Introduction to Using Math ML Presented by Robert

Introduction to Using Math. ML Presented by: Robert Miner Director of New Product Development Bob Mathews Director of Training

What we’ll cover n Part I – Understanding Math. ML n n Overview of Math. ML Presentation and content markup Math. ML elements Building a Math. ML expression and inserting into HTML and XML pages. 2

What we’ll cover n n Part I – Understanding Math. ML Part II – Magic Incantations n n DOCTYPEs & MIME types Namespaces Object Tags and Processing Instructions Universal Math. ML Stylesheet 3

What we’ll cover n n n Part I – Understanding Math. ML Part II – Magic Incantations Part III – Tools n n n Design Science Web. EQ Design Science Math. Type with Math. Page technology Te. X 4 ht Amaya Now on to Part I – Understanding Math. ML 4

Overview of Math. ML n n The Mathematical Markup Language (Math. ML) was first published as a recommendation in April 1998. From the “Math Activity Statement” of the W 3 C Math Working Group: n “Designed as an XML application, Math. ML provides two sets of tags, one for the visual presentation of mathematics and the other associated with the meaning behind equations. ” 5

Overview of Math. ML n n The Mathematical Markup Language (Math. ML) was first published as a recommendation in April 1998. From the “Math Activity Statement” of the W 3 C Math Working Group: n “Designed as an XML application, Math. ML provides two sets of tags, one for the visual presentation of mathematics and the other associated with the meaning behind equations. ” 6

Overview of Math. ML n n The Mathematical Markup Language (Math. ML) was first published as a recommendation in April 1998. From the “Math Activity Statement” of the W 3 C Math Working Group: n n “…two sets of tags…” “Math. ML is not designed for people to enter by hand but specialized tools provide the means for typing in and editing mathematical expressions. ” 7

Overview of Math. ML n n The Mathematical Markup Language (Math. ML) was first published as a recommendation in April 1998. From the “Math Activity Statement” of the W 3 C Math Working Group: n n “…two sets of tags…” “Math. ML is not designed for people to enter by hand but specialized tools provide the means for typing in and editing mathematical expressions. ” 8

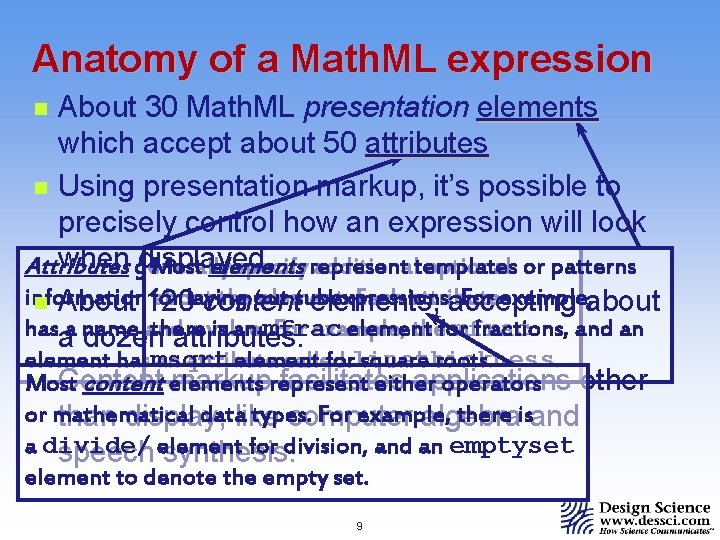

Anatomy of a Math. ML expression About 30 Math. ML presentation elements which accept about 50 attributes n Using presentation markup, it’s possible to precisely control how an expression will look when generally displayed. Most elements Attributes specify represent additionaltemplates optional or patterns for laying subexpressions. For example, about information about the out element. Each attribute n About 120 content elements, accepting there is an mfrac element fractions, and an hasaa name and a value. For example, thefor mfrac dozen attributes. element forlinethickness. square roots. element hasmsqrt an attribute called n Content markuprepresent facilitates applications Most content elements either operators other or mathematical datalike types. For example, there isand than display, computer algebra a divide/ for division, and an emptyset speech element synthesis. n element to denote the empty set. 9

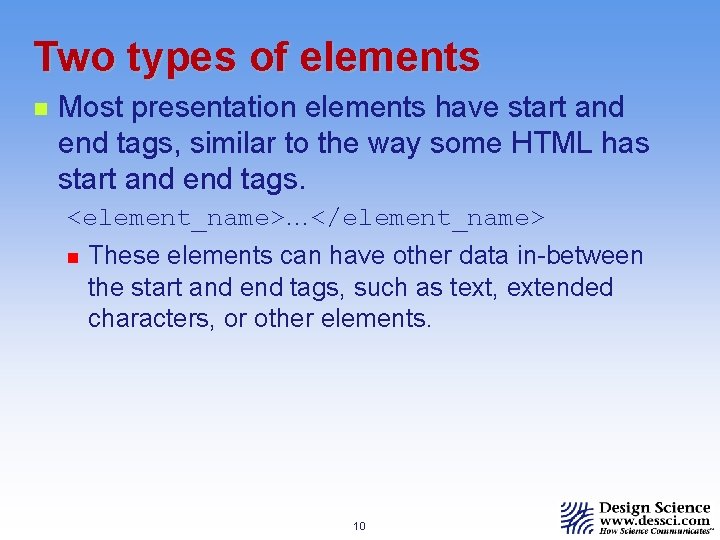

Two types of elements n Most presentation elements have start and end tags, similar to the way some HTML has start and end tags. <element_name>…</element_name> n These elements can have other data in-between the start and end tags, such as text, extended characters, or other elements. 10

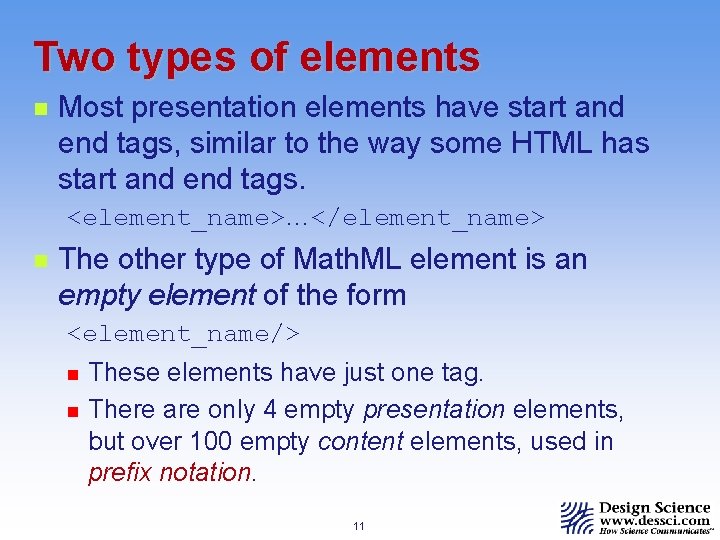

Two types of elements n Most presentation elements have start and end tags, similar to the way some HTML has start and end tags. <element_name>…</element_name> n The other type of Math. ML element is an empty element of the form <element_name/> n n These elements have just one tag. There are only 4 empty presentation elements, but over 100 empty content elements, used in prefix notation. 11

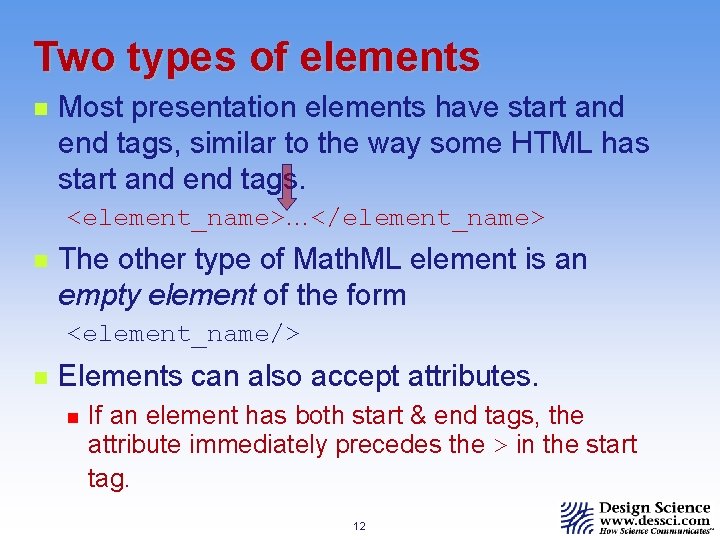

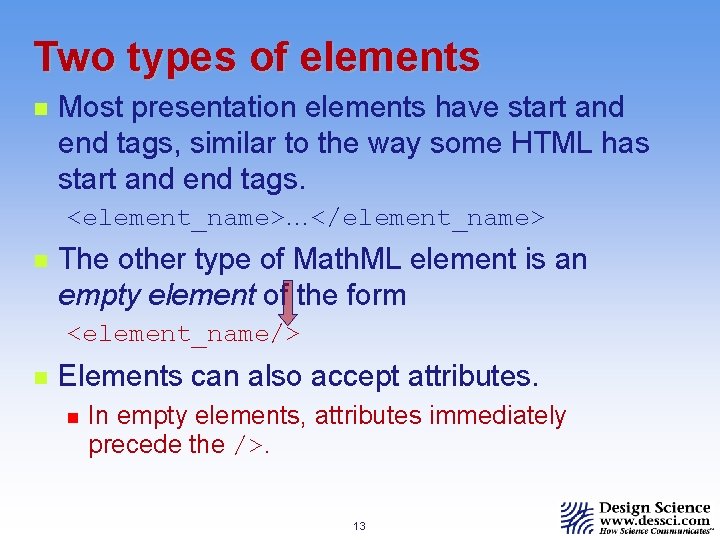

Two types of elements n Most presentation elements have start and end tags, similar to the way some HTML has start and end tags. <element_name>…</element_name> n The other type of Math. ML element is an empty element of the form <element_name/> n Elements can also accept attributes. n If an element has both start & end tags, the attribute immediately precedes the > in the start tag. 12

Two types of elements n Most presentation elements have start and end tags, similar to the way some HTML has start and end tags. <element_name>…</element_name> n The other type of Math. ML element is an empty element of the form <element_name/> n Elements can also accept attributes. n In empty elements, attributes immediately precede the />. 13

