Introduction to Statistics and probability theory Nature of

Introduction to Statistics and probability theory Nature of data, design of experiments, sample space, events, complement,

Random Experiments We are all familiar with the importance of experiments in science and engineering. 2

Random Experiments Experimentation is useful to us because we can assume that if we perform certain experiments under very nearly identical conditions, we will arrive at results that are essentially the same. In these circumstances, we are able to control the value of the variables that affect the outcome of the experiment. However, in some experiments, we are not able to ascertain or control the value of certain variables so that the results will vary from one performance of the experiment to the next, even though most of the conditions are the same. These experiments are described as random. Example If we toss a die, the result of the experiment is that it will come up with one of the numbers in the set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. 3

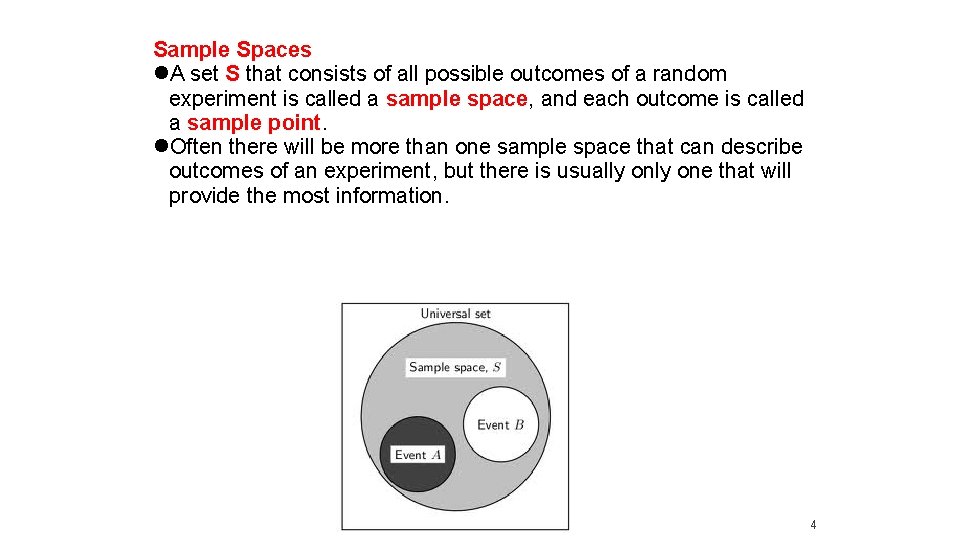

Sample Spaces A set S that consists of all possible outcomes of a random experiment is called a sample space, and each outcome is called a sample point. Often there will be more than one sample space that can describe outcomes of an experiment, but there is usually one that will provide the most information. 4

Example If we toss a die, then one sample space is given by {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} while another is {even, odd}. It is clear, however, that the latter would not be adequate to determine, for example, whether an outcome is divisible by 3. If is often useful to portray a sample space graphically. In such cases, it is desirable to use numbers in place of letters whenever possible. 5

If a sample space has a finite number of points, it is called a finite sample space. If it has as many points as there are natural numbers 1, 2, 3, …. , it is called a countably infinite sample space. If it has as many points as there are in some interval on the x axis, such as 0 ≤ x ≤ 1, it is called a noncountably infinite sample space. A sample space that is finite or countably finite is often called a discrete sample space, while one that is noncountably infinite is called a nondiscrete sample space. Example The sample space resulting from tossing a die yields a discrete sample space. However, picking any number, not just integers, from 1 to 10, yields a nondiscrete sample space. 6

Events An event is a subset A of the sample space S, i. e. , it is a set of possible outcomes. If the outcome of an experiment is an element of A, we say that the event A has occurred. An event consisting of a single point of S is called a simple or elementary event. As particular events, we have S itself, which is the sure or certain event since an element of S must occur, and the empty set ∅, which is called the impossible event because an element of ∅ cannot occur. 7

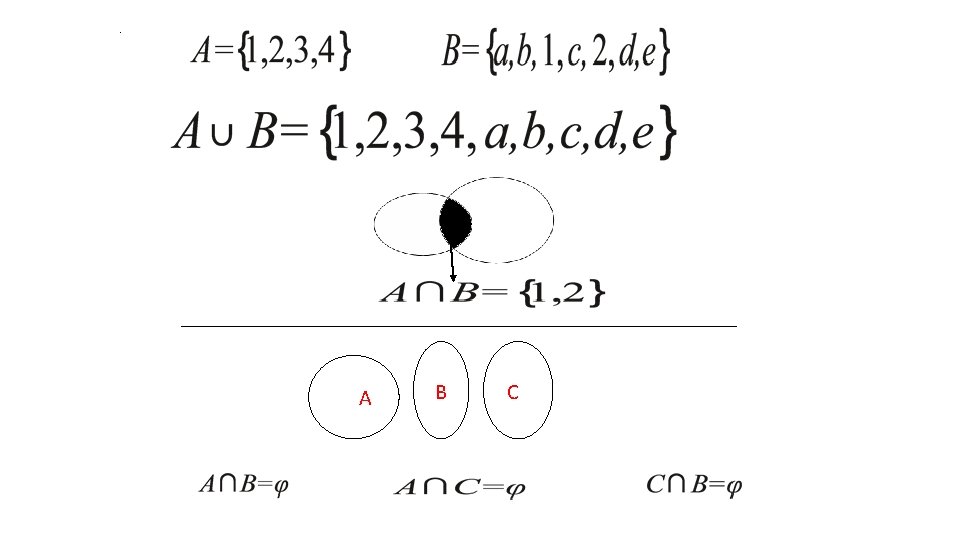

By using set operations on events in S, we can obtain other events in S. For example, if A and B are events, then A ∪ B is the event “either A or B or both. ” A ∪ B is called the union of A and B. A ∩ B is the event “both A and B. ” A ∩ B is called the intersection of A and B. A′ is the event “not A. ” A′ is called the complement of A. A – B = A ∩ B′ is the event “A but not B. ” In particular, A′ = S – A. 8

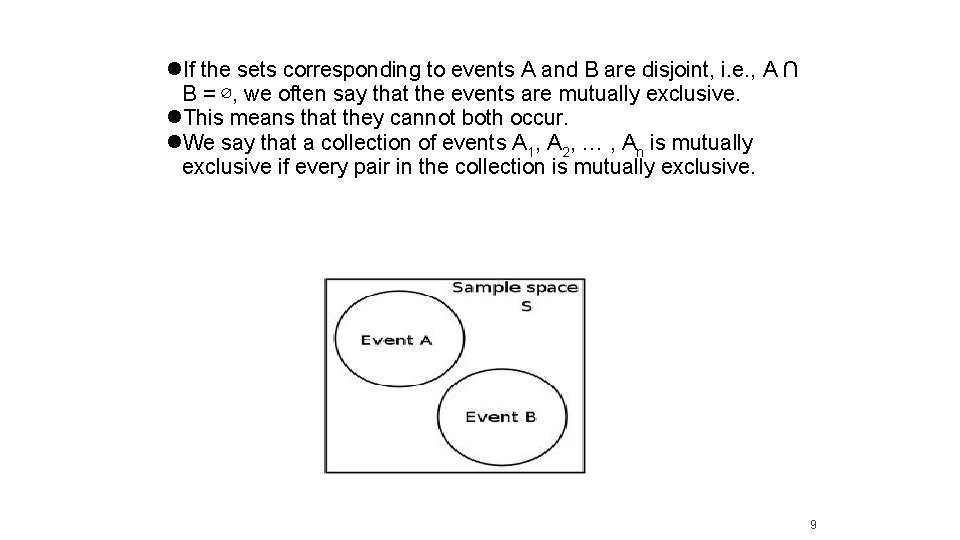

If the sets corresponding to events A and B are disjoint, i. e. , A ∩ B = ∅, we often say that the events are mutually exclusive. This means that they cannot both occur. We say that a collection of events A 1, A 2, … , An is mutually exclusive if every pair in the collection is mutually exclusive. 9

