INTRODUCTION TO SPACE SCIENCE PHY 209 ATMOSPHERIC SPACE

- Slides: 29

INTRODUCTION TO SPACE SCIENCE (PHY 209) ATMOSPHERIC SPACE LECTURE FOUR Prof. Theodora. O. BELLO

LECTURE OVERVIEW ü ü ü Description of the Atmospheric Space Explanation of the Outer Space Description of Geospace Explanation of the History of Comets Description of the Meteorites Explanation of the Impact of Comets and Meteorites on Earth

COURSE OBJECTIVES After going through the course, students should be able to: ü Describe the Atmospheric Space ü Explain the Outer Space ü Describe the Geospace ü Explain the History of Comets ü Describe the Meteorites ü Explain the Impact of Comets and Meteorites on Earth

THE ATMOSPHERIC SPACE ü The atmosphere is made up of a mixture of gases (mostly nitrogen, oxygen, argon and carbon dioxide ü It is the only thing that keeps us from being burned to death every day ü It helps to bring the rain that plants need to survive ü It holds the oxygen that we need to breath. ü It is a collection of gases that makes the earth habitable. ü The atmosphere consists of 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, 1% water vapor, and a small amount of other trace gases like argon, helium, Krypton, methane, neon SO 2 and carbon monoxide

ATMOSPHERIC SPACE ü All these gases combine to absorb ultraviolet radiation from the Sun and warm the planet’s surface through heat retention ü It reaches over 500 km above the surface of the planet. ü It has mass of about 5× 1018 kg; 75% of this is within 11 km of the surface. ü It becomes thinner as one goes higher ü There is no clear line demarcating the atmosphere from space; however, the Karman line, at 100 km, is often regarded as the boundary between atmosphere and outer space

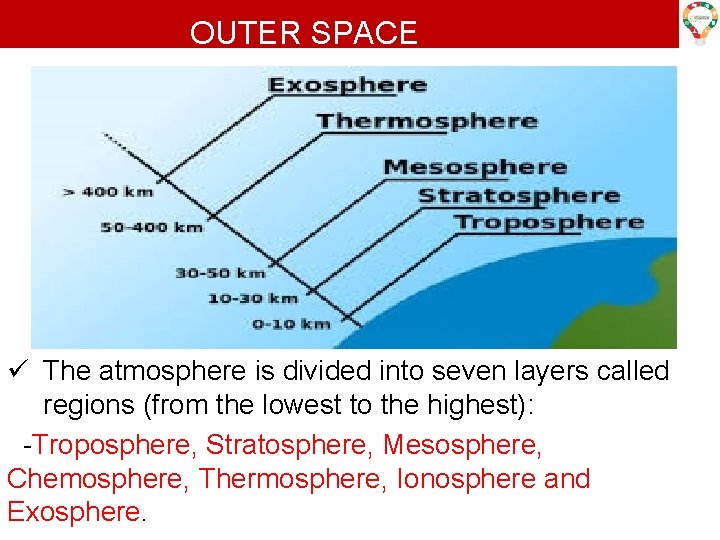

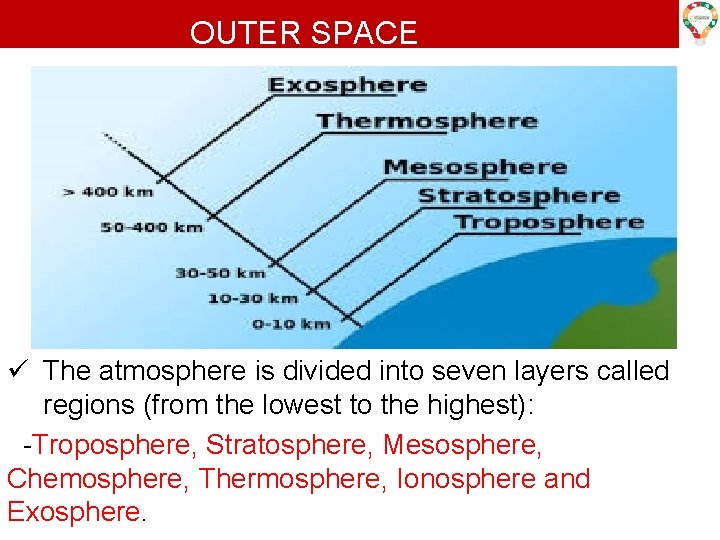

OUTER SPACE ü The atmosphere is divided into seven layers called regions (from the lowest to the highest): -Troposphere, Stratosphere, Mesosphere, Chemosphere, Thermosphere, Ionosphere and Exosphere.

