INTIMATE INQUIRY FOR REFLECTIVE PRACTICE AND ACTION RESEARCH

- Slides: 21

INTIMATE INQUIRY FOR REFLECTIVE PRACTICE AND ACTION RESEARCH & AUTOETHNOGRAPHY Maria Lisak Day of Reflection 2019 KOTESOL Reflective Practice SIG

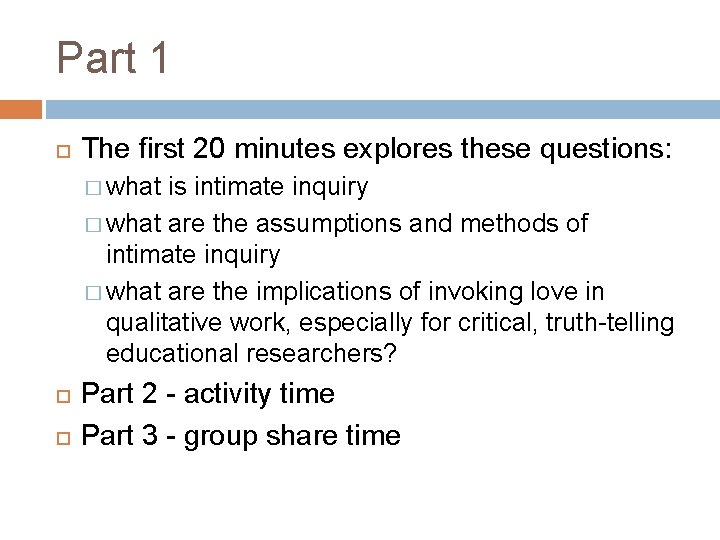

Part 1 The first 20 minutes explores these questions: � what is intimate inquiry � what are the assumptions and methods of intimate inquiry � what are the implications of invoking love in qualitative work, especially for critical, truth-telling educational researchers? Part 2 - activity time Part 3 - group share time

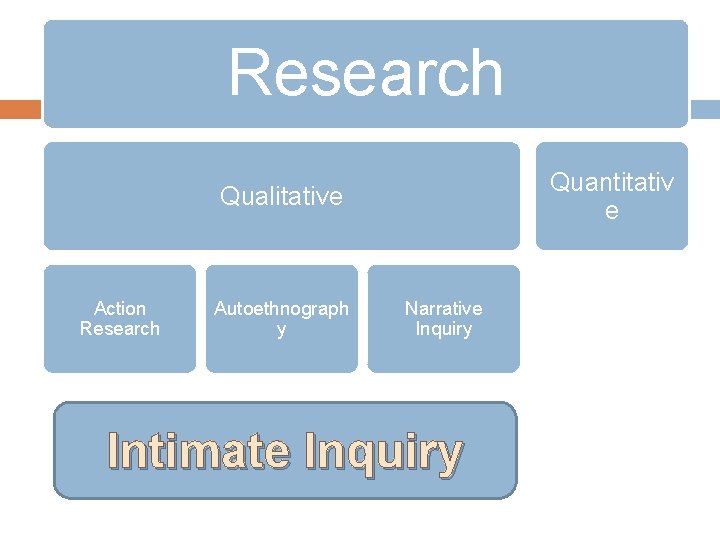

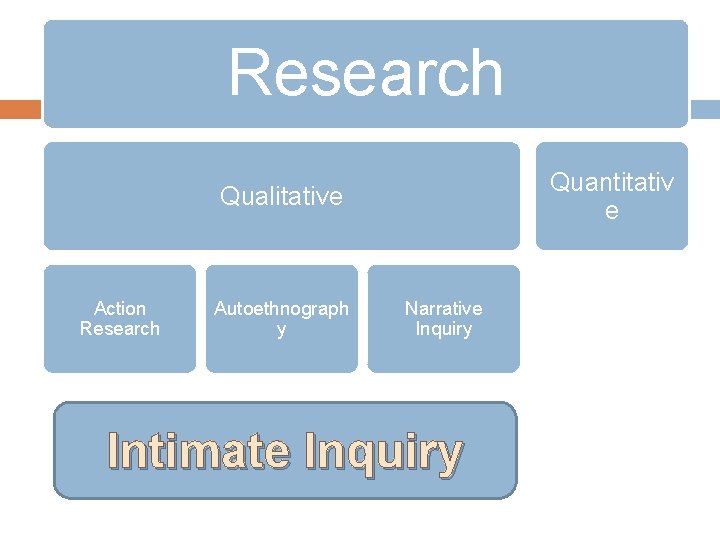

Research Quantitativ e Qualitative Action Research Autoethnograph y Narrative Inquiry Intimate Inquiry

