Introduction to Logic Herbrand Logic Proofs Michael Genesereth

Introduction to Logic Herbrand Logic Proofs Michael Genesereth Computer Science Department Stanford University

Propositional Logic {m ⇒ p Ú q, p ⇒ q} ⊨ m ⇒ q? 2

Relational Logic {p(a) ∨ p(b), ∀x. (p(x) ⇒ q(x))} ⊨ ∃x. q(x)?

Herbrand Logic Object constants: n Binary relation constants: k Factoids in Herbrand Base: infinite Interpretations: infinite 4

Herbrand Proofs

Logical Rules of Inference Negation Introduction Negation Elimination And Introduction And Elimination Or Introduction Or Elimination Assumption Implication Elimination Biconditional Introduction Biconditional Elimination

Rules of Inference for Quantifiers Universal Introduction Universal Elimination Existential Introduction Existential Elimination Domain Closure Induction (Linear, Tree, Structural) New!!

Structured Proof A structured proof of a conclusion from a set of premises is a sequence of (possibly nested) sentences terminating in an occurrence of the conclusion at the top level of the proof. Each step in the proof must be either (1) a premise (at the top level), (2) an assumption, or (3) the result of applying an ordinary or structured rule of inference to earlier items in the sequence (subject to the constraints given above). If there exists a proof of a sentence φ from a set Δ of premises using the rules of inference in Herbrand, we say that φ is provable from Δ (written Δ ⊢Herbrand φ).