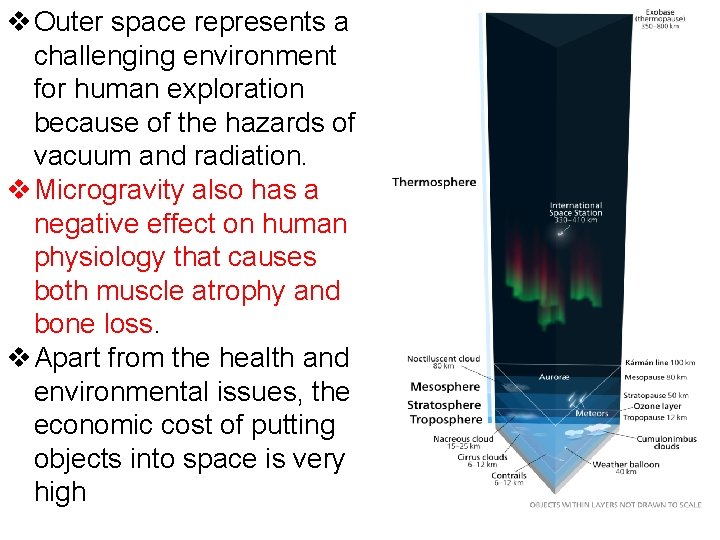

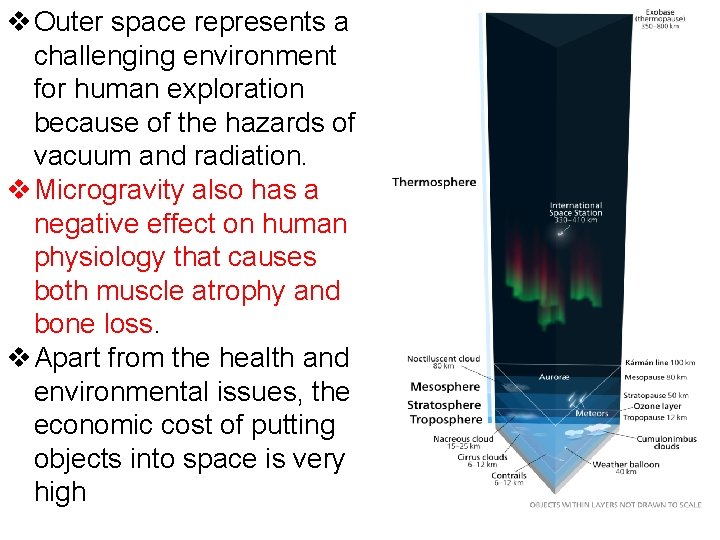

v Outer space represents a challenging environment for human exploration because of the hazards of vacuum and radiation. v Microgravity also has a negative effect on human physiology that causes both muscle atrophy and bone loss. v Apart from the health and environmental issues, the economic cost of putting objects into space is very high

THE OUTER SPACE 1 ü There is no exact boundary between the atmosphere and outer space. ü The Outer space, or simply space, is the expanse that exists beyond the earth and between celestial bodies. ü It is not completely empty but it is a hard vacuum containing a low density of particles, predominantly a plasma of hydrogen and helium ü It also contains electromagnetic radiation, magnetic fields, neutrinos, dust and cosmic rays ü The baseline temperature of outer space, as set by the background radiation from the Big Bang, is 2. 7 kelvins (− 270. 45 °C; − 454. 81 °F). ü The plasma between galaxies accounts for about half of the baryonic ordinary matter in the number density less than one hydrogen atom per cubic meter and a temperature of millions of kelvins

OUTER SPACE 2 ü Local concentrations of matter have condensed into stars and galaxies. ü 90% of the mass in most galaxies is in an unknown form, called dark matter ü This interacts with other matter through gravitational but not electromagnetic forces ü Observations shows that the majority of the mass-energy in the observable universe is dark energy ü Intergalactic space takes up most of the volume of the universe ü Galaxies and star systems consist almost entirely of empty space.

