Introduction to Clinical Trials Bias and the Need

Introduction to Clinical Trials - Bias and the Need for Randomized Studies Rick Chappell, Ph. D. Professor, Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics University of Wisconsin School of Medicine & Public Health chappell@stat. wisc. edu BMI 542 – Week 1, Lecture 1

Outline A. Types of clinical research studies B. Biases in clinical research studies C. Resources for writing protocols and reports of RCTs D. References

Good Ethics is Good Science: “If a research study is so methodologically flawed that little or no reliable information will result, it is unethical to put subjects at risk or even to inconvenience them through participation in such a study. … Clearly, if it is not good science, it is not ethical. ” - U. S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Policy for Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR 46, 1/1/92 ed. )

What is Good Science? The NIH (2016): Rigor ensures “… robust and unbiased experimental design, methodology, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of results. ” Reproducibility “… validates the original results”

What is Good Science? The NIH (2016): Rigor ensures “… robust and unbiased experimental design, methodology, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of results. ” Reproducibility “… validates the original results” Bias works against both attributes.

What is Good Science? The NIH (2016): Rigor ensures “… robust and unbiased experimental design, methodology, analysis, interpretation, and reporting of results. ” Reproducibility “… validates the original results” Bias works against both attributes. My definition of bias: “an error in estimation which doesn’t go away with large sample size. ”

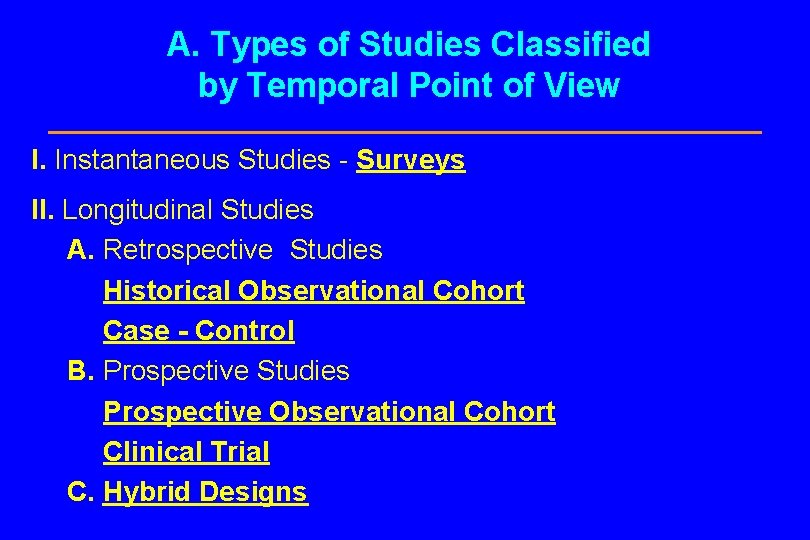

A. Types of Studies Classified by Temporal Point of View I. Instantaneous Studies - Surveys II. Longitudinal Studies A. Retrospective Studies Historical Observational Cohort Case - Control B. Prospective Studies Prospective Observational Cohort Clinical Trial C. Hybrid Designs

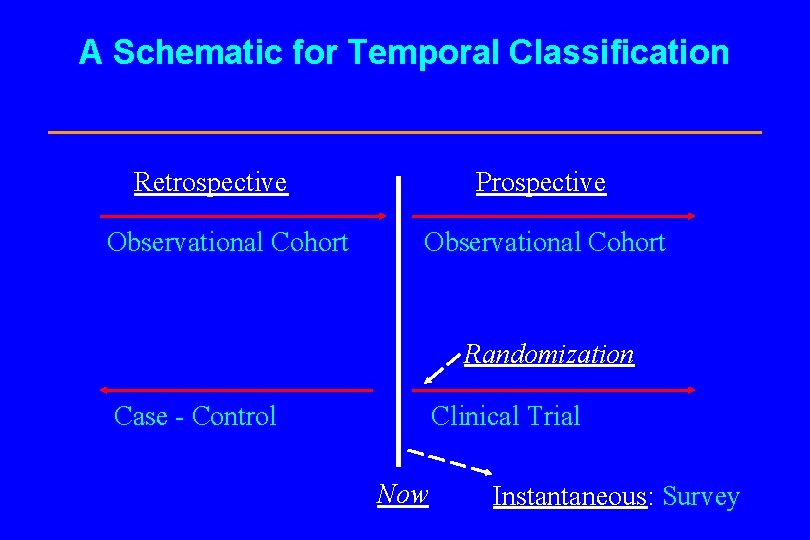

A Schematic for Temporal Classification Retrospective Observational Cohort Prospective Observational Cohort Randomization Case - Control Clinical Trial Now Instantaneous: Survey

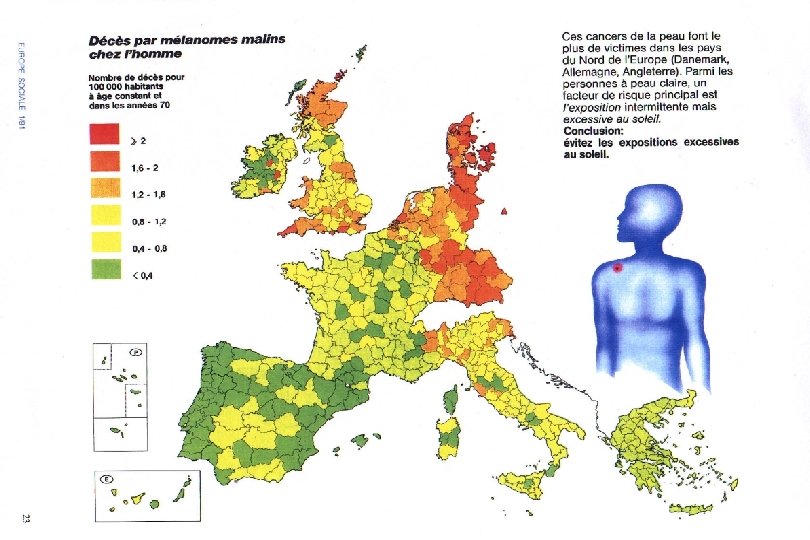

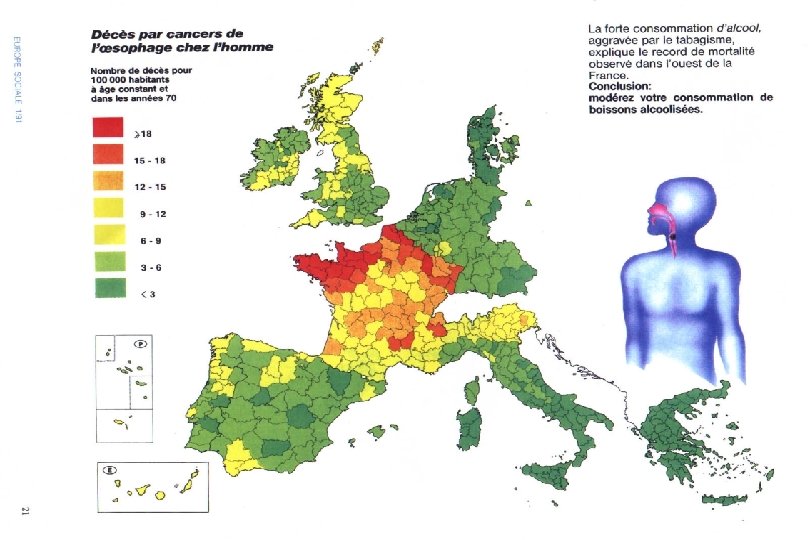

I. Instantaneous: Population-Based Studies l Synonyms n Survey n Population-Correlation Study n Ecological Study l Two or more populations are instantaneously compared through the prevalences of both exposure and disease.

Population-Based Studies Advantages Disadvantages l Instantaneous. l Intervention is usually not feasible. l Easy access to a large and varied population. l Very little information on causality: IARC standards require individual-based evidence. l Good for hypothesis generation.

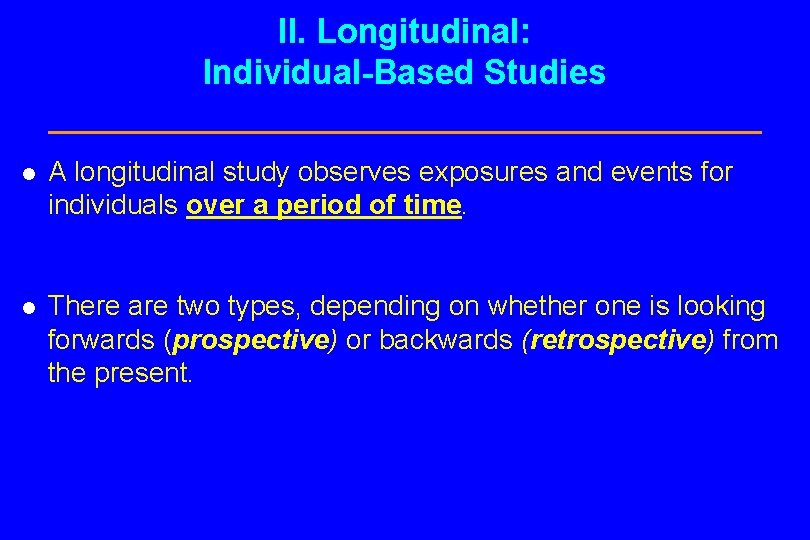

II. Longitudinal: Individual-Based Studies l A longitudinal study observes exposures and events for individuals over a period of time. l There are two types, depending on whether one is looking forwards (prospective) or backwards (retrospective) from the present.

