Introduction to Abstract Interpretation Andy King a m

Introduction to Abstract Interpretation Andy King a. m. king@kent. ac. uk http: //www. cs. kent. ac. uk/~amk

Pointers to the literature z SAS, POPL, ESOP, ICLP, ICFP, … z Useful review articles and books: y. Patrick and Radhia Cousot, Comparing the Galois connection and Widening/Narrowing approaches to Abstract Interpretation, PLILP, LNCS 631, 269 -295, 1992. Available from LIX library. y. Patrick and Radhia Cousot, Abstract interpretation and Application to Logic Programs, JLP, 13(2 -3): 103 -179, 1992 y. Flemming Neilson, Hanne Riis Neilson and Chris Hankin, Principles of Program Analysis, Springer, 1999. y. Patrick has a database of abstract interpretation researchers and regularly writes tutorials, see, CC’ 02.

Applications of abstract interpretation z Verification: can a concurrent program deadlock? Is termination assured? z Parallelisation: are two or more tasks independent? What is the worst/best-case running time of function? z Transformation: can a definition be unfolded? Will unfolding terminate? z Implementation: can an operation be specialised with knowledge of its (global) calling context? z Applications and “players” are incredibly diverse

Casting out nines algorithm z Which of the following multiplications are correct: y 2173 38 = 81574 or y 2173 38 = 82574 z Casting out nines is a checking technique that is really a form of abstract interpretation: y. Sum the digits in the multiplicand n 1, multiplier n 2 and the product n to obtain s 1, s 2 and s. y. Divide s 1, s 2 and s by 9 to compute the remainder, that is, r 1 = s 1 mod 9, r 2 = s 2 mod 9 and r = s mod 9. y. Calculate r’ = (r 1 r 2) mod 9 y. If r’ r then multiplication is incorrect z The algorithm returns “incorrect” or “don’t know”

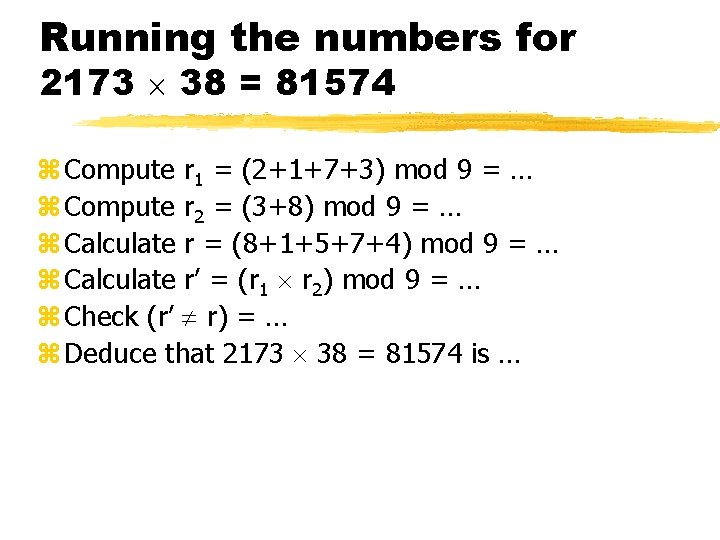

Running the numbers for 2173 38 = 81574 z Compute r 1 = (2+1+7+3) mod 9 = … z Compute r 2 = (3+8) mod 9 = … z Calculate r = (8+1+5+7+4) mod 9 = … z Calculate r’ = (r 1 r 2) mod 9 = … z Check (r’ r) = … z Deduce that 2173 38 = 81574 is …

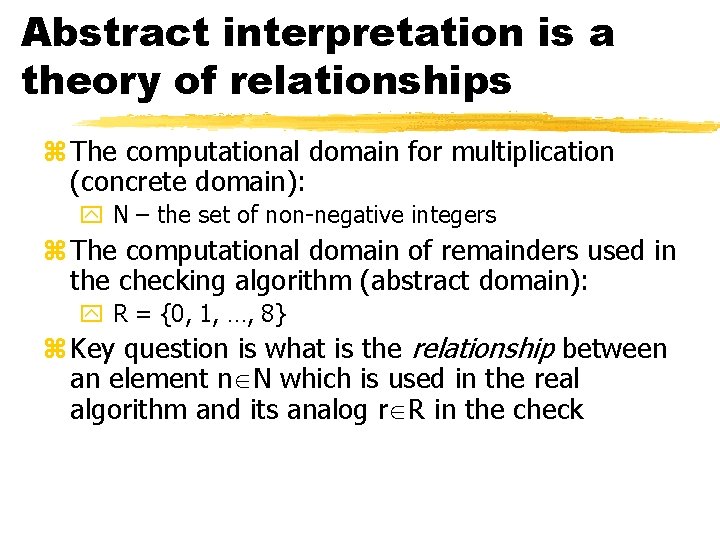

Abstract interpretation is a theory of relationships z The computational domain for multiplication (concrete domain): y N – the set of non-negative integers z The computational domain of remainders used in the checking algorithm (abstract domain): y R = {0, 1, …, 8} z Key question is what is the relationship between an element n N which is used in the real algorithm and its analog r R in the check

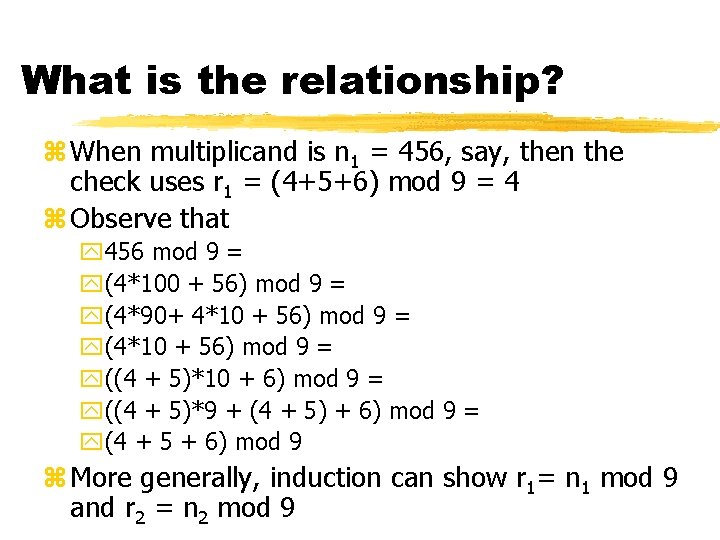

What is the relationship? z When multiplicand is n 1 = 456, say, then the check uses r 1 = (4+5+6) mod 9 = 4 z Observe that y 456 mod 9 = y(4*100 + 56) mod 9 = y(4*90+ 4*10 + 56) mod 9 = y((4 + 5)*10 + 6) mod 9 = y((4 + 5)*9 + (4 + 5) + 6) mod 9 = y(4 + 5 + 6) mod 9 z More generally, induction can show r 1= n 1 mod 9 and r 2 = n 2 mod 9

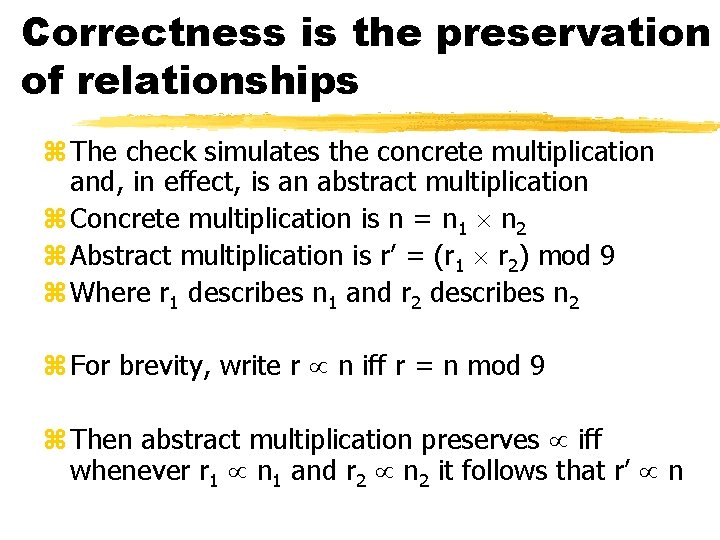

Correctness is the preservation of relationships z The check simulates the concrete multiplication and, in effect, is an abstract multiplication z Concrete multiplication is n = n 1 n 2 z Abstract multiplication is r’ = (r 1 r 2) mod 9 z Where r 1 describes n 1 and r 2 describes n 2 z For brevity, write r n iff r = n mod 9 z Then abstract multiplication preserves iff whenever r 1 n 1 and r 2 n 2 it follows that r’ n