• OUTER SPACE 3 ü Outer space has effectively no friction ü It allowing stars, planets, and moons to move freely along their ideal orbits, following the initial formation stage. ü The deep vacuum of intergalactic space is not devoid of matter; it contains a few hydrogen atoms per cubic meter. ü Comparison shows that the air humans breathe contains about 1025 molecules per cubic meter. ü The low density of matter in outer space implies that electromagnetic radiation can travel great distances without being scattered ü The mean free path of a photon in intergalactic space is about 1023 km, or 10 billion light years ü Absorption and scattering of photons by dust and gas, is an important factor in galactic and intergalactic astronomy

OUTER SPACE 3 ü Stars, planets, and moons retain their atmospheres by gravitational attraction, with no clearly delineation of the upper boundary in the atmospheres ü The density of atmospheric gas gradually decreases with distance from the object until it becomes indistinguishable from outer space ü The Earth's atmospheric pressure drops to about 0. 032 Pa at 100 km (62 miles) of altitude compared to 100, 000 Pa for the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition of standard pressure ü Above this altitude, isotropic gas pressure rapidly becomes insignificant when compared to radiation, pressure from the Sun and the dynamic pressure of the solar wind. ü The thermosphere in this range has large gradients of pressure, temperature and composition, and varies greatly due to space weather

OUTER SPACE 4 ü The temperature of outer space is measured in terms of the kinetic activity of the gas, as it is on Earth. ü The radiation of outer space has a different temperature than the kinetic temperature of the gas, meaning that the gas and radiation are not in thermodynamic equilibrium ü All of the observables in the universe is filled with photons that were created during the Big bang, which is known as the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB). (There is quite likely a correspondingly large number of neutrinos called the cosmic neutrino background) ü The current black body temperature of the background radiation is about 3 o. K (− 270 C; − 454 o. F). ü The gas temperatures in outer space are always at least the temperature of the CMB but can be much higher (e. g. the corona of the Sun reaches temperatures over 1. 2– 2. 6 milliono. K

OUTER SPACE 5 ü Magnetic fields have been detected in the space around every class of celestial object ü Star formation in spiral galaxies can generate small-scale dynamos, creating turbulent magnetic field strengths of around 5– 10 μG. ü The Davis-Greenstein effect causes elongated dust grains to align themselves with a galaxy's magnetic field, resulting in weak optical polarization. ü This has been used to show ordered magnetic fields exist in several nearby galaxies ü Magneto-hydrodynamic processes in active elliptical galaxies produce their characteristic jets and radio lobes ü Non-thermal radio sources were detected even among the most distant, high-z sources, indicating the presence of magnetic fields

OUTER SPACE 6 ü Outside a protective atmosphere and magnetic field, there are few obstacles to the passage through space of energetic subatomic particles known as cosmic rays ü These particles have energies ranging from about 106 e. V up to an extreme 1020 e. V of ultra-high-energy cosmic rays. ü The peak flux of cosmic rays occurs at energies of about 109 e. V, with approximately 87% protons, 12% helium nuclei and 1% heavier nuclei. ü In the high energy range, the flux of electrons is only about 1% of that of protons. ü Cosmic rays can damage electronic components and pose a health threat to space travelers. ü According to astronauts (Don Pettit), space has a burned / metallic odor that clings to their suits and equipment, similar to the scent of an arc welding torch

