Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis for Annas project students How

- Slides: 21

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis for Anna’s project students How to analyse your data

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis IPA is a newly developed, and continually developing, methodological tool to analyse meaning-making founded by Jonathan Smith (1997; In N. Hayes Doing Qualitative Research in Psychology) Central concern is with the uniqueness of a person’s experiences how they are made meaningful how these meanings manifest themselves

Phenomenology (Husserl, 1859 -1938) “the study of human experience and the way in which things are perceived as they appear to consciousness” (Landridge, 2007, p 10) challenges notion of absolute truth / reality Does redness mean the same thing to you as it does to me? Critical realist method: reality exists but our access to it is never direct. Also assumes is time and context bound. unit of study in IPA research is the experiential account

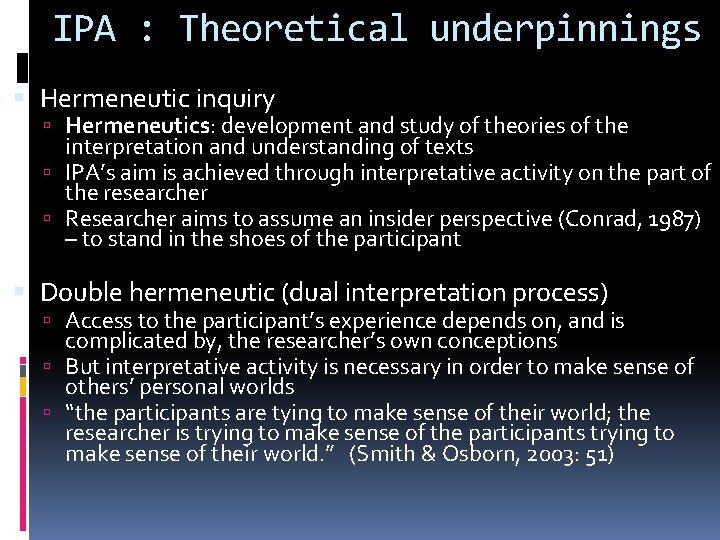

IPA : Theoretical underpinnings Hermeneutic inquiry Hermeneutics: development and study of theories of the interpretation and understanding of texts IPA’s aim is achieved through interpretative activity on the part of the researcher Researcher aims to assume an insider perspective (Conrad, 1987) – to stand in the shoes of the participant Double hermeneutic (dual interpretation process) Access to the participant’s experience depends on, and is complicated by, the researcher’s own conceptions But interpretative activity is necessary in order to make sense of others’ personal worlds “the participants are tying to make sense of their world; the researcher is trying to make sense of the participants trying to make sense of their world. ” (Smith & Osborn, 2003: 51)

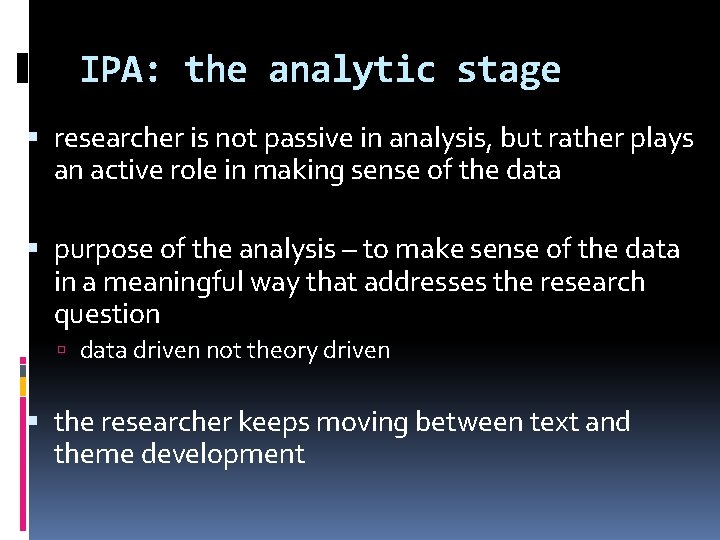

IPA: the analytic stage researcher is not passive in analysis, but rather plays an active role in making sense of the data purpose of the analysis – to make sense of the data in a meaningful way that addresses the research question data driven not theory driven the researcher keeps moving between text and theme development

