use transparent (published) methods [i. e. OIR’s] § for classifying index units § for translating index units into social classifications for instance. . Ø Bechhofer, F. 1969. 'Occupations' in Stacey, M. (ed. ) Comparability in Social Research. London: Heinemann. Ø Jacoby, A. 1986. 'The Measurement of Social Class' Proceedings from the Social Research Association seminar on "Measuring Employment Status and Social Class". London: Social Research Association. Ø Lambert, P. S. 2002. 'Handling Occupational Information'. Building Research Capacity 4: 9 -12. Ø Rose, D. and Pevalin, D. J. 2003. 'A Researcher's Guide to the National Statistics Socio 34 economic Classification'. London: Sage.

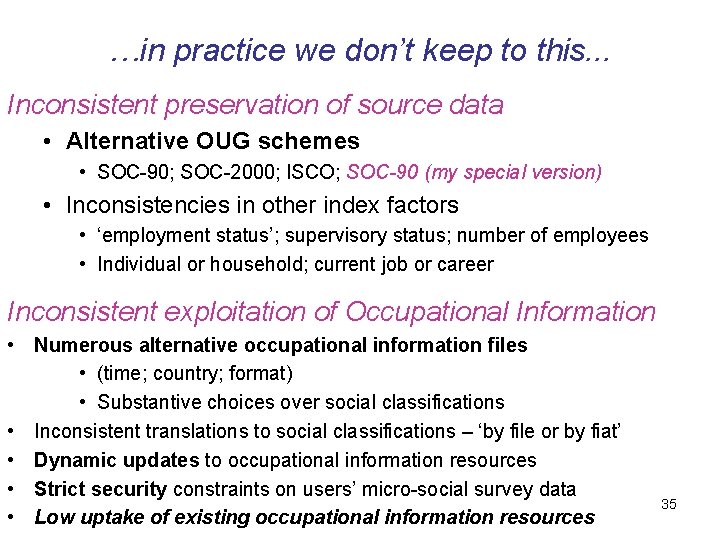

…in practice we don’t keep to this. . . Inconsistent preservation of source data • Alternative OUG schemes • SOC-90; SOC-2000; ISCO; SOC-90 (my special version) • Inconsistencies in other index factors • ‘employment status’; supervisory status; number of employees • Individual or household; current job or career Inconsistent exploitation of Occupational Information • Numerous alternative occupational information files • (time; country; format) • Substantive choices over social classifications • Inconsistent translations to social classifications – ‘by file or by fiat’ • Dynamic updates to occupational information resources • Strict security constraints on users’ micro-social survey data • Low uptake of existing occupational information resources 35

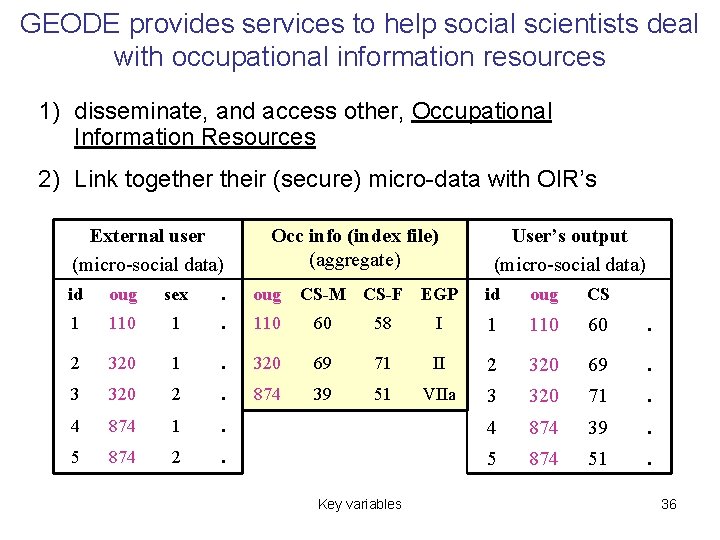

GEODE provides services to help social scientists deal with occupational information resources 1) disseminate, and access other, Occupational Information Resources 2) Link together their (secure) micro-data with OIR’s External user (micro-social data) Occ info (index file) (aggregate) id oug sex . oug CS-M CS-F EGP 1 110 1 . 110 60 58 2 320 1 . 320 69 3 320 2 . 874 39 4 874 1 5 874 2 User’s output (micro-social data) id oug CS I 1 110 60 . 71 II 2 320 69 . 51 VIIa 3 320 71 . . 4 874 39 . . 5 874 51 . Key variables 36

