IRAM and ISTORE Projects Aaron Brown James Beck

IRAM and ISTORE Projects Aaron Brown, James Beck, Rich Fromm, Joe Gebis, Paul Harvey, Adam Janin, Dave Judd, Kimberly Keeton, Christoforos Kozyrakis, David Martin, Rich Martin, Thinh Nguyen, David Oppenheimer, Steve Pope, Randi Thomas, Noah Treuhaft, Sam Williams, John Kubiatowicz, Kathy Yelick, and David Patterson http: //iram. cs. berkeley. edu/[istore] Fall 2000 DIS DARPA Meeting Slide 1

IRAM and ISTORE Vision • Integrated processor in memory provides efficient access to high memory bandwidth • Two “Post-PC” applications: – IRAM: Single chip system for embedded and portable applications » Target media processing (speech, images, video, audio) – ISTORE: Building block when combined with disk for storage and retrieval servers » Up to 10 K nodes in one rack » Non-IRAM prototype addresses key scaling issues: availability, manageability, evolution Photo from Itsy, Inc. Slide 2

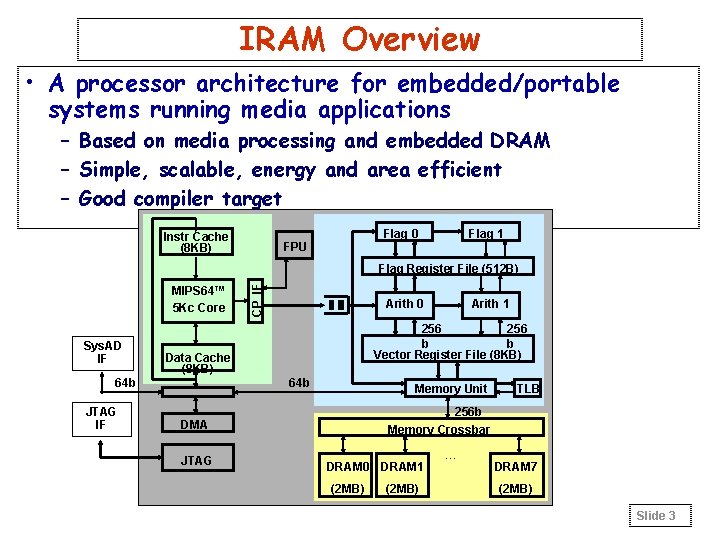

IRAM Overview • A processor architecture for embedded/portable systems running media applications – Based on media processing and embedded DRAM – Simple, scalable, energy and area efficient – Good compiler target Instr Cache (8 KB) Flag 0 FPU Flag 1 MIPS 64™ 5 Kc Core Sys. AD IF Arith 0 64 b Memory Unit TLB 256 b Memory Crossbar DMA JTAG Arith 1 256 b b Vector Register File (8 KB) Data Cache (8 KB) 64 b JTAG IF CP IF Flag Register File (512 B) DRAM 0 DRAM 1 (2 MB) … DRAM 7 (2 MB) Slide 3

Architecture Details • MIPS 64™ 5 Kc core (200 MHz) – Single-issue scalar core with 8 Kbyte I&D caches • Vector unit (200 MHz) – 8 KByte register file (32 64 b elements per register) – 256 b datapaths, can be subdivided into 16 b, 32 b, 64 b: » 2 arithmetic (1 FP, single), 2 flag processing – Memory unit » 4 address generators for strided/indexed accesses • Main memory system – 8 2 -MByte DRAM macros » 25 ns random access time, 7. 5 ns page access time – Crossbar interconnect » 12. 8 GBytes/s peak bandwidth per direction (load/store) • Off-chip interface – 2 channel DMA engine and 64 n Sys. AD bus Slide 4