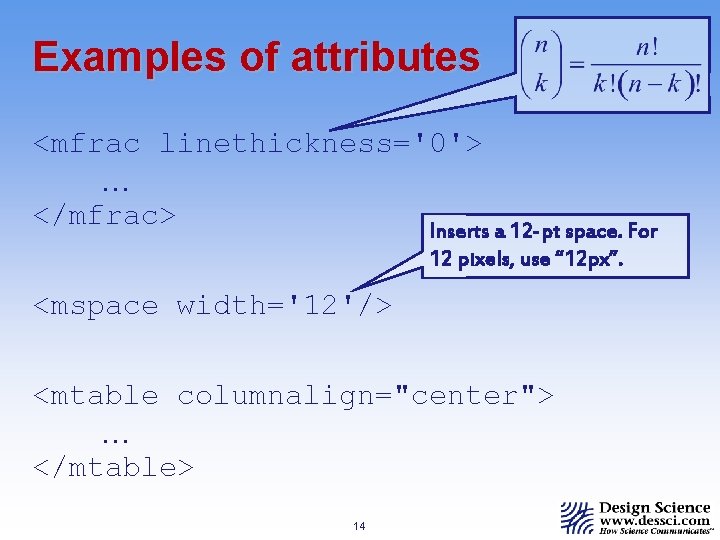

Examples of attributes <mfrac linethickness='0'> … </mfrac> Inserts a 12 -pt space. For 12 pixels, use “ 12 px”. <mspace width='12'/> <mtable columnalign="center"> … </mtable> 14

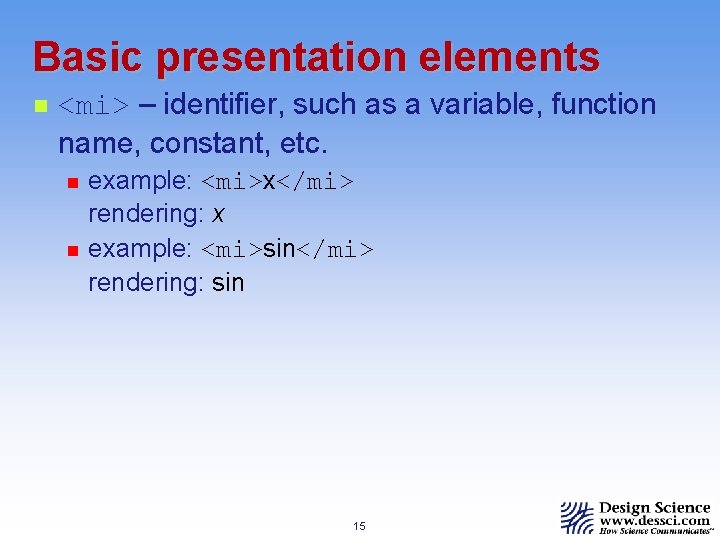

Basic presentation elements n <mi> – identifier, such as a variable, function name, constant, etc. n n example: <mi>x</mi> rendering: x example: <mi>sin</mi> rendering: sin 15

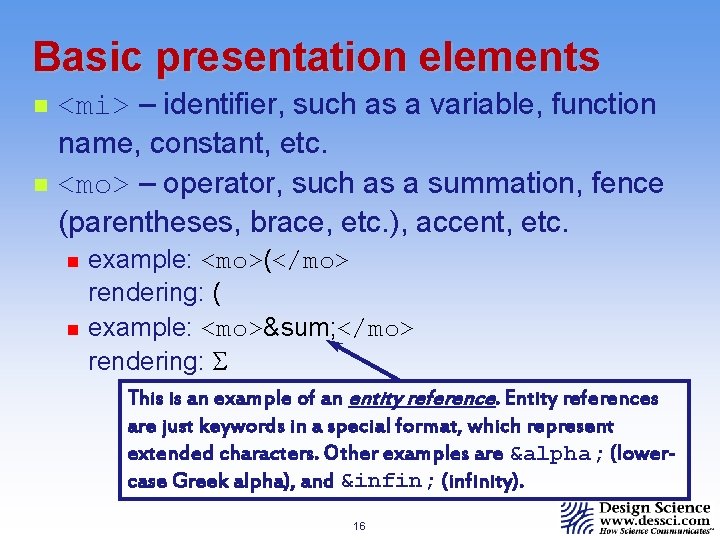

Basic presentation elements n n <mi> – identifier, such as a variable, function name, constant, etc. <mo> – operator, such as a summation, fence (parentheses, brace, etc. ), accent, etc. n n example: <mo>(</mo> rendering: ( example: <mo>∑ </mo> rendering: S This is an example of an entity reference. Entity references are just keywords in a special format, which represent extended characters. Other examples are α (lowercase Greek alpha), and ∞ (infinity). 16

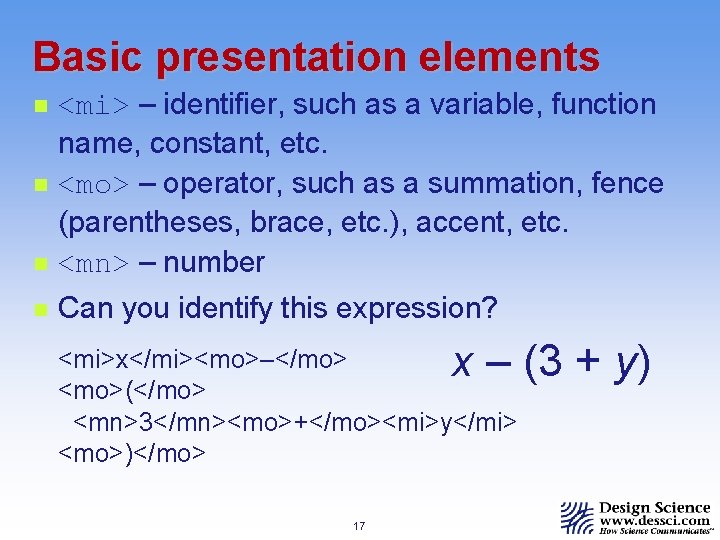

Basic presentation elements n <mi> – identifier, such as a variable, function name, constant, etc. <mo> – operator, such as a summation, fence (parentheses, brace, etc. ), accent, etc. <mn> – number n Can you identify this expression? n n x – (3 + y) <mi>x</mi><mo>–</mo> <mo>(</mo> <mn>3</mn><mo>+</mo><mi>y</mi> <mo>)</mo> 17

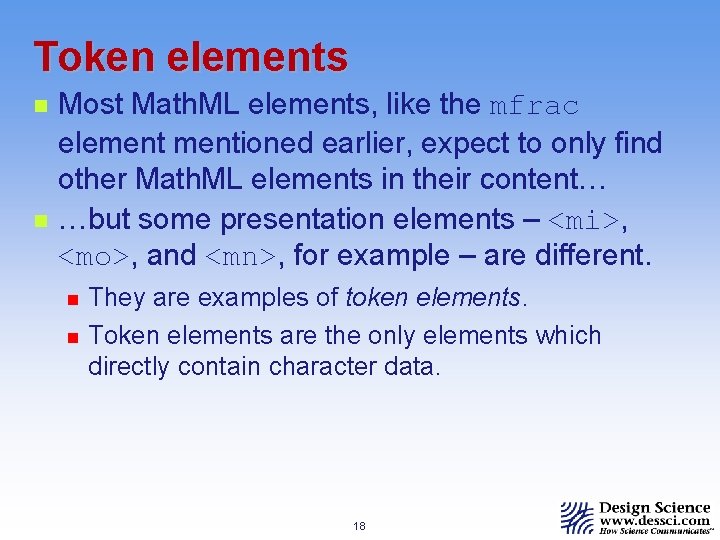

Token elements n n Most Math. ML elements, like the mfrac elementioned earlier, expect to only find other Math. ML elements in their content… …but some presentation elements – <mi>, <mo>, and <mn>, for example – are different. n n They are examples of token elements. Token elements are the only elements which directly contain character data. 18

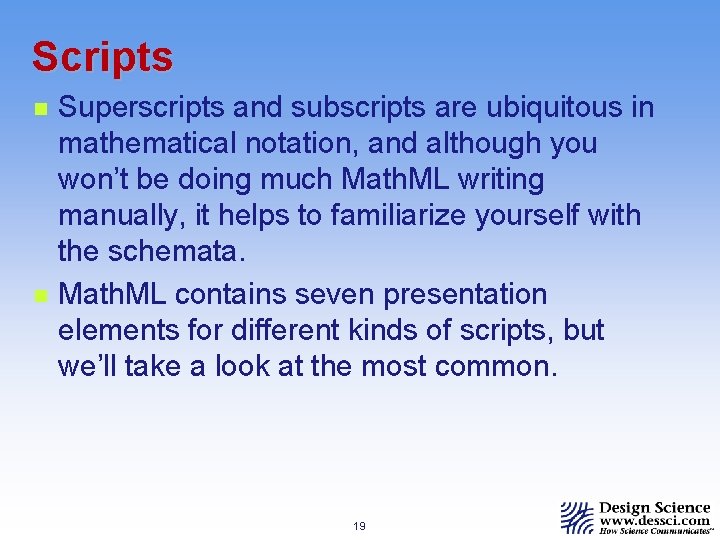

Scripts n n Superscripts and subscripts are ubiquitous in mathematical notation, and although you won’t be doing much Math. ML writing manually, it helps to familiarize yourself with the schemata. Math. ML contains seven presentation elements for different kinds of scripts, but we’ll take a look at the most common. 19

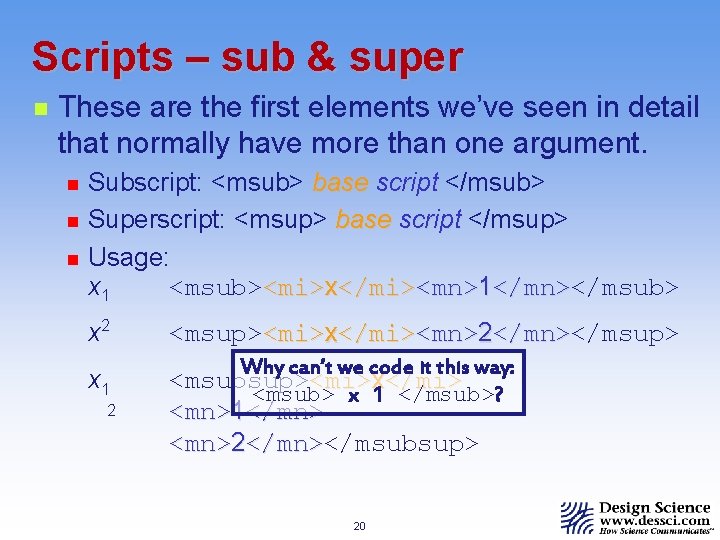

Scripts – sub & super n These are the first elements we’ve seen in detail that normally have more than one argument. n n n Subscript: <msub> base script </msub> Superscript: <msup> base script </msup> Usage: x 1 <msub><mi>x</mi><mn>1</mn></msub> </mn> x 2 <msup><mi>x</mi><mn>2</mn></msup> </mn> x 1 Why can’t we code it this way: <msubsup><mi>x</mi> <msub> x 1 </msub>? 2 <mn>1</mn> <mn>2</mn></msubsup> </mn> 20

