Iterators CS 101 2012 1 Chakrabarti What is

Iterators CS 101 2012. 1 Chakrabarti

What is an iterator? § Thus far, the only data structure over which we have iterated was the array for (int ix = 0; ix < arr. size(); ++ix) { … arr[ix] … // access as lhs or rhs } § In general there may not be such a simple notion of a single index; e. g. , iterate over: § All dim val map entries in sparse array § All permutations of n items § All non-attacking n-queen positions on an n by n chessboard Chakrabarti

Iterator as an abstraction § We initialize an iterator § Given any state of the iterator, we can ask if there is a next state or we have run out § If there is a next state, we can move the iterator from the current to the next state § We can fetch or modify data associated with the current state of the iterator Chakrabarti

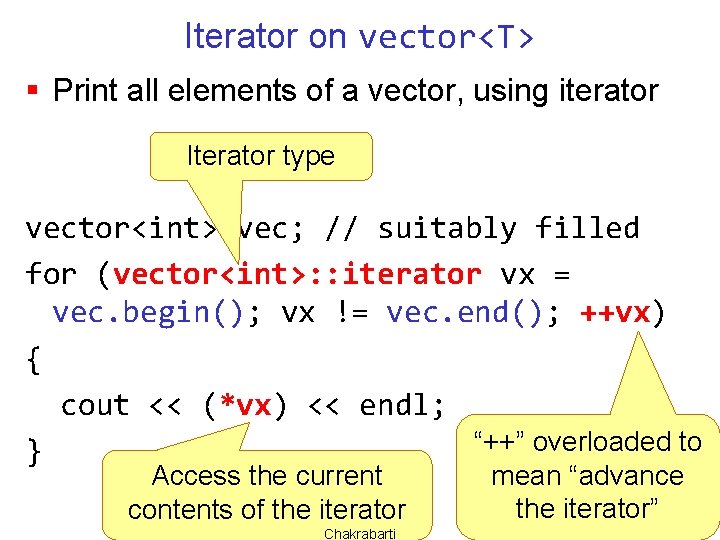

Iterator on vector<T> § Print all elements of a vector, using iterator Iterator type vector<int> vec; // suitably filled for (vector<int>: : iterator vx = vec. begin(); vx != vec. end(); ++vx) { cout << (*vx) << endl; “++” overloaded to } Access the current contents of the iterator Chakrabarti mean “advance the iterator”