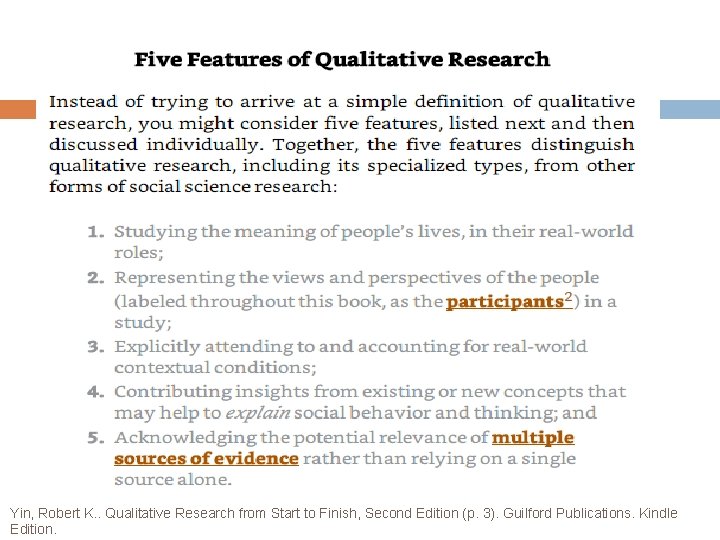

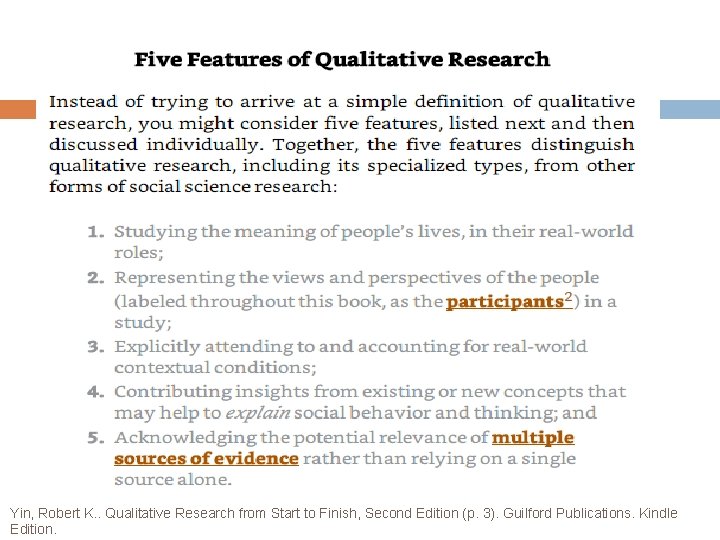

Yin, Robert K. . Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, Second Edition (p. 3). Guilford Publications. Kindle Edition.

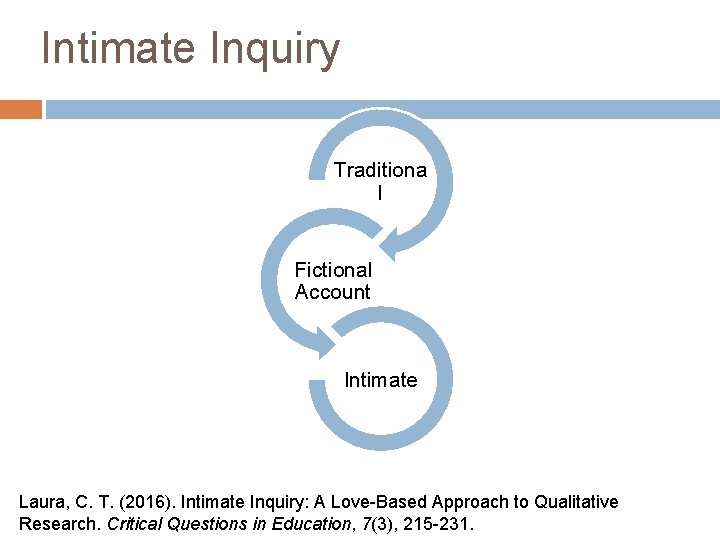

Intimate Inquiry Traditiona l Fictional Account Intimate Laura, C. T. (2016). Intimate Inquiry: A Love-Based Approach to Qualitative Research. Critical Questions in Education, 7(3), 215 -231.

