Jordans Principle Accountability Function Assembly of First Nations

Jordan’s Principle Accountability Function Assembly of First Nations Virtual Gathering on Jordan’s Principle: First Nations Innovation & Determination Presentation by: Naiomi Metallic & Shelby Thomas March 11, 2021

Context 2016 CHRT Caring Society Decision 1. Confirms Canada’s s 91(24) responsibility over First Nation child welfare 2. Confirms Jordan’s Principle as a human right 3. Finds that systems that perpetuate historic disadvantage / assimilation = discriminatory 4. Finds comparability = discriminatory • Substantive equality requires meeting “the distinct needs and circumstances … including cultural, historical and geographical needs and circumstances” of FN children and families.

Tribunal: • “… a REFORM of the FNCFS Program is needed in order to build a solid foundation for the program to address the real needs of First Nations children and families living on reserve. ”

![Jordan’s Principle – CHRT Rulings [351] Jordan’s Principle is a child-first principle and provides Jordan’s Principle – CHRT Rulings [351] Jordan’s Principle is a child-first principle and provides](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/1ec45c5b10b0ade9dcba77fdbff775d0/image-4.jpg)

Jordan’s Principle – CHRT Rulings [351] Jordan’s Principle is a child-first principle and provides that where a government service is available to all other children and a jurisdictional dispute arises between Canada and a province/territory, or between departments in the same government regarding services to a First Nations child, the government department of first contact pays for the service and can seek reimbursement from the other government/department after the child has received the service. It is meant to prevent First Nations children from being denied essential public services or experiencing delays in receiving them. [391] … where the FNCFS Program is complemented by other federal programs aimed at addressing the needs of children and families on reserve, there is also a lack of coordination between the different programs. The evidence indicates that federal government departments often work in silos. This practice results in service gaps, delays or denials and, overall, adverse impacts on First Nations children and families on reserves. Jordan’s Principle was meant to address this issue…

• Stop applying a narrow definition of Jordan’s Principle. • Apply Jordan’s Principle to all First Nations meeting any one of the following criteria: Jordan’s Principle – CHRT Rulings • A child resident on or off reserve who is registered or eligible to be registered under the Indian Act, as amended from time to time; • A child resident on or off reserve who has one parent/guardian who is registered or eligible to be registered under the Indian Act; • A child resident on or off reserve who is recognized by their Nation for the purposes of Jordan’s Principle; or • The child is ordinarily resident on reserve. • Apply Jordan’s Principle based on the needs of the child (not just limited to the normative standard of care); • Ensure that administrative procedures do not delay service provision; and • Respond to most cases within 48 hours.

Developments in ISC related to Jordan's Principle Support in navigating and accessing services Internal option to review decisions