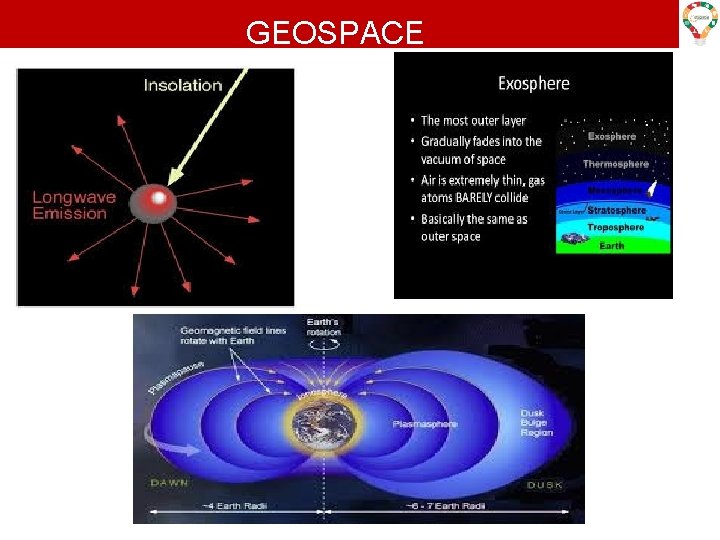

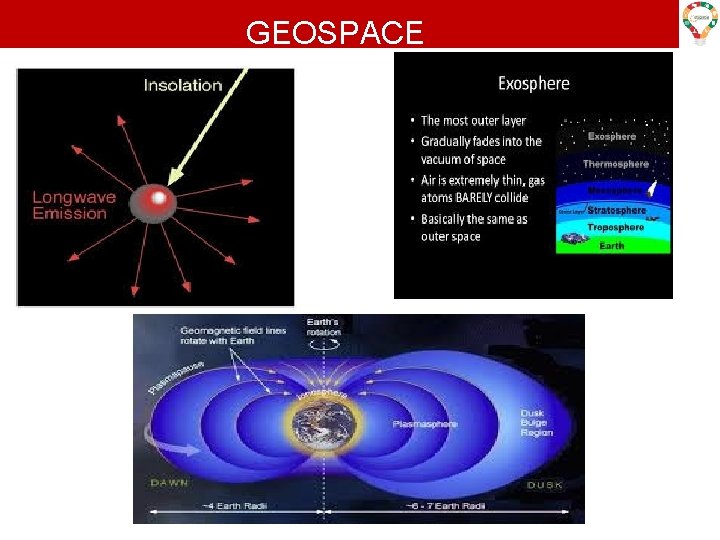

GEOSPACE ü Geospace is the region of outer space near Earth, including the upper atmosphere and magnetosphere the Van Allen radiation belts lie within the geospace. ü The outer boundary of geospace is the magnetopause, which forms an interface between the Earth's magnetosphere and the solar wind. ü The inner boundary is the ionosphere. ü The variable space-weather conditions of geospace are affected by the behaviour of the Sun and the solar wind ü The subject of geospace is interlinked with heliophysics (the study of the Sun and its impact on the planets of the Solar System) ü The day-side magnetopause is compressed by solar-wind pressure—the subsolar distance from the center of the Earth is typically 10 Earth radii

GEOSPACE ü On the night side, the solar wind stretches the magnetosphere to form a magnetotail that sometimes extends out to more than 100– 200 Earth radii. ü Roughly four days of each month, the lunar surface is shielded from the solar wind as the Moon passes through the magnetotail ü Geospace is populated by electrically charged particles at very low densities ü The motions of which are controlled by the Earth’s magnetic field. These plasmas form a medium from which storm-like disturbances powered by the solar wind can drive electrical currents into the Earth's upper atmosphere. ü Geomagnetic storms can disturb two regions of geospace, the radiation belts and the ionosphere.

GEOSPACE ü These storms increase fluxes of energetic electrons that can permanently damage satellite electronics, interfering with shortwave radio communication and GPS location and timing. ü Magnetic storms can also be a hazard to astronauts, even in low Earth orbit. ü They also create aurorae seen at high latitudes in an oval surrounding the geomagnetic poles ü Although it meets the definition of outer space, the atmospheric density within the first few hundred kilometers above the Kármán line is still sufficient to produce significant drag on satellites. ü This region contains material left over from previous manned and unmanned launches that are a potential hazard to spacecraft. ü Some of this debris re-enters Earth's atmosphere periodically