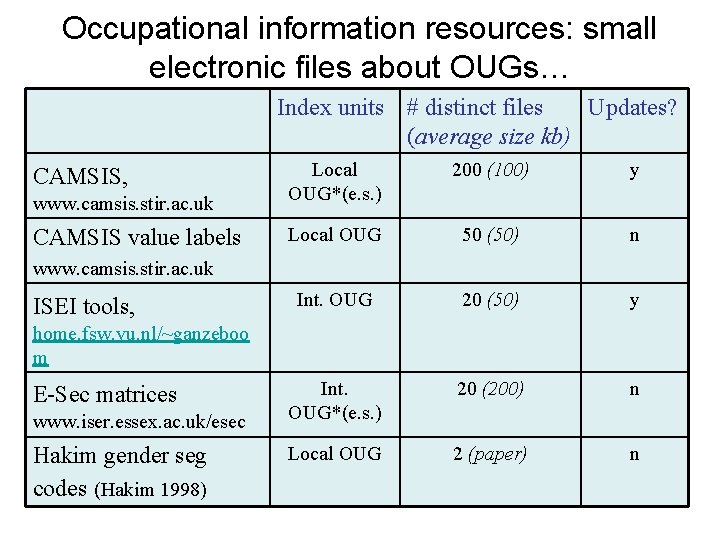

Occupational information resources: small electronic files about OUGs… Index units # distinct files Updates? (average size kb) 200 (100) y www. camsis. stir. ac. uk Local OUG*(e. s. ) CAMSIS value labels Local OUG 50 (50) n Int. OUG 20 (50) y Int. OUG*(e. s. ) 20 (200) n Local OUG 2 (paper) n CAMSIS, www. camsis. stir. ac. uk ISEI tools, home. fsw. vu. nl/~ganzeboo m E-Sec matrices www. iser. essex. ac. uk/esec Hakim gender seg codes (Hakim 1998)

