Introduction Contd Aristotles Metaphysics begins 21 25 Metaphysics

Introduction Cont’d

Aristotle’s Metaphysics begins: • Πάντες ἄνθρωποι τοῦ εἰδέναι ὀρέγονται φύσει. σημεῖον δ’ (21) ἡ τῶν αἰσθήσεων ἀγάπησις· καὶ γὰρ χωρὶς τῆς χρείας ἀγαπῶνται δι’ αὑτάς, καὶ μάλιστα τῶν ἄλλων ἡ διὰ τῶν ὀμμάτων. οὐ γὰρ μόνον ἵνα πράττωμεν ἀλλὰ καὶ μηθὲν μέλλοντες πράττειν τὸ ὁρᾶν αἱρούμεθα ἀντὶ πάντων ὡς εἰπεῖν (25) τῶν ἄλλων. αἴτιον δ’ ὅτι μάλιστα ποιεῖ γνωρίζειν ἡμᾶς αὕτη τῶν αἰσθήσεων καὶ πολλὰς δηλοῖ διαφοράς. (Metaphysics 1. 1, 980 a 21 -27) • All men by nature desire to know. And indication of this is the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all other the sense of sight. For not only with a view to action, but even when we are not going to do anything, we prefer sight to almost everything else, makes us know and brings to light many differences between things. (Jonathan Lear’s translation, 1988)

Footnotes • Curiosity is not the best way to conceptualize what drives men on. There must be something in us that drives us to take advantage of the world’s structure. We want to know WHY they occur. • If the knowledge we pursued were merely a means to a further end, then our innate desire would not be a desire for knowledge. And the fact that we take pleasure in the sheer exercise of our sensory faculties is a sign that we do have a desire for knowledge. Leisure was of the utmost importance to Aristotle. It was only after men had developed the arts to help them cope with the necessities of life that they were able to turn to sciences which are not aimed at securing any practical end. • It is out of wonder, Aristotle says, that men begin to philosophize. Philosophy grows out of man’s natural capacity to feel puzzlement and awe. This discontent is of a piece with the desire to know.

Aristotle’s classification of the sciences • Aristotle’s classification of the sciences (a) theoretical sciences, which aim at knowledge for its own sake; (b) the practical sciences, which aim at knowledge as a guide to conduct; (c) the productive sciences, which aim at knowledge to be used in making something useful or beautiful. • The theoretical sciences are subdivided into theology (or metaphysics), physics, and mathematics. (a) physics deals with things that have a separate existence but are not unchangeable; (b) mathematics deals with things that are unchangeable but have no separate existence; (c) theology deals with things that both have separate existence and are unchangeable.

Aristotle’s Physics 1. 1

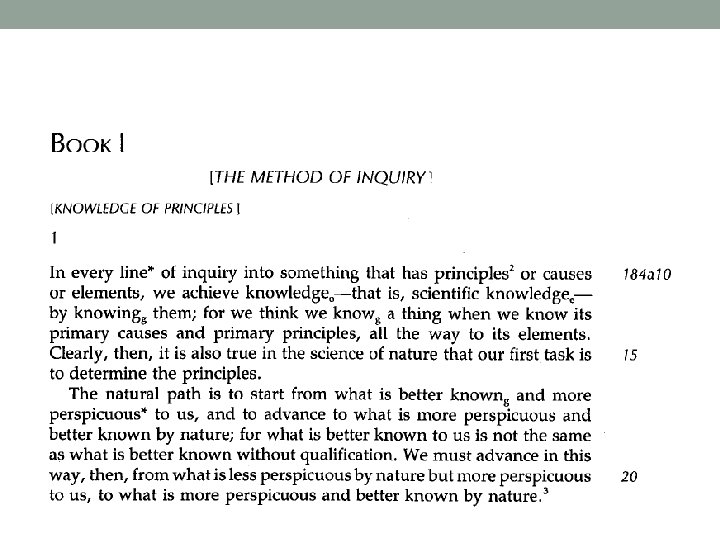

Technical terms • Principle (ἀρχή) (or origin, source) • Cause (αἴτιον) (or explanation) • Element (στοιχεῖον) • Systematic knowledge (ἐπιστήμη): It can be restricted to knowledge of things which can be proved such as the propositions of geometry (Analytic Posterior 2. 3, 90 b 9 -10). It is also used, however, of disciplines which do not make use of strict proofs. • Nature (φύσις): It appears from Physics II that Aristotle does not recognize any such thing as nature over and above the natures of particular things, but here the word is used for physical things generally.