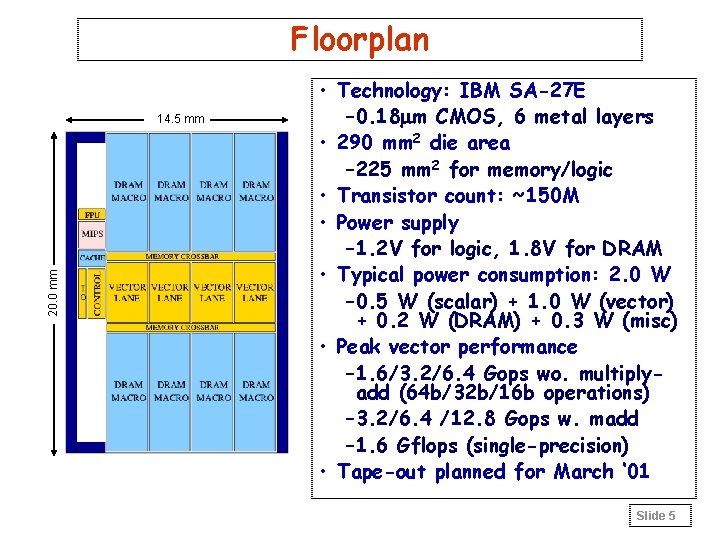

Floorplan 20. 0 mm 14. 5 mm • Technology: IBM SA-27 E – 0. 18 mm CMOS, 6 metal layers • 290 mm 2 die area – 225 mm 2 for memory/logic • Transistor count: ~150 M • Power supply – 1. 2 V for logic, 1. 8 V for DRAM • Typical power consumption: 2. 0 W – 0. 5 W (scalar) + 1. 0 W (vector) + 0. 2 W (DRAM) + 0. 3 W (misc) • Peak vector performance – 1. 6/3. 2/6. 4 Gops wo. multiplyadd (64 b/32 b/16 b operations) – 3. 2/6. 4 /12. 8 Gops w. madd – 1. 6 Gflops (single-precision) • Tape-out planned for March ‘ 01 Slide 5

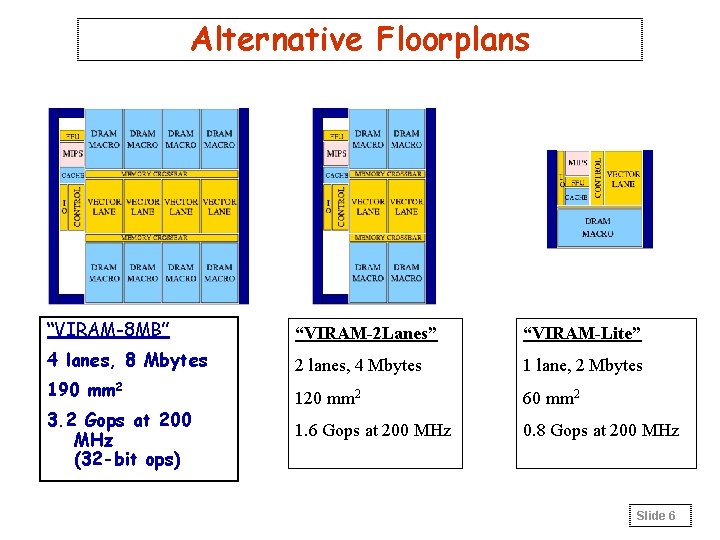

Alternative Floorplans “VIRAM-8 MB” “VIRAM-2 Lanes” “VIRAM-Lite” 4 lanes, 8 Mbytes 2 lanes, 4 Mbytes 1 lane, 2 Mbytes 190 mm 2 120 mm 2 60 mm 2 1. 6 Gops at 200 MHz 0. 8 Gops at 200 MHz 3. 2 Gops at 200 MHz (32 -bit ops) Slide 6

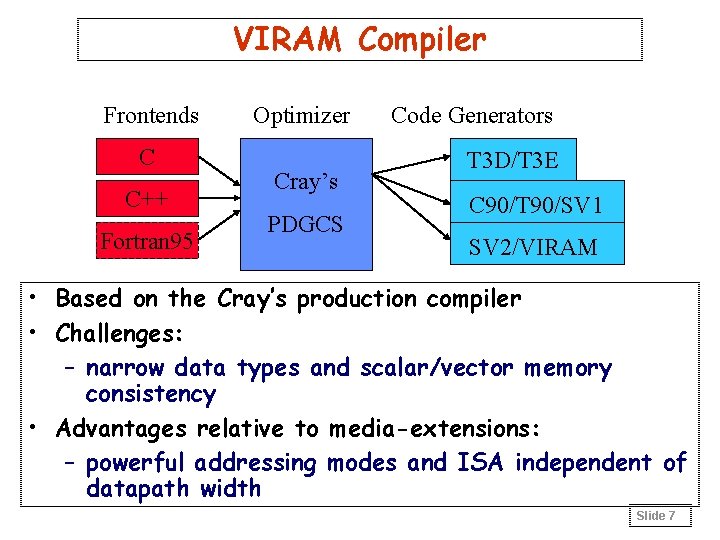

VIRAM Compiler Frontends C C++ Fortran 95 Optimizer Cray’s PDGCS Code Generators T 3 D/T 3 E C 90/T 90/SV 1 SV 2/VIRAM • Based on the Cray’s production compiler • Challenges: – narrow data types and scalar/vector memory consistency • Advantages relative to media-extensions: – powerful addressing modes and ISA independent of datapath width Slide 7