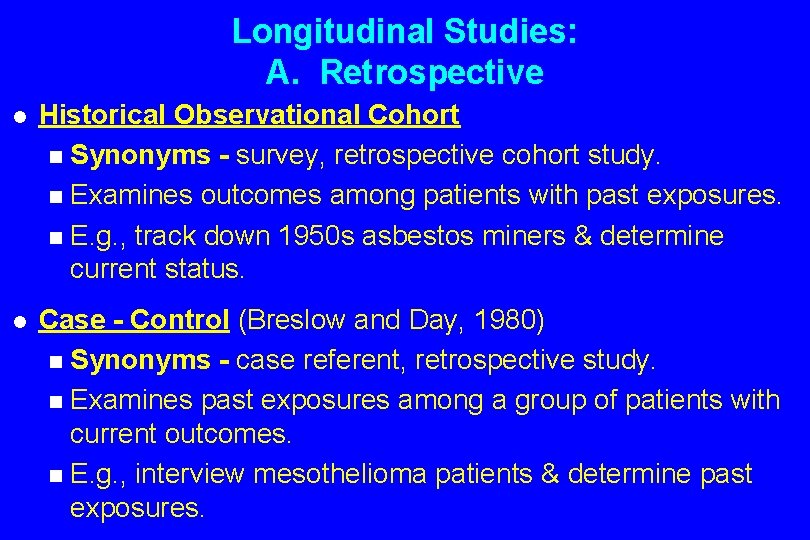

Longitudinal Studies: A. Retrospective l Historical Observational Cohort n Synonyms - survey, retrospective cohort study. n Examines outcomes among patients with past exposures. n E. g. , track down 1950 s asbestos miners & determine current status. l Case - Control (Breslow and Day, 1980) n Synonyms - case referent, retrospective study. n Examines past exposures among a group of patients with current outcomes. n E. g. , interview mesothelioma patients & determine past exposures.

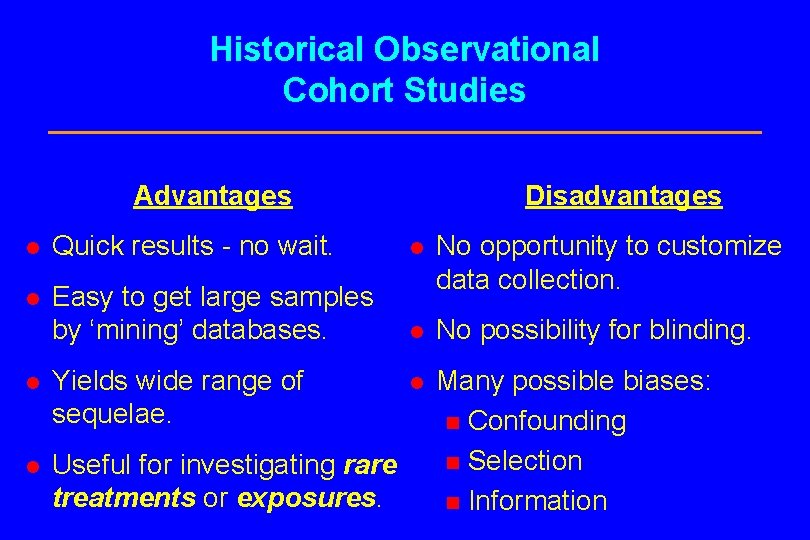

Historical Observational Cohort Studies Advantages Disadvantages l Quick results - no wait. l l Easy to get large samples by ‘mining’ databases. No opportunity to customize data collection. l No possibility for blinding. l Many possible biases: n Confounding n Selection n Information l Yields wide range of sequelae. l Useful for investigating rare treatments or exposures.

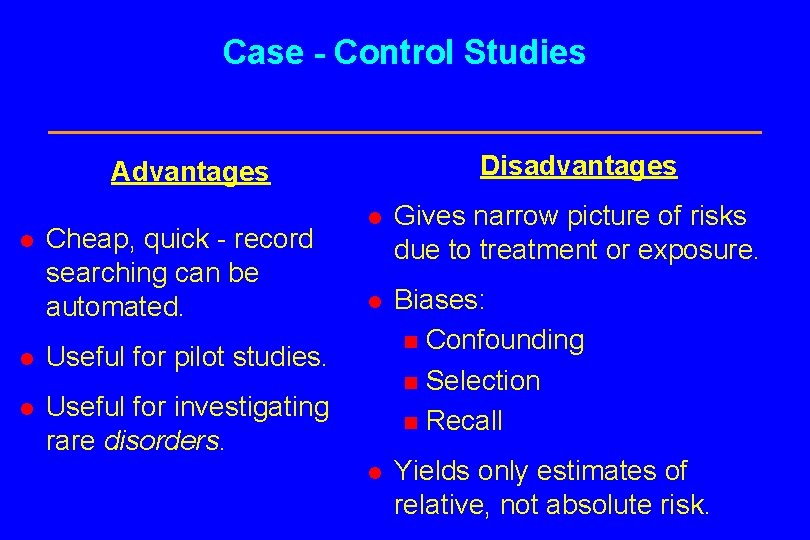

Case - Control Studies Disadvantages Advantages l Cheap, quick - record searching can be automated. l Useful for pilot studies. l Useful for investigating rare disorders. l Gives narrow picture of risks due to treatment or exposure. l Biases: n Confounding n Selection n Recall l Yields only estimates of relative, not absolute risk.

Longitudinal Studies: B. Prospective l General Advantages n Can collect detailed exposure, treatment, disease, and demographic information. n Blinding is possible. n Recall and information bias may be eliminated. n Useful for investigating rare treatments or exposures. l Classification depends on the presence of intervention.

Prospective Studies l Prospective Observational Cohort n Synonyms - prospective trial, ‘clinical trial’. n No intervention. l Randomized Controlled (“Phase III”) Clinical Trial n Synonyms - prospective interventional cohort study, experiment, prospective trial, clinical trial. n Experimenters directly intervene in patient treatment, usually on a randomized basis with controls.

Prospective Observational Cohort Study Additional Disadvantages Advantage l Passive observation; no need to dictate treatment. l May take a long time to accrue cases and wait for results. l Potential confounding bias due to lack of randomization and suitable controls.

Phases of a “Clinical Trial” l Biochemical and pharmacological research. l Animal Studies (Gart, 1986 & Schneiderman, 1967). l Phase I (Storer, 1989) - estimate toxicity rates using few (~ 10 - 40) healthy or sick subjects. l Phase II (Thall & Simon, 1995) - determines whether a therapy has potential using a few very sick patients.

Phases of a Clinical Trial (cont. ) l Phase III - large randomized controlled, possibly blinded, experiments; Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT). l Phase IV - a controlled trial of an approved treatment with long-term followup of safety and efficacy.

Clinical Trials Additional Advantages Disadvantages “The most definitive tool for evaluation of the applicability of clinical research” - 1979 NIH release. l As above, may take a long time. l Must be ethically and laboriously conducted. l Biases may be eliminated. l l Good design may make analysis simple. Requires treatment on basis (in part) of scientific rather than medical factors. Patients may make some sacrifice (Meier, 1982). l

Digression - NIH Organizational Structure, a Brief Overview (1) 1. Project Office/Funding Agency n Responsible for providing organizational, scientific & statistical direction through Project Officer n Contract Officer is responsible for all administrative matters related to award and conduct of contracts n Responsible for most of the pre-award development; RFP, sample size, etc. 2. Policy Advisory Board (PAB) Data Monitoring Board (DMB) n Acts as senior independent advisory board to NIH on policy matters n Reviews study design and changes to the initial design n Reviews interim study results, by treatment group and recommends early termination for toxicity or beneficial effects n Reviews performance of individual clinical centers

NIH Organizational Structure A Brief Overview (2) 3. Steering Committee n Provides scientific direction for the study at the operational level n Usually are recommended or elected representatives of the clinical center principle investigators n Monitors performance of individual centers n Report major problems to PAB and P. O. n May have several subcommittees which are responsible for various aspects such as recruitment, endpoints, publications, quality control, etc. 4. Assembly of Investigators (may be same as Steering Committee) n Each operational unit (clinic, laboratory, data center) has a representative n Elects from its membership representative on Steering Committee n Reviews operational progress of study n Represents individual clinical centers

