JAPANESE INTERNMENT INJUSTICE IN OUR TIME JAPANESE IMMIGRATION

- Slides: 15

JAPANESE INTERNMENT INJUSTICE IN OUR TIME

JAPANESE IMMIGRATION 1877 -1940 ØThe first Japanese immigrant set foot in British Columbia in 1877. His name was Manzo Nagano. ØFrom 1890 until World War I, almost 30, 000 Japanese immigrants entered Canada. The great majority of them settled on the coast of British Columbia. ØFrom the 1920’s to the 1940’s Japanese immigration to Canada dropped considerably. Between 1920 and 1940 approximately 5000 Japanese immigrated into Canada. ØDuring the 1920’s, 30’s and 40’s Canada’s Immigration Act gave the government the right to limit immigration, and deny entry to those nationalities deemed undesirable. Asians were on the list of undesirable immigrants, which explains the drop in Japanese immigrants during these years.

Why were the Japanese undesirable? ØJapanese immigrants tended to pocket themselves into their own communities and did not interact with other nationality groups. They “segregated” themselves. ØDue to their “segregation”, the Japanese did not assimilate into Canadian Society. They kept to their traditions and did not assume Canadian traditions and qualities. This was seen as anti. Canadian activity. ØCanada wanted immigrants who would readily assimilate into Canadian Society: adapt Canadian language, culture, tradition, laws, religion, etc. The Japanese refused to assimilate fully and were thus deemed undesirable.

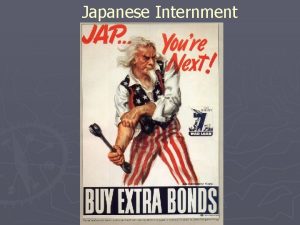

RACISM IN BRITISH COLUMBIA ØSince the late 1850’s the West Coast had been divided by deep racial problems. There was an especially high Anti-Asian sentiment in the West. ØJapanese were segregated: the white population in B. C. would not interact with the Japanese, jobs were denied to Japanese, and they were looked upon with suspicion. ØThe Japanese community was seen with suspicion. They thought the Asians were trying to take over B. C. This fear of Asians in B. C. was known as “Yellow Peril”. This fear prompted anti-Asian sentiments through discrimination, verbal abuse, and even mob violence.

THE “YELLOW PERIL” ØThe population growth in the Japanese communities was far higher than the white communities. This was seen as a threat because as the community kept growing, the more land they inhabited and the more businesses and networks they would open. ØThe Japanese community took over the fishing industry in British Columbia. They were better fishermen and the other communities could not compete with them. This was seen as a take-over ploy. ØJapan’s conquests in Asia sparked fear that British Columbia would be next, due to the large Japanese community living on the coast. They believed that all Japanese living in B. C. had the potential to be spies and were communicating with Japan. ØWith the attack on Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941, fear and Anti-Asian sentiments intensified.