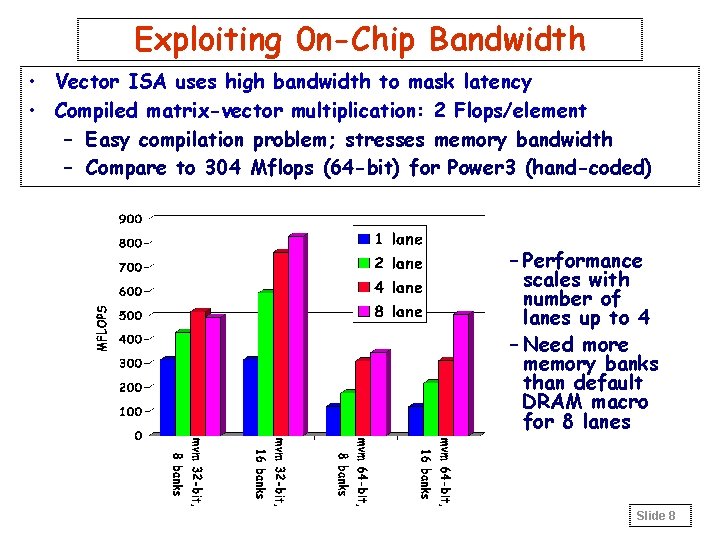

Exploiting 0 n-Chip Bandwidth • Vector ISA uses high bandwidth to mask latency • Compiled matrix-vector multiplication: 2 Flops/element – Easy compilation problem; stresses memory bandwidth – Compare to 304 Mflops (64 -bit) for Power 3 (hand-coded) – Performance scales with number of lanes up to 4 – Need more memory banks than default DRAM macro for 8 lanes Slide 8

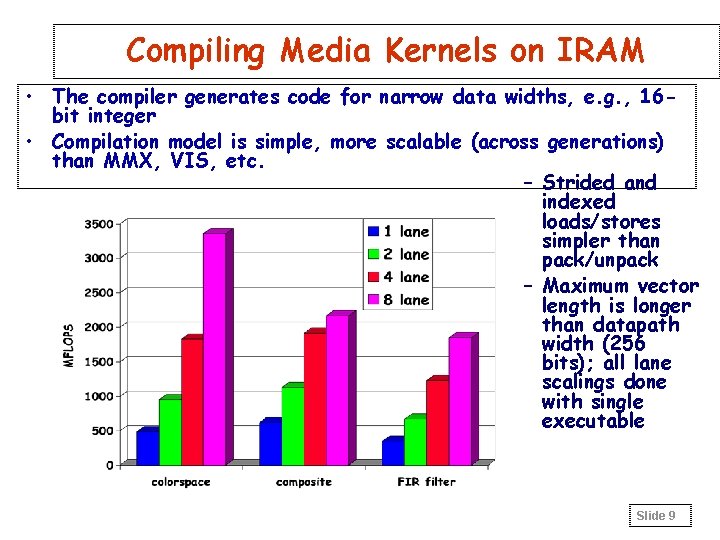

Compiling Media Kernels on IRAM • The compiler generates code for narrow data widths, e. g. , 16 bit integer • Compilation model is simple, more scalable (across generations) than MMX, VIS, etc. – Strided and indexed loads/stores simpler than pack/unpack – Maximum vector length is longer than datapath width (256 bits); all lane scalings done with single executable Slide 9

IRAM Status • Chip – ISA has not changed significantly in over a year – Verilog complete, except SRAM for scalar cache – Testing framework in place • Compiler – Backend code generation complete – Continued performance improvements, especially for narrow data widths • Application & Benchmarks – Handcoded kernels better than MMX, VIS, gp DSPs » DCT, FFT, MVM, convolution, image composition, … – Compiled kernels demonstrate ISA advantages » MVM, sparse MVM, decrypt, image composition, … – Full applications: H 263 encoding (done), speech (underway) Slide 10

Scaling to 10 K Processors • IRAM + micro-disk offer huge scaling opportunities • Still many hard system problems (AME) – Availability » systems should continue to meet quality of service goals despite hardware and software failures – Maintainability » systems should require only minimal ongoing human administration, regardless of scale or complexity – Evolutionary Growth » systems should evolve gracefully in terms of performance, maintainability, and availability as they are grown/upgraded/expanded • These are problems at today’s scales, and will only get worse as systems grow Slide 11

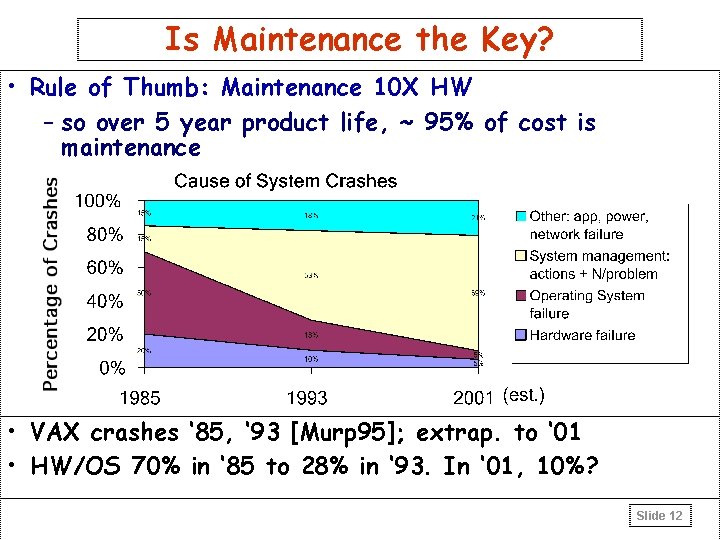

Is Maintenance the Key? • Rule of Thumb: Maintenance 10 X HW – so over 5 year product life, ~ 95% of cost is maintenance • VAX crashes ‘ 85, ‘ 93 [Murp 95]; extrap. to ‘ 01 • HW/OS 70% in ‘ 85 to 28% in ‘ 93. In ‘ 01, 10%? Slide 12