What is clear by nature • What is more perspicuous and better known by nature (τὰ σαφέστερα • • τῇ φύσει καὶ γνωριμώτερα, Physics 1. 1, 184 a 17 -18) What is clear to the learner What is clear by nature = What is clear in itself What are things by nature clear to us? Are they formulations such as principles or elements? Or compounds such as perceptible objects? “We may take him as saying: ‘of the ultimate constituents of matter, pure water, pure fire, or whatever they may be, we know little; about things like houses and doctors, on the other hand, we are fairly clear; let us begin, then, with them, and see what emerges, from a discussion of such familiar objects, about basic principles. ’” (William Charlton, Aristotle Physics Books I and II, 2006, 52)

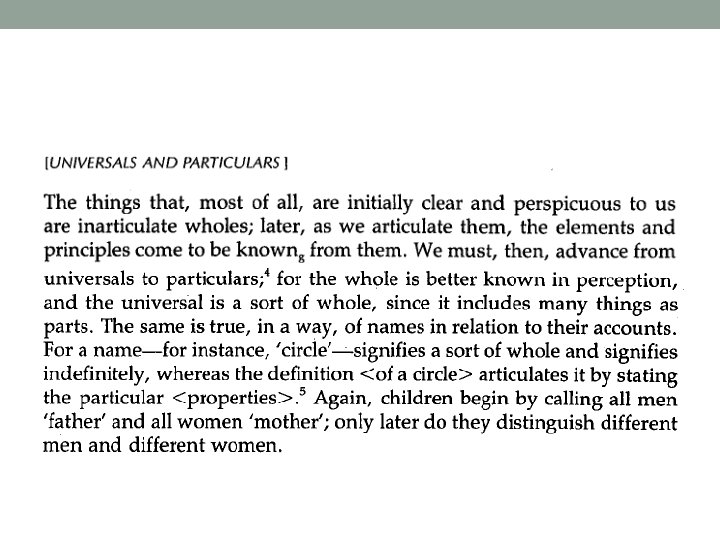

From the universal to the particular • The universal • The particular • The individual is known before the universal (Analytic Posterior 2. 19) • What we perceive is individual (Nicomachean Ethics 7. 4, 1147 a 26) • “The natural course is first to give a general account and then consider the peculiarities of particular cases. ” (Charlton, 52) In Physics Aristotle is concerned about the principles of physical objects generally, without distinguishing products of nature and products of art. “In a way this is reasonable: having set up his general form-matter distinction, Aristotle can later inquire into the formal and material elements in different sorts of thing. ” (Charlton, 52)

Names in relation to their accounts • “We perceive individuals, but our perception is of the universal, e. g. , of man (or perhaps of a man) not of the man Callias (Analytic Posterior 2. 19, 100 a 16 -b 1). ” (Charlton, 52) On the other hand, De Anima 2. 6 suggests that forms like man are not strictly objects of perception. • Name (ὄνομα) • Account (λόγος) • Names in relation to their accounts A name like man indicates a number of features such as animal, rational, mortal, which appear separately in the definition (Philoponus, c. 490 -c. 570, 6 th century Aristotelian commentator)