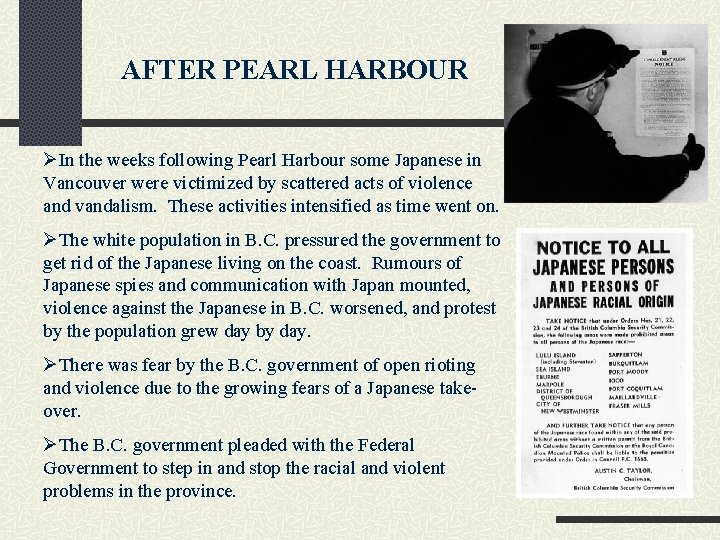

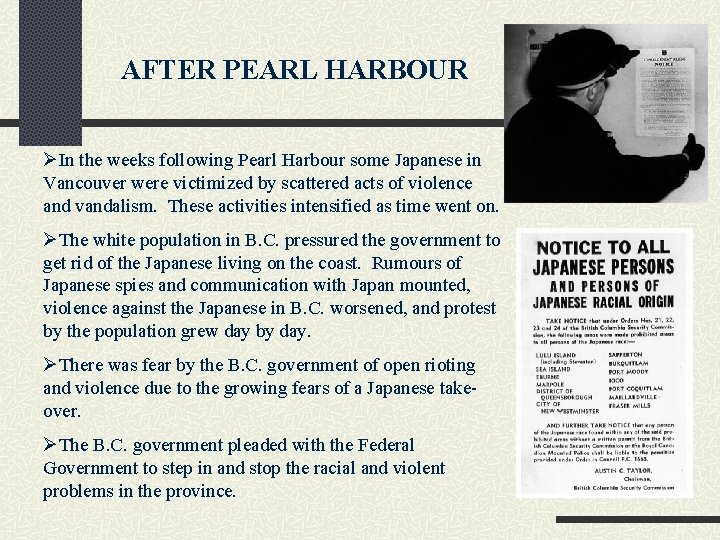

AFTER PEARL HARBOUR ØIn the weeks following Pearl Harbour some Japanese in Vancouver were victimized by scattered acts of violence and vandalism. These activities intensified as time went on. ØThe white population in B. C. pressured the government to get rid of the Japanese living on the coast. Rumours of Japanese spies and communication with Japan mounted, violence against the Japanese in B. C. worsened, and protest by the population grew day by day. ØThere was fear by the B. C. government of open rioting and violence due to the growing fears of a Japanese takeover. ØThe B. C. government pleaded with the Federal Government to step in and stop the racial and violent problems in the province.

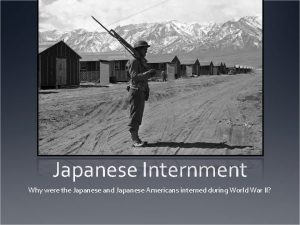

WWII – Japanese Internment Canada declared war on Japan in December 1941. On 25 December 1941, the Japanese forced the surrender of the British garrison at Hong Kong, including two battalions of Canadians. Fears of a Japanese invasion spread along the Pacific Coast.

