IT 251 Computer Organization and Architecture Optimization and

![Reason #2: Overhead void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { cpu_num Reason #2: Overhead void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { cpu_num](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/4c2e46c0001a571f8dd5864fbb9de5eb/image-29.jpg)

- Slides: 42

IT 251 Computer Organization and Architecture Optimization and Parallelism Modified by R. Helps from original notes by Chia-Chi Teng

Pipelining vs. Parallel processing § In both cases, multiple “things” processed by multiple “functional units” Pipelining: each thing is broken into a sequence of pieces, where each piece is handled by a different (specialized) functional unit Parallel processing: each thing is processed entirely by a single functional unit § We will briefly introduce the key ideas behind parallel processing — instruction level parallelism — thread-level parallelism 2

Paralleism depends on scale § § Multiple computers working in concert — Modern supercomputers — “Beowulf” architecture — Multiple network paths — Chunk size is a complete program module — Capstone project to use idle cycle on campus (install virtual machine) — SETI @ home and offspring Parallelism within a computer: Multiple cores — Chunk size is a subroutine or small app Parallelism within a computer: single core — Multiple execution units within core — Chunk size is on the instruction level Parallelism in GPU — Optimized for many similar math operations • Linear algebra and DSP — Chunk size is a math operation 3

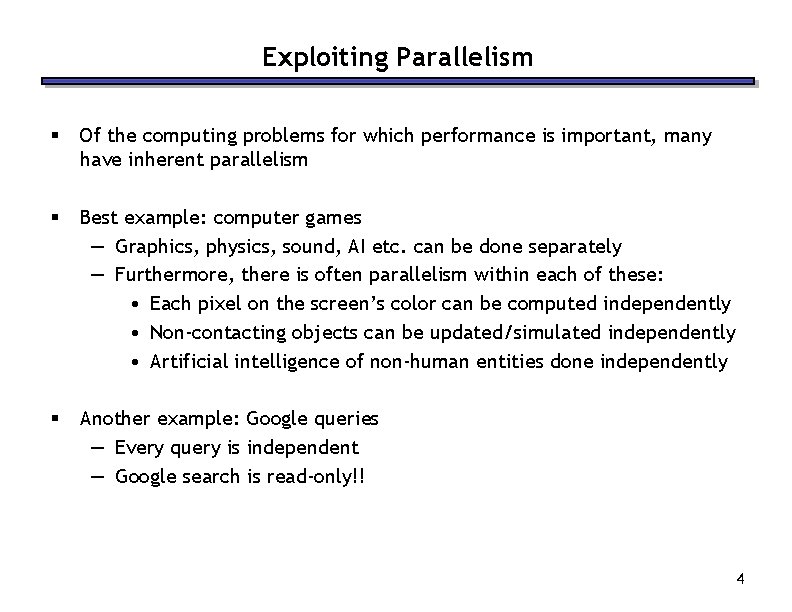

Exploiting Parallelism § Of the computing problems for which performance is important, many have inherent parallelism § Best example: computer games — Graphics, physics, sound, AI etc. can be done separately — Furthermore, there is often parallelism within each of these: • Each pixel on the screen’s color can be computed independently • Non-contacting objects can be updated/simulated independently • Artificial intelligence of non-human entities done independently § Another example: Google queries — Every query is independent — Google search is read-only!! 4

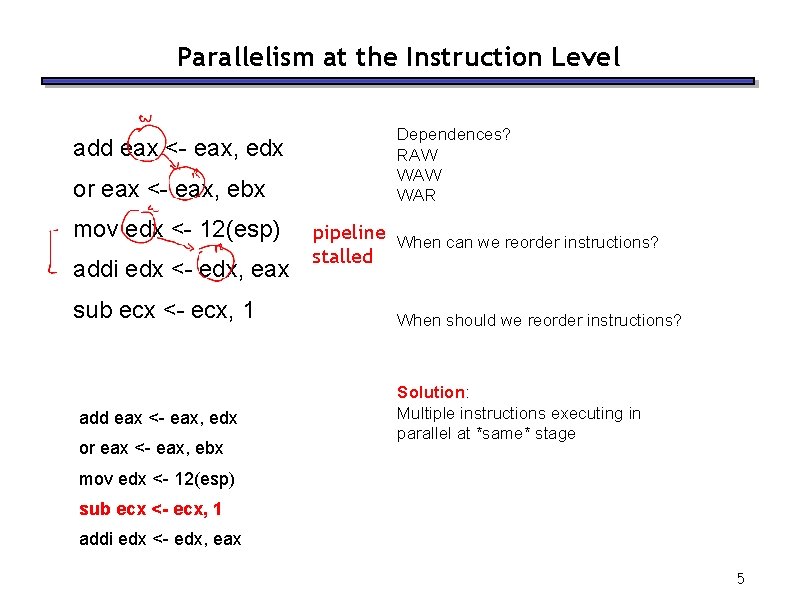

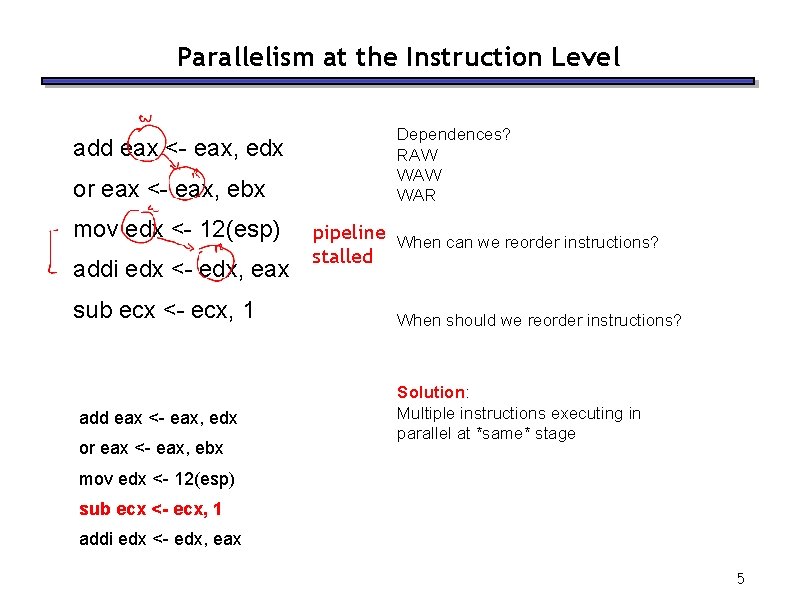

Parallelism at the Instruction Level add eax <- eax, edx or eax <- eax, ebx mov edx <- 12(esp) addi edx <- edx, eax sub ecx <- ecx, 1 add eax <- eax, edx or eax <- eax, ebx Dependences? RAW WAR pipeline When can we reorder instructions? stalled When should we reorder instructions? Solution: Multiple instructions executing in parallel at *same* stage mov edx <- 12(esp) sub ecx <- ecx, 1 addi edx <- edx, eax 5

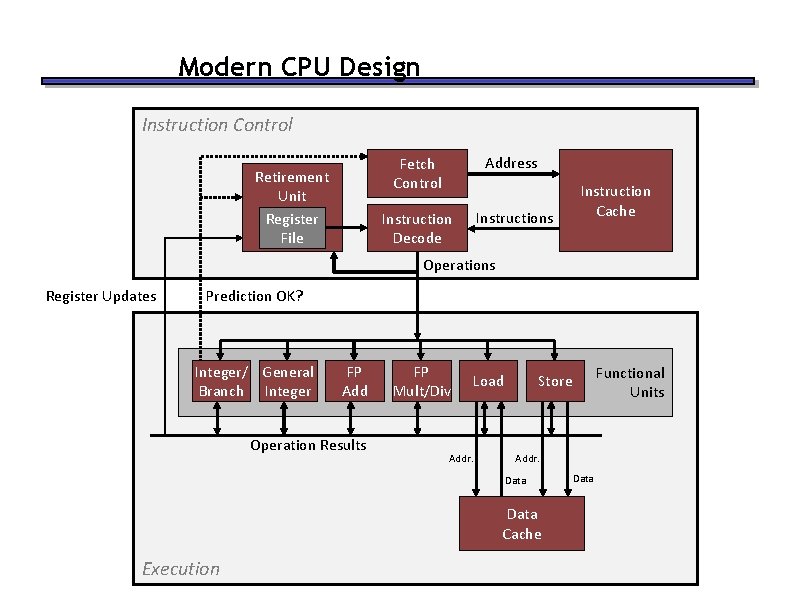

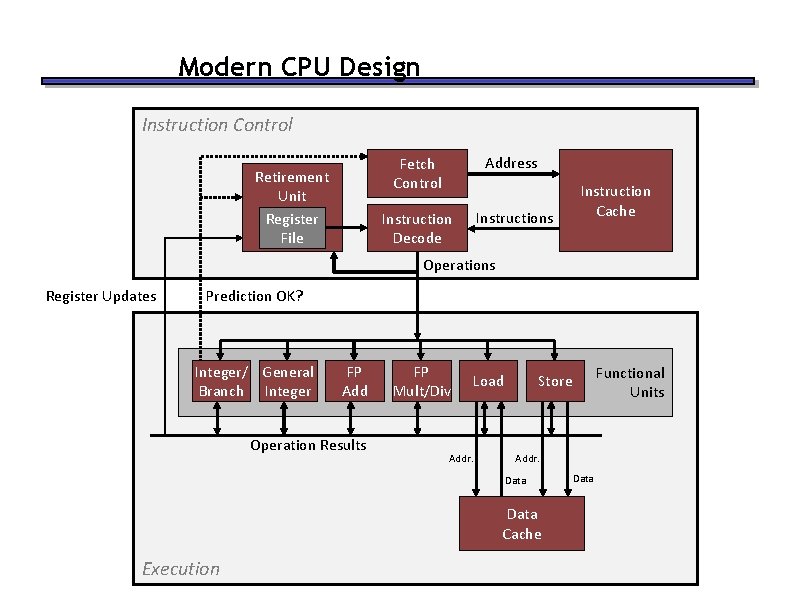

Modern CPU Design Instruction Control Retirement Unit Register File Fetch Control Address Instruction Decode Instructions Instruction Cache Operations Register Updates Prediction OK? Integer/ General Branch Integer FP Add Operation Results FP Mult/Div Load Addr. Data Cache Execution Functional Units Store Data

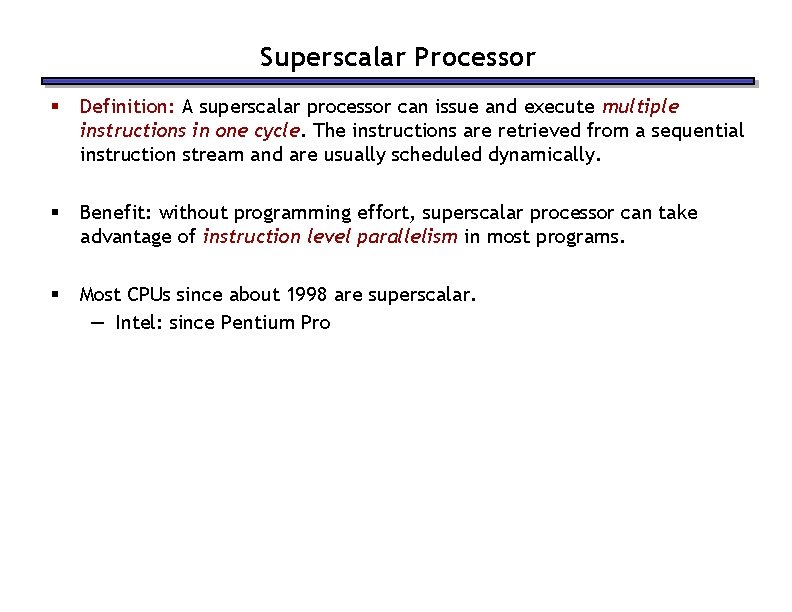

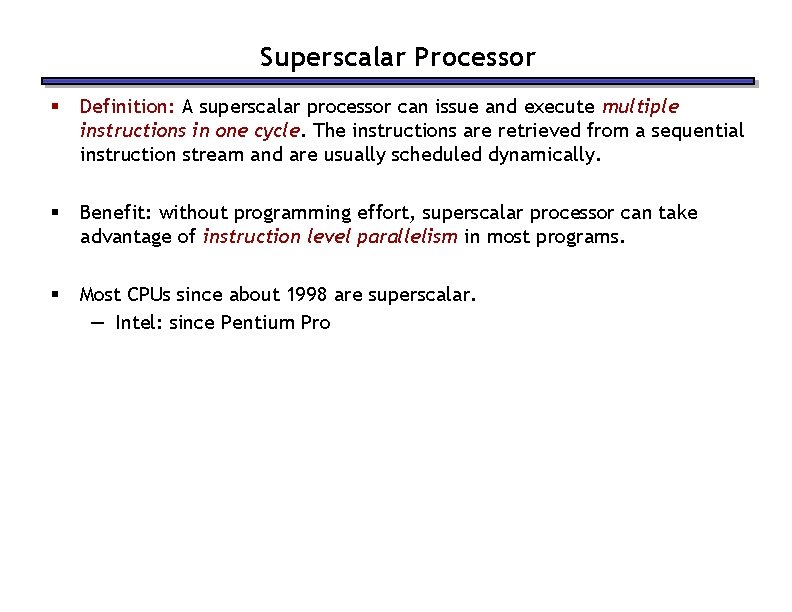

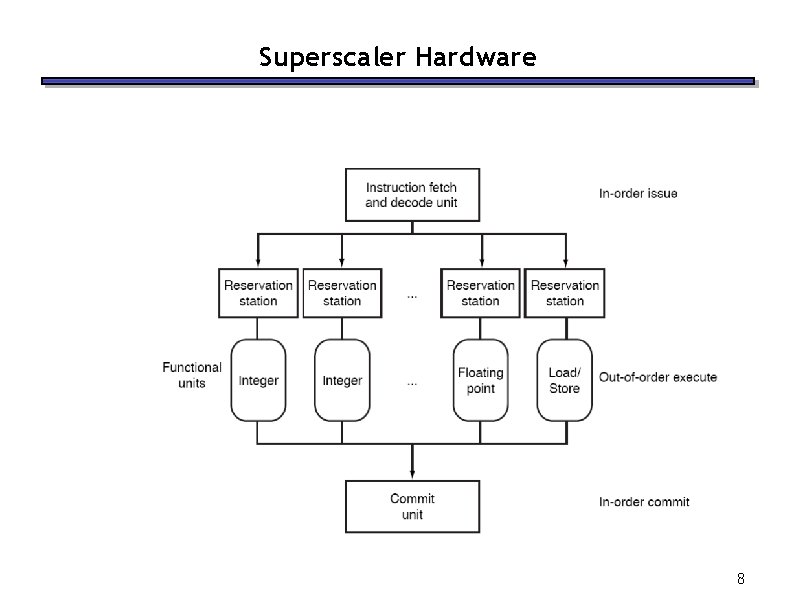

Superscalar Processor § Definition: A superscalar processor can issue and execute multiple instructions in one cycle. The instructions are retrieved from a sequential instruction stream and are usually scheduled dynamically. § Benefit: without programming effort, superscalar processor can take advantage of instruction level parallelism in most programs. § Most CPUs since about 1998 are superscalar. — Intel: since Pentium Pro