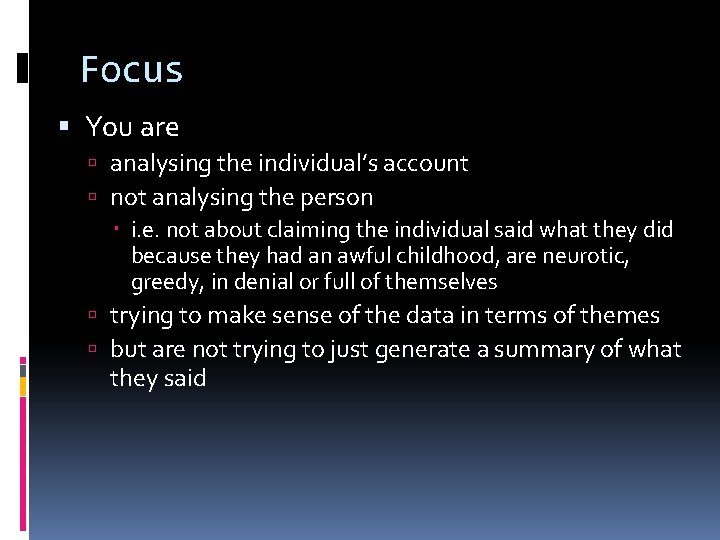

Focus You are analysing the individual’s account not analysing the person i. e. not about claiming the individual said what they did because they had an awful childhood, are neurotic, greedy, in denial or full of themselves trying to make sense of the data in terms of themes but are not trying to just generate a summary of what they said

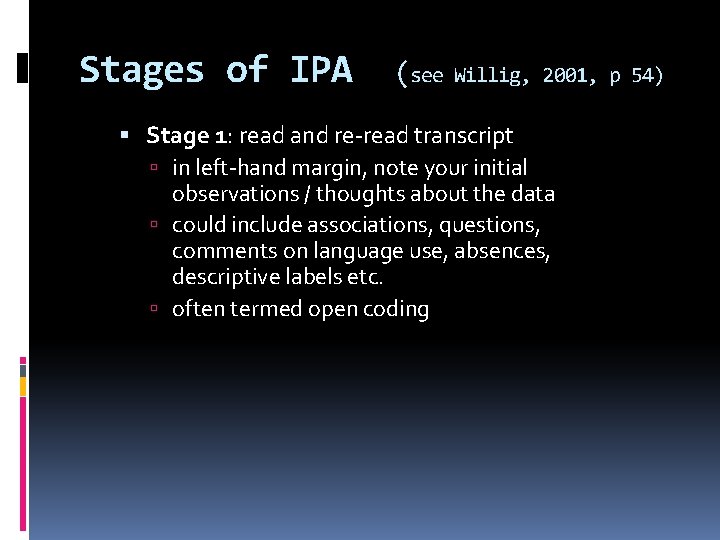

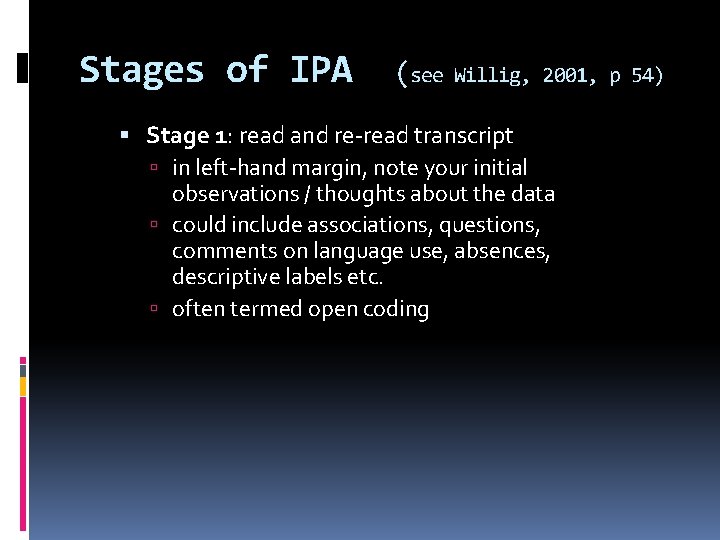

Stages of IPA (see Willig, 2001, p 54) Stage 1: read and re-read transcript in left-hand margin, note your initial observations / thoughts about the data could include associations, questions, comments on language use, absences, descriptive labels etc. often termed open coding