Including Math. ML in your page n We need some way to identify the math markup to our browser, plug-in, or applet. n n Math. ML markup is inserted between <math> and </math> tags to distinguish Math. ML from other markup. Although most tags will differ from presentation markup to content markup, the <math> tag is common to both. 21

Coding simple expressions n As we stated at the beginning, it is not our goal in this tutorial to make you proficient at writing Math. ML. n n You’ll likely use a software product to produce the Math. ML markup rather than write it yourself. Our goal is to familiarize you enough with the Math. ML syntax and construction that you can read and understand a block of code, and can perhaps make changes to it by hand. 22

Coding simple expressions n n As we stated at the beginning, it is not our goal in this tutorial to make you proficient at writing Math. ML. That being the case, you know enough Math. ML now to try your hand at coding a couple of simple expressions… 23

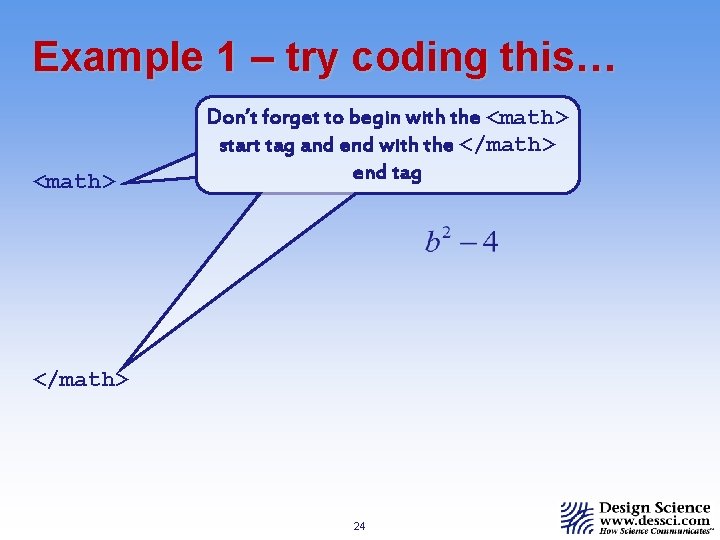

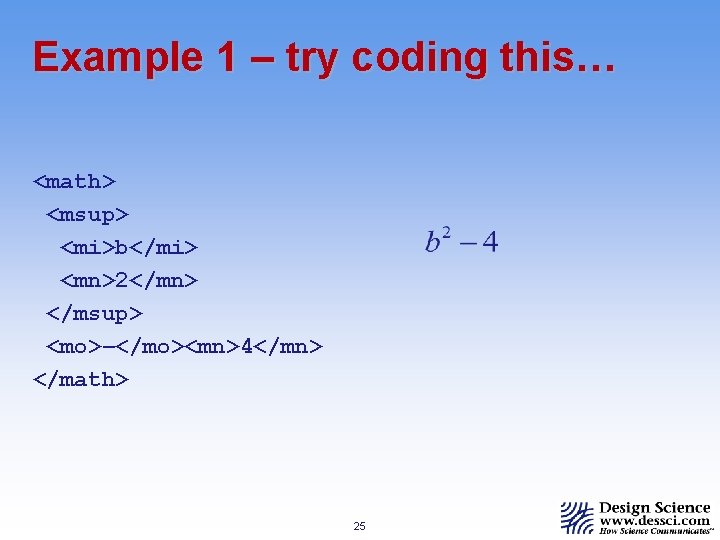

Example 1 – try coding this… <math> Don’t forget to begin with the <math> start tag and end with the </math> end tag </math> 24

Example 1 – try coding this… <math> <msup> <mi>b</mi> <mn>2</mn> </msup> <mo>–</mo><mn>4</mn> </math> 25

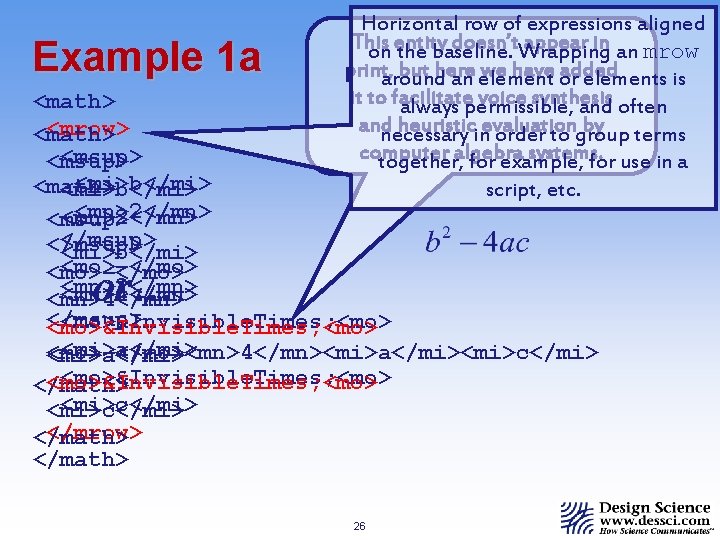

Example 1 a Horizontal row of expressions aligned This doesn’t. Wrapping appear in an mrow on entity the baseline. print, but here we have or added around an elements is it to facilitate voice synthesis always permissible, and often and heuristicinevaluation by terms necessary order to group computer systems. together, algebra for example, for use in a script, etc. <math> <mrow> <math> <msup> <mi>b</mi> <math> <mi>b</mi> <mn>2</mn> <msup> </msup> <mi>b</mi> <mo>–</mo> <mn>2</mn> <mn>4</mn> </msup> <mo>&Invisible. Times; <mo> <mi>a</mi> <mo>–</mo><mn>4</mn><mi>a</mi><mi>c</mi> <mi>a</mi> <mo>&Invisible. Times; <mo> </math> <mi>c</mi> </mrow> </math> or… 26

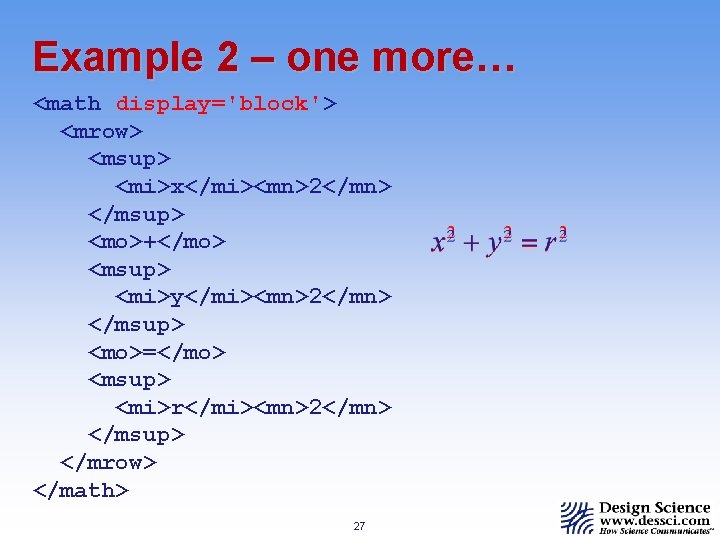

Example 2 – one more… <math display='block'> <mrow> <msup> <mi>x</mi><mn>2</mn> </msup> <mo>+</mo> <msup> <mi>y</mi><mn>2</mn> </msup> <mo>=</mo> <msup> <mi>r</mi><mn>2</mn> </msup> </mrow> </math> 27

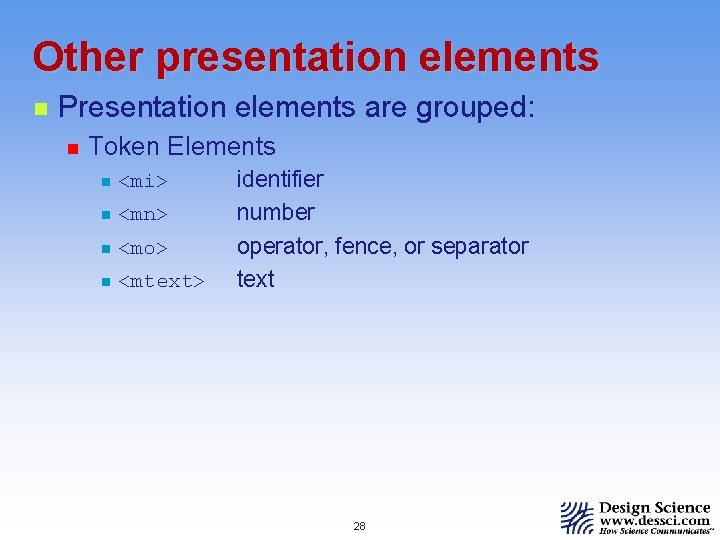

Other presentation elements n Presentation elements are grouped: n Token Elements n <mi> n <mn> n <mo> n <mtext> identifier number operator, fence, or separator text 28

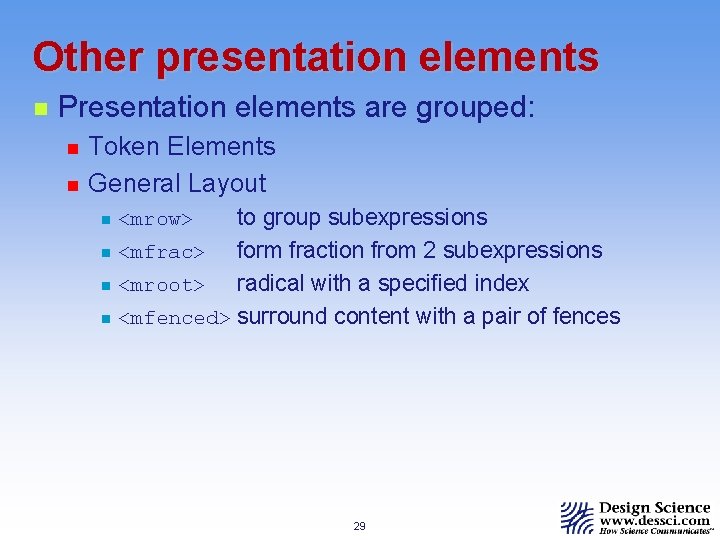

Other presentation elements n Presentation elements are grouped: n n Token Elements General Layout to group subexpressions n <mfrac> form fraction from 2 subexpressions n <mroot> radical with a specified index n <mfenced> surround content with a pair of fences n <mrow> 29