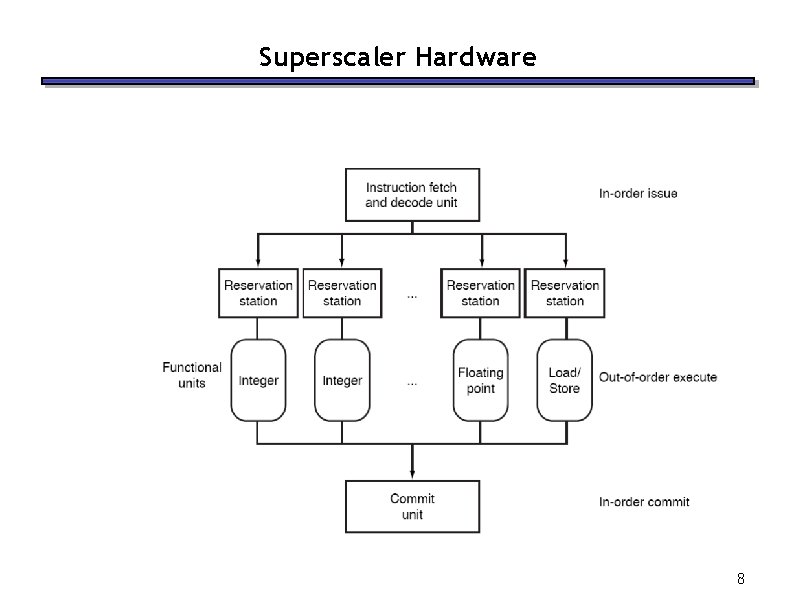

Superscaler Hardware 8

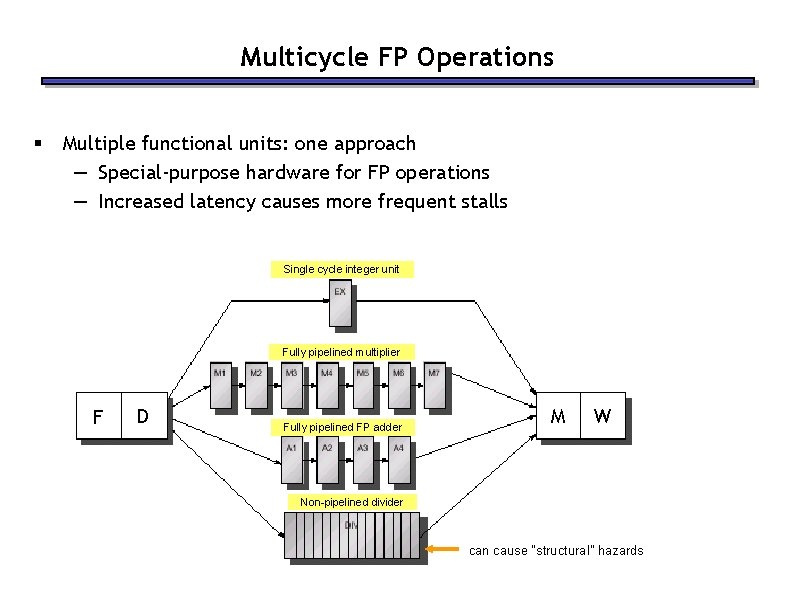

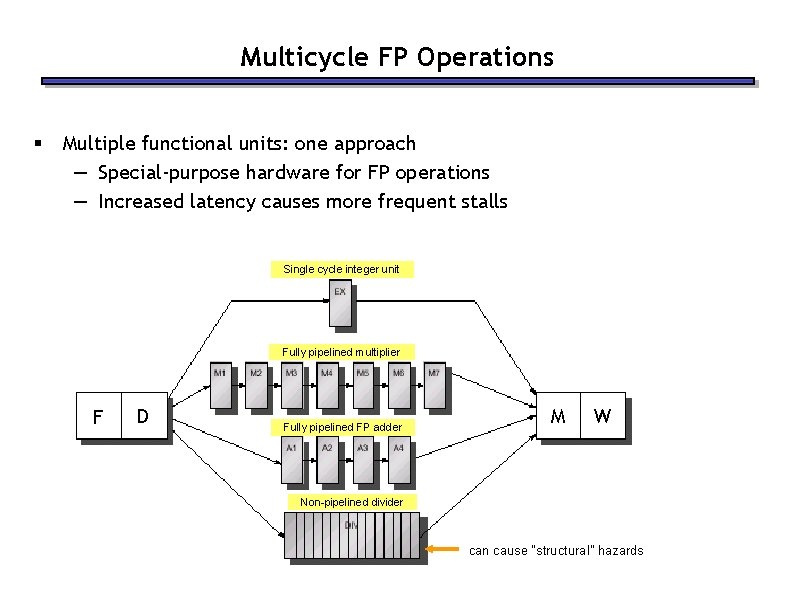

Multicycle FP Operations § Multiple functional units: one approach — Special-purpose hardware for FP operations — Increased latency causes more frequent stalls Single cycle integer unit Fully pipelined multiplier F D Fully pipelined FP adder M W Non-pipelined divider can cause “structural” hazards

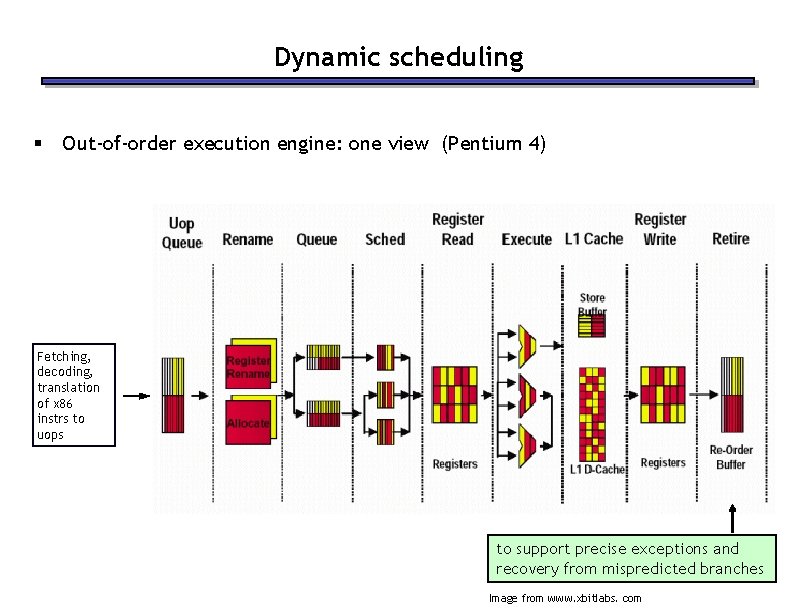

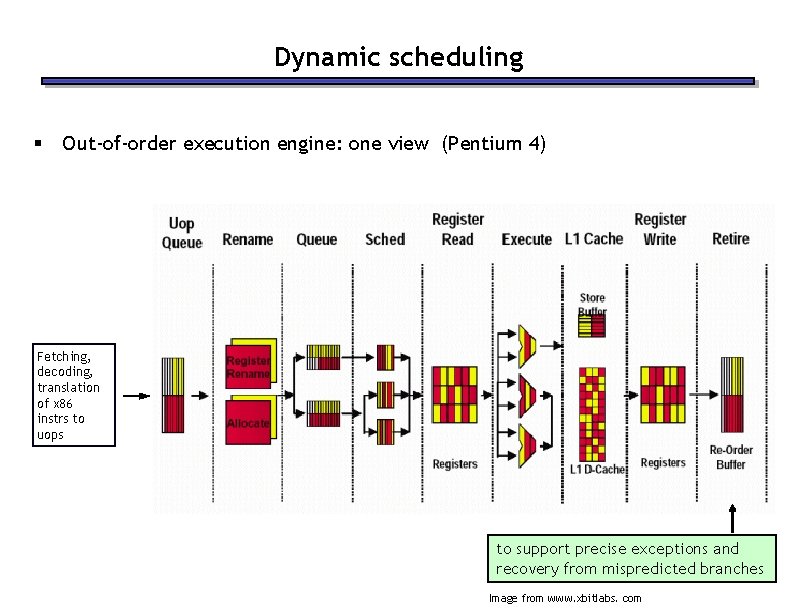

Dynamic scheduling § Out-of-order execution engine: one view (Pentium 4) Fetching, decoding, translation of x 86 instrs to uops to support precise exceptions and recovery from mispredicted branches Image from www. xbitlabs. com

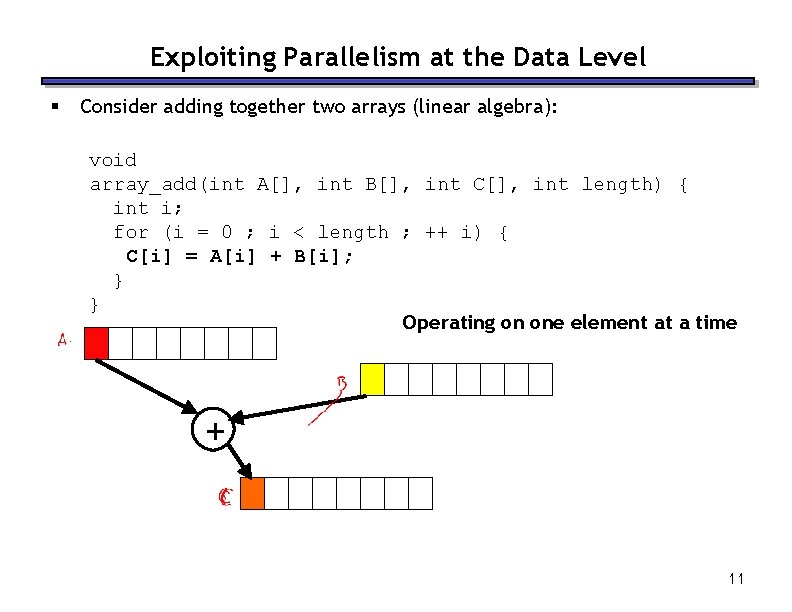

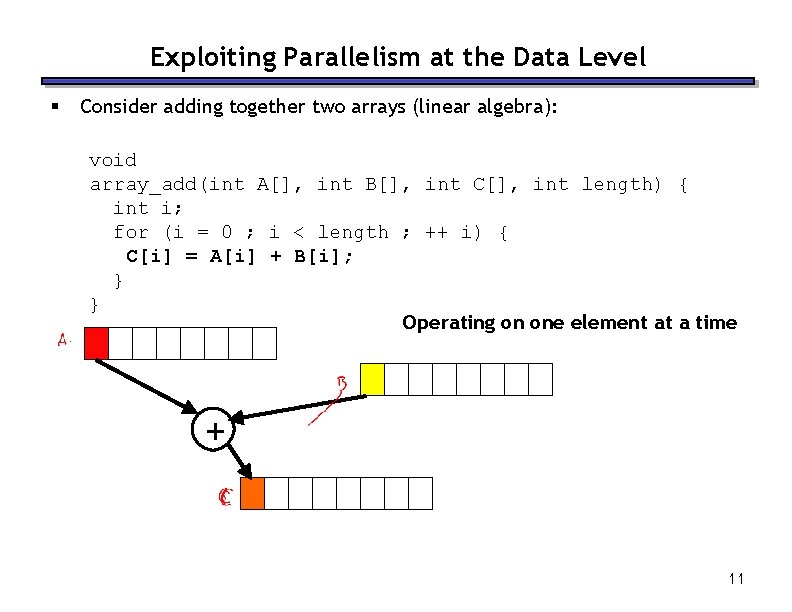

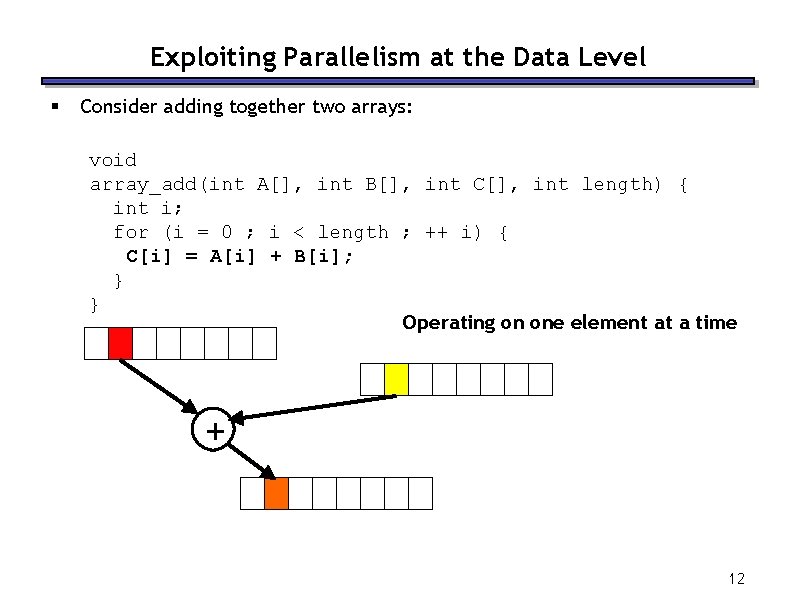

Exploiting Parallelism at the Data Level § Consider adding together two arrays (linear algebra): void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { int i; for (i = 0 ; i < length ; ++ i) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } } Operating on one element at a time + 11