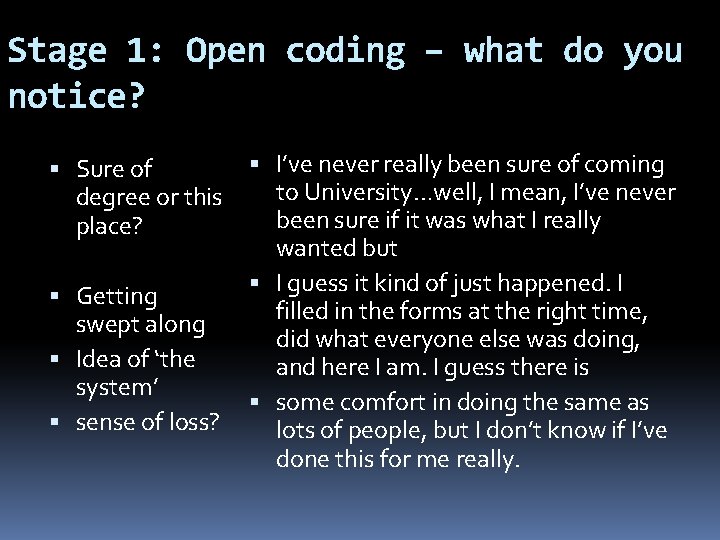

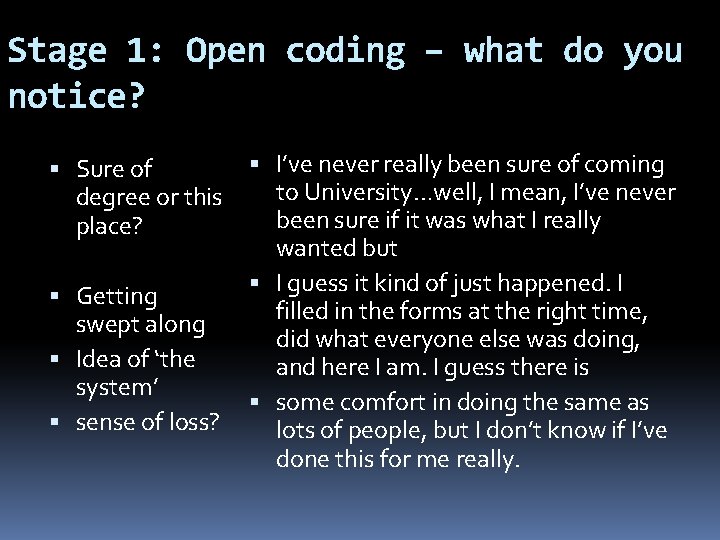

Stage 1: Open coding – what do you notice? Sure of degree or this place? Getting swept along Idea of ‘the system’ sense of loss? I’ve never really been sure of coming to University…well, I mean, I’ve never been sure if it was what I really wanted but I guess it kind of just happened. I filled in the forms at the right time, did what everyone else was doing, and here I am. I guess there is some comfort in doing the same as lots of people, but I don’t know if I’ve done this for me really.

Stages of IPA (see Willig, 2001, p 54) Stage 2: identify and label themes that characterise each section of text these should be conceptual, should capture something about the essential quality of what was said, and you can use psychological terminology to do so

Stage 2: How to be conceptual Move beyond description of the text, or paraphrasing of it. Ask yourself, what is this text referring to? What is the participant really getting at, or really trying to convey? Attempt to capture more concisely the psychological quality inherent in the extract: can use psychological terminology here Caution is essential so that the connection between the participant’s own words and the researcher’s interpretation is not lost.

Refining themes Once you have generated themes across the whole transcript, consider which themes are similar (conceptually) You may decide to omit some themes which no longer seem prominent compared to others Be prepared to keep moving between theme development, text analysis and grouping – you may need to refine this through several cycles.