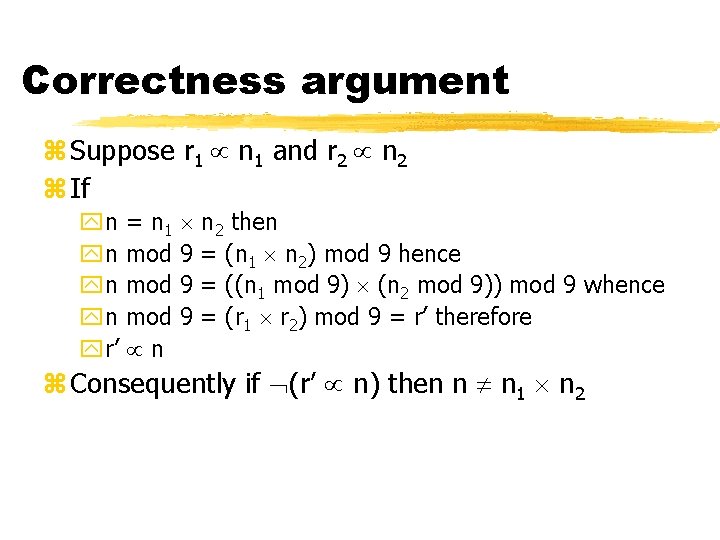

Correctness argument z Suppose r 1 n 1 and r 2 n 2 z If yn = n 1 n 2 then yn mod 9 = (n 1 n 2) mod 9 hence yn mod 9 = ((n 1 mod 9) (n 2 mod 9)) mod 9 whence yn mod 9 = (r 1 r 2) mod 9 = r’ therefore yr’ n z Consequently if (r’ n) then n n 1 n 2

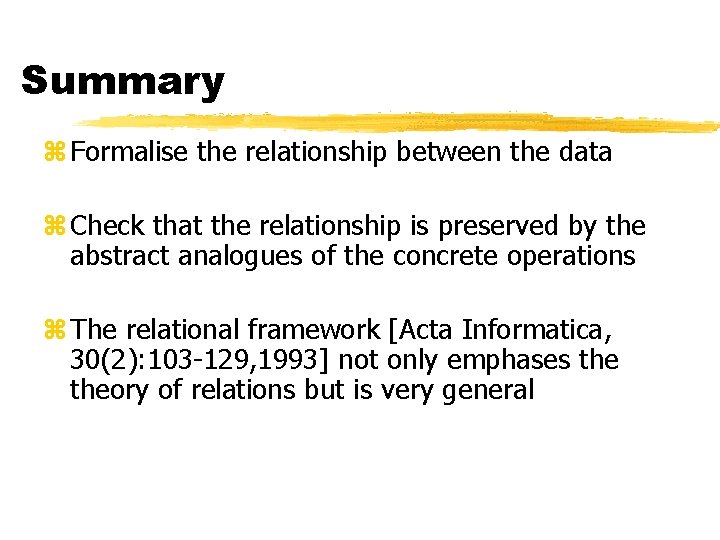

Summary z Formalise the relationship between the data z Check that the relationship is preserved by the abstract analogues of the concrete operations z The relational framework [Acta Informatica, 30(2): 103 -129, 1993] not only emphases theory of relations but is very general

Numeric approximation and widening Abstract interpretation does not require an abstract domain to be finite

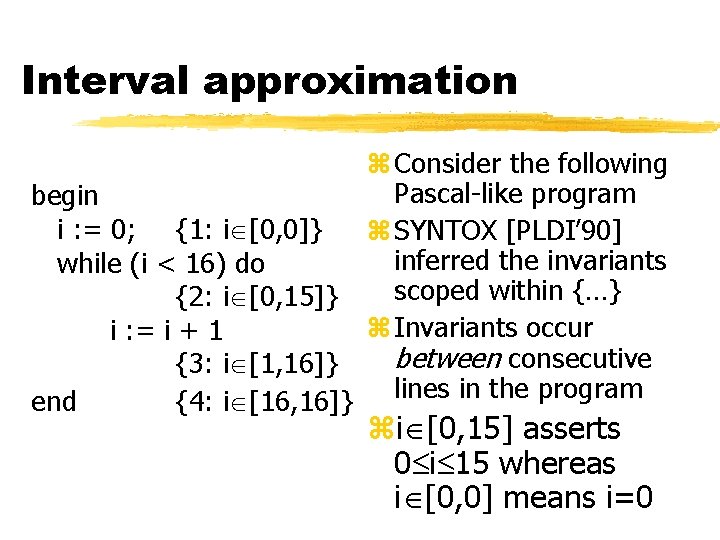

Interval approximation z Consider the following Pascal-like program begin i : = 0; {1: i [0, 0]} z SYNTOX [PLDI’ 90] inferred the invariants while (i < 16) do scoped within {…} {2: i [0, 15]} z Invariants occur i : = i + 1 between consecutive {3: i [1, 16]} end {4: i [16, 16]} lines in the program zi [0, 15] asserts 0 i 15 whereas i [0, 0] means i=0

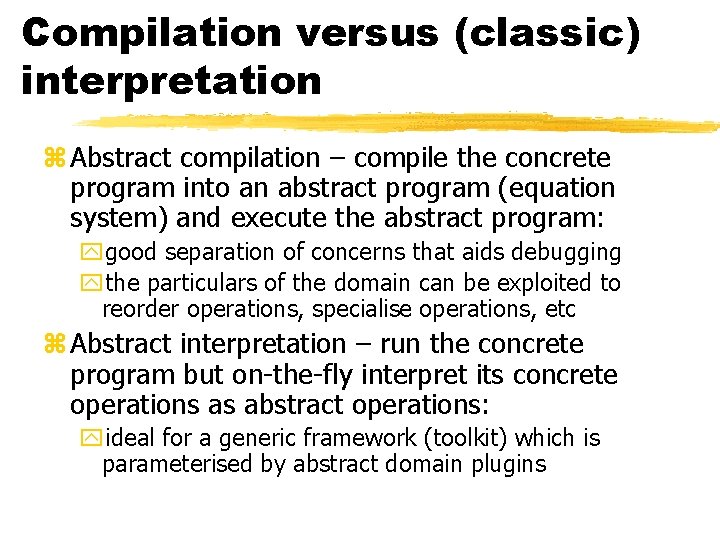

Compilation versus (classic) interpretation z Abstract compilation – compile the concrete program into an abstract program (equation system) and execute the abstract program: ygood separation of concerns that aids debugging ythe particulars of the domain can be exploited to reorder operations, specialise operations, etc z Abstract interpretation – run the concrete program but on-the-fly interpret its concrete operations as abstract operations: yideal for a generic framework (toolkit) which is parameterised by abstract domain plugins

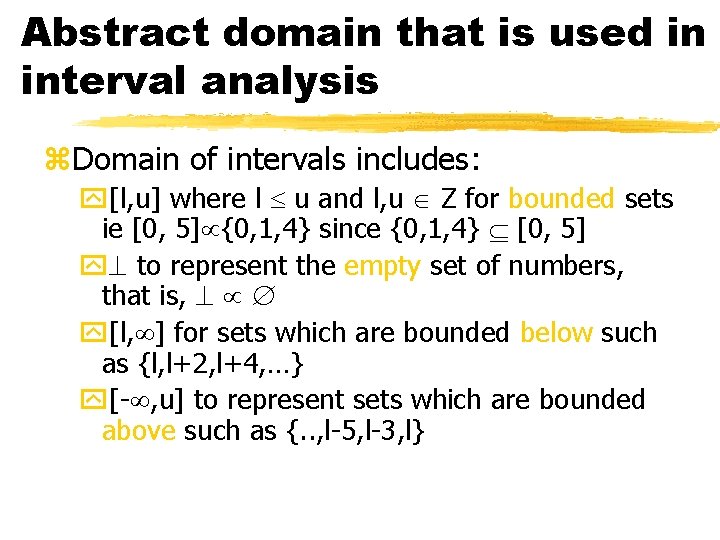

Abstract domain that is used in interval analysis z. Domain of intervals includes: y[l, u] where l u and l, u Z for bounded sets ie [0, 5] {0, 1, 4} since {0, 1, 4} [0, 5] y to represent the empty set of numbers, that is, y[l, ] for sets which are bounded below such as {l, l+2, l+4, …} y[- , u] to represent sets which are bounded above such as {. . , l-5, l-3, l}

![Weakening intervals if … then … {1: i [0, 2]} else … {2: i Weakening intervals if … then … {1: i [0, 2]} else … {2: i](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bce32097250e3e4f491438d4153c8d46/image-15.jpg)

Weakening intervals if … then … {1: i [0, 2]} else … {2: i [3, 5]} endif {3: i [0, 5]} Join (path merge) is defined: y. Put d 1 d 2 = d 1 if d 2 = y d 2 else if d 1 = y [min(l 1, l 2), max(u 1, u 2)] otherwise ywhenever d 1 = [l 1, u 1] and d 2 = [l 2, u 2]