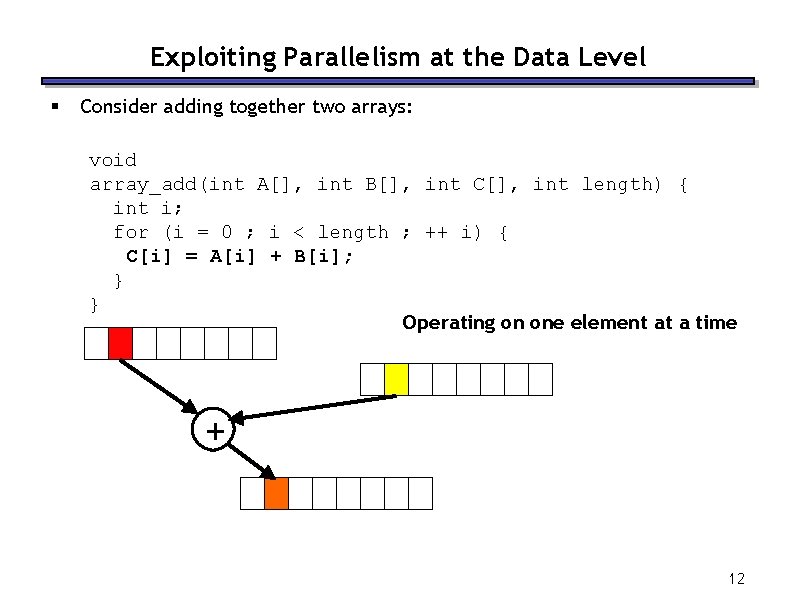

Exploiting Parallelism at the Data Level § Consider adding together two arrays: void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { int i; for (i = 0 ; i < length ; ++ i) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } } Operating on one element at a time + 12

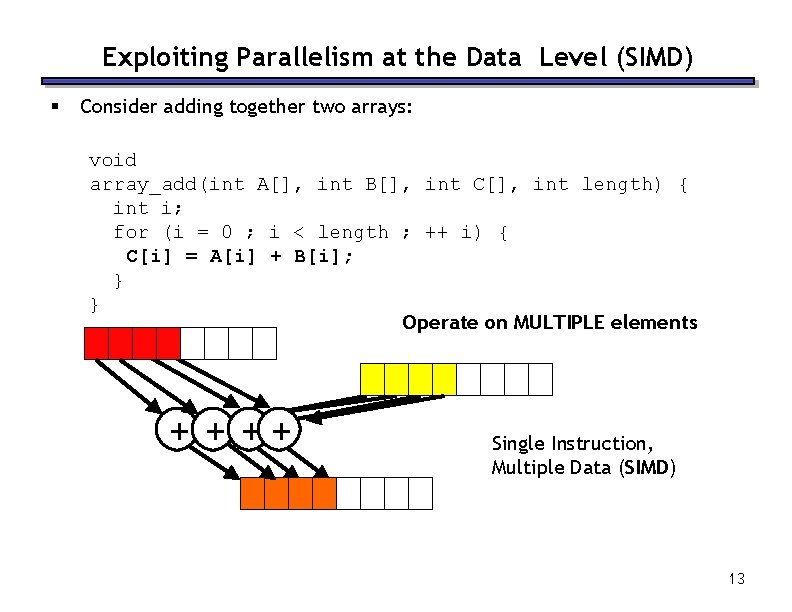

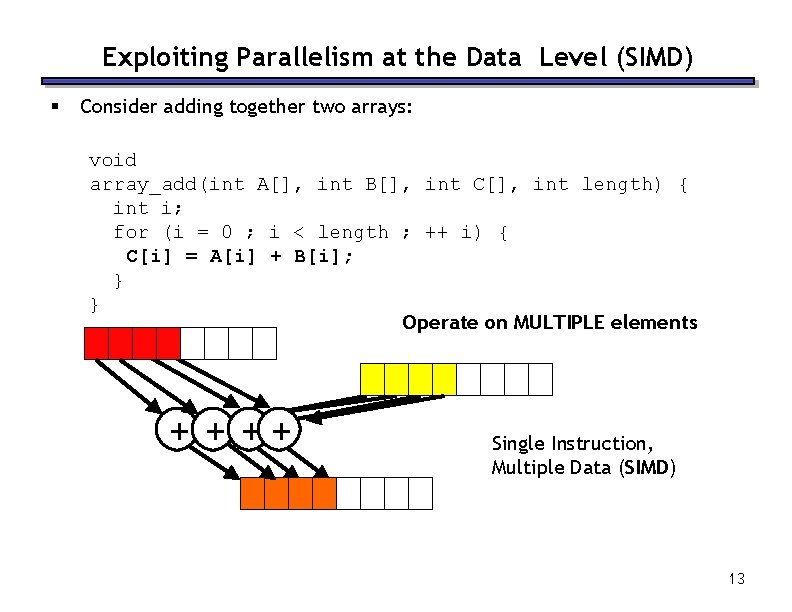

Exploiting Parallelism at the Data Level (SIMD) § Consider adding together two arrays: void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { int i; for (i = 0 ; i < length ; ++ i) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } } Operate on MULTIPLE elements + + ++ Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) 13

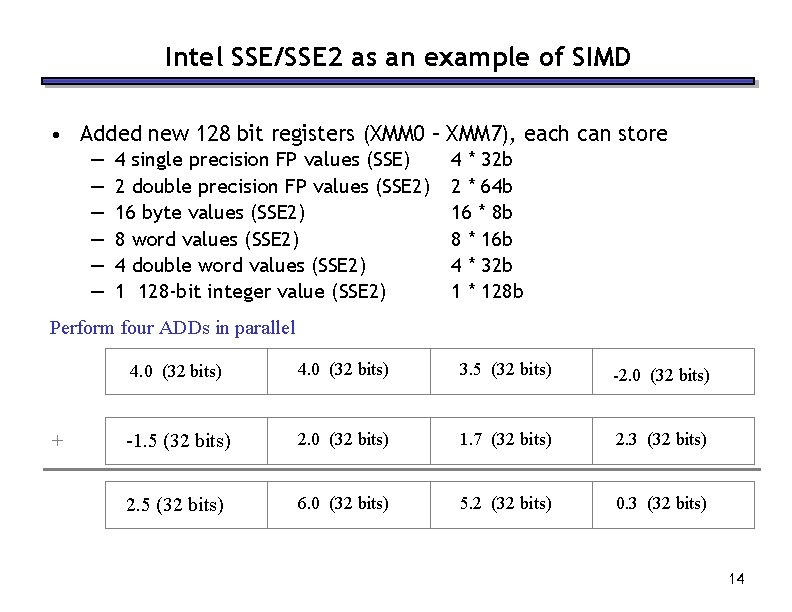

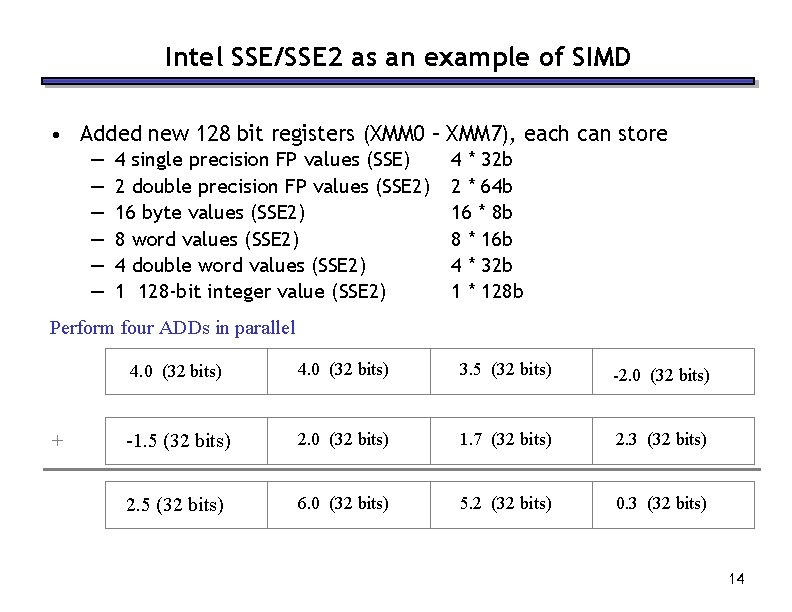

Intel SSE/SSE 2 as an example of SIMD • Added new 128 bit registers (XMM 0 – XMM 7), each can store — — — 4 single precision FP values (SSE) 2 double precision FP values (SSE 2) 16 byte values (SSE 2) 8 word values (SSE 2) 4 double word values (SSE 2) 1 128 -bit integer value (SSE 2) 4 * 32 b 2 * 64 b 16 * 8 b 8 * 16 b 4 * 32 b 1 * 128 b Perform four ADDs in parallel + 4. 0 (32 bits) 3. 5 (32 bits) -2. 0 (32 bits) -1. 5 (32 bits) 2. 0 (32 bits) 1. 7 (32 bits) 2. 3 (32 bits) 2. 5 (32 bits) 6. 0 (32 bits) 5. 2 (32 bits) 0. 3 (32 bits) 14

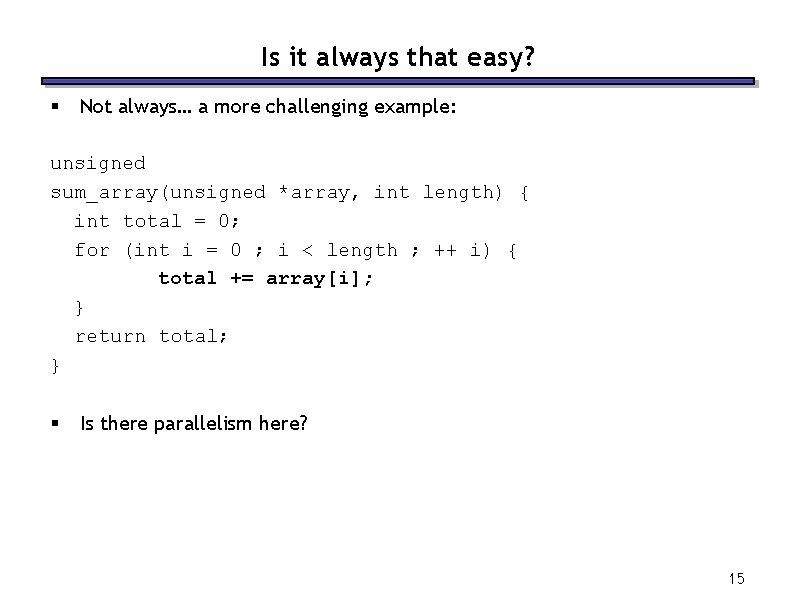

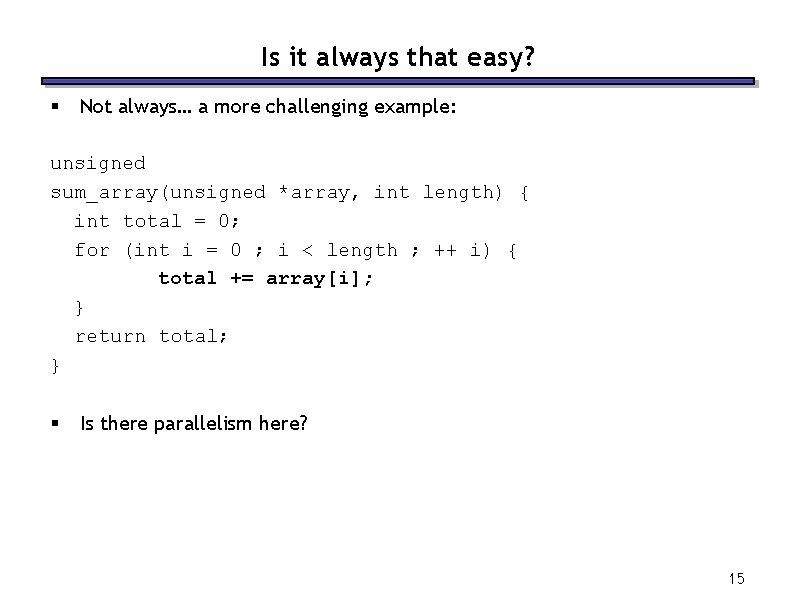

Is it always that easy? § Not always… a more challenging example: unsigned sum_array(unsigned *array, int length) { int total = 0; for (int i = 0 ; i < length ; ++ i) { total += array[i]; } return total; } § Is there parallelism here? 15

