Introduction to Surgical Trials Sources of bias and

Introduction to Surgical Trials: Sources of bias and solutions Professor David Torgerson Director York Trials Unit Dept Health Sciences University of York David. Torgerson@york. ac. uk BOA Orthopaedic Surgery Research Centre

RCTs in Surgery • Surgery is a complex intervention • RCTs in surgery/complex interventions are more challenging than ‘standard’ drug trials – there are more potential sources of bias. • In this talk I will consider potential sources of bias that affect all trials and those that affect surgical or complex intervention studies.

Randomised Controlled Trials • In theory randomisation eliminates 3 sources of bias: – Selection bias – Regression to the mean – Temporal changes • As well as providing a secure foundation for statistical inference.

Randomisation works • When all participants have been allocated in a secure randomised fashion • All randomised participants have been followed up in their allocated groups • A single analysis at the end of the study with all participants is undertaken • All groups are treated the same (apart from the intervention) • Outcome assessment is independent and unbiased

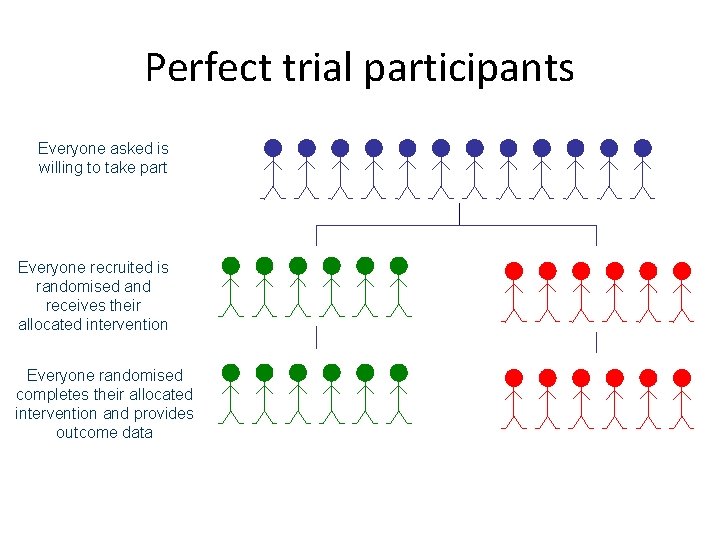

Perfect trial participants Everyone asked is willing to take part Everyone recruited is randomised and receives their allocated intervention Everyone randomised completes their allocated intervention and provides outcome data

Randomisation • Ensures that the two or more groups of patients are similar in both known and unknown characteristics that might affect outcome • BUT it does not ensure that there is a balance in surgical skill between the two groups (more on this later)

Subversion Bias • Subversion Bias occurs when a researcher or clinician manipulates participant recruitment such that groups formed at baseline are NOT equivalent. • Anecdotal, or qualitative evidence (I. e gossip), suggest that this is a widespread phenomenon. • Statistically this has been demonstrated as having occurred widely.

Subversion - qualitative evidence • Schulz has described, anecdotally, a number of incidents of researchers subverting allocation by looking at sealed envelopes through x-ray lights. • Researchers have confessed to breaking open filing cabinets to obtain the randomisation code. Schulz JAMA 1995; 274: 1456.

Quantitative Evidence • Trials with adequate concealed allocation show different effect sizes, which would not happen if allocation wasn’t being subverted. • Trials using simple randomisation are too equivalent for it to have occurred by chance.

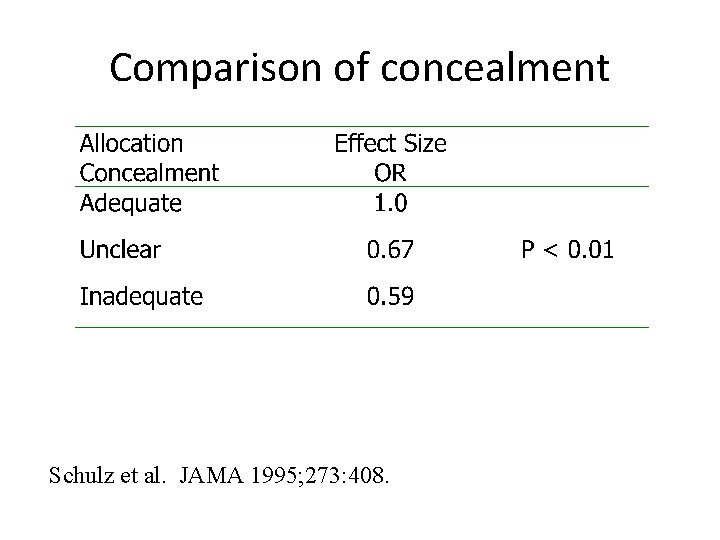

Poor concealment • Schulz et al. Examined 250 RCTs and classified them into having adequate concealment (where subversion was difficult), unclear, or inadequate where subversion was able to take place. • They found that badly concealed allocation led to increased effect sizes – showing CHEATING by researchers.