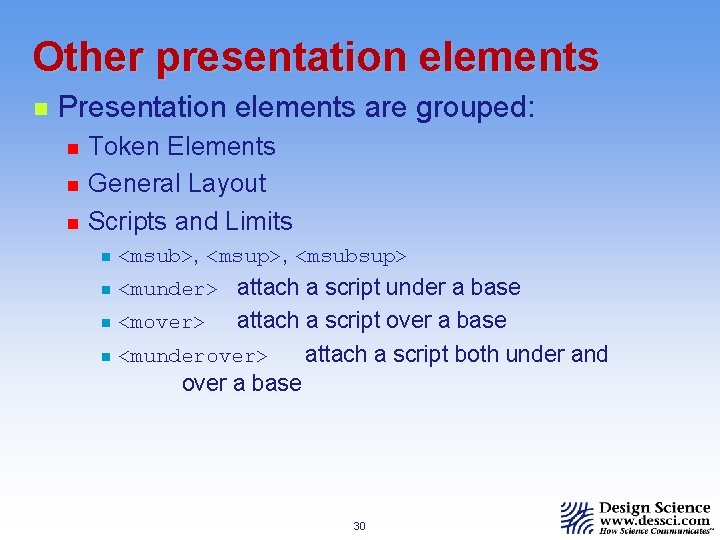

Other presentation elements n Presentation elements are grouped: n n n Token Elements General Layout Scripts and Limits n <msub>, <msup>, <msubsup> n <munder> attach a script under a base attach a script over a base n <munderover> attach a script both under and over a base n <mover> 30

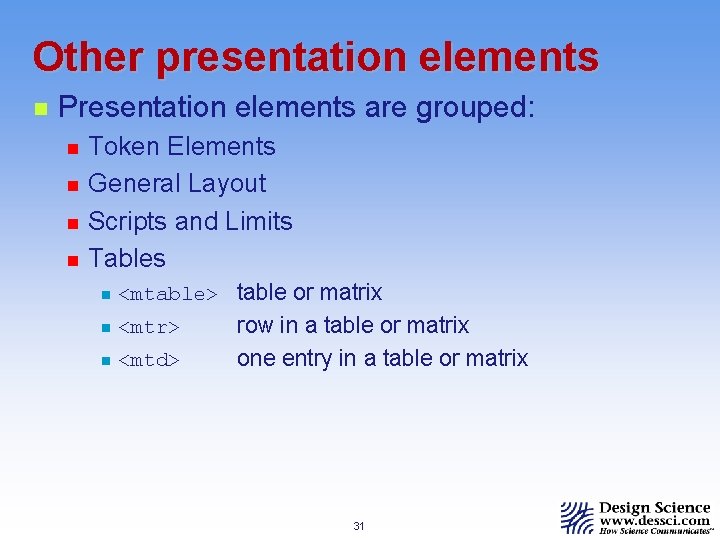

Other presentation elements n Presentation elements are grouped: n n Token Elements General Layout Scripts and Limits Tables n <mtable> table or matrix n <mtr> n <mtd> row in a table or matrix one entry in a table or matrix 31

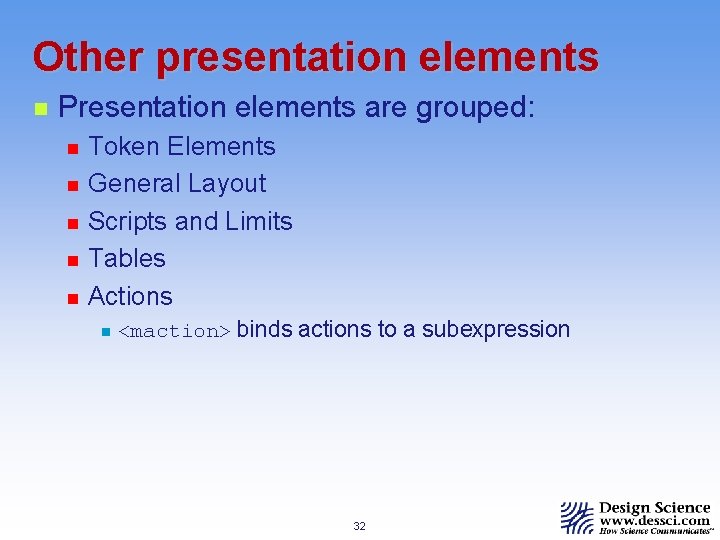

Other presentation elements n Presentation elements are grouped: n n n Token Elements General Layout Scripts and Limits Tables Actions n <maction> binds actions to a subexpression 32

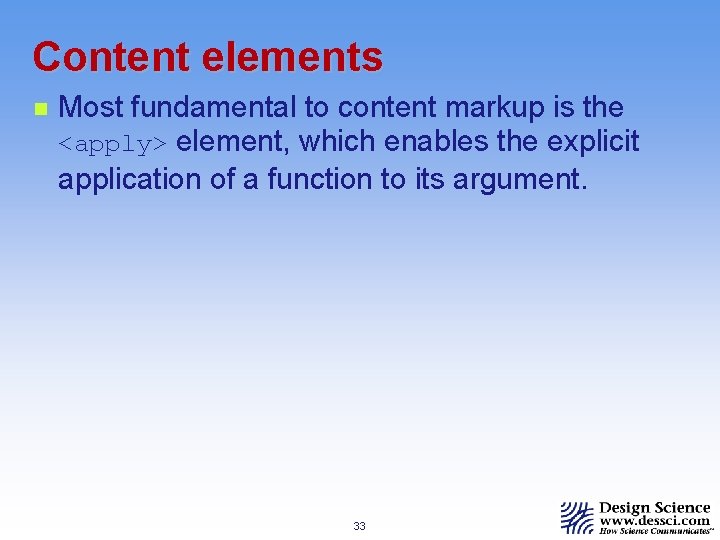

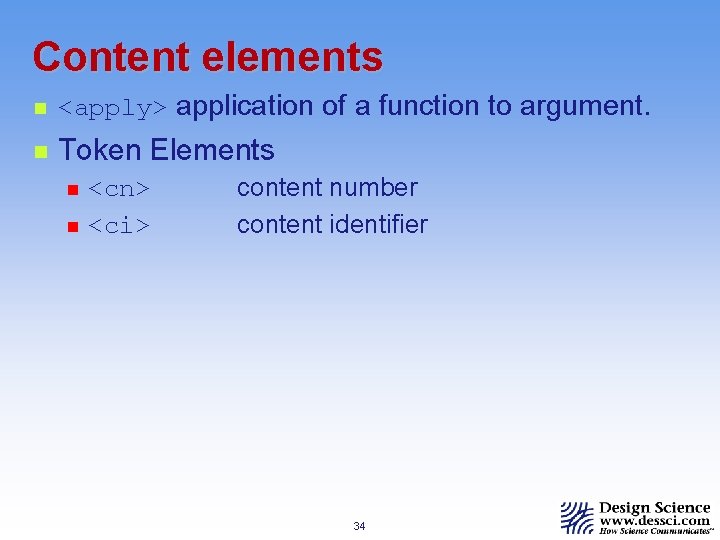

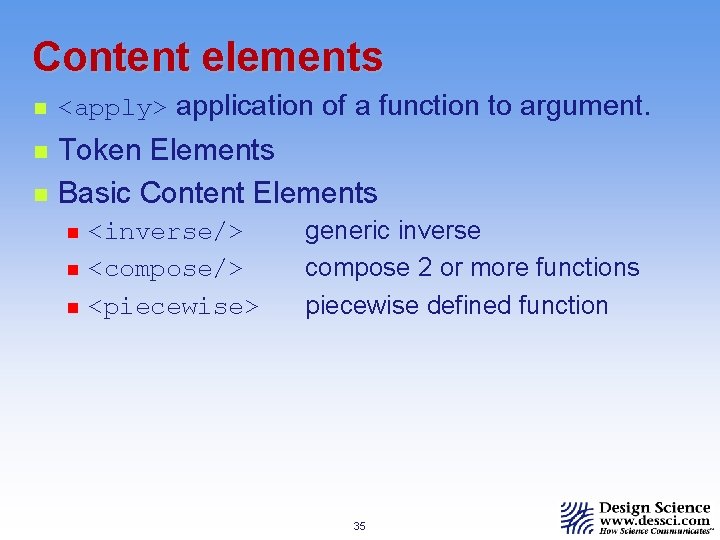

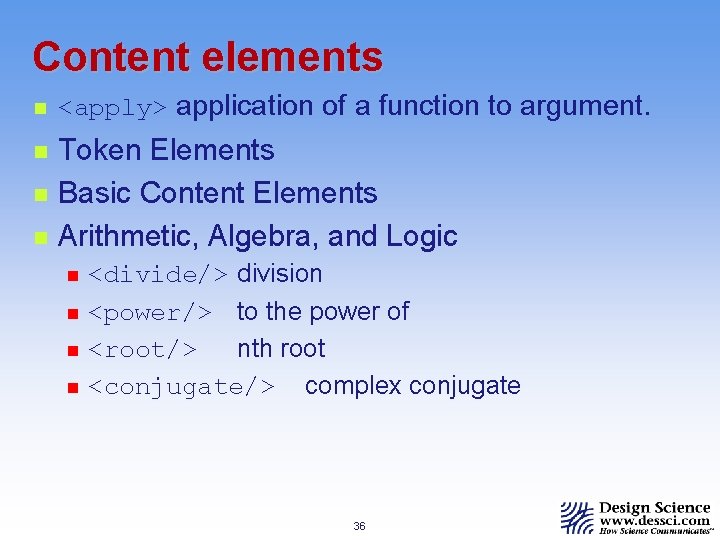

Content elements n Most fundamental to content markup is the <apply> element, which enables the explicit application of a function to its argument. 33

Content elements n <apply> application of a function to argument. n Token Elements n n <cn> <ci> content number content identifier 34

Content elements n n n <apply> application of a function to argument. Token Elements Basic Content Elements n n n <inverse/> <compose/> <piecewise> generic inverse compose 2 or more functions piecewise defined function 35

Content elements n n <apply> application of a function to argument. Token Elements Basic Content Elements Arithmetic, Algebra, and Logic n n <divide/> division <power/> to the power of <root/> nth root <conjugate/> complex conjugate 36