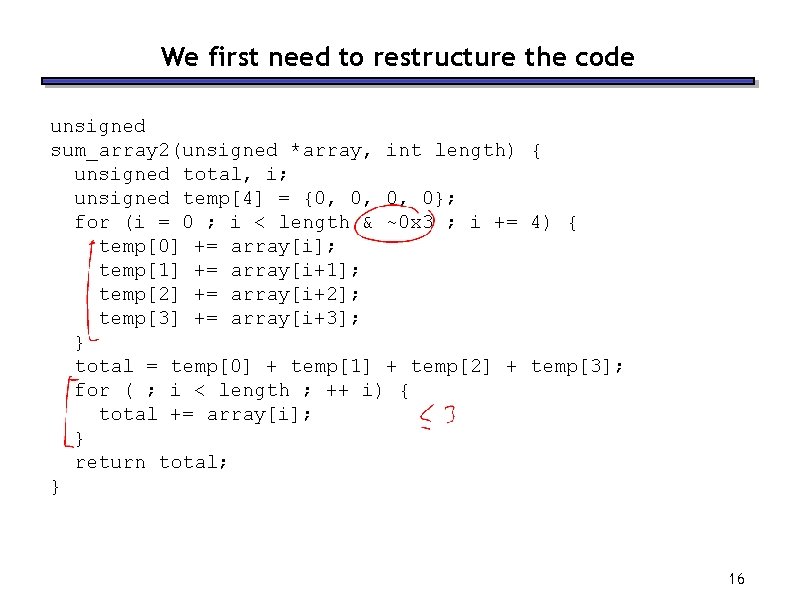

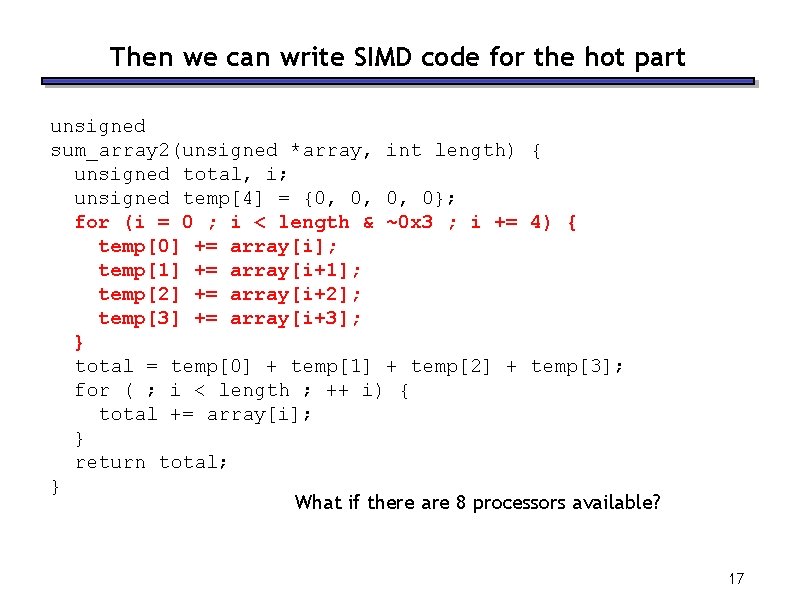

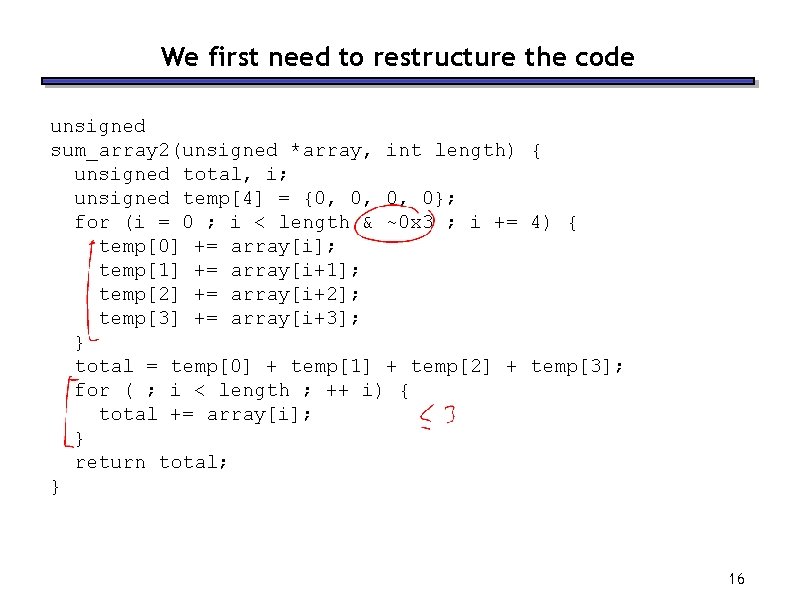

We first need to restructure the code unsigned sum_array 2(unsigned *array, int length) { unsigned total, i; unsigned temp[4] = {0, 0, 0, 0}; for (i = 0 ; i < length & ~0 x 3 ; i += 4) { temp[0] += array[i]; temp[1] += array[i+1]; temp[2] += array[i+2]; temp[3] += array[i+3]; } total = temp[0] + temp[1] + temp[2] + temp[3]; for ( ; i < length ; ++ i) { total += array[i]; } return total; } 16

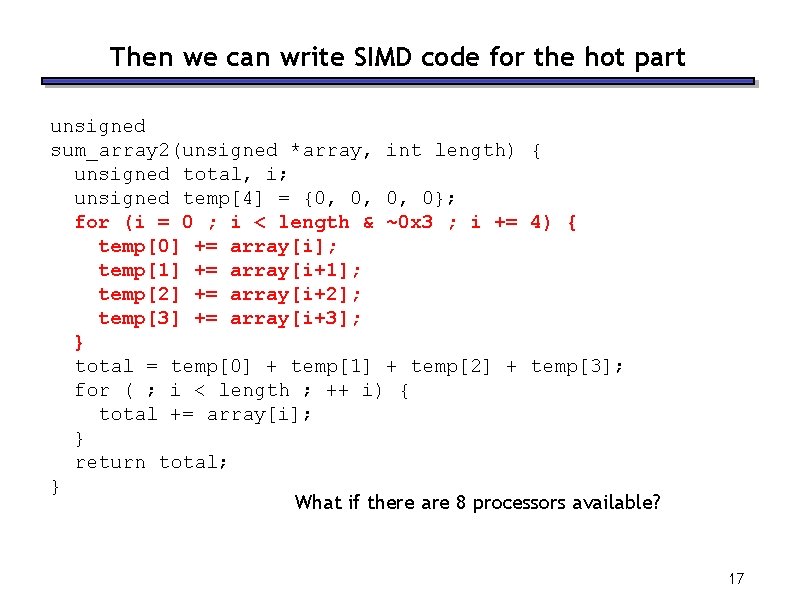

Then we can write SIMD code for the hot part unsigned sum_array 2(unsigned *array, int length) { unsigned total, i; unsigned temp[4] = {0, 0, 0, 0}; for (i = 0 ; i < length & ~0 x 3 ; i += 4) { temp[0] += array[i]; temp[1] += array[i+1]; temp[2] += array[i+2]; temp[3] += array[i+3]; } total = temp[0] + temp[1] + temp[2] + temp[3]; for ( ; i < length ; ++ i) { total += array[i]; } return total; } What if there are 8 processors available? 17

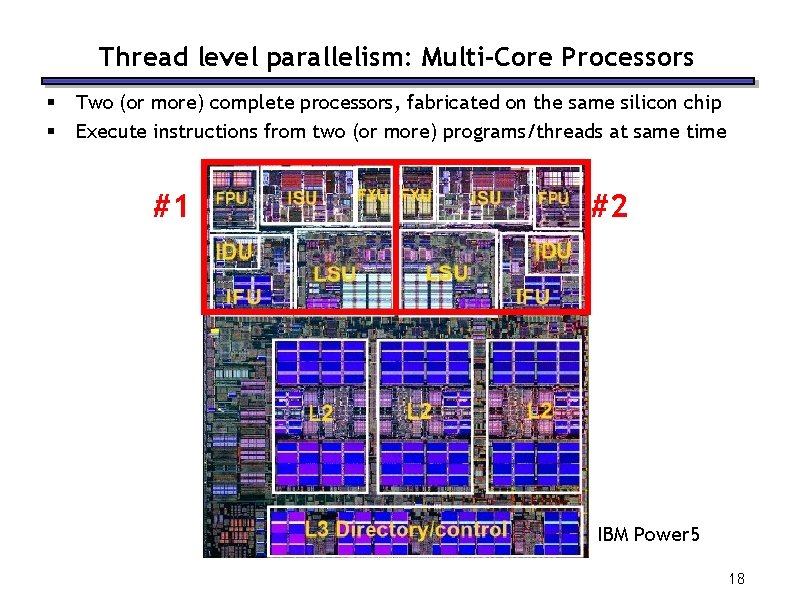

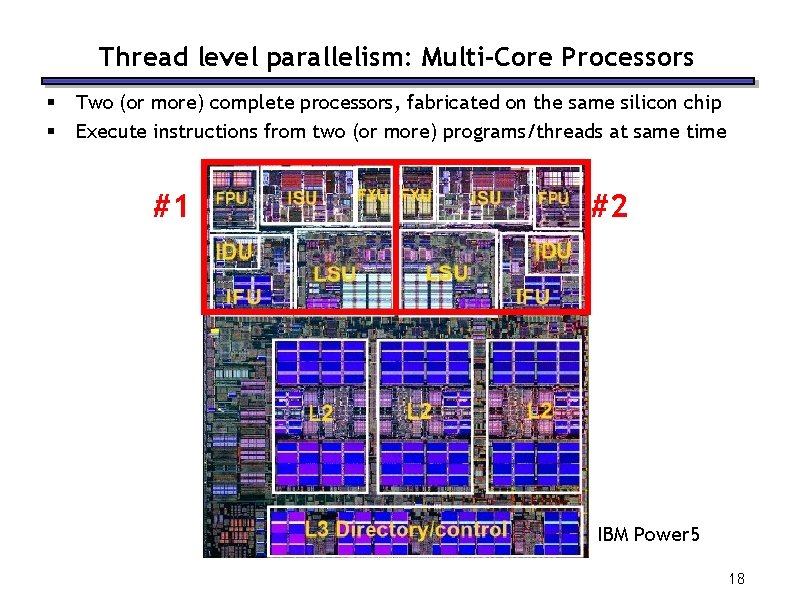

Thread level parallelism: Multi-Core Processors § § Two (or more) complete processors, fabricated on the same silicon chip Execute instructions from two (or more) programs/threads at same time #1 #2 IBM Power 5 18

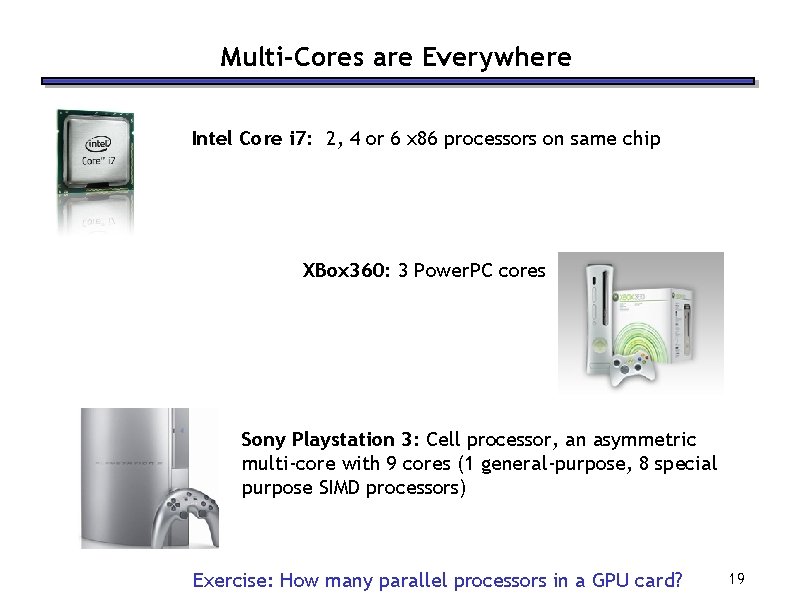

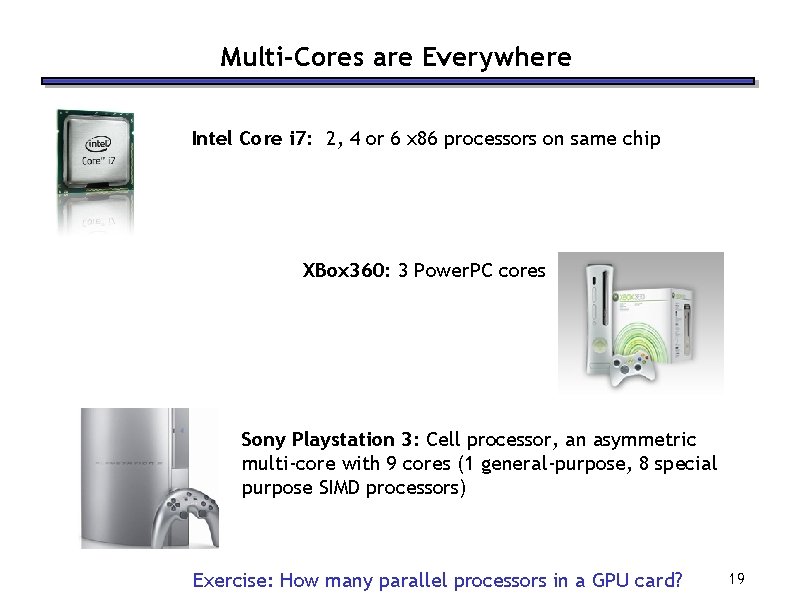

Multi-Cores are Everywhere Intel Core i 7: 2, 4 or 6 x 86 processors on same chip XBox 360: 3 Power. PC cores Sony Playstation 3: Cell processor, an asymmetric multi-core with 9 cores (1 general-purpose, 8 special purpose SIMD processors) Exercise: How many parallel processors in a GPU card? 19