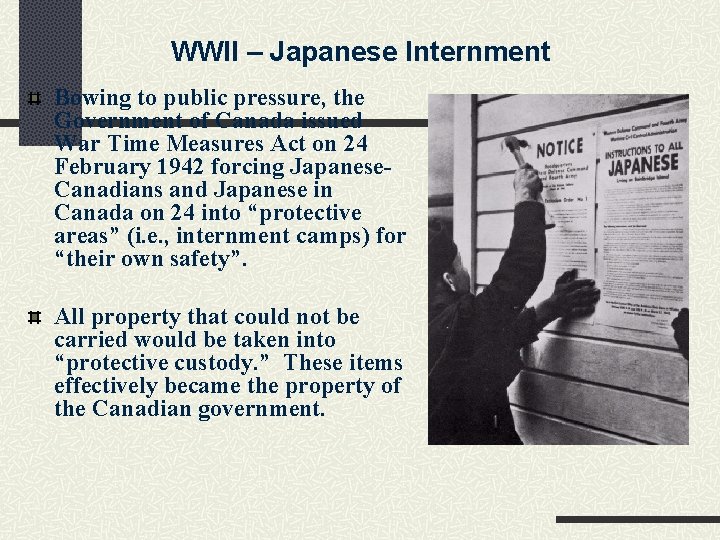

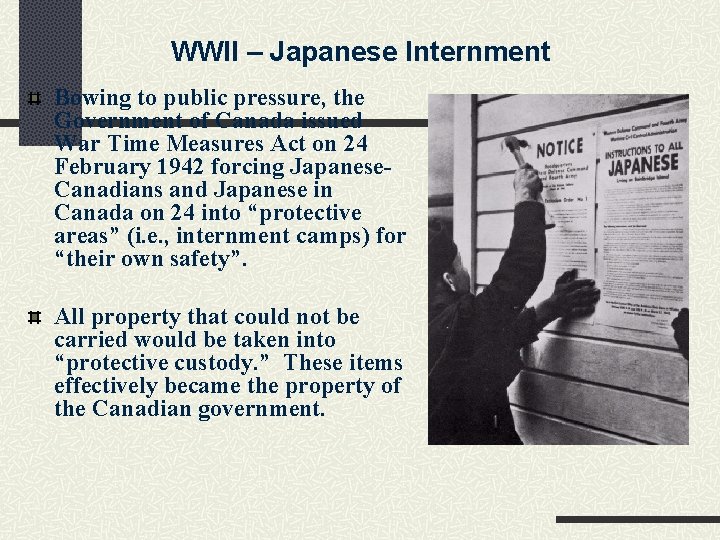

WWII – Japanese Internment Bowing to public pressure, the Government of Canada issued War Time Measures Act on 24 February 1942 forcing Japanese. Canadians and Japanese in Canada on 24 into “protective areas” (i. e. , internment camps) for “their own safety”. All property that could not be carried would be taken into “protective custody. ” These items effectively became the property of the Canadian government.

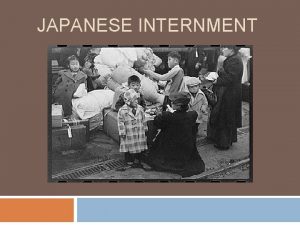

WWII – Japanese Internment In Canada, families were separated. Men were forced into one camp, while women and children entered another camp many kilometres away. Those unwilling to live in internment camps or relocation centres faced the possibility of deportation to Japan. The Japanese did not resist the internment. Their culture emphasized duty and obligation.

WWII – Japanese Internment There were ten internment camps in Canada. The camps included three road camps, two Prisoner of War (POW) camps, and five self- supporting camps scattered throughout Canada. The camps were not surrounded with barbed wire, but living conditions were primitive and crowded with no electricity or running water.

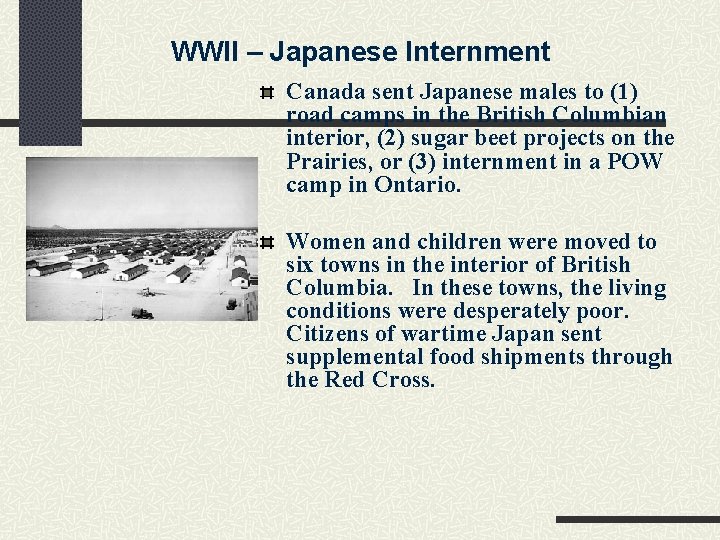

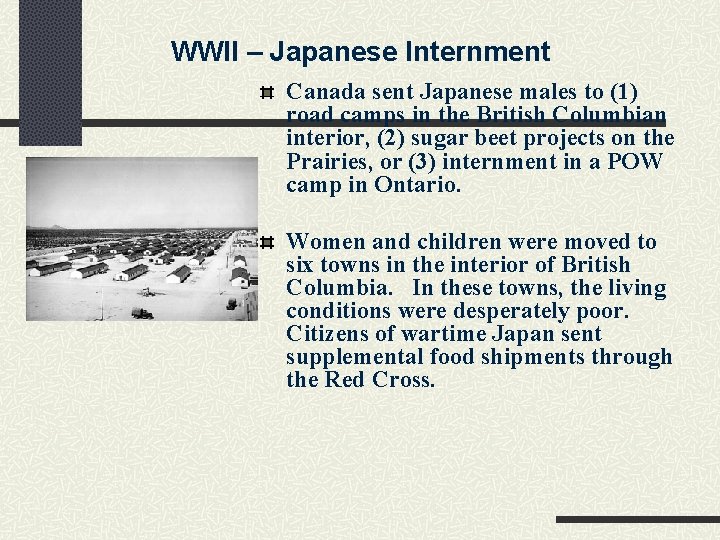

WWII – Japanese Internment Canada sent Japanese males to (1) road camps in the British Columbian interior, (2) sugar beet projects on the Prairies, or (3) internment in a POW camp in Ontario. Women and children were moved to six towns in the interior of British Columbia. In these towns, the living conditions were desperately poor. Citizens of wartime Japan sent supplemental food shipments through the Red Cross.