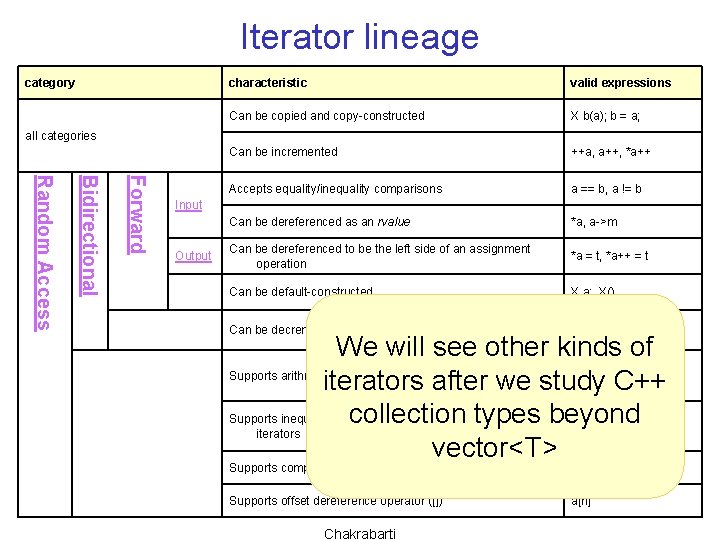

Iterator lineage category characteristic valid expressions Can be copied and copy-constructed X b(a); b = a; Can be incremented ++a, a++, *a++ Accepts equality/inequality comparisons a == b, a != b Can be dereferenced as an rvalue *a, a->m Can be dereferenced to be the left side of an assignment operation *a = t, *a++ = t Can be default-constructed X a; , X() Can be decremented --a, a-- *a-- Supports compound assignment operations += and -= a += n, a -= n Supports offset dereference operator ([]) a[n] all categories Forward Bidirectional Random Access Input Output We will see other kinds of a + n, n + a, Supports arithmetic operators + and n, a – b iterators after we studya –C++ Supports inequality comparisons (<, >, <= andtypes >=) between beyond a < b, a > b collection iterators a <= b, a >= b vector<T> Chakrabarti

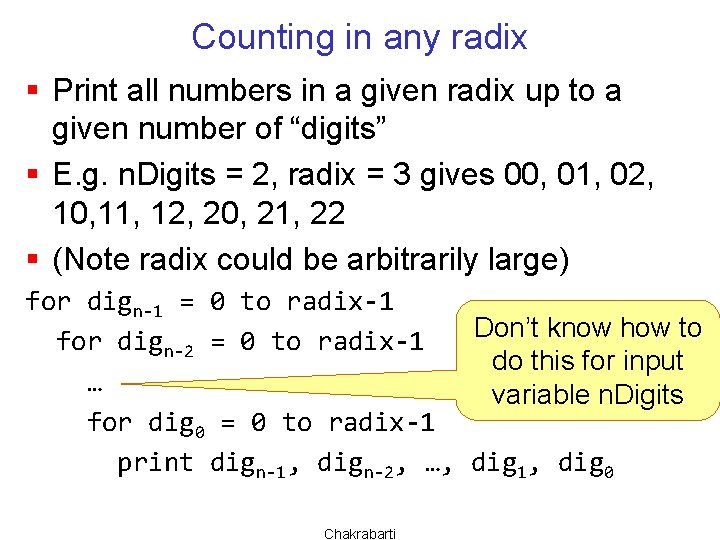

Counting in any radix § Print all numbers in a given radix up to a given number of “digits” § E. g. n. Digits = 2, radix = 3 gives 00, 01, 02, 10, 11, 12, 20, 21, 22 § (Note radix could be arbitrarily large) for dign-1 = 0 to radix-1 Don’t know how to for dign-2 = 0 to radix-1 do this for input … variable n. Digits for dig 0 = 0 to radix-1 print dign-1, dign-2, …, dig 1, dig 0 Chakrabarti

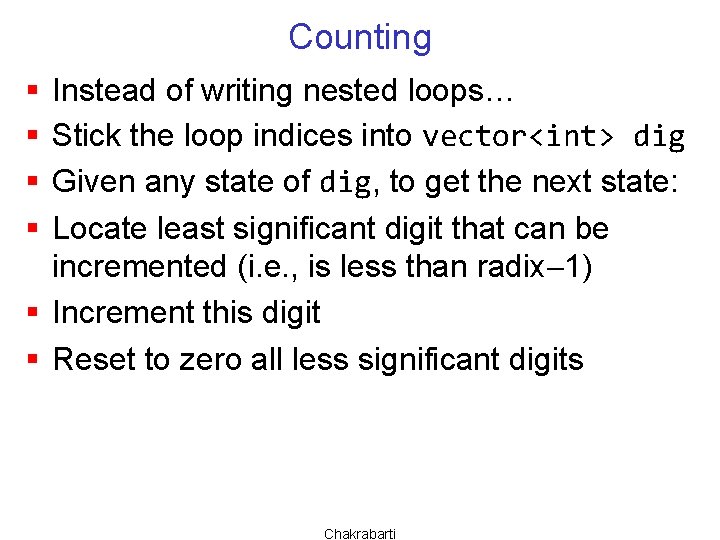

Counting § § Instead of writing nested loops… Stick the loop indices into vector<int> dig Given any state of dig, to get the next state: Locate least significant digit that can be incremented (i. e. , is less than radix 1) § Increment this digit § Reset to zero all less significant digits Chakrabarti