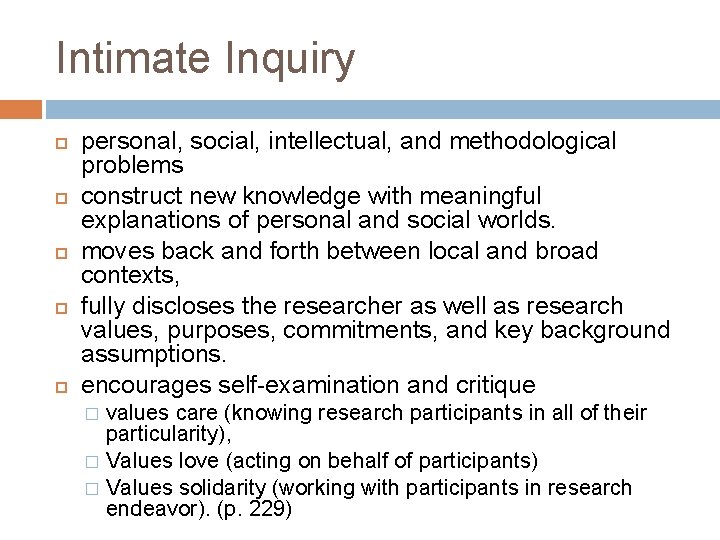

Intimate Inquiry personal, social, intellectual, and methodological problems construct new knowledge with meaningful explanations of personal and social worlds. moves back and forth between local and broad contexts, fully discloses the researcher as well as research values, purposes, commitments, and key background assumptions. encourages self-examination and critique values care (knowing research participants in all of their particularity), � Values love (acting on behalf of participants) � Values solidarity (working with participants in research endeavor). (p. 229) �

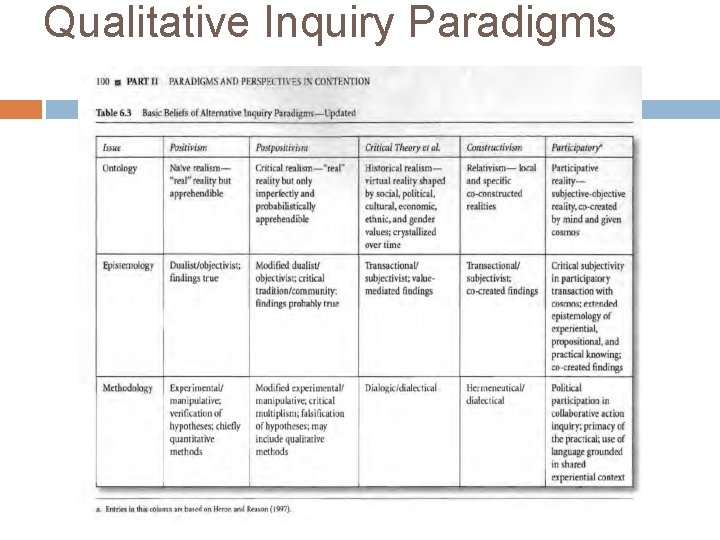

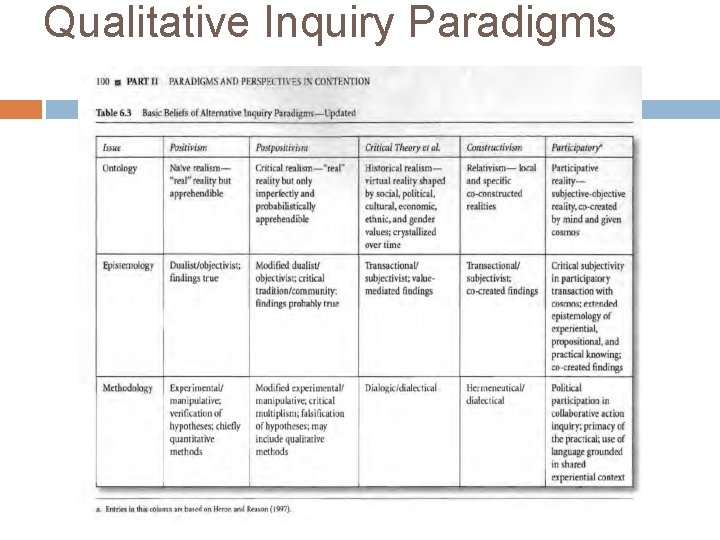

Qualitative Inquiry Paradigms

Part 2 Activity time 1. Inquiry Question; emoji; senses 2. Body Language; observation & analysis 3. Unlearning Privilege 4. Writing a Family Story 5. Interpreting a text/artifact

An Inquiry Question Write on the paper a question you have about your teaching practice. Flip the paper over. � Draw an emoji of your feelings about this question. Think of the senses and write or draw them around the emoticon.

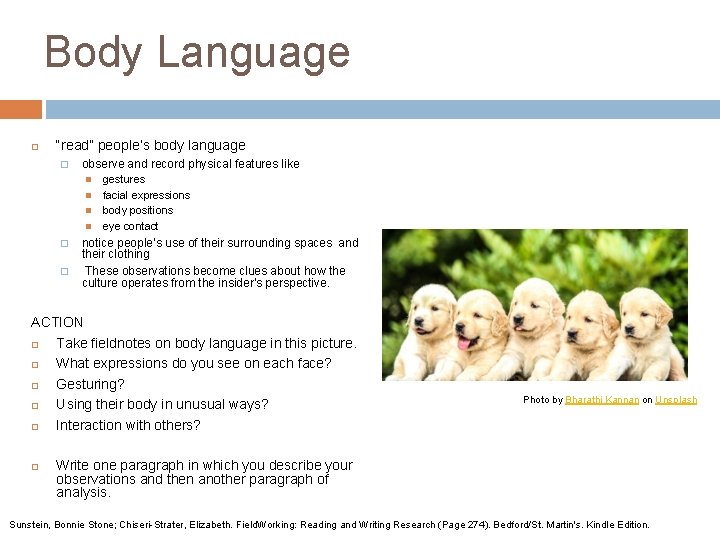

Body Language “read” people’s body language � observe and record physical features like � � gestures facial expressions body positions eye contact notice people’s use of their surrounding spaces and their clothing These observations become clues about how the culture operates from the insider’s perspective. ACTION Take fieldnotes on body language in this picture. What expressions do you see on each face? Gesturing? Using their body in unusual ways? Interaction with others? Photo by Bharathi Kannan on Unsplash Write one paragraph in which you describe your observations and then another paragraph of analysis. Sunstein, Bonnie Stone; Chiseri-Strater, Elizabeth. Field. Working: Reading and Writing Research (Page 274). Bedford/St. Martin's. Kindle Edition.

Unlearning Privilege PURPOSE To discover and reflect on the forces of privilege and power that position you as researcher and your participants as co-researchers in your research. ACTION Make a list of all the privileges you have. Include those that you enjoy through your own efforts (for example, an educational scholarship that you have thanks to your hard work and good grades). Also include privileges that require no effort on your part. ●Age ●Nationality ●Gender ●Skin color, race, or ethnicity ●Education level or opportunities ●Social and/or financial support ●Freedom of religion or of speech or freedom to travel ●Socioeconomic status By thinking about your own privileges, you will think about the privilege and power that your participants possess—or don’t. How might these privileges affect your research? Sunstein, Bonnie Stone; Chiseri-Strater, Elizabeth. Field. Working: Reading and Writing Research (Page 117). Bedford/St. Martin's. Kindle Edition. (from MIMI HARVEY, SHORELINE COMMUNITY COLLEGE, SEATTLE, WASHINGTON)

Writing a Family Story ACTION Recall a family story you’ve heard many times. It may fall into one of these categories: fortunes gained and lost, heroes, “black sheep, ” eccentric or oddball relatives, acts of retribution and revenge, or family feuds. After writing the story, analyze its meaning. When is this story most often told, and why? What kinds of warnings or messages does this story convey? For the family? For an outsider? What kind of lesson does the story teach? How does your story reflect your family’s values? How has it changed or altered through various retellings? Which family members would have different versions? Sunstein, Bonnie Stone; Chiseri-Strater, Elizabeth. Field. Working: Reading and Writing Research (Page 250). Bedford/St. Martin's. Kindle Edition.