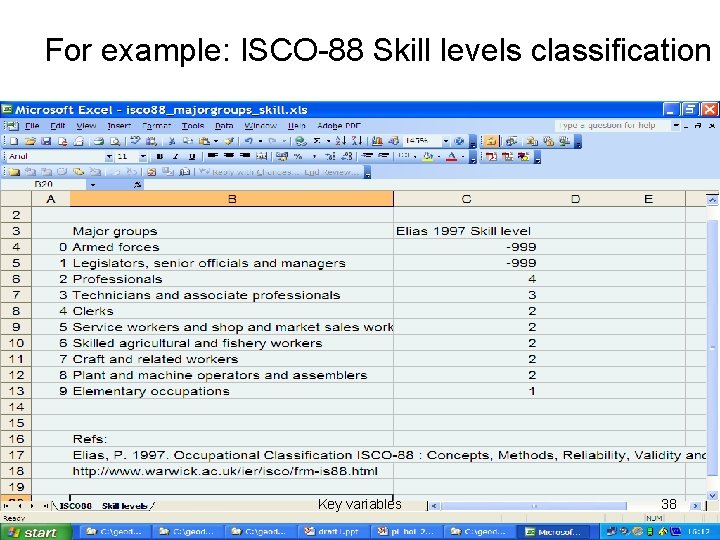

For example: ISCO-88 Skill levels classification Key variables 38

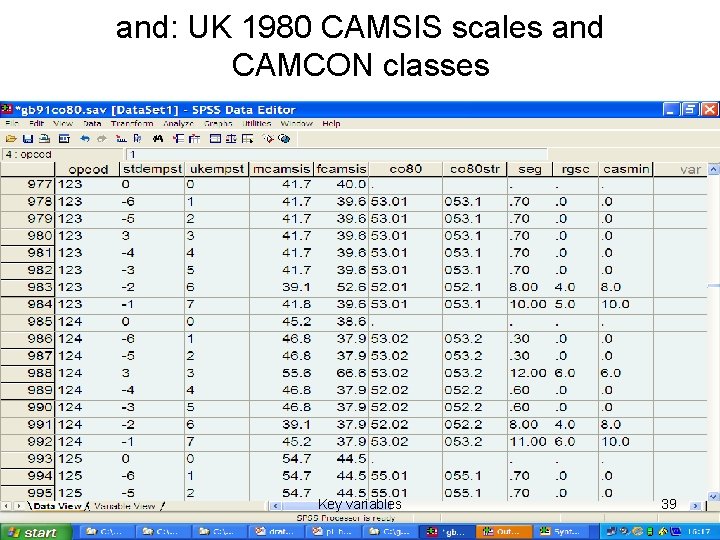

and: UK 1980 CAMSIS scales and CAMCON classes Key variables 39

Existing resources on occupations Popular websites: • http: //www 2. warwick. ac. uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/software/cascot/ • http: //home. fsw. vu. nl/~ganzeboom/pisa/ • www. iser. essex. ac. uk/esec/ • www. camsis. stir. ac. uk/occunits/distribution. html Emerging resource: http: //www. geode. stir. ac. uk/ Some papers: – Chan, T. W. , & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2007). Class and Status: The Conceptual Distinction and its Empirical Relevance. American Sociological Review, 72, 512532. – Rose, D. , & Harrison, E. (2007). The European Socio-economic Classification: A New Social Class Scheme for Comparative European Research. European Societies, 9(3), 459 -490. – Lambert, P. S. , Tan, K. L. L. , Gayle, V. , Prandy, K. , & Bergman, M. M. (2008). The importance of specificity in occupation-based social classifications. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 28(5/6), 179 -192. Key variables 40

Using data on occupations – further speculation • Growing interest in longitudinal analysis and use of longitudinal summary data on occupations • Intuitive measures (e. g. ever in Class I) Ø Lampard, R. (2007). Is Social Mobility an Echo of Educational Mobility? Sociological Research Online, 12(5). • Empirical career trajectories / sequences Ø Halpin, B. , & Chan, T. W. (1998). Class Careers as Sequences. European Sociological Review, 14(2), 111 -130. • Growing cross-national comparisons – Ganzeboom, H. B. G. (2005). On the Cost of Being Crude: A Comparison of Detailed and Coarse Occupational Coding. In J. H. P. Hoffmeyer-Zlotnick & J. Harkness (Eds. ), Methodological Aspects in Cross-National Research (pp. 241257). Mannheim: ZUMA, Nachrichten Spezial. • Treatment of the non-working populations • Seldom adequate to treat non-working as a category • ‘Selection modelling’ approaches expanding Key variables 41

Occupations as key variables • Extensive debate about occupation-based social classifications • Document your procedures. . • . . as you may be asked to do something different. . • When choosing between occupation-based measures… – They all measure, mostly, the same things – Don’t assume concepts measures • Lambert, P. S. , & Bihagen, E. (2007). Concepts and Measures: Empirical evidence on the interpretation of ESe. C and other occupation-based social classifications. Paper presented at the ISA RC 28 conference, Montreal (1417 August), www. camsis. stir. ac. uk/stratif/archive/lambert_bihagen_2007_version 1. pdf. Key variables 42

Key Variables: Social Science Measurement and Functional Form 1) Working with variables - ‘Beta’s in Society’ and ‘Demystifying Coefficients’ 2) Key Variables and social science measurement - Harmonisation and standardisation - An example: occupations 3) Functional Form Key variables 43

