Joint Hospital Surgical Grand Round Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Joint Hospital Surgical Grand Round Abdominal Compartment Syndrome --- surgical management Bear Cho Kam Wah North District Hospital 2013/07/27

Outline Background of abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) Surgical management Decompressive laparotomy Temporary abdominal closure Definitive abdominal closure

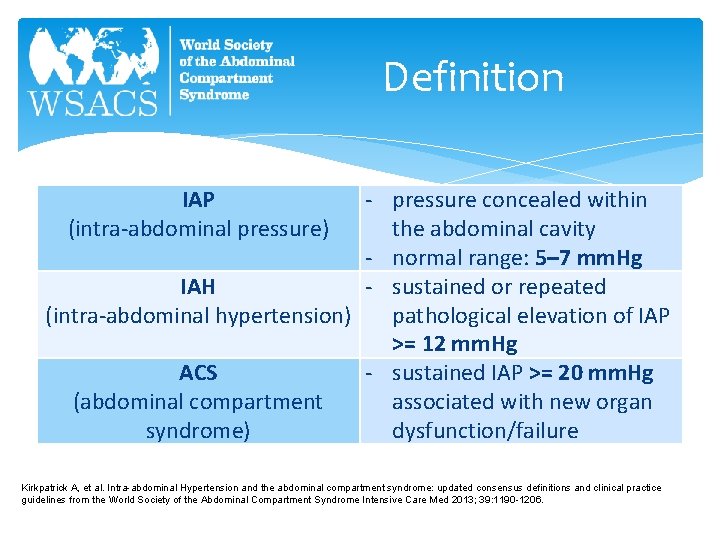

Definition - pressure concealed within the abdominal cavity - normal range: 5– 7 mm. Hg IAH - sustained or repeated (intra-abdominal hypertension) pathological elevation of IAP >= 12 mm. Hg ACS - sustained IAP >= 20 mm. Hg (abdominal compartment associated with new organ syndrome) dysfunction/failure IAP (intra-abdominal pressure) Kirkpatrick A, et al. Intra-abdominal Hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1190 -1206.

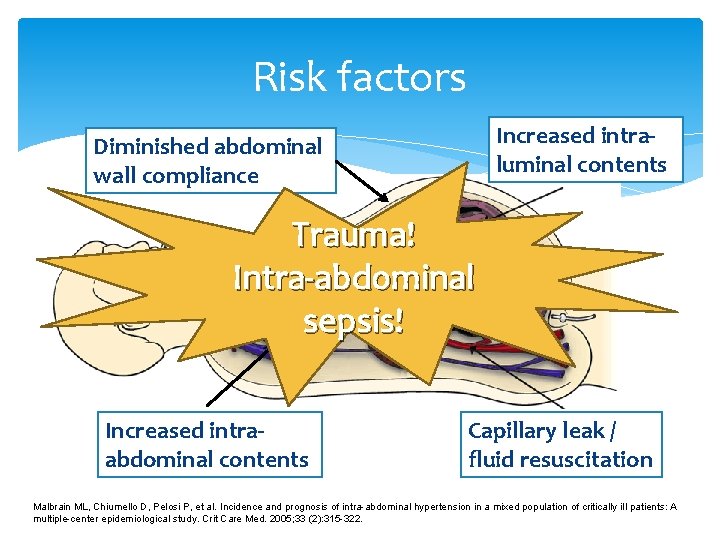

Risk factors Increased intraluminal contents Diminished abdominal wall compliance Trauma! Intra-abdominal sepsis! Increased intraabdominal contents Capillary leak / fluid resuscitation Malbrain ML, Chiumello D, Pelosi P, et al. Incidence and prognosis of intra-abdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients: A multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33 (2): 315 -322.

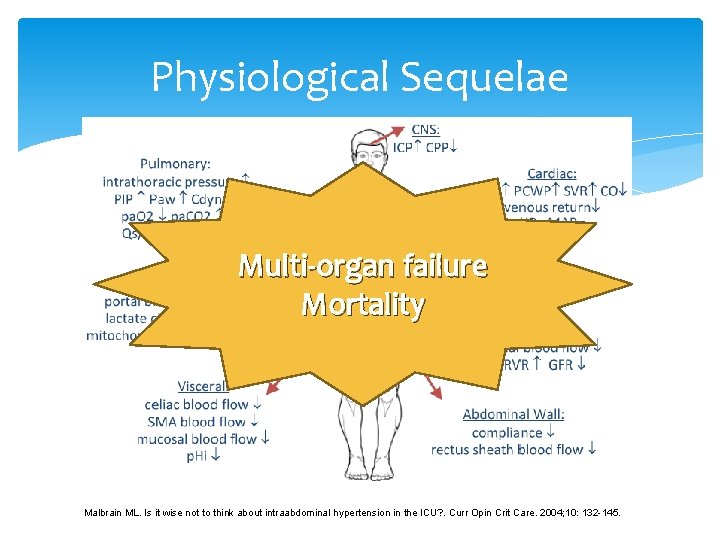

Physiological Sequelae Multi-organ failure Mortality Malbrain ML. Is it wise not to think about intraabdominal hypertension in the ICU? . Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004; 10: 132 -145.