Example - Spin

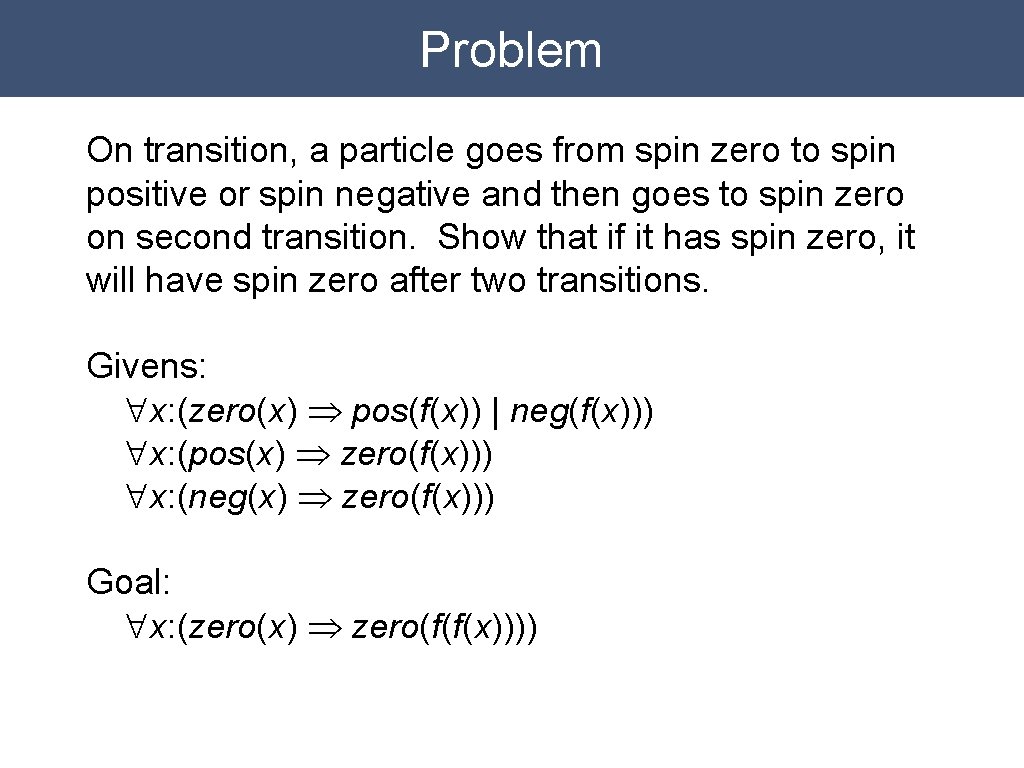

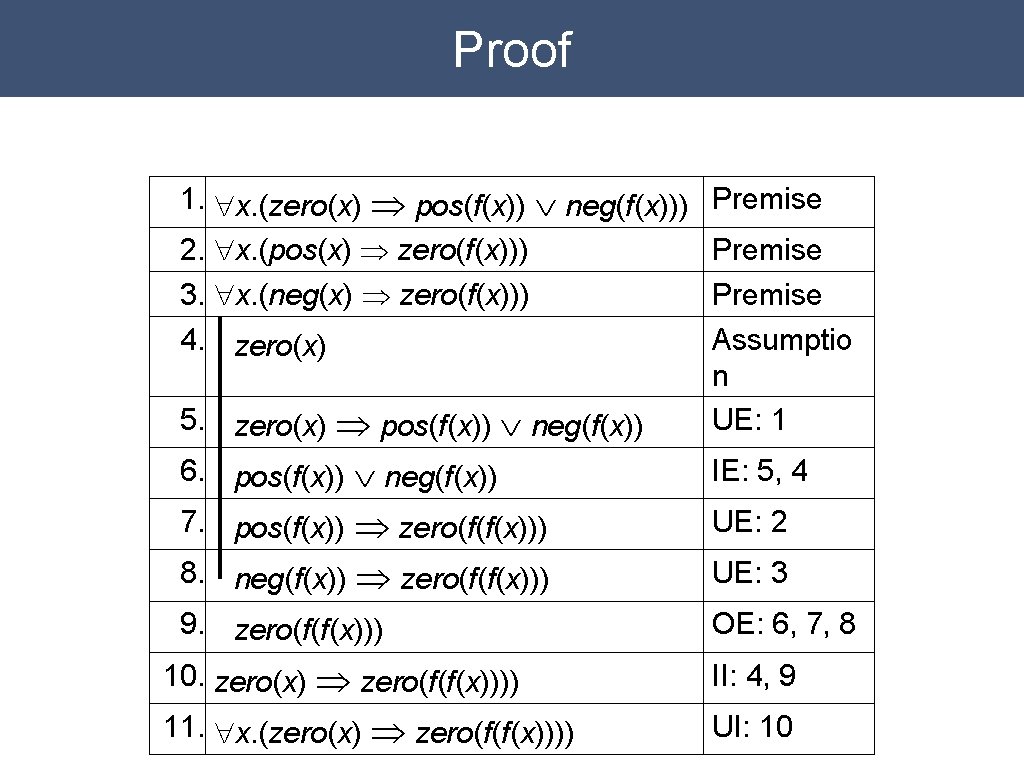

Problem On transition, a particle goes from spin zero to spin positive or spin negative and then goes to spin zero on second transition. Show that if it has spin zero, it will have spin zero after two transitions. Givens: "x: (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) | neg(f(x))) "x: (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) "x: (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Goal: "x: (zero(x) Þ zero(f(f(x))))

