Introduction to Logic By Prof Dr Rauf I

Introduction to Logic By Prof. Dr. Rauf. I. Azam Lecture#2

Definitions Logic: Logic is the study of the methods and principles used to distinguish correct from incorrect reasoning Ø Reasoning as an Art Ø Reasoning as a Science Proposition: An Assertion that something is (or is not) the case; all propositions are either true or false Ø It is raining (English) Ø Barsaat ho rhi hai (Hindi/Urdu) Ø Mazha peyyunnu (Malayalam)

Definitions Statement: The meaning of a declarative sentence at a particular time; in logic, the word “statement” is some times used instead of “proposition”. Ø Statement is not exact synonym of proposition Ø Some logicians prefer statement to proposition

Types of propositions Simple Proposition: A proposition making only one assertion. Compound Proposition: A proposition containing two or more simple propositions.

Continued Ø Conjunctive: A type of compound proposition; if true, then both of the component proposition must be true. e. g. Students of logic are intelligent and hardworking Ø Disjunctive Proposition: A type of compound proposition; if true, at least one of the component proposition must be true. Ø e. g. Students of logic are intelligent or hardworking e. g The upper house of parliaments are effective, or they are not effective. Hypothetical Proposition: A type of compound proposition; it is false only when the antecedent is true and the consequent is false. e. g If it is raining then the roads are wet

Arguments Propositions are the building block of which arguments are made. Inferences: A process of linking propositions by affirming one proposition by on the basis of the one or more other propositions Arguments: A structured group of propositions, reflecting an inference Premise: A proposition used in an argument to support some other propositions Conclusion: The proposition in an argument that the other propositions, the premises, support

Exercises Identify the premises and conclusions in the passages, each of which contains only one argument.

Deductive and Inductive Arguments All bats are mammals. All mammals are warm-blooded. So, all bats are warm-blooded. All arguments are deductive or inductive. Inductive arguments: Inductive arguments are formed when we infer some rule from several observed examples having one or more common characteristics. These arguments in which the conclusion is claimed or intended to follow only with some degree or probability from the premises. Deductive arguments: Process of drawing inference on the basis of an already formed rule is called deduction. These arguments in which the conclusion is claimed or intended to follow necessarily from the premises. Is the argument above deductive or inductive?

All bats are mammals. All mammals are warm-blooded. So, all bats are warm-blooded. Deductive. If the premises are true, the conclusion, logically, must also be true.

There are four tests that can be used to determine whether an argument is deductive or inductive: · the indicator word test · the strict necessity test · the common pattern test · the principle of charity test

Kristin is a law student. Most law students own laptops. So, probably Kristin owns a laptop. The indicator word test asks whethere any indicator words that provide clues whether a deductive or inductive argument is being offered. Common deduction indicator words include words or phrases like necessarily, logically, it must be the case that, and this proves that. Common induction indicator words include words or phrases like probably, likely, it is plausible to suppose that, it is reasonable to think that, and it's a good bet that. In the example above, the word probably shows that the argument is inductive.

No Texans are architects. No architects are Democrats. So, no Texans are Democrats. The strict necessity test asks whether the conclusion follows from the premises with strict logical necessity. If it does, then the argument is deductive. In this example, the conclusion does follow from the premises with strict logical necessity. Although the premises are both false, the conclusion does follow logically from the premises, because if the premises were true, then the conclusion would be true as well.

Either Kurt voted in the last election, or he didn't. Only citizens can vote. Kurt is not, and has never been, a citizen. So, Kurt didn't vote in the last election. The common pattern test asks whether the argument exhibits a pattern of reasoning that is characteristically deductive or inductive. If the argument exhibits a pattern of reasoning that is characteristically deductive, then the argument is probably deductive. If the argument exhibits a pattern of reasoning that is characteristically inductive, then the argument is probably inductive. In the example above, the argument exhibits a pattern of reasoning called "argument by elimination. " Arguments by elimination are arguments that seek to logically rule out various possibilities until only a single possibility remains. Arguments of this type are always deductive.

Arnie: Harry told me his grandmother recently climbed Mt. Everest. Sam: Well, Harry must be pulling your leg. Harry's grandmother is over 90 years old and walks with a cane. In this passage, there are no clear indications whether Sam's argument should be regarded as deductive or inductive. For arguments like these, we fall back on the principle of charity test. According to the principle of charity test, we should always interpret an unclear argument or passage as generously as possible. We could interpret Sam's argument as deductive. But this would be uncharitable, since the conclusion clearly doesn't follow from the premises with strict logical necessity. (It is logically possible--although highly unlikely--that a 90 -year-old woman who walks with a cane could climb Mt. Everest. ) Thus, the principle of charity test tells us to treat the argument as inductive.