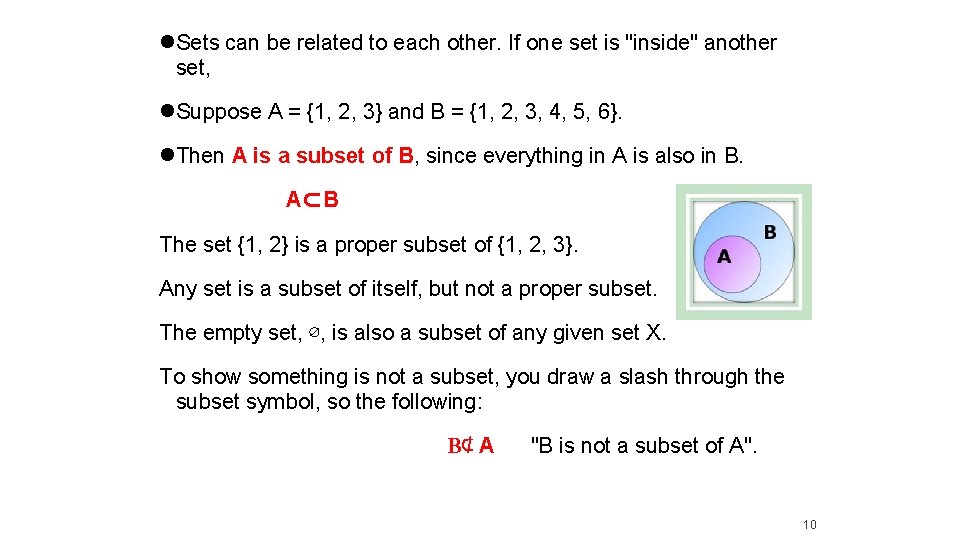

Sets can be related to each other. If one set is "inside" another set, Suppose A = {1, 2, 3} and B = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}. Then A is a subset of B, since everything in A is also in B. A⊂B The set {1, 2} is a proper subset of {1, 2, 3}. Any set is a subset of itself, but not a proper subset. The empty set, ∅, is also a subset of any given set X. To show something is not a subset, you draw a slash through the subset symbol, so the following: B⊄ A "B is not a subset of A". 10

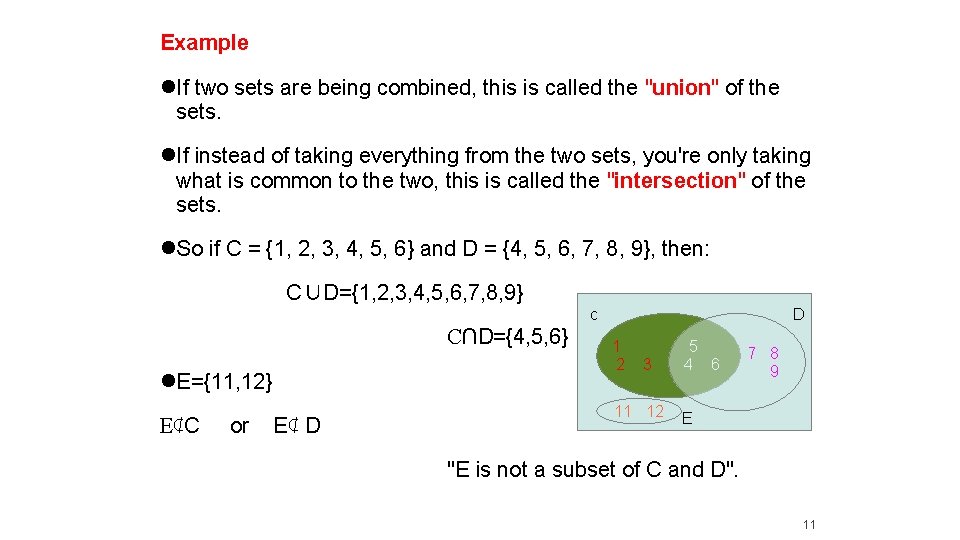

Example If two sets are being combined, this is called the "union" of the sets. If instead of taking everything from the two sets, you're only taking what is common to the two, this is called the "intersection" of the sets. So if C = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} and D = {4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9}, then: C∪D={1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9} c C∩D={4, 5, 6} E={11, 12} E⊄C or E⊄ D D 1 2 3 11 12 5 4 6 7 8 9 E "E is not a subset of C and D". 11

A∩B B A A B C C

Example o Give a solution using the roster method: A = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 }, B is a subset of A, the elements of B are even. The numbers in A that are even 2, 4, and 6, so B = {2, 4, 6}. o What is the intersection of A = { x is odd } and B = { x is between -4 and 6 }, where the elements of the two sets are integers? Since "intersection" means "only things that are in both sets", the intersection will be all the numbers which are both odd and between – 4 and 6. {– 3, – 1, 1, 3, 5} o What is the union of A = { x is a natural number between 4 and 8 inclusive } and B = { x is a single-digit negative integer }? Since "union" means "anything that is in either set", the union will be everything from A plus everything in B. Since A = { 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 } and B = { – 9, – 8, – 7, – 6, – 5, – 4, – 3, – 2, – 1 }, then their union is: { – 9, – 8, – 7, – 6, – 5, – 4, – 3, – 2, – 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 } 13

The Concept of Probability Many things in everyday life, from stock price to flash flood, are random phenomena for which the outcome is uncertain. The concept of probability provides us with the idea on how to measure the chances of possible outcomes. Probability enables us to quantify uncertainty, which is described in terms of mathematics. 14

The Concept of Probability In any random experiment there is always uncertainty as to whether a particular event will or will not occur. As a measure of the chance, or probability, with which we can expect the event to occur, it is convenient to assign a number between 0 and 1. If we are sure or certain that an event will occur, we say that its probability is 100% or 1. If we are sure that the event will not occur, we say that its probability is zero. If, for example, the probability is ¹⁄4 , we would say that there is a 25% chance it will occur and a 75% chance that it will not occur. Equivalently, we can say that the odds (probability) against occurrence are 75% to 25%, or 3 to 1. 15

There are two important procedures by means of which we can estimate the probability of an event. CLASSICAL APPROACH: If an event can occur in h different ways out of a total of n possible ways, all of which are equally likely, then the probability of the event is h/n. FREQUENCY APPROACH: If after n repetitions of an experiment, where n is very large, an event is observed to occur in h of these, then the probability of the event is h/n. This is also called the empirical probability of the event. Both the classical and frequency approaches have serious drawbacks, the first because the words “equally likely” are vague and the second because the “large number” involved is vague. Because of these difficulties, mathematicians have been led to an axiomatic approach to probability. 16

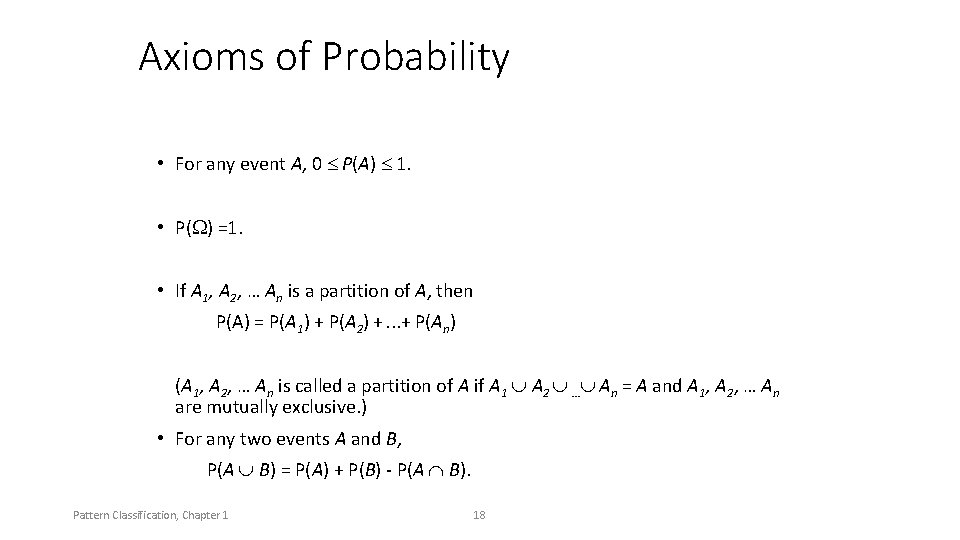

The Axioms of Probability Suppose we have a sample space S. If S is discrete, all subsets correspond to events and conversely; if S is nondiscrete, only special subsets (called measurable) correspond to events. To each event A in the class C of events, we associate a real number P(A). The P is called a probability function, and P(A) the probability of the event, if the following axioms are satisfied. 17