Comparison of concealment Schulz et al. JAMA 1995; 273: 408.

Small VS Large Trials • Small trials tend to give greater effect sizes than large trials, this shouldn’t happen. • Kjaergard et al, showed it was due to poor allocation concealment in small trials, when trials are grouped by allocation methods ‘secure’ allocation reduced effect by 51%. Kjaegard et al. Ann Intern Med 2001; 135: 982.

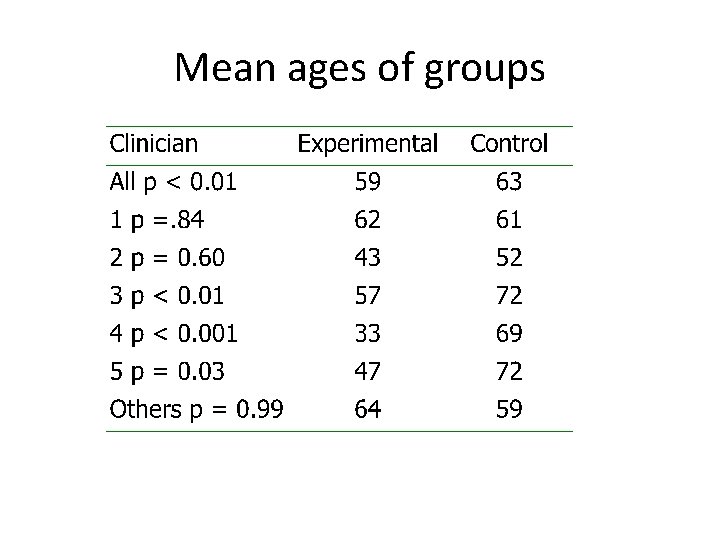

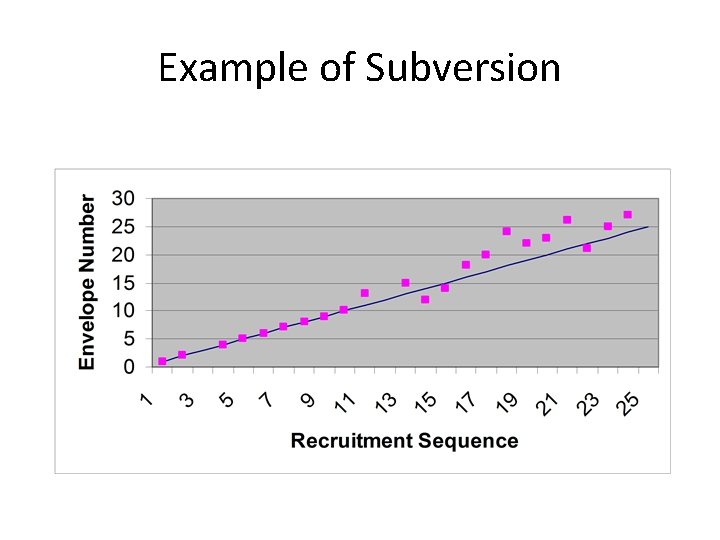

Case study • In a large surgical trial 5 centres were recruiting patients • Each centre had a box of sealed, opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes (which is generally thought of as being secure) • In each envelope was the surgical allocation (open or laparoscopic)

Mean ages of groups

Example of Subversion

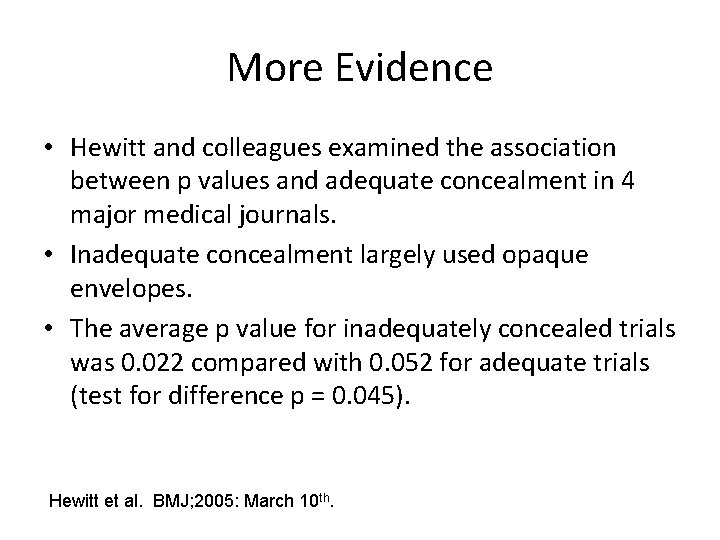

More Evidence • Hewitt and colleagues examined the association between p values and adequate concealment in 4 major medical journals. • Inadequate concealment largely used opaque envelopes. • The average p value for inadequately concealed trials was 0. 022 compared with 0. 052 for adequate trials (test for difference p = 0. 045). Hewitt et al. BMJ; 2005: March 10 th.

