INVERTEBRATE MORPHOLOGY LIVING SYSTEMS Lect 1 2 They

INVERTEBRATE MORPHOLOGY LIVING SYSTEMS Lect 1 +2

They. say of Scandinavian furniaire that 'good design is timeless -it is the product of evolution'. The student of other aspects of animal life would agree with this claim; adding that good design expresses aptness for function. Upon this point of view our survey of invertebrate biology is based. It recognizes that animals are constructed upon patterns of organization that have been tested and proved through immense periods of competition and differential survival. It presupposes, therefore, that the way in which animals function can only be understood in the light of their past history. Further, it recognizes that the animals that share our life today are not imperfect creations that would fit better into their environment if they had some of our own advantages.

. This organization is an expression of the properties of systems of carbon compounds, but this does not necessarily mean that life is no more than a fortuitous association of molecules, nor does it necessarily follow that the humanist is correct in supposing that 'man must rely only upon himself'. But it is at least certain that the activities of living organisms depend upon the operation of physical and chemical principles no different from those that govern the properties of non-living systems. A fundamental characteristic of living systems is that they carry on a continuous exchange of energy and materials with their environment; we say that they are open systems, involved in exchanges that are the driving force of the complex systems of chemical reactions that we call metabolism. One result of their metabolic activity is that they are able to build up some of the products of metabolism into the substance of their bodies, thereby providing for the replacement of worn-out material and for growth.

Indeed, no part of a living body escapes the consequences of this continuous flux. Studies with radioactive tracers have shown that even the molecules of apparently permanent, inert material, such as supporting skeletal structures, are steadily replaced by corresponding molecules taken into the body from outside. A further result of metabolic activity is the capacity for irritability and for adaptive response to stimulation, so that by movement of part or of the whole of the body the organism behaves in a way that makes possible a further consequence: the reproduction of the individual and hence the perpetuation of its species.

Reproduction depends upon the capacity of living systems for making copies of themselves-the process that we call replication. The perpetuation of the species, however, depends in the long run upon occasional imperfections in the replication, and as a result of these the copy may differ from the parental form in certain respects. These differences, which we call mutations, are likely either to aid or to impede the adjustments of a particular organism to its environment. But the resources of the environment are not limitless, so that the maintenance and growth of organisms involves competition between them for limited supplies of materials. Organisms tend by their own activities to extend the range of their distribution and thus to exploit their environment to the limits of their capacities.

Populations which develop mutations that aid such extension will probably be more successful in this competitive exploitation. They will tend to survive and reproduce at the expense of other populations, a consequence that is the basis of the process that we call natural selection. Thus we conceive the relations between living material and its environment to have been continuously moulded, with the resulting production of organisms that are ever more complex and ever more efficient in the exploitation of the environment. This is what we call evolution, which we see as a continuous sequence of change leading from the simplest forms of life to the most complex.

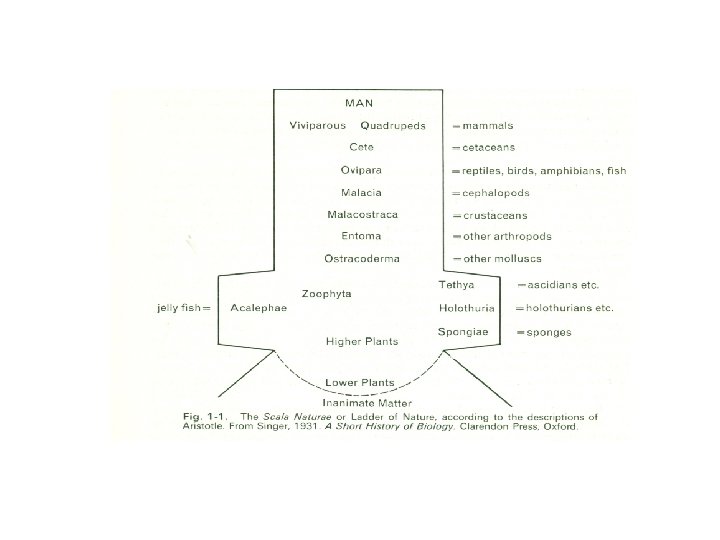

This concept of levels of complexity may seem self -evident to even the most superficial observer of animal life, yet it deserves some attention here, for it is not easy to translate it into more concrete terms. An early expression of it, and one that has powerfully influenced man's approach to other animals, is seen in Aristotle's Scala Naturae (Fig. 1 -1), or Ladder of ature.