Stage 3 Introduce structure: relationships between themes look for ways in which themes may be grouped between 2 and 5 themes could meaningfully form a cluster

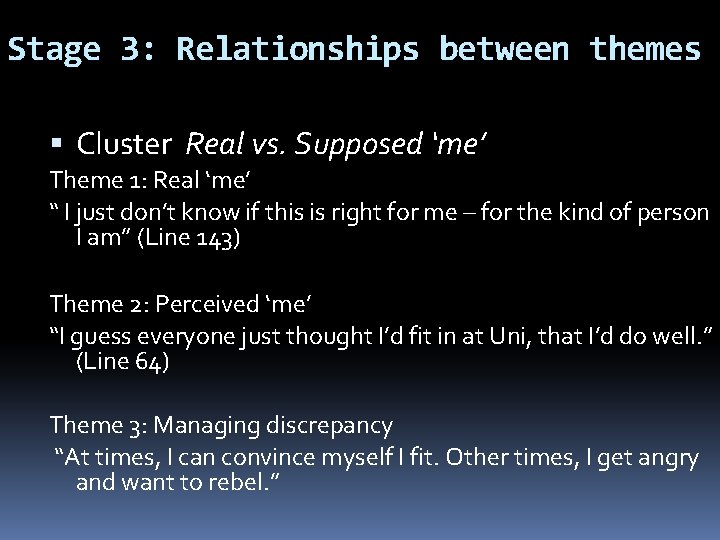

Stage 3: Relationships between themes Cluster Real vs. Supposed ‘me’ Theme 1: Real ‘me’ “ I just don’t know if this is right for me – for the kind of person I am” (Line 143) Theme 2: Perceived ‘me’ “I guess everyone just thought I’d fit in at Uni, that I’d do well. ” (Line 64) Theme 3: Managing discrepancy “At times, I can convince myself I fit. Other times, I get angry and want to rebel. ”

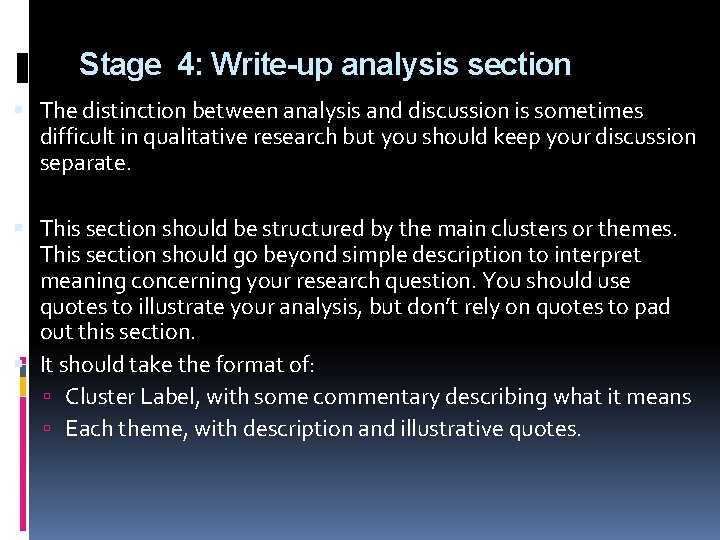

Stage 4: Write-up analysis section The distinction between analysis and discussion is sometimes difficult in qualitative research but you should keep your discussion separate. This section should be structured by the main clusters or themes. This section should go beyond simple description to interpret meaning concerning your research question. You should use quotes to illustrate your analysis, but don’t rely on quotes to pad out this section. It should take the format of: Cluster Label, with some commentary describing what it means Each theme, with description and illustrative quotes.

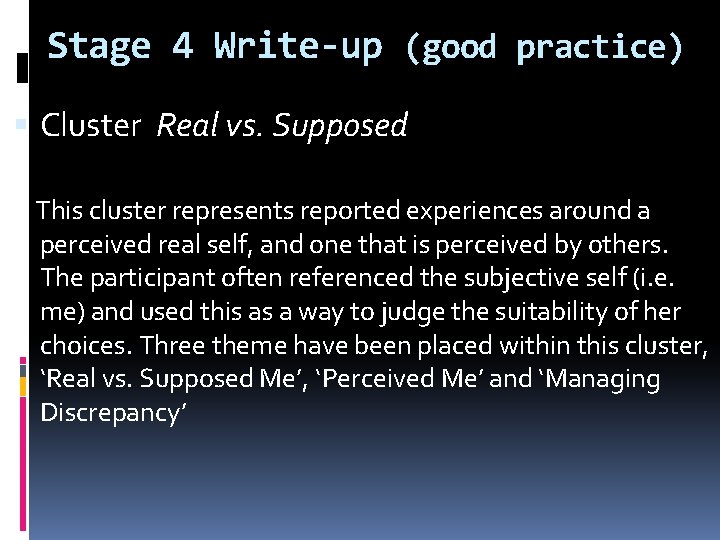

Stage 4 Write-up (good practice) Cluster Real vs. Supposed This cluster represents reported experiences around a perceived real self, and one that is perceived by others. The participant often referenced the subjective self (i. e. me) and used this as a way to judge the suitability of her choices. Three theme have been placed within this cluster, ‘Real vs. Supposed Me’, ‘Perceived Me’ and ‘Managing Discrepancy’