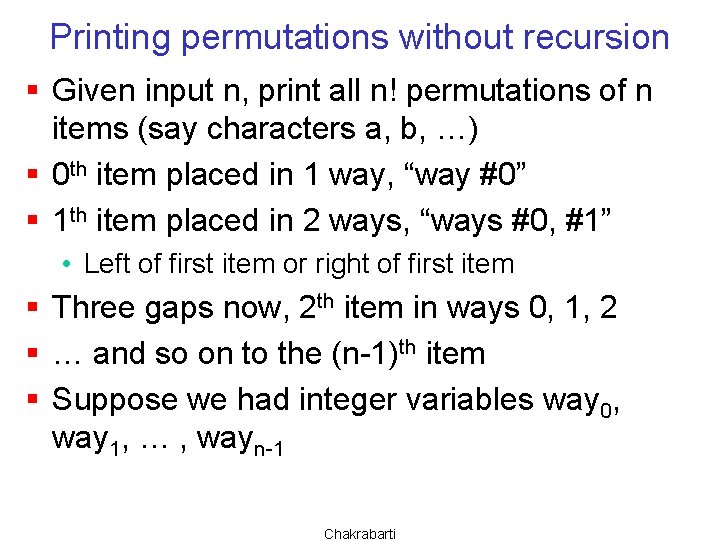

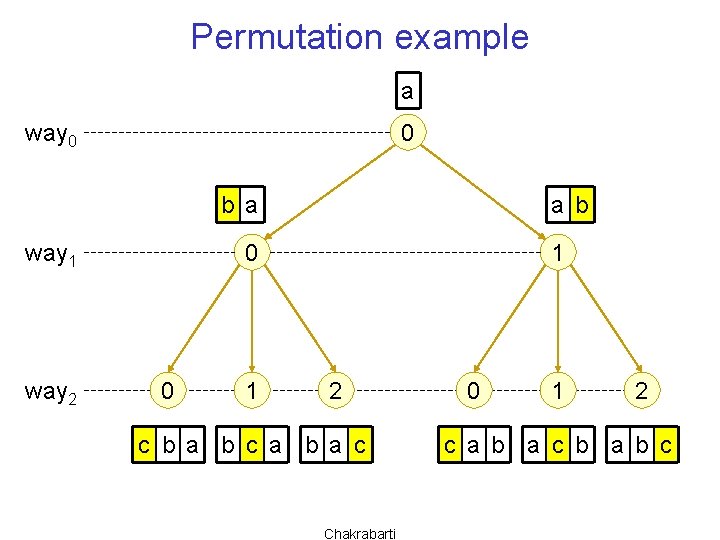

Printing permutations without recursion § Given input n, print all n! permutations of n items (say characters a, b, …) § 0 th item placed in 1 way, “way #0” § 1 th item placed in 2 ways, “ways #0, #1” • Left of first item or right of first item § Three gaps now, 2 th item in ways 0, 1, 2 § … and so on to the (n-1)th item § Suppose we had integer variables way 0, way 1, … , wayn-1 Chakrabarti

Permutation example a way 0 0 b a way 1 way 2 a b 0 0 1 1 2 c b a b c a b a c Chakrabarti 0 1 2 c a b a c b a b c