Aristotle’s Physics 1. 2 -4

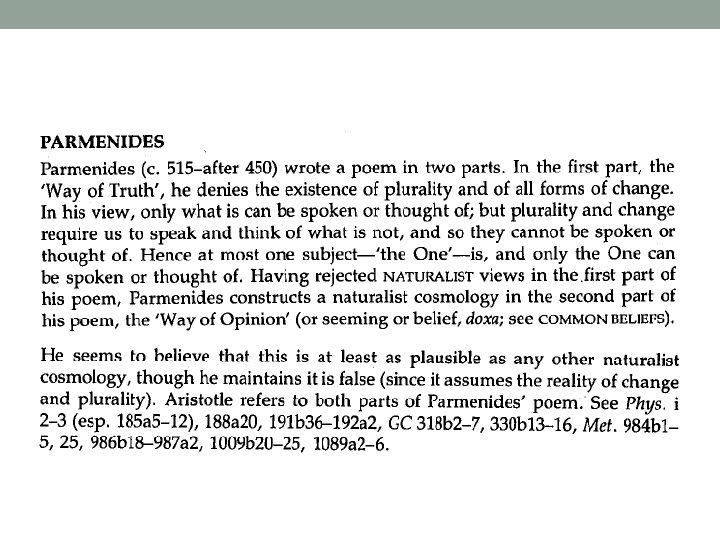

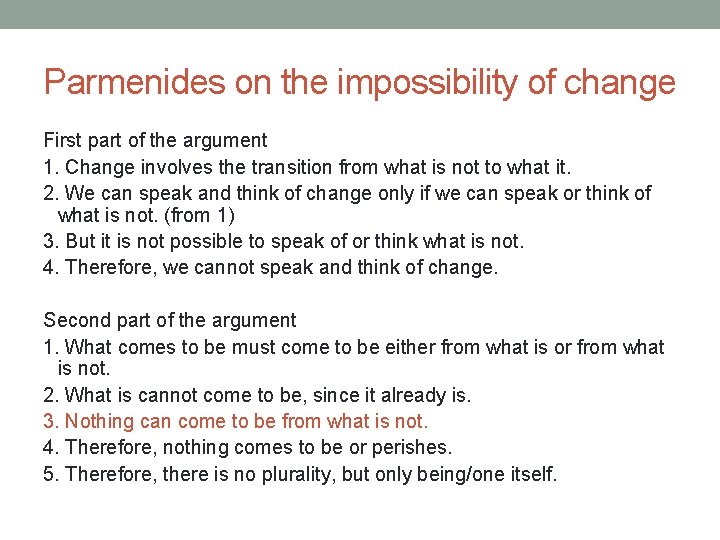

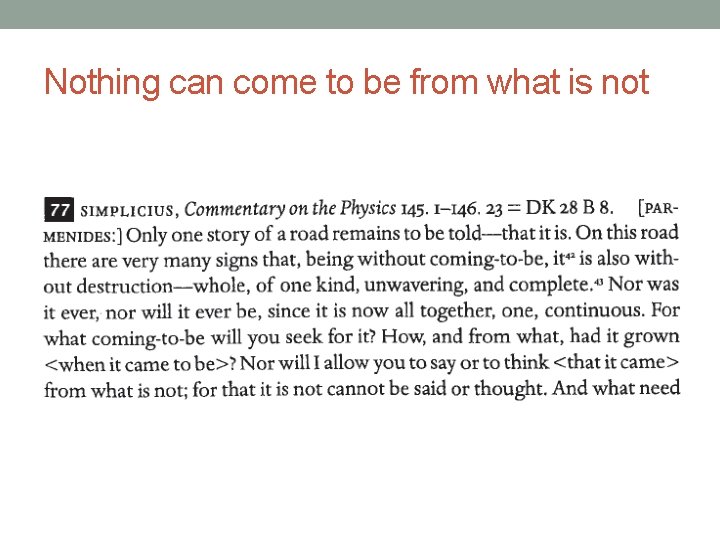

Parmenides on the impossibility of change First part of the argument 1. Change involves the transition from what is not to what it. 2. We can speak and think of change only if we can speak or think of what is not. (from 1) 3. But it is not possible to speak of or think what is not. 4. Therefore, we cannot speak and think of change. Second part of the argument 1. What comes to be must come to be either from what is or from what is not. 2. What is cannot come to be, since it already is. 3. Nothing can come to be from what is not. 4. Therefore, nothing comes to be or perishes. 5. Therefore, there is no plurality, but only being/one itself.

