Interpreting Patterns of Sounds How as stylicians we

![Example the boy kicks(t) the ball on the field Participant [1] Process Participant [2] Example the boy kicks(t) the ball on the field Participant [1] Process Participant [2]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/2f50db8b0eaa63c86212b8d01eae6286/image-23.jpg)

![a) Active Voice the boy saw Participant[1] Process Subject Predicator b) Passive Voice the a) Active Voice the boy saw Participant[1] Process Subject Predicator b) Passive Voice the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/2f50db8b0eaa63c86212b8d01eae6286/image-28.jpg)

- Slides: 33

Interpreting Patterns of Sounds

How, as stylicians, we make connections between the physical properties of the sounds represented within a text and the non – linguistic phenomena situated outside a text to which these sounds are related.

Onomatopoeia A feature of sound patterning which is often thought to form a bridge between ‘style’ and ‘content’. Can be lexical or a nonlexical Both forms share the common property of being able to match up a sound with a nonlinguistic correlate in the ‘real’ world.

Lexical Onomatopoeia Draws upon recognized words in the language system whose pronunciation enacts symbolically their referents outside language. Examples: thud, crack, slurp, buzz

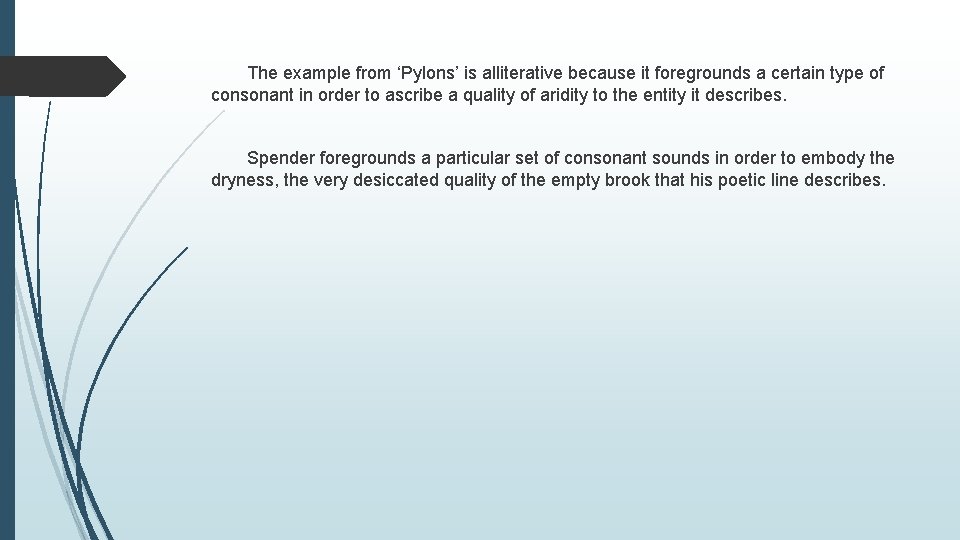

Lexical onomatopoeia plays in the stylistic texture of poetry makes for an important area of study. Examples: Ø [The valley…and the green chestnut…] Are mocked dry like the parched bed of brook. Pylon by Stephen Spender Ø Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here Buckle! […] The Windhover by Gerard Manley Hopkin

The example from ‘Pylons’ is alliterative because it foregrounds a certain type of consonant in order to ascribe a quality of aridity to the entity it describes. Spender foregrounds a particular set of consonant sounds in order to embody the dryness, the very desiccated quality of the empty brook that his poetic line describes.

The example from Hopkins represents a different kind of onomatopoeia, built not through consonant harmony but by a kind of vowel ‘disharmony’. Although accents of English vary, an informal approximation of the six relevant vowels would be: oh – eh – aye – oo – uh.

Nonlexical Onomatopoeia Clusters of sounds which echo the world in a more unmediated way, without the intercession of linguistic structure. Lacks a structure to be a part of a language Examples: vroom vroooom, brmmmm

Phonaesthesia Ø The study of the expressiveness of sounds, especially those sounds which are felt to echo their meanings. It is a kind of sustained or extended onomatopoeia.

Mathews (2007, p. 374) also refers to it as sound symbolism and describes it as: the use of specific sounds or features of sounds in a partly systematic relation to meanings or categories of meaning. Generally taken to include: 1. The use of forms traditionally called onomatopoeic…. 2. Partial resemblances in form among words whose meanings are similar: e. g. among slip, or slither, all with initial /sl/. In the second case the correspondence may be partly explicable by the nature of the sounds and meanings involved: e. g. the least sonorous vowel, /i/, is often associated, in the vocabulary and in the minds of speakers, with concepts of smallness.

Mikov (2003, p. 97) points out that the term ‘sound symbolism’ is somewhat inaccurate because according to her ‘the connection between sound (or phoneme) and meaning is more motivated, less arbitary, than with symbolism proper’. Leech (1969, p. 98) calls it sound symbolism and observes that in it, the sound ‘enacts the sense rather than merely [echoing] it’.

