Joan Cahill 1 Sean Wetherall 2 Niall ONeil

- Slides: 1

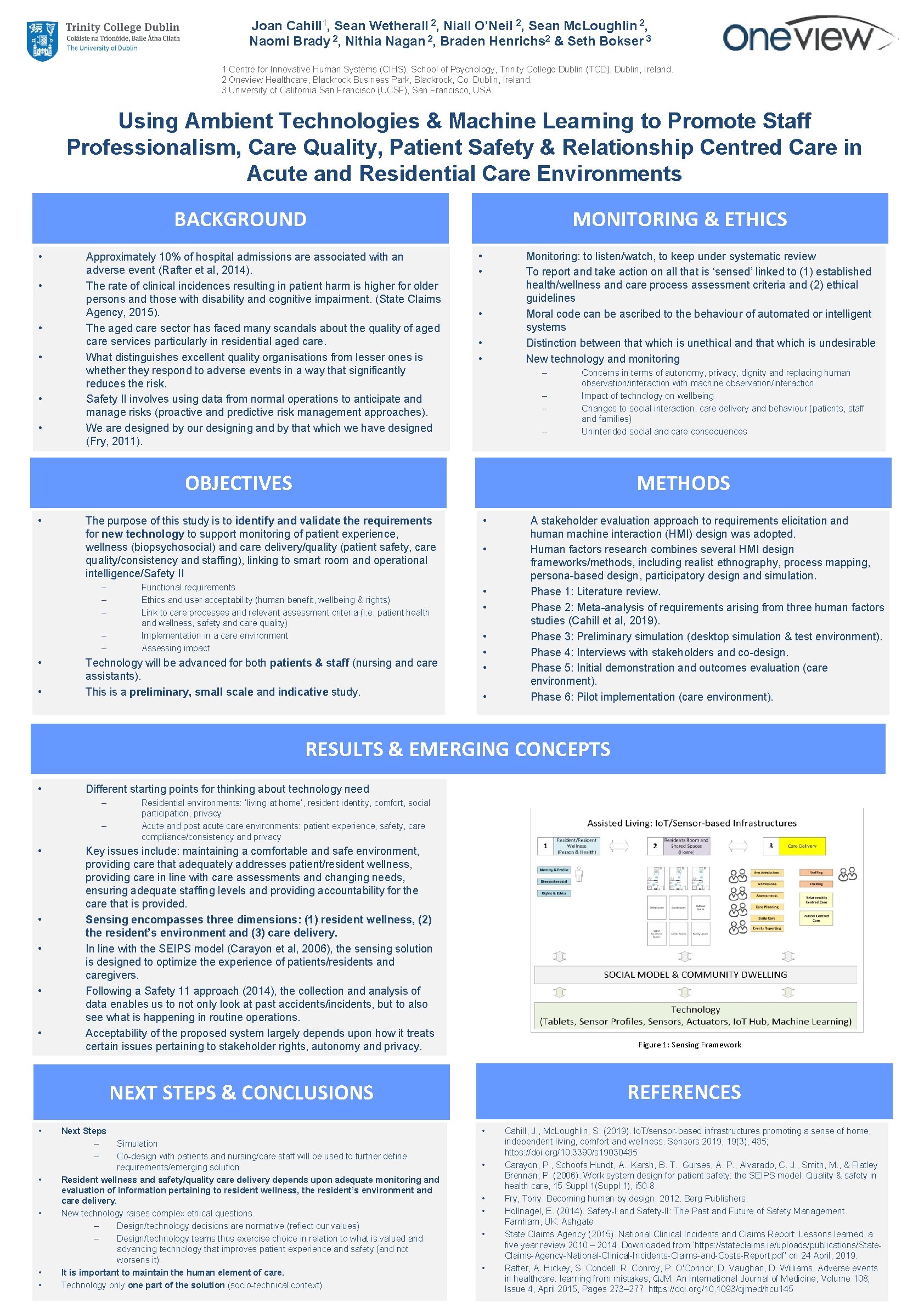

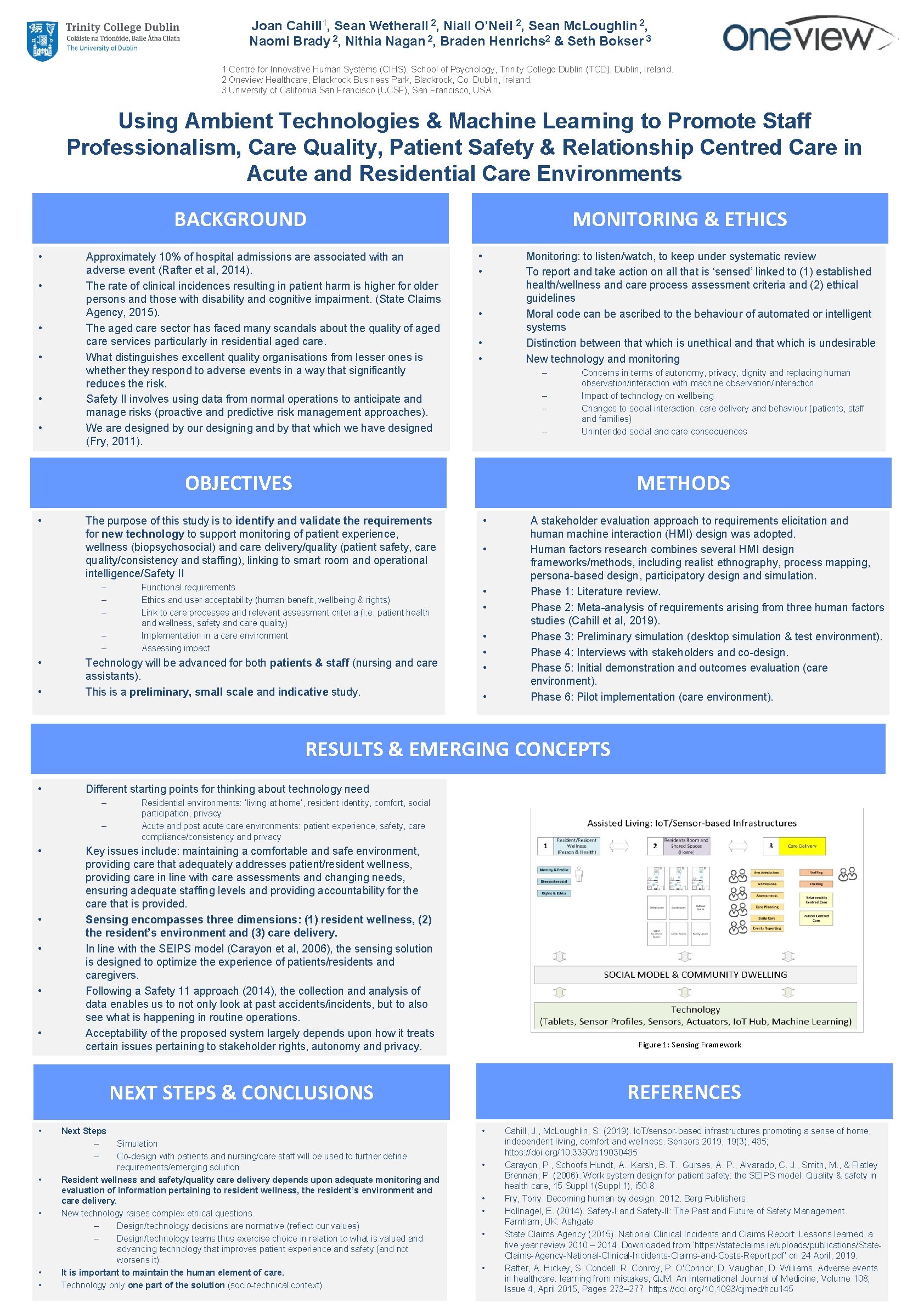

Joan Cahill 1, Sean Wetherall 2, Niall O’Neil 2, Sean Mc. Loughlin 2, Naomi Brady 2, Nithia Nagan 2, Braden Henrichs 2 & Seth Bokser 3 1 Centre for Innovative Human Systems (CIHS), School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin (TCD), Dublin, Ireland. 2 Oneview Healthcare, Blackrock Business Park, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, Ireland. 3 University of California San Francisco (UCSF), San Francisco, USA. Using Ambient Technologies & Machine Learning to Promote Staff Professionalism, Care Quality, Patient Safety & Relationship Centred Care in Acute and Residential Care Environments BACKGROUND • • • Approximately 10% of hospital admissions are associated with an adverse event (Rafter et al, 2014). The rate of clinical incidences resulting in patient harm is higher for older persons and those with disability and cognitive impairment. (State Claims Agency, 2015). The aged care sector has faced many scandals about the quality of aged care services particularly in residential aged care. What distinguishes excellent quality organisations from lesser ones is whether they respond to adverse events in a way that significantly reduces the risk. Safety II involves using data from normal operations to anticipate and manage risks (proactive and predictive risk management approaches). We are designed by our designing and by that which we have designed (Fry, 2011). MONITORING & ETHICS • • Monitoring: to listen/watch, to keep under systematic review To report and take action on all that is ‘sensed’ linked to (1) established health/wellness and care process assessment criteria and (2) ethical guidelines Moral code can be ascribed to the behaviour of automated or intelligent systems Distinction between that which is unethical and that which is undesirable New technology and monitoring • • • – – Concerns in terms of autonomy, privacy, dignity and replacing human observation/interaction with machine observation/interaction Impact of technology on wellbeing Changes to social interaction, care delivery and behaviour (patients, staff and families) Unintended social and care consequences OBJECTIVES • The purpose of