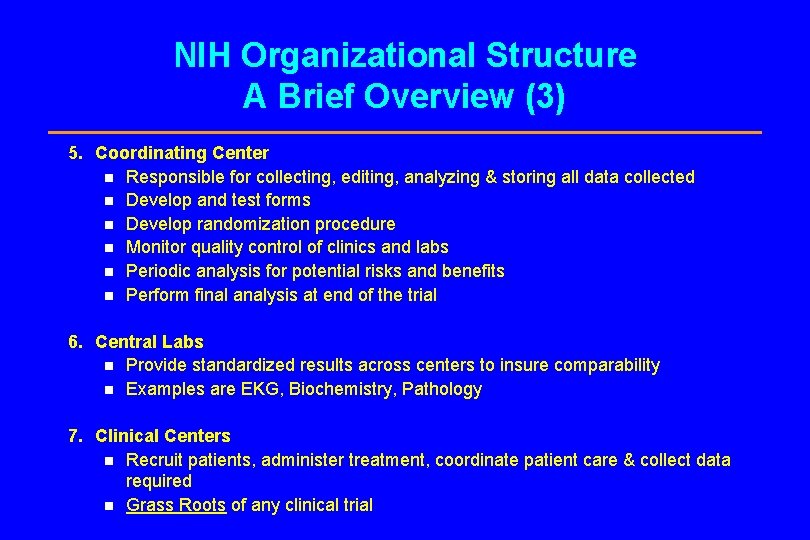

NIH Organizational Structure A Brief Overview (3) 5. Coordinating Center n Responsible for collecting, editing, analyzing & storing all data collected n Develop and test forms n Develop randomization procedure n Monitor quality control of clinics and labs n Periodic analysis for potential risks and benefits n Perform final analysis at end of the trial 6. Central Labs n Provide standardized results across centers to insure comparability n Examples are EKG, Biochemistry, Pathology 7. Clinical Centers n Recruit patients, administer treatment, coordinate patient care & collect data required n Grass Roots of any clinical trial

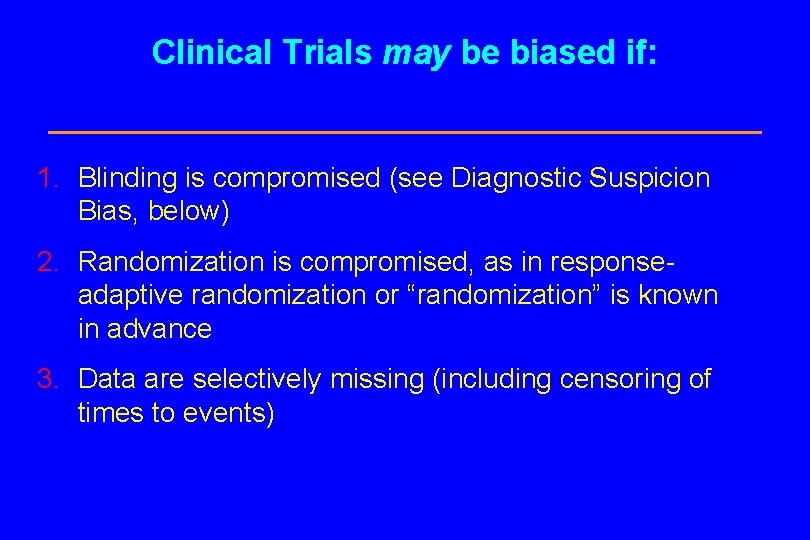

Clinical Trials may be biased if: 1. Blinding is compromised (see Diagnostic Suspicion Bias, below) 2. Randomization is compromised, as in responseadaptive randomization or “randomization” is known in advance 3. Data are selectively missing (including censoring of times to events)

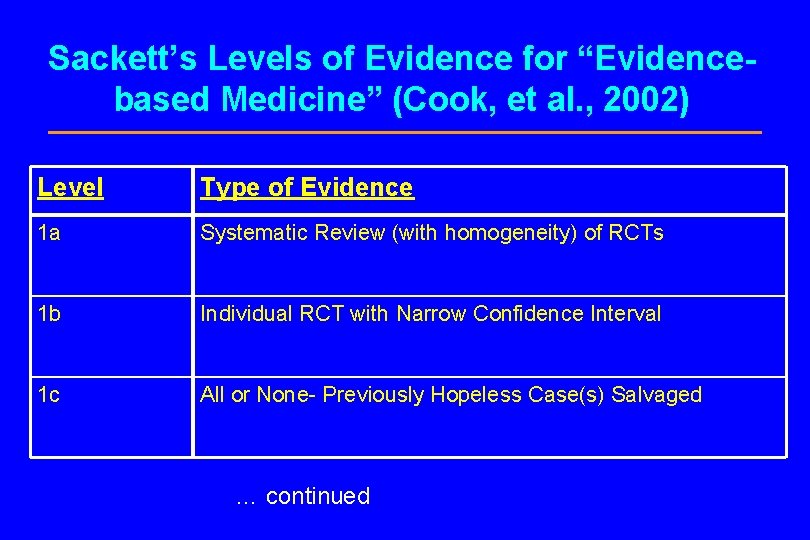

Sackett’s Levels of Evidence for “Evidencebased Medicine” (Cook, et al. , 2002) Level Type of Evidence 1 a Systematic Review (with homogeneity) of RCTs 1 b Individual RCT with Narrow Confidence Interval 1 c All or None- Previously Hopeless Case(s) Salvaged … continued

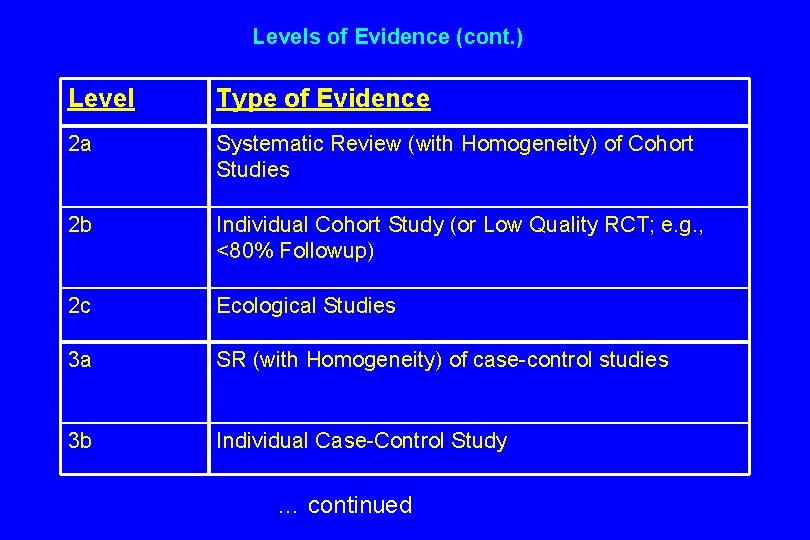

Levels of Evidence (cont. ) Level Type of Evidence 2 a Systematic Review (with Homogeneity) of Cohort Studies 2 b Individual Cohort Study (or Low Quality RCT; e. g. , <80% Followup) 2 c Ecological Studies 3 a SR (with Homogeneity) of case-control studies 3 b Individual Case-Control Study … continued

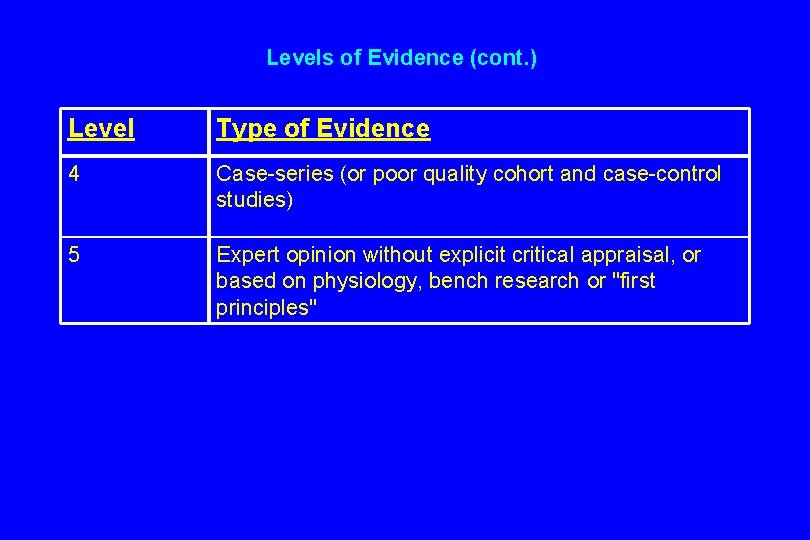

Levels of Evidence (cont. ) Level Type of Evidence 4 Case-series (or poor quality cohort and case-control studies) 5 Expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, or based on physiology, bench research or "first principles"

A critique (by example) of clinical trials and evidence-based medicine “Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials” (Smith & Pell, 2003). Fig. 1:

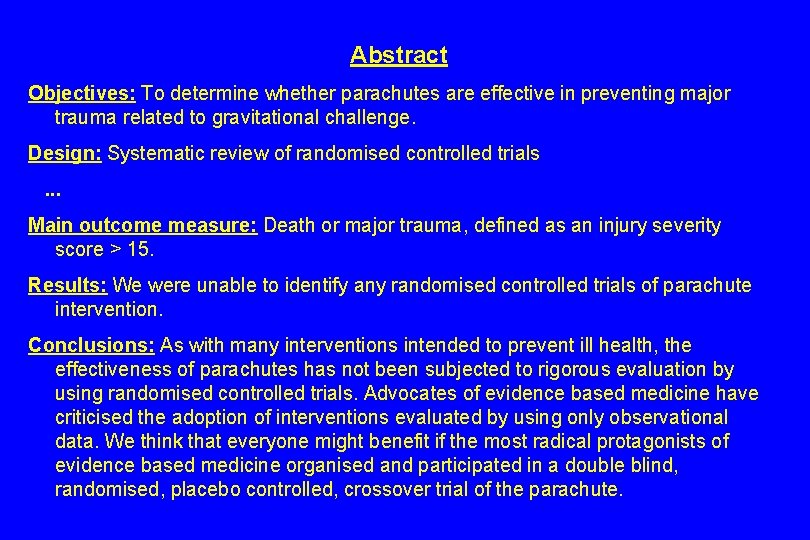

Abstract Objectives: To determine whether parachutes are effective in preventing major trauma related to gravitational challenge. Design: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials . . . Main outcome measure: Death or major trauma, defined as an injury severity score > 15. Results: We were unable to identify any randomised controlled trials of parachute intervention. Conclusions: As with many interventions intended to prevent ill health, the effectiveness of parachutes has not been subjected to rigorous evaluation by using randomised controlled trials. Advocates of evidence based medicine have criticised the adoption of interventions evaluated by using only observational data. We think that everyone might benefit if the most radical protagonists of evidence based medicine organised and participated in a double blind, randomised, placebo controlled, crossover trial of the parachute.

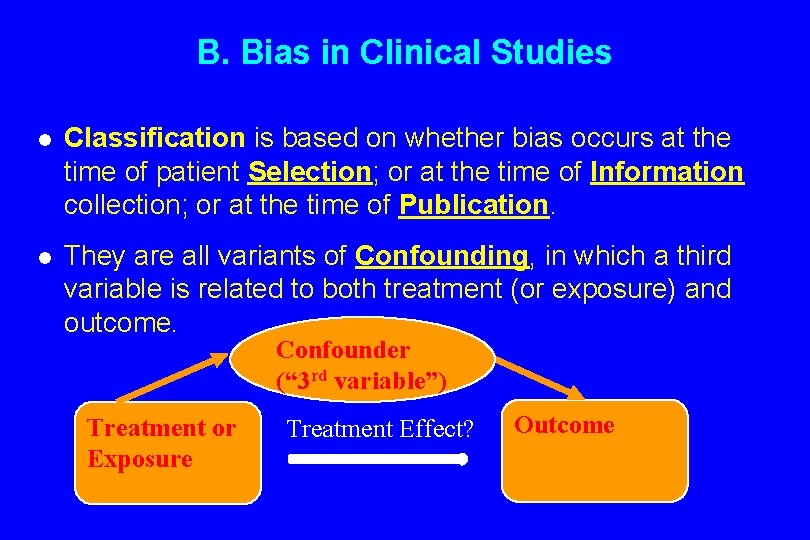

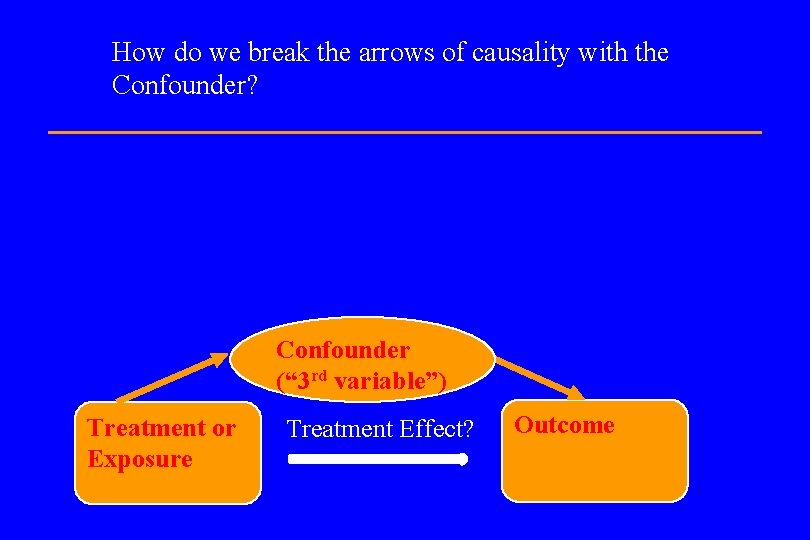

B. Bias in Clinical Studies l Classification is based on whether bias occurs at the time of patient Selection; or at the time of Information collection; or at the time of Publication. l They are all variants of Confounding, in which a third variable is related to both treatment (or exposure) and outcome. Confounder (“ 3 rd variable”) Treatment or Exposure Treatment Effect? Outcome

How do we break the arrows of causality with the Confounder? Confounder (“ 3 rd variable”) Treatment or Exposure Treatment Effect? Outcome

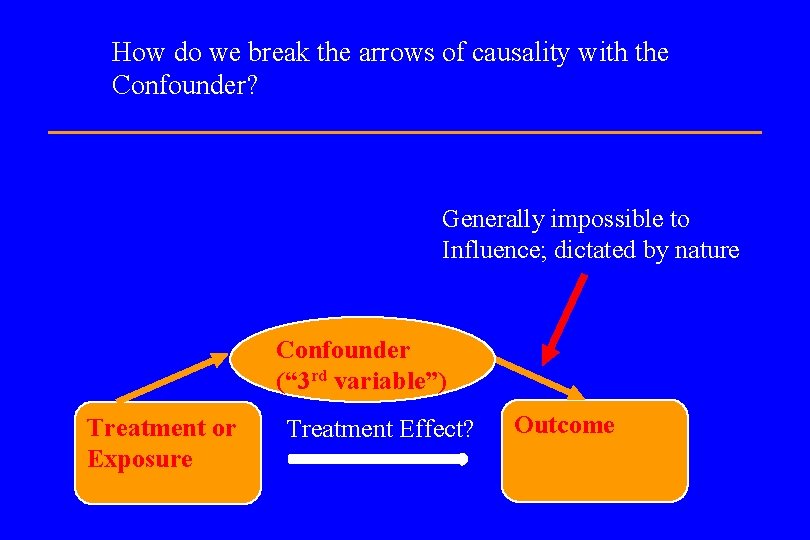

How do we break the arrows of causality with the Confounder? Generally impossible to Influence; dictated by nature Confounder (“ 3 rd variable”) Treatment or Exposure Treatment Effect? Outcome

How do we break the arrows of causality with the Confounder? Can be broken via randomization Generally impossible to influence; dictated by nature Confounder (“ 3 rd variable”) Treatment or Exposure Treatment Effect? Outcome

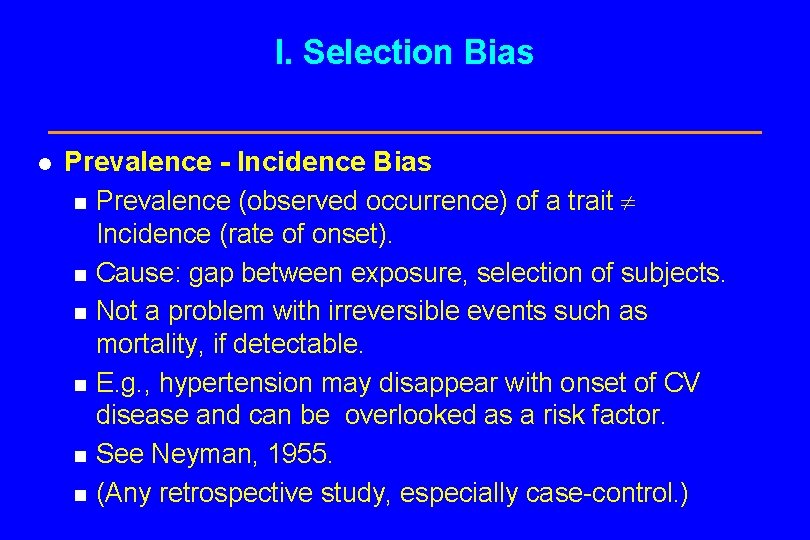

I. Selection Bias l Prevalence - Incidence Bias n Prevalence (observed occurrence) of a trait Incidence (rate of onset). n Cause: gap between exposure, selection of subjects. n Not a problem with irreversible events such as mortality, if detectable. n E. g. , hypertension may disappear with onset of CV disease and can be overlooked as a risk factor. n See Neyman, 1955. n (Any retrospective study, especially case-control. )