According to his interpretation: nature proceeds little by little from things lifeless to animal life in such a way that it is impossible to determine the exact line of demarcation, nor on which side thereof an intermediate form should lie. Thus, next after lifeless things in the upward scale comes the plant, and of plants one will differ from another as to its amount of apparent vitality; and, in a word, the whole genus of plants, whilst it is devoid of life as compared with an animal, is endowed with life as compared with other corporeal entities. Indeed, as we have just remarked, there is observed in plants a continuous scale of ascent towards the animal. . In regard to sensibility, some animals give no indication whatsoever of it, whilst others indicate it but indistinctly. Further, the substance of some of these intermediate creatures is fteshlike, as is the case with the so-called tethya [ascidians] and the acalephae [sea-anemones]; but the sponge is in every respect like a vegetable. And so throughout the entire animal scale there is a graduated differentiation in amount of vitality and in capacity for motion.

Aristotle's interpretation was not an evolutionary one in our modern use of the term, but it does carry a clear implication of relative status. We have been accustomed to place at the top of the ladder the evil, flesh-eating beast that Sartre finds in us. Once we accept this position, however, there remains an implied corollary that other animals are in some sense 'lower', and that the 'lowest' are those at the bottom of the ladder. We do, in fact, regularly speak of 'lower' and 'higher' animals, and because of this it is necessary to consider exactly what we mean by these terms concealed niches. Like the city financier in the garden, 'he looks importantly about him, while all the spring goes on without him'. Other animals may exploit their environment much more fully; perhaps because they possess devices that enable them to resist a wider range of stresses, or perhaps because they can sample a wider choice of food. These animals may be regarded as higher than those that lead more restricted lives.

Here we have another objective criterion, and an approach to an explanation of the biological significance of more complex organization. We have, too, an objective justification of the dominant status of man in the Scala Naturae. It can be justified by his ability to manipulate his environment to his own also by the flexibility of his behaviour, and by the unique capacity of his nervous system, which results, among many other things, in making him the only animal that can scrutinize the rest of the animal kingdom in sufficient depth to be able to write books about it. Two other concepts may conveniently be mentioned here, since they are closely associated with this matter of status. In our comparisons of animals we customarily refer to them, or to the groups to which they belong, as being either 'primitive' or 'specialized'. By specialized we mean that they possess characters that tend to debar them from further evolutionary change. Primitive groups or primitive animals, by contrast, possess many characters that are theoretically capable of further change. For example, we shall speak of the nerve net as a primitive type of nervous system, because we can conceive it as the forerunner of the polarized and centralized type of nervous system of higher animals.

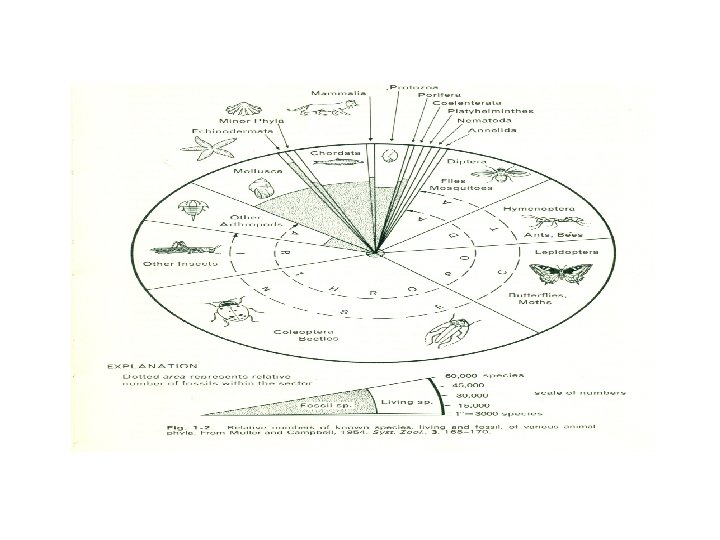

Finally, it is our common habit to speak of animals or groups as being 'successful' or 'unsuccessful'. These terms, like 'higher' and 'lower', are relative, and can only be usefully employed if we provide ourselves with some objective standard. Since life is always a struggle, and the environment fundamentally hostile to its maintenance, it is fair to say that any group of animals that has survived at all is a successful one.