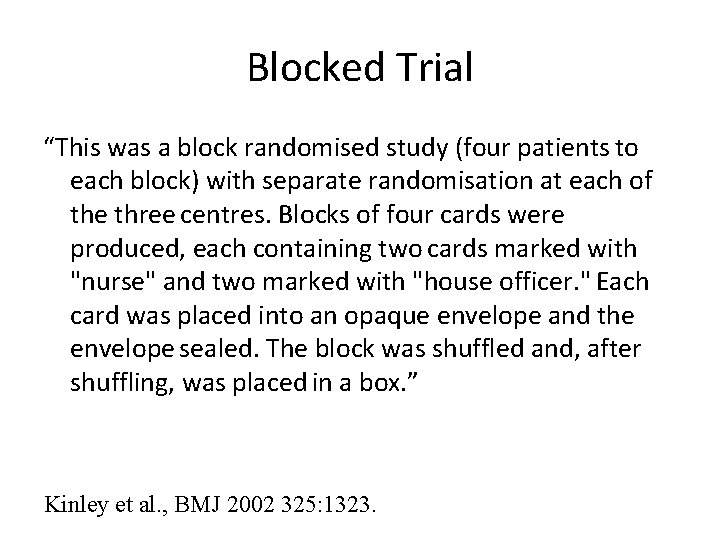

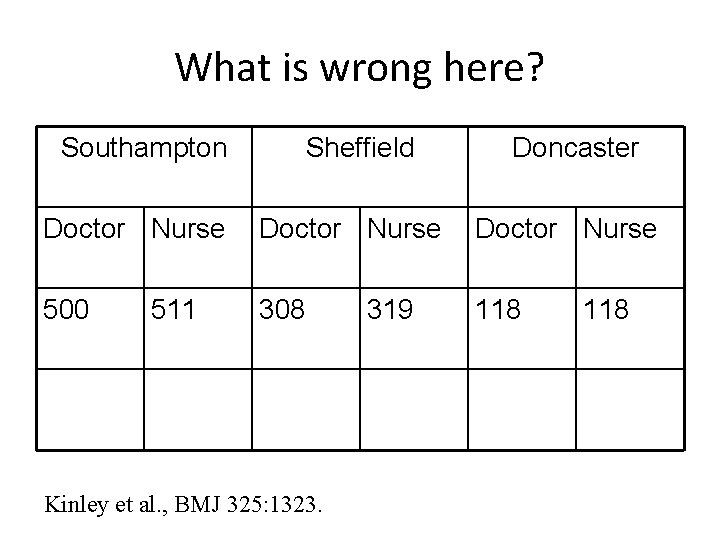

Blocked Trial “This was a block randomised study (four patients to each block) with separate randomisation at each of the three centres. Blocks of four cards were produced, each containing two cards marked with "nurse" and two marked with "house officer. " Each card was placed into an opaque envelope and the envelope sealed. The block was shuffled and, after shuffling, was placed in a box. ” Kinley et al. , BMJ 2002 325: 1323.

What is wrong here? Southampton Sheffield Doncaster Doctor Nurse 500 308 118 511 Kinley et al. , BMJ 325: 1323. 319 118

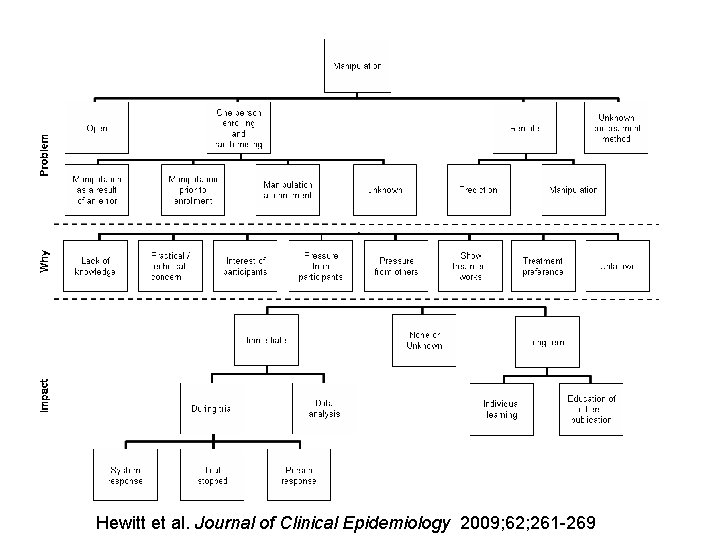

Hewitt et al. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2009; 62; 261 -269