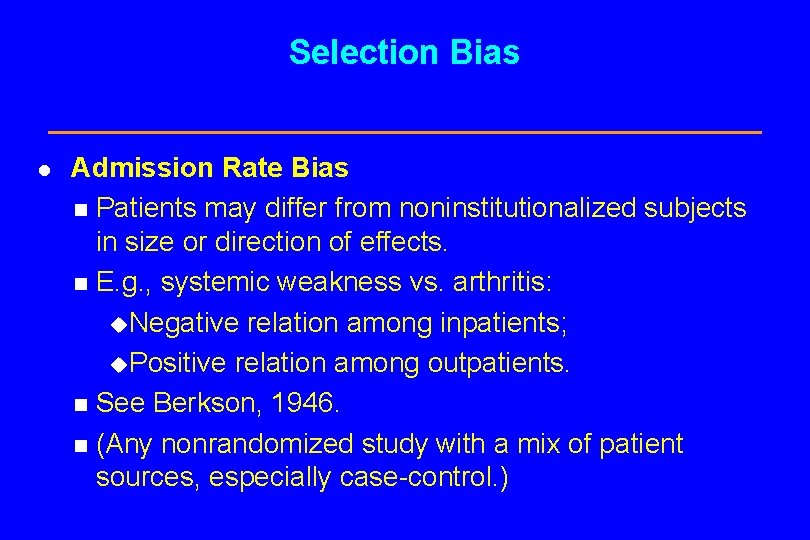

Selection Bias l Admission Rate Bias Patients may differ from noninstitutionalized subjects in size or direction of effects. n E. g. , systemic weakness vs. arthritis: u. Negative relation among inpatients; u. Positive relation among outpatients. n See Berkson, 1946. n (Any nonrandomized study with a mix of patient sources, especially case-control. ) n

Selection Bias l Nonrespondant (Volunteer) Bias n Nonparticipation may be related to the subject of investigation. n E. g. , smokers ignore surveys more often than do nonsmokers (Seltzer, 1974). n For general methods to analyze data with ‘nonignorable nonresponse’ see Little and Rubin (1987). n (Case-control, though drop-outs can effect any study not analyzed ‘intent to treat. )

Example: Where to add armor to fighter planes? In World War II the U. S. Air Force conducted an investigation into where armor could most effectively be added to fighter planes. Researchers examined returning aircraft, mapped the locations of bullet holes, and recommended that the most commonly pierced areas be reinforced.

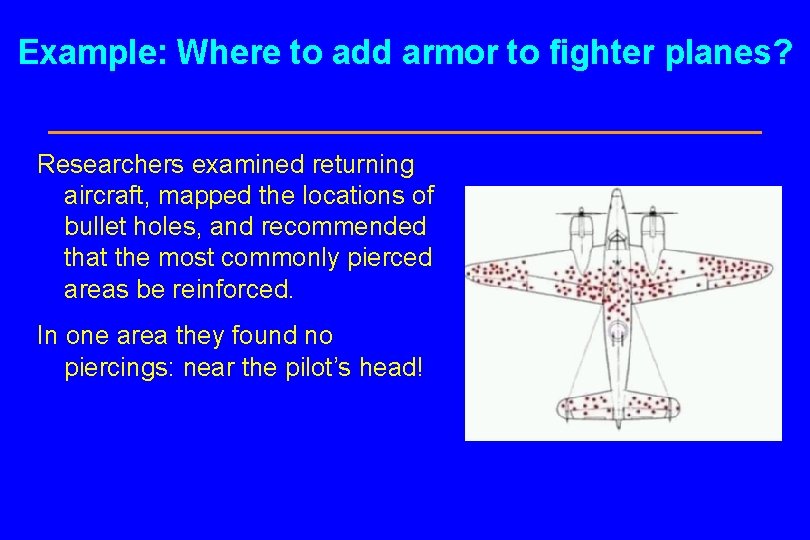

Example: Where to add armor to fighter planes? Researchers examined returning aircraft, mapped the locations of bullet holes, and recommended that the most commonly pierced areas be reinforced. In one area they found no piercings: near the pilot’s head!

II. Information Bias l Detection Signal (Diagnostic Suspicion) Bias n In unblinded studies, an exposure may be considered a risk factor for an endpoint, and such patients preferentially observed. n In blinded studies, an exposure may make an endpoint more detectable. n E. g. , estrogen causes bleeding from uterine cancer to be more easily detectable. n (Any unblinded study except case-control; also even blinded clinical trials with sensitive endpoints. )

II. Information Bias l Detection Signal (Diagnostic Suspicion) Bias n In unblinded studies, an exposure may be considered a risk factor for an endpoint, and such patients preferentially observed. n In blinded studies, an exposure may make an endpoint more detectable. n E. g. , estrogen causes bleeding from uterine cancer to be more easily detectable. n (Any unblinded study except case-control; also even blinded clinical trials with sensitive endpoints. )

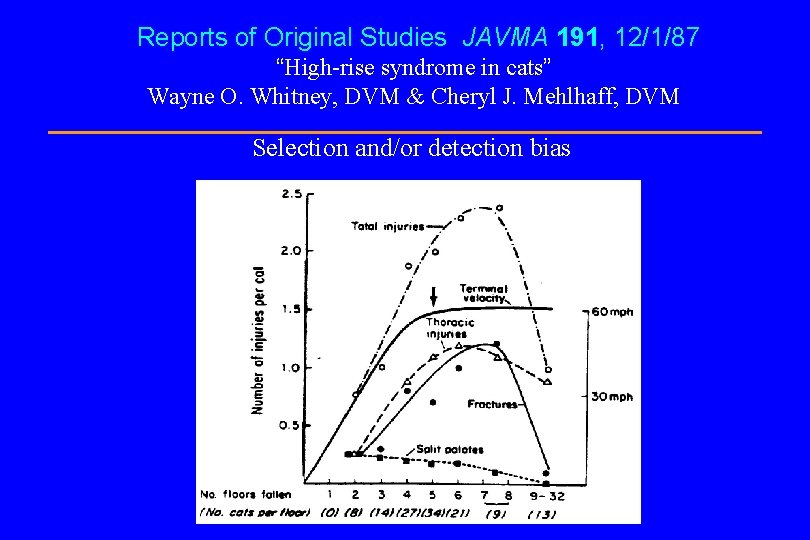

Reports of Original Studies JAVMA 191, 12/1/87 “High-rise syndrome in cats” Wayne O. Whitney, DVM & Cheryl J. Mehlhaff, DVM Selection and/or detection bias

Information Bias l Exposure Suspicion Bias n An outcome may cause the investigator to look for a particular exposure. n The temporal reverse of detection signal bias. n E. g. , arthritis and knuckle-cracking. n (Case-control studies. )

Information Bias l Recall (family information) Bias n Similar to exposure suspicion bias, but errors originate with the subject or his/her family. n E. g. , in a study of prescription use among women with fetal malformation, 28% reported unverifiable exposure vs. 20% of the controls (Klemetti & Saxen, 1967). n (Case-control studies. )

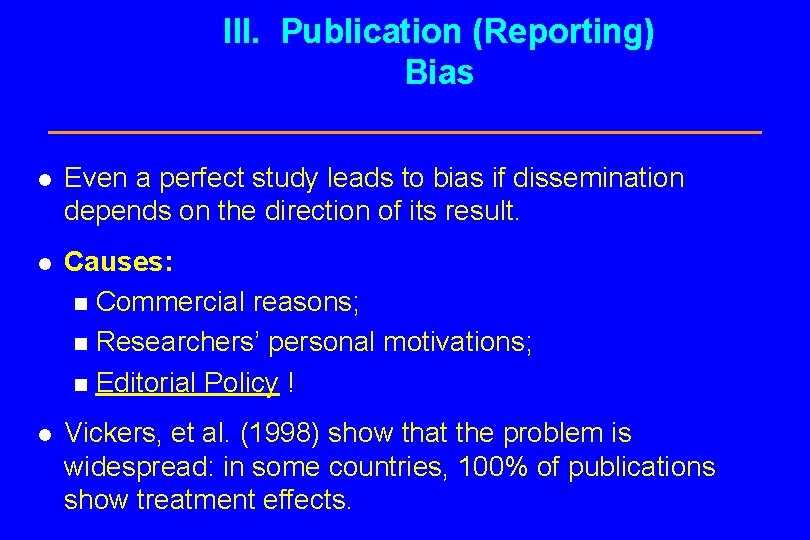

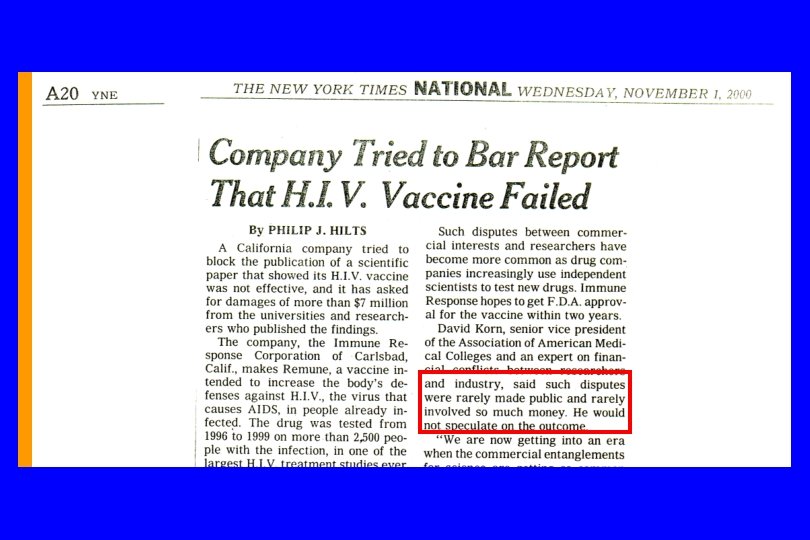

III. Publication (Reporting) Bias l Even a perfect study leads to bias if dissemination depends on the direction of its result. l Causes: n Commercial reasons; n Researchers’ personal motivations; n Editorial Policy ! l Vickers, et al. (1998) show that the problem is widespread: in some countries, 100% of publications show treatment effects.