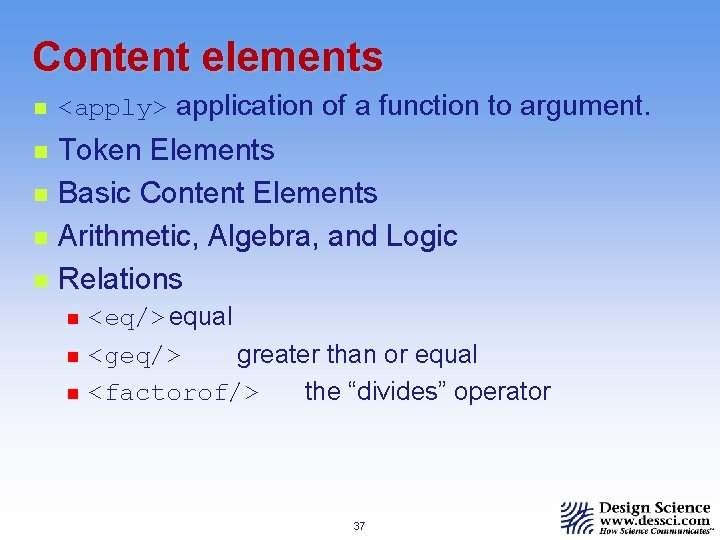

Content elements n n n <apply> application of a function to argument. Token Elements Basic Content Elements Arithmetic, Algebra, and Logic Relations n n n <eq/> equal <geq/> greater than or equal <factorof/> the “divides” operator 37

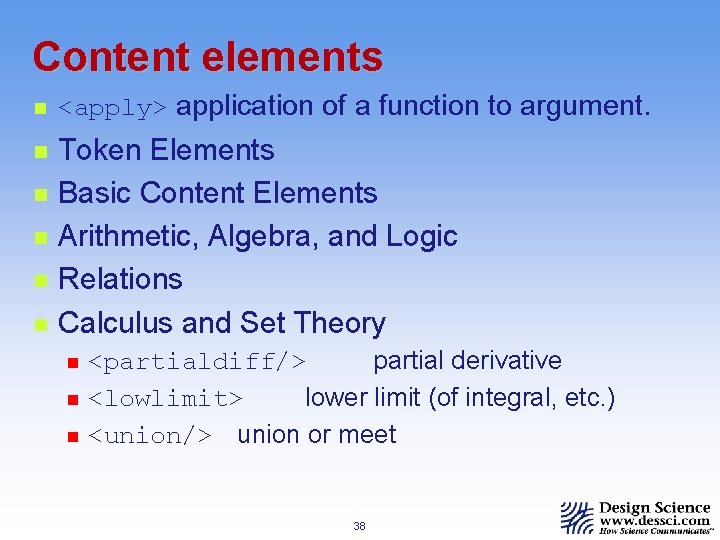

Content elements n n n <apply> application of a function to argument. Token Elements Basic Content Elements Arithmetic, Algebra, and Logic Relations Calculus and Set Theory n n n <partialdiff/> partial derivative <lowlimit> lower limit (of integral, etc. ) <union/> union or meet 38

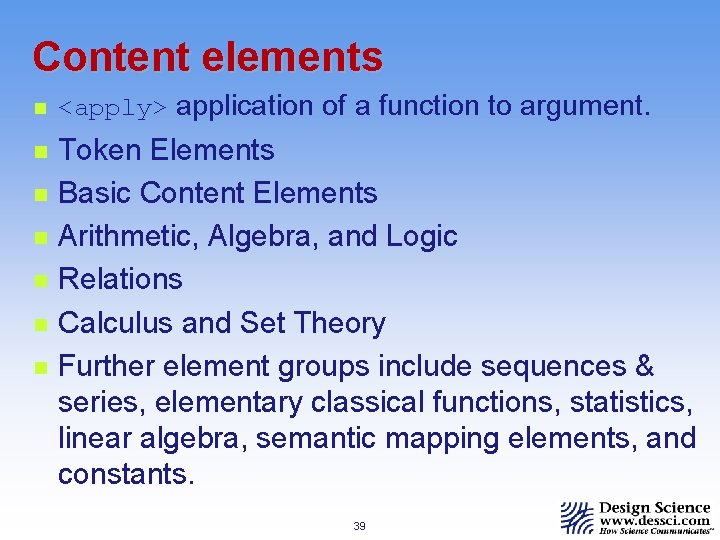

Content elements n n n n <apply> application of a function to argument. Token Elements Basic Content Elements Arithmetic, Algebra, and Logic Relations Calculus and Set Theory Further element groups include sequences & series, elementary classical functions, statistics, linear algebra, semantic mapping elements, and constants. 39