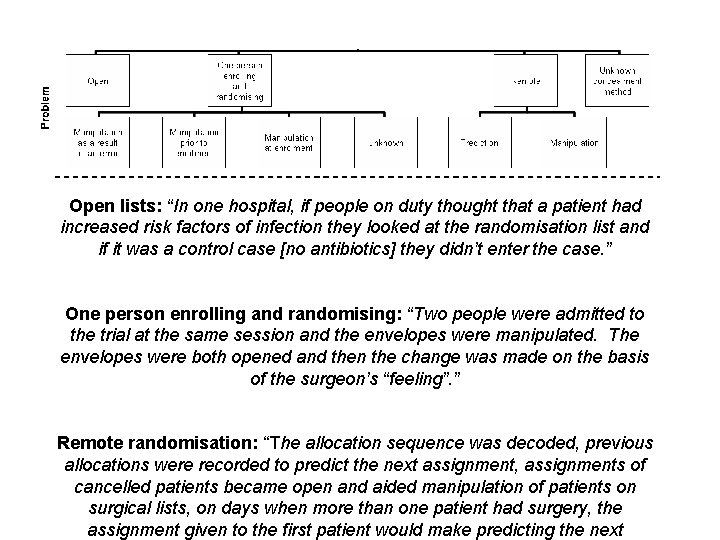

Open lists: “In one hospital, if people on duty thought that a patient had increased risk factors of infection they looked at the randomisation list and if it was a control case [no antibiotics] they didn’t enter the case. ” One person enrolling and randomising: “Two people were admitted to the trial at the same session and the envelopes were manipulated. The envelopes were both opened and then the change was made on the basis of the surgeon’s “feeling”. ” Remote randomisation: “The allocation sequence was decoded, previous allocations were recorded to predict the next assignment, assignments of cancelled patients became open and aided manipulation of patients on surgical lists, on days when more than one patient had surgery, the assignment given to the first patient would make predicting the next

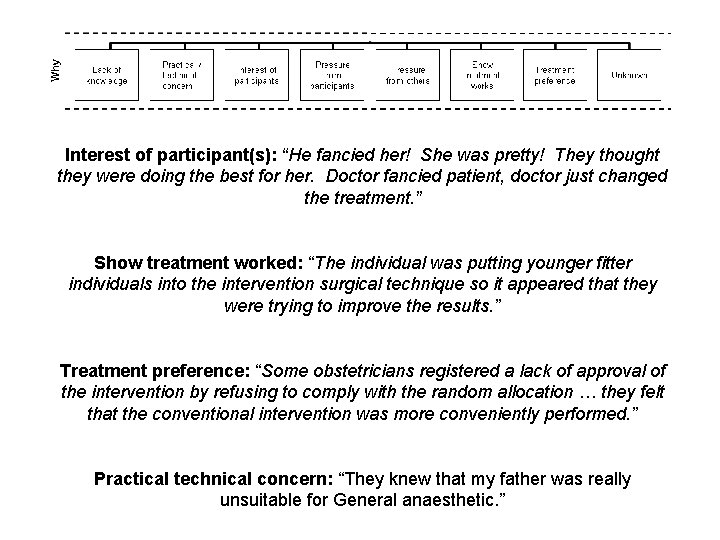

Interest of participant(s): “He fancied her! She was pretty! They thought they were doing the best for her. Doctor fancied patient, doctor just changed the treatment. ” Show treatment worked: “The individual was putting younger fitter individuals into the intervention surgical technique so it appeared that they were trying to improve the results. ” Treatment preference: “Some obstetricians registered a lack of approval of the intervention by refusing to comply with the random allocation … they felt that the conventional intervention was more conveniently performed. ” Practical technical concern: “They knew that my father was really unsuitable for General anaesthetic. ”

Subversion - summary • Appears to be widespread • Secure allocation usually prevents this form of bias • Need not be too expensive • Essential to prevent cheating • Envelopes not a secure method of allocation concealment – need to use telephone or web based methods.