The Phonaesthetic Fallacy Language functions unproblematically as a direct embodiment of the real world. Something that teachers of language and literature have come to dread when dealing with the interpretation of phonetic features in literary texts (Nash 1986: 130) A failing in much traditional literary criticism that it uses aspects of sounds to evoke directly the meaning of the text: a practice evident in common critical comments like ‘rhythmic enactment’ or ‘appropriate sound – patterning’ (Attridge 1988: 133)

The Phonaesthetic Fallacy 1. Make the assumptions that a particular piece of the language is intended to be performed mimetically. 2. We should never lose sight of the text immediately surrounding the particular feature of style under consideration, the co – text.

Style and Transitivity

‘What is character but the determination of incident? What is incident but the illustration of characters? Henry James

A principal mode of narrative characterization is the transmission of ‘actions and events’. The way character is developed through and by semantic processes and participants roles embodied in narrative discourse.

Style Comprises many literary devices that an author employs to create a distinct feel for a work. These devices include, but are not limited to, point of view, symbolism, tone, imagery, diction, voice, syntax, and the method of narration. A fundamental aspect of fiction, as it is naturally part of every work of prose written. A set of linguistic variants with specific social meanings.

Transitivity normally understood as the grammatical feature which indicates if a verb takes a direct object.

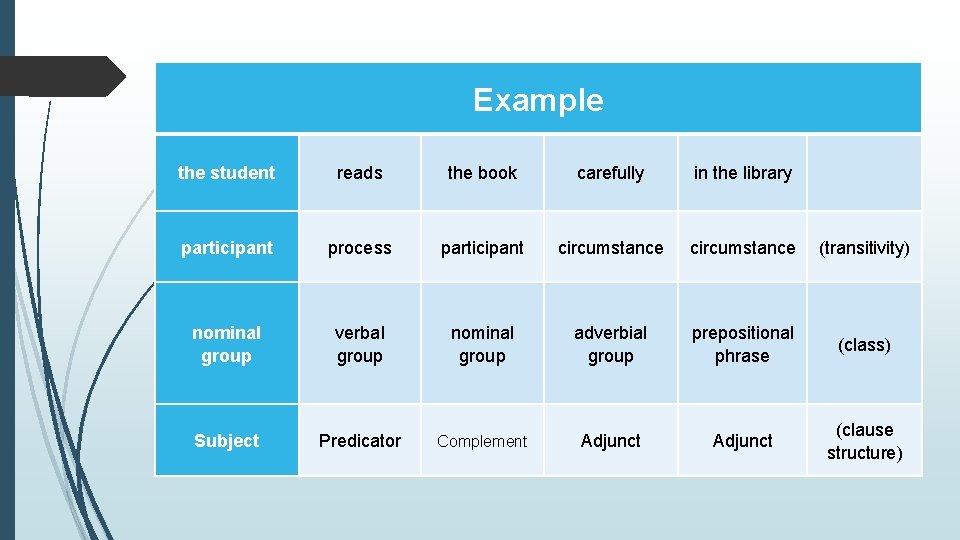

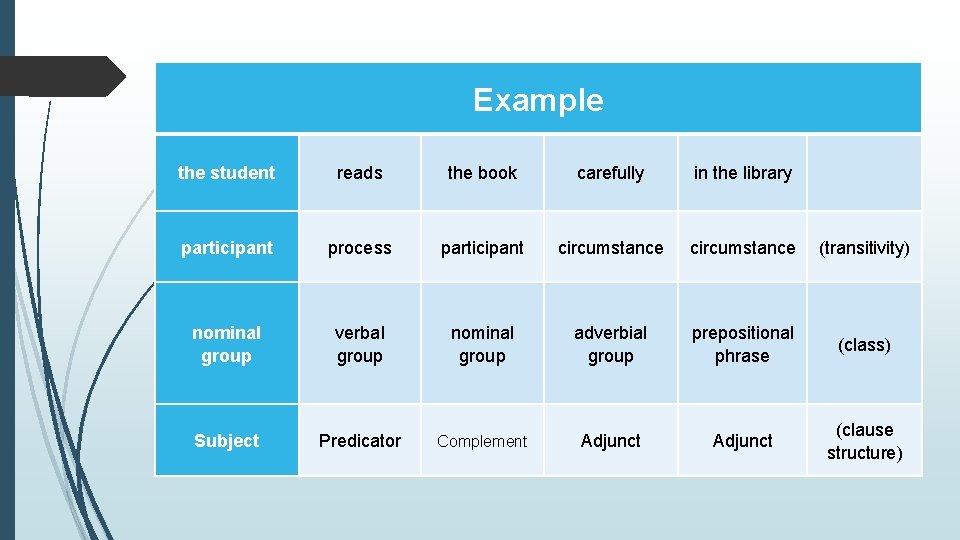

Halliday’s Model of Transitivity There are three components of what Halliday calls a transitivity process: the process itself (ii) participants in the process (iii) circumstances associated with the process The process is realized by a verbal group, the participant(s) by (a) nominal group(s) (although, as noted later, there may be exceptions here), and the circumstance(s) by (an) adverbial group(s) or prepositional phrase(s),