Axioms of Probability • For any event A, 0 P(A) 1. • P( ) =1. • If A 1, A 2, … An is a partition of A, then P(A) = P(A 1) + P(A 2) +. . . + P(An) (A 1, A 2, … An is called a partition of A if A 1 A 2 … An = A and A 1, A 2, … An are mutually exclusive. ) • For any two events A and B, P(A B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A B). Pattern Classification, Chapter 1 18

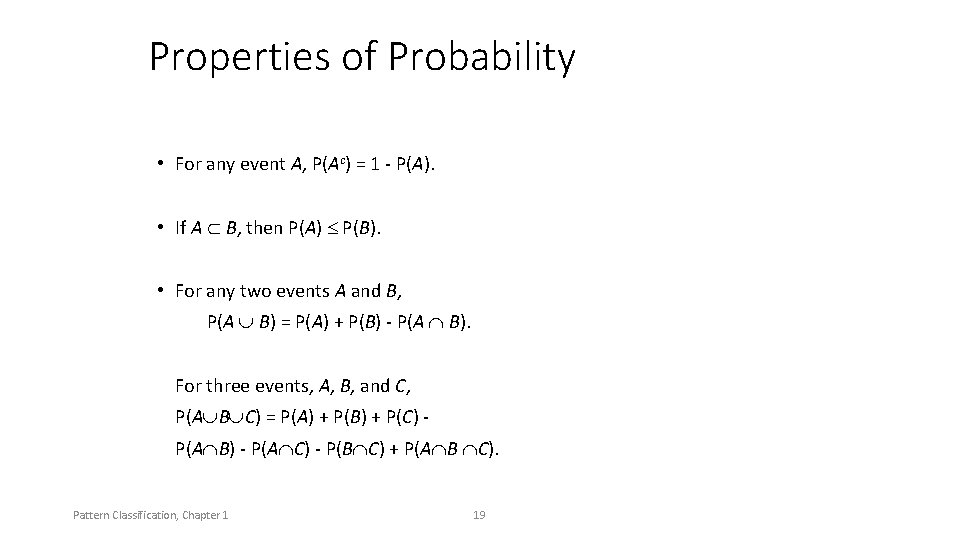

Properties of Probability • For any event A, P(Ac) = 1 - P(A). • If A B, then P(A) P(B). • For any two events A and B, P(A B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A B). For three events, A, B, and C, P(A B C) = P(A) + P(B) + P(C) P(A B) - P(A C) - P(B C) + P(A B C). Pattern Classification, Chapter 1 19

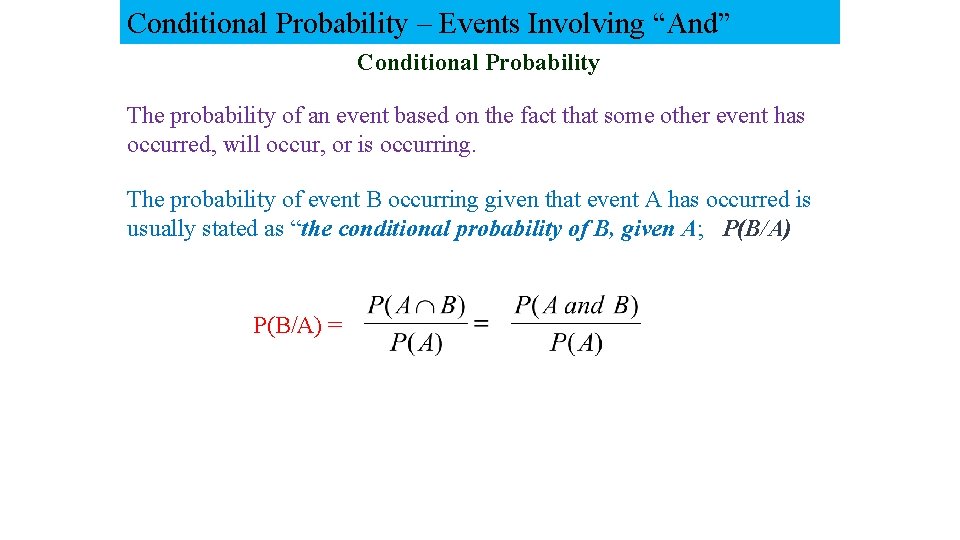

Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Conditional Probability The probability of an event based on the fact that some other event has occurred, will occur, or is occurring. The probability of event B occurring given that event A has occurred is usually stated as “the conditional probability of B, given A; P(B/A) =

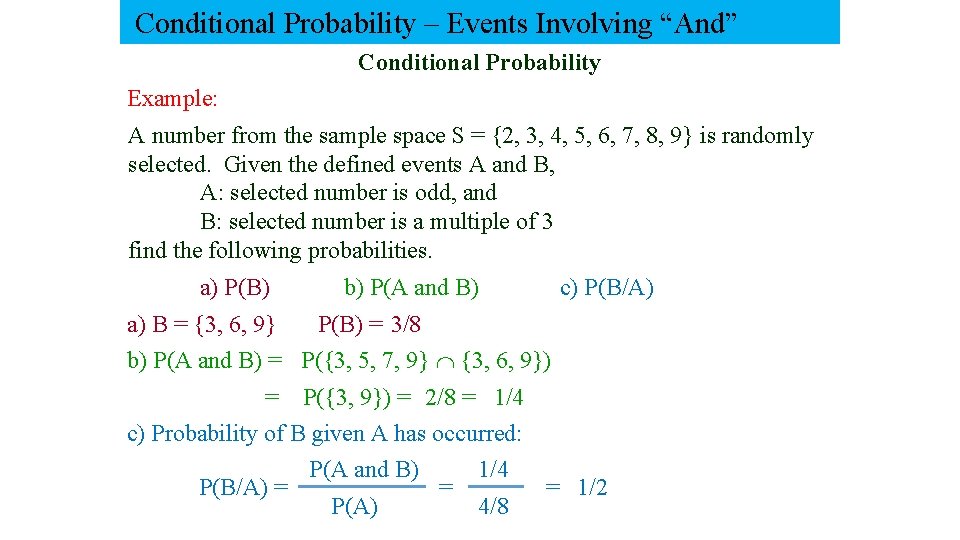

Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Conditional Probability Example: A number from the sample space S = {2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9} is randomly selected. Given the defined events A and B, A: selected number is odd, and B: selected number is a multiple of 3 find the following probabilities. a) P(B) a) B = {3, 6, 9} b) P(A and B) c) P(B/A) P(B) = 3/8 b) P(A and B) = P({3, 5, 7, 9} {3, 6, 9}) = P({3, 9}) = 2/8 = 1/4 c) Probability of B given A has occurred: P(B/A) = P(A and B) P(A) = 1/4 4/8 = 1/2