Attrition, non-compliance, bias • Usually most trials lose participants after randomisation. This can cause bias, particularly if attrition differs between groups. • If a treatment has side-effects this may make drop outs higher among the less well participants, which can make a treatment appear to be effective when it is not. • Also usually some patients when allocated to a treatment change their minds and refuse the treatment or the controls access the treatment.

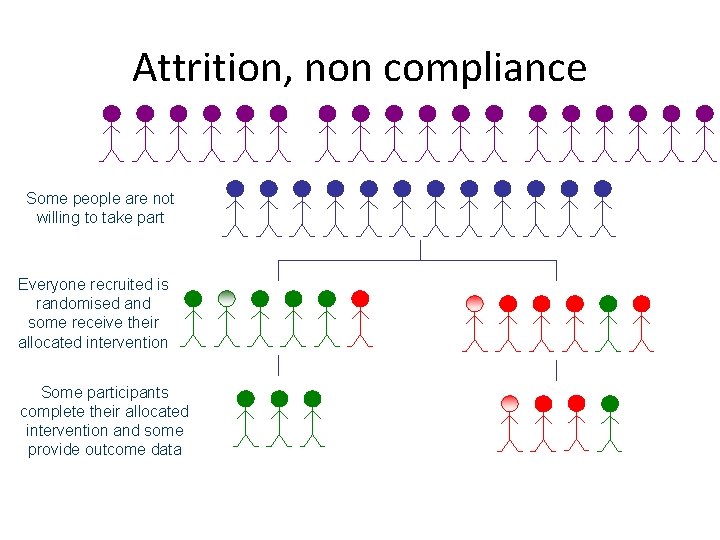

Attrition, non compliance Some people are not willing to take part Everyone recruited is randomised and some receive their allocated intervention Some participants complete their allocated intervention and some provide outcome data

Attrition – selection bias? • Attrition in the form of complete loss to follow -up can reintroduce selection bias that randomisation has dealt with • If the lost participants are a non-random sample, which differs between groups, then it is possible selection bias is introduced • Ideally small attrition similar between groups and baseline characteristics of ANALYSED groups are similar

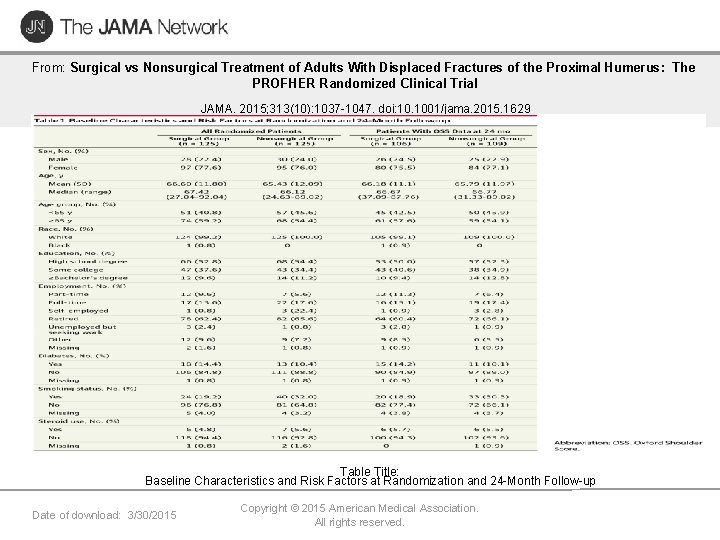

From: Surgical vs Nonsurgical Treatment of Adults With Displaced Fractures of the Proximal Humerus: The PROFHER Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA. 2015; 313(10): 1037 -1047. doi: 10. 1001/jama. 2015. 1629 Table Title: Baseline Characteristics and Risk Factors at Randomization and 24 -Month Follow-up Date of download: 3/30/2015 Copyright © 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Treatment crossover • Some randomised participants crossover from one group to another • To preserve randomisation we need to use Intention To Treat (ITT) analysis – all are analysed as they are randomised • If you do not use ITT then you are likely to introduce selection bias • ITT will result in a dilution of effect, but can be dealt with by CACE analysis