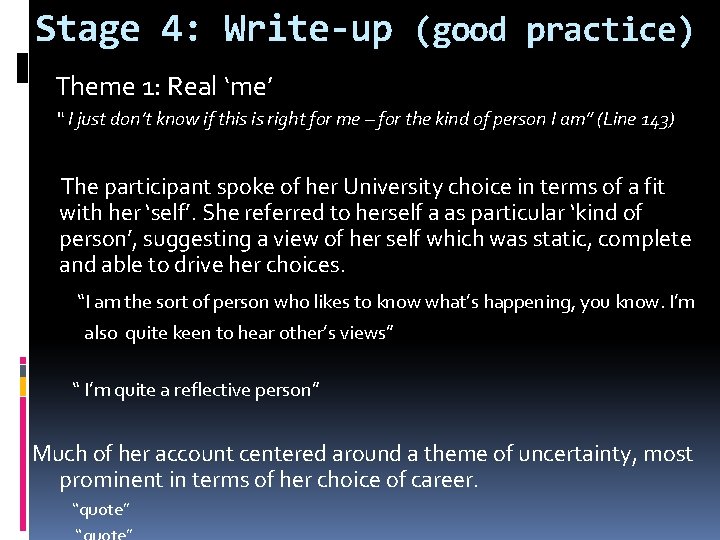

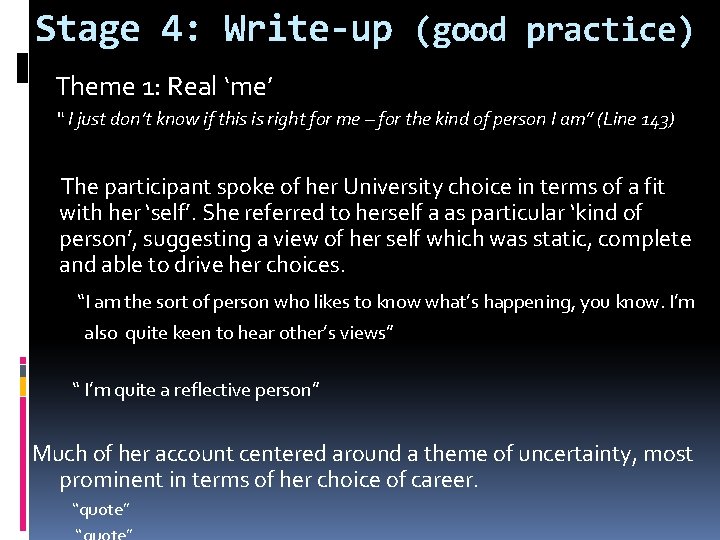

Stage 4: Write-up (good practice) Theme 1: Real ‘me’ “ I just don’t know if this is right for me – for the kind of person I am” (Line 143) The participant spoke of her University choice in terms of a fit with her ‘self’. She referred to herself a as particular ‘kind of person’, suggesting a view of her self which was static, complete and able to drive her choices. “I am the sort of person who likes to know what’s happening, you know. I’m also quite keen to hear other’s views” “ I’m quite a reflective person” Much of her account centered around a theme of uncertainty, most prominent in terms of her choice of career. “quote”