We shall see that animals must be organized so as to function and behave in a manner best calculated to ensure survival and reproduction. From this point of view some environments are more 'difficult' than others. The littoral zone of the sea, particularly that part of it below the tide marks, is easier to occupy than either dry land or the air, for example, and we shall find some reasons later why this is so. Exploitation of these more difficult environments has required the development of new devices that are not needed by animals living in the easier habitats: waterproofing for land, and wings for the air, are obvious examples. From this point of view animals living in more difficult environments may be regarded as higher animals; the possession by them of new and specialized devices is an objective criterion by which their rightful place on the ladder may be defined

But this analysis is not sufficient. Animals may inhabit very difficult environments, yet we may still feel that they are truly lower organisms. For example, life within the alimentary canal of another animal presents many problems. Few of us would expect to survive the experience of Jonah, but intestinal parasites regularly do so; yet this seems an inadequate reason for calling them higher animals. The important consideration here is that the possibilities of life on this planet may be exploited in many ways. One species may survive because it possesses a narrow and inflexible range of responses, allowing it to sample only a small fraction of the potential resources by which it is surrounded. Such an animal is Peripatus, which has reacted to the danger of desiccation on land by restricting itself to damp and seen in Fig. 1 -2, which shows the relative abundance of species in the major groups of animals. From this we can see, among other things, that the insects can be regarded as a highly successful group,

1 -2 ORIGIN OF LIVING SYSTEMS

The continuity of evolution is a fundamental element in the biologist's interpretation of the history of the earth. So much so, that he finds it logical to extend the concept to include also the origin of life from non-living material. At first sight it may seem formidably difficult to justify this extension. Living organisms are poised in such delicately balanced relationships with their environment that they are often said to present a highly improbable state of matter; a state of which it is therefore very difficult to conceive the origin. Until recently, indeed, the problem of the origin of life seemed to be beyond human understanding; but this was an over-pessimistic view, based, perhaps, upon the feeling that the facts of the situation were forever beyond our reach.

Early in the history of the earth the prevailing high temperature would have promoted the combination of some of the available elements. In this way there could have arisen ammonia, methane, and water vapour, which are believed to have been the first constituents of the earth's atmosphere. This belief is supported by the identification of these same substances in the atmospheres of the larger and more distant planets, where conditions are believed to have changed less rapidly than on the earth. In the course of time the earth would have cooled sufficiently for water to condense on its surface. This would initially have been fresh water, but material swept from the land would have slowly accumulated in it; thus the salt-water oceans would have formed. According to one view, it is in these that the earliest forms of life may have arisen, their origin dependent upon the solvent properties of water, and its consequent facilitation of chemical reactions.

The periods of time that we are discussing are so vast that our minds cannot clearly grasp their scale. For example, the oldest rocks may have appeared around 3, 000 million years ago; life began perhaps 1, 000 million years later. What can be grasped, however, is an hypothesis that was first clearly formulated by Oparin, and that is in line with this analysis of the sequence of chemical events. This hypothesis proposes that life in that inconceivably remote period must have originated in reducing conditions: the abundant supply of oxygen, on which it now depends, could not at that time have been available. In accordance with the methodology outlined above, this deduction has been tested by laboratory experiments, and the results of these tests are found to support this general analysis.