Publication (Reporting) Bias l A version of the multiple comparisons problem (Miller, 1985), or ‘testing to a foregone conclusion’. l E. g. , ORG-2766 protected nerves from cytotoxic injury in 55 women with ovarian cancer - NEJM lead article (van der Hoop, et al. , 1990); a subsequent negative study of 133 women - ASCO Proceedings abstract (Neijt, et al. , 1994). l (All Studies. )

Publication (Reporting) Bias Thus, the NIH’s demand: “Consideration of refutations Have a policy stating that if the journal publishes a paper, it assumes responsibility to consider publication of refutations of that paper, according to its usual standards of quality. ”

Solutions to Publication Bias 1. Register trials (before they start) with the Cochrane Collaboration – www. cochrane. org "We gather and summarize the best evidence from research to help you make informed choices about treatment" via systematic reviews (meta-analyses) 2. Register trials (ditto) with www. clintrials. gov 3. Take “The trialist’s oath” (Meinert) - https: //jhuccs 1. us/clm/PDFs/OATH. pdf

The trialist's oath (Meinert) Whereas: Being able to research on human beings is a privilege granted only by an accepting society, and whereas Research is done to advance knowledge, and whereas There is no advance of knowledge in the societal sense without publication.

Therefore, as a trialist, I am obliged to: l Ensure the trial I participate in is registered and that the registration is updated as the trial proceeds. l Ensure existence of a statement fashioned and approved by study investigators committing to publication when the trial is finished or stopped because of benefit or harm. l Make every effort to publish results of the trial when finished or stopped without regard to the nature or direction of results. … l Publish in peer-reviewed, indexed, medical journals. l Resist efforts by others to acquire study data until investigators have published or until they have abandoned efforts to publish after repeated rejections of the results manuscript.

NEWS RELEASE 17 -JAN-2020 The Lancet: Fewer than half of US clinical trials have complied with the law on reporting results, despite new regulations January 2020 is the third anniversary of the implementation of the new US regulations that require clinical trials to report results within one year of completion (Final Rule of the FDA Amendments Act)--but compliance remains poor, and is not improving, with US Government sponsored trials most likely to breach. Less than half (41%) of clinical trial results are reported promptly onto the US trial registry, and 1 in 3 trials remain unreported, according to the first comprehensive study of compliance since new US regulations came into effect in January 2017.

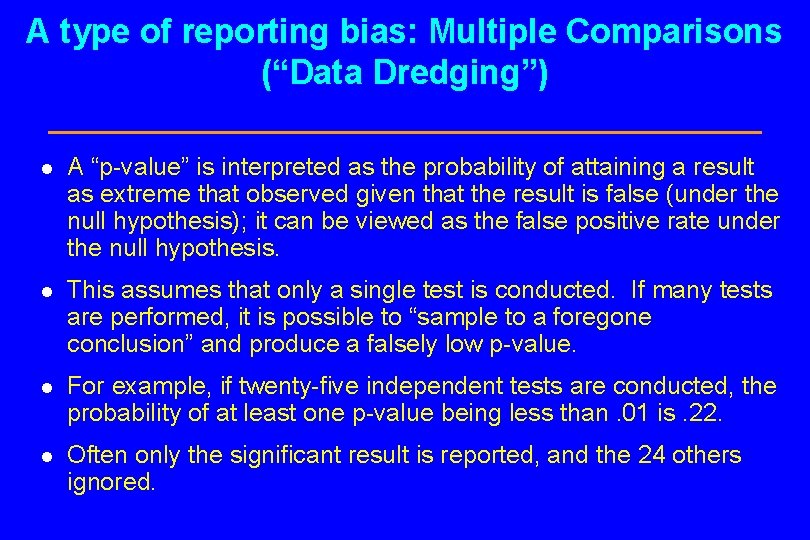

A type of reporting bias: Multiple Comparisons (“Data Dredging”) l A “p-value” is interpreted as the probability of attaining a result as extreme that observed given that the result is false (under the null hypothesis); it can be viewed as the false positive rate under the null hypothesis. l This assumes that only a single test is conducted. If many tests are performed, it is possible to “sample to a foregone conclusion” and produce a falsely low p-value. l For example, if twenty-five independent tests are conducted, the probability of at least one p-value being less than. 01 is. 22. l Often only the significant result is reported, and the 24 others ignored.

IV. Confounding (General Examples) l Caused by any situation in which: n A third variable exists which isn’t known or at least isn’t accounted for; n It is associated with the “cause” and n It is also associated with the “effect”. Then: l The supposed cause-effect relation will be confounded by the third variable. l (Any nonrandomized study)

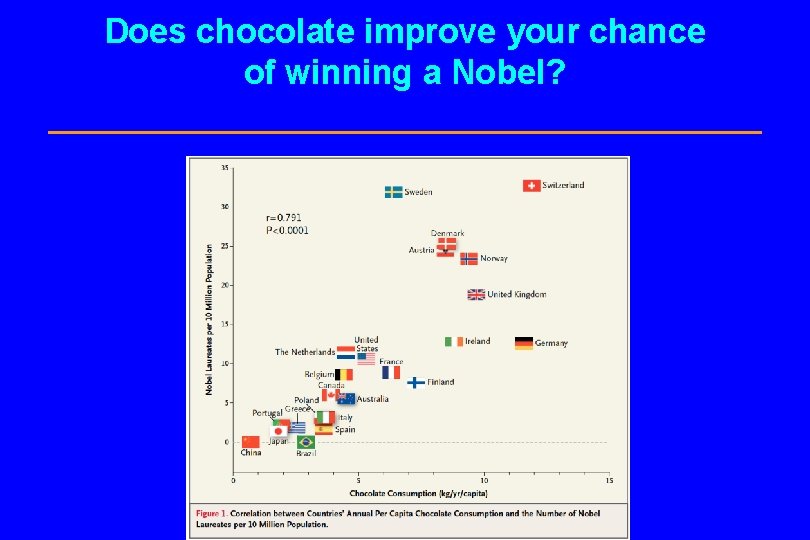

Does chocolate improve your chance of winning a Nobel?

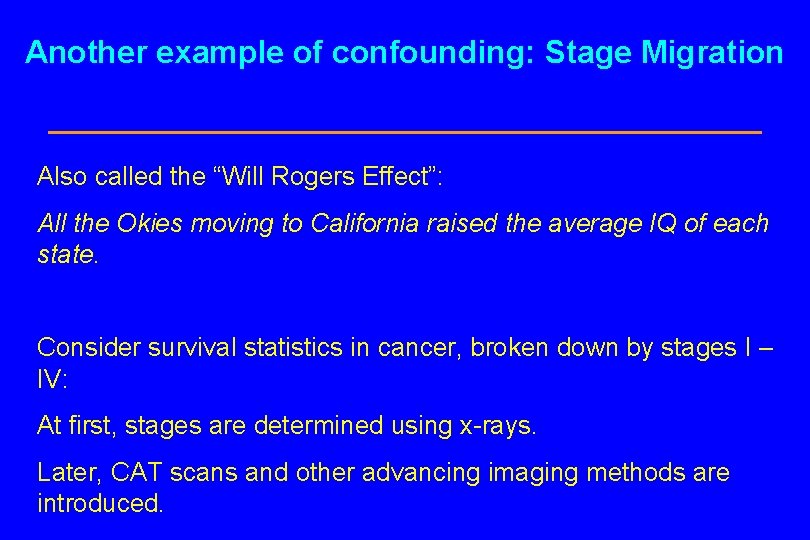

Another example of confounding: Stage Migration Also called the “Will Rogers Effect”: All the Okies moving to California raised the average IQ of each state. Consider survival statistics in cancer, broken down by stages I – IV: At first, stages are determined using x-rays. Later, CAT scans and other advancing imaging methods are introduced.