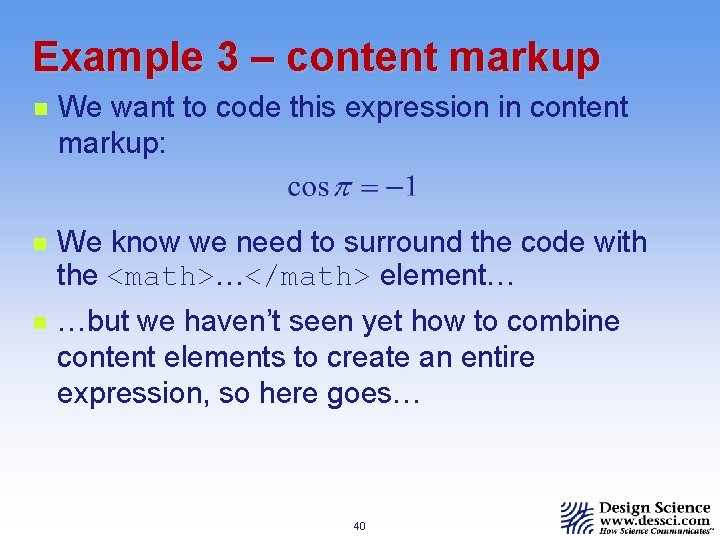

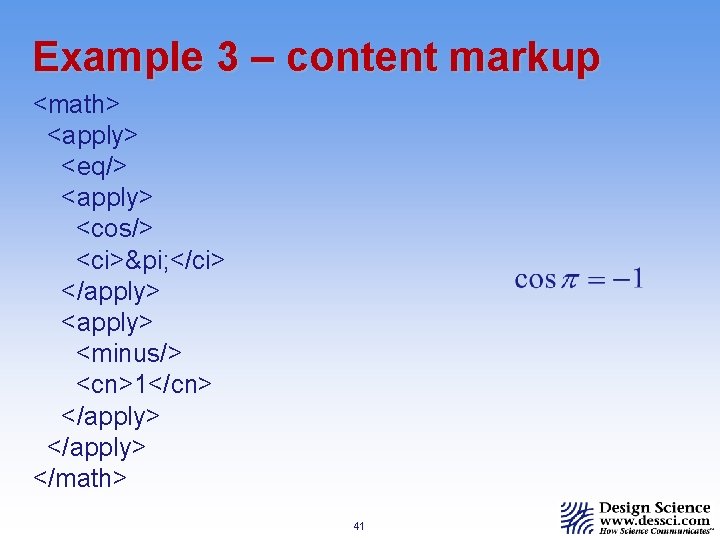

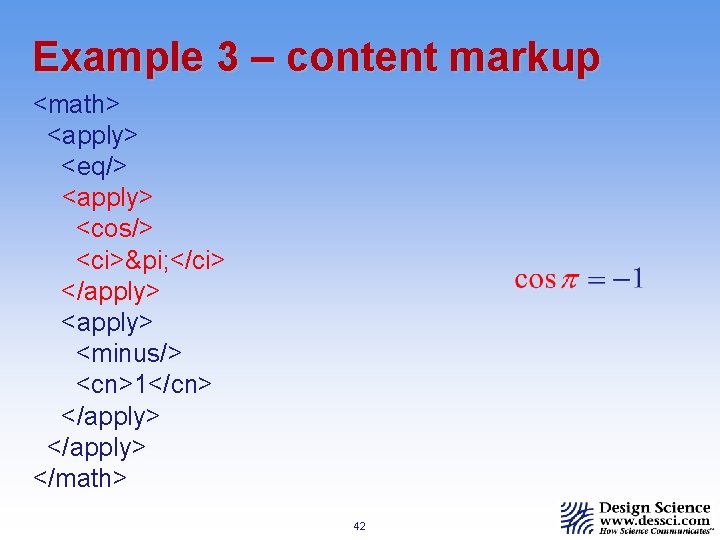

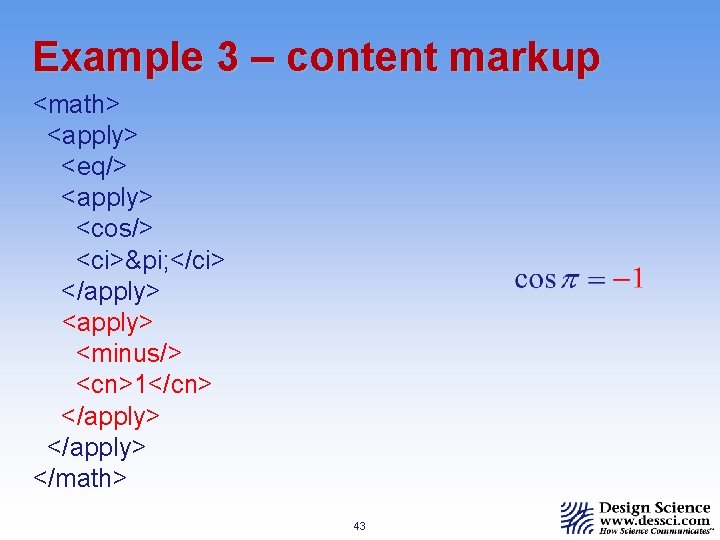

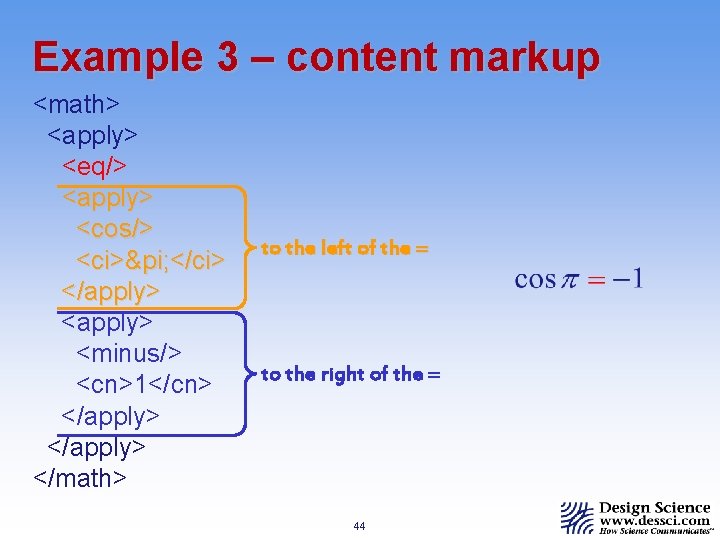

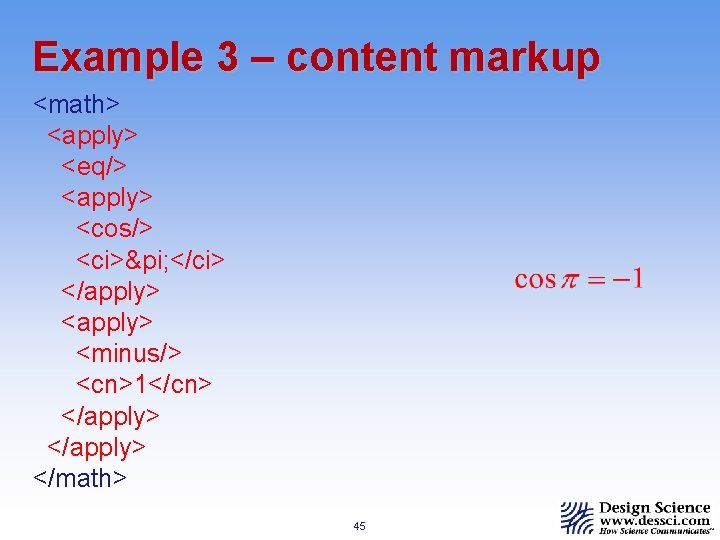

Example 3 – content markup n We want to code this expression in content markup: n We know we need to surround the code with the <math>…</math> element… n …but we haven’t seen yet how to combine content elements to create an entire expression, so here goes… 40

Example 3 – content markup <math> <apply> <eq/> <apply> <cos/> <ci>π </ci> </apply> <minus/> <cn>1</cn> </apply> </math> 41

Example 3 – content markup <math> <apply> <eq/> <apply> <cos/> <ci>π </ci> </apply> <minus/> <cn>1</cn> </apply> </math> 42

Example 3 – content markup <math> <apply> <eq/> <apply> <cos/> <ci>π </ci> </apply> <minus/> <cn>1</cn> </apply> </math> 43

Example 3 – content markup <math> <apply> <eq/> <apply> <cos/> <ci>π </ci> </apply> <minus/> <cn>1</cn> </apply> </math> to the left of the = to the right of the = 44

Example 3 – content markup <math> <apply> <eq/> <apply> <cos/> <ci>π </ci> </apply> <minus/> <cn>1</cn> </apply> </math> 45

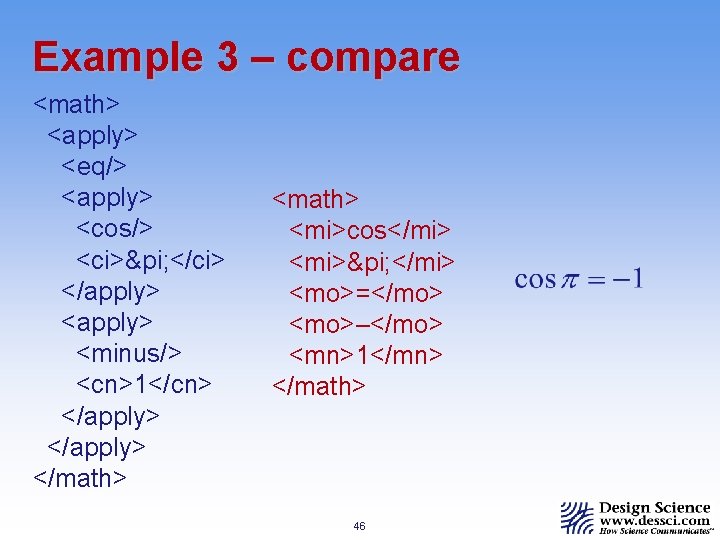

Example 3 – compare <math> <apply> <eq/> <apply> <cos/> <ci>π </ci> </apply> <minus/> <cn>1</cn> </apply> </math> <mi>cos</mi> <mi>π </mi> <mo>=</mo> <mo>–</mo> <mn>1</mn> </math> 46

Summary n Presentation markup is for describing math notation, and content markup is for describing mathematical objects and functions. n In presentation markup, expressions are built-up using layout schemata, which tell how to arrange their subexpressions (i. e. , mfrac or msup). 47

Summary n n Presentation markup…& content markup Math. ML elements either n n have start and end tags to enclose their content, or use a single empty tag. 48

Summary n n n Presentation markup…& content markup Math. ML elements… Attributes may be specified in a start or empty tag. n Attribute values must be enclosed in quotes. 49

Summary n n Presentation markup…& content markup Math. ML elements… Attributes … in a start or empty tag. All character data must be enclosed in token elements. 50

Summary n n n Presentation markup…& content markup Math. ML elements… Attributes … in a start or empty tag. All character data … token elements. Extended characters are encoded as entity references. 51

Summary n n n n Presentation markup…& content markup Math. ML elements… Attributes … in a start or empty tag. All character data … token elements. Extended characters as…entity references. We discussed other layout schemata – math, mfrac, mrow, etc. The next session of the tutorial will deal with displaying Math. ML in browsers. 52

Part II – Magic Incantations Triggering Math. ML rendering in browsers requires special declarations in the page. n n DOCTYPEs & MIME types Namespaces Object Tags and Processing Instructions Universal Math. ML Stylesheet 53

Which Browsers? n Internet Explorer (requires add-on software) The main choices are: Math. Player (IE 5. 5 or higher under Windows) n Techexplorer (IE 5 or higher, many platforms) n Java. Script/CSS (IE 6 Windows, others soon? ) n n Netscape (add-ons required before NS 7 PR 1) Some things to note: Math. ML doesn’t yet work on the Mac n The decision to include Math. ML isn’t final n 54

DOCTYPEs and MIME types n There are two ways browsers determine what kind of data needs to be displayed. n n Local files indicate their type with a filename extension (Windows, Unix) or extra data included in the file (Mac). Data coming over an http connection doesn’t have a filename. Thus, web servers include extra data about what kind of file is being sent. This extra data is called a MIME type. 55

DOCTYPEs and MIME types n n n Web servers generally use file extensions to pick the MIME type. This doesn’t always work… Netscape 7 is fanatical about using only the MIME type to determine how to display a document. Internet Explorer is extremely cavalier in using the MIME type, preferring to sniff inside the document to guess its type. 56

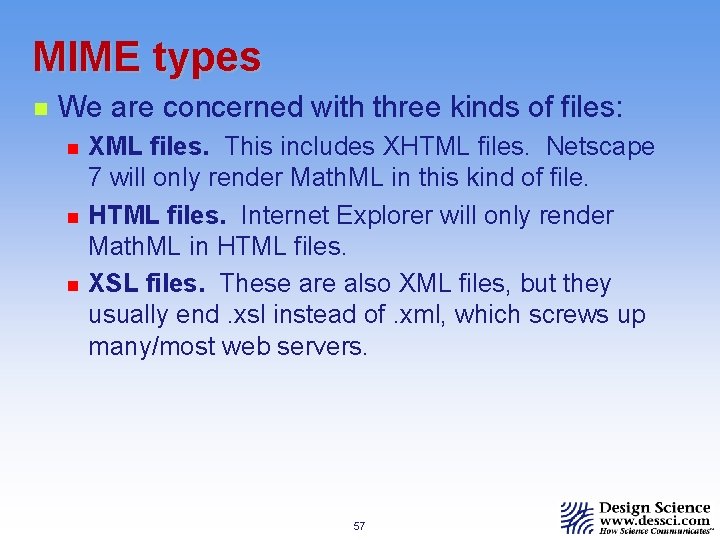

MIME types n We are concerned with three kinds of files: n n n XML files. This includes XHTML files. Netscape 7 will only render Math. ML in this kind of file. HTML files. Internet Explorer will only render Math. ML in HTML files. XSL files. These are also XML files, but they usually end. xsl instead of. xml, which screws up many/most web servers. 57

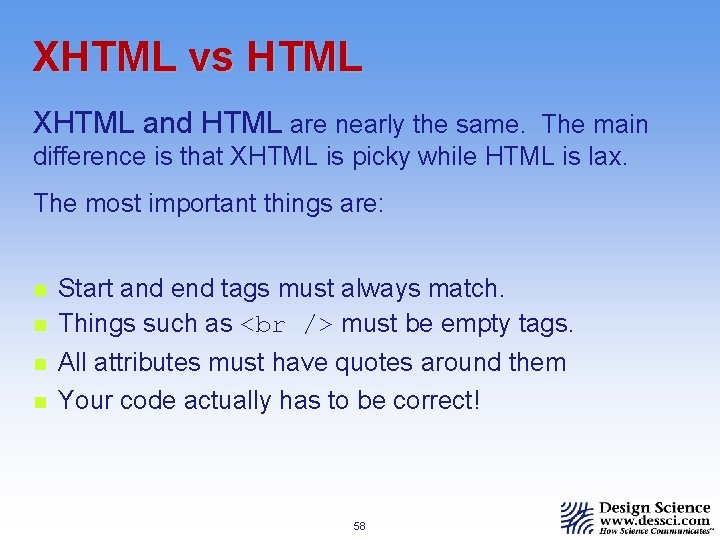

XHTML vs HTML XHTML and HTML are nearly the same. The main difference is that XHTML is picky while HTML is lax. The most important things are: n n Start and end tags must always match. Things such as must be empty tags. All attributes must have quotes around them Your code actually has to be correct! 58

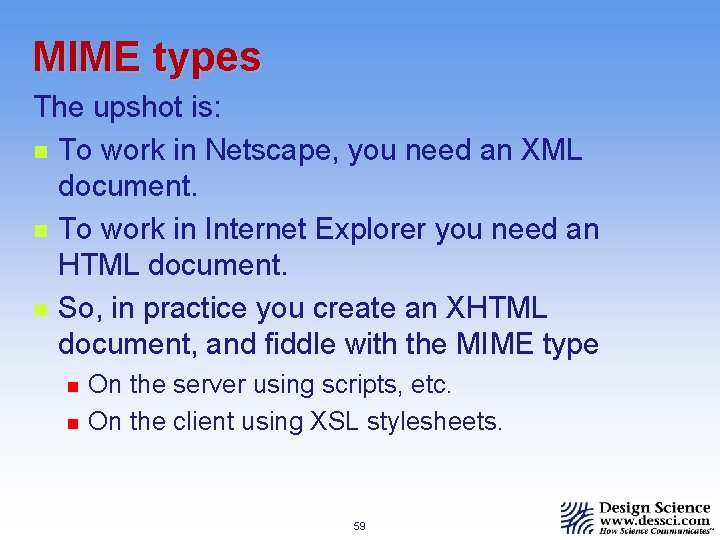

MIME types The upshot is: n To work in Netscape, you need an XML document. n To work in Internet Explorer you need an HTML document. n So, in practice you create an XHTML document, and fiddle with the MIME type n n On the server using scripts, etc. On the client using XSL stylesheets. 59