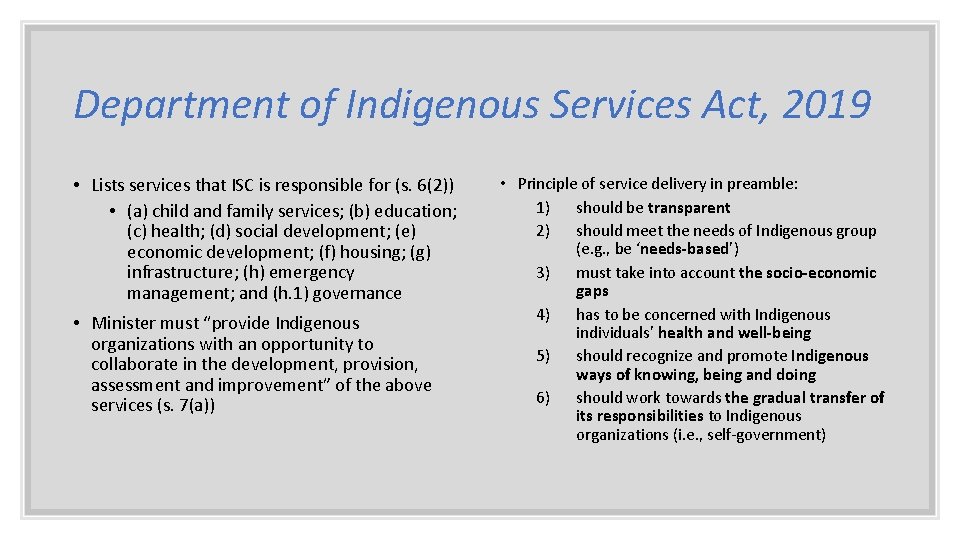

Department of Indigenous Services Act, 2019 • Lists services that ISC is responsible for (s. 6(2)) • (a) child and family services; (b) education; (c) health; (d) social development; (e) economic development; (f) housing; (g) infrastructure; (h) emergency management; and (h. 1) governance • Minister must “provide Indigenous organizations with an opportunity to collaborate in the development, provision, assessment and improvement” of the above services (s. 7(a)) • Principle of service delivery in preamble: 1) should be transparent 2) should meet the needs of Indigenous group (e. g. , be ‘needs-based’) 3) must take into account the socio-economic gaps 4) has to be concerned with Indigenous individuals’ health and well-being 5) should recognize and promote Indigenous ways of knowing, being and doing 6) should work towards the gradual transfer of its responsibilities to Indigenous organizations (i. e. , self-government)

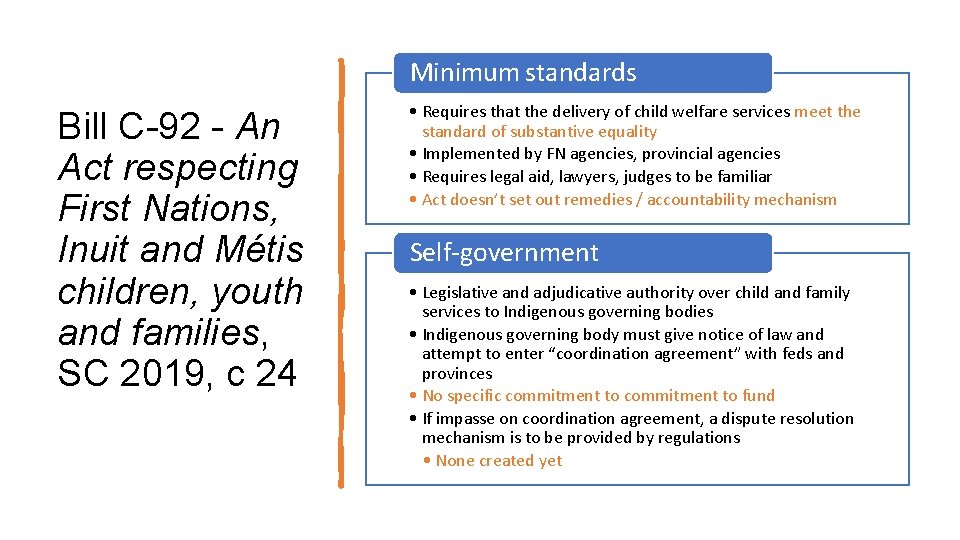

Minimum standards Bill C-92 - An Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families, SC 2019, c 24 • Requires that the delivery of child welfare services meet the standard of substantive equality • Implemented by FN agencies, provincial agencies • Requires legal aid, lawyers, judges to be familiar • Act doesn’t set out remedies / accountability mechanism Self-government • Legislative and adjudicative authority over child and family services to Indigenous governing bodies • Indigenous governing body must give notice of law and attempt to enter “coordination agreement” with feds and provinces • No specific commitment to fund • If impasse on coordination agreement, a dispute resolution mechanism is to be provided by regulations • None created yet

