John Donne 1572 1631 Context John Donne was

- Slides: 15

John Donne 1572 -1631: Context John Donne was born in London in 1572 to a prosperous Roman Catholic family - a dangerous thing at a time when anti. Catholic feeling was rife in England. Donne's first teachers were Jesuits and at the age of 11, Donne and his younger brother Henry were entered the University of Oxford, where Donne studied for three years. He spent the next three years at the University of Cambridge, but took no degree at either university because he would not take the Oath of Supremacy I(recognizing the King as the head of the Church) required at graduation. He was admitted to study law at Lincoln's Inn (1592), and it seemed that Donne should follow a legal or diplomatic career. In 1593, Donne's brother Henry died of a fever in prison after being arrested for giving sanctuary to a Catholic priest. This made Donne begin to question his faith. His first book of poems, Satires, written during this period is considered one of Donne's most important literary efforts. Having inherited a considerable fortune, young "Jack Donne" spent his money on womanizing, on books, at theatre, and on travels. In 1597, Donne joined an expedition to the Azores, where he wrote "The Calm". Upon his return to England in 1598, Donne was appointed private secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, afterward Lord Ellesmere. Donne was beginning a promising career. In 1601, Donne became MP for Brackley, and sat in Queen Elizabeth's last Parliament. But in the same year, he secretly married Lady Egerton's niece, seventeen-year-old Anne More, daughter of Sir George More, Lieutenant of the Tower, and effectively committed career suicide. Sir George had Donne thrown in Fleet Prison for some weeks, along with his cohorts Samuel and Christopher Brooke who had aided the couple's clandestine affair. Donne was dismissed from his post, and for the next decade had to struggle near poverty to support his growing family. It was not until 1609 that a reconciliation was effected between Donne and his father-in-law, and Sir George More was finally induced to pay his daughter's dowry.

As Donne approached forty, he published two anti-Catholic polemics Pseudo-Martyr (1610) and Ignatius his Conclave(1611). They were final public proof of Donne's renunciation of the Catholic faith. Pseudo-Martyr, which held that English Catholics could pledge an oath of allegiance to James I, King of England, without compromising their religious loyalty to the Pope, won Donne the favour of the King. Donne had refused to take Anglican orders in 1607, but King James persisted, finally announcing that Donne would receive no post or favour from the King, unless in the church. In 1615, Donne reluctantly entered the ministry and was appointed a Royal Chaplain later that year. In 1616, he was appointed Reader in Divinity at Lincoln's Inn (Cambridge had conferred the degree of Doctor of Divinity on him two years earlier). Donne's style, full of elaborate metaphors and religious symbolism, his flair for drama, his wide learning and his quick wit soon established him as one of the greatest preachers of the era. Just as Donne's fortunes seemed to be improving, Anne Donne died, on 15 August, 1617, aged thirty-three, after giving birth to their twelfth child, a stillborn. Struck by grief, Donne wrote the seventeenth Holy Sonnet, "Since she whom I lov'd hath paid her last debt. " According to Donne's friend and biographer, Izaak Walton, Donne was thereafter 'crucified to the world'. Donne continued to write poetry, notably his Holy Sonnets (1618), but the time for love songs was over. In 1618, Donne went as chaplain with Viscount Doncaster in his embassy to the German princes. Donne's private meditations, Devotions upon Emergent Occasions, written while he was recovering from a serious illness, were published in 1624. The most famous of these is undoubtedly Meditation 17, which includes the immortal lines "No man island" and "never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee. " In 1624, Donne was made vicar of St Dunstan's-in-the-West. On March 27, 1625, James I died, and Donne preached his first sermon for Charles I. But for his ailing health, (he had mouth sores and had experienced significant weight loss) Donne almost certainly would have become a bishop in 1630. Obsessed with the idea of death, Donne posed in a shroud - the painting was completed a few weeks before his death, and later used to create an effigy. He also preached what was called his own funeral sermon, Death's Duel, just a few weeks before he died in London on March 31, 1631. The last thing Donne wrote just before his death was Hymne to God, my God, In my Sicknesse. Donne's monument, in his shroud, survived the Great Fire of London and can still be seen today at St. Paul's.

John Donne: Context (Metaphysicals) • Metaphysical poetry is concerned with the whole experience of man, but the intelligence, learning and seriousness of the poets means that the poetry is about the profound areas of experience especially - about love, romantic and sensual; about man's relationship with God - the eternal perspective, and, to a less extent, about pleasure, learning and art. • Metaphysical poems are lyric poems. They are brief but intense meditations, characterized by striking use of wit, irony and wordplay. Beneath the formal structure (of rhyme, metre and stanza) is the underlying (and often hardly less formal) structure of the poem's argument. Note that there may be two (or more) kinds of argument in a poem.