this study is to identify and validate the requirements for new technology to support monitoring of patient experience, wellness (biopsychosocial) and care delivery/quality (patient safety, care quality/consistency and staffing), linking to smart room and operational intelligence/Safety II – – – • • METHODS Functional requirements Ethics and user acceptability (human benefit, wellbeing & rights) Link to care processes and relevant assessment criteria (i. e. patient health and wellness, safety and care quality) Implementation in a care environment Assessing impact Technology will be advanced for both patients & staff (nursing and care assistants). This is a preliminary, small scale and indicative study. • • A stakeholder evaluation approach to requirements elicitation and human machine interaction (HMI) design was adopted. Human factors research combines several HMI design frameworks/methods, including realist ethnography, process mapping, persona-based design, participatory design and simulation. Phase 1: Literature review. Phase 2: Meta-analysis of requirements arising from three human factors studies (Cahill et al, 2019). Phase 3: Preliminary simulation (desktop simulation & test environment). Phase 4: Interviews with stakeholders and co-design. Phase 5: Initial demonstration and outcomes evaluation (care environment). Phase 6: Pilot implementation (care environment). RESULTS & EMERGING CONCEPTS • Different starting points for thinking about technology need – – • • • Residential environments: ‘living at home’, residentity, comfort, social participation, privacy Acute and post acute care environments: patient experience, safety, care compliance/consistency and privacy Key issues include: maintaining a comfortable and safe environment, providing care that adequately addresses patient/resident wellness, providing care in line with care assessments and changing needs, ensuring adequate staffing levels and providing accountability for the care that is provided. Sensing encompasses three dimensions: (1) resident wellness, (2) the resident’s environment and (3) care delivery. In line with the SEIPS model (Carayon et al, 2006), the sensing solution is designed to optimize the experience of patients/residents and caregivers. Following a Safety 11 approach (2014), the collection