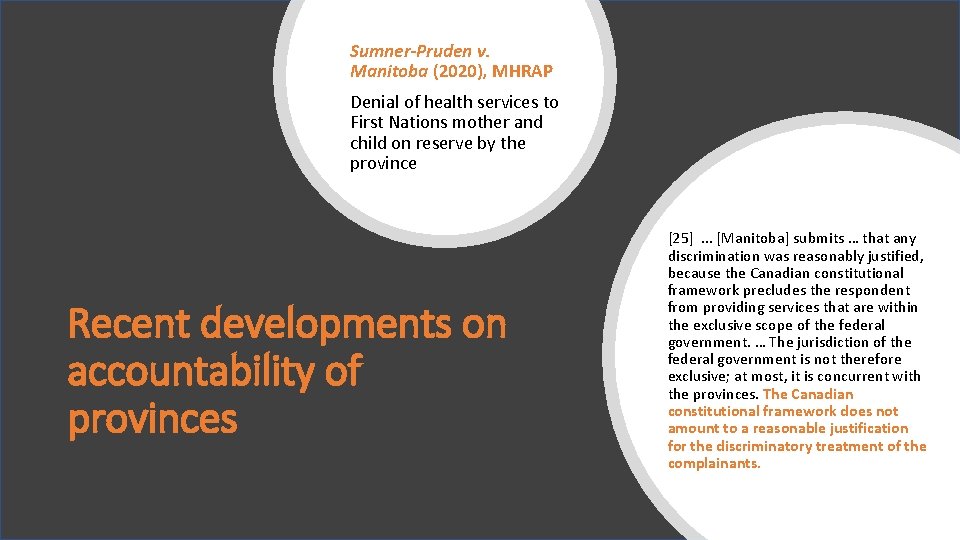

Sumner-Pruden v. Manitoba (2020), MHRAP Denial of health services to First Nations mother and child on reserve by the province Recent developments on accountability of provinces [25]. . . [Manitoba] submits … that any discrimination was reasonably justified, because the Canadian constitutional framework precludes the respondent from providing services that are within the exclusive scope of the federal government. … The jurisdiction of the federal government is not therefore exclusive; at most, it is concurrent with the provinces. The Canadian constitutional framework does not amount to a reasonable justification for the discriminatory treatment of the complainants.

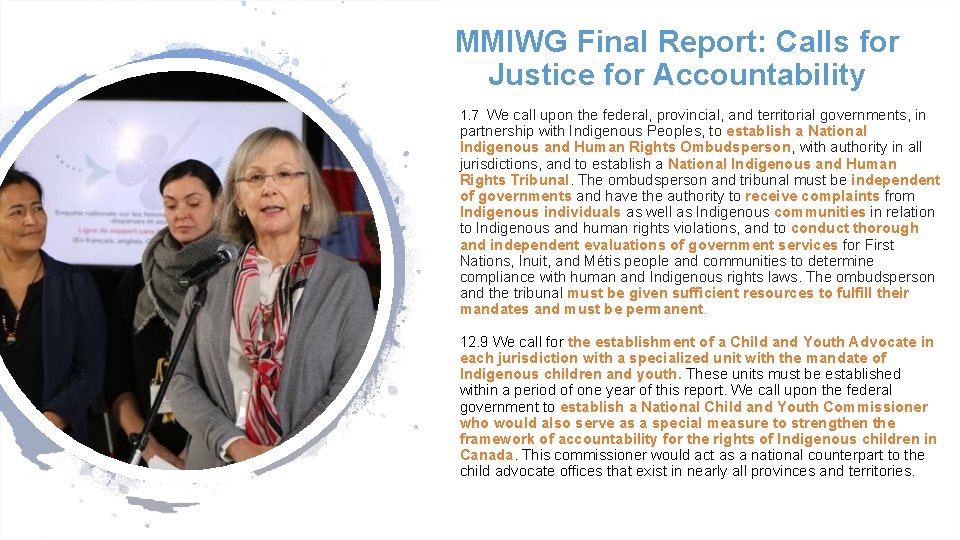

MMIWG Final Report: Calls for Justice for Accountability 1. 7 We call upon the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, in partnership with Indigenous Peoples, to establish a National Indigenous and Human Rights Ombudsperson, with authority in all jurisdictions, and to establish a National Indigenous and Human Rights Tribunal. The ombudsperson and tribunal must be independent of governments and have the authority to receive complaints from Indigenous individuals as well as Indigenous communities in relation to Indigenous and human rights violations, and to conduct thorough and independent evaluations of government services for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people and communities to determine compliance with human and Indigenous rights laws. The ombudsperson and the tribunal must be given sufficient resources to fulfill their mandates and must be permanent. 12. 9 We call for the establishment of a Child and Youth Advocate in each jurisdiction with a specialized unit with the mandate of Indigenous children and youth. These units must be established within a period of one year of this report. We call upon the federal government to establish a National Child and Youth Commissioner who would also serve as a special measure to strengthen the framework of accountability for the rights of Indigenous children in Canada. This commissioner would act as a national counterpart to the child advocate offices that exist in nearly all provinces and territories.