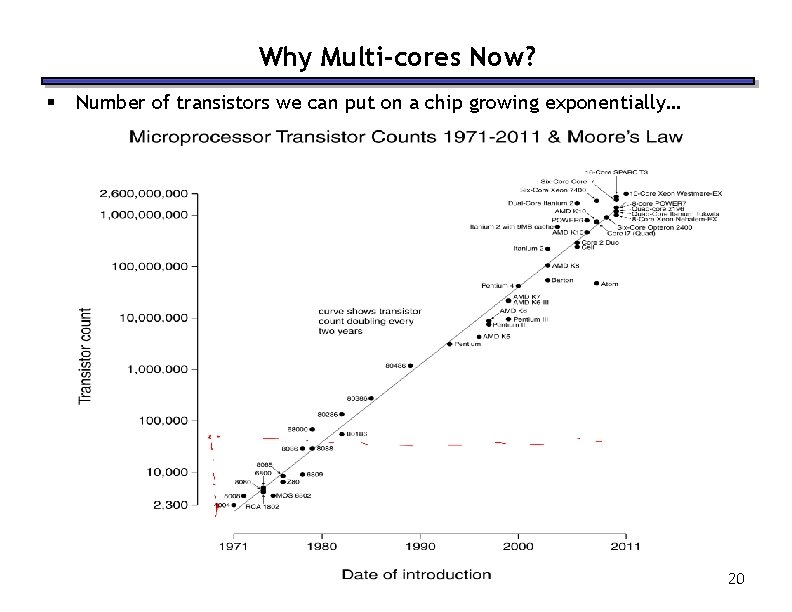

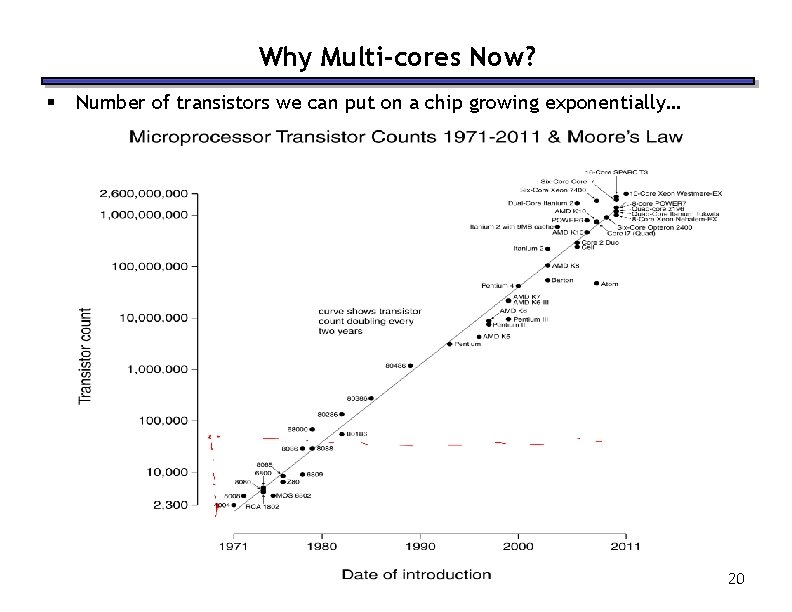

Why Multi-cores Now? § Number of transistors we can put on a chip growing exponentially… 20

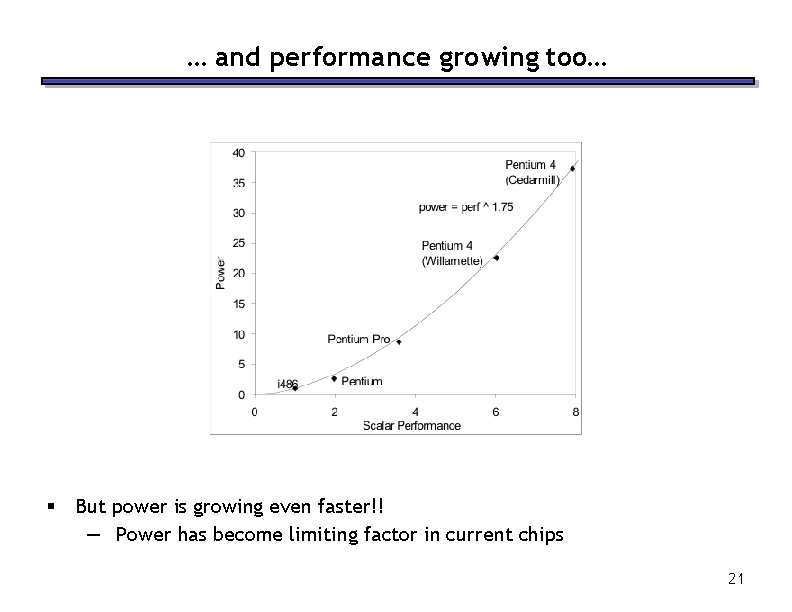

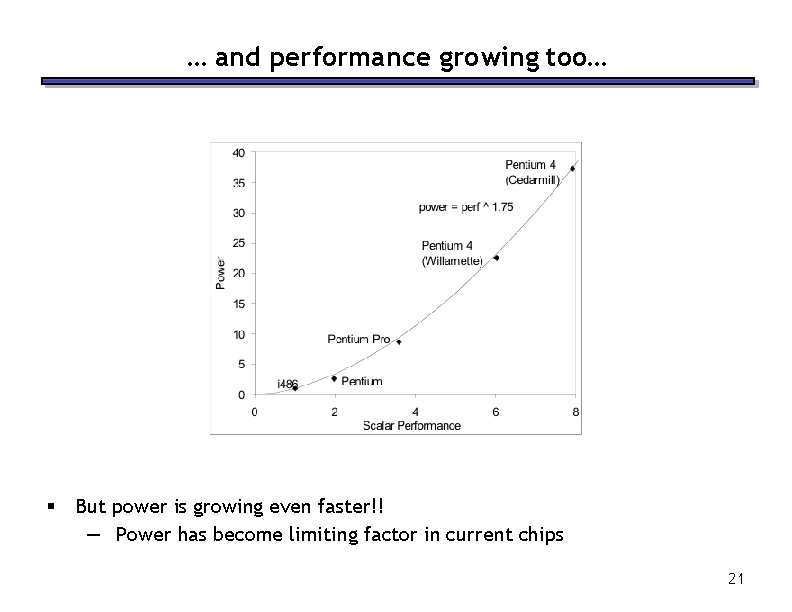

… and performance growing too… § But power is growing even faster!! — Power has become limiting factor in current chips 21

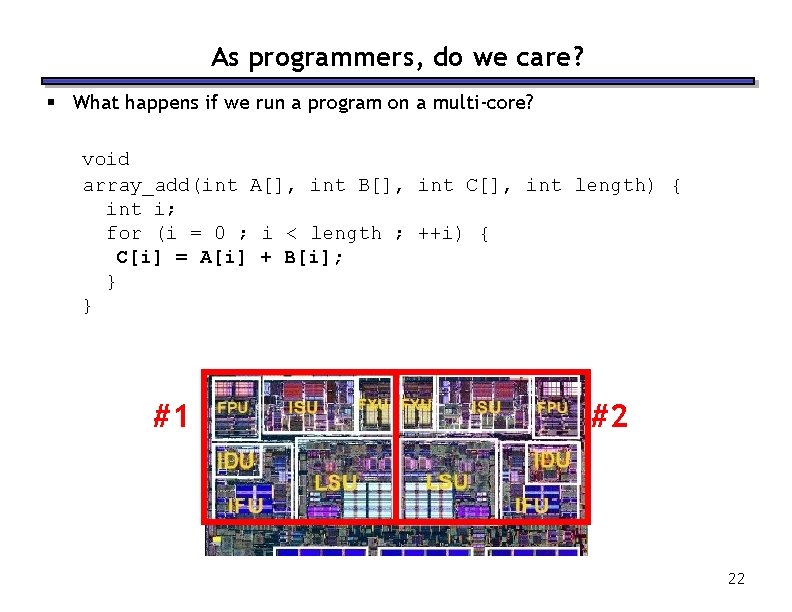

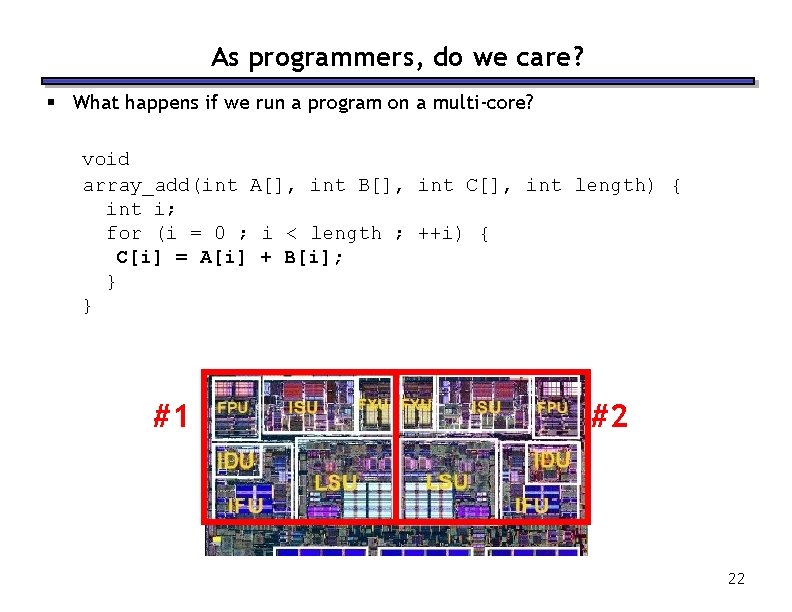

As programmers, do we care? § What happens if we run a program on a multi-core? void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { int i; for (i = 0 ; i < length ; ++i) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } } #1 #2 22

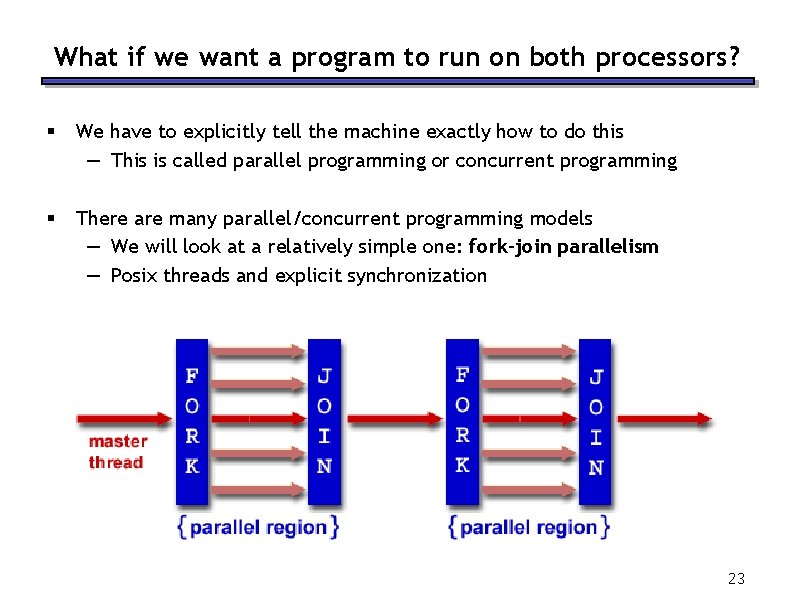

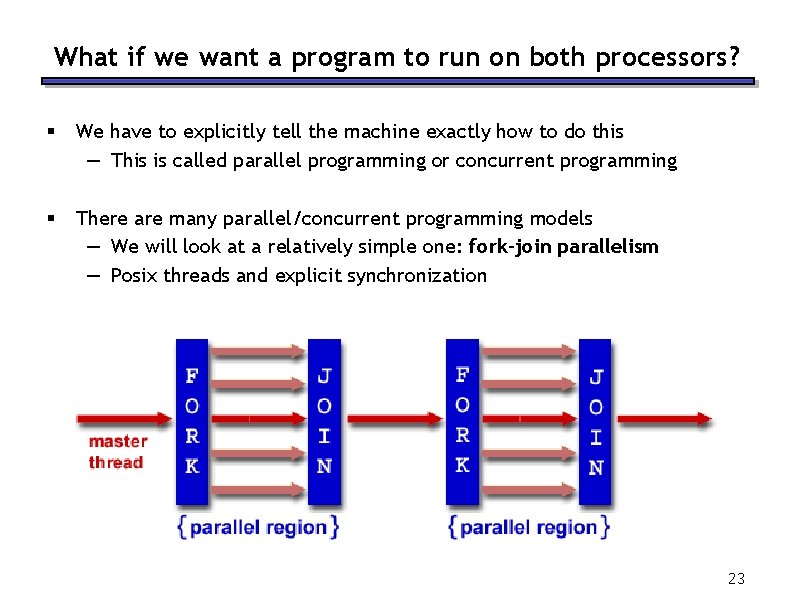

What if we want a program to run on both processors? § We have to explicitly tell the machine exactly how to do this — This is called parallel programming or concurrent programming § There are many parallel/concurrent programming models — We will look at a relatively simple one: fork-join parallelism — Posix threads and explicit synchronization 23