Example the student reads the book carefully in the library participant process participant circumstance (transitivity) nominal group verbal group nominal group adverbial group prepositional phrase (class) Subject Predicator Complement Adjunct (clause structure)

The presence or absence of the complement may in turn determine whethere are one or two participants in the clause, in the sense that (in most cases) if there is no complement, there is one participant, and if there is one complement, there are two participants.

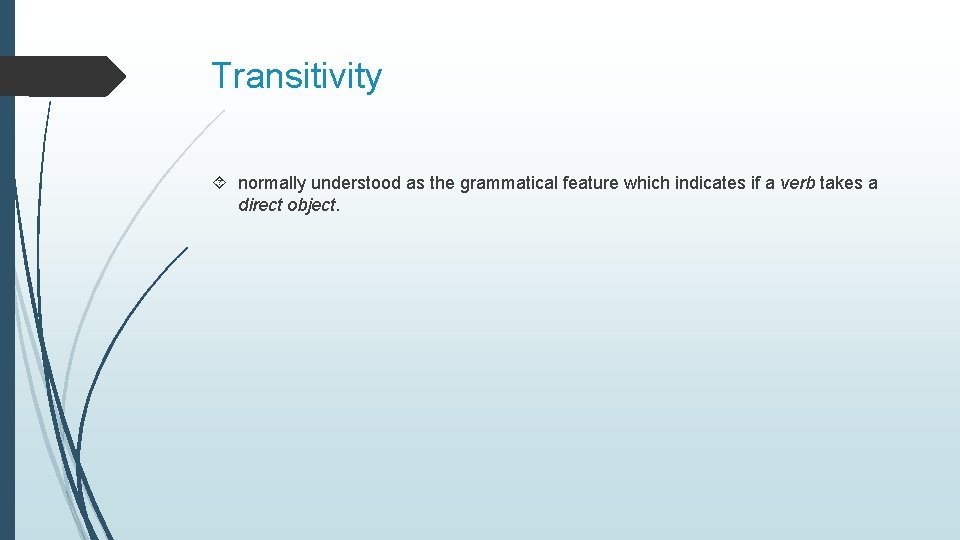

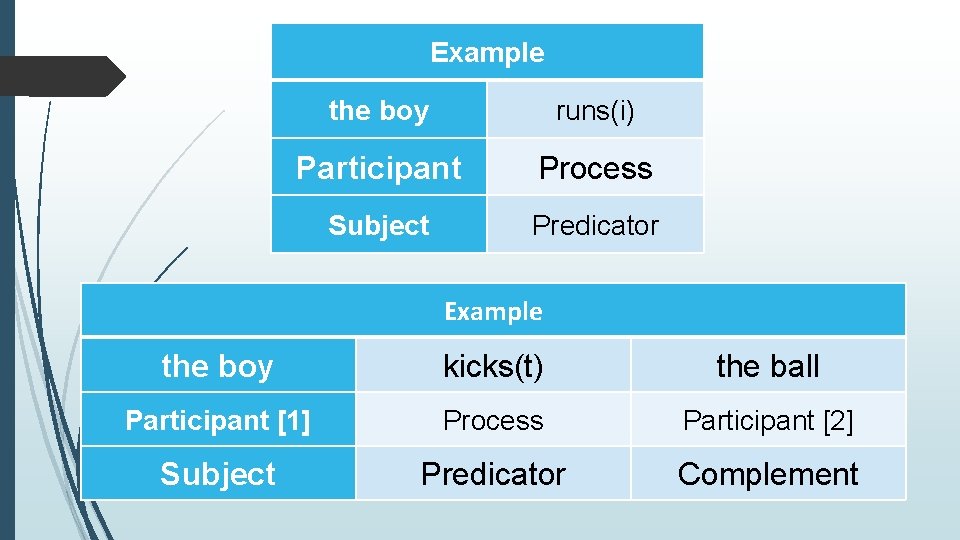

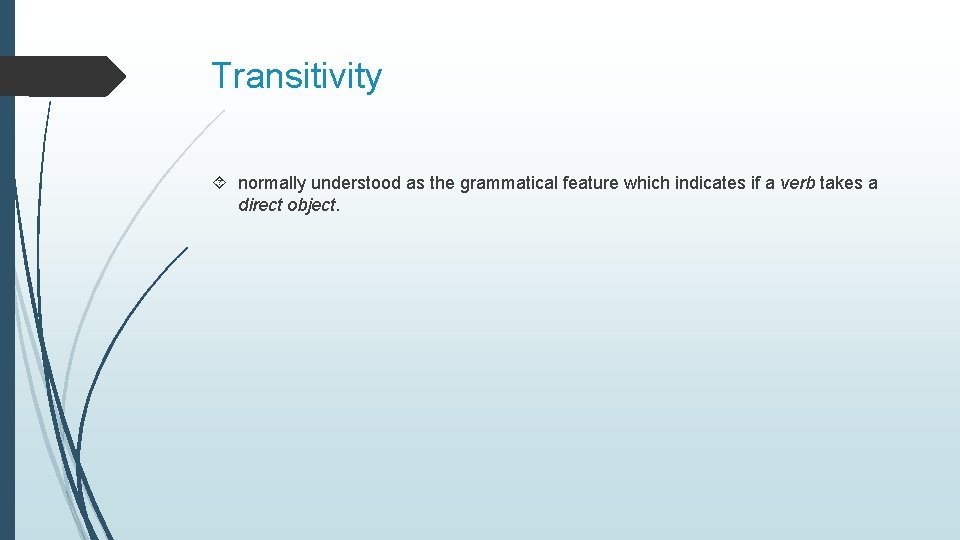