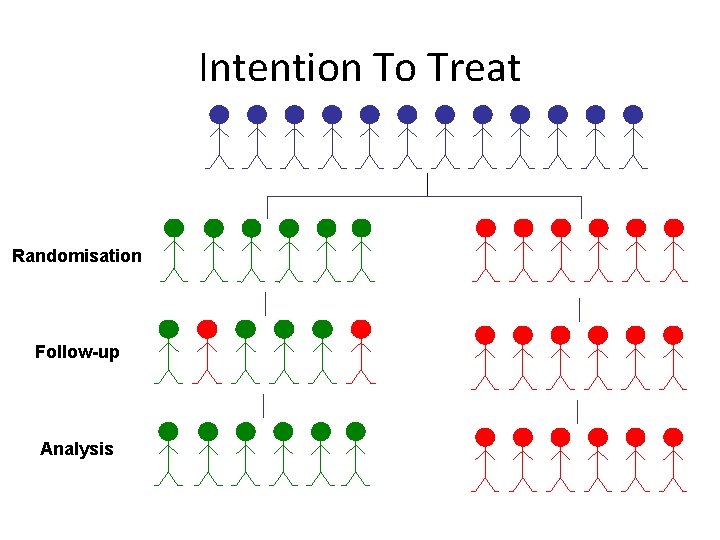

Intention To Treat Randomisation Follow-up Analysis

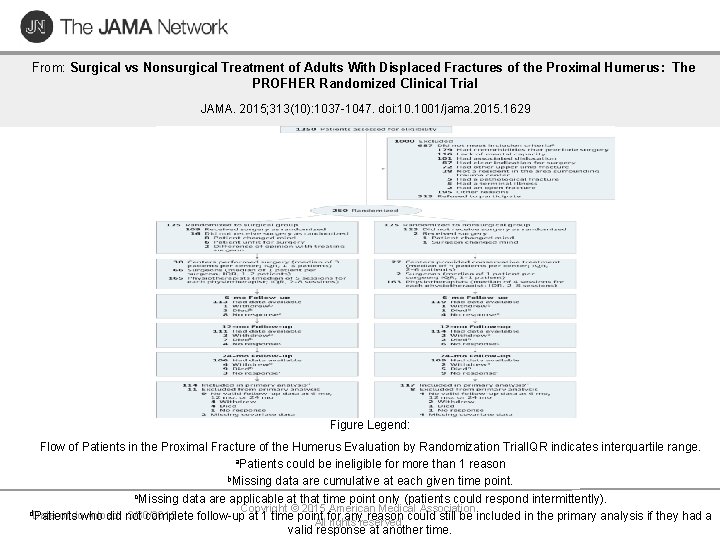

From: Surgical vs Nonsurgical Treatment of Adults With Displaced Fractures of the Proximal Humerus: The PROFHER Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA. 2015; 313(10): 1037 -1047. doi: 10. 1001/jama. 2015. 1629 Figure Legend: Flow of Patients in the Proximal Fracture of the Humerus Evaluation by Randomization Trial. IQR indicates interquartile range. a. Patients could be ineligible for more than 1 reason b. Missing data are cumulative at each given time point. c. Missing data are applicable at that time point only (patients could respond intermittently). Copyright © 2015 American Medical Association. d. Date of download: 3/30/2015 Patients who did not complete follow-up at 1 time point for any reason could still be included in the primary analysis if they had a All rights reserved. valid response at another time.

Popular but incorrect • Many/most RCTs where there is the presence of non-compliance undertake a ‘per protocol’ or an ‘on treatment analysis’ • This is wrong as it introduces selection bias • A better approach to estimate on treatment effects is to use CACE