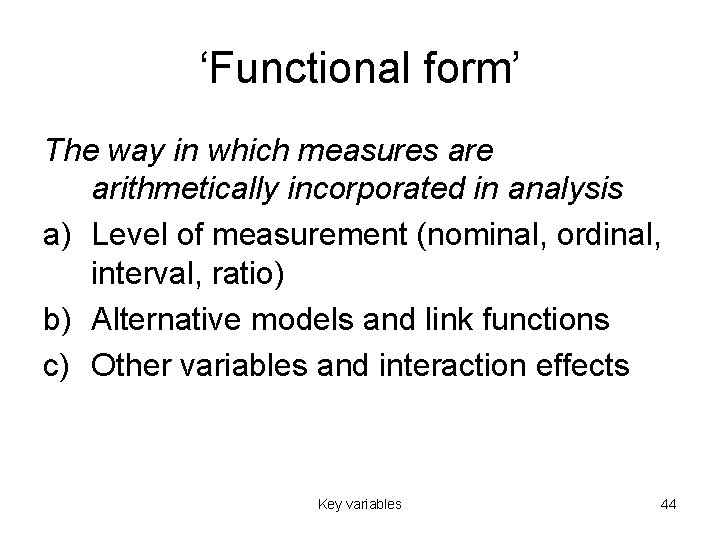

‘Functional form’ The way in which measures are arithmetically incorporated in analysis a) Level of measurement (nominal, ordinal, interval, ratio) b) Alternative models and link functions c) Other variables and interaction effects Key variables 44

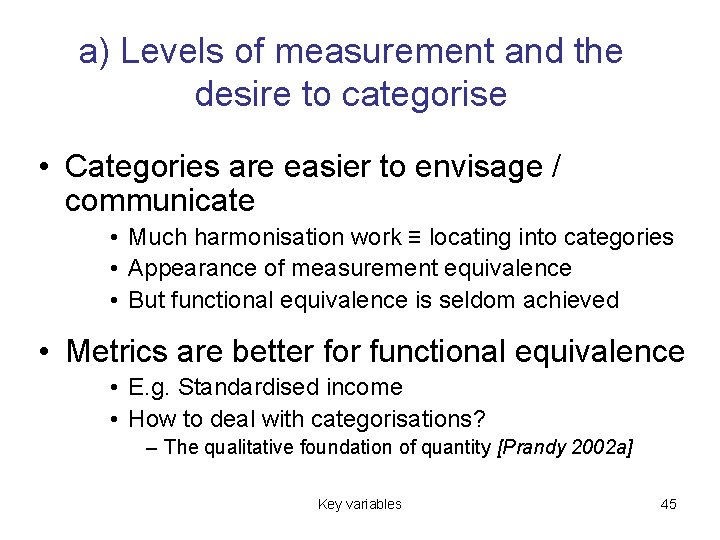

a) Levels of measurement and the desire to categorise • Categories are easier to envisage / communicate • Much harmonisation work ≡ locating into categories • Appearance of measurement equivalence • But functional equivalence is seldom achieved • Metrics are better for functional equivalence • E. g. Standardised income • How to deal with categorisations? – The qualitative foundation of quantity [Prandy 2002 a] Key variables 45

