Introduction to The Atom Theory PRESENTED BY 1

Introduction to The Atom Theory PRESENTED BY: 1. ANA ALINA 2. FIRDIANA SANJAYA

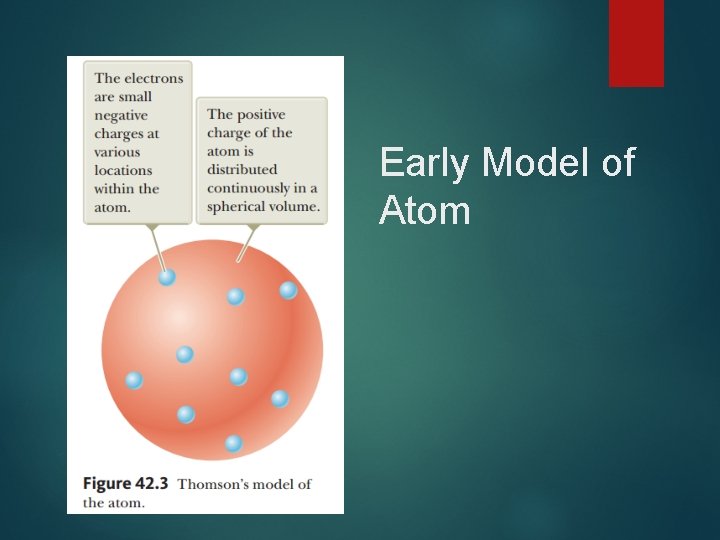

Early Model of Atom In 1897, J. J. Thomson suggested a model that describes the atom as a region in which positive charge is spread out in space with electrons embedded throughout the region, much like the seeds in a watermelon or raisins in thick pudding. he atom as a whole would then be electrically neutral.

Early Model of Atom

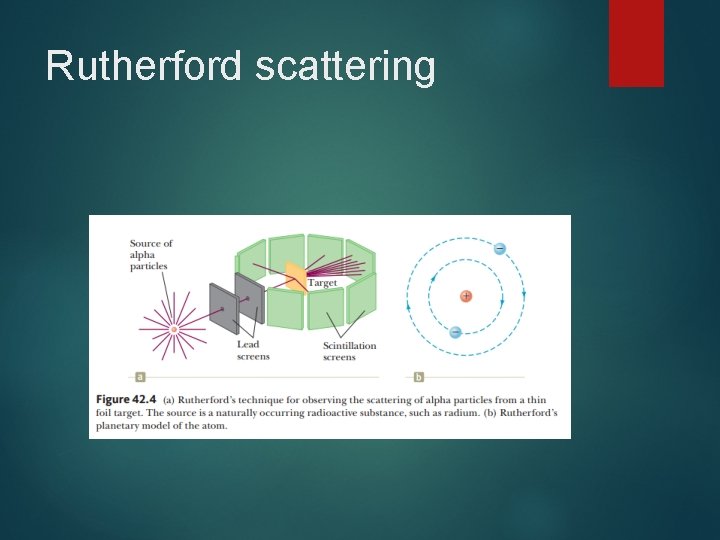

Rutherford scattering In 1911, Ernest Rutherford did an experiment that showed that Thomson’s model could not be correct. In this experiment, a beam of positively charged alpha particles (helium nuclei) was projected into a thin metallic foil such as the target.

Rutherford scattering Many of the particles deflected from their original direction of travel were scattered through large angles. Some particles were even deflected backward, completely reversing their direction of travel.

Rutherford scattering

Rutherford scattering Two basic difficulties exist with Rutherford’s planetary model : 1. an atom emits (and absorbs) certain characteristic frequencies of electromagnetic radiation and no others, but the Rutherford model cannot explain this phenomenon.

Rutherford scattering 2. A second difficulty is that Rutherford’s electrons are undergoing a centripetal acceleleration. According to Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism, centripetally accelerated charges revolving with frequency f should radiate electromagnetic waves of frequency f.

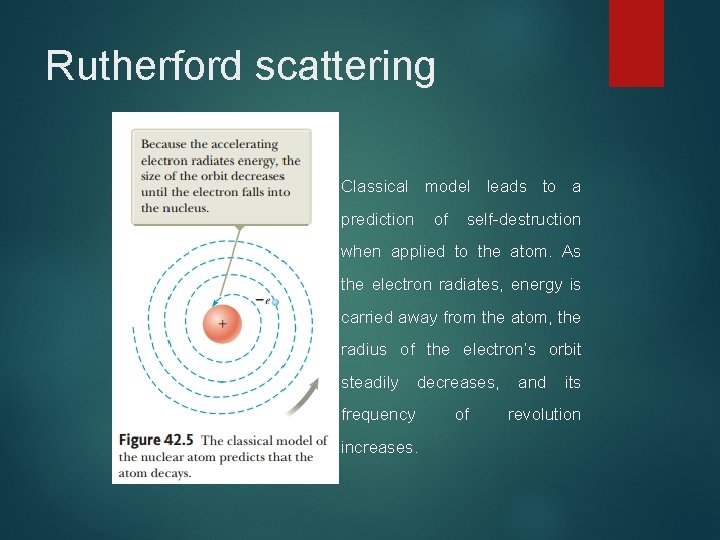

Rutherford scattering Classical model leads to a prediction of self-destruction when applied to the atom. As the electron radiates, energy is carried away from the atom, the radius of the electron’s orbit steadily decreases, frequency increases. of and its revolution

The Bohr Model Niels Bohr in 1913 when he presented a new model of the hydrogen atom that circumvented the difficulties of Rutherford’s planetary model.