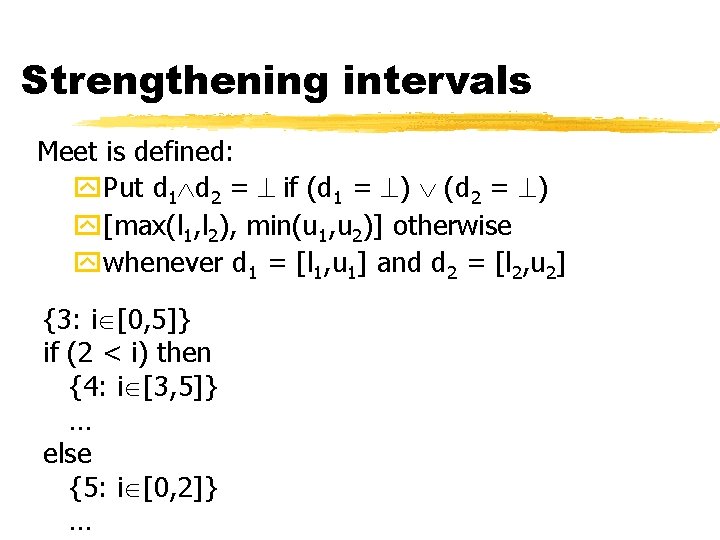

Strengthening intervals Meet is defined: y. Put d 1 d 2 = if (d 1 = ) (d 2 = ) y[max(l 1, l 2), min(u 1, u 2)] otherwise ywhenever d 1 = [l 1, u 1] and d 2 = [l 2, u 2] {3: i [0, 5]} if (2 < i) then {4: i [3, 5]} … else {5: i [0, 2]} …

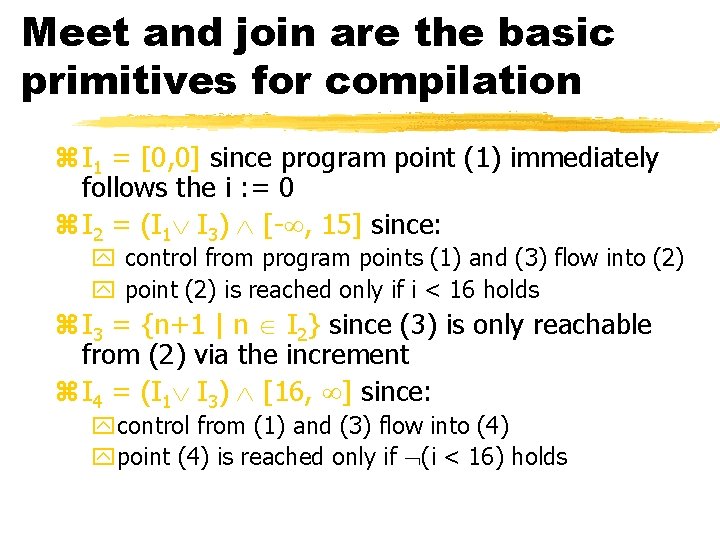

Meet and join are the basic primitives for compilation z I 1 = [0, 0] since program point (1) immediately follows the i : = 0 z I 2 = (I 1 I 3) [- , 15] since: y control from program points (1) and (3) flow into (2) y point (2) is reached only if i < 16 holds z I 3 = {n+1 | n I 2} since (3) is only reachable from (2) via the increment z I 4 = (I 1 I 3) [16, ] since: ycontrol from (1) and (3) flow into (4) ypoint (4) is reached only if (i < 16) holds

![Interval iteration I 1 [0, 0] [0, 0] I 2 I 3 I 4 Interval iteration I 1 [0, 0] [0, 0] I 2 I 3 I 4](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bce32097250e3e4f491438d4153c8d46/image-18.jpg)

Interval iteration I 1 [0, 0] [0, 0] I 2 I 3 I 4 I 1 … [0, 0] [0, 1] [0, 2] [1, 1] [1, 2] [1, 3] [0, 0] I 2 … [0, 15] I 3 … [1, 15] I 4 … [0, 0] [0, 15] [1, 16] [16, 16]

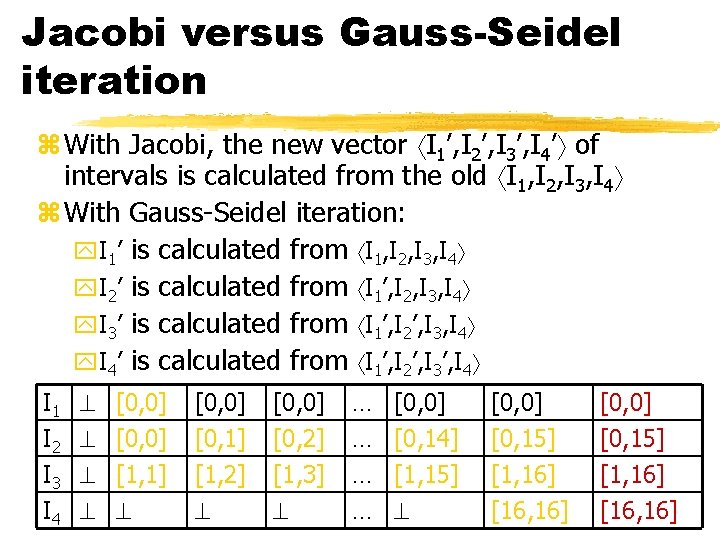

Jacobi versus Gauss-Seidel iteration z With Jacobi, the new vector I 1’, I 2’, I 3’, I 4’ of intervals is calculated from the old I 1, I 2, I 3, I 4 z With Gauss-Seidel iteration: y. I 1’ is calculated from I 1, I 2, I 3, I 4 y. I 2’ is calculated from I 1’, I 2, I 3, I 4 y. I 3’ is calculated from I 1’, I 2’, I 3, I 4 y. I 4’ is calculated from I 1’, I 2’, I 3’, I 4 I 1 I 2 I 3 I 4 [0, 0] [1, 1] [0, 0] [0, 1] [1, 2] [0, 0] [0, 2] [1, 3] … … [0, 0] [0, 14] [1, 15] [0, 0] [0, 15] [1, 16] [16, 16]

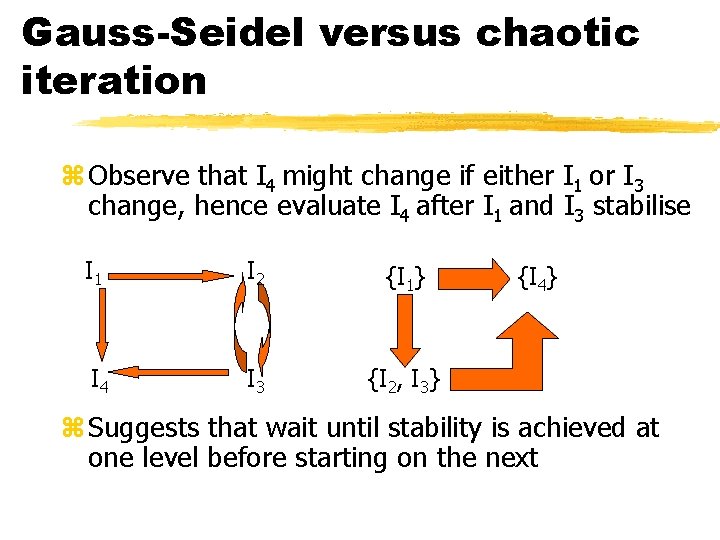

Gauss-Seidel versus chaotic iteration z Observe that I 4 might change if either I 1 or I 3 change, hence evaluate I 4 after I 1 and I 3 stabilise I 1 I 2 {I 1} I 4 I 3 {I 2, I 3} {I 4} z Suggests that wait until stability is achieved at one level before starting on the next

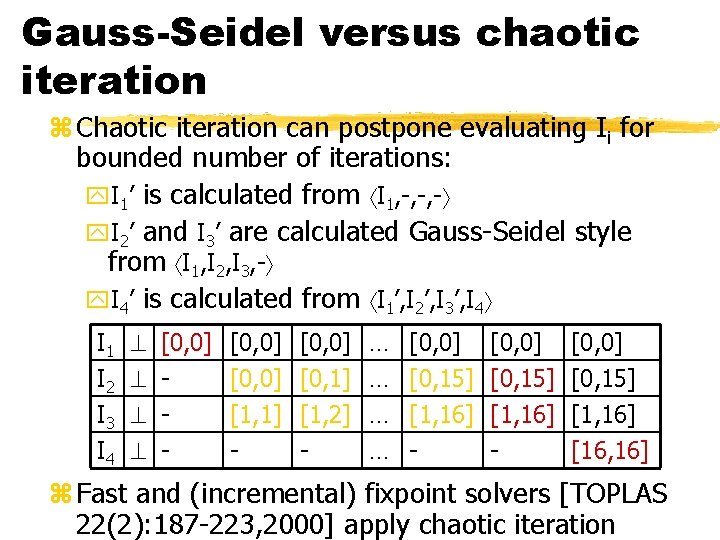

Gauss-Seidel versus chaotic iteration z Chaotic iteration can postpone evaluating Ii for bounded number of iterations: y. I 1’ is calculated from I 1, -, -, - y. I 2’ and I 3’ are calculated Gauss-Seidel style from I 1, I 2, I 3, - y. I 4’ is calculated from I 1’, I 2’, I 3’, I 4 I 1 I 2 I 3 I 4 [0, 0] - [0, 0] [1, 1] - [0, 0] [0, 1] [1, 2] - … … [0, 0] [0, 15] [1, 16] - [0, 0] [0, 15] [1, 16] [16, 16] z Fast and (incremental) fixpoint solvers [TOPLAS 22(2): 187 -223, 2000] apply chaotic iteration