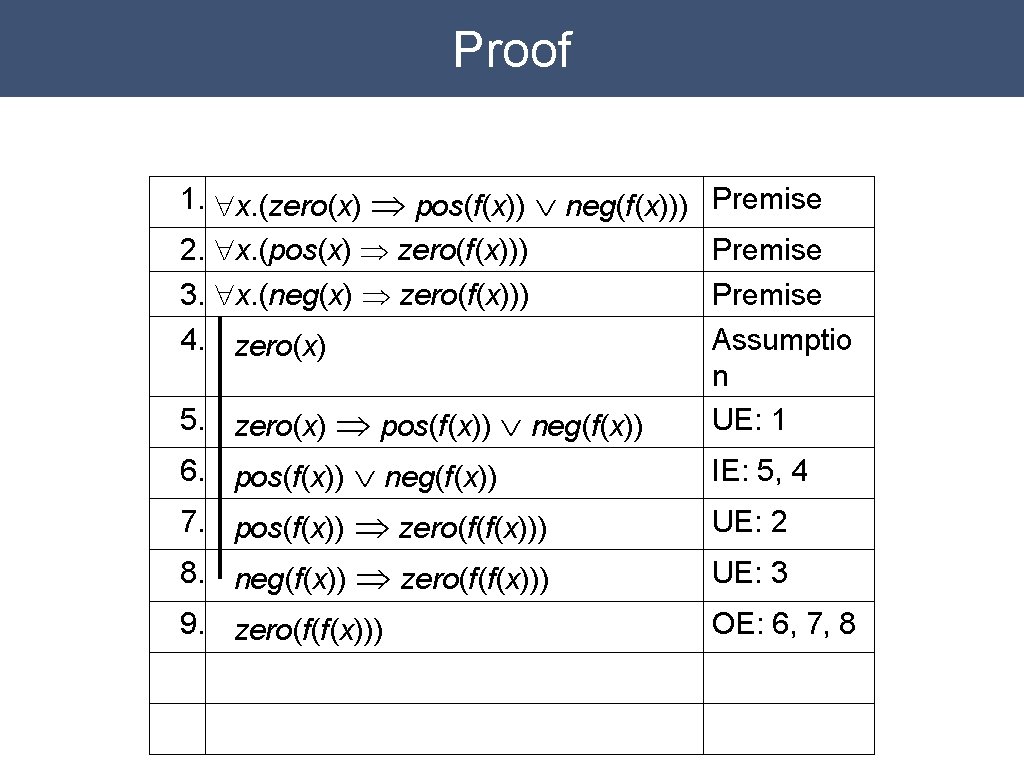

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n 5. zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) UE: 1

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n 5. zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) UE: 1 6. pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) IE: 5, 4

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n 5. zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) UE: 1 6. pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) IE: 5, 4 7. pos(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 2 8. neg(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 3

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n 5. zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) UE: 1 6. pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) IE: 5, 4 7. pos(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 2 8. neg(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 3 9. zero(f(f(x))) OE: 6, 7, 8

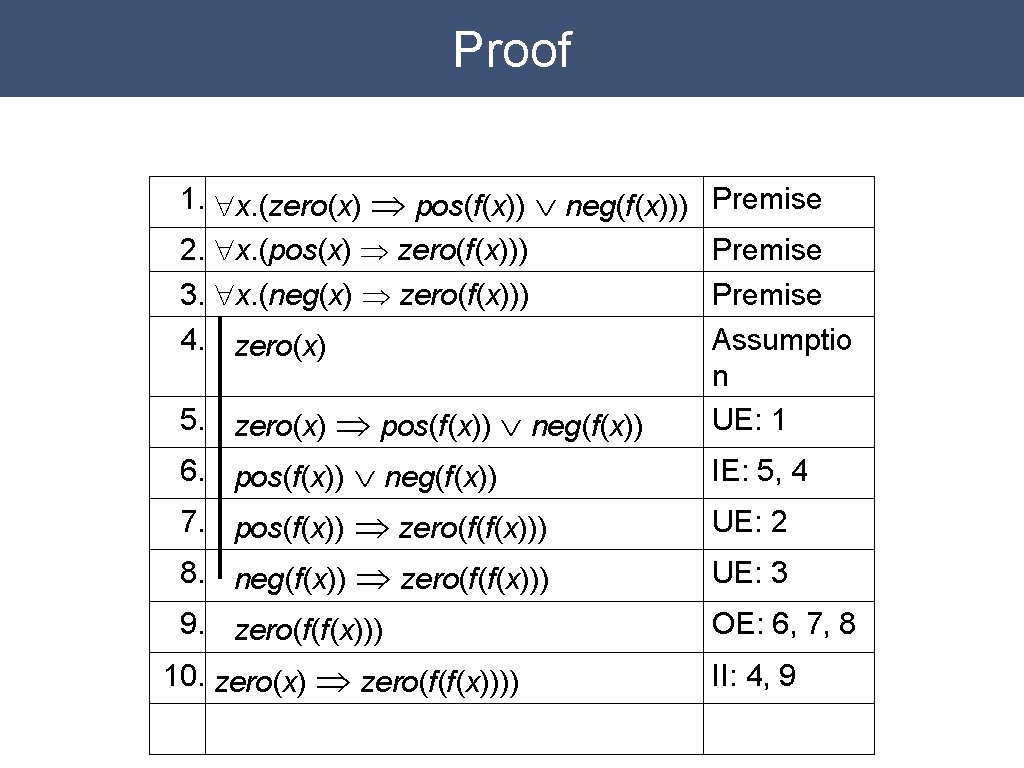

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n 5. zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) UE: 1 6. pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) IE: 5, 4 7. pos(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 2 8. neg(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 3 9. zero(f(f(x))) OE: 6, 7, 8 10. zero(x) Þ zero(f(f(x)))) II: 4, 9