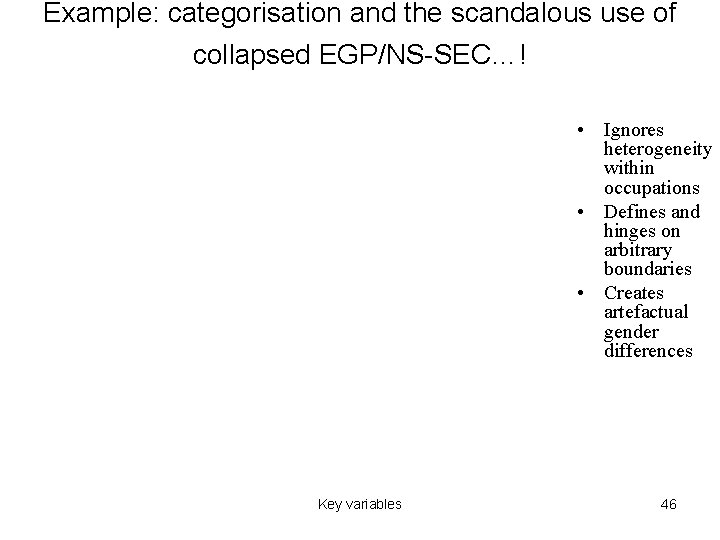

Example: categorisation and the scandalous use of collapsed EGP/NS-SEC…! • Ignores heterogeneity within occupations • Defines and hinges on arbitrary boundaries • Creates artefactual gender differences Key variables 46

The scaling alternative… • Many concepts can be reasonably regarded as metric – cf. simplified / dichotomisted categorisations • Comparability / standardisation is easier with scales • Complex / Multi-process systems are easier with scales – Structural Equation Models – Interaction effects • Growing availability/use of distance score techniques – Stereotyped ordered logit [‘slogit’ in Stata] – Correspondence Analysis – Latent variable models • …But, scaling seems to be seen by some as a wicked, positivistic activity. . ! Key variables 47

Practical suggestions on the level of measurement • It’s rare not to have a few alternative measures of the same concepts at different levels of measurement Good practice would be to – try alternative measures and see what difference they make – consider treatment of missing values in relation to measurement instrument choice – Engage as much as possible with other studies Key variables 48

b) Alternative models and link functions • The functional form of the outcome variable(s) is of greatest importance (influences which model is used) • ‘Link functions’ perform the maths to allow for alternative functional forms of the outcome variable • See [Talk 1] for popular alternative models Key variables 49

Practical observations on link functions • • Social scientists are unduly conservative in choosing between alternative models [We tend to favour binary or metric outcomes and single process systems] i. Substantively, this isn’t ideal ii. Pragmatically, it’s no longer necessary Key variables 50

Substantive risks (of conservative model choice) • Attenuated findings – Concentrate on certain category contrasts – Ignore or exacerbate extremes of distribution • Mis-specification – Ignore / mis-measure relevant β’s – Ignore / over-emphasise other contextual patterns • Endogeneity – ignoring multiprocess system may bias results (e. g. selection bias) Key variables 51

Pragmatics of model choice • General rapid expansion in model functionality in statistical packages • Stata stands out for it wide range of data management and data analysis functionality – E. g. ‘statsby’; ‘est table’; ‘outreg 2’; ‘estout’ facilitate testing and comparing related models with different combinations of variables Key variables 52

c) Other variables and interaction effects • A very important influence on one RHS coefficient is what else is in the RHS and what it is interacted with Some brief comments on: • Offsets (constraints) • Interactions • Logit models’ fixed variance Key variables 53

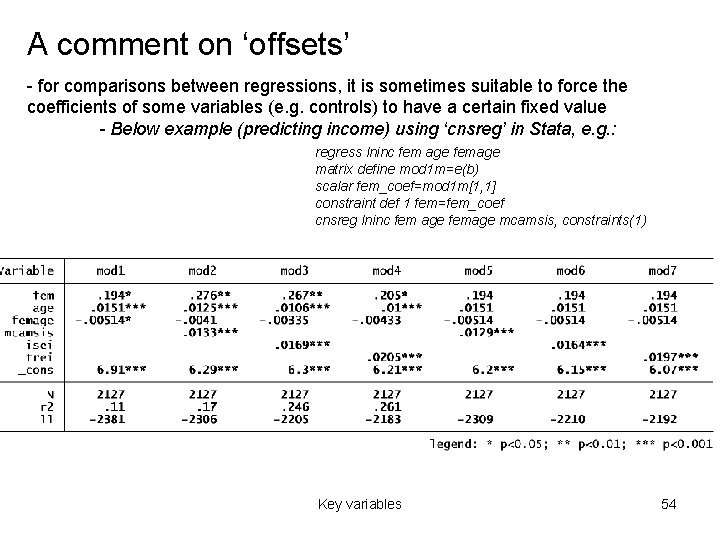

A comment on ‘offsets’ - for comparisons between regressions, it is sometimes suitable to force the coefficients of some variables (e. g. controls) to have a certain fixed value - Below example (predicting income) using ‘cnsreg’ in Stata, e. g. : regress lninc fem age femage matrix define mod 1 m=e(b) scalar fem_coef=mod 1 m[1, 1] constraint def 1 fem=fem_coef cnsreg lninc fem age femage mcamsis, constraints(1) Key variables 54