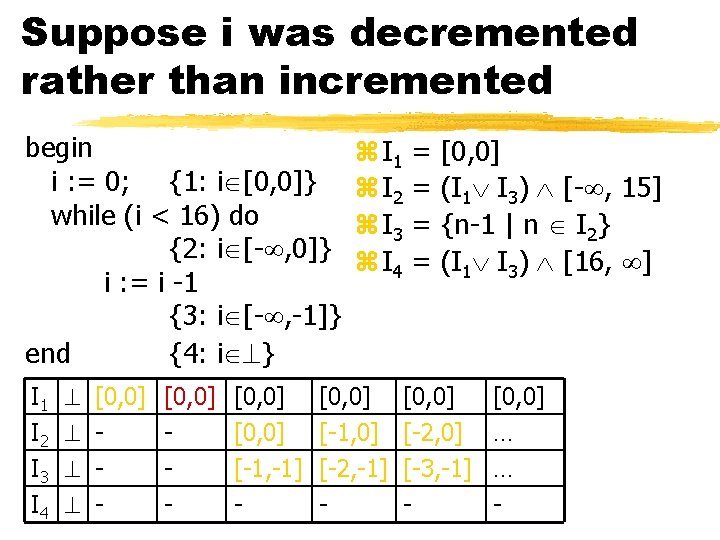

Suppose i was decremented rather than incremented begin i : = 0; {1: i [0, 0]} while (i < 16) do {2: i [- , 0]} i : = i -1 {3: i [- , -1]} end {4: i } I 1 I 2 I 3 I 4 [0, 0] - [0, 0] [-1, -1] - z I 1 z I 2 z I 3 z I 4 [0, 0] [-1, 0] [-2, -1] - = = [0, 0] (I 1 I 3) [- , 15] {n-1 | n I 2} (I 1 I 3) [16, ] [0, 0] [-2, 0] [-3, -1] - [0, 0] … … -

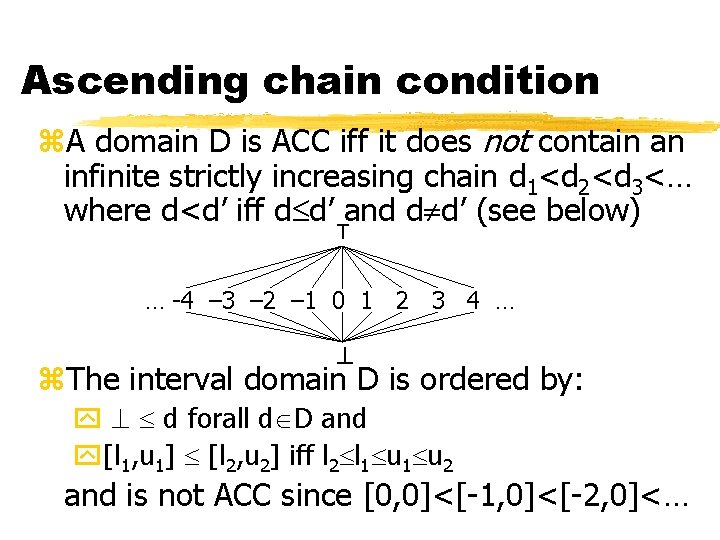

Ascending chain condition z. A domain D is ACC iff it does not contain an infinite strictly increasing chain d 1<d 2<d 3<… where d<d’ iff d d’ and d d’ (see below) T … -4 – 3 – 2 – 1 0 1 2 3 4 … z. The interval domain D is ordered by: y d forall d D and y[l 1, u 1] [l 2, u 2] iff l 2 l 1 u 2 and is not ACC since [0, 0]<[-1, 0]<[-2, 0]<…

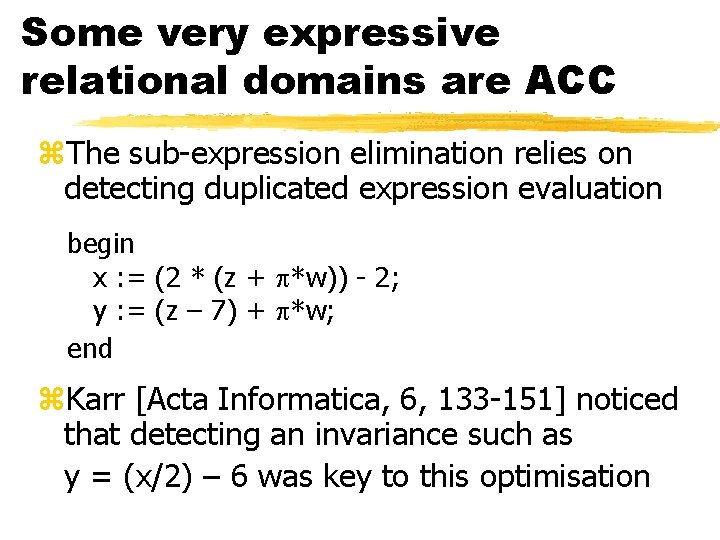

Some very expressive relational domains are ACC z. The sub-expression elimination relies on detecting duplicated expression evaluation begin x : = (2 * (z + *w)) - 2; y : = (z – 7) + *w; end z. Karr [Acta Informatica, 6, 133 -151] noticed that detecting an invariance such as y = (x/2) – 6 was key to this optimisation

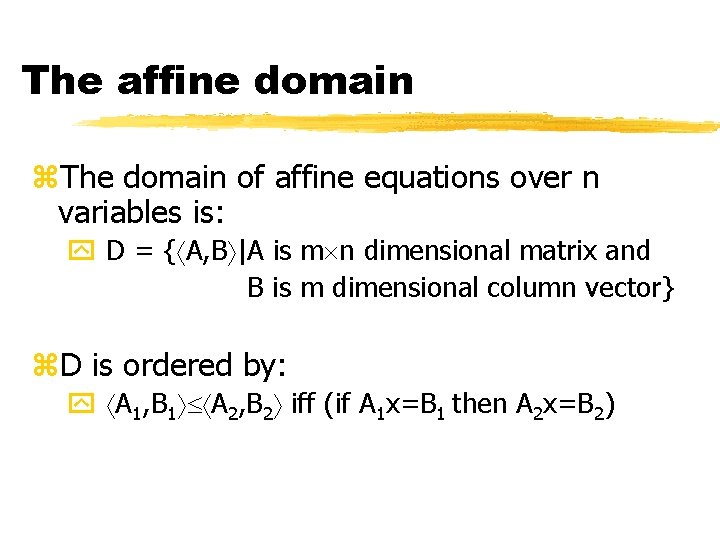

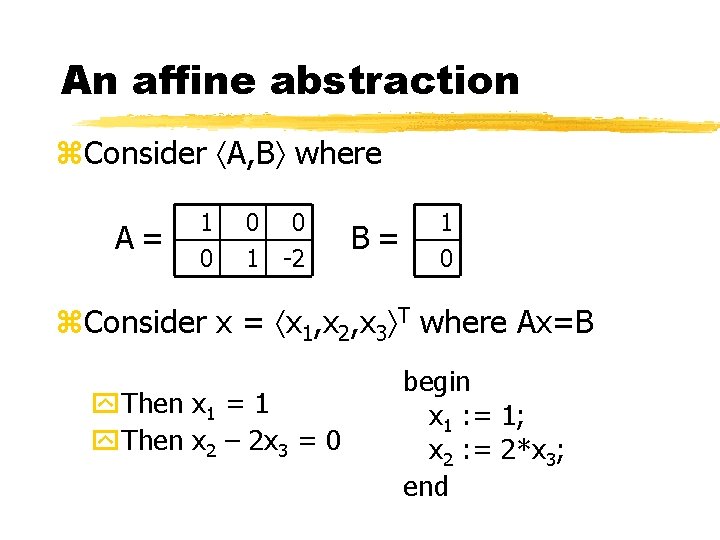

The affine domain z. The domain of affine equations over n variables is: y D = { A, B |A is m n dimensional matrix and B is m dimensional column vector} z. D is ordered by: y A 1, B 1 A 2, B 2 iff (if A 1 x=B 1 then A 2 x=B 2)

An affine abstraction z. Consider A, B where A= 1 0 0 1 0 -2 B= 1 0 z. Consider x = x 1, x 2, x 3 T where Ax=B y. Then x 1 = 1 y. Then x 2 – 2 x 3 = 0 begin x 1 : = 1; x 2 : = 2*x 3; end