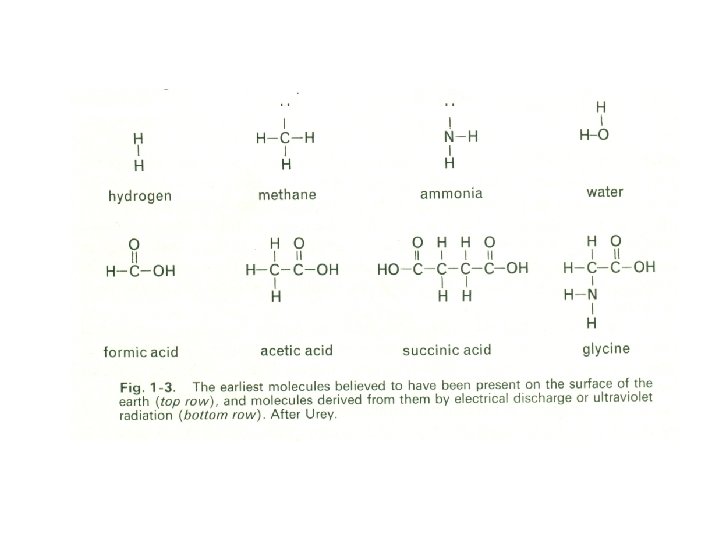

They have shown that organic material can actually be formed in such a reducing atmosphere, provided that an adequate supply of energy is available. In 1953 -54 it was shown by Miller, in what have now become classical experiments, that the passage of electrical discharges through a mixture of hydrogen, ammonia, methane, and water vapour could lead to the formation of the fundamental substrates required by living organisms (e. g. formic acid, acetic acid, succinic acid) and also to amino acids (Fig. 1 -3).

Moreover, amino acids have been polymerized to form peptide-like structures, under conditions comparable with those that might have existed during the early history of the earth. The appearance of these substances, which are the essential structural units of living material, may, therefore, have been inevitable and predictable during those remote times. Electrical energy was probably available, resulting from lightning displays such as are recorded as taking place today on Jupiter.

Ultraviolet light, however, would probably have been a more important energy source; it would not at that time have been reduced in intensity by the ozone layer that is formed now in our oxygen rich atmosphere, and it would have been continuously available.

Experiments similar to those of Miller, but using ultraviolet light as the energy source, regularly produce amino acids, provided that sufficient hydrogen is present to make the environment a reducing one. Of course, the production of amino acids and peptide chains is a very long way indeed from the establishment, maintenance, and replication of the organized patterns of living systems; further assumptions are clearly needed to develop this interpretation. We must assume that subsequently there was a building-up of increasingly complex molecular chains and of the molecular associations known as coacervates. This might have taken place in ancient seas, perhaps by the adsorption of the molecules onto mineral particles, We must further assume that these molecular aggregations developed the power of self-replication.