Tess: Are there any good Italian restaurants in town? Don: Yeah, Luigi's is pretty good. I've had their Neapolitan rigatoni, their lasagne col pesto, and their mushroom ravioli. I don't think you can go wrong with any of their pasta dishes. Based on what you've learned in this Chapter , is this argument deductive or inductive? How can you tell?

Don: Yeah, Luigi's is pretty good. I've had their Neapolitan rigatoni, their lasagne col pesto, and their mushroom ravioli. I don't think you can go wrong with any of their pasta dishes. Inductive. The argument is an inductive generalization, which is a common pattern of inductive reasoning. Also, the conclusion does not follow with strict necessity from the premises.

I wonder if I have enough cash to buy my psychology textbook as well as my biology and history textbooks. Let's see, I have $200. My biology textbook costs $65 and my history textbook costs $52. My psychology textbook costs $60. With taxes, that should come to about $190. Yep, I have enough. Is this argument deductive or inductive? How can you tell?

I wonder if I have enough cash to buy my psychology textbook as well as my biology and history textbooks. Let's see, I have $200. My biology textbook costs $65 and my history textbook costs $52. My psychology textbook costs $60. With taxes, that should come to about $190. Yep, I have enough. Deductive. This argument is an argument based on mathematics, which is a common pattern of deductive reasoning. Plus, the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises.

Mother: Don't give Billy that brownie. It contains walnuts, and I think Billy is allergic to walnuts. Last week he ate some oatmeal cookies with walnuts and he broke out in a severe rash. Father: Billy isn't allergic to walnuts. Don't you remember he ate some walnut fudge ice cream at Melissa's birthday party last spring? He didn't have any allergic reaction then. Is the father's argument deductive or inductive? How can you tell?

Mother: Don't give Billy that brownie. It contains walnuts, and I think Billy is allergic to walnuts. Last week he ate some oatmeal cookies with walnuts, and he broke out in a severe rash. Father: Billy isn't allergic to walnuts. Don't you remember he ate some walnut fudge ice cream at Melissa's birthday party last spring? He didn't have any allergic reaction then. Inductive. The father's argument is a causal argument, which is a common pattern of inductive reasoning. Also, the conclusion does not follow necessarily from the premises. (Billy might have developed an allergic reaction to walnuts since last spring. )

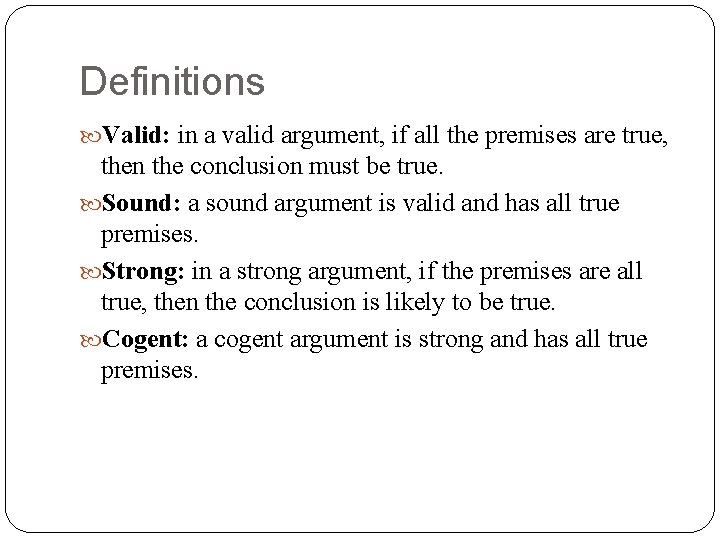

Definitions Valid: in a valid argument, if all the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true. Sound: a sound argument is valid and has all true premises. Strong: in a strong argument, if the premises are all true, then the conclusion is likely to be true. Cogent: a cogent argument is strong and has all true premises.

Argument Form • If the premises and the conclusion are statement forms instead of statements, then the resulting form is called argument form. • Ex: If p then q; p; q.

Validity of Argument Form Argument form is valid means that for any substitution of statement variables, if the premises are true, then the conclusion is also true. The example of previous slide is a valid argument form.