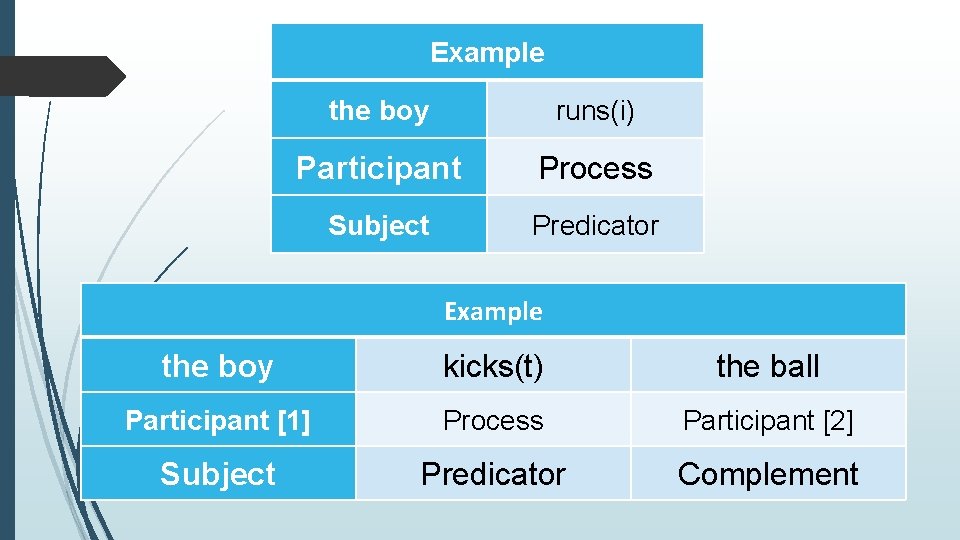

Example the boy runs(i) Participant Process Subject Predicator Example the boy kicks(t) the ball Participant [1] Process Participant [2] Subject Predicator Complement

![Example the boy kickst the ball on the field Participant 1 Process Participant 2 Example the boy kicks(t) the ball on the field Participant [1] Process Participant [2]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/2f50db8b0eaa63c86212b8d01eae6286/image-23.jpg)

Example the boy kicks(t) the ball on the field Participant [1] Process Participant [2] Circumstance Subject Predicator Complement Adjunct