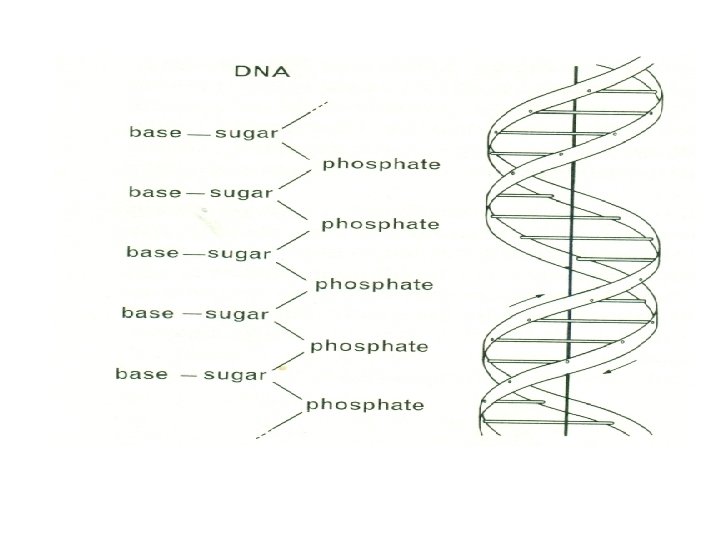

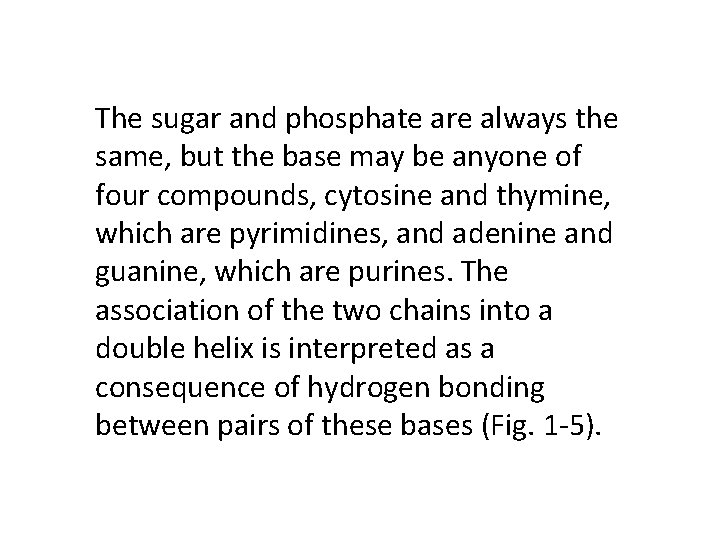

This replication may have been achieved through the well-known capacity of complex organic molecules to undergo polymerization, for the reproduction of organisms today depends upon the properties of the polymeric molecules of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). These giant molecules, with molecular weights of the order of 10 million, are believed, according to the now well-known interpretation that was originally advanced by Watson and Crick, to be organized as a double helix, the two molecular chains of this being coiled around a common axis (Fig. 1 -4). Each chain is thought to be composed of repeating units called nucleotides, which are formed of three constituents, a sugar (deoxyribose), a phosphate, and a nitrogenous base.

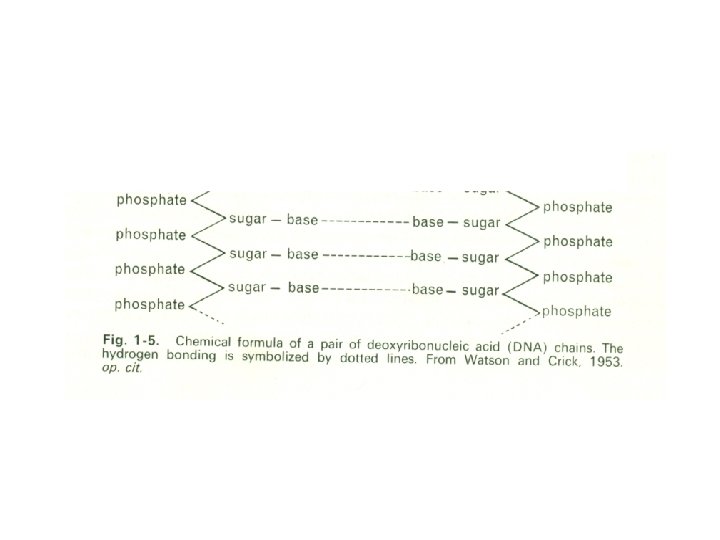

The sugar and phosphate are always the same, but the base may be anyone of four compounds, cytosine and thymine, which are pyrimidines, and adenine and guanine, which are purines. The association of the two chains into a double helix is interpreted as a consequence of hydrogen bonding between pairs of these bases (Fig. 1 -5).