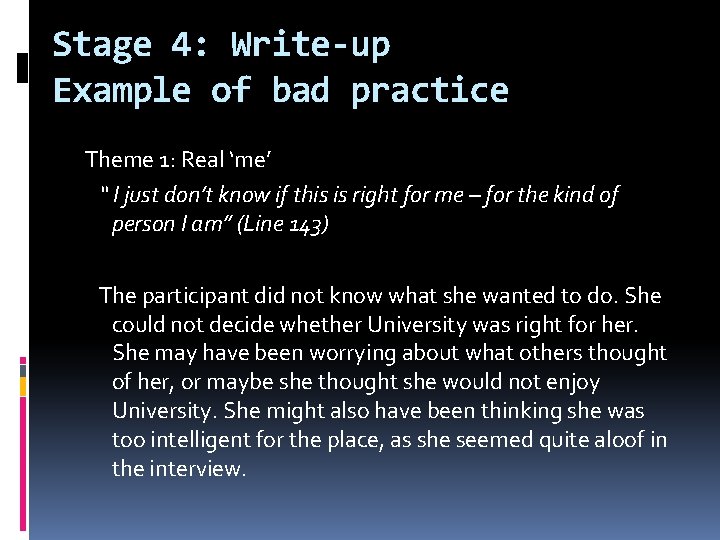

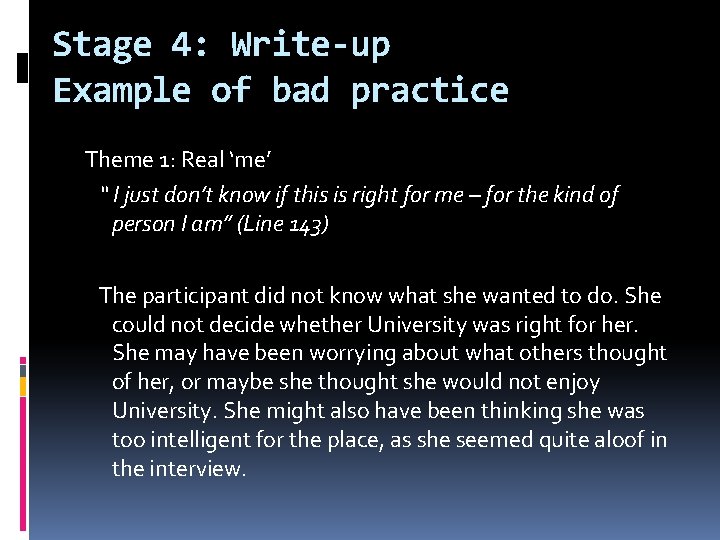

Stage 4: Write-up Example of bad practice Theme 1: Real ‘me’ “ I just don’t know if this is right for me – for the kind of person I am” (Line 143) The participant did not know what she wanted to do. She could not decide whether University was right for her. She may have been worrying about what others thought of her, or maybe she thought she would not enjoy University. She might also have been thinking she was too intelligent for the place, as she seemed quite aloof in the interview.