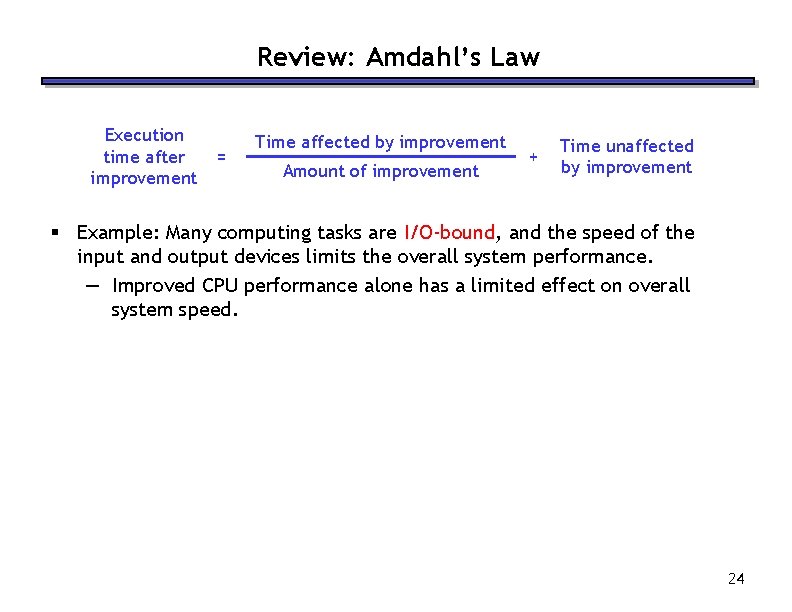

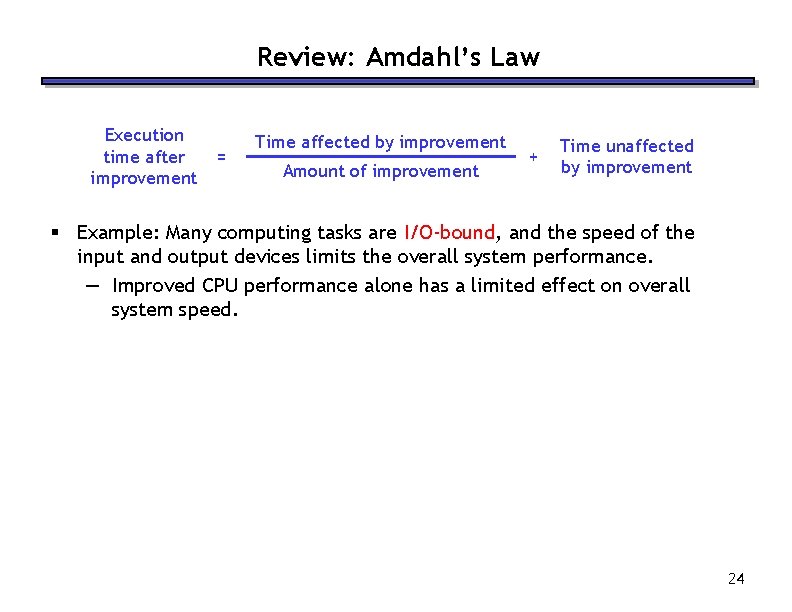

Review: Amdahl’s Law Execution time after improvement = Time affected by improvement Amount of improvement + Time unaffected by improvement § Example: Many computing tasks are I/O-bound, and the speed of the input and output devices limits the overall system performance. — Improved CPU performance alone has a limited effect on overall system speed. 24

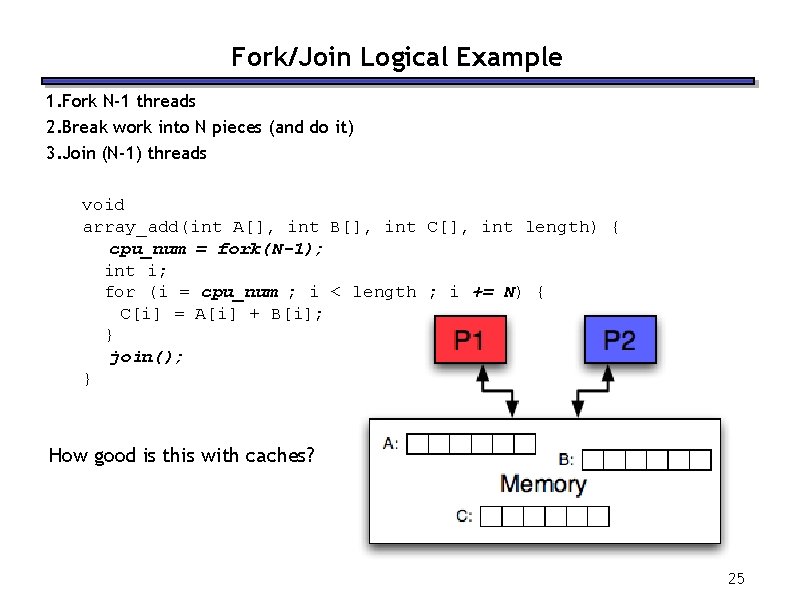

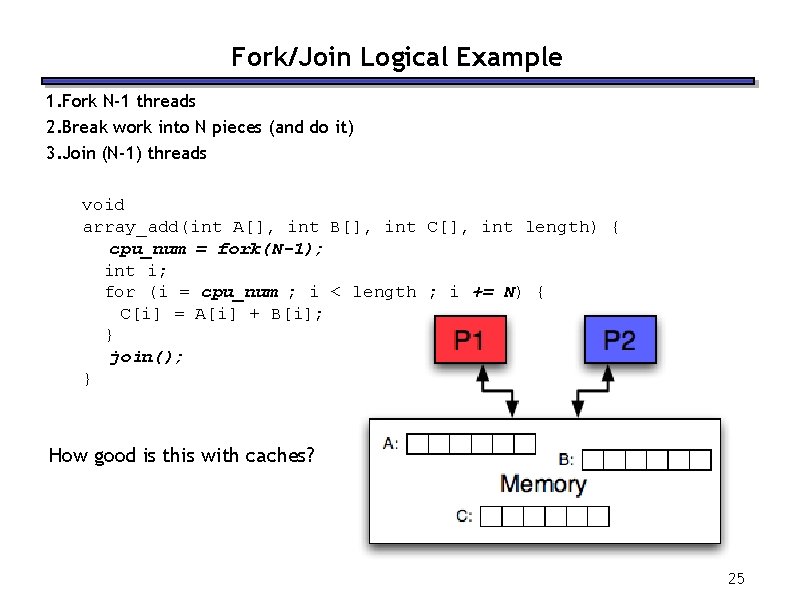

Fork/Join Logical Example 1. Fork N-1 threads 2. Break work into N pieces (and do it) 3. Join (N-1) threads void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { cpu_num = fork(N-1); int i; for (i = cpu_num ; i < length ; i += N) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } join(); } How good is this with caches? 25

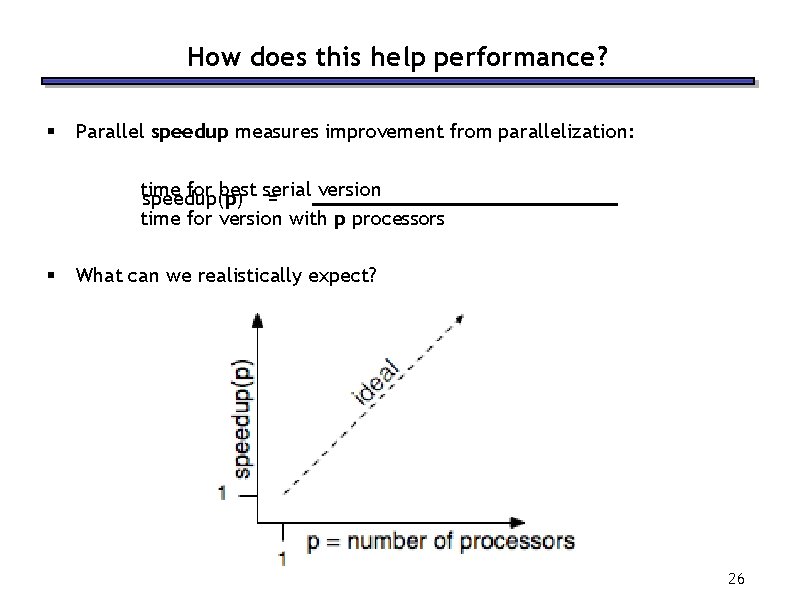

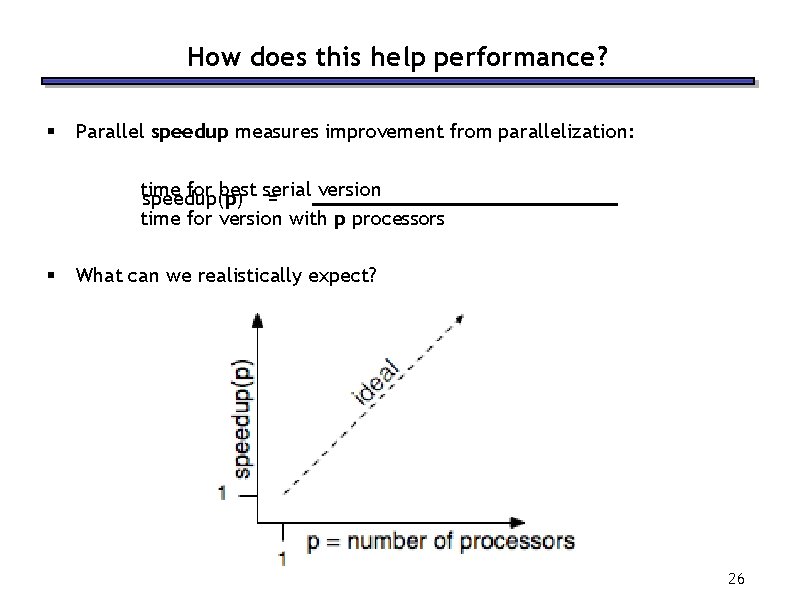

How does this help performance? § Parallel speedup measures improvement from parallelization: time for best serial version speedup(p) = time for version with p processors § What can we realistically expect? 26

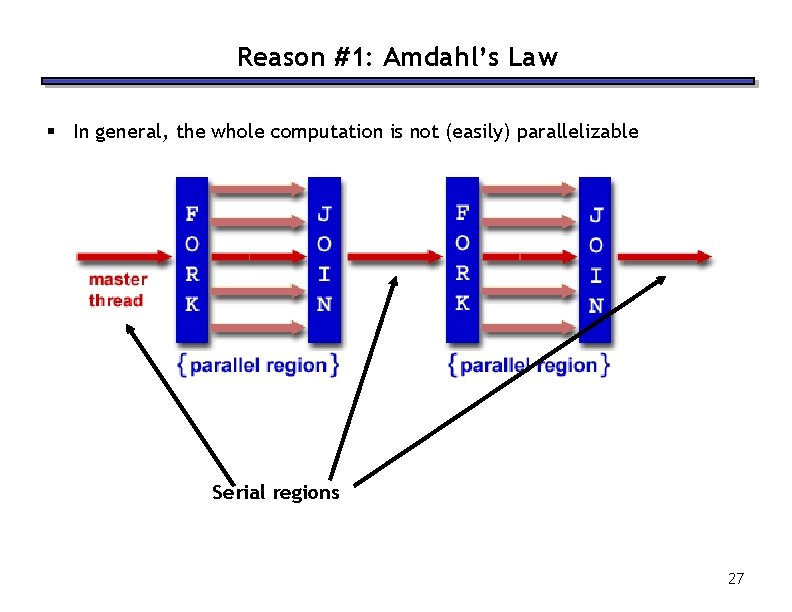

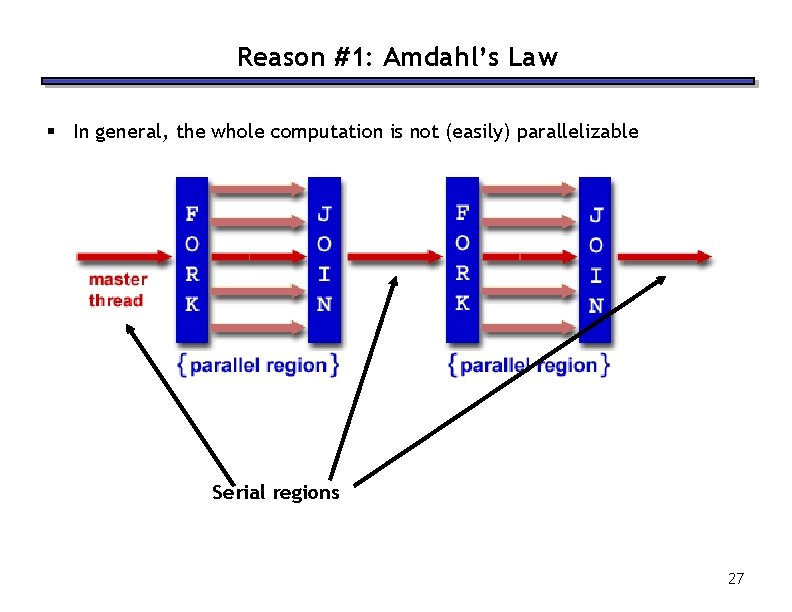

Reason #1: Amdahl’s Law § In general, the whole computation is not (easily) parallelizable Serial regions 27