GEOSPACE

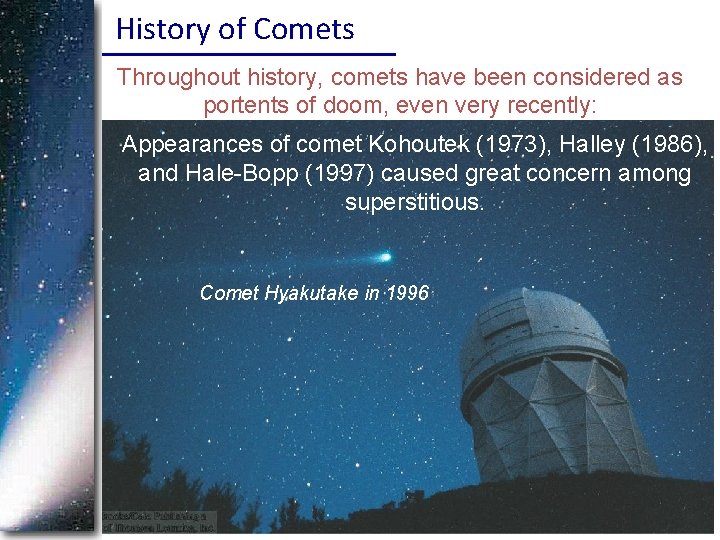

History of Comets Throughout history, comets have been considered as portents of doom, even very recently: Appearances of comet Kohoutek (1973), Halley (1986), and Hale-Bopp (1997) caused great concern among superstitious. Comet Hyakutake in 1996

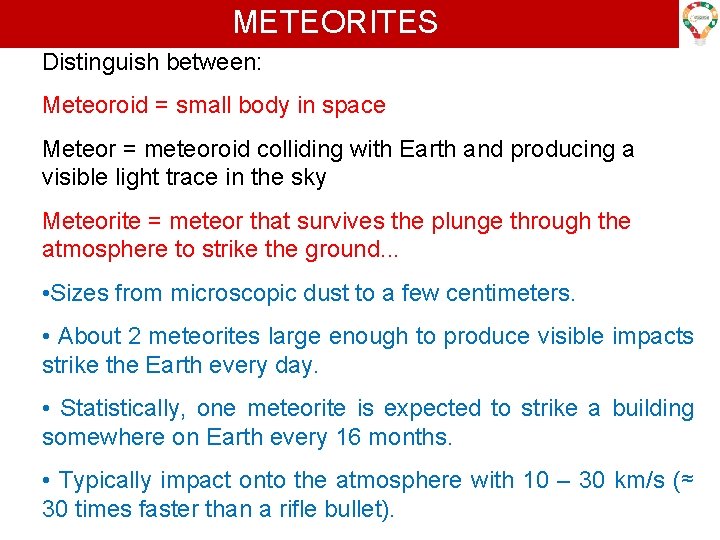

METEORITES Distinguish between: Meteoroid = small body in space Meteor = meteoroid colliding with Earth and producing a visible light trace in the sky Meteorite = meteor that survives the plunge through the atmosphere to strike the ground. . . • Sizes from microscopic dust to a few centimeters. • About 2 meteorites large enough to produce visible impacts strike the Earth every day. • Statistically, one meteorite is expected to strike a building somewhere on Earth every 16 months. • Typically impact onto the atmosphere with 10 – 30 km/s (≈ 30 times faster than a rifle bullet).