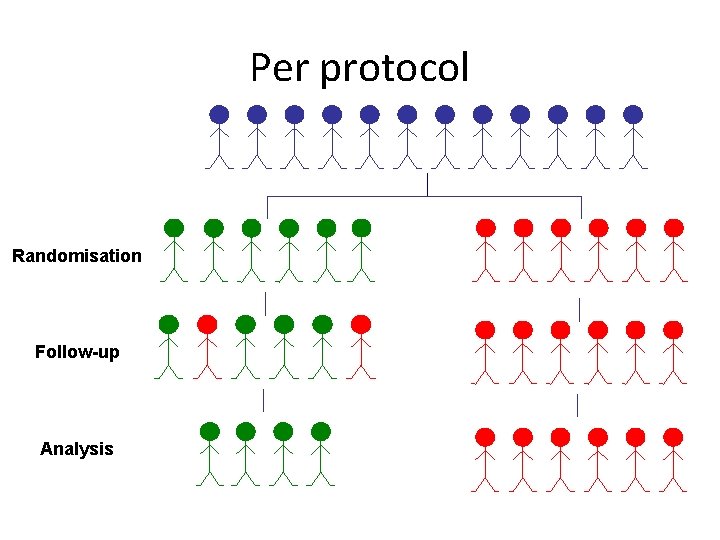

Per protocol Randomisation Follow-up Analysis

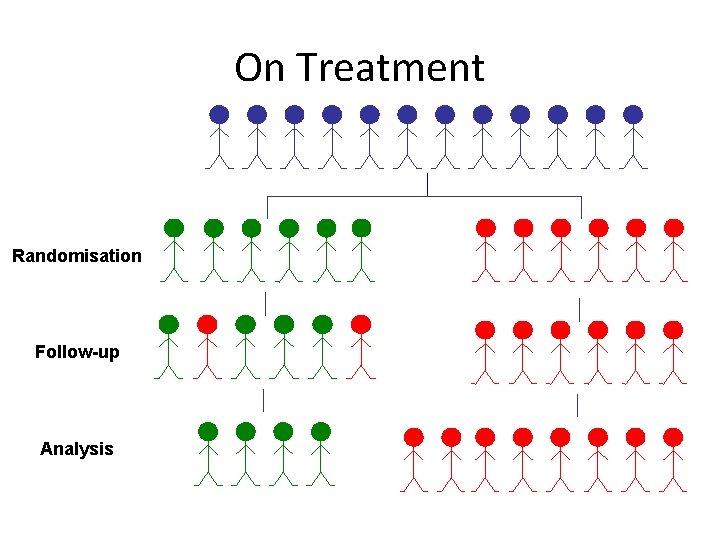

On Treatment Randomisation Follow-up Analysis

Attrition, compliance – summary • Several types of attrition • Treatment Refusers allocated treatment but complies with follow-up – solution Intention To Treat, CACE analysis • Partial Trial Refusers to fill in some outcome measures – partial solution complete primary outcome and or get data from other sources (e. g. , GP) • Completely withdraws – problem, analysis may use data imputation, but not complete solution

A single analysis at study end • Most trials are designed and powered on a single analysis at the end of the study • Most trials however are plagued by subgroup and secondary analyses • The success or failure of an intervention should rest on a single pre-determined outcome at the study end.

Sub-Group analysis: example. • In a large RCT of asprin for myocardial infarction a sub-group analysis showed that people with the star signs Gemini and Libra aspirin was INEFFECTIVE. • This is complete NONSENSE! • This shows dangers of subgroup analyses. Lancet 1988; ii: 349 -60.

Groups receive equivalent treatment • Apart from the intervention both groups should be treated the same: – Similar length of clinical appointments (unless intervention requires different length and numbers) – Similar follow up schedule by same people (don’t have surgeons assess intervention and practice nurses assess controls) – Similar length of q’naires etc

Outcome assessment • Ideally should be blind (not always possible if it is a patient quality of life outcome) • Example, of homeopathy study of histamine, showed an effect when researchers were not blind to the allocation but no effect when they were • Assessment of MS patients showed a difference when clinical staff were not blind, no difference when they were Noseworthy et al. (1994) The impact of blinding on the results of a randomized, placebo- controlled multiple sclerosis clinical trial. Neurology 44, 16 -20.

Problems with surgical trials • Patients usually know what treatment they will get – possible resentful demoralisation • Patients are randomised – surgeons usually are not • Surgeon effects • Learning curves

Resentful Demoralisation • This can occur when participants are randomised to treatment they do not want. • This may lead to them reporting outcomes badly in ‘revenge’ • This can lead to bias • One solution is to ask for preferences at baseline and adjust for these in the analysis

Learning Curves • Most new surgical techniques require some ‘learning’ consequently outcomes for patients early on not as good as later • Evaluating a new against an established technique may underestimate the effectiveness of the novel approach