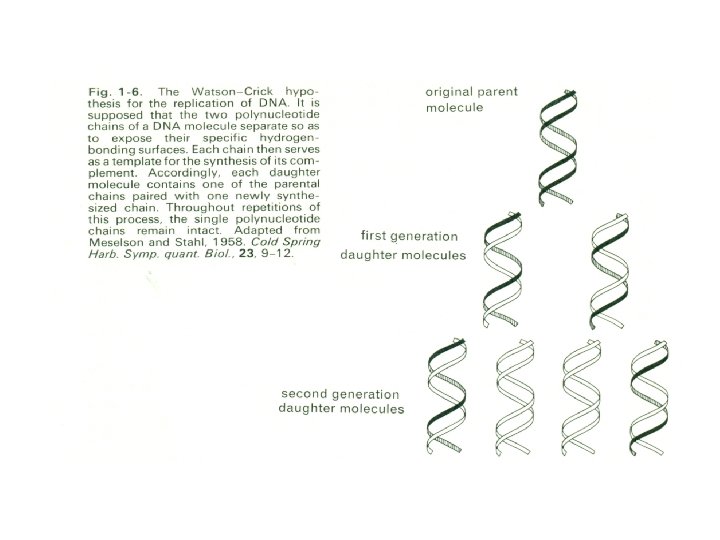

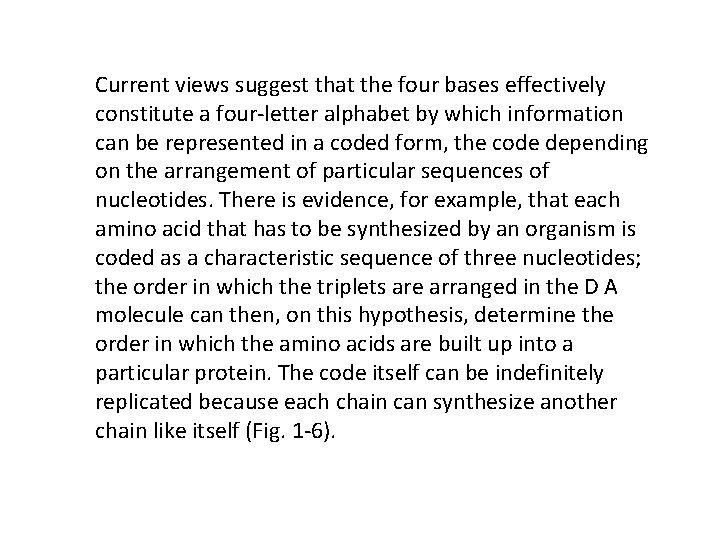

Current views suggest that the four bases effectively constitute a four-letter alphabet by which information can be represented in a coded form, the code depending on the arrangement of particular sequences of nucleotides. There is evidence, for example, that each amino acid that has to be synthesized by an organism is coded as a characteristic sequence of three nucleotides; the order in which the triplets are arranged in the D A molecule can then, on this hypothesis, determine the order in which the amino acids are built up into a particular protein. The code itself can be indefinitely replicated because each chain can synthesize another chain like itself (Fig. 1 -6).

The assumption that the conditions obtaining during the phase of chemical evolution could have led to the establishment of a substance with such remarkable properties as those attributed to DNA is an immense one. Yet we are helped to accept it by the knowledge that ribose, deoxyribose, adenine, and guanine have been produced in the laboratory in experiments similar in principle to those of Miller, while nucleotides have been polymerized to yield nucleic acids containing at least 200 residues. This, too, can be said in favour of it: in the reducing conditions then prevailing it would have been theoretically possible for organic molecules to accumulate and interact, whereas a similar accumulation could not occur today simply because the molecules would be oxidized by the atmosphere or broken down by living organisms. Moreover, the evolution of living material need not have been dependent upon entirely random processes, Calvin has suggested that simple inorganic compounds, or heavy metals, may have acted from an early stage as catalysts; they may thereby have served as driving forces that could have been favoured and canalized by natural selection,

EVOLUTION OF ENERGY RELATIONSHIPS

Whatever the means by which this organic complex evolved, its growth and replication would have required the supply of materials and energy that we have seen to be the foundation of living systems. We must assume, therefore, that in the primeral oceans there were other complex and energy-rich molecules that could be taken up into these systems, and that the latter could release and make use of the energy so obtained. This would have constituted the first appearance of metabolic processes, The metabolism of organisms as we know them today depends upon a very peculiar way of storing and transferring energy, and of releasing it in a form that is immediately available for use in biological processes, In principle, a large proportion of the energy released by the metabolic breakdown of organic compounds is taken up by adenosine diphosphate (ADP), which is thus transformed into adenosine triphosphate (ATP) , In due course this is broken down again by hydrolysis into ADP, the energy so released becoming available for some form or other of biological activity, Within these two compounds the energy is held in association with phosphate bonds. These, which are known as high-energy bonds, constitute one of the unique features of living material; in formal equations they are represented symbolically by curved lines: adenosine -®~®~® -+ adenosine -®~®+ HO®+free-energy change

We have seen that adenine can be formed in the laboratory in conditions analogous to those that might have existed during the earliest stages of the chemical phase of evolution. It is thus all the more significant that high-energy phosphate linkages are generated when ferrous iron is oxidized by hydrogen peroxide in the presence of orthophosphate. These conditions could probably have existed from a very early stage of chemical evolution, and may well have promoted the incorporation of these linkages into living systems. Thus we may think of the earliest forms of life, according to this analysis, as precariously evolving in a reducing atmosphere, and dependent upon energy that was already stored in the complex molecules of their environment.