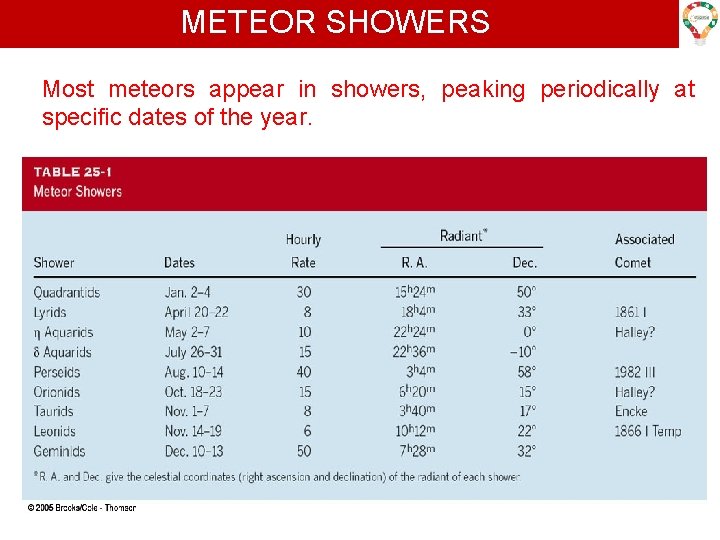

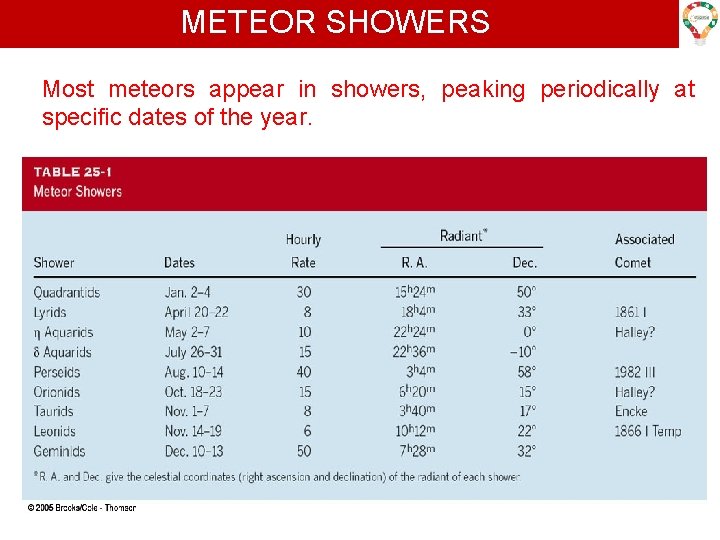

METEOR SHOWERS Most meteors appear in showers, peaking periodically at specific dates of the year.

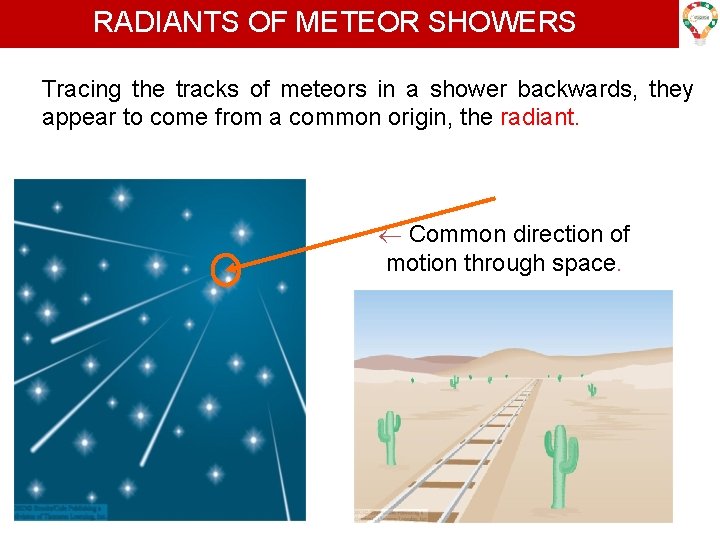

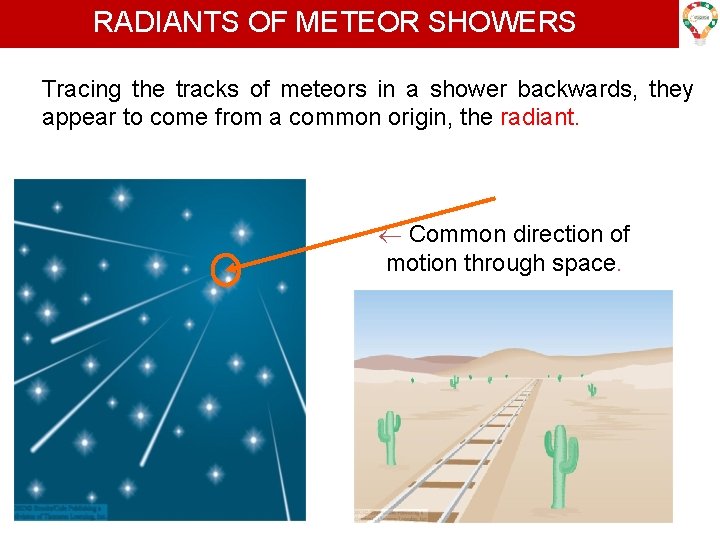

RADIANTS OF METEOR SHOWERS Tracing the tracks of meteors in a shower backwards, they appear to come from a common origin, the radiant. Common direction of motion through space.