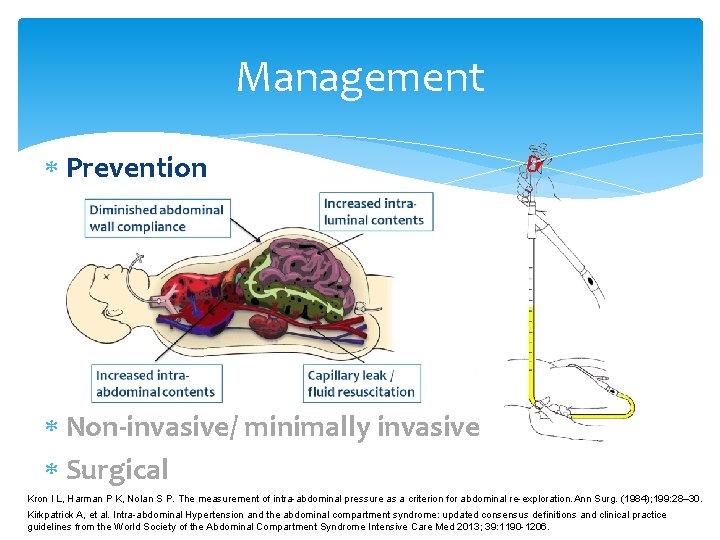

Management Prevention Non-invasive/ minimally invasive Surgical Kron I L, Harman P K, Nolan S P. The measurement of intra-abdominal pressure as a criterion for abdominal re-exploration. Ann Surg. (1984); 199: 28– 30. Kirkpatrick A, et al. Intra-abdominal Hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1190 -1206.

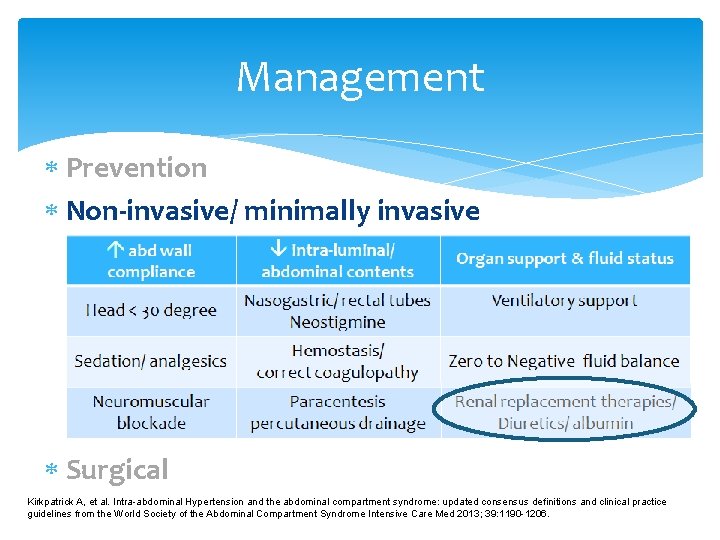

Management Prevention Non-invasive/ minimally invasive Surgical Kirkpatrick A, et al. Intra-abdominal Hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1190 -1206.

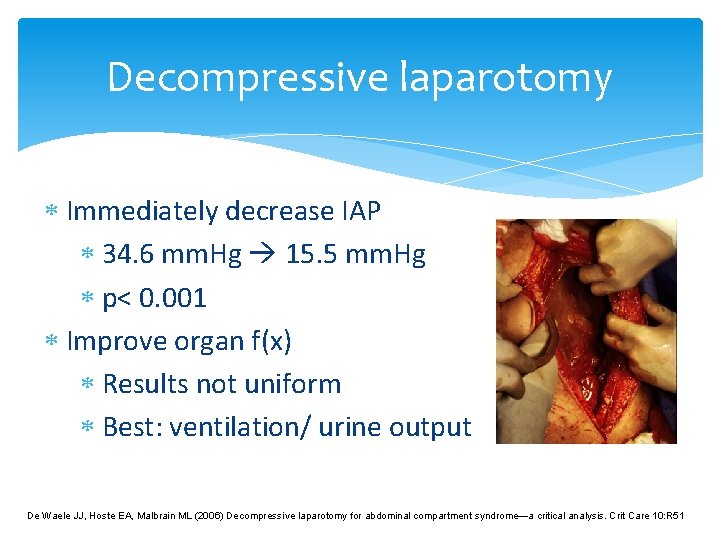

Decompressive laparotomy Immediately decrease IAP 34. 6 mm. Hg 15. 5 mm. Hg p< 0. 001 Improve organ f(x) Results not uniform Best: ventilation/ urine output De Waele JJ, Hoste EA, Malbrain ML (2006) Decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome—a critical analysis. Crit Care 10: R 51

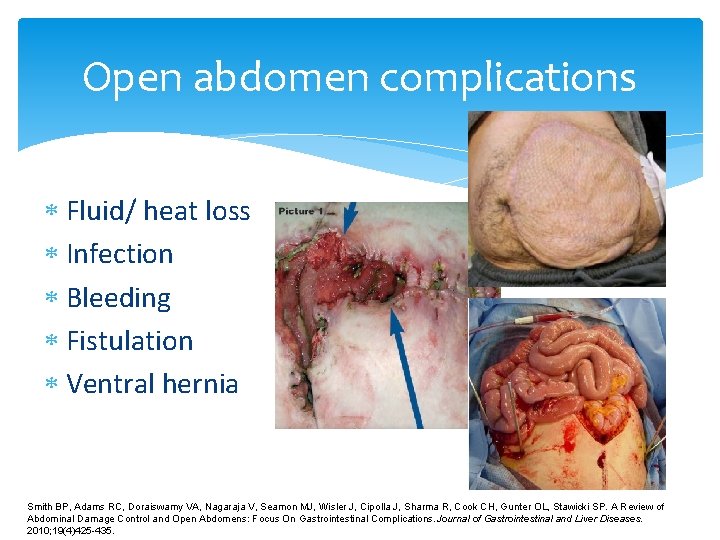

Open abdomen complications Fluid/ heat loss Infection Bleeding Fistulation Ventral hernia Smith BP, Adams RC, Doraiswamy VA, Nagaraja V, Seamon MJ, Wisler J, Cipolla J, Sharma R, Cook CH, Gunter OL, Stawicki SP. A Review of Abdominal Damage Control and Open Abdomens: Focus On Gastrointestinal Complications. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 2010; 19(4)425 -435.

