Intermediate Level FORMAL FALLACIES FORMAL FALLACIES Click on

- Slides: 20

Intermediate Level FORMAL FALLACIES

FORMAL FALLACIES Click on the image to the left. You will need to be connected to the internet to view this presentation. Enlarge to full screen

Fallacies In logical arguments, fallacies are either formal or informal. 3

Formal Fallacies In philosophy, a formal fallacy is a pattern of reasoning rendered invali d by a flaw in its logical structure that can neatly be expressed in a standard logic system

Formal Fallacies A formal fallacy is contrasted with an informal fallacy, which may have a valid logical form and yet be unsound because one or more premises are false.

Formal Fallacies In philosophy, the term logical fallacy properly refers to a formal fallacy—a flaw in the structure of a deductive argument, which renders the argument invalid.

Formal Fallacy The presence of a formal fallacy in a deductive argument does not imply anything about the argument's premises or its conclusion.

Formal Fallacy Affirming the consequent Any argument that takes the following form is a non sequitur If A is true, then B is true. Therefore, A is true. An example of affirming the consequent would be: If Jackson is a human (A), then Jackson is a mammal. (B) Therefore, Jackson is a human. (A)

Formal Fallacy While the conclusion may be true, it does not follow from the premise: Humans are mammals Jackson is a mammal Therefore, human Jackson is a Affirming the consequent is essentially the same as the fallacy of the undistributed middle, but using propositions rather than set membership.

Formal Fallacy Denying the antecedent Another common non sequitur is this: If A is true, then B is true. A is false. Therefore, B is false.

Formal Fallacy An example of denying the antecedent would be: • If I am Japanese, then • I am Asian. • I am not Japanese. Therefore, • I am not Asian. While B can indeed be false, this cannot be linked to the premise since the statement is a non sequitur. This is called denying the antecedent.

Formal Fallacy In contrast to informal fallacy Formal logic is not used to determine whether or not an argument is true. Formal arguments can either be valid or invalid. A valid argument may also be sound or unsound. A valid argument has a correct formal structure. -A valid argument is one where if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. -A sound argument is a formally correct argument that also contains true premises.

Formal Fallacy Formal fallacies do not take into account the soundness of an argument, but rather its validity. As modus ponens, the following argument contains no formal fallacies: If P then Q P Therefore Q

Formal Fallacy A logical fallacy associated with this format of argument is referred to as affirming the consequent, which would look like this: If P then Q Q Therefore P

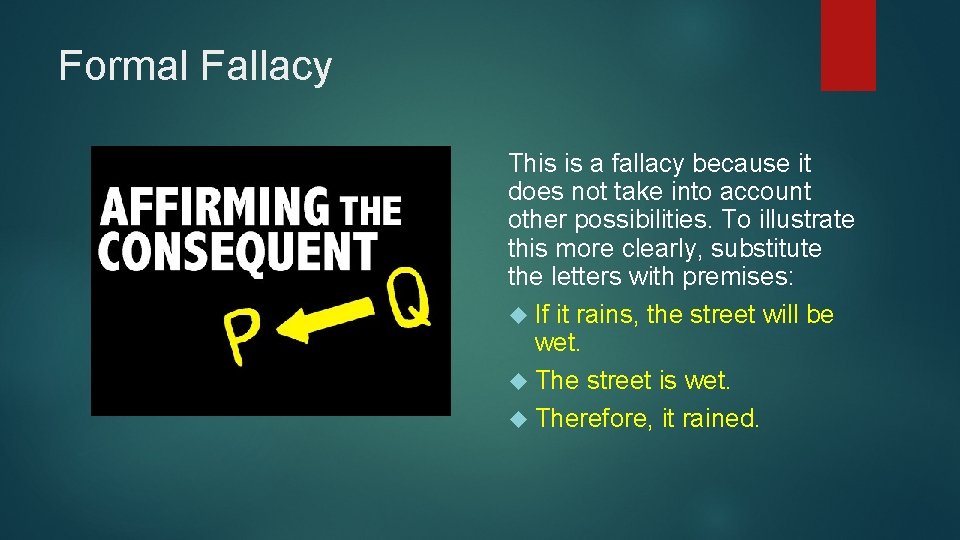

Formal Fallacy This is a fallacy because it does not take into account other possibilities. To illustrate this more clearly, substitute the letters with premises: If it rains, the street will be wet. The street is wet. Therefore, it rained.

FORMAL FALLACIES Although it is possible that this conclusion is true, it does not necessarily mean it must be true. The street could be wet for a variety of other reasons that this argument does not take into account. However, if we look at the valid form of the argument, we can see that the conclusion must be true: If it rains, the street will be wet. It rained. Therefore, the street is wet.

FORMAL FALLACIES If statements 1 and 2 are true, it absolutely follows that statement 3 is true. However, it may still be the case that statement 1 or 2 is not true. For example: If Albert Einstein makes a statement about science, it is correct. Albert Einstein states that all quantum mechanics is deterministic. Therefore, it's true that quantum mechanics is deterministic.

FORMAL FALLACIES By contrast, an argument with a formal fallacy could still contain all true premises: If someone owns Fort Knox, then he is rich. Bill Gates is rich. Therefore, Bill Gates owns Fort Knox. Though, 1 and 2 are true statements, 3 does not follow because the argument commits the formal fallacy of affirming the consequent

FORMAL FALLACIES An argument could contain both an informal fallacy and a formal fallacy yet lead to a conclusion that happens to be true, for example, again affirming the consequent, now also from an untrue premise: If a scientist makes a statement about science, it is correct. It is true that quantum mechanics is deterministic. Therefore, a scientist has made a statement about it.

Bibliography Aristotle, On Sophistical Refutations, De Sophistici Elenchi. William of Ockham, Summa of Logic (ca. 1323) Part III. 4. John Buridan, Summulae de dialectica Book VII. Francis Bacon, the doctrine of the idols in Novum Organum Scientiarum, Aphorisms concerning The Interpretation of Nature and the Kingdom of Man, XXIIIff. The Art of Controversy | Die Kunst, Recht zu behalten – The Art Of Controversy (bilingual), by Arthur Schopenhauer John Stuart Mill, A System of Logic – Raciocinative and Inductive. Book 5, Chapter 7, Fallacies of Confusion. C. L. Hamblin, Fallacies. Methuen London, 1970. Fearnside, W. Ward and William B. Holther, Fallacy: The Counterfeit of Argument, 1959. Vincent F. Hendricks, Thought 2 Talk: A Crash Course in Reflection and Expression, New York: Automatic Press / VIP, 2005, ISBN 87 -991013 -7 -8 D. H. Fischer, Historians' Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought, Harper Torchbooks, 1970. Douglas N. Walton, Informal logic: A handbook for critical argumentation. Cambridge University Press, 1989. F. H. van Eemeren and R. Grootendorst, Argumentation, Communication and Fallacies: A Pragma-Dialectical Perspective, Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, 1992. Warburton Nigel, Thinking from A to Z, Routledge 1998. Sagan, Carl, The Demon-Haunted World: Science As a Candle in the Dark. Ballantine Books, March 1997 ISBN 0 -345 -40946 -9, 480 pp. 1996 hardback edition: Random House, ISBN 0 -394 -53512 -X Wikipedia- https: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Formal_fallacy