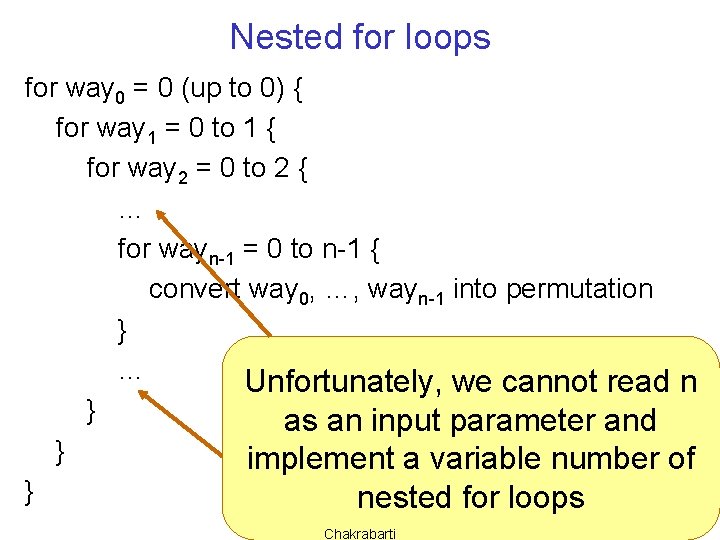

Nested for loops for way 0 = 0 (up to 0) { for way 1 = 0 to 1 { for way 2 = 0 to 2 { … for wayn-1 = 0 to n-1 { convert way 0, …, wayn-1 into permutation } … Unfortunately, we cannot read n } as an input parameter and } implement a variable number of } nested for loops Chakrabarti

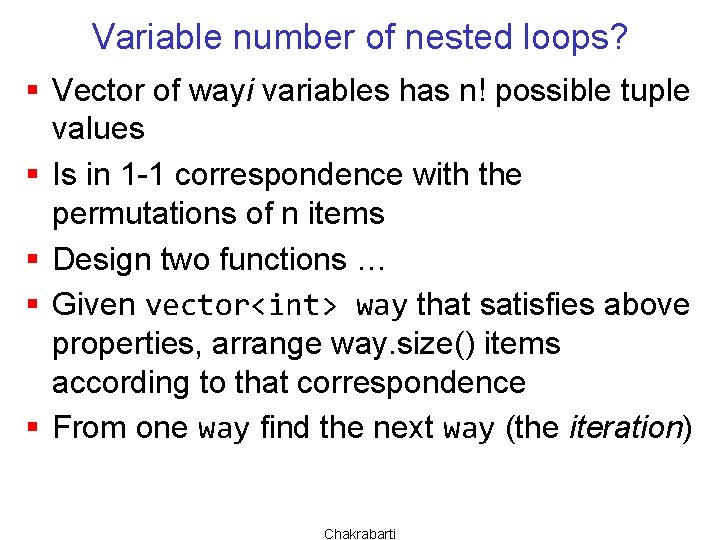

Variable number of nested loops? § Vector of wayi variables has n! possible tuple values § Is in 1 -1 correspondence with the permutations of n items § Design two functions … § Given vector<int> way that satisfies above properties, arrange way. size() items according to that correspondence § From one way find the next way (the iteration) Chakrabarti

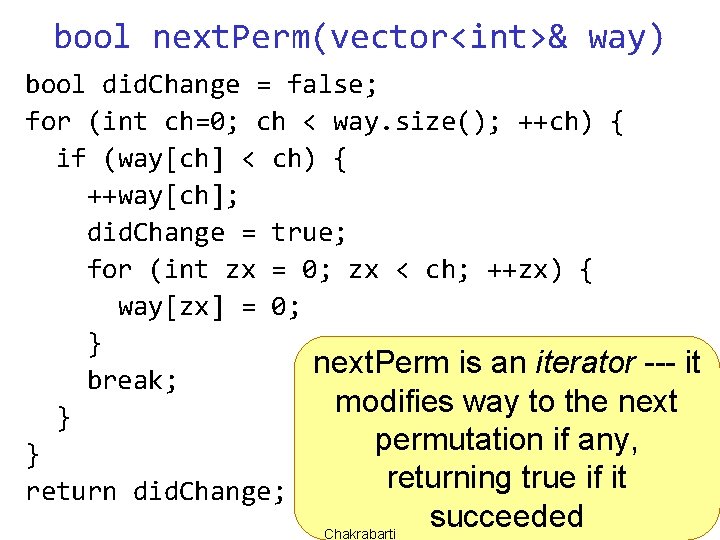

bool next. Perm(vector<int>& way) bool did. Change = false; for (int ch=0; ch < way. size(); ++ch) { if (way[ch] < ch) { ++way[ch]; did. Change = true; for (int zx = 0; zx < ch; ++zx) { way[zx] = 0; } next. Perm is an iterator --it break; modifies way to the next } permutation if any, } returning true if it return did. Change; Chakrabarti succeeded