Organisms that now obtain their energy by breaking down complex and energyrich carbon compounds taken in from their environment are known as heterotrophs. The earliest forms of anaerobic life that we have been postulating can therefore be termed primitive heterotrophs. Their emergence was a major achievement of chemical evolution, yet their future was not assured, for the reserves of energy stored in the molecules around them could not have lasted indefinitely. The molecules could not have been unlimited in abundance, and the supplies of them must sooner or later have been exhausted.

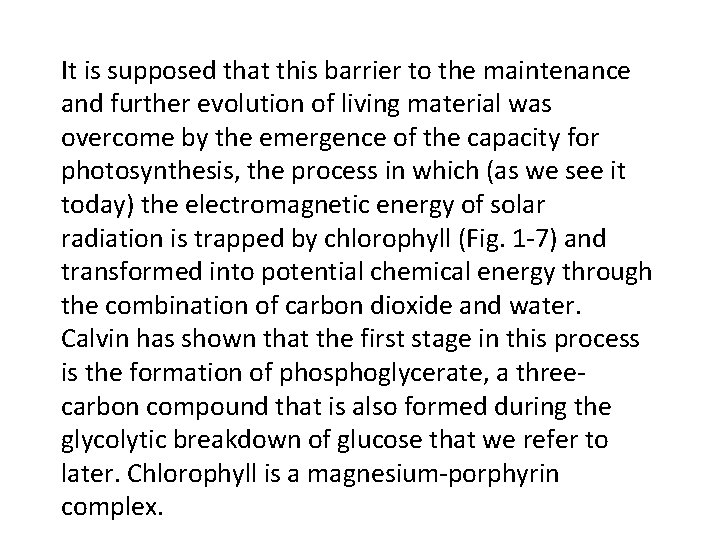

It is supposed that this barrier to the maintenance and further evolution of living material was overcome by the emergence of the capacity for photosynthesis, the process in which (as we see it today) the electromagnetic energy of solar radiation is trapped by chlorophyll (Fig. 1 -7) and transformed into potential chemical energy through the combination of carbon dioxide and water. Calvin has shown that the first stage in this process is the formation of phosphoglycerate, a threecarbon compound that is also formed during the glycolytic breakdown of glucose that we refer to later. Chlorophyll is a magnesium-porphyrin complex.

We shall see later that the production of porphyrins is so widespread in living organisms that we must suppose' these substances to have appeared at a very early stage of evolution. Their use in photosynthesis would have provided a continuous supply of energy-rich carbon compounds, so that living organisms needed no longer to depend upon ready-made sources of these in the environment

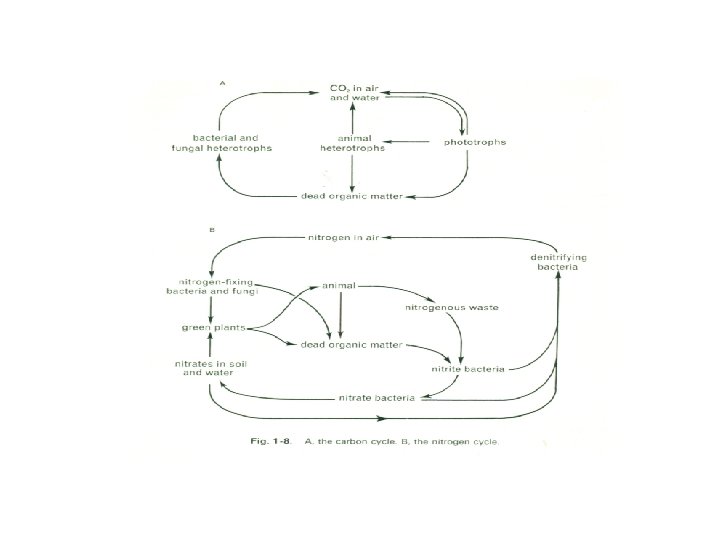

We have postulated a complex sequence of events. Whether or not it is correct, it is certain that in this or in some other way there were established the great cycles of flow of the chemical element that are vital to the maintenance of life, and that involve living organisms in complex webs of nutritional nterrelationships (Fig. 1 -8).

- Slides: 41