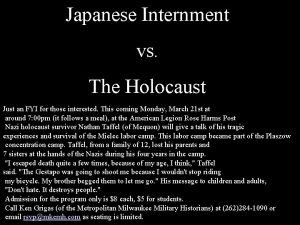

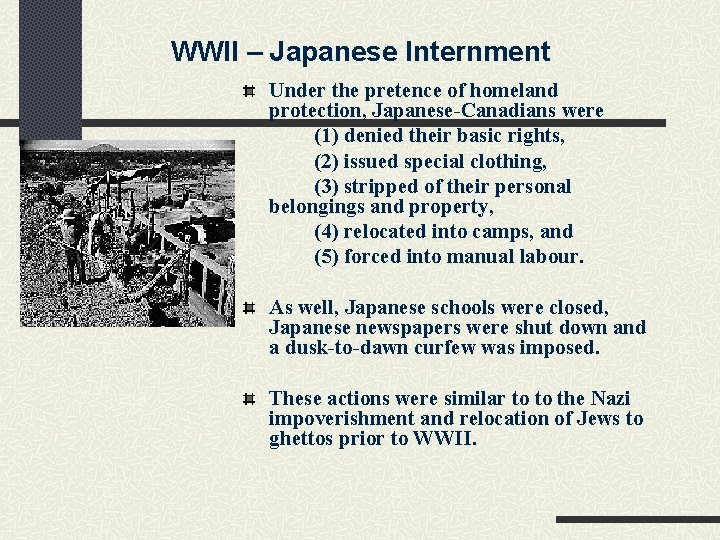

WWII – Japanese Internment Under the pretence of homeland protection, Japanese-Canadians were (1) denied their basic rights, (2) issued special clothing, (3) stripped of their personal belongings and property, (4) relocated into camps, and (5) forced into manual labour. As well, Japanese schools were closed, Japanese newspapers were shut down and a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed. These actions were similar to to the Nazi impoverishment and relocation of Jews to ghettos prior to WWII.

WWII – Japanese Internment After WWII, Canada ordered all Japanese and Japanese-Canadians be deported to Japan. The Supreme Court of Canada supported the law…although some judges ruled women and children were not threats to national security. In 1947, the deportation order was repealed In total, 3, 964 Japanese and Japanese-Canadians were deported.

WWII – Japanese Internment Japanese-Canadians who remained in Canada were not allowed to resettle in British Columbia. Rather, they were ordered to disperse eastward. Their homes and property was not returned. These items had been sold long ago by the Government of Canada. The Japanese did not receive compensation for the sale of their properties. Japanese-Canadians were given the right to vote in 1949.

WWII – Japanese Internment On 22 September 1988, Canadian Prime Minister Brian Mulroney offered a formal apology from Canada to the internees. The Canadian government also provided compensation. The package included (1) $21, 000 to all surviving internees, and (2) the reinstatement of Canadian citizenship to those who were deported to Japan.

I am an american japanese internment

I am an american japanese internment Japanese internment haiku poems

Japanese internment haiku poems Internment by juliet s kono

Internment by juliet s kono September 3, 1939

September 3, 1939 Government newsreel date

Government newsreel date Concentration camps vs internment camps venn diagram

Concentration camps vs internment camps venn diagram Environmental injustice definition ap human geography

Environmental injustice definition ap human geography Résumé de la nouvelle la ficelle

Résumé de la nouvelle la ficelle Injustice theme statement

Injustice theme statement Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere essay

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere essay Fusha e futbollit vizatim

Fusha e futbollit vizatim After death in hinduism

After death in hinduism Start time, end time and elapsed time

Start time, end time and elapsed time Thinking affects our language, which then affects our:

Thinking affects our language, which then affects our: Our census our future

Our census our future Longing for peace our world is troubled

Longing for peace our world is troubled