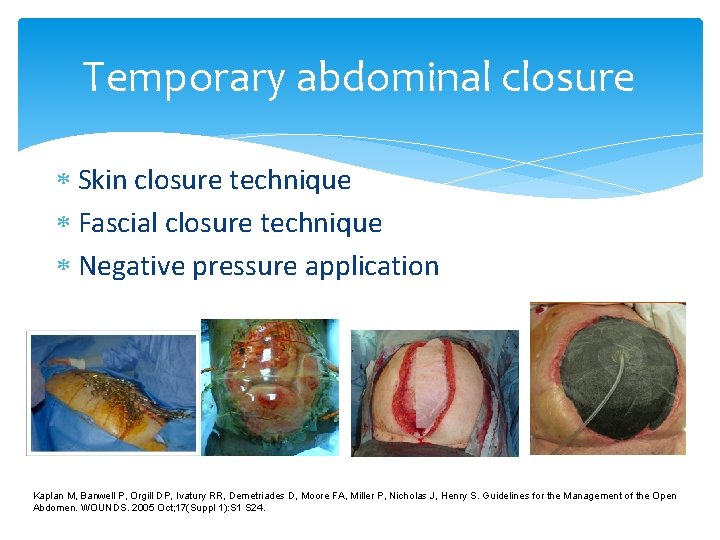

Temporary abdominal closure Skin closure technique Fascial closure technique Negative pressure application Kaplan M, Banwell P, Orgill DP, Ivatury RR, Demetriades D, Moore FA, Miller P, Nicholas J, Henry S. Guidelines for the Management of the Open Abdomen. WOUNDS. 2005 Oct; 17(Suppl 1): S 1 S 24.

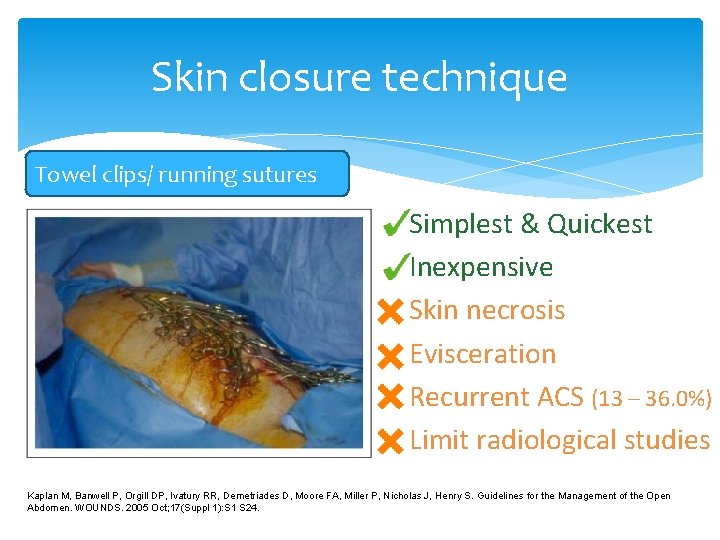

Skin closure technique Towel clips/ running sutures Simplest & Quickest Inexpensive Skin necrosis Evisceration Recurrent ACS (13 – 36. 0%) Limit radiological studies Kaplan M, Banwell P, Orgill DP, Ivatury RR, Demetriades D, Moore FA, Miller P, Nicholas J, Henry S. Guidelines for the Management of the Open Abdomen. WOUNDS. 2005 Oct; 17(Suppl 1): S 1 S 24.

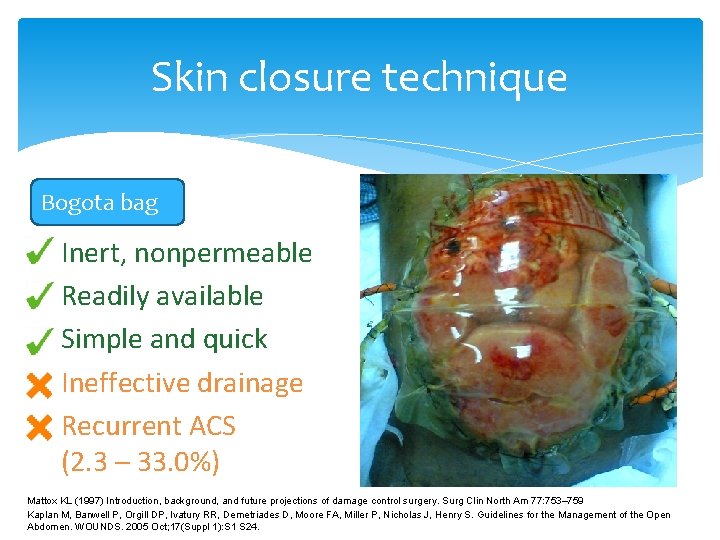

Skin closure technique Bogota bag Inert, nonpermeable Readily available Simple and quick Ineffective drainage Recurrent ACS (2. 3 – 33. 0%) Mattox KL (1997) Introduction, background, and future projections of damage control surgery. Surg Clin North Am 77: 753– 759 Kaplan M, Banwell P, Orgill DP, Ivatury RR, Demetriades D, Moore FA, Miller P, Nicholas J, Henry S. Guidelines for the Management of the Open Abdomen. WOUNDS. 2005 Oct; 17(Suppl 1): S 1 S 24.