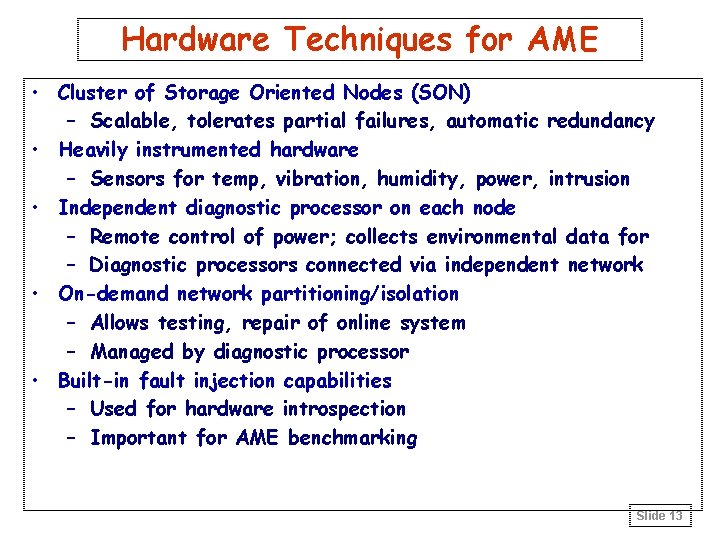

Hardware Techniques for AME • Cluster of Storage Oriented Nodes (SON) – Scalable, tolerates partial failures, automatic redundancy • Heavily instrumented hardware – Sensors for temp, vibration, humidity, power, intrusion • Independent diagnostic processor on each node – Remote control of power; collects environmental data for – Diagnostic processors connected via independent network • On-demand network partitioning/isolation – Allows testing, repair of online system – Managed by diagnostic processor • Built-in fault injection capabilities – Used for hardware introspection – Important for AME benchmarking Slide 13

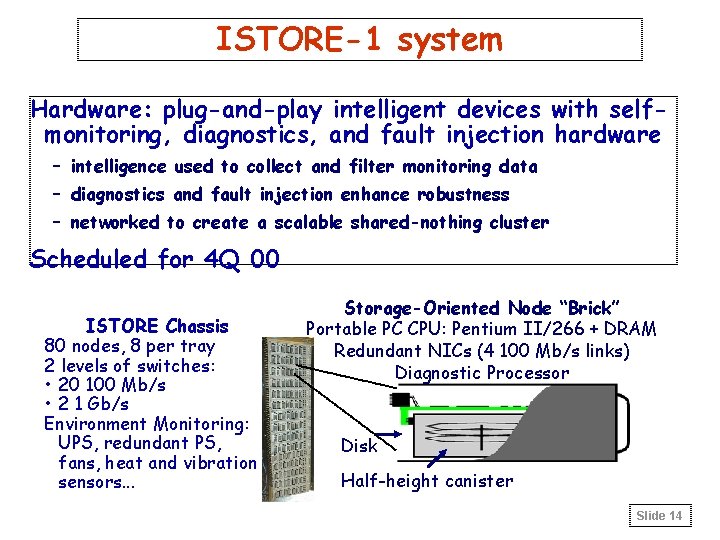

ISTORE-1 system Hardware: plug-and-play intelligent devices with selfmonitoring, diagnostics, and fault injection hardware – intelligence used to collect and filter monitoring data – diagnostics and fault injection enhance robustness – networked to create a scalable shared-nothing cluster Scheduled for 4 Q 00 ISTORE Chassis 80 nodes, 8 per tray 2 levels of switches: • 20 100 Mb/s • 2 1 Gb/s Environment Monitoring: UPS, redundant PS, fans, heat and vibration sensors. . . Storage-Oriented Node “Brick” Portable PC CPU: Pentium II/266 + DRAM Redundant NICs (4 100 Mb/s links) Diagnostic Processor Disk Half-height canister Slide 14