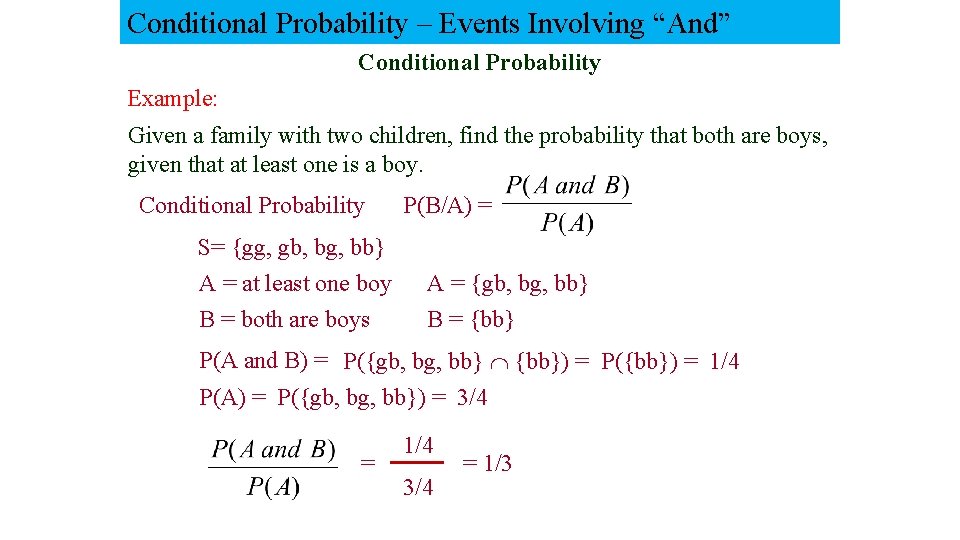

Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Conditional Probability Example: Given a family with two children, find the probability that both are boys, given that at least one is a boy. Conditional Probability P(B/A) = S= {gg, gb, bg, bb} A = at least one boy B = both are boys A = {gb, bg, bb} B = {bb} P(A and B) = P({gb, bg, bb} {bb}) = P({bb}) = 1/4 P(A) = P({gb, bg, bb}) = 3/4 = 1/4 3/4 = 1/3

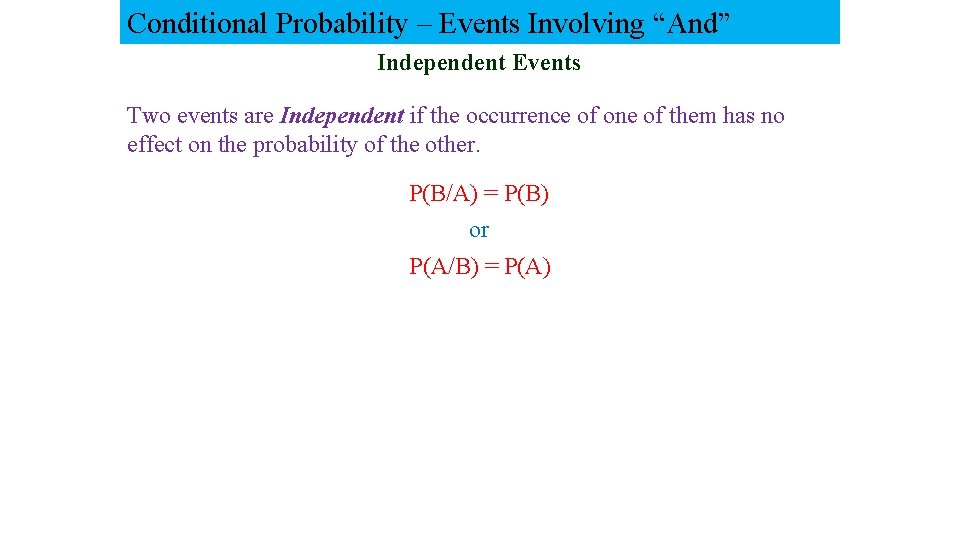

Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Independent Events Two events are Independent if the occurrence of one of them has no effect on the probability of the other. P(B/A) = P(B) or P(A/B) = P(A)

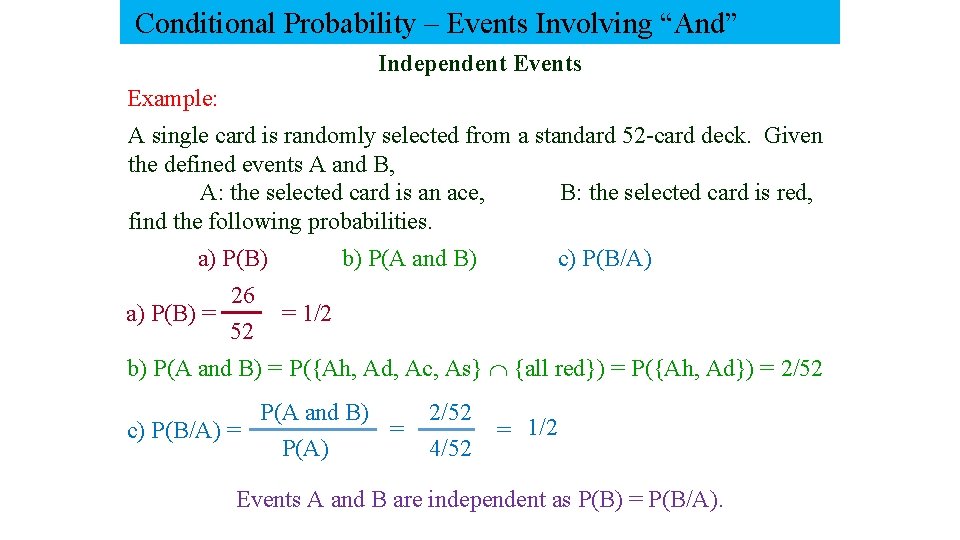

Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Independent Events Example: A single card is randomly selected from a standard 52 -card deck. Given the defined events A and B, A: the selected card is an ace, B: the selected card is red, find the following probabilities. a) P(B) = 26 52 b) P(A and B) c) P(B/A) = 1/2 b) P(A and B) = P({Ah, Ad, Ac, As} {all red}) = P({Ah, Ad}) = 2/52 c) P(B/A) = P(A and B) P(A) = 2/52 4/52 = 1/2 Events A and B are independent as P(B) = P(B/A).

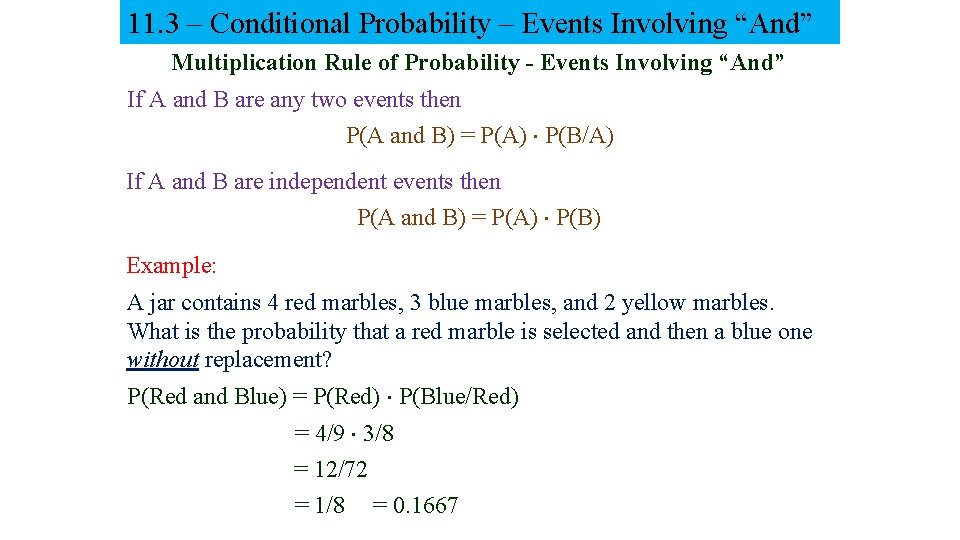

11. 3 – Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Multiplication Rule of Probability - Events Involving “And” If A and B are any two events then P(A and B) = P(A) P(B/A) If A and B are independent events then P(A and B) = P(A) P(B) Example: A jar contains 4 red marbles, 3 blue marbles, and 2 yellow marbles. What is the probability that a red marble is selected and then a blue one without replacement? P(Red and Blue) = P(Red) P(Blue/Red) = 4/9 3/8 = 12/72 = 1/8 = 0. 1667