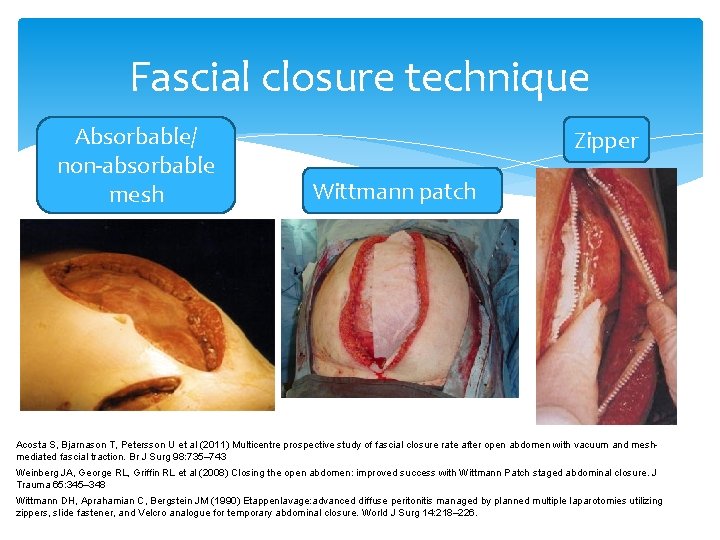

Fascial closure technique Absorbable/ non-absorbable mesh Zipper Wittmann patch Acosta S, Bjarnason T, Petersson U et al (2011) Multicentre prospective study of fascial closure rate after open abdomen with vacuum and meshmediated fascial traction. Br J Surg 98: 735– 743 Weinberg JA, George RL, Griffin RL et al (2008) Closing the open abdomen: improved success with Wittmann Patch staged abdominal closure. J Trauma 65: 345– 348 Wittmann DH, Aprahamian C, Bergstein JM (1990) Etappenlavage: advanced diffuse peritonitis managed by planned multiple laparotomies utilizing zippers, slide fastener, and Velcro analogue for temporary abdominal closure. World J Surg 14: 218– 226.

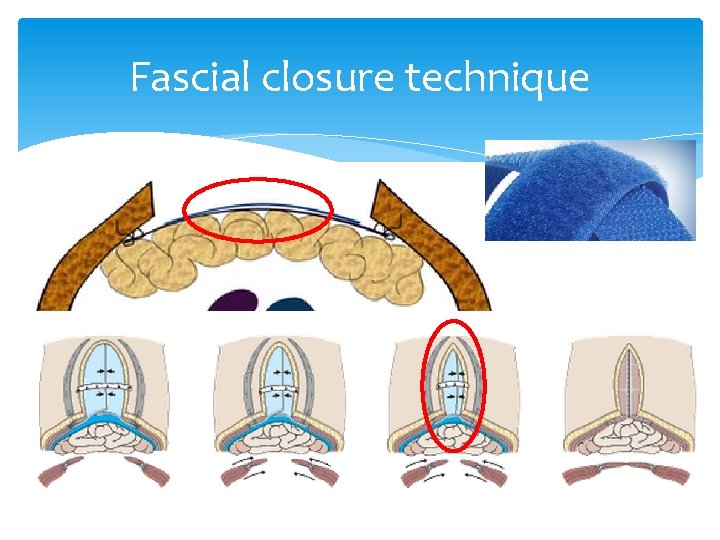

Fascial closure technique

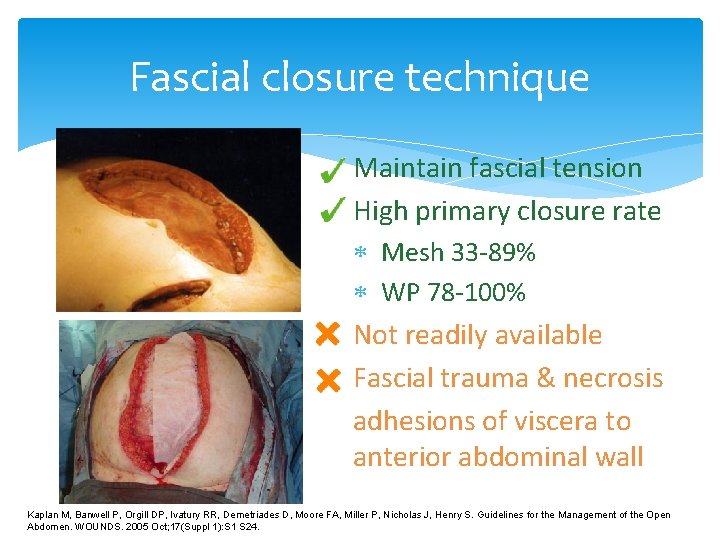

Fascial closure technique Maintain fascial tension High primary closure rate Mesh 33 -89% WP 78 -100% Not readily available Fascial trauma & necrosis adhesions of viscera to anterior abdominal wall Kaplan M, Banwell P, Orgill DP, Ivatury RR, Demetriades D, Moore FA, Miller P, Nicholas J, Henry S. Guidelines for the Management of the Open Abdomen. WOUNDS. 2005 Oct; 17(Suppl 1): S 1 S 24.