Proof 1. "x. (zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x))) Premise 2. "x. (pos(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 3. "x. (neg(x) Þ zero(f(x))) Premise 4. zero(x) Assumptio n 5. zero(x) Þ pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) UE: 1 6. pos(f(x)) Ú neg(f(x)) IE: 5, 4 7. pos(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 2 8. neg(f(x)) Þ zero(f(f(x))) UE: 3 9. zero(f(f(x))) OE: 6, 7, 8 10. zero(x) Þ zero(f(f(x)))) 11. "x. (zero(x) Þ zero(f(f(x)))) II: 4, 9 UI: 10

Analysis

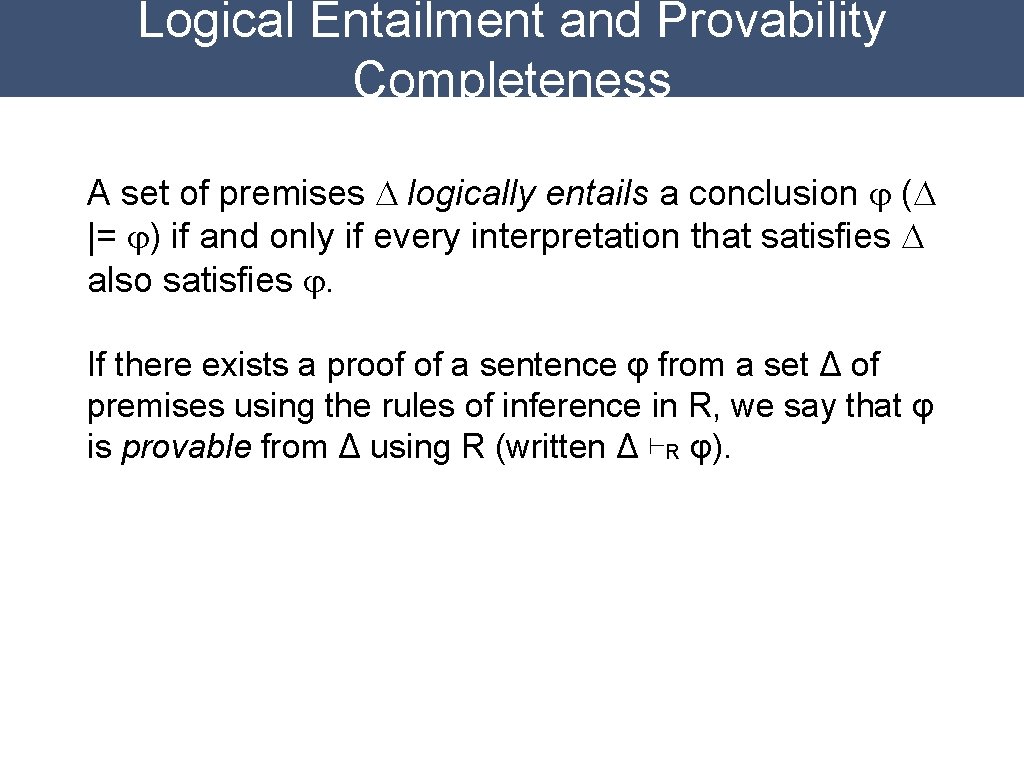

Logical Entailment and Provability Completeness A set of premises D logically entails a conclusion j (D |= j) if and only if every interpretation that satisfies D also satisfies j. If there exists a proof of a sentence φ from a set Δ of premises using the rules of inference in R, we say that φ is provable from Δ using R (written Δ ⊢R φ).