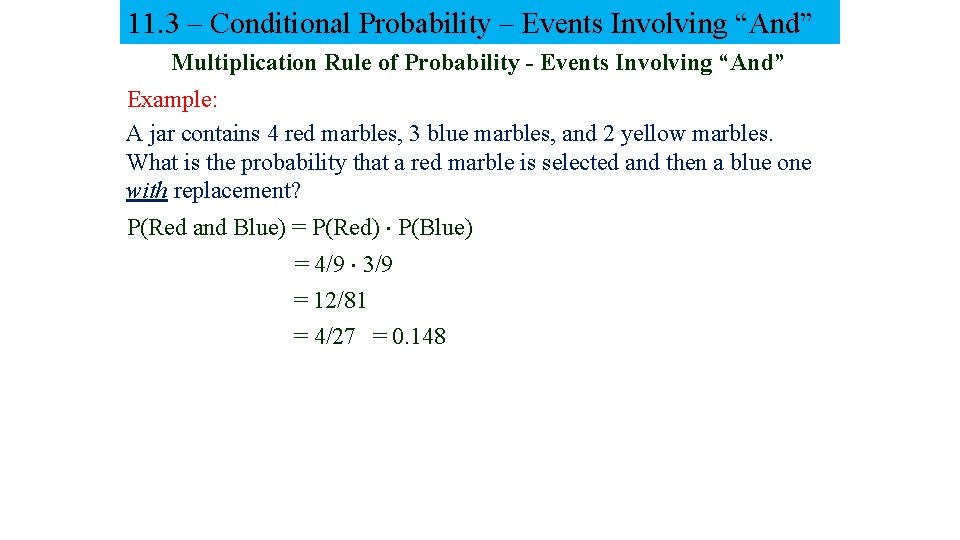

11. 3 – Conditional Probability – Events Involving “And” Multiplication Rule of Probability - Events Involving “And” Example: A jar contains 4 red marbles, 3 blue marbles, and 2 yellow marbles. What is the probability that a red marble is selected and then a blue one with replacement? P(Red and Blue) = P(Red) P(Blue) = 4/9 3/9 = 12/81 = 4/27 = 0. 148

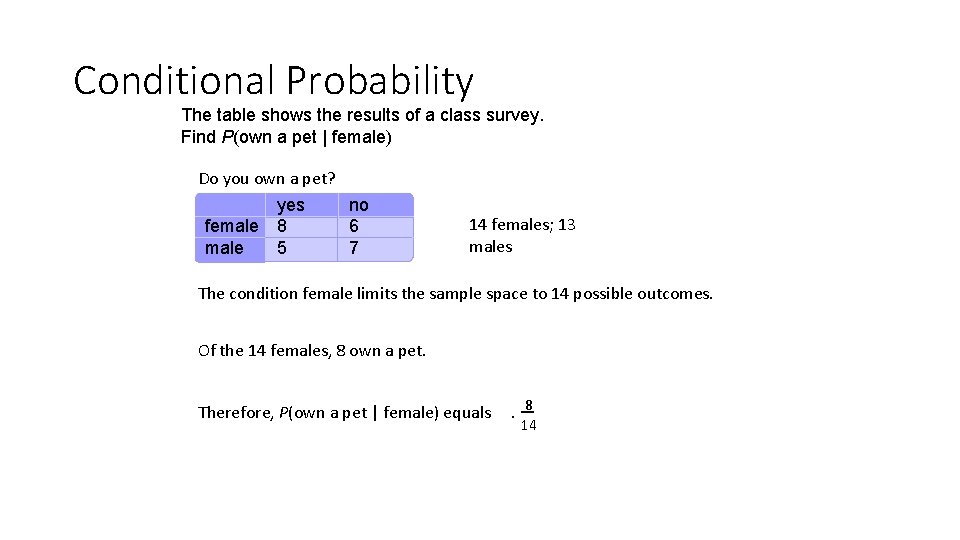

Conditional Probability The table shows the results of a class survey. Find P(own a pet | female) Do you own a pet? yes no female 8 6 male 5 7 14 females; 13 males The condition female limits the sample space to 14 possible outcomes. Of the 14 females, 8 own a pet. Therefore, P(own a pet | female) equals . 8 14

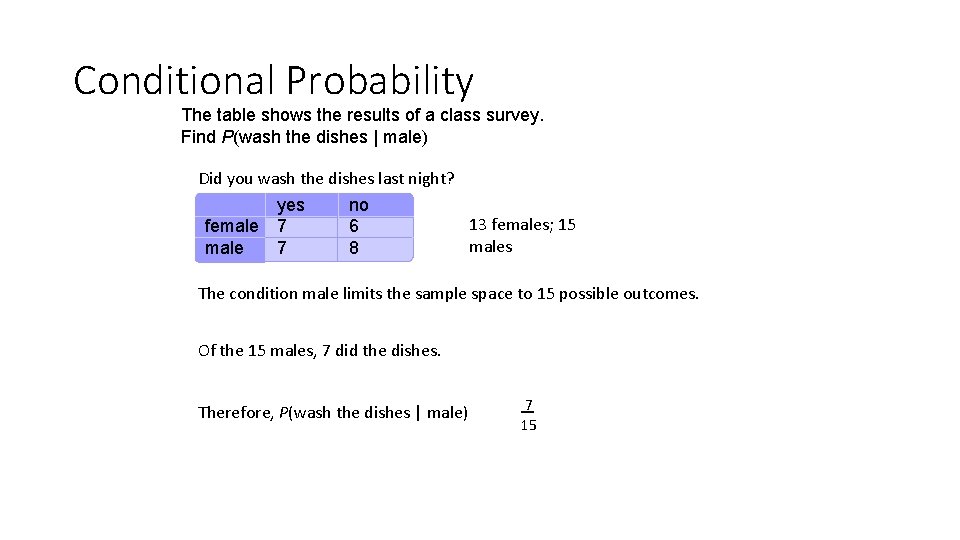

Conditional Probability The table shows the results of a class survey. Find P(wash the dishes | male) Did you wash the dishes last night? yes no 13 females; 15 female 7 6 males male 7 8 The condition male limits the sample space to 15 possible outcomes. Of the 15 males, 7 did the dishes. Therefore, P(wash the dishes | male) 7 15

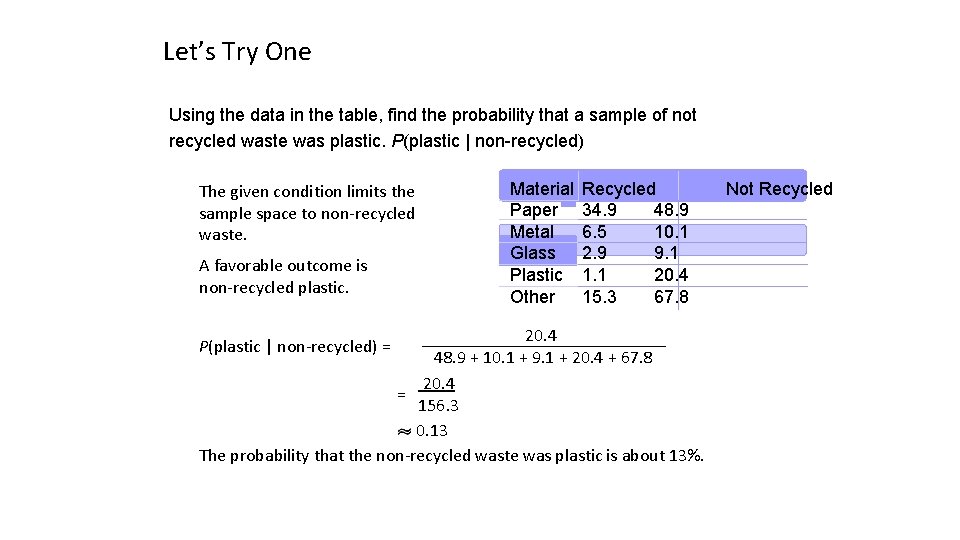

Let’s Try One Using the data in the table, find the probability that a sample of not recycled waste was plastic. P(plastic | non-recycled) The given condition limits the sample space to non-recycled waste. A favorable outcome is non-recycled plastic. Material Paper Metal Glass Plastic Other Recycled 34. 9 48. 9 6. 5 10. 1 2. 9 9. 1 1. 1 20. 4 15. 3 67. 8 20. 4 48. 9 + 10. 1 + 9. 1 + 20. 4 + 67. 8 20. 4 = 156. 3 0. 13 The probability that the non-recycled waste was plastic is about 13%. P(plastic | non-recycled) = Not Recycled