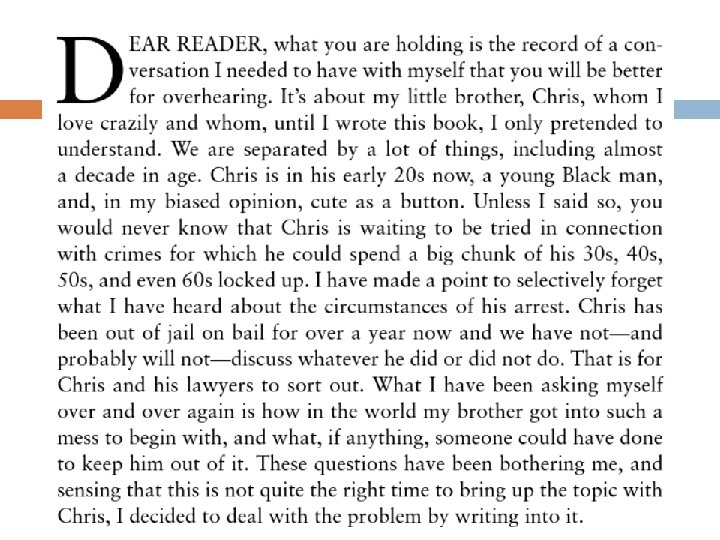

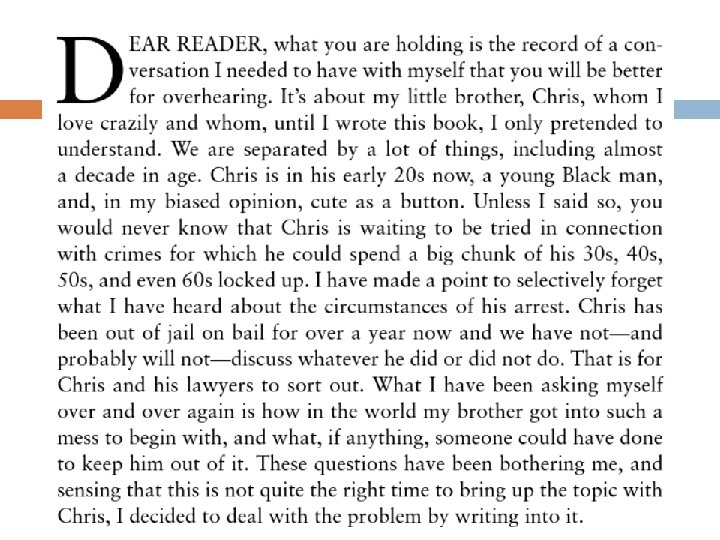

Respond to a Text or Artifact Individually As a Group From descriptions to Interpreting significance What Meaning Making happened alone and together?

Generalizability, Situated Research & Participant Meaning Making Process To me 'situated' means the situation of the participant as understood by the participant, not by external forces such as the researcher, the underwriter of the research, or any presumed 'society' lens. By trying to 'walk in the shoes' of the participants, the researcher is required to have much more of the 'crystal' approach to research - having many facets, layers, and changing depending how external 'light' hits it. I think the quote from Richardson, 1997, p. 92 in LLG 2011 is much more eloquant than my brief mention here. I think that her discussion as described in LLG 2011 of problematizing reliability, validity, and truth as a "transgressive" form of the crystalline seeks to honor the situatedness of the participant by continuously holding up a mirror as a reality check to inherited systems and paradigms that hold reliability, validity, and truth as unchanging and more important to civilization than an individual participant's experience that may or may not bring down, challenge or show the imbalance of power of those very systems. Goodness, am I making any sense? It does to me. I think we need to continuously strive to focus on the participants' meaning-making process even if we, as researchers, find ourselves challenging powerful systems that may well be paying our paychecks. We do not service the participants by morphing their experience to fit pre-existing systems just because we are afraid, lack words to generalize our findings to help others understand the participants' experience, or find it simply more convenient or easier to present findings that may well not be as generalizable as we were hoping. Because of these problems, I like the constructivist and participatory frameworks. Both let the researcher coconstruct with the participants; it does not hold the view that we can be objective and external to our research. From the get-go, simply because we choose to study a particular topic and people, we are constructing. We are already changing and creating something other than the participants' own experience. Therefore we need to include the participant in the research so our lens does not overwrite the participants' intended meaning making. I think the participatory paradigm leaves space to disclose all the nonlinear, overlapping, wildly organic movement that occurs in the lab of reality, that the lab of positivism tries to ignore or control. This paradigm seems very nonscientific, untrustworthy even, yet I think it has story-telling elements that are more truthful because we are not seeking the consensus of quantitative models or even honoring the importance or relevance of generalizability. We live on a planet of infinite variety, we should therefore develop perspectives and research that are just as varied. I mentioned earlier in this post that generalizability can be important when thinking about using limited resources to provide information. Yet research does not have to serve generalizability. Research should help to show and explain many different ways of knowing and being, not just one. References Lincoln, Y. S. , Lynham, S. A. , & Guba, E. G. , (2011). "Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited, Chapter 6. " In Denzin, N. K. , & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds. ). The Sage handbook of qualitative