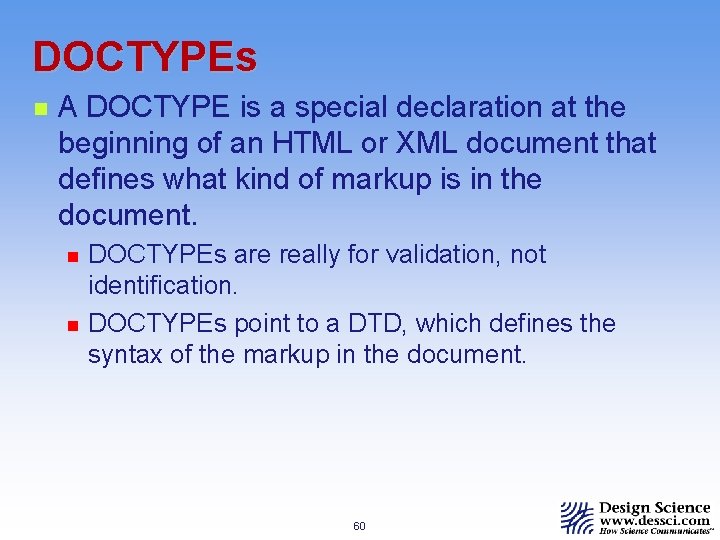

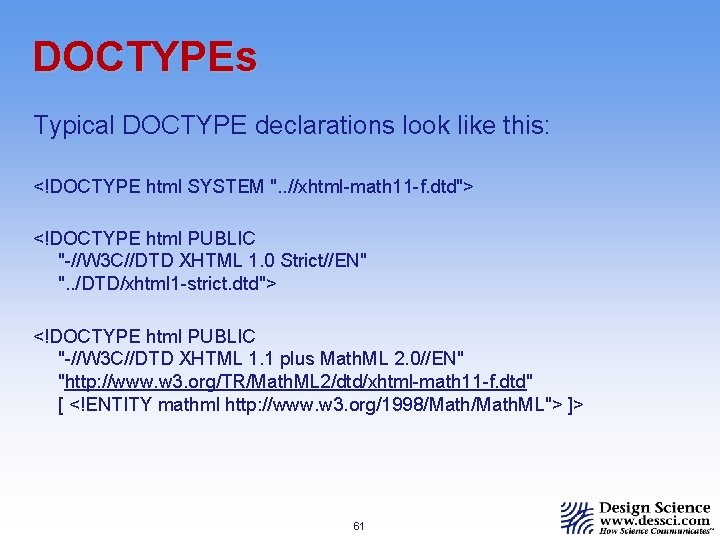

DOCTYPEs n A DOCTYPE is a special declaration at the beginning of an HTML or XML document that defines what kind of markup is in the document. n n DOCTYPEs are really for validation, not identification. DOCTYPEs point to a DTD, which defines the syntax of the markup in the document. 60

DOCTYPEs Typical DOCTYPE declarations look like this: <!DOCTYPE html SYSTEM ". . //xhtml-math 11 -f. dtd"> <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W 3 C//DTD XHTML 1. 0 Strict//EN" ". . /DTD/xhtml 1 -strict. dtd"> <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W 3 C//DTD XHTML 1. 1 plus Math. ML 2. 0//EN" "http: //www. w 3. org/TR/Math. ML 2/dtd/xhtml-math 11 -f. dtd" [ <!ENTITY mathml http: //www. w 3. org/1998/Math. ML"> ]> 61

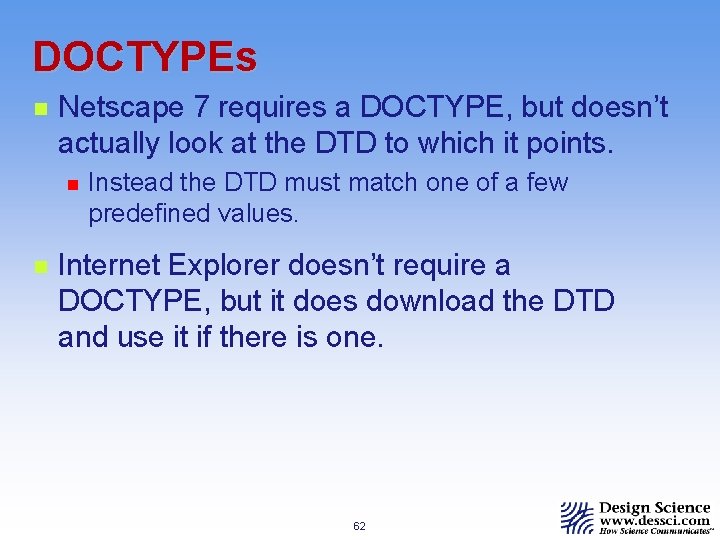

DOCTYPEs n Netscape 7 requires a DOCTYPE, but doesn’t actually look at the DTD to which it points. n n Instead the DTD must match one of a few predefined values. Internet Explorer doesn’t require a DOCTYPE, but it does download the DTD and use it if there is one. 62

DOCTYPEs The upshot is: n In your XHTML document, you put a DOCTYPE, and n The W 3 C Math WG pulls its hair out trying to make a DTD available that is both correct and works around the bugs in the IE parser. 63

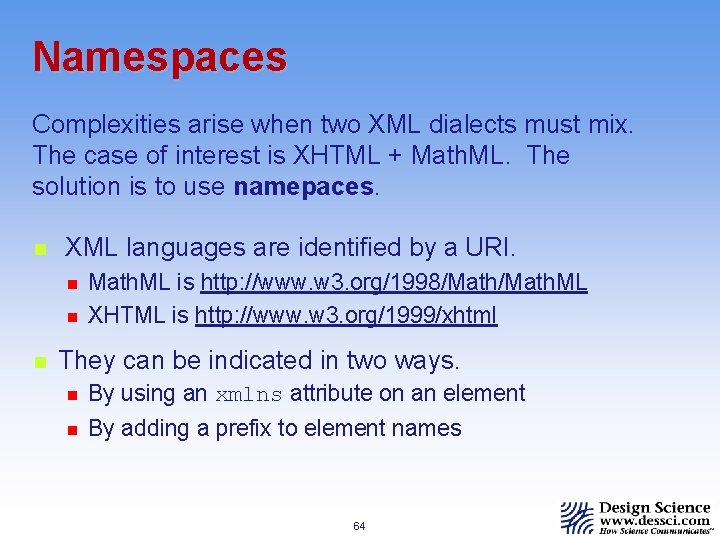

Namespaces Complexities arise when two XML dialects must mix. The case of interest is XHTML + Math. ML. The solution is to use namepaces. n XML languages are identified by a URI. n n n Math. ML is http: //www. w 3. org/1998/Math. ML XHTML is http: //www. w 3. org/1999/xhtml They can be indicated in two ways. n By using an xmlns attribute on an element n By adding a prefix to element names 64

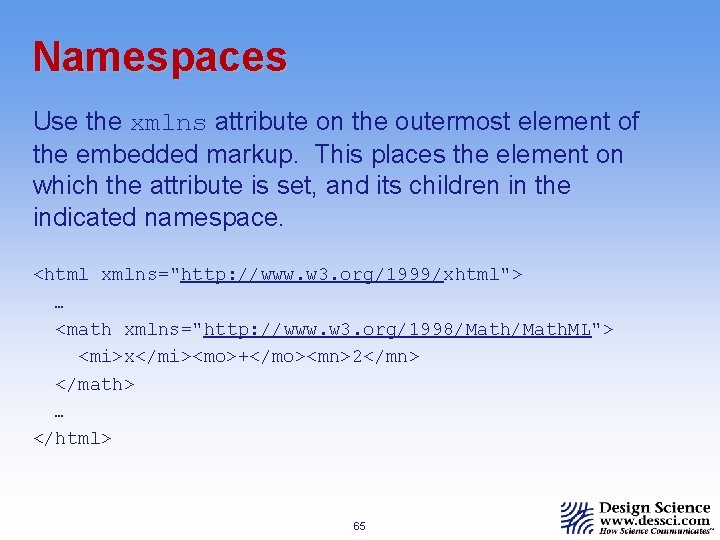

Namespaces Use the xmlns attribute on the outermost element of the embedded markup. This places the element on which the attribute is set, and its children in the indicated namespace. <html xmlns="http: //www. w 3. org/1999/xhtml"> … <math xmlns="http: //www. w 3. org/1998/Math. ML"> <mi>x</mi><mo>+</mo><mn>2</mn> </math> … </html> 65

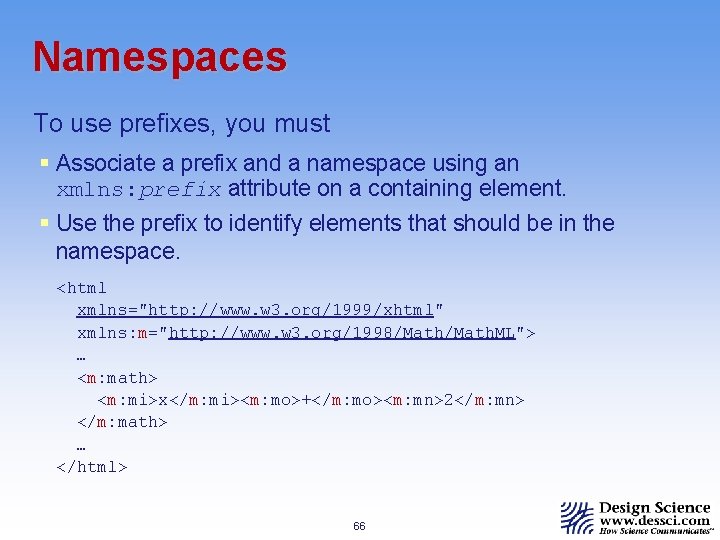

Namespaces To use prefixes, you must § Associate a prefix and a namespace using an xmlns: prefix attribute on a containing element. § Use the prefix to identify elements that should be in the namespace. <html xmlns="http: //www. w 3. org/1999/xhtml" xmlns: m="http: //www. w 3. org/1998/Math. ML"> … <m: math> <m: mi>x</m: mi><m: mo>+</m: mo><m: mn>2</m: mn> </m: math> … </html> 66