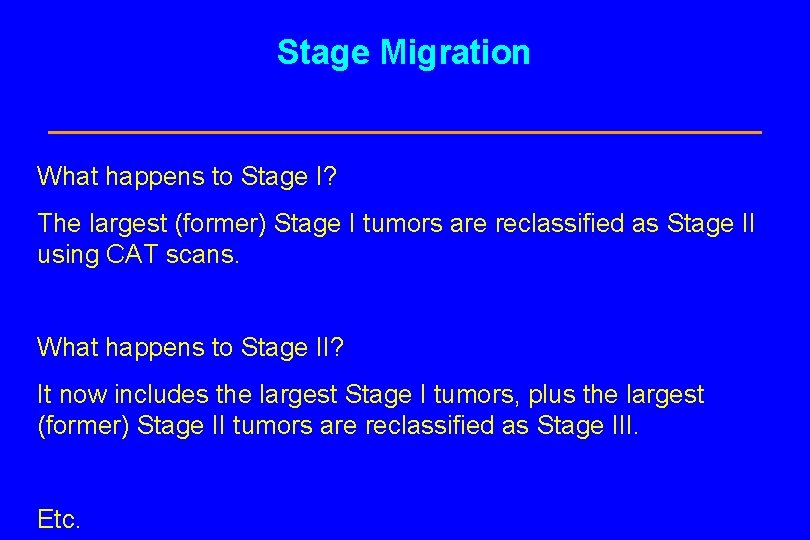

Stage Migration What happens to Stage I? The largest (former) Stage I tumors are reclassified as Stage II using CAT scans. What happens to Stage II? It now includes the largest Stage I tumors, plus the largest (former) Stage II tumors are reclassified as Stage III. Etc.

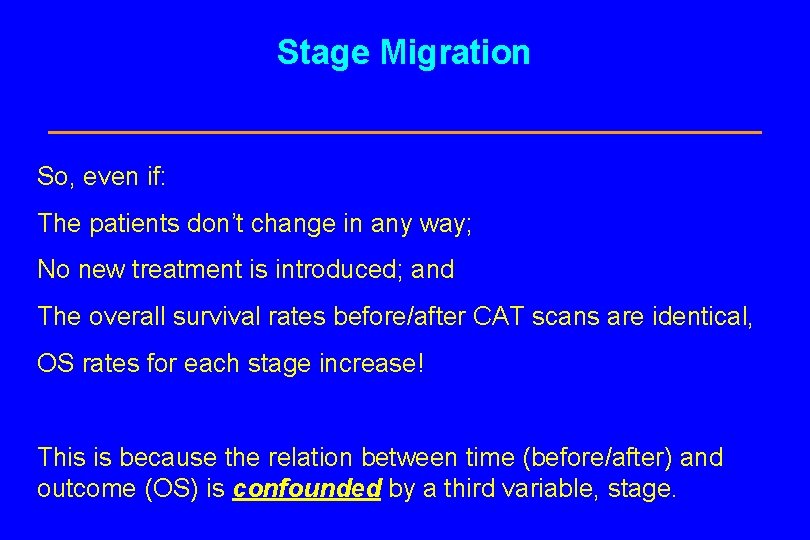

Stage Migration So, even if: The patients don’t change in any way; No new treatment is introduced; and The overall survival rates before/after CAT scans are identical, OS rates for each stage increase! This is because the relation between time (before/after) and outcome (OS) is confounded by a third variable, stage.

C. Some Useful References for Writing Clinical Trials Reports and Protocols 1. ICH Guideline E 3 (see Course reference list) 2. CONSORT statement (see Course reference list) 3. NIH Protocol Template: http: //osp. od. nih. gov/sites/default/files/Protocol_Template_05 Fe b 2016_508. pdf (or google “NIH Protocol Template”) 4. SPIRIT (Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials) statement: https: //www. spiritstatement. org/ Also see sample protocol NPC 9901 F. DOC in course website (Case Study #4)

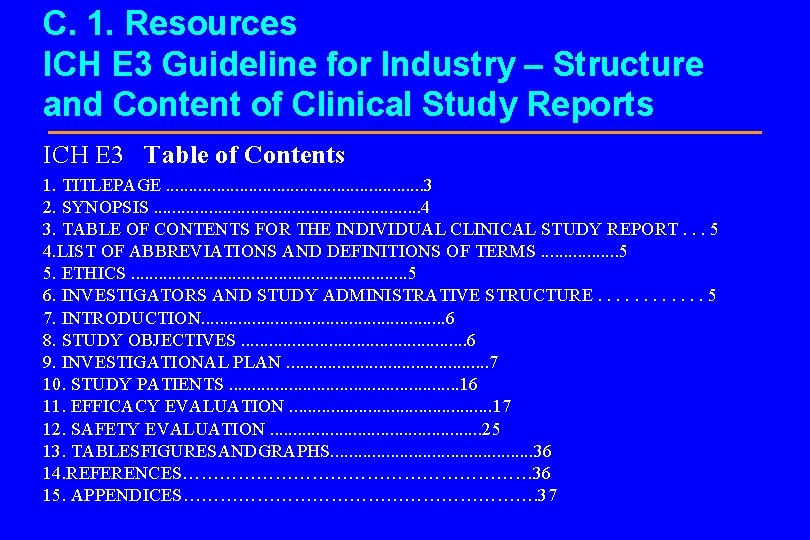

C. 1. Resources ICH E 3 Guideline for Industry – Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports ICH E 3 Table of Contents 1. TITLEPAGE. . . . 3 2. SYNOPSIS. . . . 4 3. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THE INDIVIDUAL CLINICAL STUDY REPORT. . . 5 4. LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND DEFINITIONS OF TERMS. . . . 5 5. ETHICS. . . . 5 6. INVESTIGATORS AND STUDY ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURE. . . 5 7. INTRODUCTION. . . . 6 8. STUDY OBJECTIVES. . . 6 9. INVESTIGATIONAL PLAN. . . 7 10. STUDY PATIENTS. . . 16 11. EFFICACY EVALUATION. . . 17 12. SAFETY EVALUATION. . . 25 13. TABLESFIGURESANDGRAPHS. . . 36 14. REFERENCES………………………… 36 15. APPENDICES…………………………. 37

C. 2. CONSORT NIH: Journals should use a checklist during editorial processing to ensure the reporting of key methodological and analytical information to reviewers and readers. The CONSORT statement: Updated Guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials (see course references). A concise guide to the necessary contents of a report for a RCT: three pages of text and one figure. Other CONSORT publications are available for reports of metaanalyses, quality of life studies, etc.

C. 3. Protocol Resources See NIH Template For a Specific Example (Course Website): PROSPECTIVE RANDOMIZED STUDY ON THERAPEUTIC GAIN ACHIEVED BY ADDITION OF CHEMOTHERAPY FOR T 1 -4 N 2 -3 M 0 NASOPHARYNGEAL CARCINOMA JOINTLY ORGANIZED BY THE HONG KONG NASOPHARYNGEAL CANCER STUDY GROUP AND PRINCESS MARGARET HOSPITAL OF CANADA FINAL PROTOCOL Trial Code: NPC 99 -01

Purposes of a Protocol 1. To assist the investigator in thinking through the research. 2. To insure that both patient and study management are considered at the planning stage. 3. To provide a “sounding board” for external comments. 4. To orient the staff for the preparation of forms and data processing procedures. 5. To guide the treatment of the patient on the study. 6. To provide a document which can be used by other investigators who wish to “confirm” the results or use the treatment in practice. Reference: Dana-Farber Cancer Institute: Outline to Writing a Protocol

Protocol Outline: “A Blueprint” (1) A. Background & Rationale B. Objectives 1. Primary Question 2. Secondary Question 3. Subgroup Questions 4. Toxicities

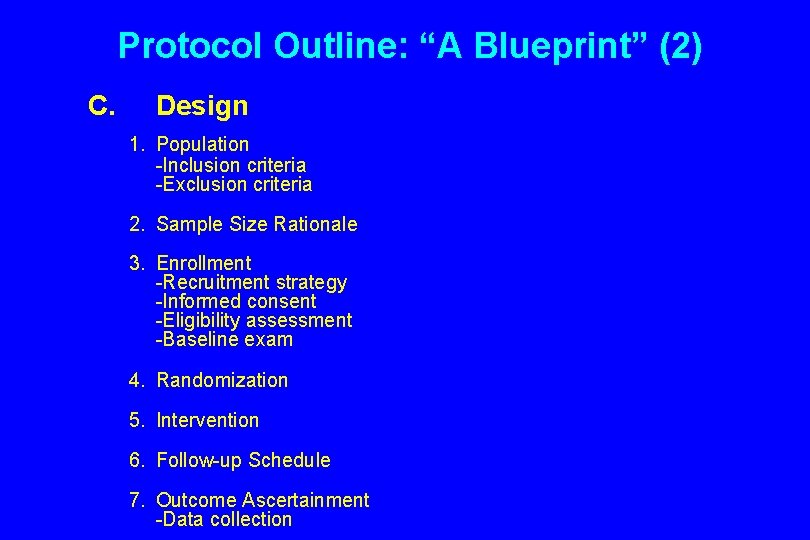

Protocol Outline: “A Blueprint” (2) C. Design 1. Population -Inclusion criteria -Exclusion criteria 2. Sample Size Rationale 3. Enrollment -Recruitment strategy -Informed consent -Eligibility assessment -Baseline exam 4. Randomization 5. Intervention 6. Follow-up Schedule 7. Outcome Ascertainment -Data collection