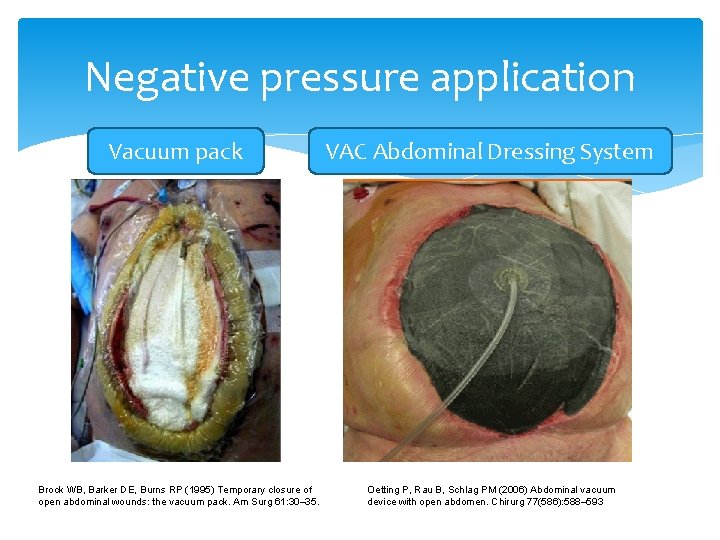

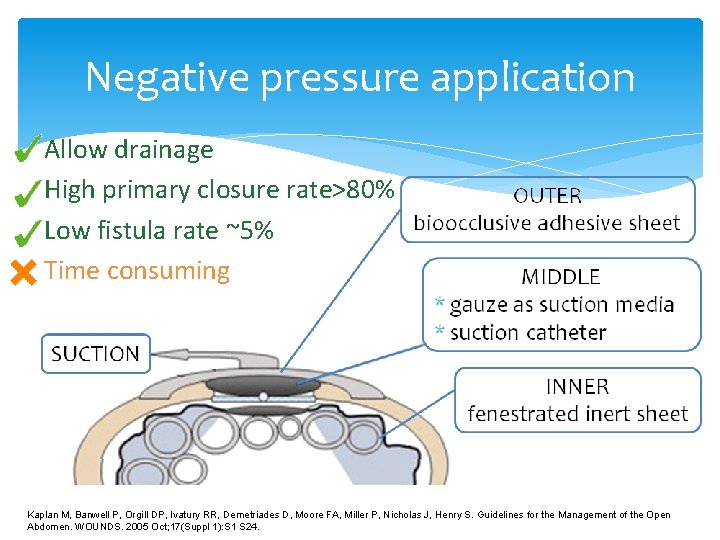

Negative pressure application Vacuum pack Brock WB, Barker DE, Burns RP (1995) Temporary closure of open abdominal wounds: the vacuum pack. Am Surg 61: 30– 35. VAC Abdominal Dressing System Oetting P, Rau B, Schlag PM (2006) Abdominal vacuum device with open abdomen. Chirurg 77(586): 588– 593

Negative pressure application Allow drainage High primary closure rate>80% Low fistula rate ~5% Time consuming Kaplan M, Banwell P, Orgill DP, Ivatury RR, Demetriades D, Moore FA, Miller P, Nicholas J, Henry S. Guidelines for the Management of the Open Abdomen. WOUNDS. 2005 Oct; 17(Suppl 1): S 1 S 24.

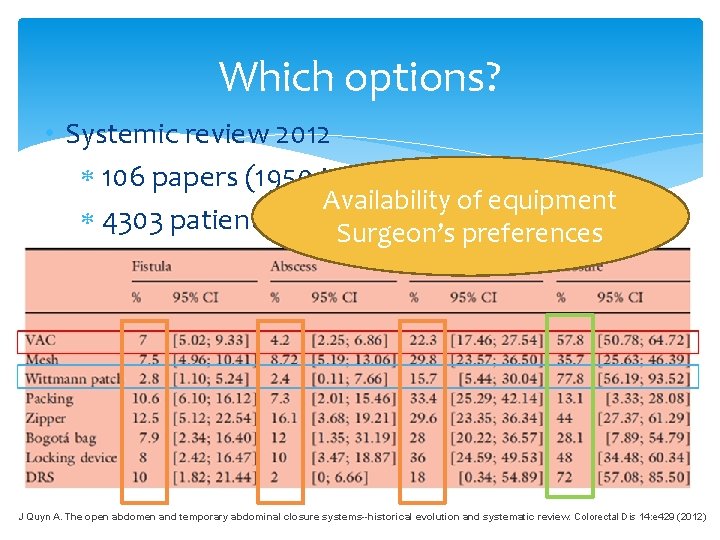

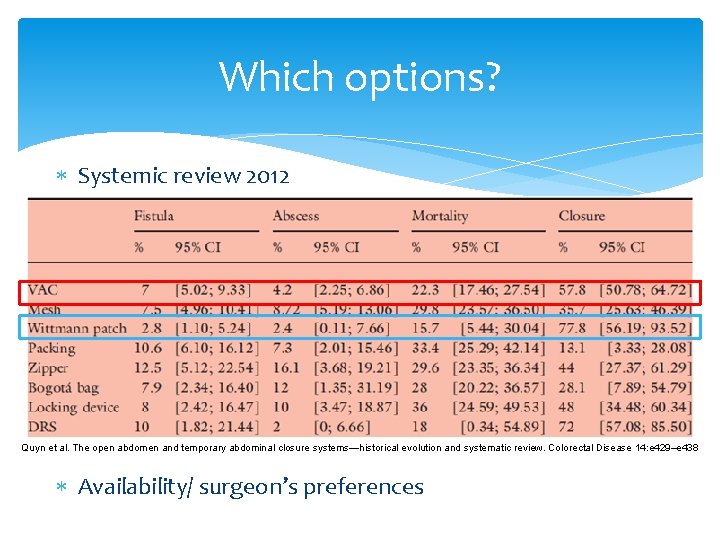

Which options? • Systemic review 2012 106 papers (1950 to 2009) Availability of equipment 4303 patients Surgeon’s preferences J Quyn A. The open abdomen and temporary abdominal closure systems--historical evolution and systematic review. Colorectal Dis 14: e 429 (2012)

Aftercare Review frequently Recurrent ACS Organ support/ fluid status Treat primary pathology Early definitive closure

Definitive closure Primary Closure Prosthesis Nonabsorbable mesh Biologic materials Plastic surgery technique Tissue expander Rotational / free flap Component separation