Batter my heart, three-person'd God, for you (a) As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend; (b) That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend (b) Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new. (a) I, like an usurp'd town to'another due, Labor to'admit you, but oh, to no end; Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend, But is captiv'd, and proves weak or untrue. Yet dearly'I love you, and would be lov'd fain, But am betroth'd unto your enemy; Divorce me, 'untie or break that knot again, Take me to you, imprison me, for I, Except you'enthrall me, never shall be free, Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

The speaker asks the “three-personed God” to “batter” his heart, for as yet God only knocks politely, breathes, shines, and seeks to mend. The speaker says that to rise and stand, he needs God to overthrow him and bend his force to break, blow, and burn him, and to make him new. Like a town that has been captured by the enemy, which seeks unsuccessfully to admit the army of its allies and friends, the speaker works to admit God into his heart, but his Reason, like God’s deputy, has been captured by the enemy and proves “weak or untrue. ” Yet the speaker says that he loves God dearly and wants to be loved in return, but he is like a maiden who is betrothed (engaged) to God’s enemy. The speaker asks God to “divorce, untie, or break that knot again, ” to take him prisoner; for until he is God’s prisoner, he says, he will never be free, and he will never be chaste until God ravishes him.

This poem is an appeal to God, pleading with Him not for mercy or comfort or help but for a violent, almost brutal overmastering; thus, it implores God to perform actions that would usually be considered extremely sinful—from battering the speaker to actually raping him, which, he says in the final line, is the only way he will ever be chaste. The poem’s extended metaphors (the speaker’s heart as a captured town, the speaker as a maiden betrothed to God’s enemy) work with its extraordinary series of violent and powerful verbs (batter, o’erthrow, bend, break, blow, burn, divorce, untie, break, take, imprison, enthrall, ravish) to create the image of God as an overwhelming, violent conqueror. The bizarre nature of the speaker’s plea comes to a climax in the paradoxical final couplet, in which the speaker claims that only if God takes him prisoner can he be free, and only if God ravishes him can he be chaste (pure). As is amply illustrated by the contrast between Donne’s religious lyrics and his metaphysical love poems, Donne is a poet deeply divided between religious spirituality and a kind of carnal lust for life. Many of his best poems, including “Batter my heart, three-personed God, ” mix the discourse of the spiritual and the physical or of the holy and the secular. In this case, the speaker achieves that mix by claiming that he can only overcome sin and achieve spiritual purity if he is forced by God in the most physical, violent, and carnal terms imaginable.

Batter my Heart is number 14 of Donne’s collection The Holy Sonnets. The sonnet form used by Donne in Batter my Heart is complex. The octave form of the first part, with the rhyming scheme of abba definitely suggests the Petrarchan form. But as with other Donne sonnets, the sestet is somewhat of a mixed form, as Donne likes to get the clinching effect of the final couplet of the Shakespearean sonnet form. So, as with other sonnets, he rhymes cdcd ee. The iambic pentameter form of the sonnet is kept fairly rigidly. There are significant first foot inversions (ie. the first, not second syllable is stressed) in ‘Batter’, ‘Labour’ and ‘Reason’. The urgency of Donne’s plea is maintained through enjambment lines 1, 3 and significantly, 12. The many lists of words make extra stresses (as lines 2 and 4) and also for an interrupted and jerky reading, which mirrors Donne’s state of mind. Even a line like ‘Reason your viceroy in mee, mee should defend’ which seems to run smoothly enough to start with, has the deliberately awkward ‘mee, mee’ in the middle to force a caesura. Lines 9, 10 are the only ones to give a smooth reading, perhaps suggesting how tempting his present captivity still is to him.

The sentences are on the whole complex with many clauses suggesting the complexity of Donne relationship with God. This can be contrasted with the attitude of Southwell in ‘New Prince, New Pomp. ’ The opening sentence is imperative, with Donne almost pleading with God to ‘batter’ or overcome his heart. The overriding mood of the whole poem is imperative: ‘o’erthrow me’, ‘bend your force’, ‘make me new’, ‘divorce mee’ ‘imprison mee’ – a continuing and growing desire for God to become an active and forceful presence. The declarative mood is used to tell of Donne’s current state of ‘unfaithfulness’: ‘Yet dearly I love you, and would be loved faine, /But am betrothed unto your enemie. There is asyndetic listing ‘knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend’ to emphasise the functions that God already fulfils for Donne ’

Excessive use of personal pronouns, ‘I’ ‘mee’ (the speaker)combined with second person ‘you’ (God) emphasise that this is a private, intimate relationship. This is reiterated in the lexical field of the sestet. The many active verbs in the first quatrain suggest a variety of activities: from the domestic picture of a housewife cleaning and polishing to a blacksmith or metalworker bending into shape some obstinate object. The biblical image of a furnace used to shape us, as seen in Isaiah and Ezekiel, is echoed here. In the first quatrain, then, God has to be very active. These verbs continue to become the overriding word class of the poem, becoming increasingly violent. In the second quatrain Donne explains why. Try (‘Labour’) as he might, he just cannot seem to allow God to have control of his life. He knows God should govern his life, but it is as if he's been taken over by other forces, though he does not say what these forces might be. They might be apathy, or they may be more obviously evil. The lexical field of warfare and battle is used here in the second quatrain ‘ usurpt; defend; captiv’d’ to convey Donn’e metaphor of being a town that has been taken over by these forces. The modal auxilliary ‘Yet dearly I love you, and would be loved faine, ’ creates a sense of hope and potential. IF God is willing to batter and ravish him, he will gladly love in return. In the sestet, the speaker declares his continuing love for God, and his desire to receive God's love. Here the lexical field becomes very sexual (love; betroth’d; divorce; take mee; imprison; enthrall; chaste; ravish’. and the sense of a personal relationship that has been created by the personal pronouns is exploited. Unless God really acts and takes the speaker by force, he is never going to get out of his present spiritual state of sinfulness and indifference.