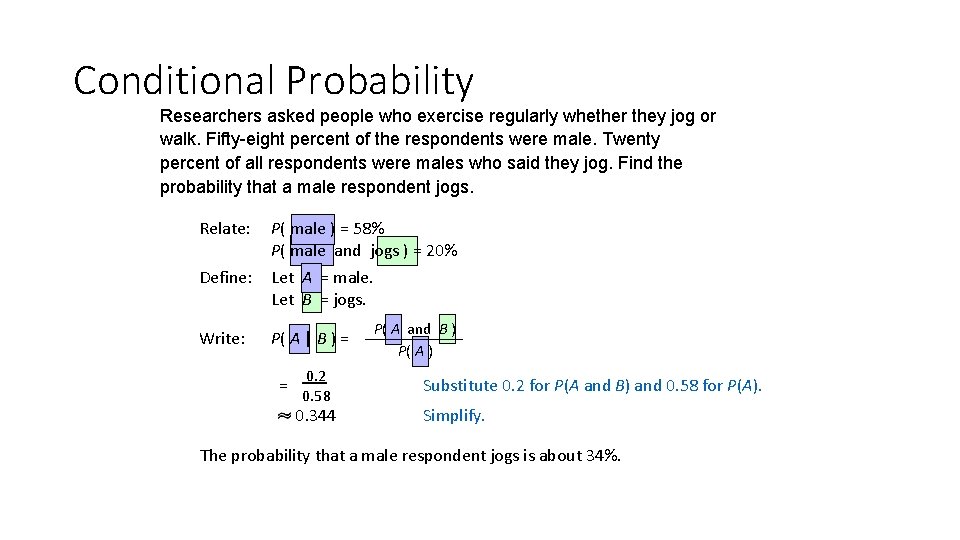

Conditional Probability Researchers asked people who exercise regularly whether they jog or walk. Fifty-eight percent of the respondents were male. Twenty percent of all respondents were males who said they jog. Find the probability that a male respondent jogs. Relate: P( male ) = 58% P( male and jogs ) = 20% Define: Let A = male. Let B = jogs. Write: P( A | B ) = = 0. 2 0. 58 0. 344 P( A and B ) P( A ) Substitute 0. 2 for P(A and B) and 0. 58 for P(A). Simplify. The probability that a male respondent jogs is about 34%.

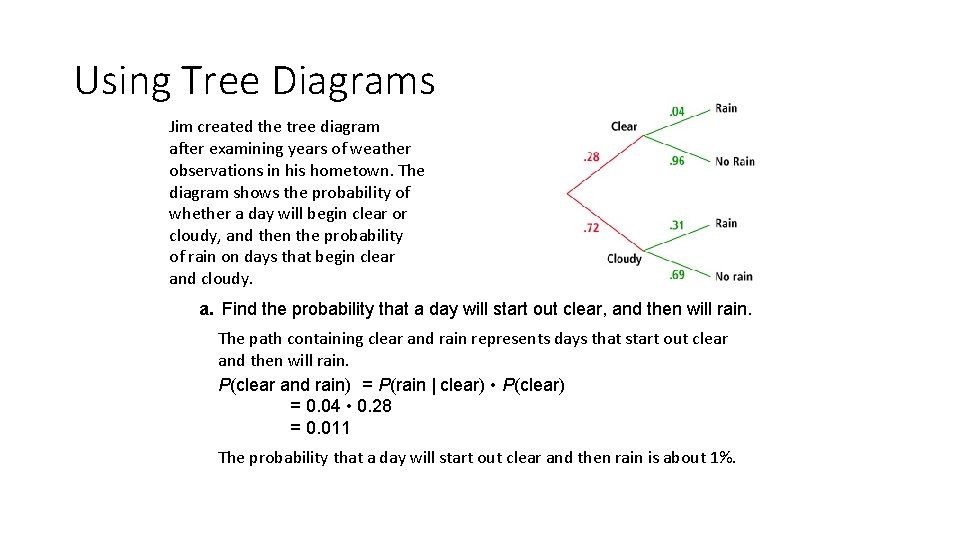

Using Tree Diagrams Jim created the tree diagram after examining years of weather observations in his hometown. The diagram shows the probability of whether a day will begin clear or cloudy, and then the probability of rain on days that begin clear and cloudy. a. Find the probability that a day will start out clear, and then will rain. The path containing clear and rain represents days that start out clear and then will rain. P(clear and rain) = P(rain | clear) • P(clear) = 0. 04 • 0. 28 = 0. 011 The probability that a day will start out clear and then rain is about 1%.

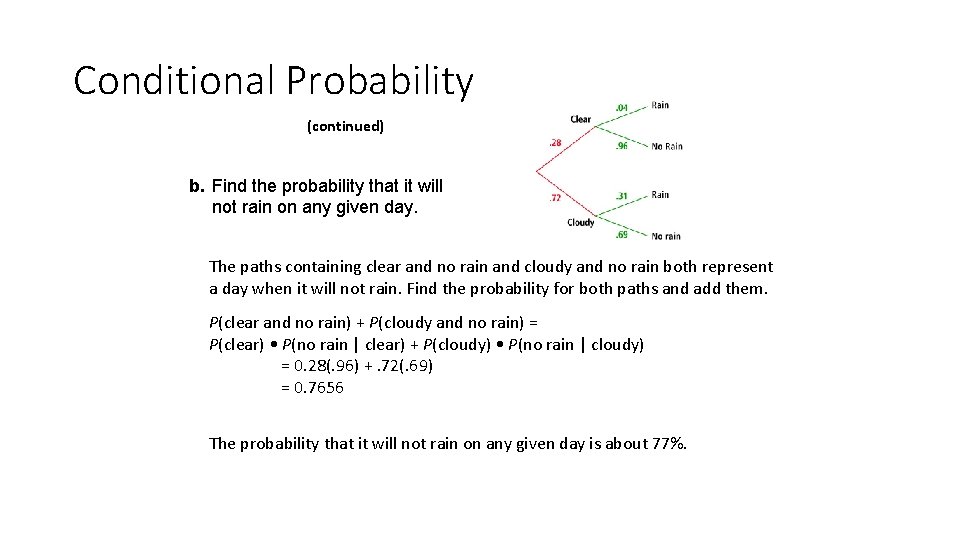

Conditional Probability (continued) b. Find the probability that it will not rain on any given day. The paths containing clear and no rain and cloudy and no rain both represent a day when it will not rain. Find the probability for both paths and add them. P(clear and no rain) + P(cloudy and no rain) = P(clear) • P(no rain | clear) + P(cloudy) • P(no rain | cloudy) = 0. 28(. 96) +. 72(. 69) = 0. 7656 The probability that it will not rain on any given day is about 77%.

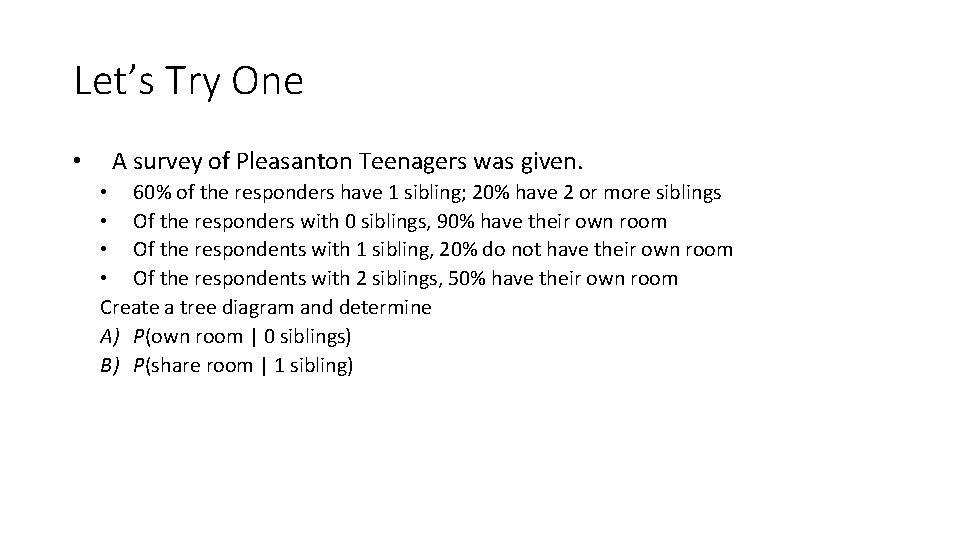

Let’s Try One • A survey of Pleasanton Teenagers was given. • 60% of the responders have 1 sibling; 20% have 2 or more siblings • Of the responders with 0 siblings, 90% have their own room • Of the respondents with 1 sibling, 20% do not have their own room • Of the respondents with 2 siblings, 50% have their own room Create a tree diagram and determine A) P(own room | 0 siblings) B) P(share room | 1 sibling)