Primary closure Most preferable Without tension

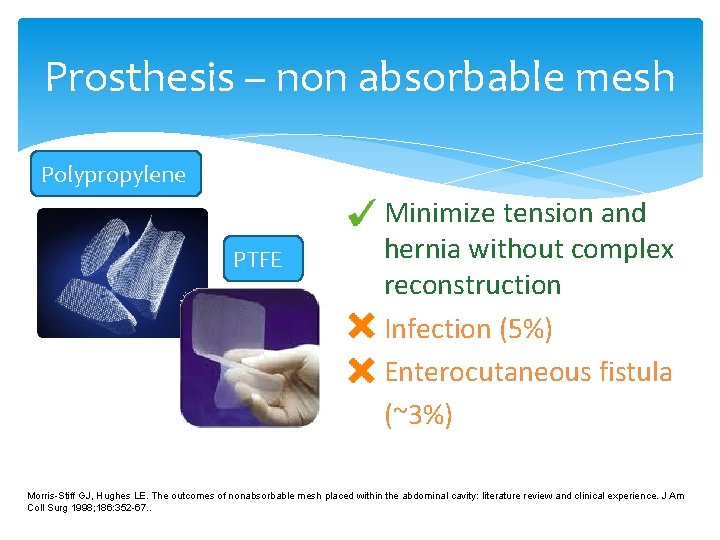

Prosthesis – non absorbable mesh Polypropylene PTFE Minimize tension and hernia without complex reconstruction Infection (5%) Enterocutaneous fistula (~3%) Morris-Stiff GJ, Hughes LE. The outcomes of nonabsorbable mesh placed within the abdominal cavity: literature review and clinical experience. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 186: 352 -67. .

Prosthesis – biologic materials Porcine small intestinal submucosa Human acellular dermis • Acellular extracellular matrix • Type I collagen • Vascular endothelial growth factors & fibroblast growth factors Resist infection Long term outcome expensive Franklin Jr, JJ Gonzalez Jr, ME Michaelson RP, Glass JL, Chock DA. Preliminary experience with new bioactive prosthetic material for repair of hernias in infected fields. Hernia 2002; 6: 171 -4. Menon NG, Rodriguez ED, Byrnes CK, Girotto JA, Goldberg NH, Silverman RP. Rvascularization of human acellular dermis in full-thickness abdominal wall reconstruction in the rabbit model. Ann Plast Surg 2003; 50: 523 -7.

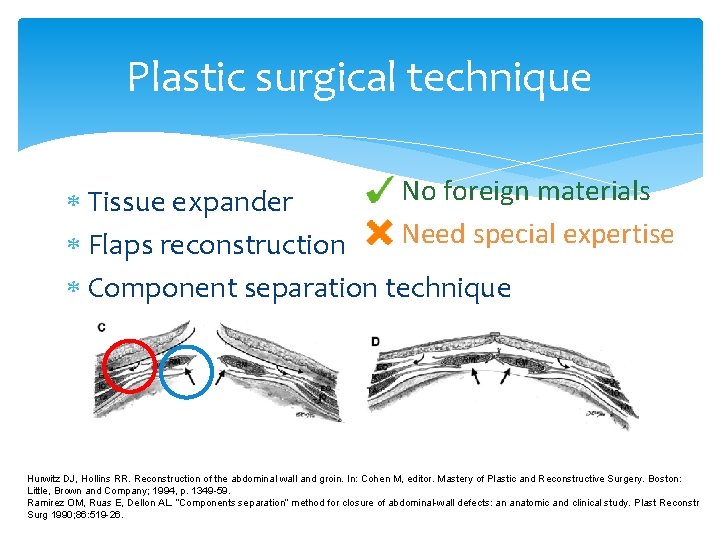

Plastic surgical technique No foreign materials Tissue expander Need special expertise Flaps reconstruction Component separation technique Hurwitz DJ, Hollins RR. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall and groin. In: Cohen M, editor. Mastery of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1994, p. 1349 -59. Ramirez OM, Ruas E, Dellon AL. “Components separation” method for closure of abdominal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr Surg 1990; 86: 519 -26.

Summary Trauma/ intra-abdominal sepsis Multi-organ failure and mortality Decompressive laparotomy Temporary abdominal closure Early definitive abdominal closure

Thank you!

Background 1890 s: elevated intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) death 1910 s: association of elevated IAP to respiratory, cardiovascular, renal and various other organ systems 1980: Kron 1 first used the term abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) to describe the pathophysiology resulting from elevated IAP secondary to aortic aneurysm surgery now: ACS the cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal, splanchnic, abdominal wall/wound and intracranial disturbances resulting from elevated IAP regardless of etiology 1 Kron I L, Harman P K, Nolan S P. The measurement of intra-abdominal pressure as a criterion for abdominal re-exploration. Ann Surg. (1984); 199: 28– 30.

Epidemiology 5 -15% in ICU admissions/ 1% of general admissions no evidence on racial, sexual, and age-related differences

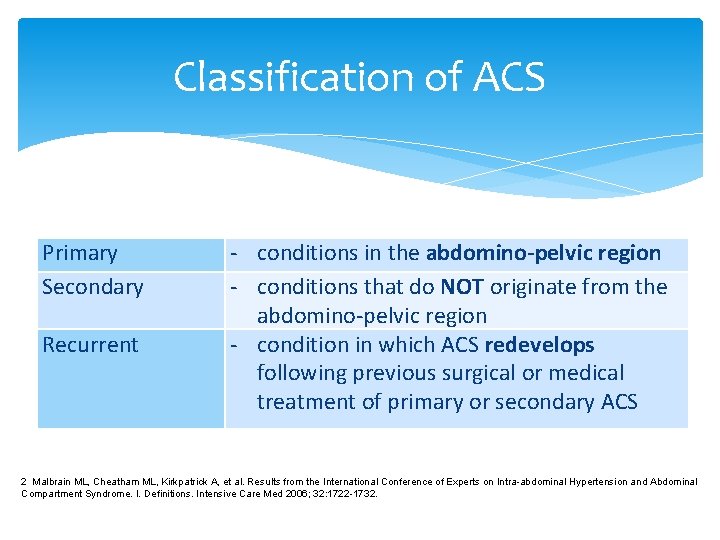

Classification of ACS Primary Secondary Recurrent - conditions in the abdomino-pelvic region - conditions that do NOT originate from the abdomino-pelvic region - condition in which ACS redevelops following previous surgical or medical treatment of primary or secondary ACS 2 Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML, Kirkpatrick A, et al. Results from the International Conference of Experts on Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. I. Definitions. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32: 1722 -1732.