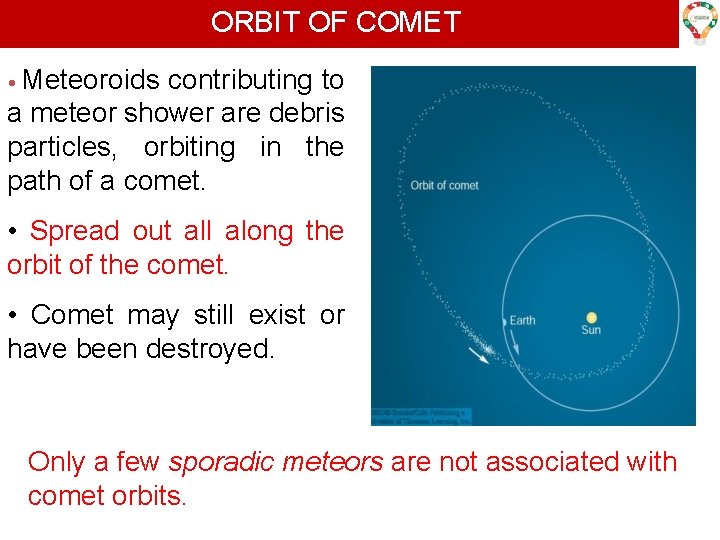

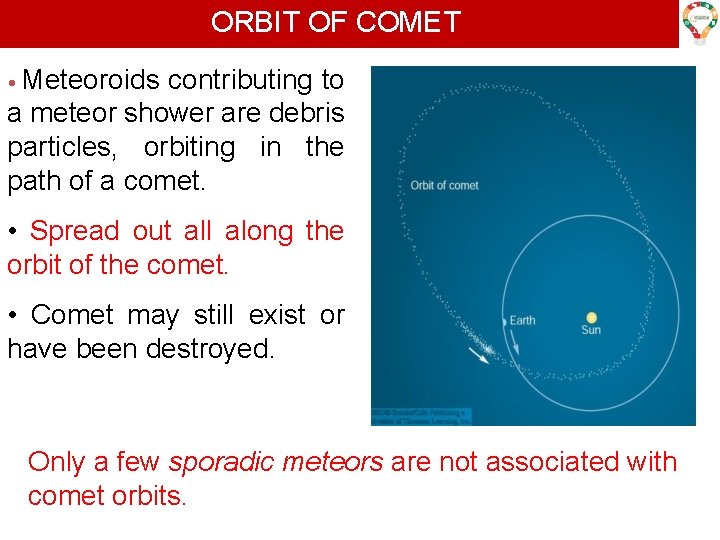

ORBIT OF COMET • Meteoroids contributing to a meteor shower are debris particles, orbiting in the path of a comet. • Spread out all along the orbit of the comet. • Comet may still exist or have been destroyed. Only a few sporadic meteors are not associated with comet orbits.