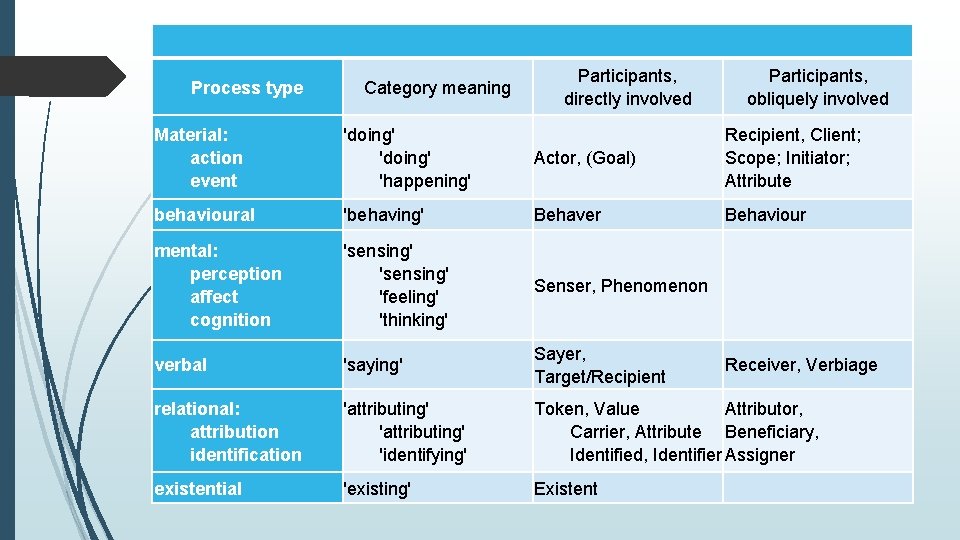

The Six Processes in Halliday's Approach to Transitivity

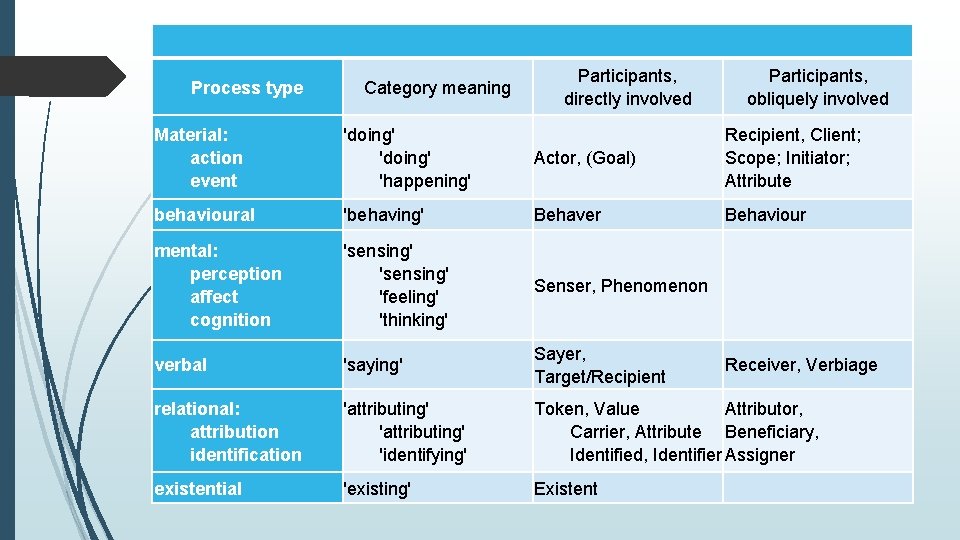

Process type Category meaning Participants, directly involved Participants, obliquely involved Material: action event 'doing' 'happening' Actor, (Goal) Recipient, Client; Scope; Initiator; Attribute behavioural 'behaving' Behaver Behaviour mental: perception affect cognition 'sensing' 'feeling' 'thinking' Senser, Phenomenon verbal 'saying' Sayer, Target/Recipient relational: attribution identification 'attributing' 'identifying' Token, Value Attributor, Carrier, Attribute Beneficiary, Identified, Identifier Assigner existential 'existing' Existent Receiver, Verbiage

Some Notes and Further Observations on the Table One of the things one can notice when one looks at the above table, is the number of (direct) participants involved for each of the processes: Behavioural and existential processes have only one participant each. The other processes may have two. We can also note that the second participants of material and relational processes may or may not be present. We can note two further points: Firstly, the participants are usually represented by nominal groups, and Secondly, processes with single participants make use of intransitive verbs, whilst those with two participants make use of transitive verbs (except for relational processes which make use of intensive verbs).