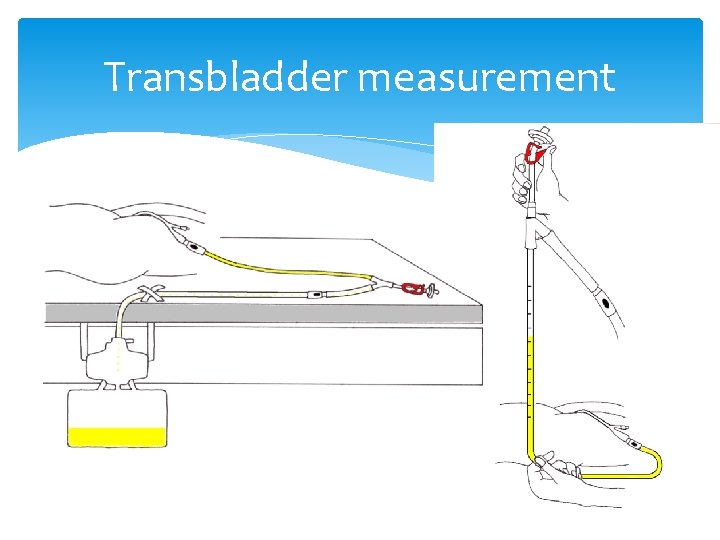

Transbladder measurement

Risk factors 1. Diminished abdominal wall compliance Acute respiratory failure, especially with elevated intrathoracic pressure Abdominal surgery with primary fascial or tight closure Major trauma / burns Prone positioning, head of bed > 30 degrees High body mass index (BMI), central obesity 2. Increased intra-abdominal contents 3. Capillary leak / fluid resuscitation

Risk factors 1. Diminished abdominal wall compliance 2. Increased intra-abdominal contents hemoperitoneum ascites pneumoperitoneum intraluminal: gastroparesis, ileus, pseudo-obstruction 3. Capillary leak / fluid resuscitation

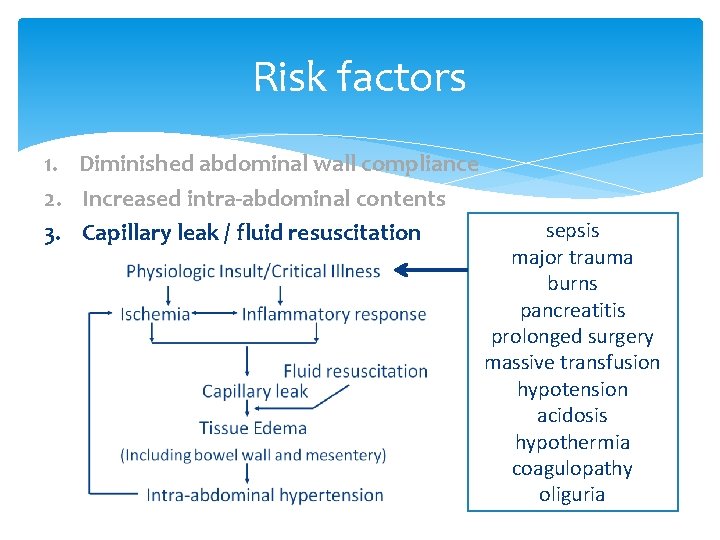

Risk factors 1. Diminished abdominal wall compliance 2. Increased intra-abdominal contents 3. Capillary leak / fluid resuscitation sepsis major trauma burns pancreatitis prolonged surgery massive transfusion hypotension acidosis hypothermia coagulopathy oliguria

Prognosis - ~100% fatal if left untreated mortality of 25 -75% despite treatment

CT Guide surgical treatment/ radiological intervention

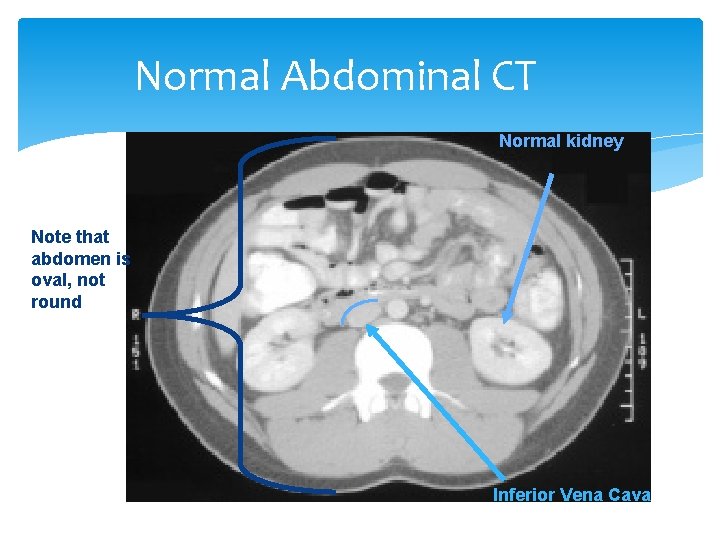

Normal Abdominal CT Normal kidney Note that abdomen is oval, not round Inferior Vena Cava