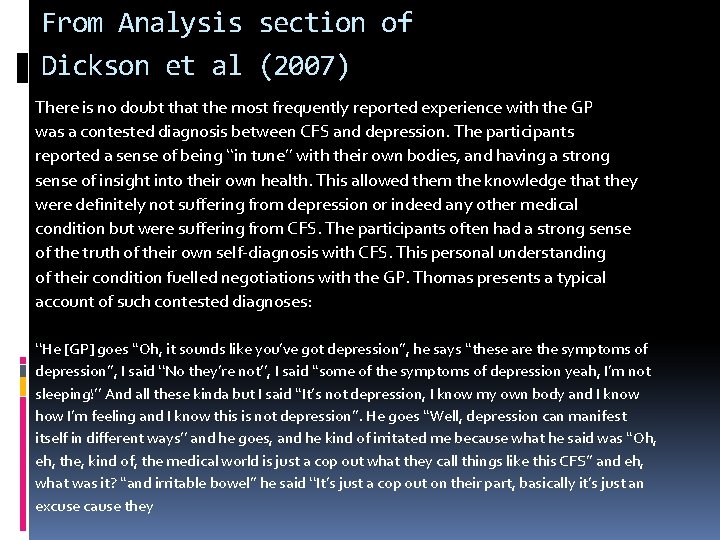

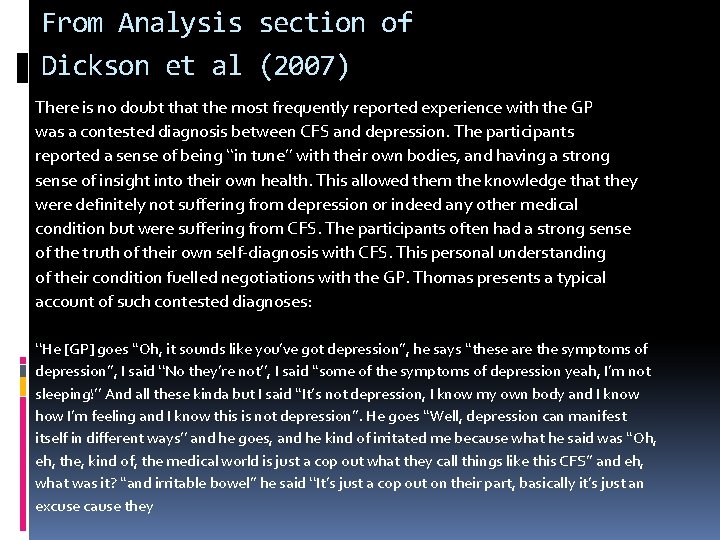

From Analysis section of Dickson et al (2007) There is no doubt that the most frequently reported experience with the GP was a contested diagnosis between CFS and depression. The participants reported a sense of being ‘‘in tune’’ with their own bodies, and having a strong sense of insight into their own health. This allowed them the knowledge that they were definitely not suffering from depression or indeed any other medical condition but were suffering from CFS. The participants often had a strong sense of the truth of their own self-diagnosis with CFS. This personal understanding of their condition fuelled negotiations with the GP. Thomas presents a typical account of such contested diagnoses: ‘‘He [GP] goes ‘‘Oh, it sounds like you’ve got depression’’, he says ‘‘these are the symptoms of depression’’, I said ‘‘No they’re not’’, I said ‘‘some of the symptoms of depression yeah, I’m not sleeping!’’ And all these kinda but I said ‘‘It’s not depression, I know my own body and I know how I’m feeling and I know this is not depression’’. He goes ‘‘Well, depression can manifest itself in different ways’’ and he goes, and he kind of irritated me because what he said was ‘‘Oh, eh, the, kind of, the medical world is just a cop out what they call things like this CFS’’ and eh, what was it? ‘‘and irritable bowel’’ he said ‘‘It’s just a cop out on their part, basically it’s just an excuse cause they

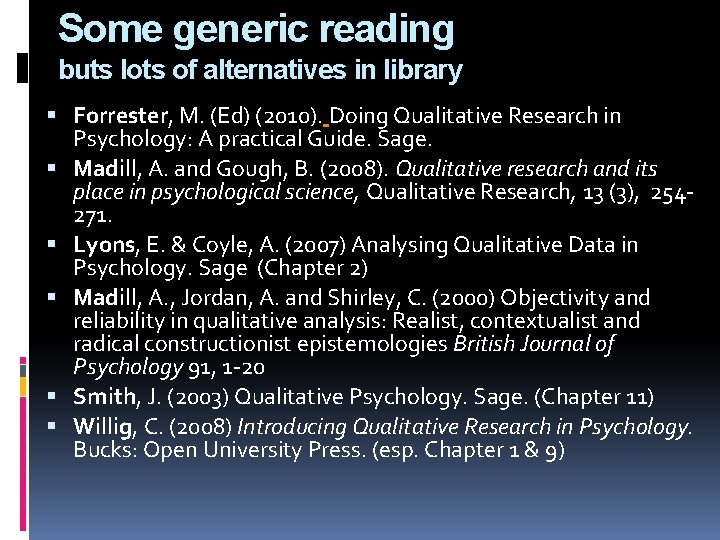

Some generic reading buts lots of alternatives in library Forrester, M. (Ed) (2010). Doing Qualitative Research in Psychology: A practical Guide. Sage. Madill, A. and Gough, B. (2008). Qualitative research and its place in psychological science, Qualitative Research, 13 (3), 254271. Lyons, E. & Coyle, A. (2007) Analysing Qualitative Data in Psychology. Sage (Chapter 2) Madill, A. , Jordan, A. and Shirley, C. (2000) Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies British Journal of Psychology 91, 1 -20 Smith, J. (2003) Qualitative Psychology. Sage. (Chapter 11) Willig, C. (2008) Introducing Qualitative Research in Psychology. Bucks: Open University Press. (esp. Chapter 1 & 9)

Borrowing projects from the Student Support Officer Lydia Bickley Akeisha Brown Hannah Conroy Helen Elliott Chelsea Ennis Molly Forrest Corey Lee Amelia Gardner

Refer also to the ‘Guide to Writing Qualitative Reports and Projects’