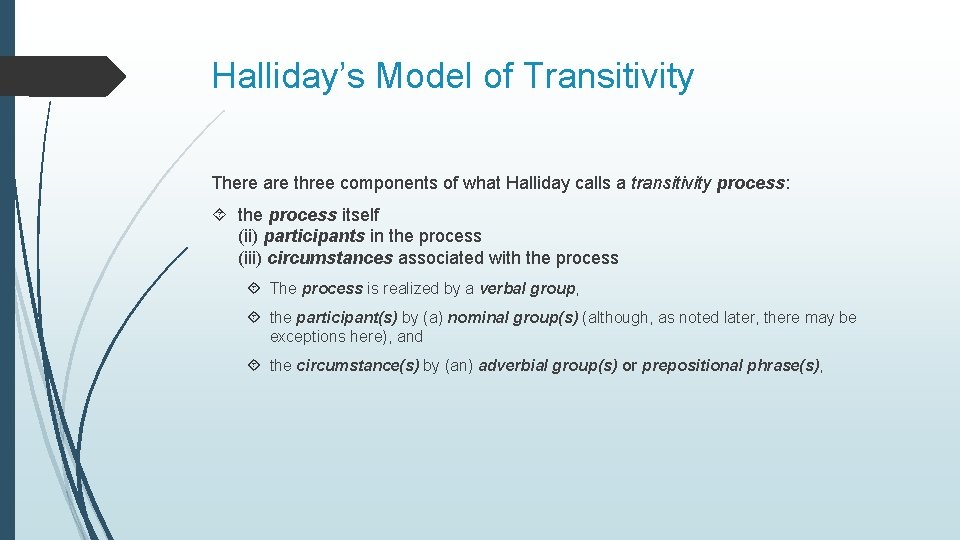

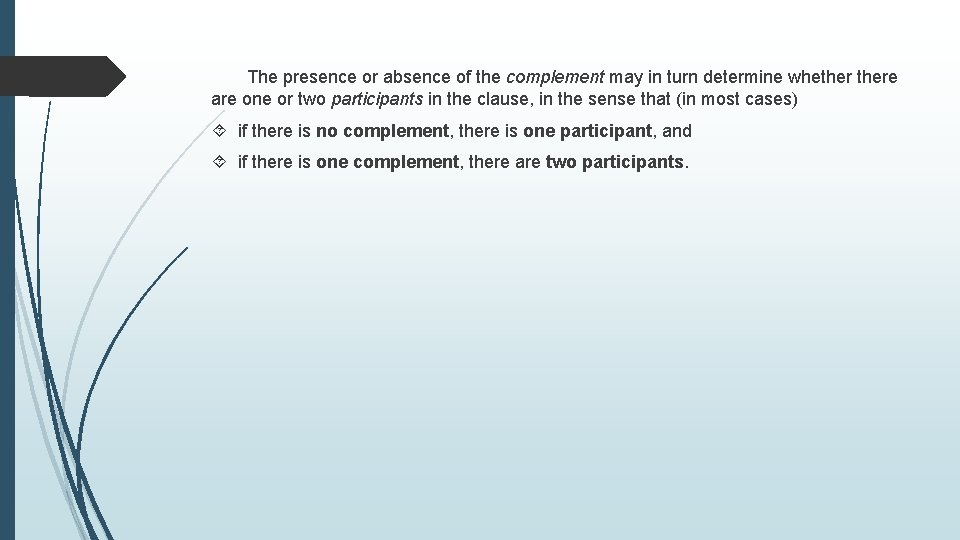

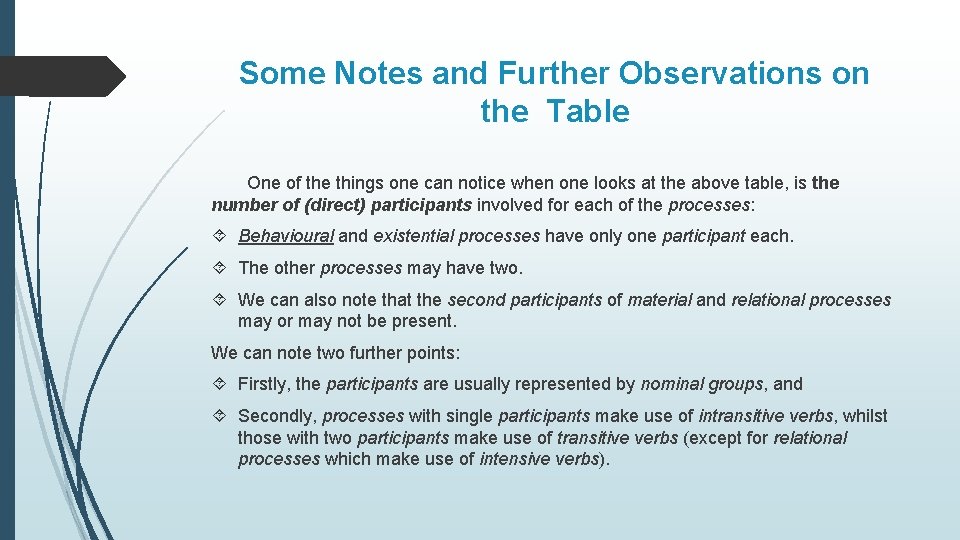

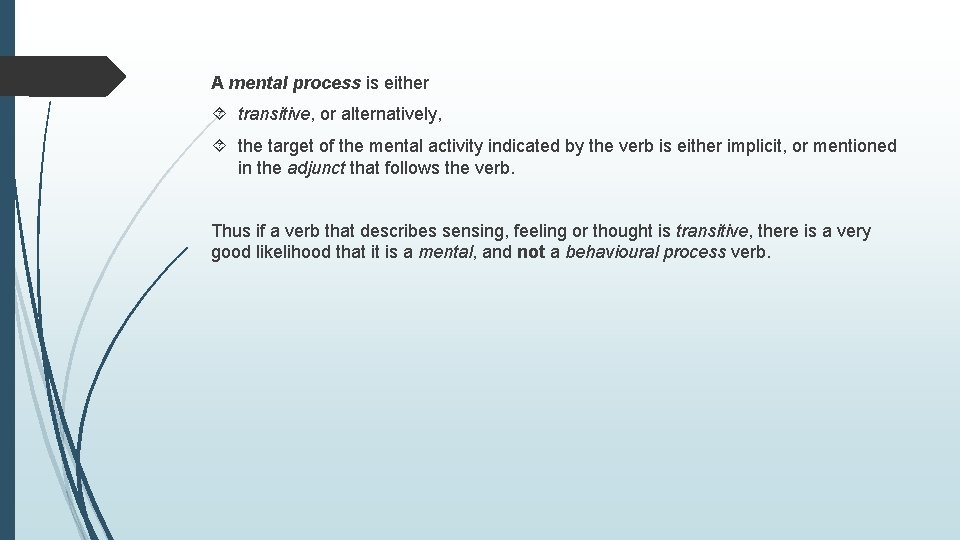

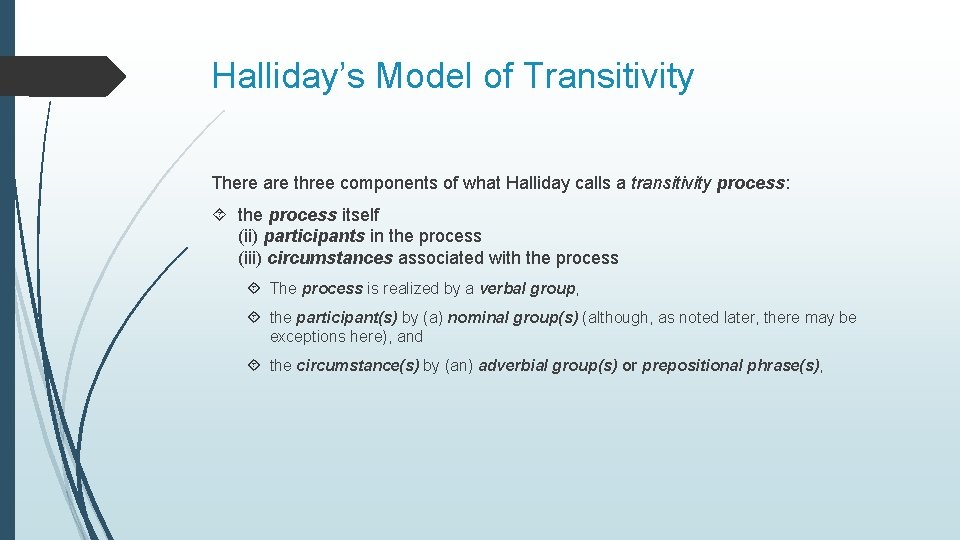

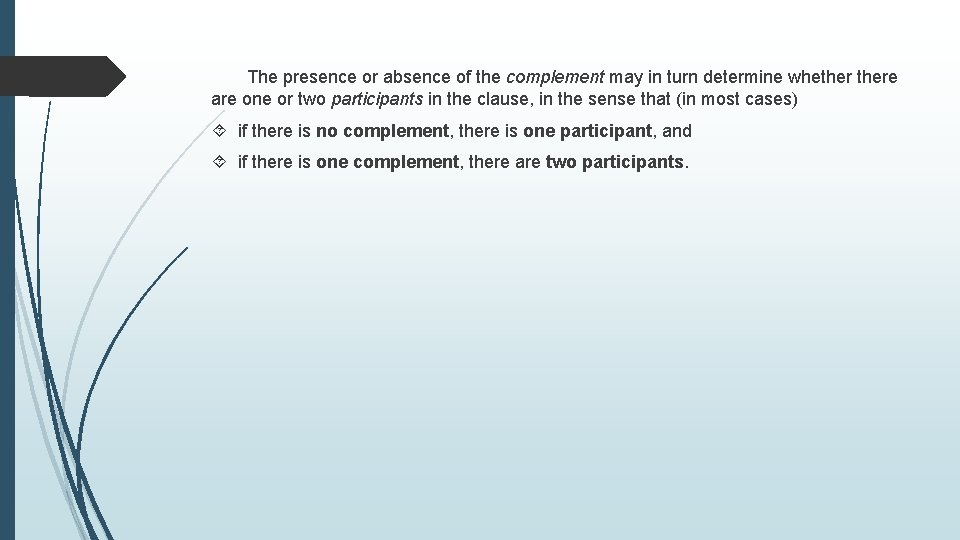

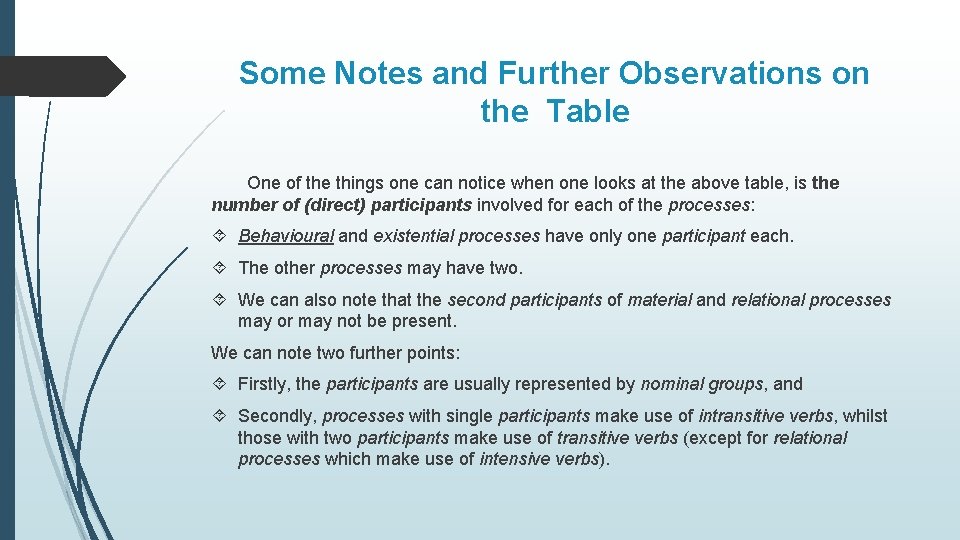

Passivisation and Participant Positions Passivization changes the roles of the participants: the second participant becomes the subject, whilst the first participant becomes the adjunct, as illustrated below. This indicates an important difference between Halliday's conception of the subject in the analysis of mood and modality, and his conception of the actor in transitivity analysis: The actor (or first participant) and subject occur in the same position only in the active voice. In the passive voice, they occur in different positions.

![a Active Voice the boy saw Participant1 Process Subject Predicator b Passive Voice the a) Active Voice the boy saw Participant[1] Process Subject Predicator b) Passive Voice the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/2f50db8b0eaa63c86212b8d01eae6286/image-28.jpg)