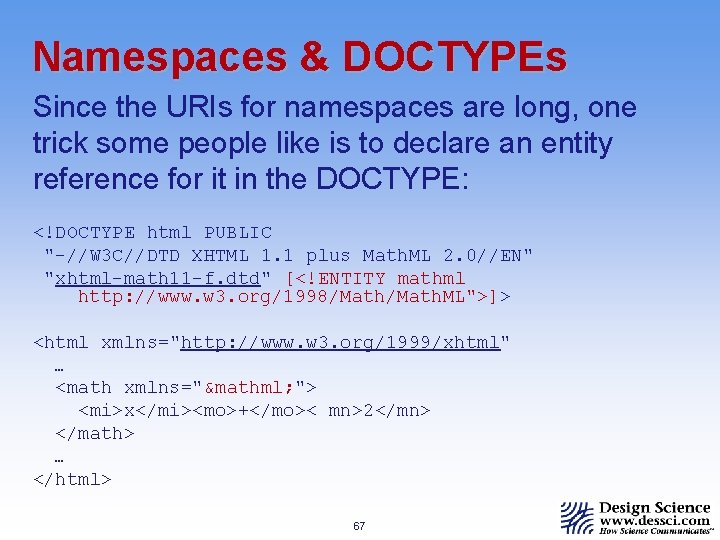

Namespaces & DOCTYPEs Since the URIs for namespaces are long, one trick some people like is to declare an entity reference for it in the DOCTYPE: <!DOCTYPE html PUBLIC "-//W 3 C//DTD XHTML 1. 1 plus Math. ML 2. 0//EN" "xhtml-math 11 -f. dtd" [<!ENTITY mathml http: //www. w 3. org/1998/Math. ML">]> <html xmlns="http: //www. w 3. org/1999/xhtml" … <math xmlns="&mathml; "> <mi>x</mi><mo>+</mo>< mn>2</mn> </math> … </html> 67

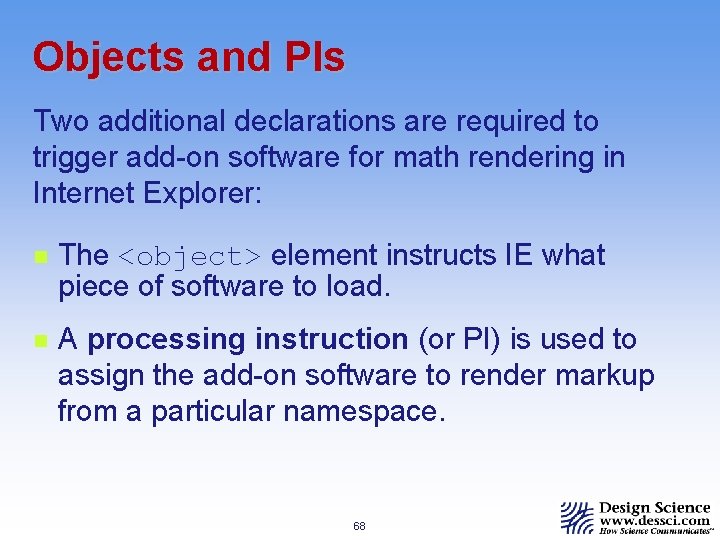

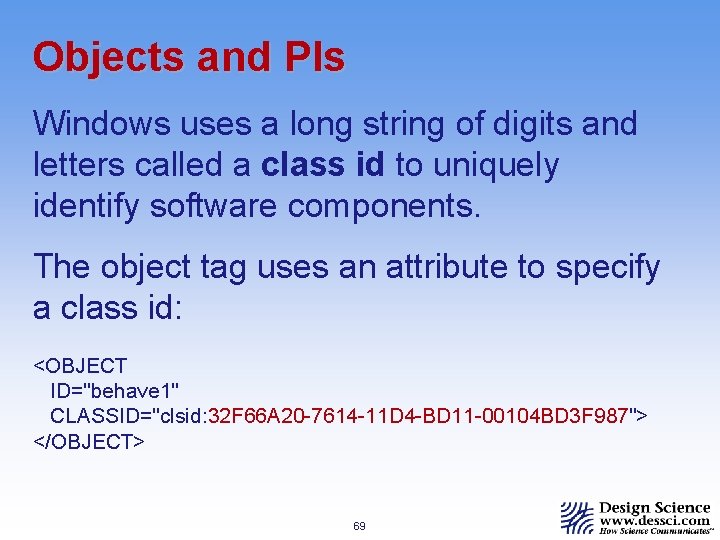

Objects and PIs Two additional declarations are required to trigger add-on software for math rendering in Internet Explorer: n The <object> element instructs IE what piece of software to load. n A processing instruction (or PI) is used to assign the add-on software to render markup from a particular namespace. 68

Objects and PIs Windows uses a long string of digits and letters called a class id to uniquely identify software components. The object tag uses an attribute to specify a class id: <OBJECT ID="behave 1" CLASSID="clsid: 32 F 66 A 20 -7614 -11 D 4 -BD 11 -00104 BD 3 F 987"> </OBJECT> 69

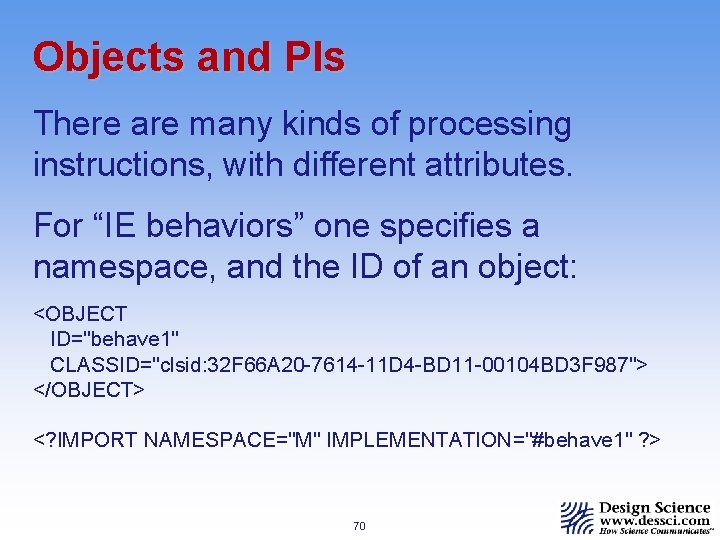

Objects and PIs There are many kinds of processing instructions, with different attributes. For “IE behaviors” one specifies a namespace, and the ID of an object: <OBJECT ID="behave 1" CLASSID="clsid: 32 F 66 A 20 -7614 -11 D 4 -BD 11 -00104 BD 3 F 987"> </OBJECT> <? IMPORT NAMESPACE="M" IMPLEMENTATION="#behave 1" ? > 70

Objects and PIs One complexity arises from a bug in Internet Explorer behaviors: n n Behaviors are actually triggered by a namespace prefix, and not the namespace itself. The upshot is, to use add-ons such as Math. Player or Techexplorer, n n You must include an OBJECT and PI. You must use the prefix method for namespaces. 71

Putting It Together Altogether then, to create a document that works in both IE and Netscape, you must: n n n Write XHTML Include a DOCTYPE Include an OBJECT and PI Include a namespace declaration Use namespace prefixes on the Math. ML 72

Putting It Together But wait! Even if you do all that, there is still the insurmountable problem of MIME types: n Netscape will only render your document if it is XML. n Internet Explorer will only render it if it is HTML. n The solution? XSL stylesheets… 73

The Math. ML Stylesheet An XSL stylesheet is a set of templates for transforming an input document into an output document. n You add an XSL stylesheet to an XML document using a PI. n The stylesheet sits on the server with your document. n The stylesheet runs in the client to transform your document for viewing. 74

The Math. ML Stylesheet XSL is powerful. The W 3 C Math WG has created a Universal Math. ML Stylesheet which can: n Detect what browser it is running in and output either XML or HTML accordingly n Detect what add-ons are installed and output the necessary Object and PI declarations n Convert content to presentation markup 75

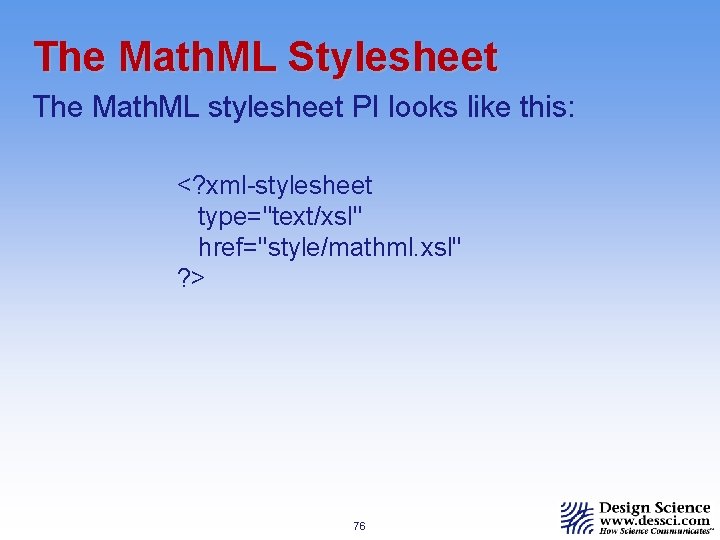

The Math. ML Stylesheet The Math. ML stylesheet PI looks like this: <? xml-stylesheet type="text/xsl" href="style/mathml. xsl" ? > 76

The Math. ML Stylesheet In order to use the Math. ML stylesheet, n n n Include the stylesheet PI. Write XHTML. Don’t use entity references. Use numeric references instead. Use namespaces to indicate the Math. ML. Don’t use Object tags or behavior PIs. It’s not necessary to use a DOCTYPE. 77

Summary Getting Math. ML in a document to render in both IE and Netscape is quite a trick. The necessary ingredients are: n n n The document must be XHTML (NS). It needs a DOCTYPE (NS). The Math. ML must be in a namespace (both, ) and you have to use the prefix method (IE). You need an <object> element and behavior PI (IE). Serve it as XML for NS, and HTML for IE. 78

Summary A simpler, alternative method which also deals with the MIME types is to use the Universal Math Stylesheet: n n The document must be XHTML without entity names. Include the stylesheet PI. The Math. ML must be in a namespace (either method). You can omit the DOCTYPE, <object> element and behavior PI. 79

- Slides: 79