Under Siege In the second quatrain, the central image is of a besieged town, perhaps picking up on the opening word ‘Batter’, as in a battering ram to break down a city's gates. The simile is an extended one, as the poet works out its details. Reason is ‘your viceroy’, or governor, but is powerless to act. Donne is unable to reason himself into a better spiritual state. It is as though God's forces are outside, but Donne cannot get to the gates to let them in – hence the need for the battering ram. Cheating The imagery of the sestet is quite obviously a metaphor of marital unfaithfulness: ‘am betrothed unto our enemie’; ‘Divorce me’; ‘ravish mee’. It might seem shocking to use such completely human terminology for spiritual unfaithfulness, but, then, the Metaphysical poets do set out to shock In the sestet the imagery becomes markedly sexual – and paradoxical. Donne is portrayed as in love with God but betrothed to his enemy. In his time, when arranged marriages were not uncommon, this could happen. So the ‘Divorce mee’ means God is to dissolve the betrothal, undo the knot of the engagement. The bizarre nature of the speaker’s plea comes to a climax in the paradoxical final couplet, in which the speaker claims that only if God takes him prisoner can he be free, and only if God ravishes him can he be chaste (pure). The shock of God ravishing reverberates through the whole poem and makes for a much more challenging, and some would say interesting, portrayal of God.

Plosive alliteration ‘batter; breake; blowe; burn’ gives the sense of energy and violence that Donne would like God to employ.

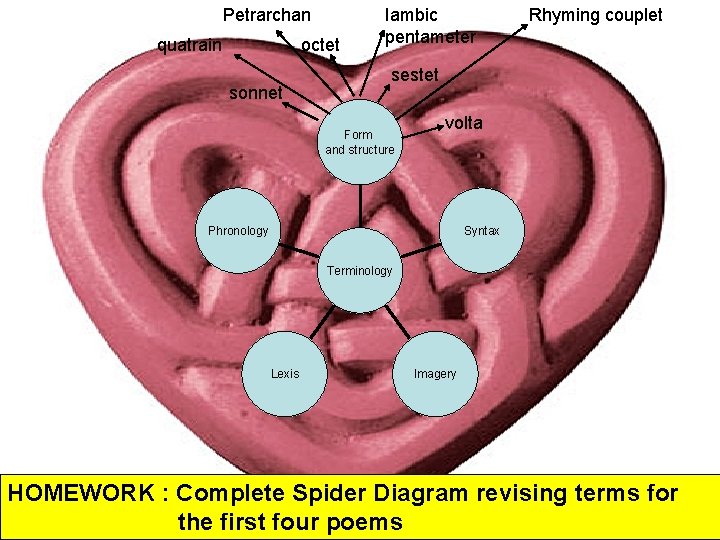

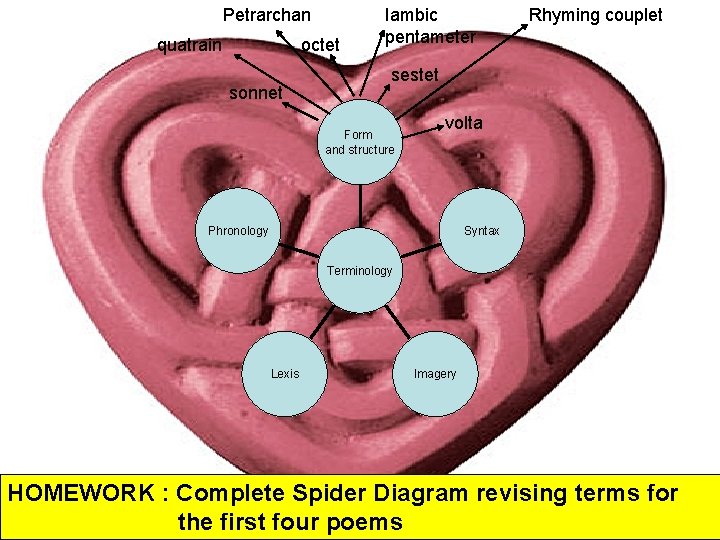

Form and Structure Grammar and Syntax Lexis and Imagery Phonology

Task: Illustrate the two central images of the poem. 1. The speaker as a ‘usurpt town’, overthrown by evil forces, struggling to accept God and let him in. 2. The speaker engaged or belonging to another but still in love with God, wanting to be enthrall[ed] or ‘ravish[ed]’ by God. Use quotes from the poem to annotate your illustration.

Petrarchan quatrain octet sonnet Iambic pentameter Rhyming couplet sestet Form and structure volta Phronology Syntax Terminology Lexis Imagery HOMEWORK : Complete Spider Diagram revising terms for the first four poems