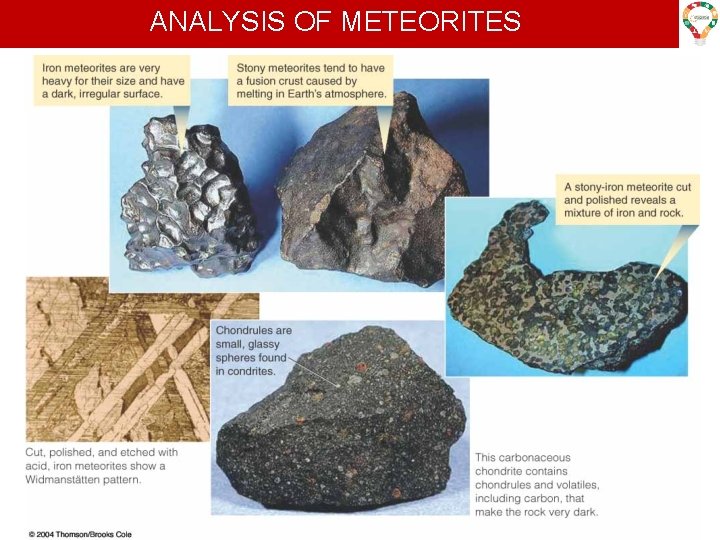

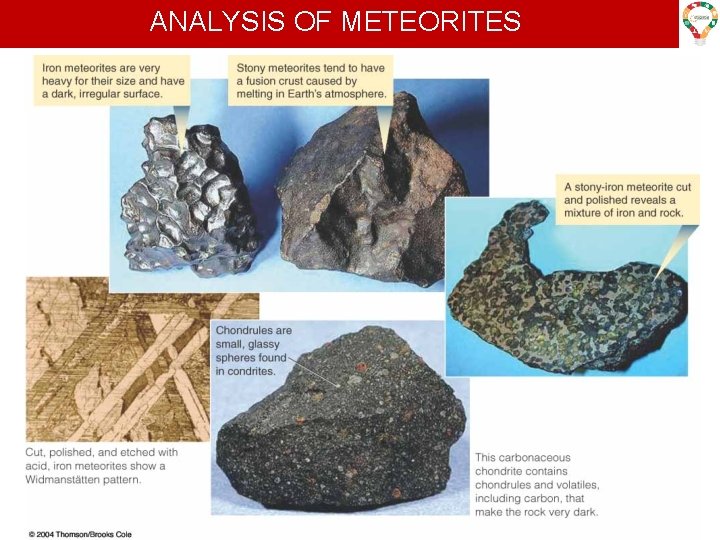

ANALYSIS OF METEORITES

THE ORIGINS OF METEORITES Probably formed in the solar nebula, ~ 4. 6 billion years ago. • Almost certainly not from comets (in contrast to meteors in meteor showers!). • Probably fragments of stony-iron planetesimals • Some melted by heat produced by 26 Al decay (half-life ~ 715, 000 yr). • 26 Al possibly provided by a nearby supernova, just a few 100, 000 years before formation of the solar system •

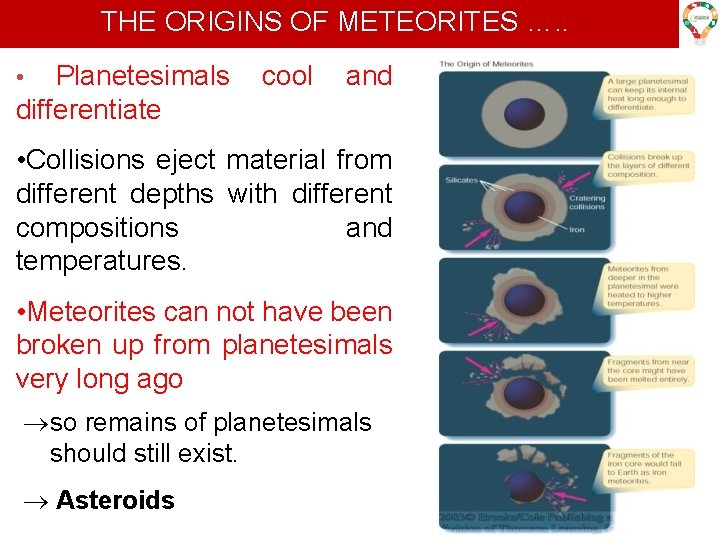

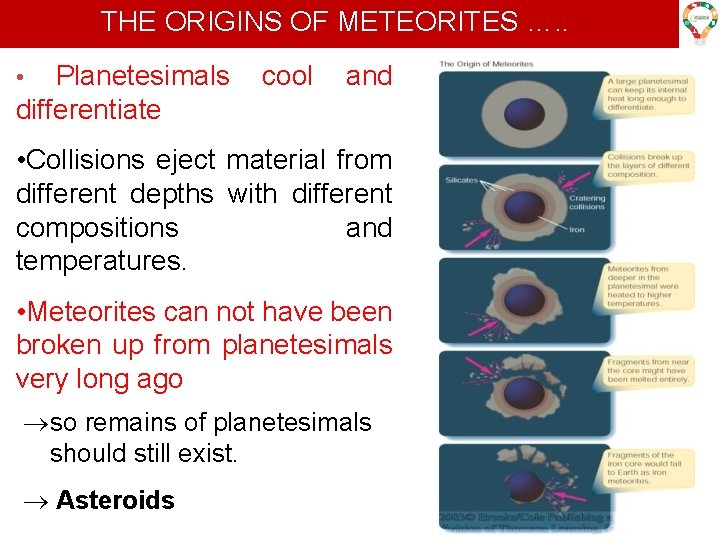

THE ORIGINS OF METEORITES …. . Planetesimals differentiate • cool and • Collisions eject material from different depths with different compositions and temperatures. • Meteorites can not have been broken up from planetesimals very long ago so remains of planetesimals should still exist. Asteroids

REVISION QUESTIONS • Mention and describe types of Meteorites • Discuss the characteristics of two layers of the Outer Space

REFERENCES 1. Murray, R. S. (1982). Schuam’s Outline of Theory and Problems of Theoretical Mechanics. Mc. Graw Book Company, New York, pp 45 -49 2. Gregory, R. D. (2006). Classical Mechanics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. www. cambridge. org/9780521826785, pp 357 -376

CONCLUSION