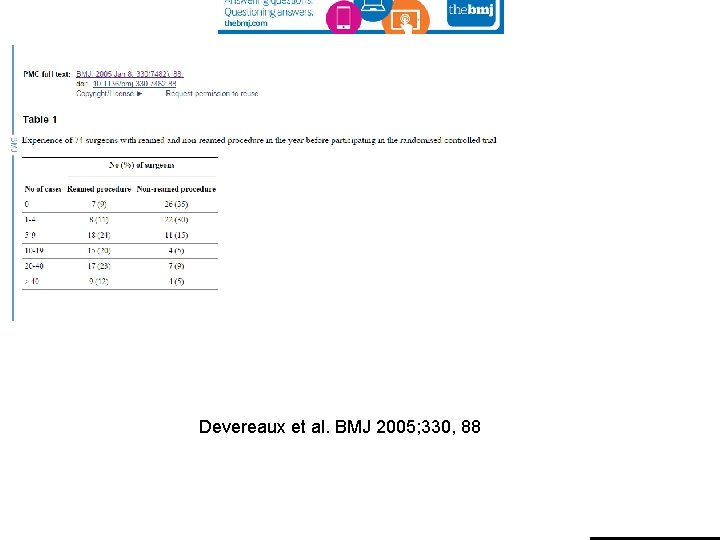

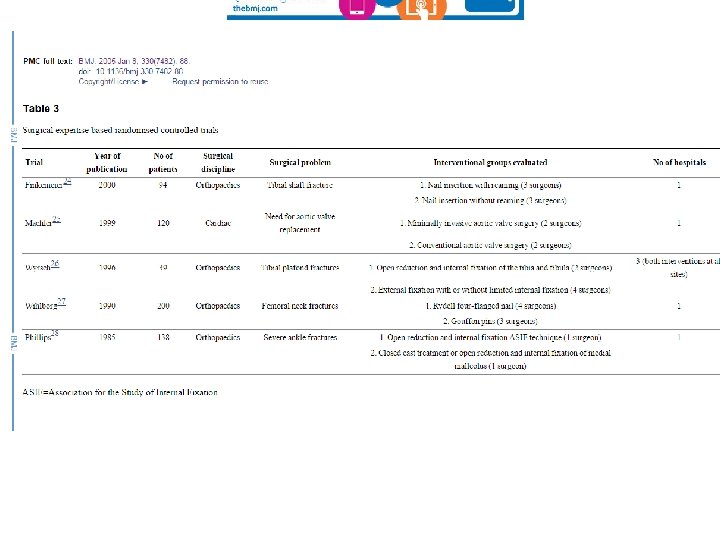

Devereaux et al. BMJ 2005; 330, 88

Solutions? • Recruit only surgeons with similar expertise in both techniques – Difficult to do; increases challenge of recruitment • Only evaluate established procedures – Exposed many patients to inferior sugery • Randomise anyway (unequal? ) and statistically adjust for learning curve – Need large trials and stats methods not widely used • Expertise based trials – More later!

Patients randomised not surgeons • Randomisation of patients ensures selection bias is eliminated on patient characteristics • BUT surgeons may have selected themselves to offer different surgical treatments – Treatment A might attract good surgeons; Treatment B might attract duff ones – so if Treatment A is better is it because the surgery or the surgeon is better?

Possible solutions 1 • Only select surgeons who can do both operations and they treat both groups of patients • Potential problem: – Although surgeons treating both sets of patients surgeons may prefer or be better at one type of surgery than the other (especially the older form of surgery) or unconsciously perform badly for ‘unprefered procedure’ plus problems with learning curve

Possible solutions - 2 • Recruit surgeons who could do both and randomise them to be trained and then deliver only one of the two types of surgery. May avoid preference problem? • Potential problems: – Similar to previous solution • Both solutions will not capitalise on surgeon preference

Possible solution 3: Expertise based trial • Patients randomised to surgeons who are experts in both treatments. This will be pragmatic as patients will typically be seen by a specialist. Surgeon should treat as best he/she can. Protects against learning curve effects. – Disadvantage – still a selection effect problem that may never be resolved – results may not apply to usual care surgeons being retrained

Surgeon Effect • A RCT of an intervention delivered by a single surgeon is hopeless as the treatment effects are perfectly confounded by the surgeon • To achieve generalisability we need multiple surgeons who are representative of the surgical community

Additional issues • Surgery vs non-surgical treatments have a statistical issue of clustering in the surgical arm around the surgeon and no clustering in the non-surgical arm • Until recently this was ignored but statistical methods are now being used to deal with this

Summary • Surgical trials face many of the same difficulties as ‘normal’ trials • Careful design can avoid many pitfalls • Involve methodologists at an early stage of the trial design

References • • • Devereaux et al. Need for expertise based randomised controlled trials BMJ 2005; 330, 88 Hewitt et al. Adequacy and reporting of allocation concealment: review of recent trials published in four general medical journals BMJ 2005; 330: 1057 -8. Hewitt C, Torgerson DJ. Restricted Randomisation: Is it necessary? BMJ 206; 332, 1506 -1508. ISIS-2 Collaborative Group. Randomised trial of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither among 17 187 cases of suspected acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 1988 ii, 349 -360. Kjaergaard LL, Villumsen J, Cluud C. Reported Methodologic Quality and discrepancies between large and small randomized trials in meta-analyses. Ann Intern Med 2001 135, 982 -989 Noseworthy J, Ebers GC, Vandervoot MK, Farquhar RE, Yetisir E, Roberts R. (1994) The impact of blinding on the results of a randomized, placebo- controlled multiple sclerosis clinical trial. Neurology 44, 16 -20. Ramsey et al. Assessment of the learning curve in health technologies: a systematic review In J Technol Assess Health Care 2000; 16: 1095 -1108. Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias: dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 1995; 273, 408 -412. Torgerson and Torgerson 2008, Designing randomised trials in health, education and the social sciences, Palgrave Mac. Millan

- Slides: 52