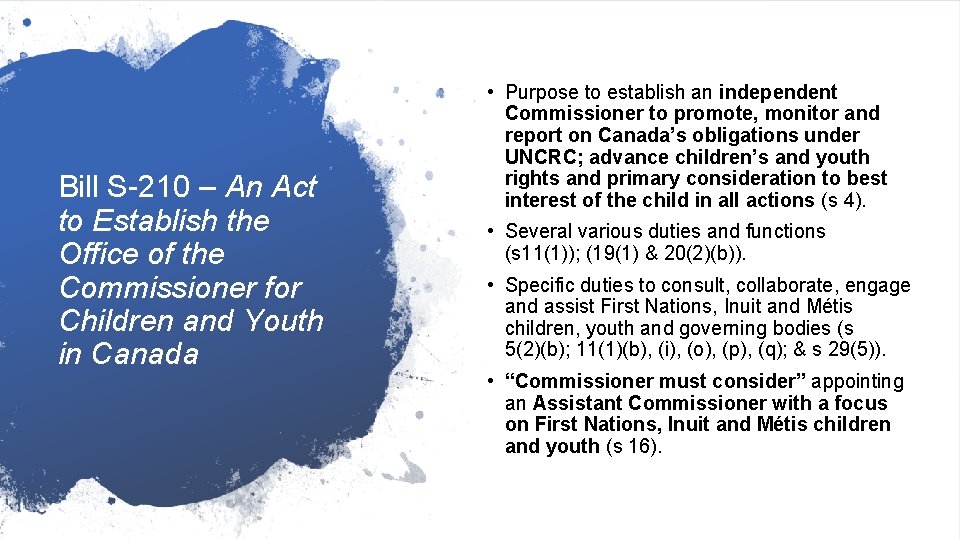

Bill S-210 – An Act to Establish the Office of the Commissioner for Children and Youth in Canada • Purpose to establish an independent Commissioner to promote, monitor and report on Canada’s obligations under UNCRC; advance children’s and youth rights and primary consideration to best interest of the child in all actions (s 4). • Several various duties and functions (s 11(1)); (19(1) & 20(2)(b)). • Specific duties to consult, collaborate, engage and assist First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and governing bodies (s 5(2)(b); 11(1)(b), (i), (o), (p), (q); & s 29(5)). • “Commissioner must consider” appointing an Assistant Commissioner with a focus on First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and youth (s 16).

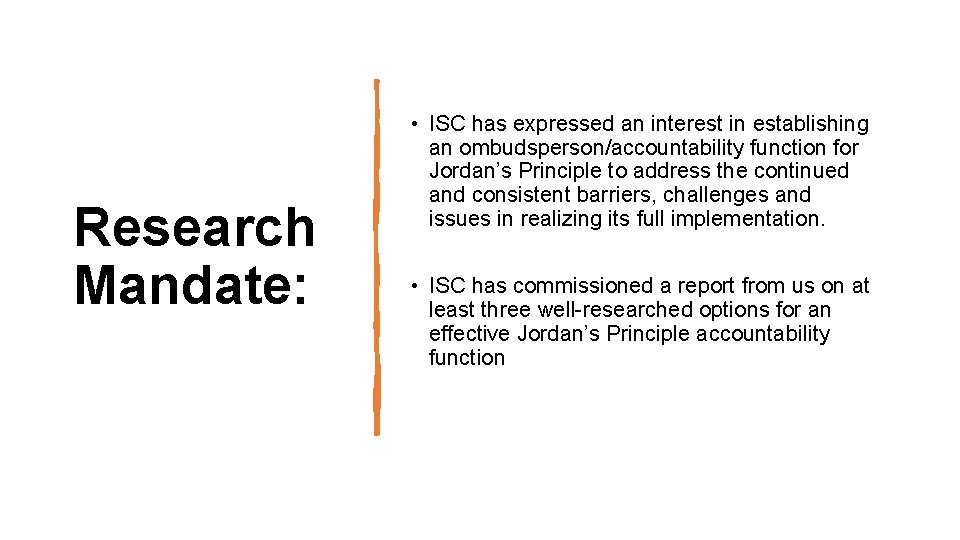

Research Mandate: • ISC has expressed an interest in establishing an ombudsperson/accountability function for Jordan’s Principle to address the continued and consistent barriers, challenges and issues in realizing its full implementation. • ISC has commissioned a report from us on at least three well-researched options for an effective Jordan’s Principle accountability function