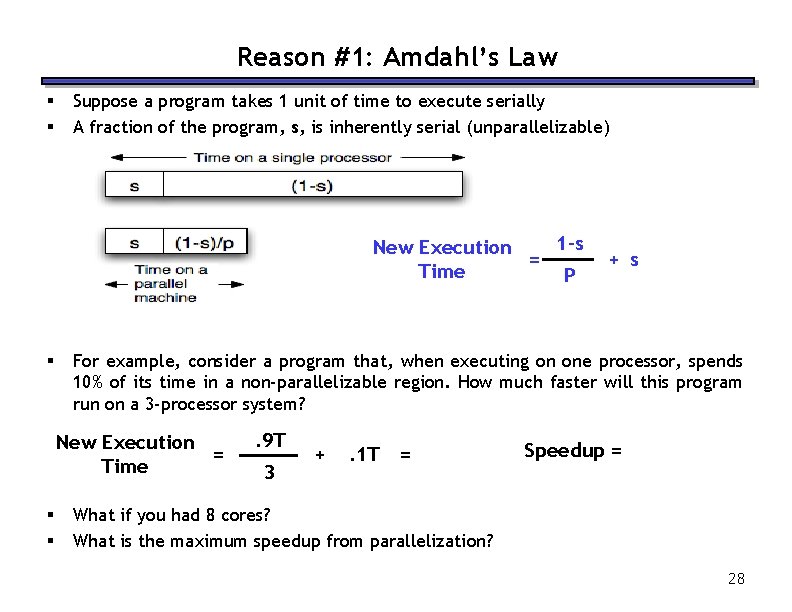

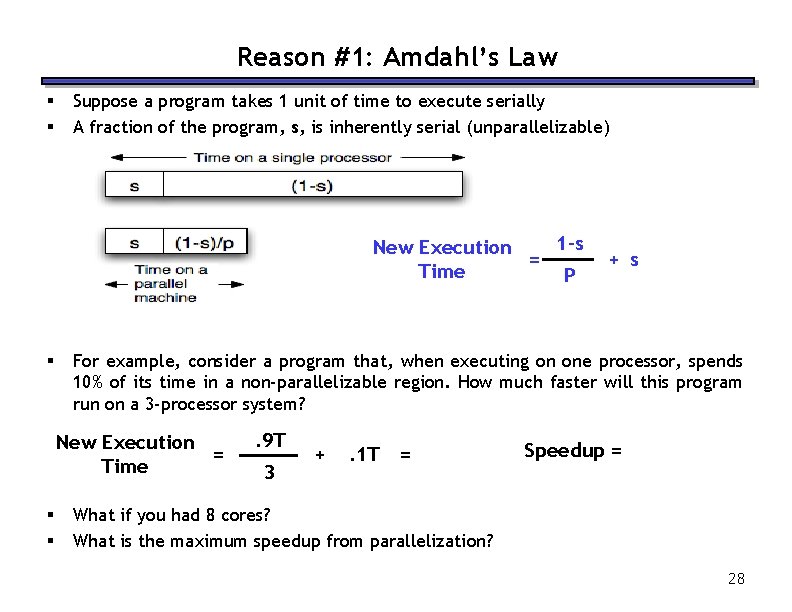

Reason #1: Amdahl’s Law § § Suppose a program takes 1 unit of time to execute serially A fraction of the program, s, is inherently serial (unparallelizable) 1 -s New Execution = Time P § For example, consider a program that, when executing on one processor, spends 10% of its time in a non-parallelizable region. How much faster will this program run on a 3 -processor system? New Execution = Time § § + s . 9 T 3 + . 1 T = Speedup = What if you had 8 cores? What is the maximum speedup from parallelization? 28

![Reason 2 Overhead void arrayaddint A int B int C int length cpunum Reason #2: Overhead void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { cpu_num](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/4c2e46c0001a571f8dd5864fbb9de5eb/image-29.jpg)

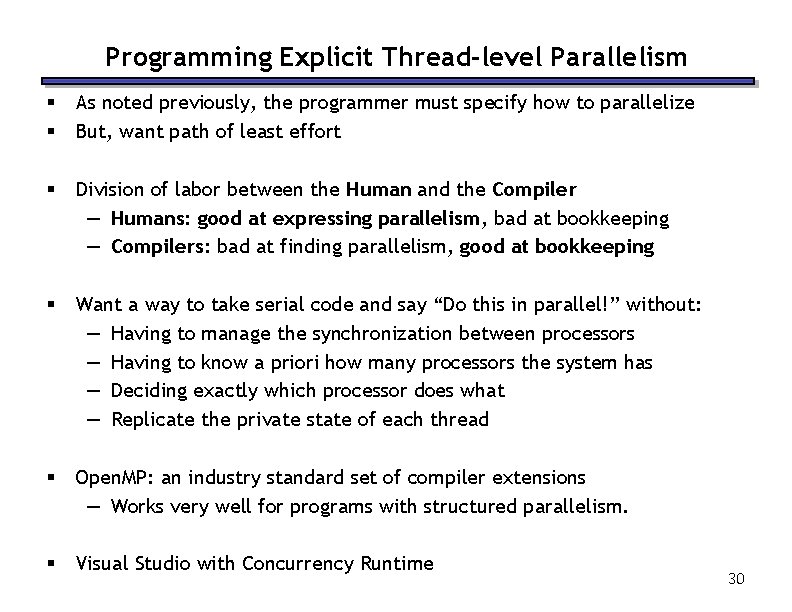

Reason #2: Overhead void array_add(int A[], int B[], int C[], int length) { cpu_num = fork(N-1); int i; for (i = cpu_num ; i < length ; i += N) { C[i] = A[i] + B[i]; } join(); } — Forking and joining is not instantaneous • Involves communicating between processors • May involve calls into the operating system — Depends on the implementation 1 -s New Execution = Time P + s + overhead(P) 29

Programming Explicit Thread-level Parallelism § § As noted previously, the programmer must specify how to parallelize But, want path of least effort § Division of labor between the Human and the Compiler — Humans: good at expressing parallelism, bad at bookkeeping — Compilers: bad at finding parallelism, good at bookkeeping § Want a way to take serial code and say “Do this in parallel!” without: — Having to manage the synchronization between processors — Having to know a priori how many processors the system has — Deciding exactly which processor does what — Replicate the private state of each thread § Open. MP: an industry standard set of compiler extensions — Works very well for programs with structured parallelism. § Visual Studio with Concurrency Runtime 30

New Programming Model § § § Scalable Task Oriented Statelessness 31

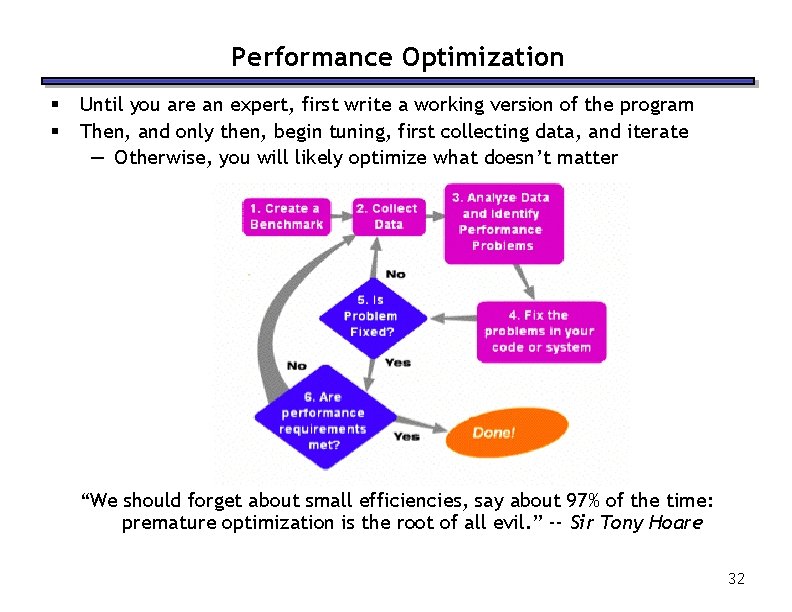

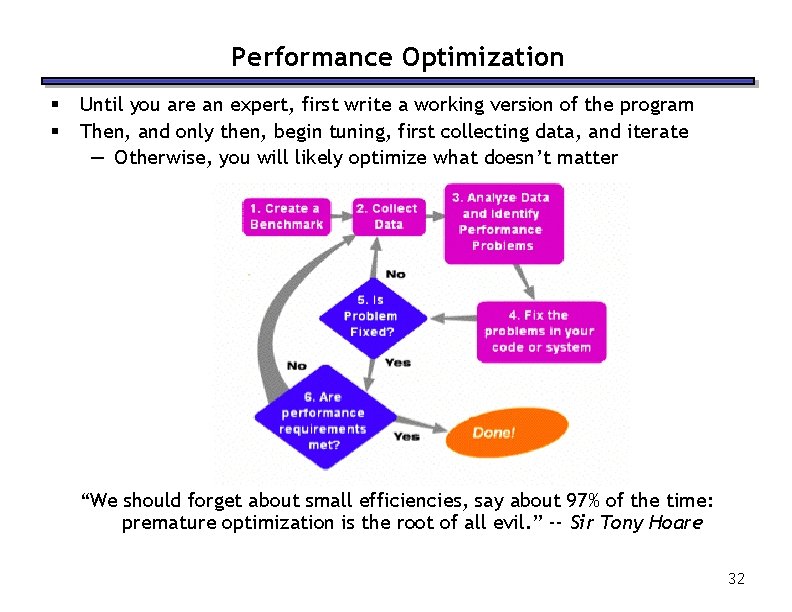

Performance Optimization § § Until you are an expert, first write a working version of the program Then, and only then, begin tuning, first collecting data, and iterate — Otherwise, you will likely optimize what doesn’t matter “We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. ” -- Sir Tony Hoare 32

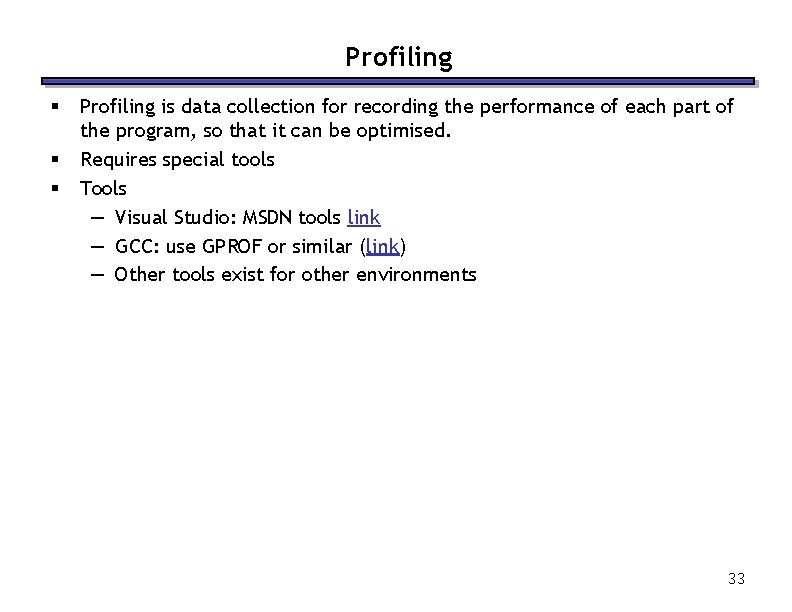

Profiling § § § Profiling is data collection for recording the performance of each part of the program, so that it can be optimised. Requires special tools Tools — Visual Studio: MSDN tools link — GCC: use GPROF or similar (link) — Other tools exist for other environments 33