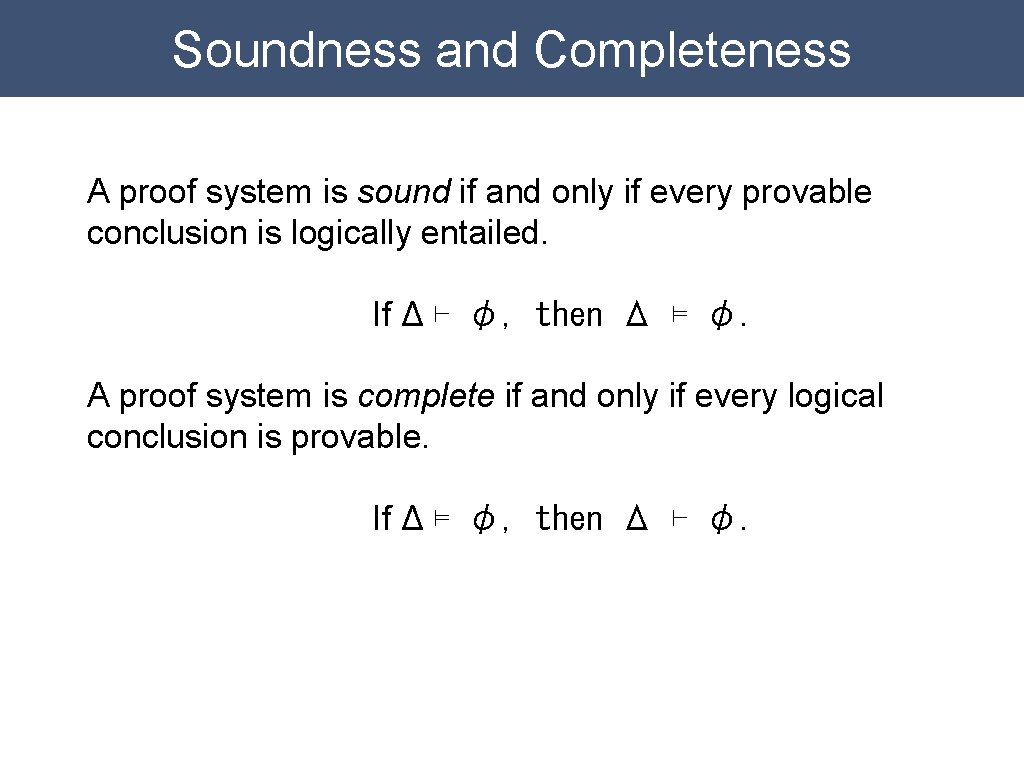

Soundness and Completeness A proof system is sound if and only if every provable conclusion is logically entailed. If Δ ⊢ φ, then Δ ⊨ φ. A proof system is complete if and only if every logical conclusion is provable. If Δ ⊨ φ, then Δ ⊢ φ.