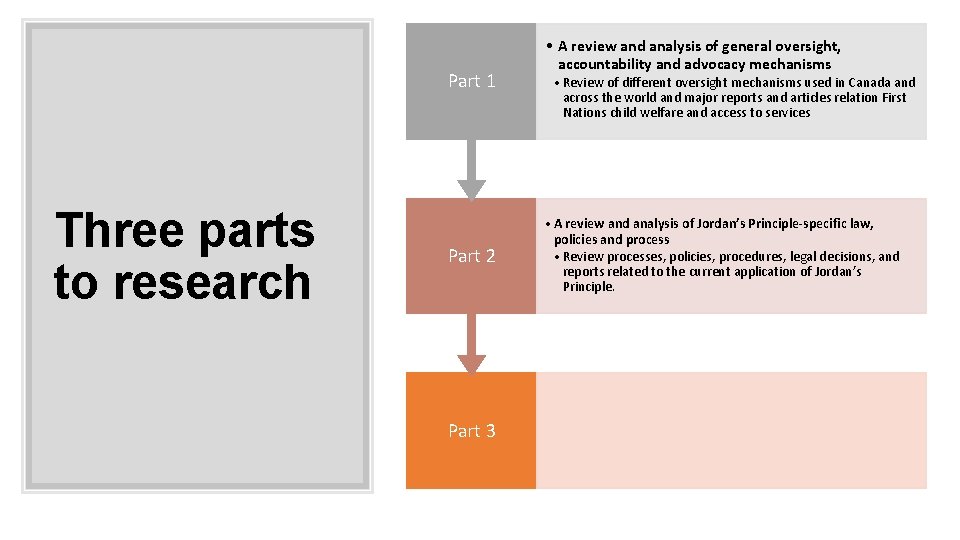

Part 1 Three parts to research Part 2 Part 3 • A review and analysis of general oversight, accountability and advocacy mechanisms • Review of different oversight mechanisms used in Canada and across the world and major reports and articles relation First Nations child welfare and access to services • A review and analysis of Jordan’s Principle-specific law, policies and process • Review processes, policies, procedures, legal decisions, and reports related to the current application of Jordan’s Principle.

It is all about accountability… • Accountability of who? • ISC • Provincial governments? • More? • Accountability by who? • Child Advocate? • Ombuds? • Tribunal? • How best to hold accountability? • • • Mediation, advice Quiet advocacy Oversight, access, reporting Liaising / connecting Ordering

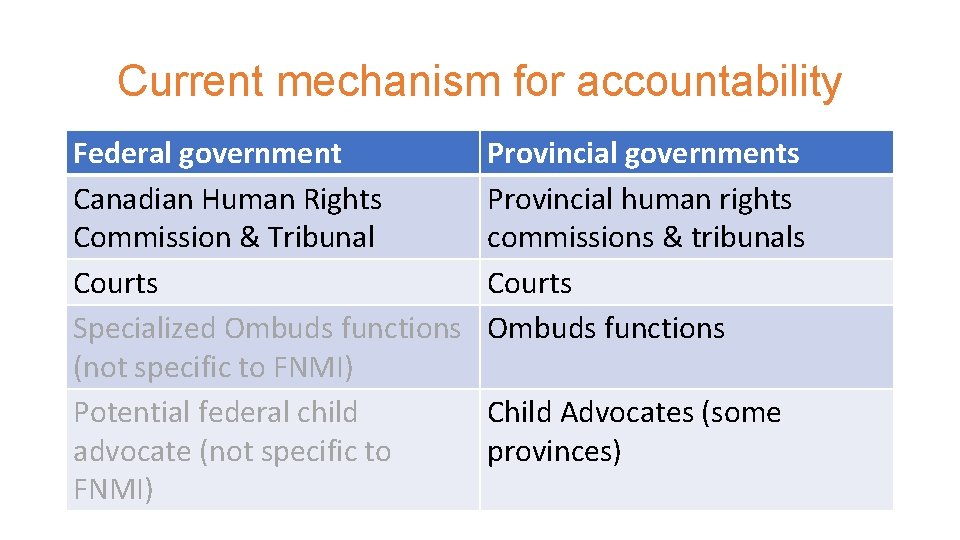

Current mechanism for accountability Federal government Canadian Human Rights Commission & Tribunal Courts Specialized Ombuds functions (not specific to FNMI) Potential federal child advocate (not specific to FNMI) Provincial governments Provincial human rights commissions & tribunals Courts Ombuds functions Child Advocates (some provinces)

KEY HIGHLIGHTS OF ACCOUNTABILILTL Y MECHANISMS • Play a key role in addressing problems • Over time, the role, structures and approaches to accountability have evolved. • Elements and considerations for accountability mechanisms • Advantages over court process • Concerns over lack of enforcement abilities

Next Step - Key Stakeholder Discussions We are kindly reaching out to see who may be interested in providing helpful feedback and/or in participating in key stakeholder discussions. If anyone is interested, please contact Shelby Thomas via email at Shelby. rae. tyler. thomas@gmail. com When contacting we would kindly ask that you let us know if there any specific discussion you would particularly be interested any background information with respect to your relationship with Jordan’s Principle.

- Slides: 17