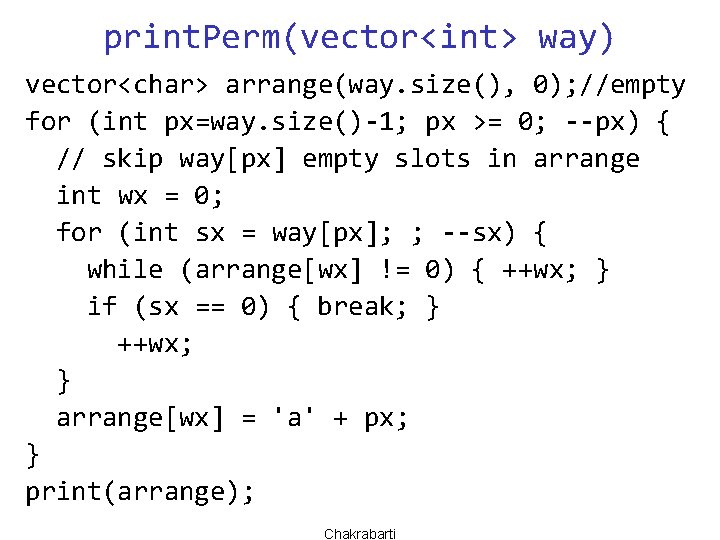

print. Perm(vector<int> way) vector<char> arrange(way. size(), 0); //empty for (int px=way. size()-1; px >= 0; --px) { // skip way[px] empty slots in arrange int wx = 0; for (int sx = way[px]; ; --sx) { while (arrange[wx] != 0) { ++wx; } if (sx == 0) { break; } ++wx; } arrange[wx] = 'a' + px; } print(arrange); Chakrabarti

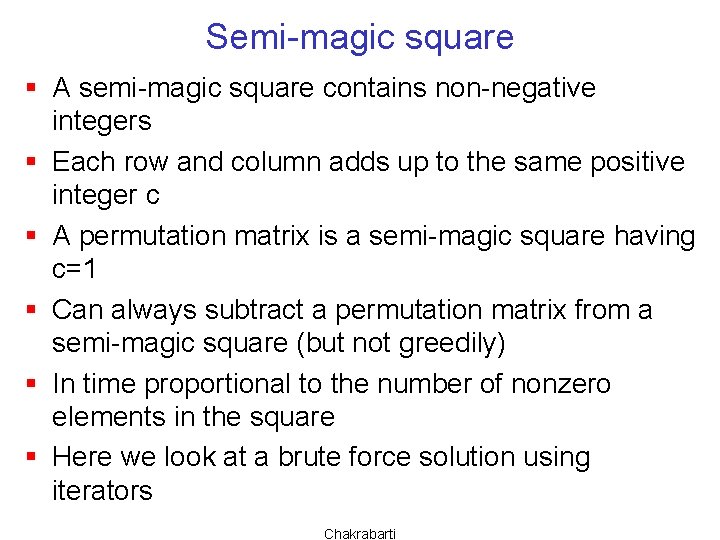

Semi-magic square § A semi-magic square contains non-negative integers § Each row and column adds up to the same positive integer c § A permutation matrix is a semi-magic square having c=1 § Can always subtract a permutation matrix from a semi-magic square (but not greedily) § In time proportional to the number of nonzero elements in the square § Here we look at a brute force solution using iterators Chakrabarti