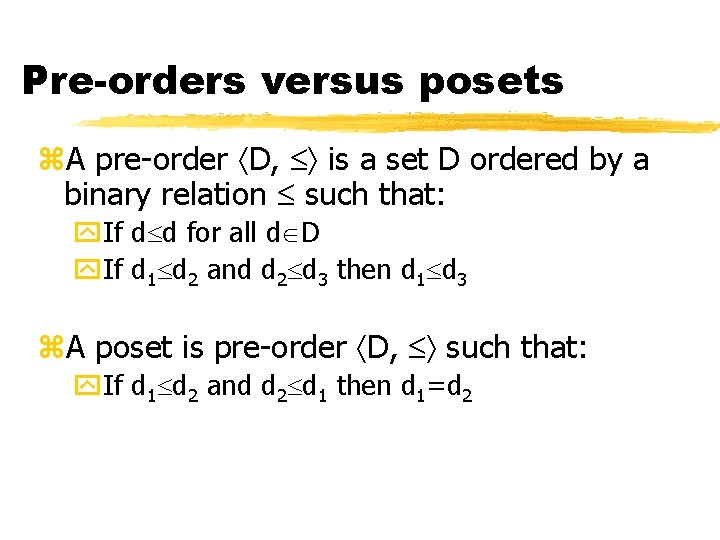

Pre-orders versus posets z. A pre-order D, is a set D ordered by a binary relation such that: y. If d d for all d D y. If d 1 d 2 and d 2 d 3 then d 1 d 3 z. A poset is pre-order D, such that: y. If d 1 d 2 and d 2 d 1 then d 1=d 2

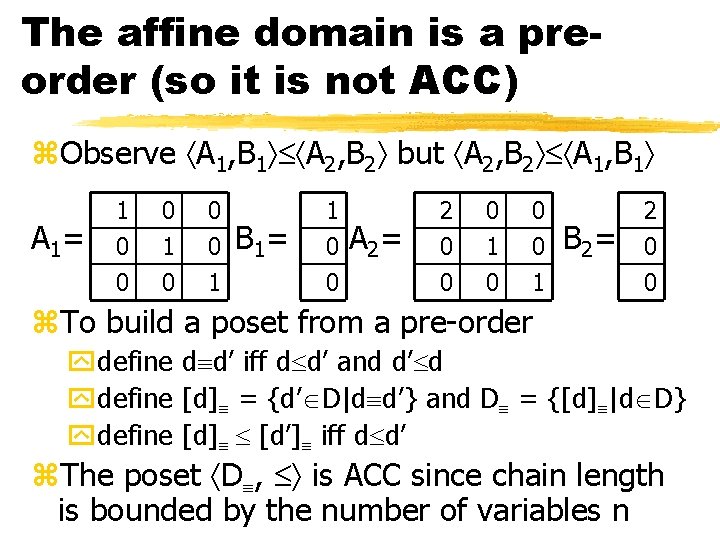

The affine domain is a preorder (so it is not ACC) z. Observe A 1, B 1 A 2, B 2 but A 2, B 2 A 1, B 1 A 1= 1 0 0 0 1 B 1= 1 0 0 A 2= 2 0 0 0 1 B 2= 2 0 0 z. To build a poset from a pre-order ydefine d d’ iff d d’ and d’ d ydefine [d] = {d’ D|d d’} and D = {[d] |d D} ydefine [d] [d’] iff d d’ z. The poset D , is ACC since chain length is bounded by the number of variables n

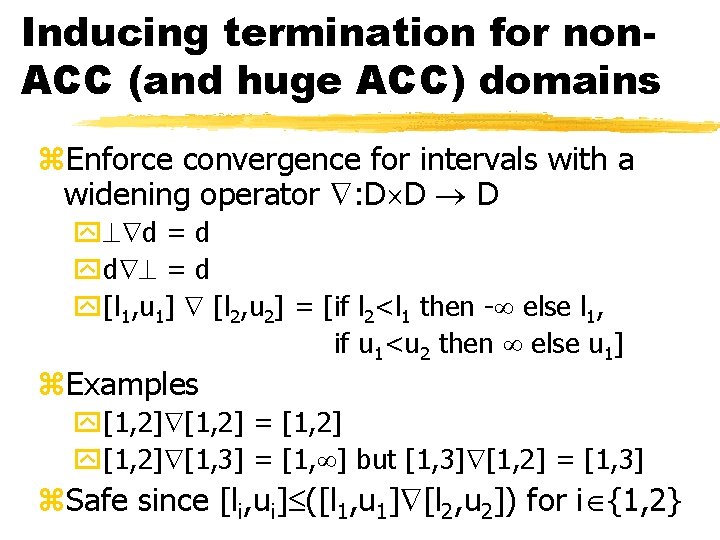

Inducing termination for non. ACC (and huge ACC) domains z. Enforce convergence for intervals with a widening operator : D D D y d = d yd = d y[l 1, u 1] [l 2, u 2] = [if l 2<l 1 then - else l 1, if u 1<u 2 then else u 1] z. Examples y[1, 2] = [1, 2] y[1, 2] [1, 3] = [1, ] but [1, 3] [1, 2] = [1, 3] z. Safe since [li, ui] ([l 1, u 1] [l 2, u 2]) for i {1, 2}

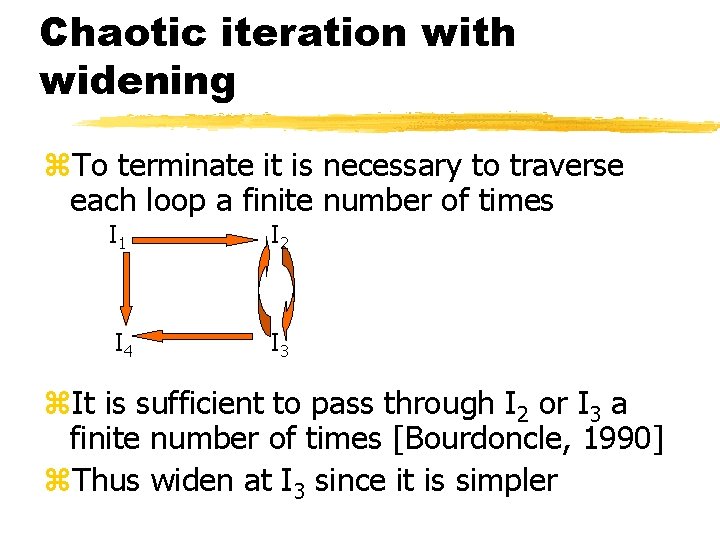

Chaotic iteration with widening z. To terminate it is necessary to traverse each loop a finite number of times I 1 I 2 I 4 I 3 z. It is sufficient to pass through I 2 or I 3 a finite number of times [Bourdoncle, 1990] z. Thus widen at I 3 since it is simpler

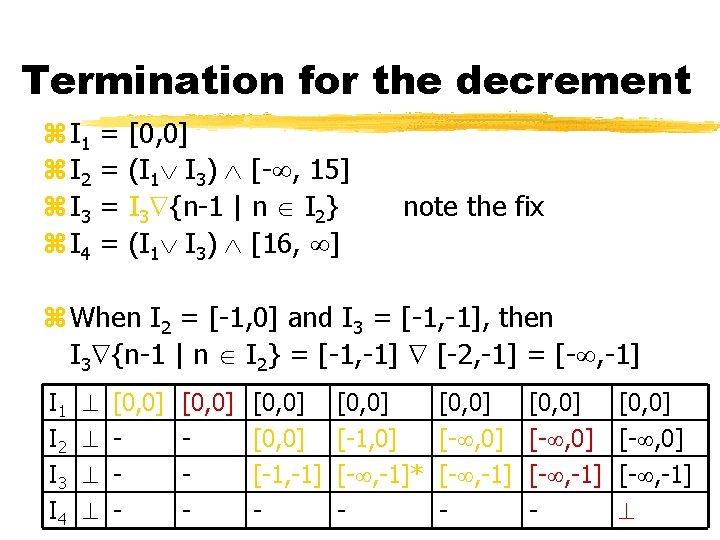

Termination for the decrement z I 1 z I 2 z I 3 z I 4 = = [0, 0] (I 1 I 3) [- , 15] I 3 {n-1 | n I 2} (I 1 I 3) [16, ] note the fix z When I 2 = [-1, 0] and I 3 = [-1, -1], then I 3 {n-1 | n I 2} = [-1, -1] [-2, -1] = [- , -1] I 1 I 2 I 3 I 4 [0, 0] - [0, 0] [-1, -1] - [0, 0] [- , 0] [-1, 0] [- , -1]* [- , -1] -

(Malicious) research challenge z. Read a survey paper to find an abstract domain that is ACC but has a maximal chain length of O(2 n) z. Construct a program with O(n) symbols that iterates through all O(2 n) abstractions z. Publish the program in IPL

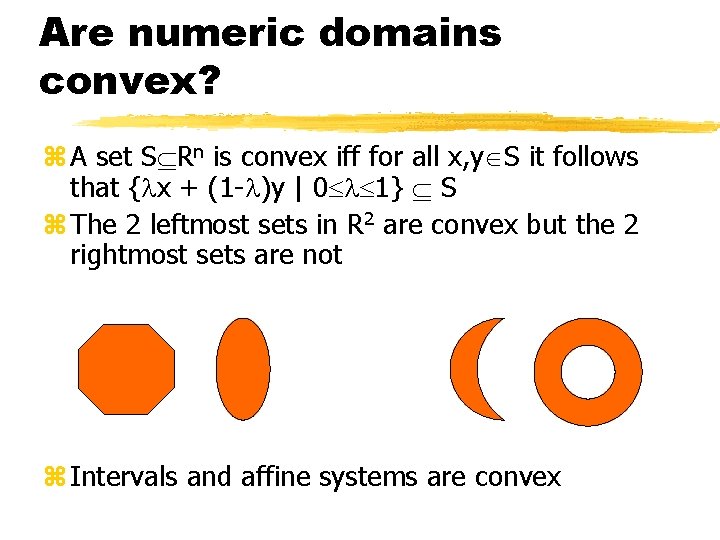

Are numeric domains convex? z A set S Rn is convex iff for all x, y S it follows that { x + (1 - )y | 0 1} S z The 2 leftmost sets in R 2 are convex but the 2 rightmost sets are not z Intervals and affine systems are convex