• 60% of the responders have 1 sibling; 20% have 2 or more siblings • Of the responders with no siblings, 90% have their own room • Of the respondents with 1 sibling, 20% do not have their own room • Of the respondents with 2 siblings, 50% have their own room Create a tree diagram and determine A) P(own room | 0 siblings) B) P(share room | 1 sibling)

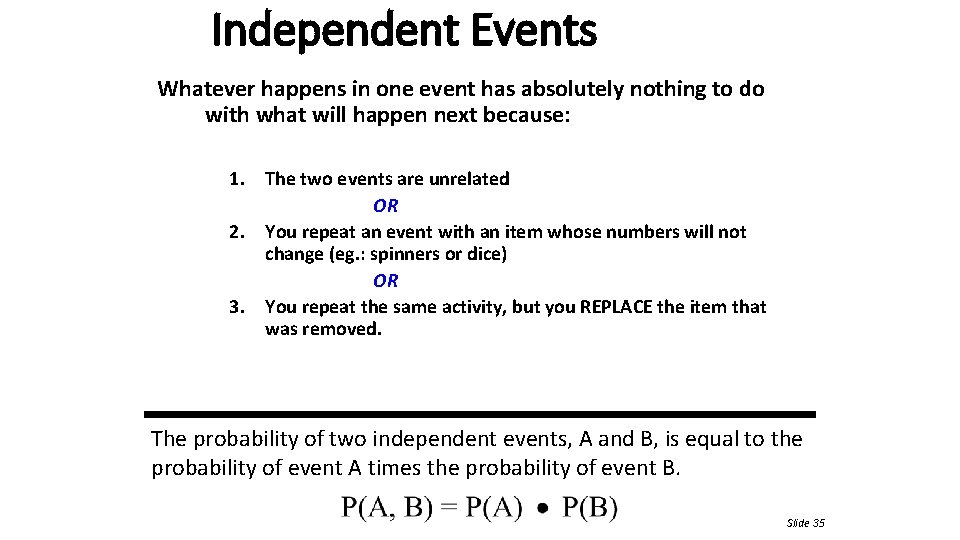

Independent Events Whatever happens in one event has absolutely nothing to do with what will happen next because: 1. The two events are unrelated OR 2. You repeat an event with an item whose numbers will not change (eg. : spinners or dice) OR 3. You repeat the same activity, but you REPLACE the item that was removed. The probability of two independent events, A and B, is equal to the probability of event A times the probability of event B. Slide 35

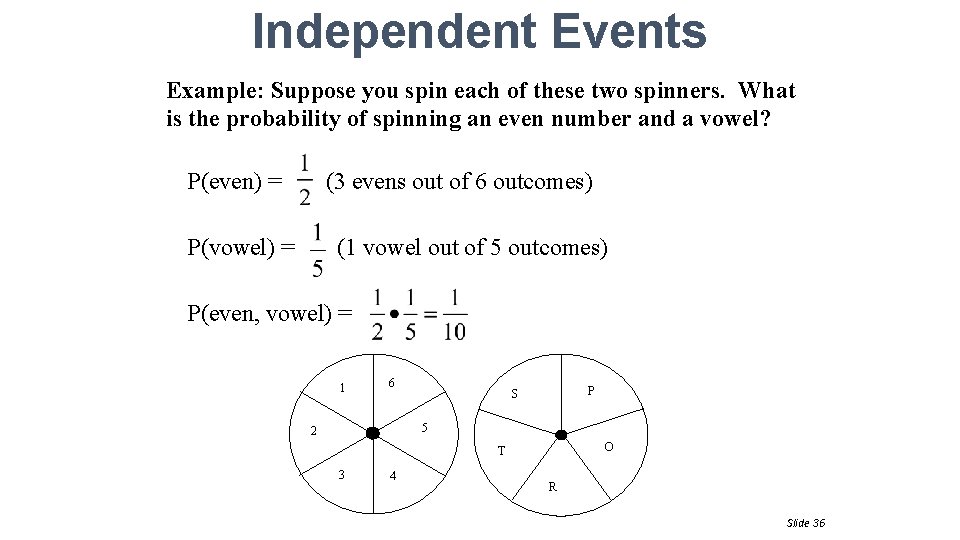

Independent Events Example: Suppose you spin each of these two spinners. What is the probability of spinning an even number and a vowel? P(even) = (3 evens out of 6 outcomes) (1 vowel out of 5 outcomes) P(vowel) = P(even, vowel) = 1 6 P S 5 2 O T 3 4 R Slide 36

Independence • The probability of independent events A, B and C is given by: P(A, B, C) = P(A)P(B)P(C) A and B are independent, if knowing that A has happened does not say anything about B happening Pattern Classification, Chapter 1 37

PROBABILITIES OF DEPENDENT EVENTS • Two events A and B are dependent events if the occurrence of one affects the occurrence of the other. • The probability that B will occur given that A has occurred is called the conditional probability of B given A and is written P(B|A).

Dependent Event • What happens during the second event depends upon what happened before. • In other words, the result of the second event will change because of what happened first. The probability of two dependent events, A and B, is equal to the probability of event A times the probability of event B. However, the probability of event B now depends on event A. P(A&B) = P(A) * P(B/A) Slide 39

Probability of Three Dependent Events • You and two friends go to a restaurant and order a sandwich. The menu has 10 types of sandwiches and each of you is equally likely to order any type. What is the probability that each of you orders a different type?

• Let event A be that you order a sandwich, event B be that one friend orders a different type, and event C be that your other friend orders a third type. These events are dependent. So, the probability that each of you orders a different type is: • P(A and B and C) = • P(A) • P(B|A) • P(C|A and B)= • 10/10 * 9/10 * 8/10 = • 18/25 =. 72

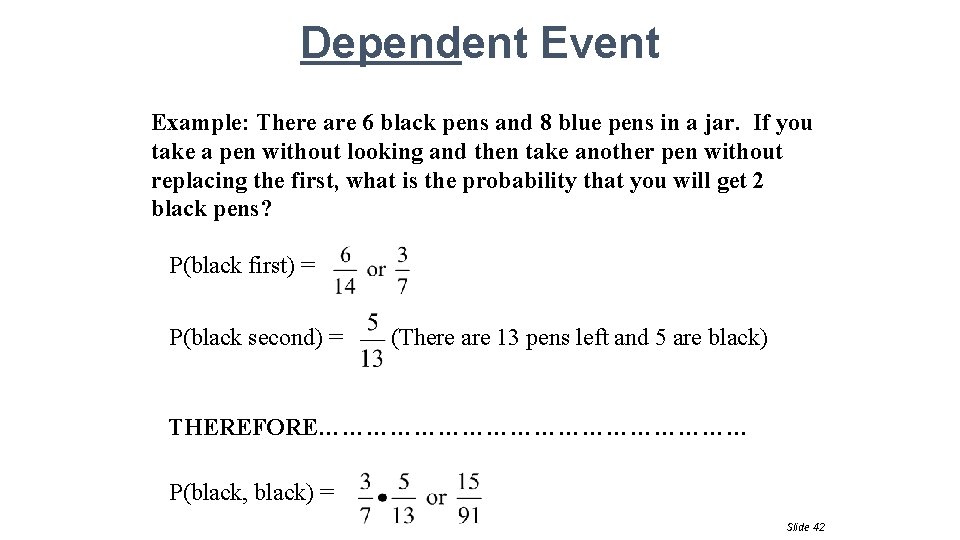

Dependent Event Example: There are 6 black pens and 8 blue pens in a jar. If you take a pen without looking and then take another pen without replacing the first, what is the probability that you will get 2 black pens? P(black first) = P(black second) = (There are 13 pens left and 5 are black) THEREFORE……………………… P(black, black) = Slide 42