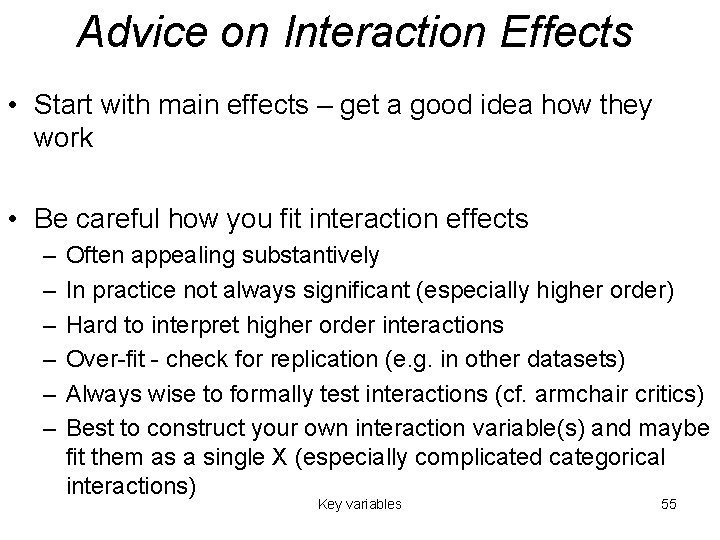

Advice on Interaction Effects • Start with main effects – get a good idea how they work • Be careful how you fit interaction effects – – – Often appealing substantively In practice not always significant (especially higher order) Hard to interpret higher order interactions Over-fit - check for replication (e. g. in other datasets) Always wise to formally test interactions (cf. armchair critics) Best to construct your own interaction variable(s) and maybe fit them as a single X (especially complicated categorical interactions) Key variables 55

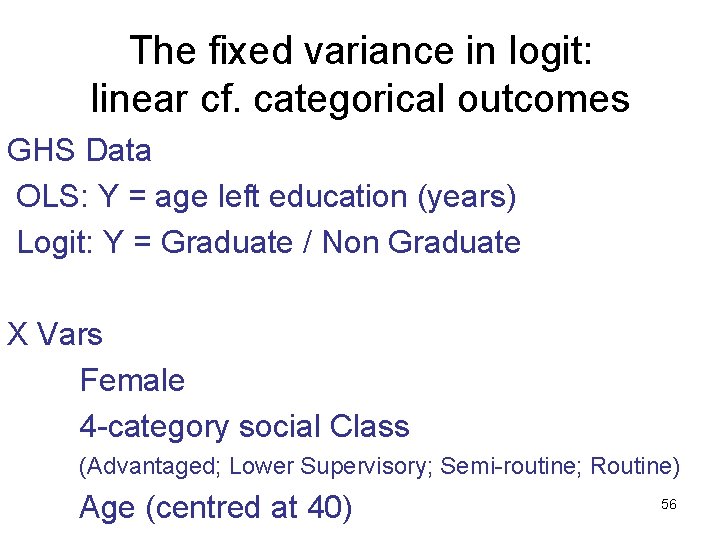

The fixed variance in logit: linear cf. categorical outcomes GHS Data OLS: Y = age left education (years) Logit: Y = Graduate / Non Graduate X Vars Female 4 -category social Class (Advantaged; Lower Supervisory; Semi-routine; Routine) Age (centred at 40) 56