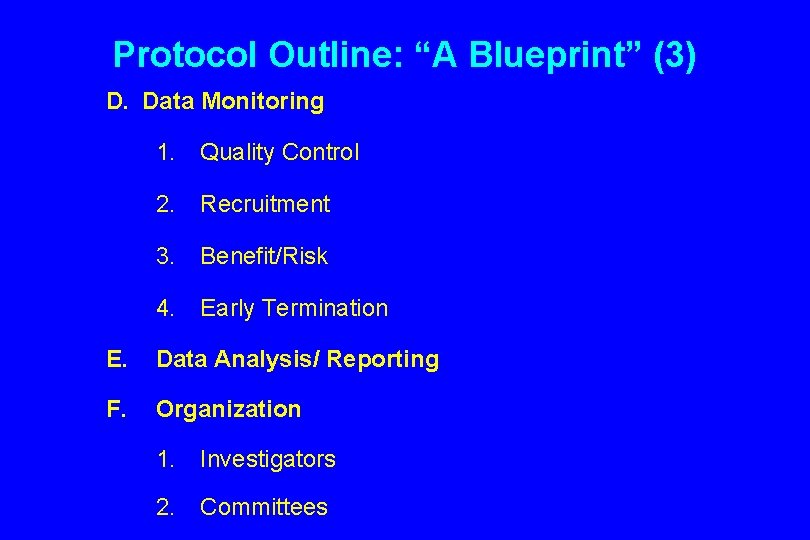

Protocol Outline: “A Blueprint” (3) D. Data Monitoring 1. Quality Control 2. Recruitment 3. Benefit/Risk 4. Early Termination E. Data Analysis/ Reporting F. Organization 1. Investigators 2. Committees

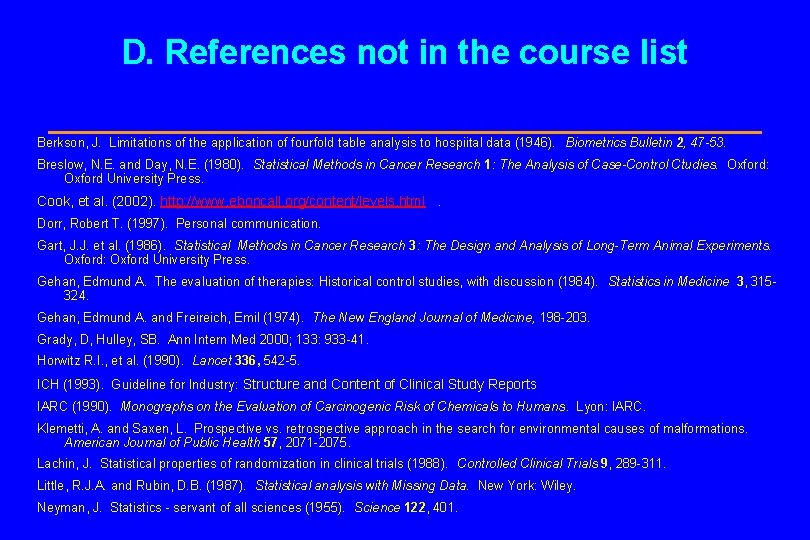

D. References not in the course list Berkson, J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospiital data (1946). Biometrics Bulletin 2, 47 -53. Breslow, N. E. and Day, N. E. (1980). Statistical Methods in Cancer Research 1: The Analysis of Case-Control Ctudies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cook, et al. (2002). http: //www. eboncall. org/content/levels. html . Dorr, Robert T. (1997). Personal communication. Gart, J. J. et al. (1986). Statistical Methods in Cancer Research 3: The Design and Analysis of Long-Term Animal Experiments. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gehan, Edmund A. The evaluation of therapies: Historical control studies, with discussion (1984). Statistics in Medicine 3, 315324. Gehan, Edmund A. and Freireich, Emil (1974). The New England Journal of Medicine, 198 -203. Grady, D, Hulley, SB. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 933 -41. Horwitz R. I. , et al. (1990). Lancet 336, 542 -5. ICH (1993). Guideline for Industry: Structure and Content of Clinical Study Reports IARC (1990). Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans. Lyon: IARC. Klemetti, A. and Saxen, L. Prospective vs. retrospective approach in the search for environmental causes of malformations. American Journal of Public Health 57, 2071 -2075. Lachin, J. Statistical properties of randomization in clinical trials (1988). Controlled Clinical Trials 9, 289 -311. Little, R. J. A. and Rubin, D. B. (1987). Statistical analysis with Missing Data. New York: Wiley. Neyman, J. Statistics - servant of all sciences (1955). Science 122, 401.

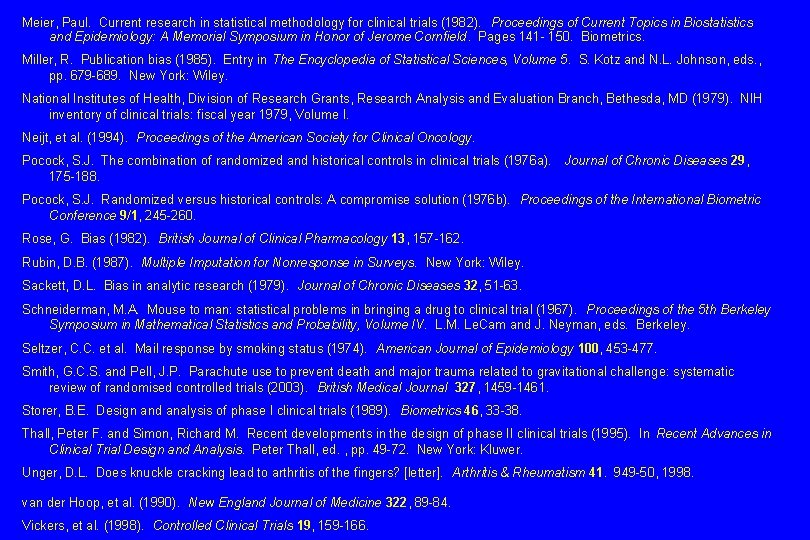

Meier, Paul. Current research in statistical methodology for clinical trials (1982). Proceedings of Current Topics in Biostatistics and Epidemiology: A Memorial Symposium in Honor of Jerome Cornfield. Pages 141 - 150. Biometrics. Miller, R. Publication bias (1985). Entry in The Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences, Volume 5. S. Kotz and N. L. Johnson, eds. , pp. 679 -689. New York: Wiley. National Institutes of Health, Division of Research Grants, Research Analysis and Evaluation Branch, Bethesda, MD (1979). NIH inventory of clinical trials: fiscal year 1979, Volume I. Neijt, et al. (1994). Proceedings of the American Society for Clinical Oncology. Pocock, S. J. The combination of randomized and historical controls in clinical trials (1976 a). Journal of Chronic Diseases 29, 175 -188. Pocock, S. J. Randomized versus historical controls: A compromise solution (1976 b). Proceedings of the International Biometric Conference 9/1, 245 -260. Rose, G. Bias (1982). British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 13, 157 -162. Rubin, D. B. (1987). Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley. Sackett, D. L. Bias in analytic research (1979). Journal of Chronic Diseases 32, 51 -63. Schneiderman, M. A. Mouse to man: statistical problems in bringing a drug to clinical trial (1967). Proceedings of the 5 th Berkeley Symposium in Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume IV. L. M. Le. Cam and J. Neyman, eds. Berkeley. Seltzer, C. C. et al. Mail response by smoking status (1974). American Journal of Epidemiology 100, 453 -477. Smith, G. C. S. and Pell, J. P. Parachute use to prevent death and major trauma related to gravitational challenge: systematic review of randomised controlled trials (2003). British Medical Journal 327, 1459 -1461. Storer, B. E. Design and analysis of phase I clinical trials (1989). Biometrics 46, 33 -38. Thall, Peter F. and Simon, Richard M. Recent developments in the design of phase II clinical trials (1995). In Recent Advances in Clinical Trial Design and Analysis. Peter Thall, ed. , pp. 49 -72. New York: Kluwer. Unger, D. L. Does knuckle cracking lead to arthritis of the fingers? [letter]. Arthritis & Rheumatism 41. 949 -50, 1998. van der Hoop, et al. (1990). New England Journal of Medicine 322, 89 -84. Vickers, et al. (1998). Controlled Clinical Trials 19, 159 -166.

- Slides: 73