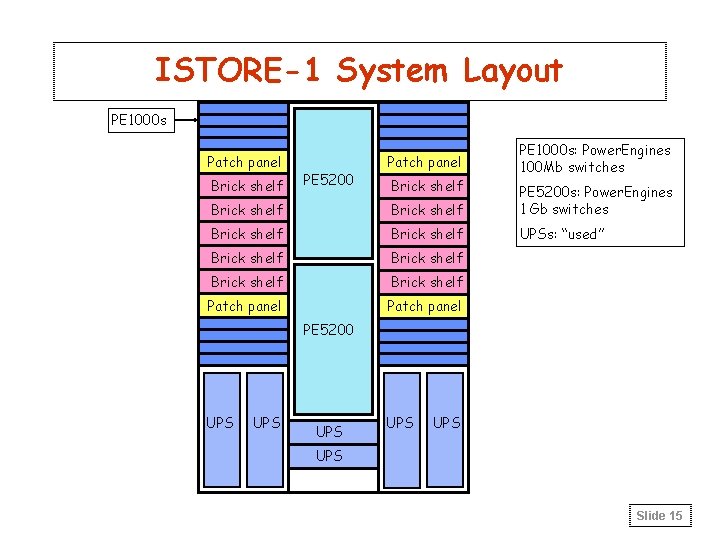

ISTORE-1 System Layout PE 1000 s Patch panel Brick shelf PE 5200 Patch panel Brick shelf PE 1000 s: Power. Engines 100 Mb switches Brick shelf PE 5200 s: Power. Engines 1 Gb switches Brick shelf UPSs: “used” Brick shelf Patch panel PE 5200 UPS UPS UPS Slide 15

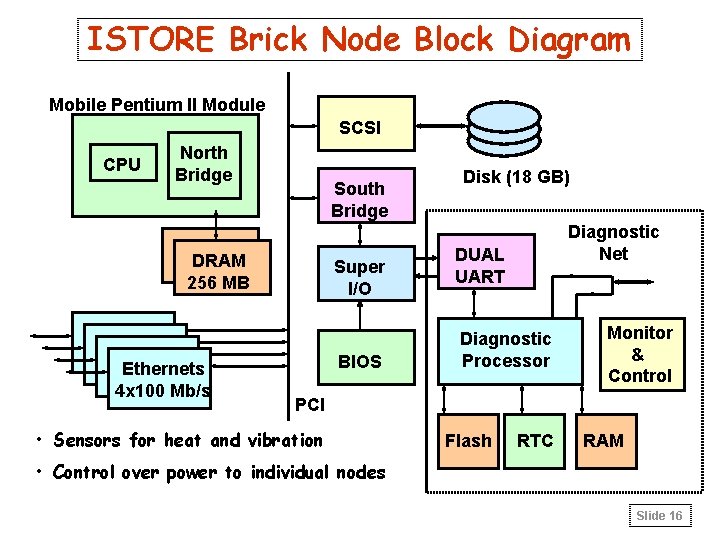

ISTORE Brick Node Block Diagram Mobile Pentium II Module SCSI CPU North Bridge South Bridge DRAM 256 MB Ethernets 4 x 100 Mb/s Super I/O BIOS Disk (18 GB) Diagnostic Net DUAL UART Diagnostic Processor Monitor & Control PCI • Sensors for heat and vibration Flash RTC RAM • Control over power to individual nodes Slide 16

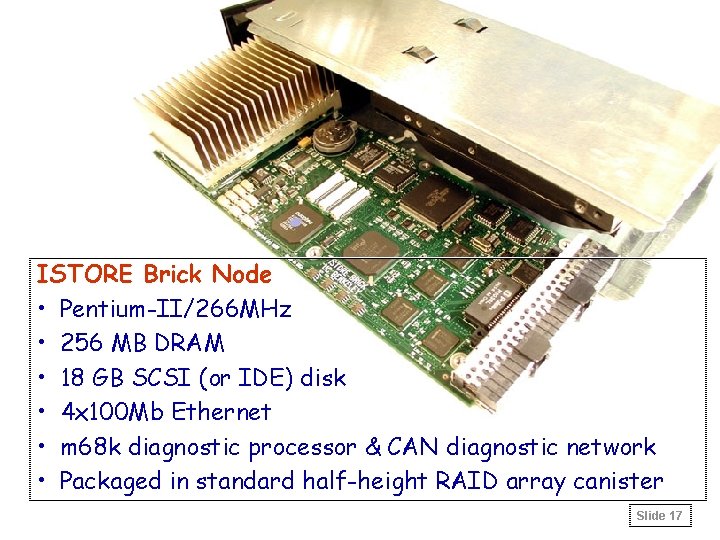

ISTORE Brick Node • Pentium-II/266 MHz • 256 MB DRAM • 18 GB SCSI (or IDE) disk • 4 x 100 Mb Ethernet • m 68 k diagnostic processor & CAN diagnostic network • Packaged in standard half-height RAID array canister Slide 17

Software Techniques • Reactive introspection – “Mining” available system data • Proactive introspection – Isolation + fault insertion => test recovery code • Semantic redundancy – Use of coding and application-specific checkpoints • Self-Scrubbing data structures – Check (and repair? ) complex distributed structures • Load adaptation for performance faults – Dynamic load balancing for “regular” computations • Benchmarking – Define quantitative evaluations for AME Slide 18