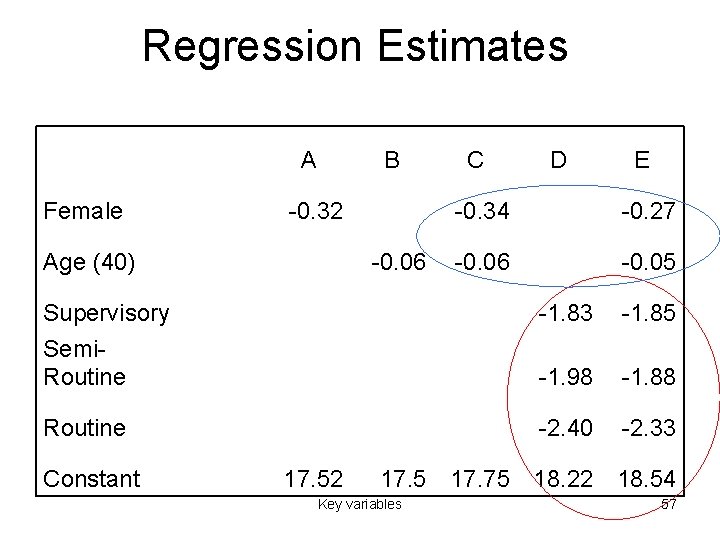

Regression Estimates A Female B -0. 32 Age (40) -0. 06 C D E -0. 34 -0. 27 -0. 06 -0. 05 Supervisory Semi. Routine -1. 83 -1. 85 -1. 98 -1. 88 Routine -2. 40 -2. 33 Constant 17. 52 17. 5 17. 75 18. 22 18. 54 Key variables 57

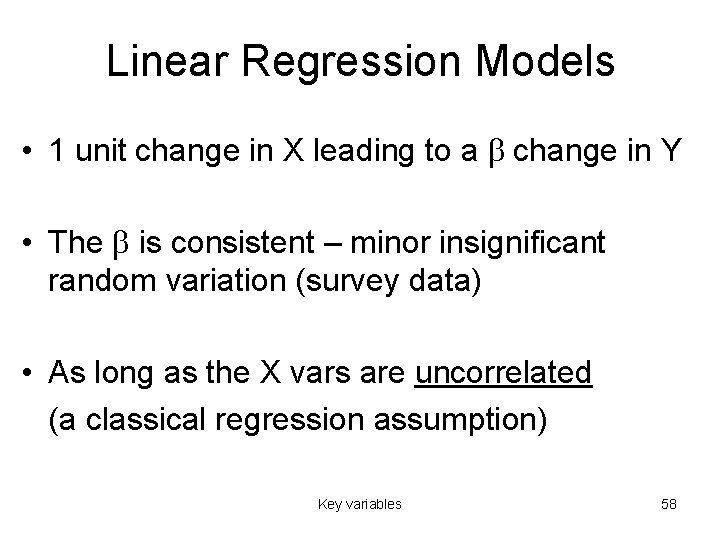

Linear Regression Models • 1 unit change in X leading to a b change in Y • The b is consistent – minor insignificant random variation (survey data) • As long as the X vars are uncorrelated (a classical regression assumption) Key variables 58