TEST YOURSELF Are these dependent or independent events? 1. Tossing two dice and getting a 6 on both of them. 2. You have a bag of marbles: 3 blue, 5 white, and 12 red. You choose one marble out of the bag, look at it then put it back. Then you choose another marble. 3. You have a basket of socks. You need to find the probability of pulling out a black sock and its matching black sock without putting the first sock back. 4. You pick the letter Q from a bag containing all the letters of the alphabet. You do not put the Q back in the bag before you pick another tile. Slide 43

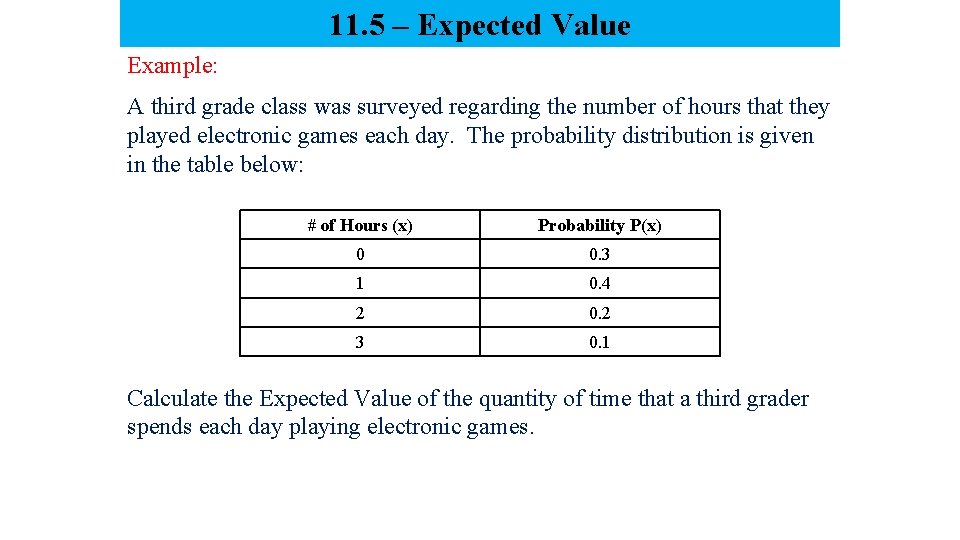

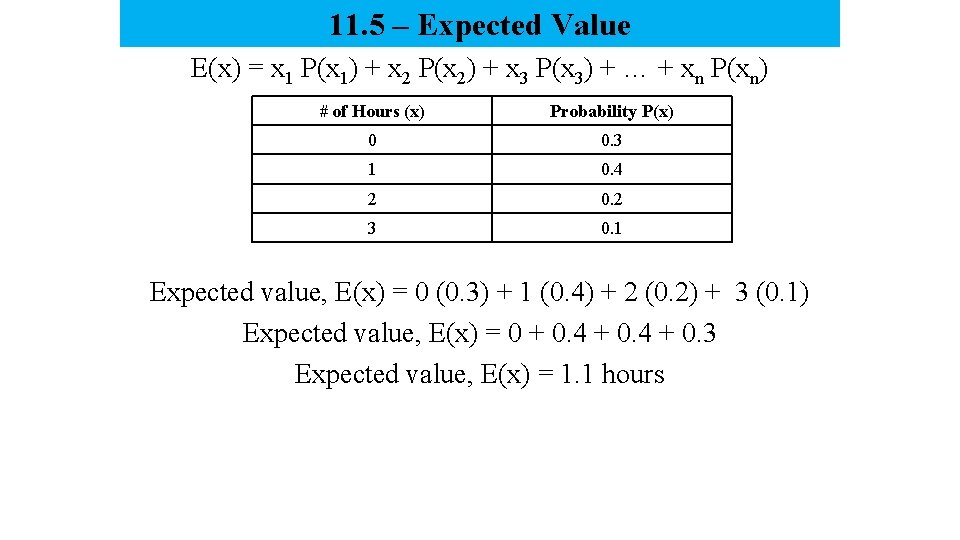

11. 5 – Expected Value The Expected Value of x is the sum of the products of the values of x and their corresponding probabilities. E(x) = x 1 P(x 1) + x 2 P(x 2) + x 3 P(x 3) + … + xn P(xn) The expected value is a calculation that serves as the best prediction of a value. It is the probability-weighted average of all possible outcomes. The expected value of a possible future event assists in making mathematically sound decisions. It is often used when making investments, determining a price for numerous services, prioritizing events, and in calculating Return on Investment.

11. 5 – Expected Value Example: A third grade class was surveyed regarding the number of hours that they played electronic games each day. The probability distribution is given in the table below: # of Hours (x) Probability P(x) 0 0. 3 1 0. 4 2 0. 2 3 0. 1 Calculate the Expected Value of the quantity of time that a third grader spends each day playing electronic games.

11. 5 – Expected Value E(x) = x 1 P(x 1) + x 2 P(x 2) + x 3 P(x 3) + … + xn P(xn) # of Hours (x) Probability P(x) 0 0. 3 1 0. 4 2 0. 2 3 0. 1 Expected value, E(x) = 0 (0. 3) + 1 (0. 4) + 2 (0. 2) + 3 (0. 1) Expected value, E(x) = 0 + 0. 4 + 0. 3 Expected value, E(x) = 1. 1 hours

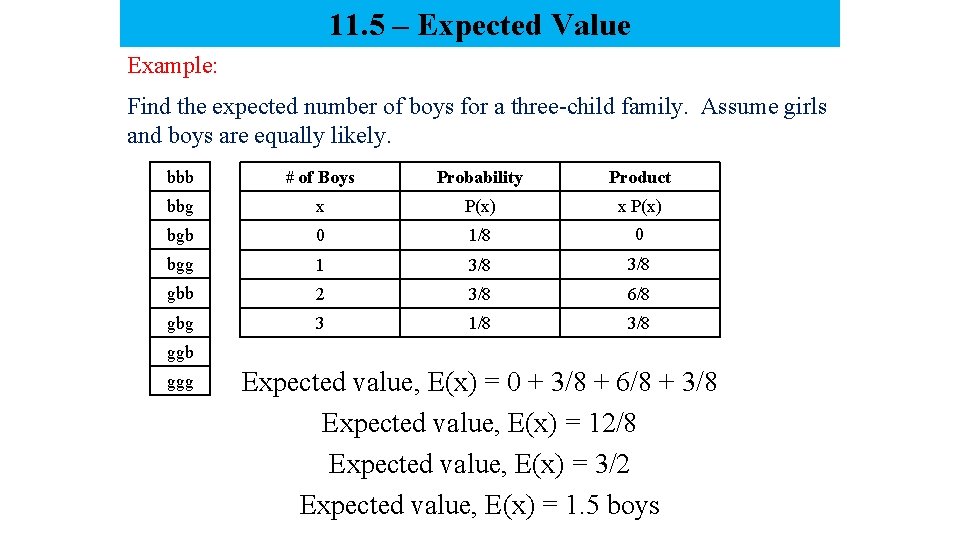

11. 5 – Expected Value Example: Find the expected number of boys for a three-child family. Assume girls and boys are equally likely. bbb # of Boys Probability Product bbg x P(x) bgb 0 1/8 0 bgg 1 3/8 gbb 2 3/8 6/8 gbg 3 1/8 3/8 ggb ggg Expected value, E(x) = 0 + 3/8 + 6/8 + 3/8 Expected value, E(x) = 12/8 Expected value, E(x) = 3/2 Expected value, E(x) = 1. 5 boys

- Slides: 47