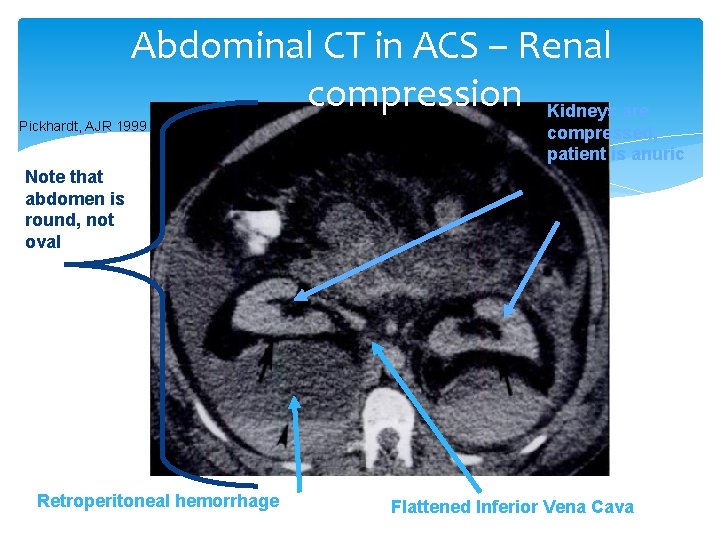

Abdominal CT in ACS – Renal compression Kidneys are Pickhardt, AJR 1999 compressed, patient is anuric Note that abdomen is round, not oval Retroperitoneal hemorrhage Flattened Inferior Vena Cava

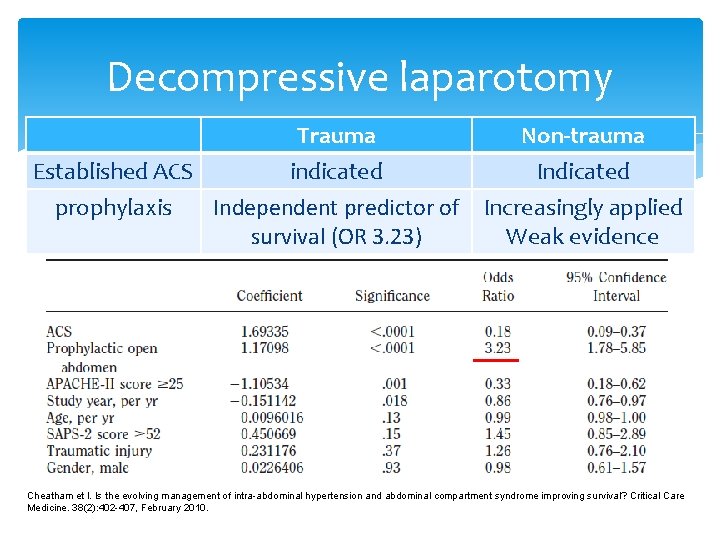

Decompressive laparotomy Trauma Non-trauma Established ACS indicated Indicated prophylaxis Independent predictor of Increasingly applied survival (OR 3. 23) Weak evidence Cheatham et l. Is the evolving management of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome improving survival? Critical Care Medicine. 38(2): 402 -407, February 2010.

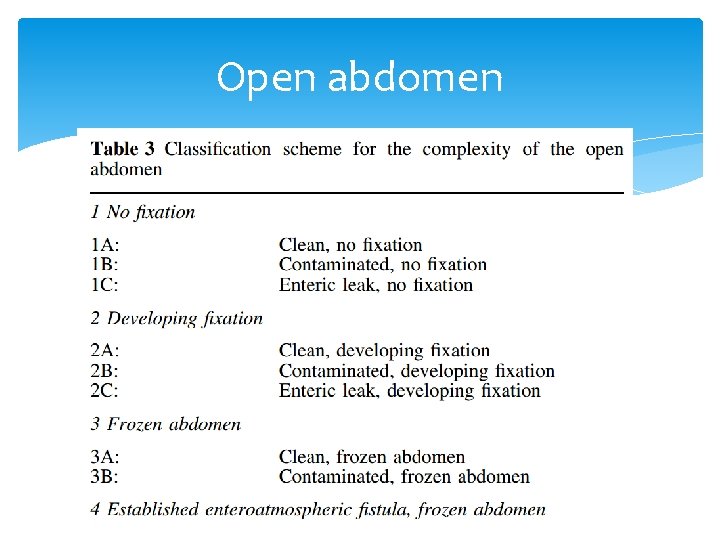

Open abdomen

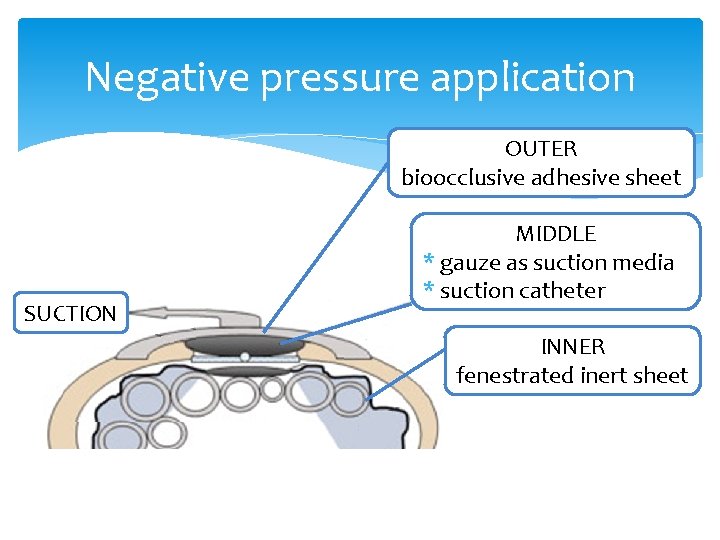

Negative pressure application OUTER bioocclusive adhesive sheet SUCTION MIDDLE * gauze as suction media * suction catheter INNER fenestrated inert sheet

Which options? Systemic review 2012 Quyn et al. The open abdomen and temporary abdominal closure systems—historical evolution and systematic review. Colorectal Disease 14: e 429–e 438 Availability/ surgeon’s preferences

- Slides: 42