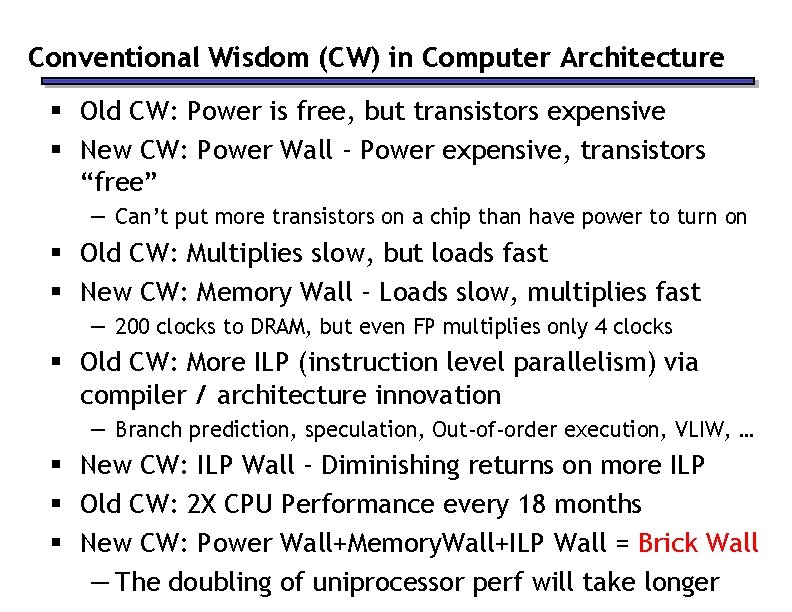

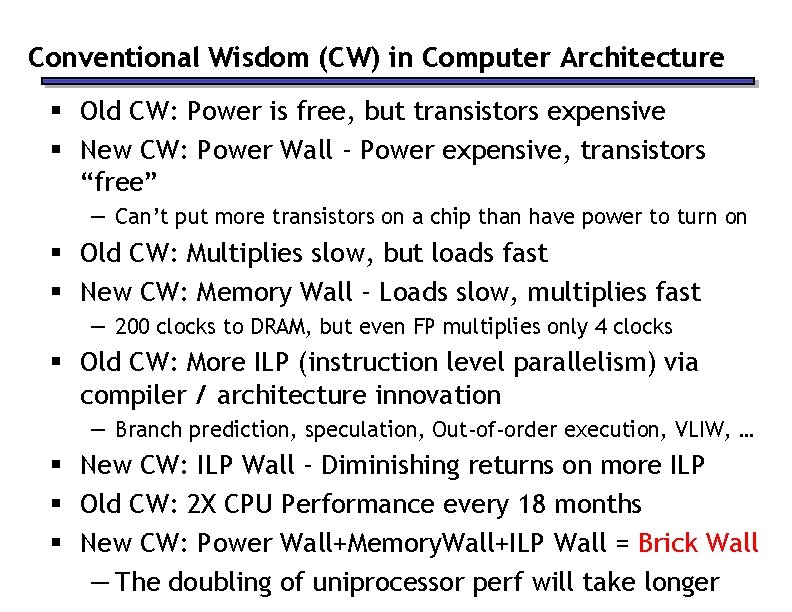

Fix only the big problems Pareto analysis to identify most significant problem Remember Amdahl’s law Pareto diagram from Wikipedia 34

Conventional Wisdom (CW) in Computer Architecture § Old CW: Power is free, but transistors expensive § New CW: Power Wall - Power expensive, transistors “free” — Can’t put more transistors on a chip than have power to turn on § Old CW: Multiplies slow, but loads fast § New CW: Memory Wall - Loads slow, multiplies fast — 200 clocks to DRAM, but even FP multiplies only 4 clocks § Old CW: More ILP (instruction level parallelism) via compiler / architecture innovation — Branch prediction, speculation, Out-of-order execution, VLIW, … § New CW: ILP Wall - Diminishing returns on more ILP § Old CW: 2 X CPU Performance every 18 months § New CW: Power Wall+Memory. Wall+ILP Wall = Brick Wall — The doubling of uniprocessor perf will take longer

Conventional Wisdom “The promise of parallelism has fascinated researchers for at least three decades. In the past, parallel computing efforts have shown promise and gathered investment, but in the end uniprocessor computing always prevailed. Nevertheless, we argue general-purpose computing is taking an irreversible step toward parallel architectures. ” – Berkeley View, December 2006

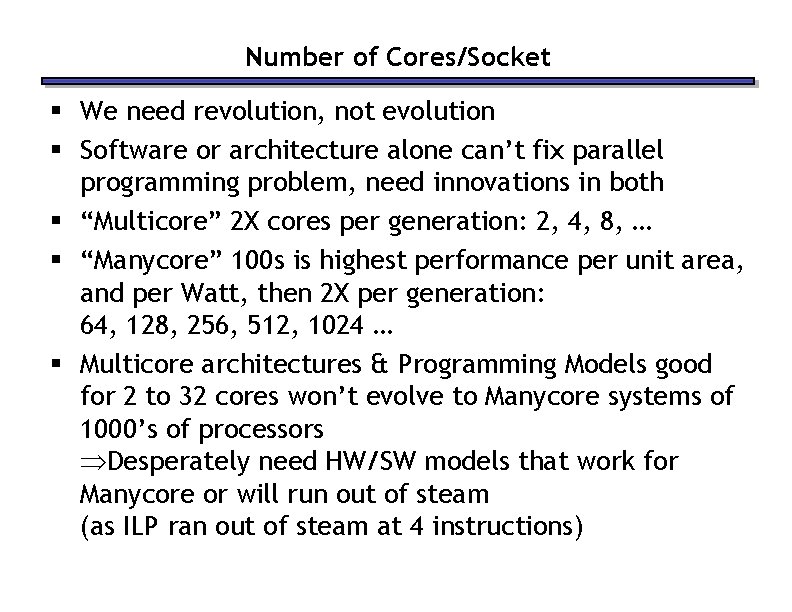

Parallelism again? What’s different this time? “This shift toward increasing parallelism is not a triumphant stride forward based on breakthroughs in novel software and architectures for parallelism; instead, this plunge into parallelism is actually a retreat from even greater challenges that thwart efficient silicon implementation of traditional uniprocessor architectures. ” – Berkeley View, December 2006 § HW/SW Industry bet its future that breakthroughs will appear before it’s too late view. eecs. berkeley. edu

Number of Cores/Socket § We need revolution, not evolution § Software or architecture alone can’t fix parallel programming problem, need innovations in both § “Multicore” 2 X cores per generation: 2, 4, 8, … § “Manycore” 100 s is highest performance per unit area, and per Watt, then 2 X per generation: 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024 … § Multicore architectures & Programming Models good for 2 to 32 cores won’t evolve to Manycore systems of 1000’s of processors Desperately need HW/SW models that work for Manycore or will run out of steam (as ILP ran out of steam at 4 instructions)

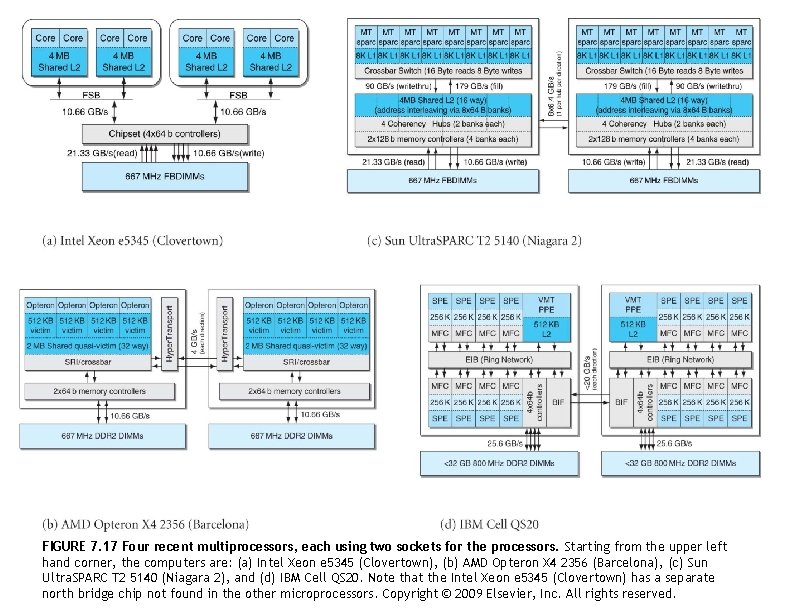

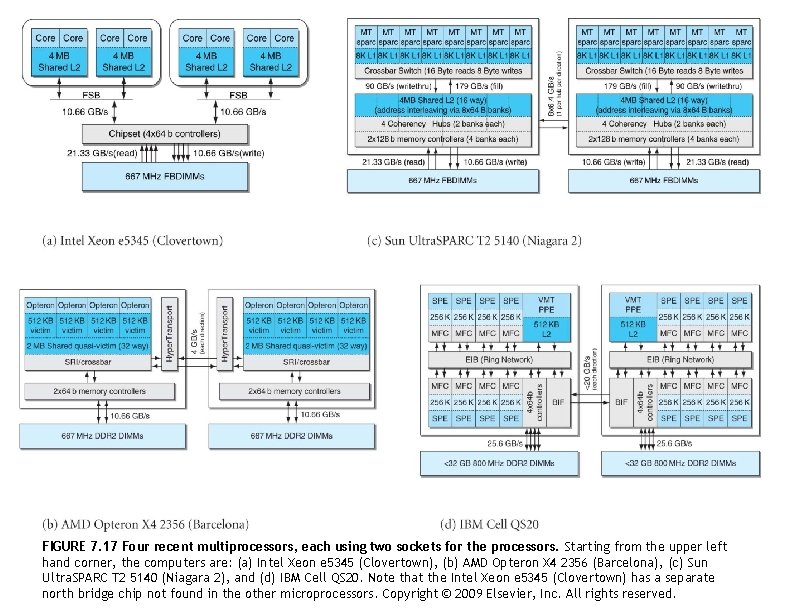

FIGURE 7. 17 Four recent multiprocessors, each using two sockets for the processors. Starting from the upper left hand corner, the computers are: (a) Intel Xeon e 5345 (Clovertown), (b) AMD Opteron X 4 2356 (Barcelona), (c) Sun Ultra. SPARC T 2 5140 (Niagara 2), and (d) IBM Cell QS 20. Note that the Intel Xeon e 5345 (Clovertown) has a separate north bridge chip not found in the other microprocessors. Copyright © 2009 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

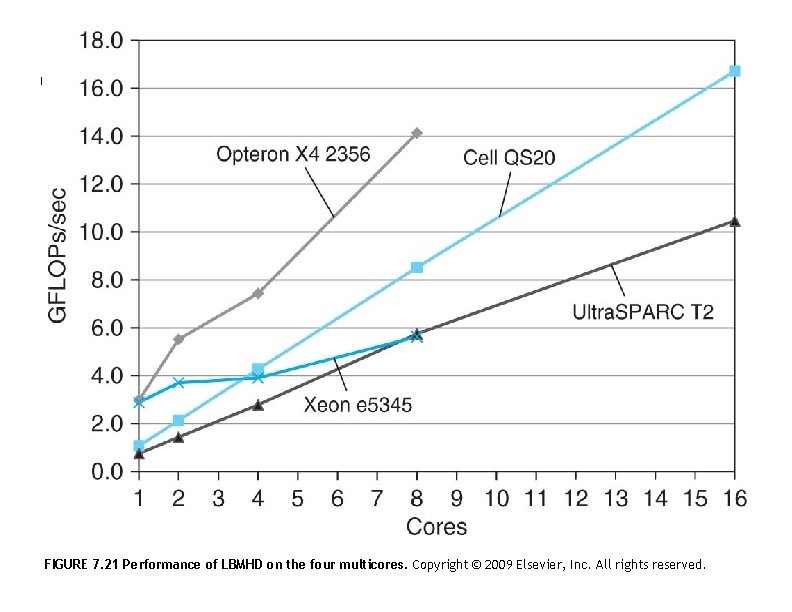

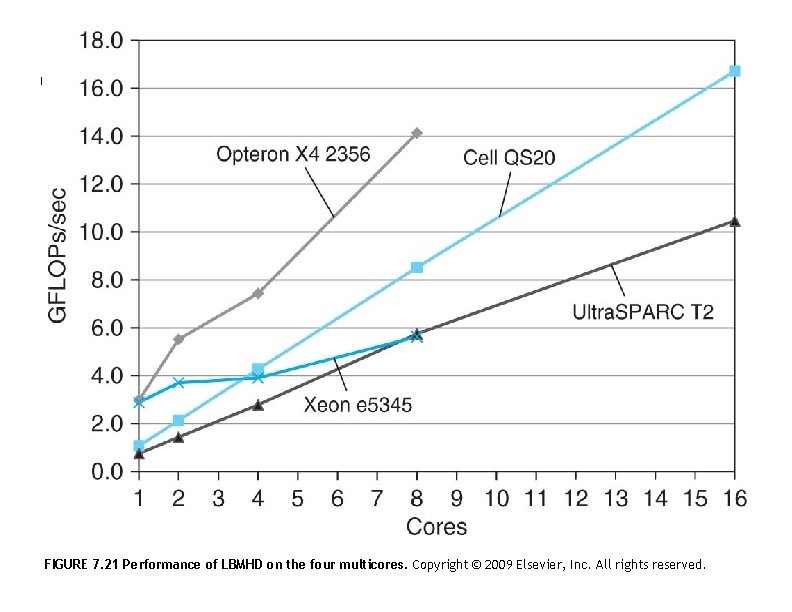

FIGURE 7. 21 Performance of LBMHD on the four multicores. Copyright © 2009 Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved.

41

Summary § Multi-core is having more than one processor on the same chip. — Most PCs/servers and game consoles are already multi-core — Results from Moore’s law and power constraint § Exploiting multi-core requires parallel programming — Automatically extracting parallelism too hard for compiler, in general. — But, can have compiler do much of the bookkeeping for us — Open. MP § Fork-Join model of parallelism — At parallel region, fork a bunch of threads, do the work in parallel, and then join, continuing with just one thread — Expect a speedup of less than P on P processors • Amdahl’s Law: speedup limited by serial portion of program • Overhead: forking and joining are not free § Everything is changing § Old conventional wisdom is out § We desperately need new approach to HW and SW based on parallelism since industry has bet its future that parallelism work 42