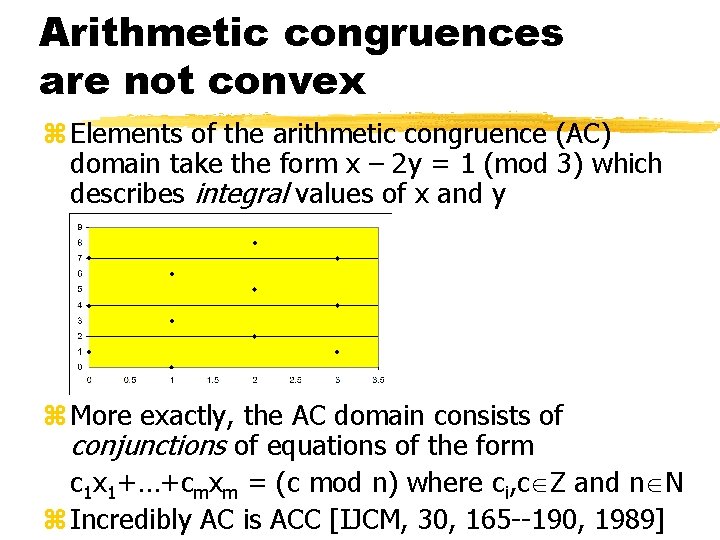

Arithmetic congruences are not convex z Elements of the arithmetic congruence (AC) domain take the form x – 2 y = 1 (mod 3) which describes integral values of x and y z More exactly, the AC domain consists of conjunctions of equations of the form c 1 x 1+…+cmxm = (c mod n) where ci, c Z and n N z Incredibly AC is ACC [IJCM, 30, 165 --190, 1989]

![Research challenge z. Søndergaard [FSTTCS, 95] introduced the concept of an immediate fixpoint z. Research challenge z. Søndergaard [FSTTCS, 95] introduced the concept of an immediate fixpoint z.](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/bce32097250e3e4f491438d4153c8d46/image-35.jpg)

Research challenge z. Søndergaard [FSTTCS, 95] introduced the concept of an immediate fixpoint z. Consider the following (groundness) dependency equations over the domain of Boolean functions Bool, , yf 1 yf 2 yf 3 yf 4 = = x (y z) t( x( z(u (t x) v (t z) f 4))) u ( v(x u z v f 2)) f 1 f 3 z. Where x(f) = f[x true] f[x false] thus x(x y) = true and x(x y) = y

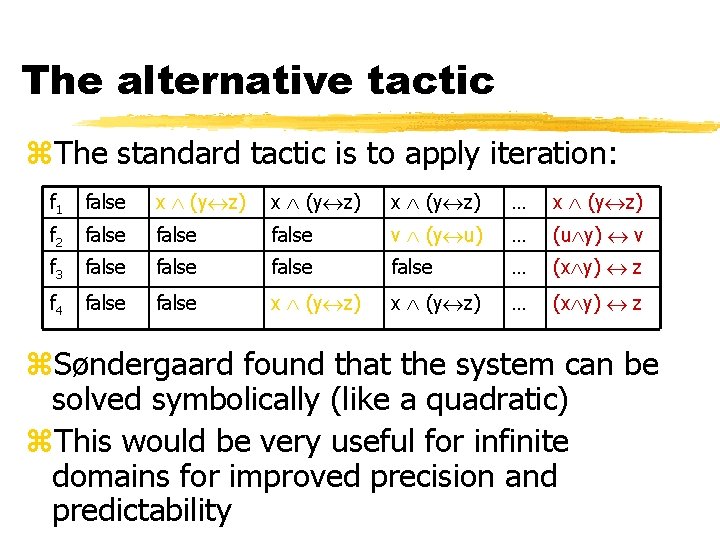

The alternative tactic z. The standard tactic is to apply iteration: f 1 false x (y z) … x (y z) f 2 false v (y u) … (u y) v f 3 false … (x y) z f 4 false x (y z) … (x y) z z. Søndergaard found that the system can be solved symbolically (like a quadratic) z. This would be very useful for infinite domains for improved precision and predictability

Combining analyses z. Verifiers and optimisers are often multipass, built from several separate analyses z. Should the analyses be performed in parallel or in sequence? z. Analyses can interact to improve one another (problem is in the complexity of the interaction [Pratt])

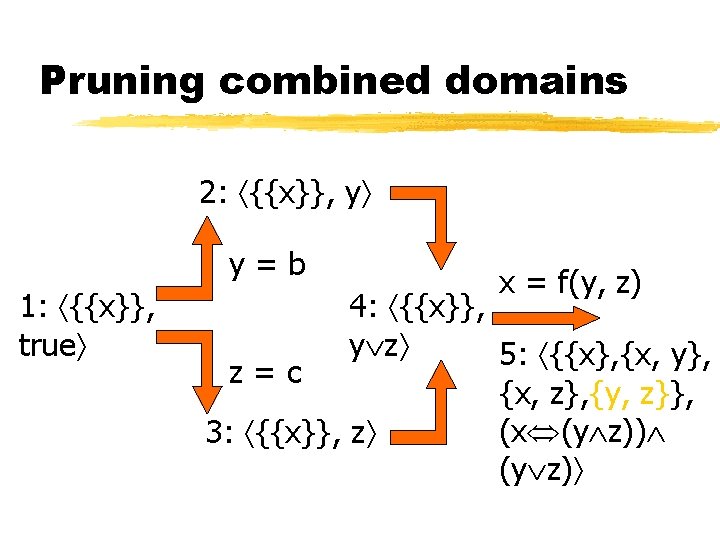

Pruning combined domains 2: {{x}}, y y=b 1: {{x}}, true x = f(y, z) 4: {{x}}, y z 5: {{x}, {x, y}, z=c {x, z}, {y, z}}, (x (y z)) 3: {{x}}, z (y z)

Pruning combined domains z. Suppose that 1 D 1 C and 2 D 2 C, then how is D=D 1 D 2 interpreted? z. Then d 1, d 2 c iff d 1 1 c d 2 2 c z. Ideally, many d 1, d 2 D will be redundant, that is, c C. c 1 d 1 c 2 d 2

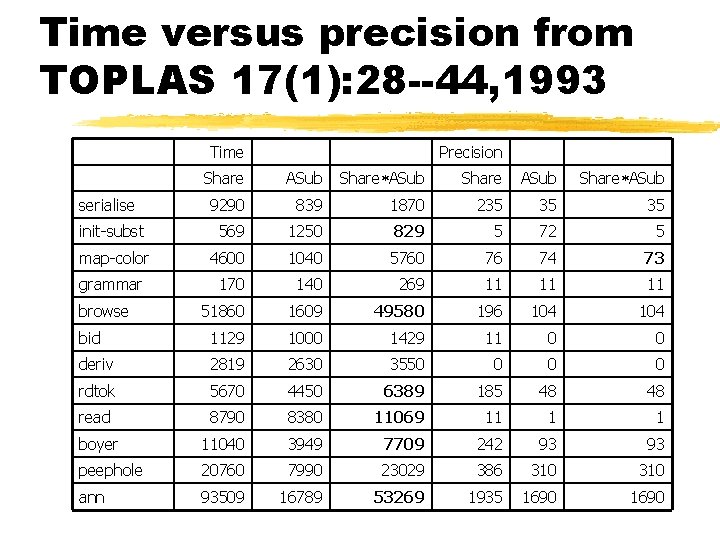

Time versus precision from TOPLAS 17(1): 28 --44, 1993 Time Precision Share ASub serialise 9290 839 1870 235 35 35 init-subst 569 1250 829 5 72 5 map-color 4600 1040 5760 76 74 73 grammar 170 140 269 11 11 11 51860 1609 49580 196 104 bid 1129 1000 1429 11 0 0 deriv 2819 2630 3550 0 rdtok 5670 4450 6389 185 48 48 read 8790 8380 11069 11 1 1 boyer 11040 3949 7709 242 93 93 peephole 20760 7990 23029 386 310 ann 93509 16789 53269 1935 1690 browse

The Galois framework Abstract interpretation is classically presented in terms of Galois connections

Lattices – a prelude to Galois connections z Suppose S, is a poset z A mapping : S S S is a join (least upper bound) iff ya b is an upper bound of a and b, that is, a a b and b a b for all a, b S ya b is the least upper bound, that is, if c S is an upper bound of a and b, then a b c z The definition of the meet : S S S (the greatest lower bound) is analogous