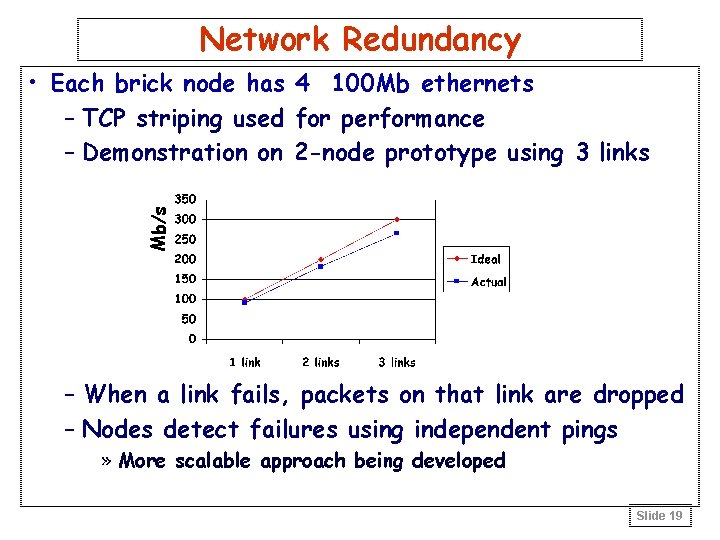

Network Redundancy Mb/s • Each brick node has 4 100 Mb ethernets – TCP striping used for performance – Demonstration on 2 -node prototype using 3 links – When a link fails, packets on that link are dropped – Nodes detect failures using independent pings » More scalable approach being developed Slide 19

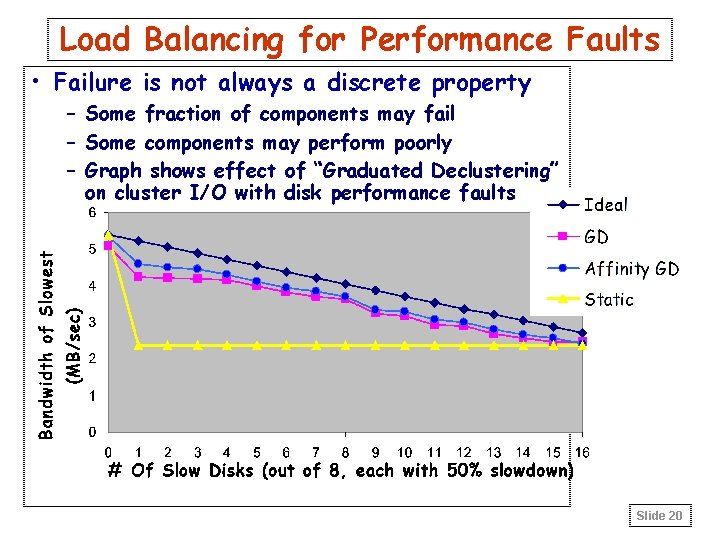

Load Balancing for Performance Faults • Failure is not always a discrete property – Some fraction of components may fail – Some components may perform poorly – Graph shows effect of “Graduated Declustering” on cluster I/O with disk performance faults Slide 20

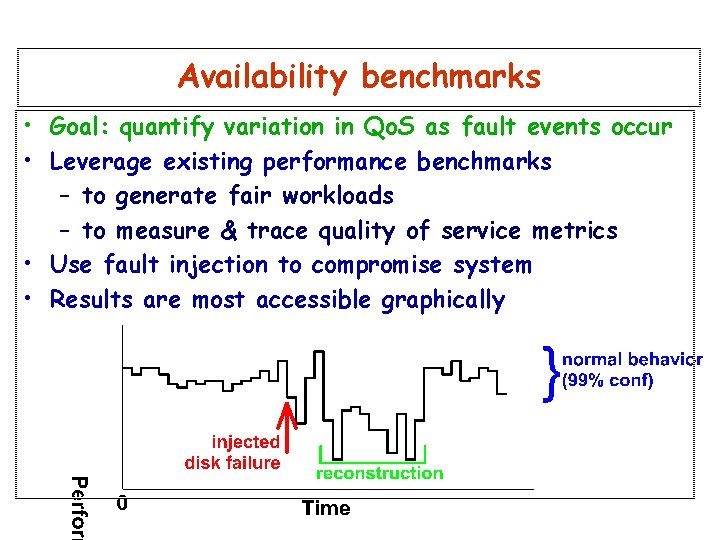

Availability benchmarks • Goal: quantify variation in Qo. S as fault events occur • Leverage existing performance benchmarks – to generate fair workloads – to measure & trace quality of service metrics • Use fault injection to compromise system • Results are most accessible graphically Slide 21