Checking the validity of an argument form Construct truth table for the premises and the conclusion; 2) Find the rows in which all the premises are true (critical rows); 3) a. If in each critical row the conclusion is true then the argument form is valid; b. If there is a row in which conclusion is false then the argument form is invalid. 1)

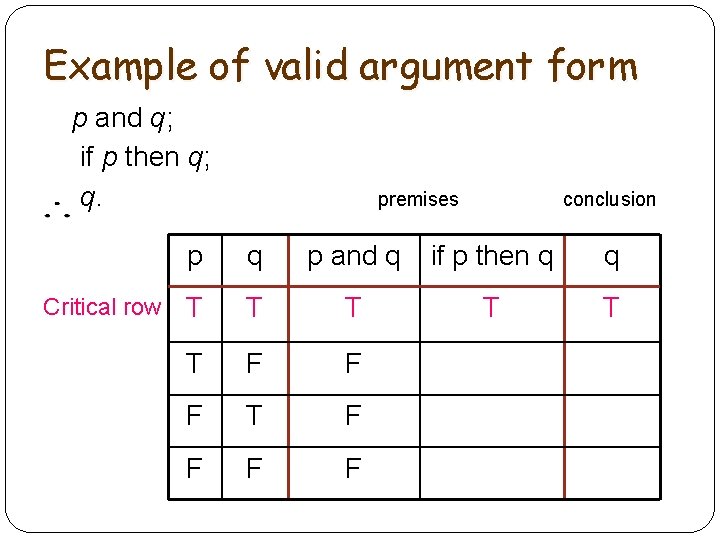

Example of valid argument form p and q; if p then q; q. Critical row premises conclusion p q p and q if p then q q T T T F F F T F F

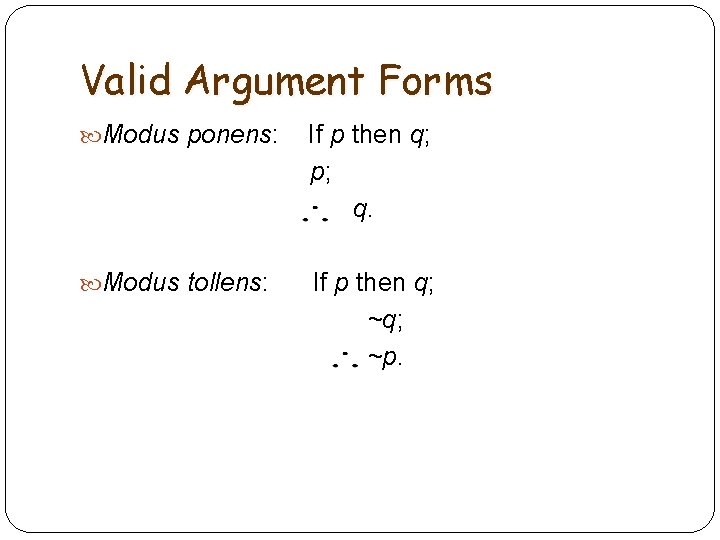

Valid Argument Forms Modus ponens: If p then q; p; q. Modus tollens: If p then q; ~p.

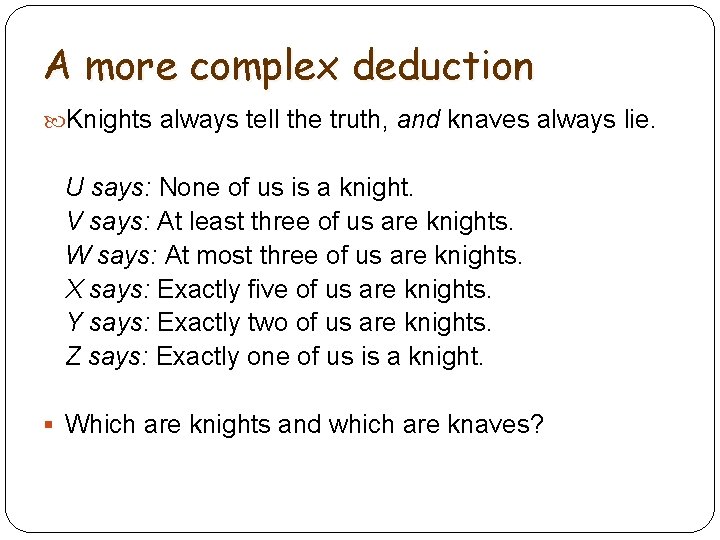

A more complex deduction Knights always tell the truth, and knaves always lie. U says: None of us is a knight. V says: At least three of us are knights. W says: At most three of us are knights. X says: Exactly five of us are knights. Y says: Exactly two of us are knights. Z says: Exactly one of us is a knight. § Which are knights and which are knaves?

- Slides: 27