a) Active Voice the boy saw Participant[1] Process Subject Predicator b) Passive Voice the ghost Participant[2] Process Complement Subject was seen Predicator by the boy Participant[1] Adjunct The actor or First Participant is realized by the Subject in the active voice and by the Adjunct in the passive voice. The passive voice may also give rise to the stylistically interesting phenomenon of agent deletion, where the actor or First Participant is not indicated, as in the clause 'the ghost has been seen', which does not indicate who has or have seen the ghost.

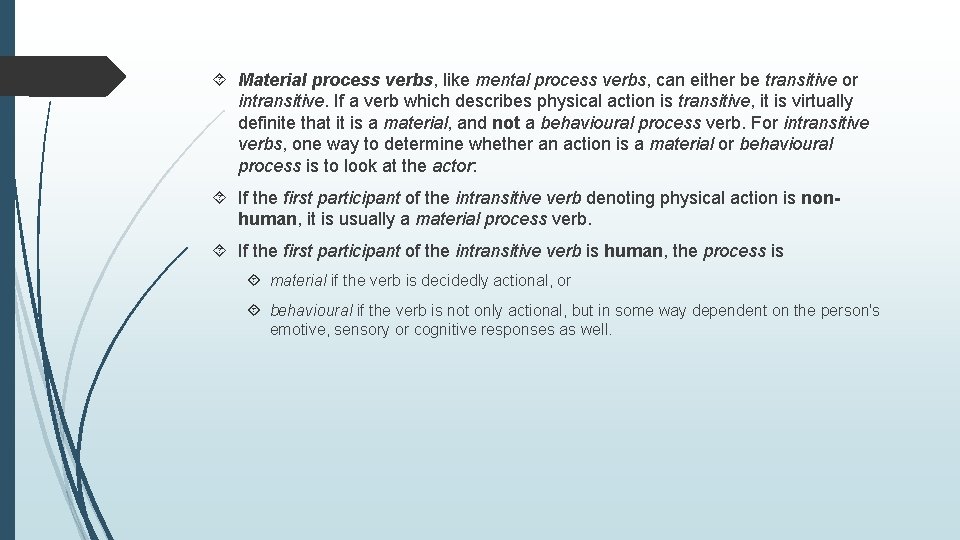

Behavioural processes stand between material and mental processes. Partly as a result of this, some of you may find it difficult to distinguish between behavioural process verbs and material process verbs on the one hand, and between behavioural process verbs and mental process verbs on the other. As a rule of thumb, a behavioural process verb is intransitive (it has only one participant) and indicates an activity in which both the physical and mental aspects are inseparable and indispensable to it.

A mental process is either transitive, or alternatively, the target of the mental activity indicated by the verb is either implicit, or mentioned in the adjunct that follows the verb. Thus if a verb that describes sensing, feeling or thought is transitive, there is a very good likelihood that it is a mental, and not a behavioural process verb.

Material process verbs, like mental process verbs, can either be transitive or intransitive. If a verb which describes physical action is transitive, it is virtually definite that it is a material, and not a behavioural process verb. For intransitive verbs, one way to determine whether an action is a material or behavioural process is to look at the actor: If the first participant of the intransitive verb denoting physical action is nonhuman, it is usually a material process verb. If the first participant of the intransitive verb is human, the process is material if the verb is decidedly actional, or behavioural if the verb is not only actional, but in some way dependent on the person's emotive, sensory or cognitive responses as well.