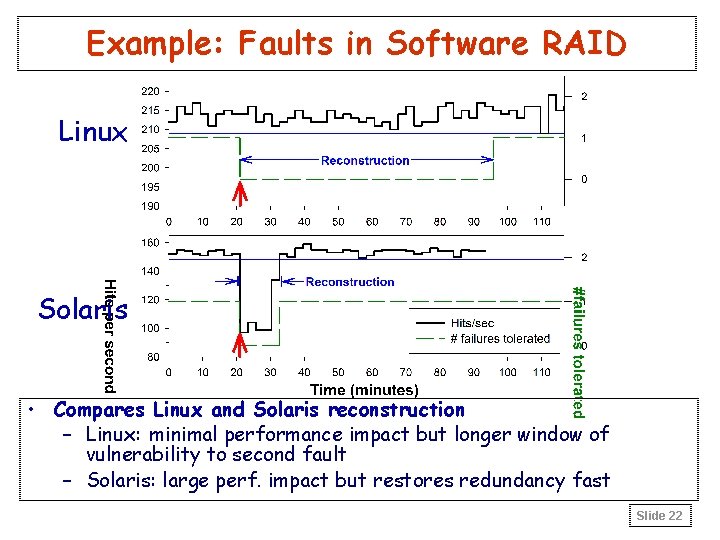

Example: Faults in Software RAID Linux Solaris • Compares Linux and Solaris reconstruction – Linux: minimal performance impact but longer window of vulnerability to second fault – Solaris: large perf. impact but restores redundancy fast Slide 22

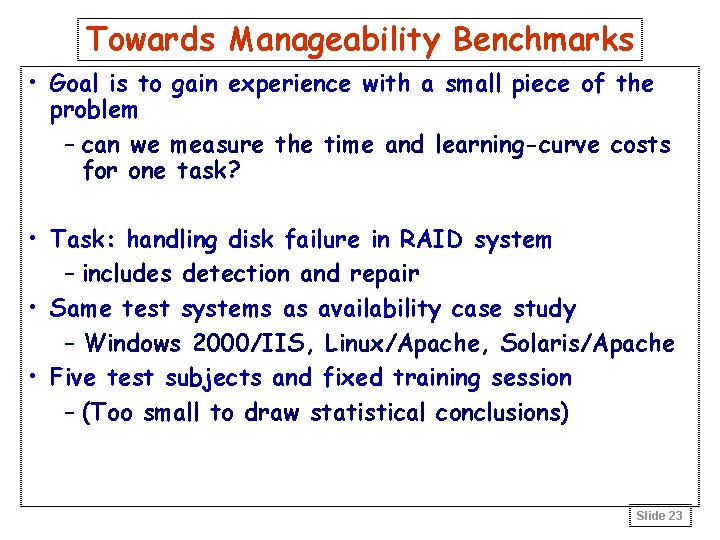

Towards Manageability Benchmarks • Goal is to gain experience with a small piece of the problem – can we measure the time and learning-curve costs for one task? • Task: handling disk failure in RAID system – includes detection and repair • Same test systems as availability case study – Windows 2000/IIS, Linux/Apache, Solaris/Apache • Five test subjects and fixed training session – (Too small to draw statistical conclusions) Slide 23

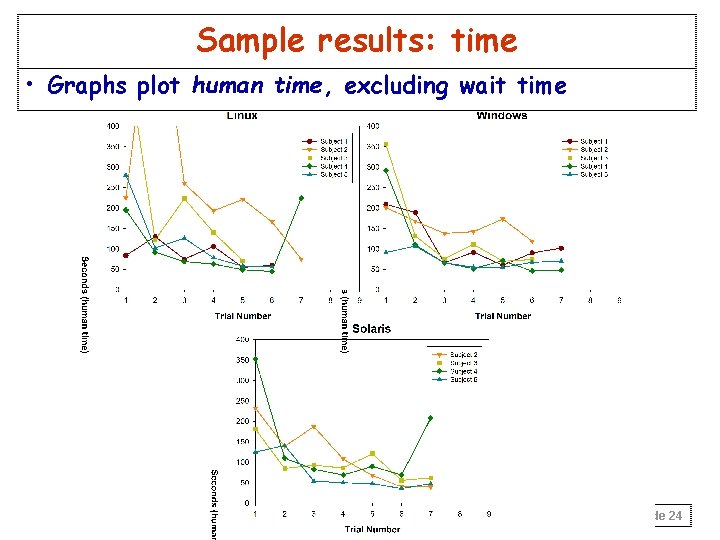

Sample results: time • Graphs plot human time, excluding wait time Slide 24

Analysis of time results • Rapid convergence across all OSs/subjects – despite high initial variability – final plateau defines “minimum” time for task – plateau invariant over individuals/approaches • Clear differences in plateaus between OSs – Solaris < Windows < Linux » note: statistically dubious conclusion given sample size! Slide 25

ISTORE Status • ISTORE Hardware – All 80 Nodes (boards) manufactured – PCB backplane: in layout – Finish 80 node system: December 2000 • Software – 2 -node system running -- boots OS – Diagnostic Processor SW and device driver done – Network striping done; fault adaptation ongoing – Load balancing for performance heterogeneity done • Benchmarking – Availability benchmark example complete – Initial maintainability benchmark complete, revised strategy underway Slide 26