The Bohr Model The postulates of the Bohr theory as it applies to the hydrogen atom are as follows : 1. the electron in orbit around the nucleus in the same way we treat a planet in orbit around a star.

The Bohr Model 2. the electron does not emit energy in the form of radiation, even though it is accelerating. 3. The atom emits radiation when the electron makes a transition from a more energetic initial stationary state to a lower-energy stationary state.

The Bohr Model 4. The size of an allowed electron orbit is determined by a condition imposed on the electron’s orbital angular momentum: We can analyze the energy very simply using concepts of circular motion and the potential energy associated with two charges. The electron has a charge of -e, while the nucleus has a charge of +Ze, where Z is the atomic number of the element.

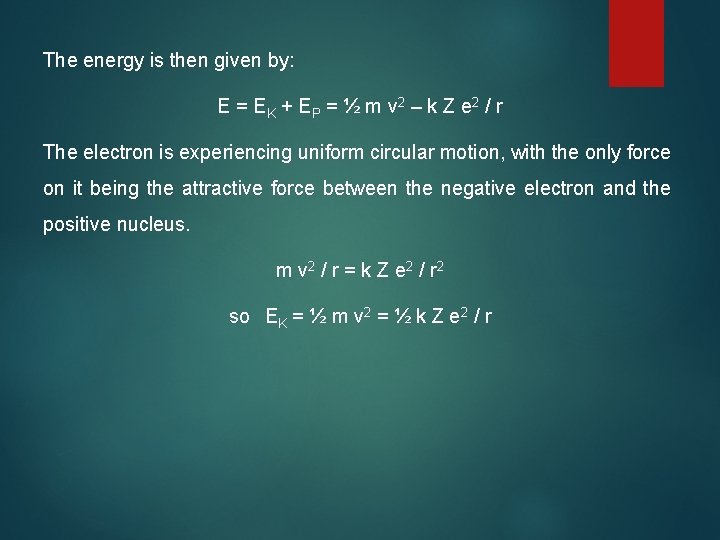

The energy is then given by: E = EK + EP = ½ m v 2 – k Z e 2 / r The electron is experiencing uniform circular motion, with the only force on it being the attractive force between the negative electron and the positive nucleus. m v 2 / r = k Z e 2 / r 2 so EK = ½ m v 2 = ½ k Z e 2 / r

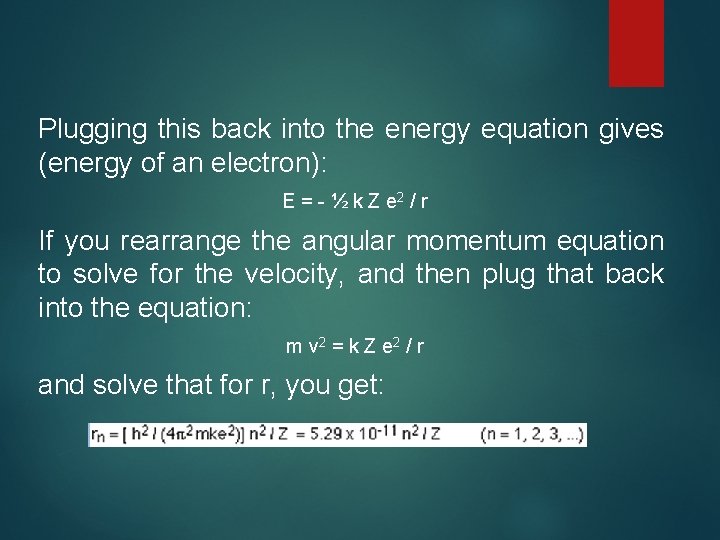

Plugging this back into the energy equation gives (energy of an electron): E = - ½ k Z e 2 / r If you rearrange the angular momentum equation to solve for the velocity, and then plug that back into the equation: m v 2 = k Z e 2 / r and solve that for r, you get:

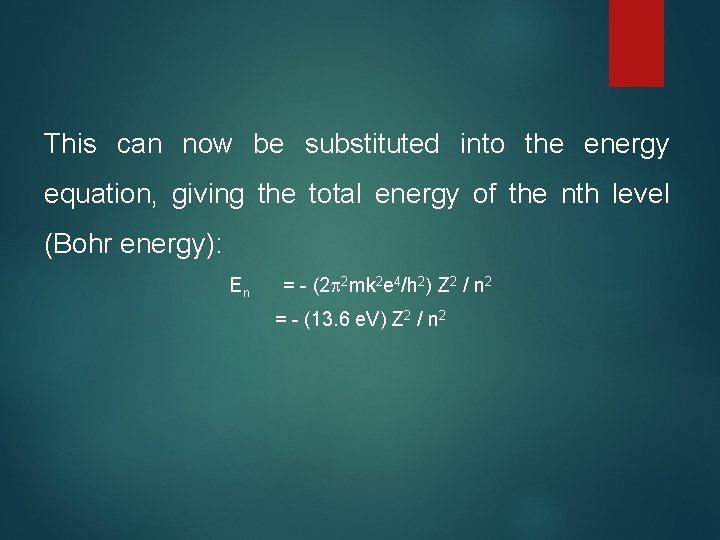

This can now be substituted into the energy equation, giving the total energy of the nth level (Bohr energy): En = - (2 2 mk 2 e 4/h 2) Z 2 / n 2 = - (13. 6 e. V) Z 2 / n 2

Energy Level Diagrams and The Hydrogen Atom Hydrogen has only one electron to worry abaut. The n=1 state is known as the groun state, while higher n states are known as excited states.

To conserve energy, a photon with an energy equal to the energy between the states will be emitted by the atom. In the hydrogen atom, energy of emitted photon can be found : E=hf

- Slides: 18