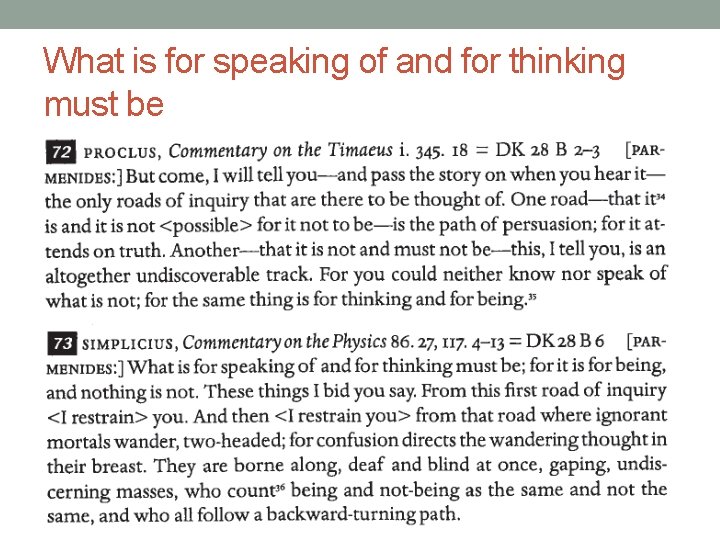

What is for speaking of and for thinking must be

Nothing can come to be from what is not

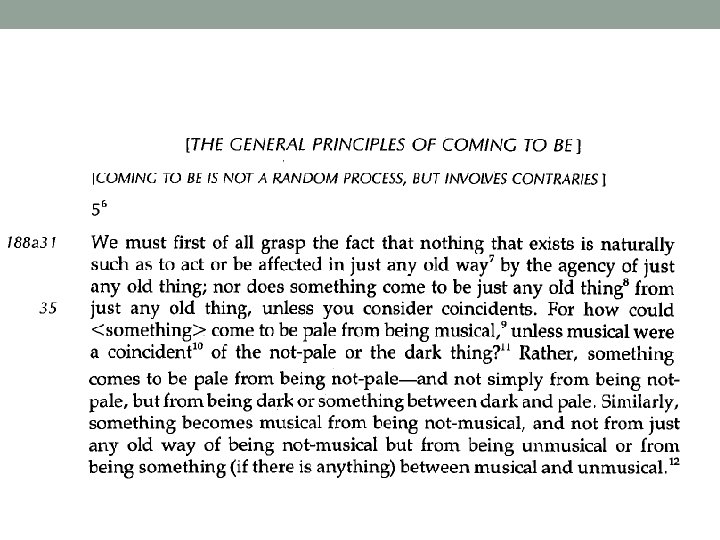

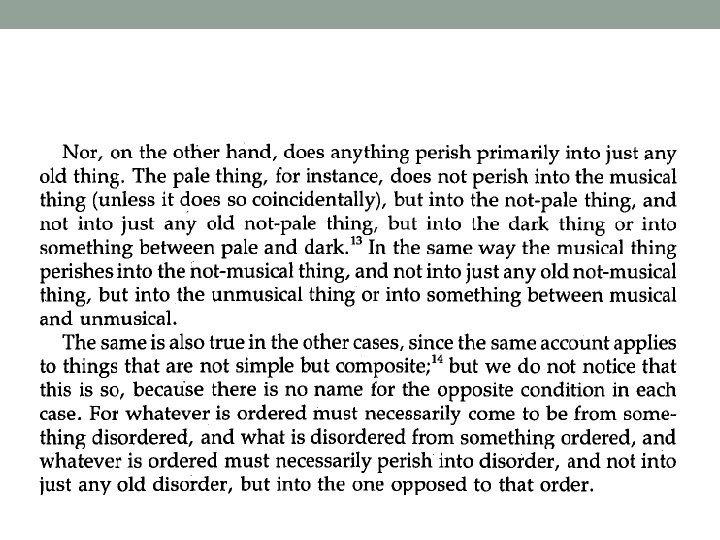

Aristotle’s Physics 1. 5

- Slides: 21