BACKUP SLIDES IRAM Slide 27

IRAM Latency Advantage • 1997 estimate: 5 -10 x improvement – No parallel DRAMs, memory controller, bus to turn around, SIMM module, pins… – 30 ns for IRAM (or much lower with DRAM redesign) – Compare to Alpha 600: 180 ns for 128 b; 270 ns for 512 b • 2000 estimate: 5 x improvement – IRAM memory latency is 25 ns for 256 bits, fixed pipeline delay – Alpha 4000/4100: 120 ns Slide 28

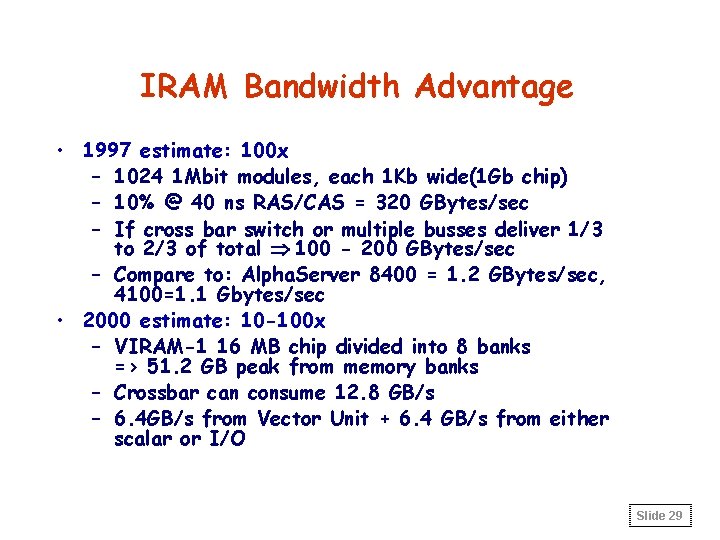

IRAM Bandwidth Advantage • 1997 estimate: 100 x – 1024 1 Mbit modules, each 1 Kb wide(1 Gb chip) – 10% @ 40 ns RAS/CAS = 320 GBytes/sec – If cross bar switch or multiple busses deliver 1/3 to 2/3 of total Þ 100 - 200 GBytes/sec – Compare to: Alpha. Server 8400 = 1. 2 GBytes/sec, 4100=1. 1 Gbytes/sec • 2000 estimate: 10 -100 x – VIRAM-1 16 MB chip divided into 8 banks => 51. 2 GB peak from memory banks – Crossbar can consume 12. 8 GB/s – 6. 4 GB/s from Vector Unit + 6. 4 GB/s from either scalar or I/O Slide 29

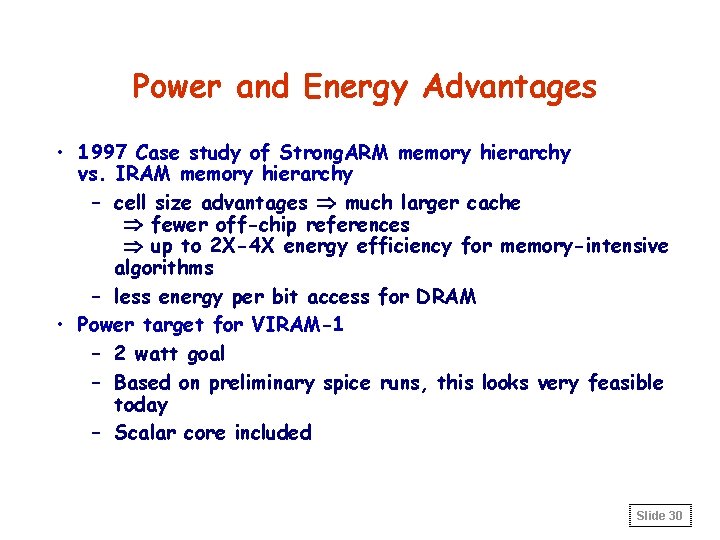

Power and Energy Advantages • 1997 Case study of Strong. ARM memory hierarchy vs. IRAM memory hierarchy – cell size advantages Þ much larger cache Þ fewer off-chip references Þ up to 2 X-4 X energy efficiency for memory-intensive algorithms – less energy per bit access for DRAM • Power target for VIRAM-1 – 2 watt goal – Based on preliminary spice runs, this looks very feasible today – Scalar core included Slide 30

Summary • IRAM takes advantage of high on-chip bandwidth • Vector IRAM ISA utilizes this bandwidth – Unit, strided, and indexed memory access patterns supported – Exploits fine-grained parallelism, even with pointer chasing • Compiler – Well-understood compiler model, semi-automatic – Still some work on code generation quality • Application benchmarks – Compiled and hand-coded – Include FFT, SVD, MVM, sparse MVM, and other kernels used in image and signal processing Slide 31

- Slides: 31