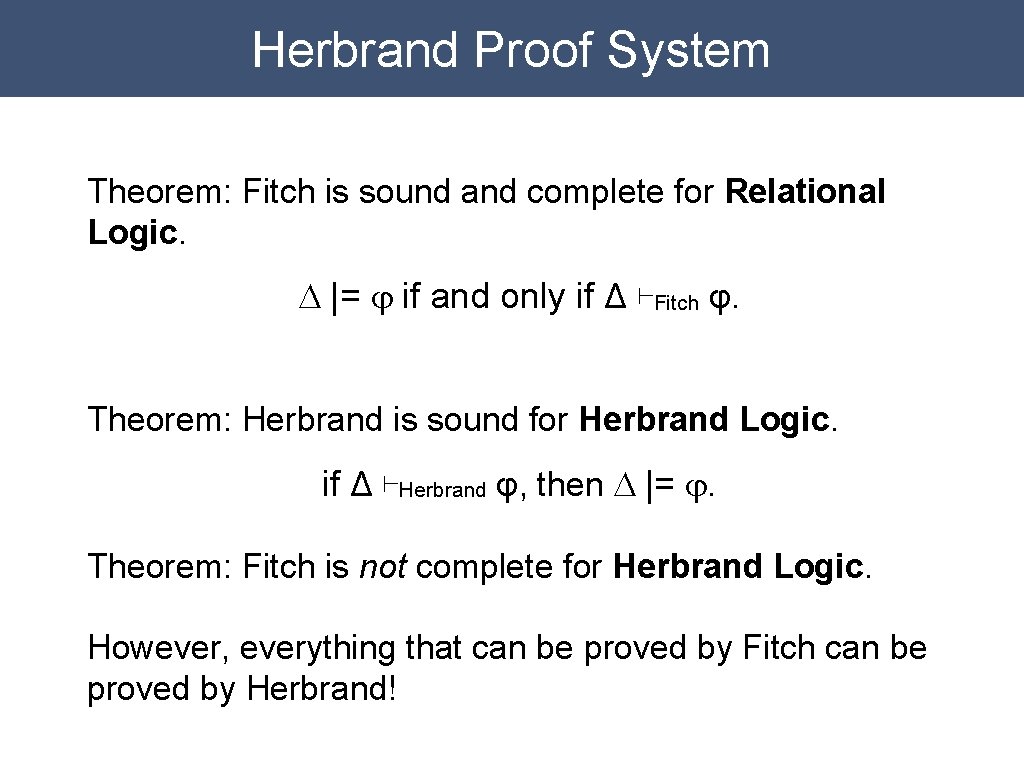

Herbrand Proof System Theorem: Fitch is sound and complete for Relational Logic. D |= j if and only if Δ ⊢Fitch φ. Theorem: Herbrand is sound for Herbrand Logic. if Δ ⊢Herbrand φ, then D |= j. Theorem: Fitch is not complete for Herbrand Logic. However, everything that can be proved by Fitch can be proved by Herbrand!

Good News HL is highly expressive. For example, possible to axiomatize arithmetic as a finite set of axioms. This is not possible with Relational Logic and in other logics (e. g. First-Order Logic).

Bad News The question of unsatisfiability and the question of logical entailment for HL are not even semidecidable.

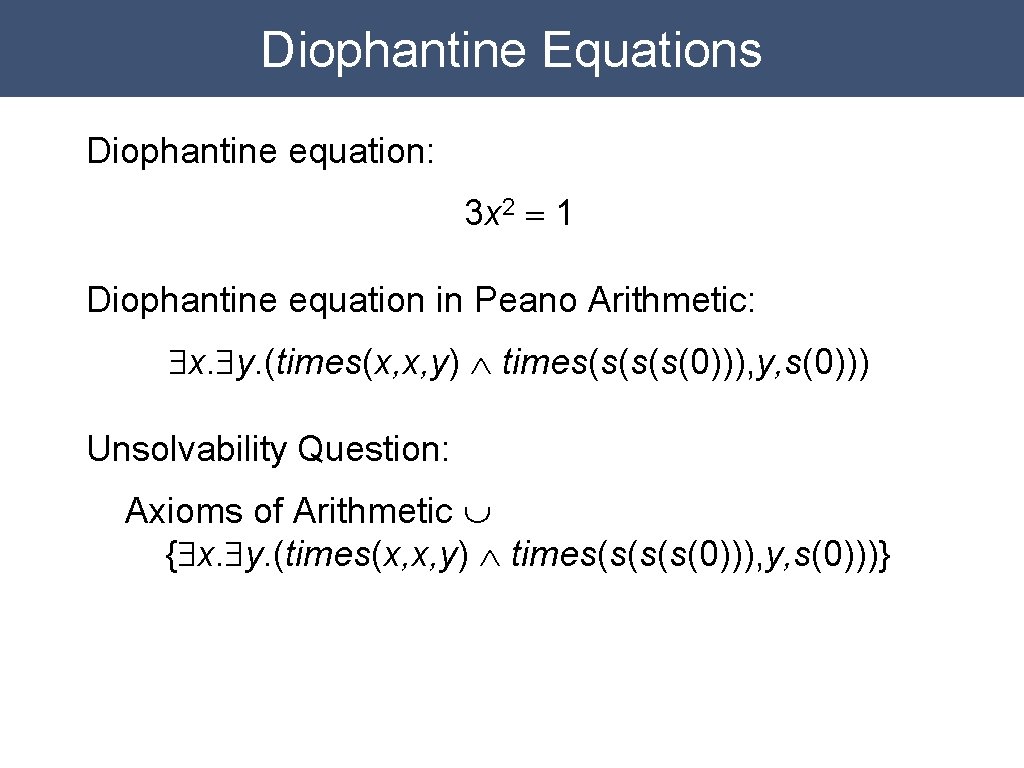

Diophantine Equations Diophantine equation: 3 x 2 = 1 Diophantine equation in Peano Arithmetic: $x. $y. (times(x, x, y) Ù times(s(0))), y, s(0))) Unsolvability Question: Axioms of Arithmetic È {$x. $y. (times(x, x, y) Ù times(s(0))), y, s(0)))}

HL Not Even Semidecidable It is known that the question of unsolvability of Diophantine equations is not semidecidable. Since we can represent the question of unsolvability of Diophantine equations in Herbrand Logic, if we could determine the unsatisfiability of sentences in Herbrand Logic, we could answer questions of unsolvability of Diophantine equations.

- Slides: 27