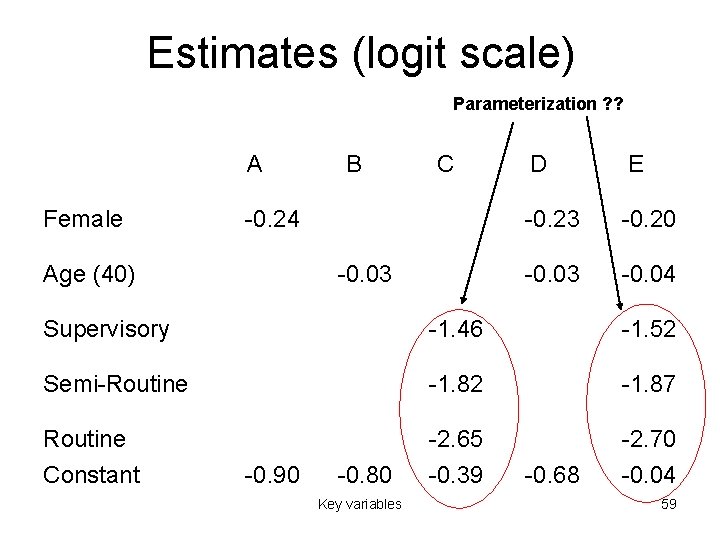

Estimates (logit scale) Parameterization ? ? A Female B C -0. 24 Age (40) -0. 03 D E -0. 23 -0. 20 -0. 03 -0. 04 Supervisory -1. 46 -1. 52 Semi-Routine -1. 82 -1. 87 Routine Constant -2. 65 -0. 39 -2. 70 -0. 04 -0. 90 -0. 80 Key variables -0. 68 59

Logit Model • Estimates on a logit scale • The b estimates a shift from X 1=0 to X 1=1 leads to a change in the log odds of y=1 • Even when the X vars are uncorrelated, including additional variables can lead to changes in b estimates • The b estimates the effect given all other X vars in the model • Fixed variance in the logit model (p 2/3) Key variables 60

Summary – Social science measurement and functional form • We argue that the route to better critical understanding of variable effects combines complex analysis with many mundane, prosaic tasks in checking data – ANALYSIS: Coefficient effects in multivariate models; multi-process models; understanding interactions; etc – DATA MANAGEMENT: Re-coding data; linking data; missing data mechanisms; reviewing literature • Seldom central to previous methodological reviews • Cf. www. dames. org. uk Key variables 61

References Ø Ø Ø Ø Abbott, A. (2006). Mobility: What? When? How? In S. L. Morgan, D. B. Grusky & G. S. Fields (Eds. ), Mobility and Inequality. Stanford University Press. Bosveld, K. , Connolly, H. , Rendall, M. S. , & (2006). A guide to comparing 1991 and 2001 Census ethnic group data. London: Office for National Statistics. Burgess, R. G. (Ed. ). (1986). Key Variables in Social Investigation. London: Routledge. Crouchley, R. , & Fligelstone, R. (2004). The Potential for High End Computing in the Social Sciences. Lancaster: Centre for Applied Statistics, Lancaster University, and http: //redress. lancs. ac. uk/document-pool/hecsspotential. pdf. Dale, A. (2006). Quality Issues with Survey Research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 9(2), 143 -158. Dorling, D. , & Simpson, S. (Eds. ). (1999). Statistics in Society: The Arithmetic of Politics. London: Arnold. Freese, J. (2007). Replication Standards for Quantitative Social Science: Why Not Sociology? Sociological Methods and Research, 36(2), 2007. Harkness, J. , van de Vijver, F. J. R. , & Mohler, P. P. (Eds. ). (2003). Cross-Cultural Survey Methods. New York: Wiley. Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J. H. P. , & Wolf, C. (Eds. ). (2003). Advances in Cross-national Comparison: A European Working Book for Demographic and Socio-economic Variables. Berlin: Kluwer Academic / Plenum Publishers. Irvine, J. , Miles, I. , & Evans, J. (Eds. ). (1979). Demystifying Social Statistics. London: Pluto Press. Jowell, R. , Roberts, C. , Fitzgerald, R. , & Eva, G. (2007). Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally. London: Sage. Lambert, P. S. , Prandy, K. , & Bottero, W. (2007). By Slow Degrees: Two Centuries of Social Reproduction and Mobility in Britain. Sociological Research Online, 12(1). Prandy, K. (2002). Measuring quantities: the qualitative foundation of quantity. Building Research Capacity, 2, 3 -4. Procter, M. (2001). Analysing Survey Data. In G. N. Gilbert (Ed. ), Researching Social Life, Second Edition (pp. 252268). London: Sage. Schneider, S. L. (2008). The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97). An Evaluation of Content and Criterion Validity for 15 European Countries. Mannheim: MZES. Stacey, M. (Ed. ). (1969). Comparability in Social Research. London: Heineman. 62

- Slides: 62