Complete lattices z A lattice S, , , is a poset S, equipped with a join and a meet z The join concept can often be lifted to sets by defining : (S) S iff yt ( T) for all T S and for all t T yif t s for all t T then ( T) s z If meet can often be lifted analogously, then the lattice is complete z A lattice that contains a finite number of elements is always complete

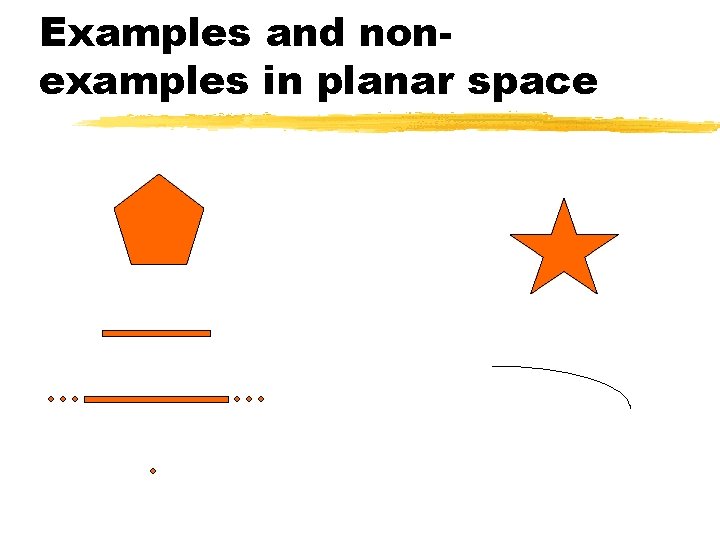

A lattice that is not complete z. A hyperplane in 2 -d space in a line and in 3 -d space is a plane z. A hyperplane in Rn is any space that can be defined by {x Rn | c 1 x 1+…+cnxn = c} where c 1, …, cn, c R z. A halfspace in Rn is any space that can be defined by {x Rn | c 1 x 1+…+cnxn c} z. A polyhedron is the intersection of a finite number of half-spaces

Examples and nonexamples in planar space

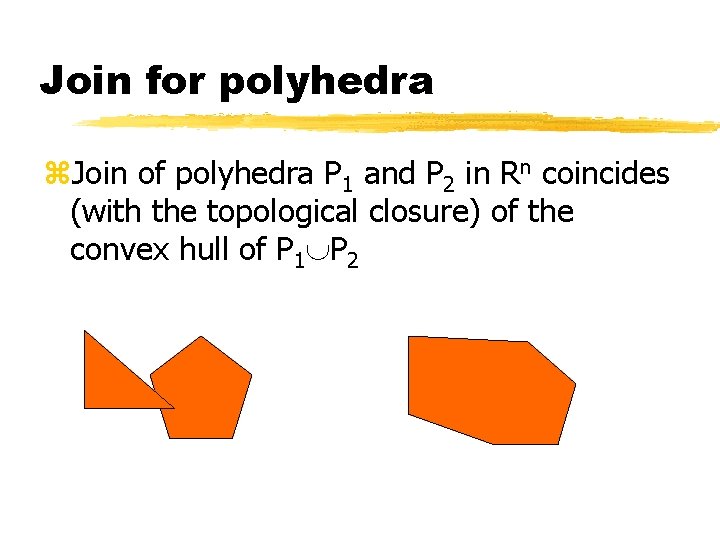

Join for polyhedra z. Join of polyhedra P 1 and P 2 in Rn coincides (with the topological closure) of the convex hull of P 1 P 2

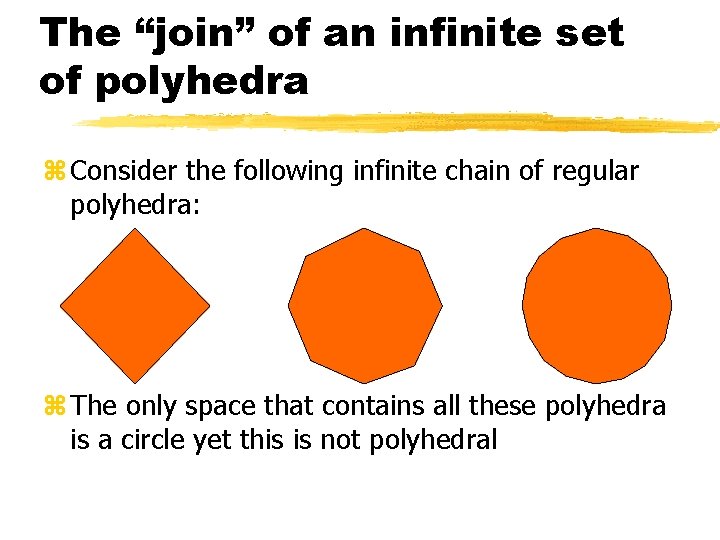

The “join” of an infinite set of polyhedra z Consider the following infinite chain of regular polyhedra: z The only space that contains all these polyhedra is a circle yet this is not polyhedral

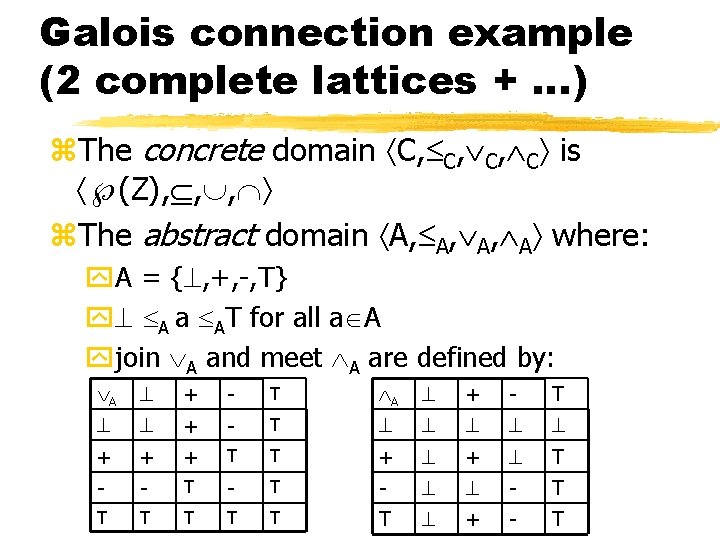

Galois connection example (2 complete lattices + …) z. The concrete domain C, C, C, C is (Z), , , z. The abstract domain A, A, A, A where: y. A = { , +, -, T} y A a AT for all a A yjoin A and meet A are defined by: A + - T + + + T T + + T - - T - - T T T T + - T

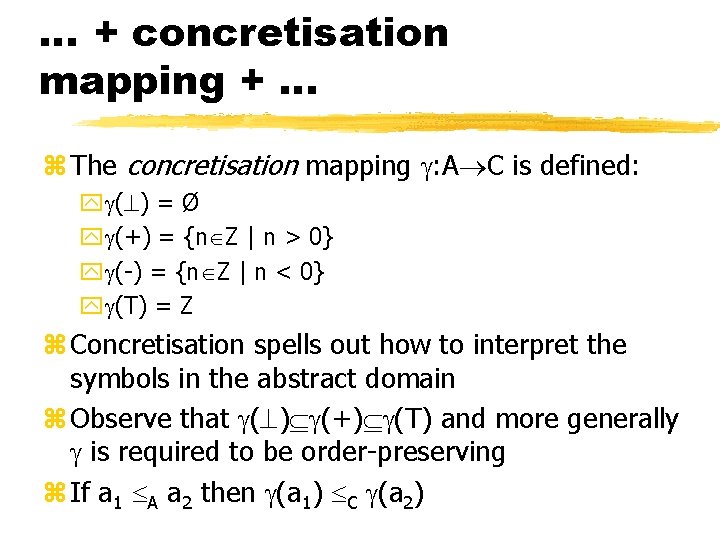

… + concretisation mapping + … z The concretisation mapping : A C is defined: y ( ) = Ø y (+) = {n Z | n > 0} y (-) = {n Z | n < 0} y (T) = Z z Concretisation spells out how to interpret the symbols in the abstract domain z Observe that ( ) (+) (T) and more generally is required to be order-preserving z If a 1 A a 2 then (a 1) C (a 2)

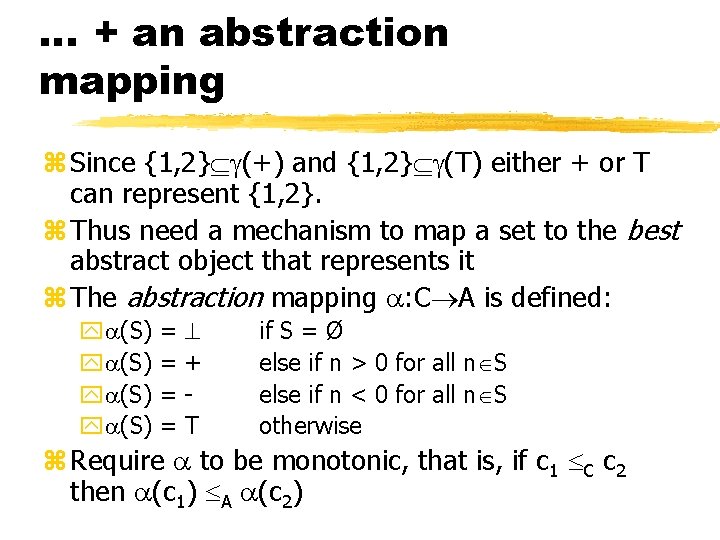

… + an abstraction mapping z Since {1, 2} (+) and {1, 2} (T) either + or T can represent {1, 2}. z Thus need a mechanism to map a set to the best abstract object that represents it z The abstraction mapping : C A is defined: y (S) = = + T if S = Ø else if n > 0 for all n S else if n < 0 for all n S otherwise z Require to be monotonic, that is, if c 1 C c 2 then (c 1) A (c 2)