Position as a Researcher "Context is king" is one of the notes I wrote in my little journal after I started our Yin reading. Last semester I read Toxic Literacies by Dennie Taylor who wrote about her observations of marginalized people losing even more power due to their lack of bureaucratic literacy. Moving, depressing stuff, not just because of the incredibly unfair things happening to her participants in her study, but also from her inclusion of statements from courts, judges, health officials and how powerful their words were to 'write' the reality of the participants. These officials believed they understood the societal context, yet they really had no idea of what reality was actually playing out for these participants. I think qualitative research in the category of context or place is so important. If we are constructing knowledge, are we simply describing the context? Or are we explaining how we are interpreting context to help to communicate to our future selves as well as others where we were in our process and knowledge when we had the experience. I think qualitative research helps us to fight they way our memory 'rewrites' our experience as we continue to process new events and information. Qual research gives us a 'window' on the 'moment in time' that we may well have forgotten or dismissed as new info emerges. For instance, you likely noted that Denzin and Lincoln (2011) position qualitative research as being an interpretative, critical endeavor and call for social science to be “committed up front to issues of social justice” (p. 11). In contrast, Yin (2016) argues for a “pragmatist” approach to qualitative research. As noted in the readings, one's disciplinary perspective and background certainly shapes how one comes to define qualitative research. Indeed, there are multiple positions from which to work within qualitative research and different ways to describe what "it" is. Thus, prior to embarking on a study of qualitative research – and carrying out a qualitative research study – it is important to clarify our own perspectives on the meaning(s) of qualitative research. Thus, with your colleagues, please consider and discuss one or more of the following questions: From your perspective, what is qualitative research? How does your discipline/field define and make sense of qualitative research? What are some of the common characteristics of qualitative research?

Part 3 Group Share time

Thank you! Website for materials: https: //koreamaria. typepad. com/gwangju/2019 /08/intimate-inquiry-workshop-. html

https: //search. proquest. com/docvie w/1803309382? pqorigsite=gscholar

Action Research Reason, P. (2003). Action research and the single case: A response to Bjørn Gustavsen and Davydd Greenwood. Concepts and Transformation, 8(3), 281 -294. While welcoming Gustavsen’s exploration of issues of scale and wider influence in action research, which argues that we need to extend the relatively small scale of individual action research ‘cases’ and see action research as creating social movements and social capital, this article takes issue with the implication that this implies that less attention must be paid to the personal and interpersonal dimensions of action research. Issues of scale must be approached not only through distributive action research as Gustavsen advocates, but also by expanding the emancipatory inquiry space of face-to-face inquiry practices. The integration of the personal with the political is seen as absolutely central to this type of work; a range of examples is offered. The possibility that action research can never be part of mainstream science but rather runs fundamentally counter to mainstream Western culture is explored. It is argued that action research must be seen not as a form of social science producing knowledge or cases, but as a form of day to day inquiry integrated in the lives of individuals, small groups, organizations and society as a whole.

Additional example of intimate inquiry studies in Asian classrooms https: //nsuworks. nova. edu/cgi/viewcontent. cgi ? referer=https: //scholar. google. co. kr/&httpsred ir=1&article=1088&context=tqr/