and analysis of data enables us to not only look at past accidents/incidents, but to also see what is happening in routine operations. Acceptability of the proposed system largely depends upon how it treats certain issues pertaining to stakeholder rights, autonomy and privacy. Figure 1: Sensing Framework REFERENCES NEXT STEPS & CONCLUSIONS • • • Next Steps – – Simulation Co-design with patients and nursing/care staff will be used to further define requirements/emerging solution. Resident wellness and safety/quality care delivery depends upon adequate monitoring and evaluation of information pertaining to resident wellness, the resident’s environment and care delivery. New technology raises complex ethical questions. – Design/technology decisions are normative (reflect our values) – Design/technology teams thus exercise choice in relation to what is valued and advancing technology that improves patient experience and safety (and not worsens it). It is important to maintain the human element of care. Technology only one part of the solution (socio-technical context). • • • Cahill, J. , Mc. Loughlin, S. (2019). Io. T/sensor-based infrastructures promoting a sense of home, independent living, comfort and wellness. Sensors 2019, 19(3), 485; https: //doi. org/10. 3390/s 19030485 Carayon, P. , Schoofs Hundt, A. , Karsh, B. T. , Gurses, A. P. , Alvarado, C. J. , Smith, M. , & Flatley Brennan, P. (2006). Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Quality & safety in health care, 15 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), i 50 -8. Fry, Tony. Becoming human by design. 2012. Berg Publishers. Hollnagel, E. (2014). Safety-I and Safety-II: The Past and Future of Safety Management. Farnham, UK: Ashgate. State Claims Agency (2015). National Clinical Incidents and Claims Report: Lessons learned, a five year review 2010 – 2014. Downloaded from ‘https: //stateclaims. ie/uploads/publications/State. Claims-Agency-National-Clinical-Incidents-Claims-and-Costs-Report. pdf’ on 24 April, 2019. Rafter, A. Hickey, S. Condell, R. Conroy, P. O'Connor, D. Vaughan, D. Williams, Adverse events in healthcare: learning from mistakes, QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, Volume 108, Issue 4, April 2015, Pages 273– 277, https: //doi. org/10. 1093/qjmed/hcu 145