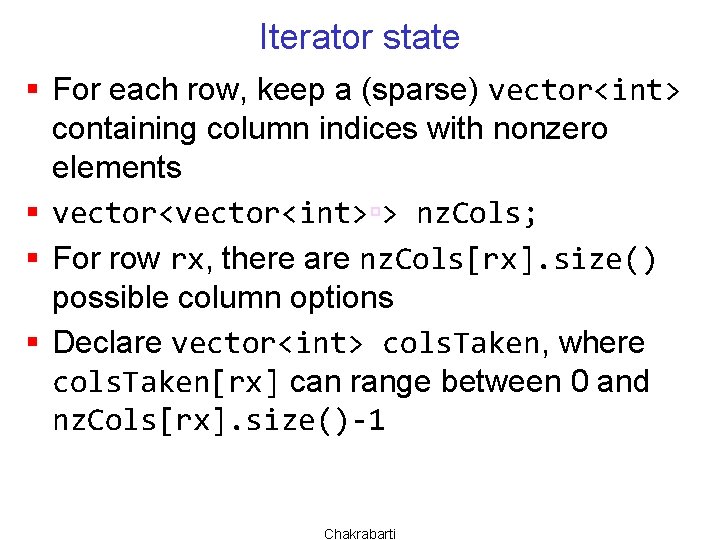

Iterator state § For each row, keep a (sparse) vector<int> containing column indices with nonzero elements § vector<int> > nz. Cols; § For row rx, there are nz. Cols[rx]. size() possible column options § Declare vector<int> cols. Taken, where cols. Taken[rx] can range between 0 and nz. Cols[rx]. size()-1 Chakrabarti

![Nested loop way of thinking for cols. Taken[0] = 0 … nz. Cols[0]. size()-1 Nested loop way of thinking for cols. Taken[0] = 0 … nz. Cols[0]. size()-1](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/e00f764031a03d8be365a5641046e08a/image-16.jpg)

Nested loop way of thinking for cols. Taken[0] = 0 … nz. Cols[0]. size()-1 { for cols. Taken[1] = 0 … nz. Cols[1]. size()-1 { … … … for cols. Taken[n-1] = 0 … nz. Cols[n-1]. size()-1 { check if cols. Taken[0…n-1] define a permutation matrix if so { subtract from magic; update nz. Cols; return } } // end of cols. Taken[n-1] loop … … … } // end of cols. Taken[1] loop Can easily turn } // end of cols. Taken[0] loop into iterator style Chakrabarti

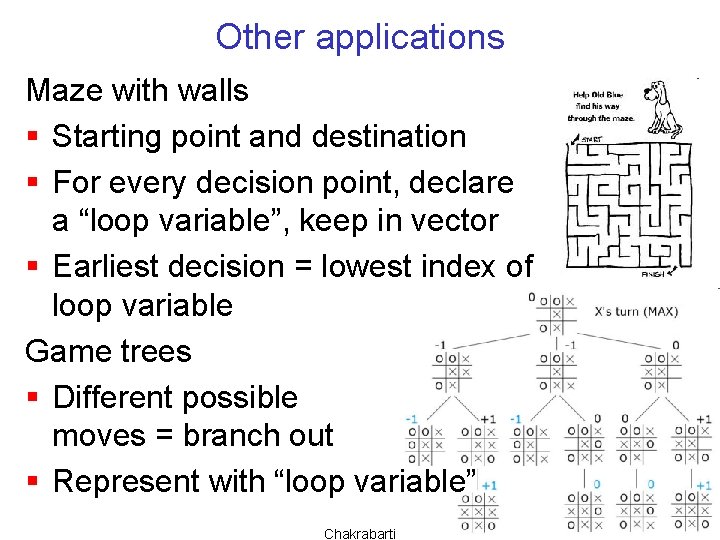

Other applications Maze with walls § Starting point and destination § For every decision point, declare a “loop variable”, keep in vector § Earliest decision = lowest index of loop variable Game trees § Different possible moves = branch out § Represent with “loop variable” Chakrabarti

- Slides: 17