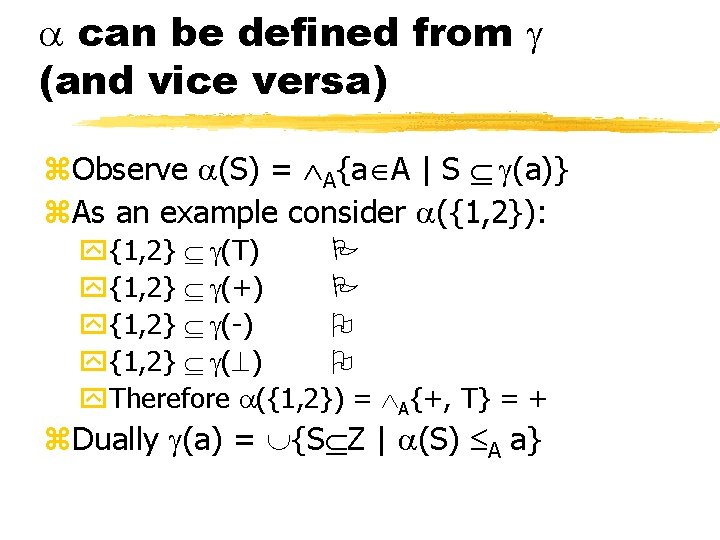

can be defined from (and vice versa) z. Observe (S) = A{a A | S (a)} z. As an example consider ({1, 2}): y{1, 2} (T) y{1, 2} (+) y{1, 2} (-) y{1, 2} ( ) y. Therefore ({1, 2}) = A{+, T} = + z. Dually (a) = {S Z | (S) A a}

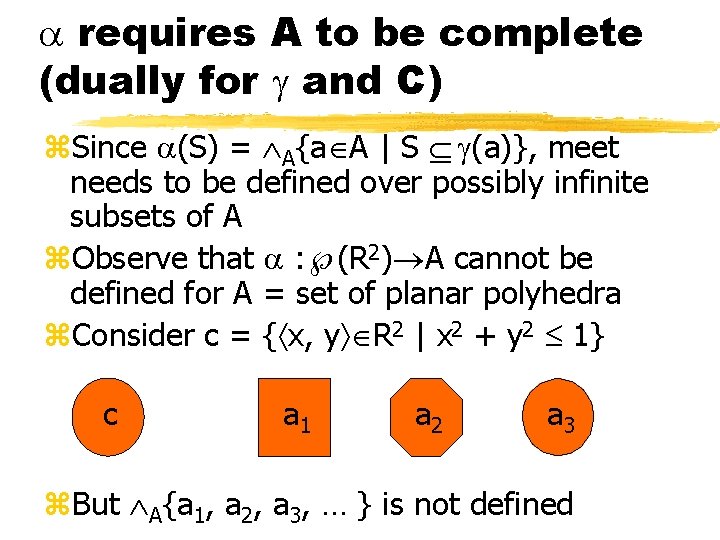

requires A to be complete (dually for and C) z. Since (S) = A{a A | S (a)}, meet needs to be defined over possibly infinite subsets of A z. Observe that : (R 2) A cannot be defined for A = set of planar polyhedra z. Consider c = { x, y R 2 | x 2 + y 2 1} c a 1 a 2 a 3 z. But A{a 1, a 2, a 3, … } is not defined

A, , C, is Galois connection whenever z A, A and C, C are complete lattices z The mappings : C A and : A C are monotonic, that is, y. If c 1 C c 2 then (c 1) A (c 2) y. If a 1 A a 2 then (a 1) C (a 2) z The compositions : A A and : C C are extensive and reductive respectively, that is, yc C ( )(c) for all c C y( )(a) A a for all a A

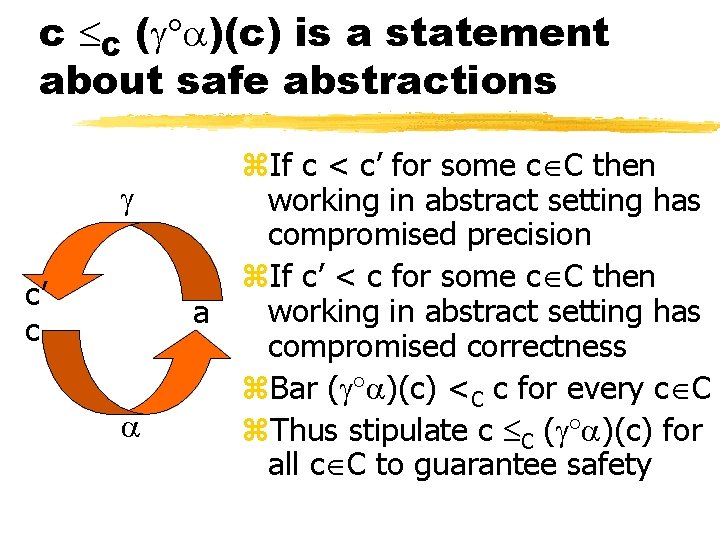

c C ( )(c) is a statement about safe abstractions c’ c z. If c < c’ for some c C then working in abstract setting has compromised precision z. If c’ < c for some c C then working in abstract setting has a compromised correctness z. Bar ( )(c) <C c for every c C z. Thus stipulate c C ( )(c) for all c C to guarantee safety

( )(a) A a is a statement about best abstractions z. Recall that (a) spells out what a A represents z. Thus a is one way to describe (a); T is another way to describe (a) but a is better since a A T z. Desire ( (a)) to be the best way to describe (a) z. Therefore require ( (a)) A a

Collecting domains and semantics z Observe that C is not that concrete – programs include operations such as *: Z Z Z z C= (Z) is collecting domain which is easier to abstract than Z since it already a lattice z To abstract *: Z Z Z, say, we synthesise a collecting version *C: (Z) (Z) and then abstract that z Put S 1 *C S 2 = {n 1*n 2 | n 1 S 1 and n 2 S 2}

Safety and optimality requirements z The most precise (optimal) way to define *A: A A A is to define a 1 *A a 2 = ( (a 1)*C (a 2)) z Not practical since (a 1) and (a 2) are infinite z Handcraft computable *’A: A A A with a 1 *A a 2 A a 1 *’A a 2 for all a 1, a 2 A z Merely need to assert ( (a 1)*C (a 2)) A a 1 *’A a 2 for all a 1, a 2 A for correctness

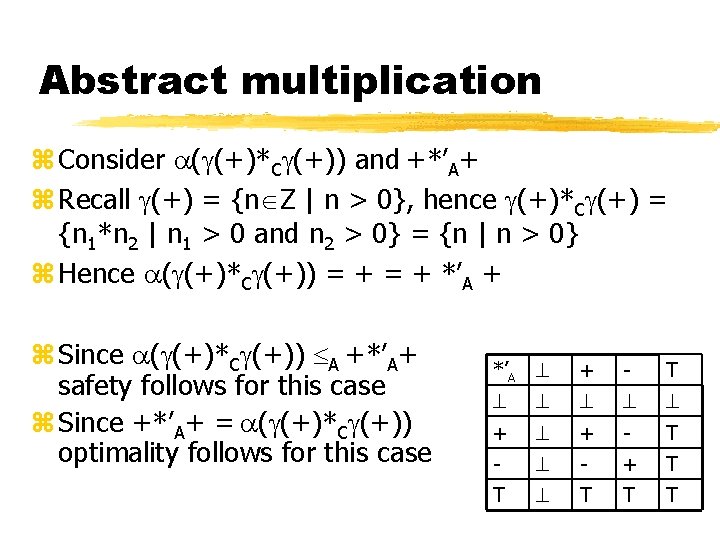

Abstract multiplication z Consider ( (+)*C (+)) and +*’A+ z Recall (+) = {n Z | n > 0}, hence (+)*C (+) = {n 1*n 2 | n 1 > 0 and n 2 > 0} = {n | n > 0} z Hence ( (+)*C (+)) = + *’A + z Since ( (+)*C (+)) A +*’A+ safety follows for this case z Since +*’A+ = ( (+)*C (+)) optimality follows for this case *’A + - T + + - T - - + T T T

Exotic applications of abstract interpretation z Recovering programmer intentions for understanding undocumented or third-party code z Verifying that a buffer-over cannot occur, or pinpointing where one might occur in a C program z Inferring the environment in which is a system of synchronising agents will not deadlock z Lower-bound time-complexity analysis for granularity throttling z Binding-time analysis for inferring off-line unfolding decisions which avoid code-bloat

- Slides: 59