Interfaces in Solids q Coherent Semicoherent and Incoherent

- Slides: 13

Interfaces in Solids q Coherent, Semi-coherent and Incoherent interfaces. Part of MATERIALS SCIENCE & A Learner’s Guide ENGINEERING AN INTRODUCTORY E-BOOK Anandh Subramaniam & Kantesh Balani Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur- 208016 Email: anandh@iitk. ac. in, URL: home. iitk. ac. in/~anandh http: //home. iitk. ac. in/~anandh/E-book. htm

Interfaces in Solids q The character of interfaces play an profound role in the properties of materials. q Three kinds of interfaces are to be kept in view by a ‘materials scientist’: (i) solid-vapour, (ii) solid-liquid, (iii) solid-solid. Solid-solid interfaces are the most important of these three. q Classification of the kinds of solid-solid interfaces can be found in: Chapter_5 c_Crystal_Imperfections_2 D. ppt. q The important class of interfaces, which we will discuss in this chapter, are interfaces between crystals. q An interface is a region of higher energy than the bounding crystals. This and other aspects of interfaces lead to important phenomena (only some types of interfaces may show a specific feature): Segregation of ‘impurity’ atoms to the interface Enhanced diffusivity along the interface Heterogeneous nucleation of second phase at the interface Weakening of the interface at ‘high’ temperatures (with possibility of slip along the interface– play an important role in creep) Selective electro-chemical attack of the interface. q Interface can be sharp (e. g. twin boundary) or diffuse (e. g. between grain and glass in Si 3 N 4 systems).

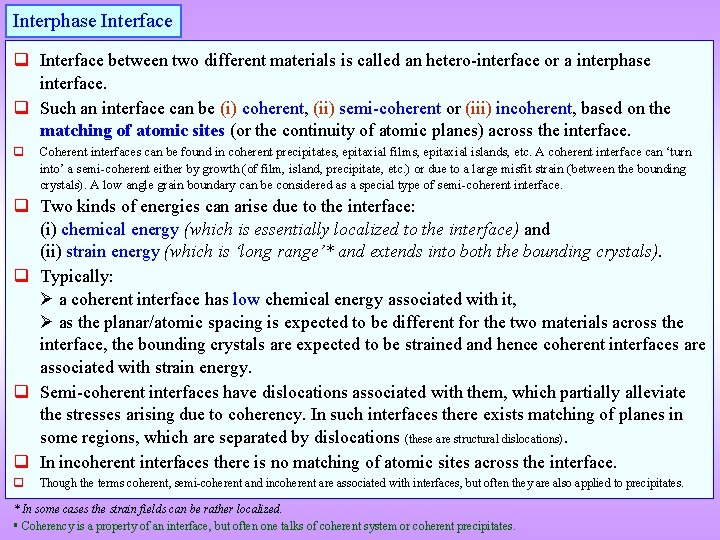

Interphase Interface q Interface between two different materials is called an hetero-interface or a interphase interface. q Such an interface can be (i) coherent, (ii) semi-coherent or (iii) incoherent, based on the matching of atomic sites (or the continuity of atomic planes) across the interface. q Coherent interfaces can be found in coherent precipitates, epitaxial films, epitaxial islands, etc. A coherent interface can ‘turn into’ a semi-coherent either by growth (of film, island, precipitate, etc. ) or due to a large misfit strain (between the bounding crystals). A low angle grain boundary can be considered as a special type of semi-coherent interface. q Two kinds of energies can arise due to the interface: (i) chemical energy (which is essentially localized to the interface) and (ii) strain energy (which is ‘long range’* and extends into both the bounding crystals). q Typically: a coherent interface has low chemical energy associated with it, as the planar/atomic spacing is expected to be different for the two materials across the interface, the bounding crystals are expected to be strained and hence coherent interfaces are associated with strain energy. q Semi-coherent interfaces have dislocations associated with them, which partially alleviate the stresses arising due to coherency. In such interfaces there exists matching of planes in some regions, which are separated by dislocations (these are structural dislocations). q In incoherent interfaces there is no matching of atomic sites across the interface. q Though the terms coherent, semi-coherent and incoherent are associated with interfaces, but often they are also applied to precipitates. * In some cases the strain fields can be rather localized. Coherency is a property of an interface, but often one talks of coherent system or coherent precipitates.

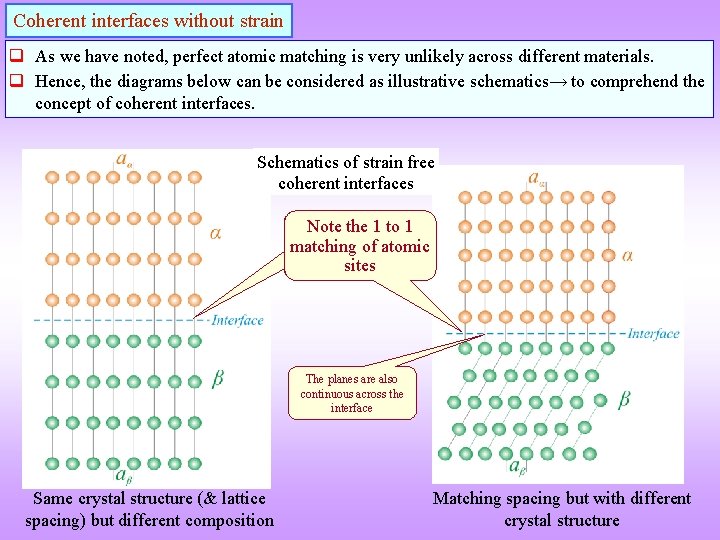

Coherent interfaces without strain q As we have noted, perfect atomic matching is very unlikely across different materials. q Hence, the diagrams below can be considered as illustrative schematics→ to comprehend the concept of coherent interfaces. Schematics of strain free coherent interfaces Note the 1 to 1 matching of atomic sites The planes are also continuous across the interface Same crystal structure (& lattice spacing) but different composition Matching spacing but with different crystal structure

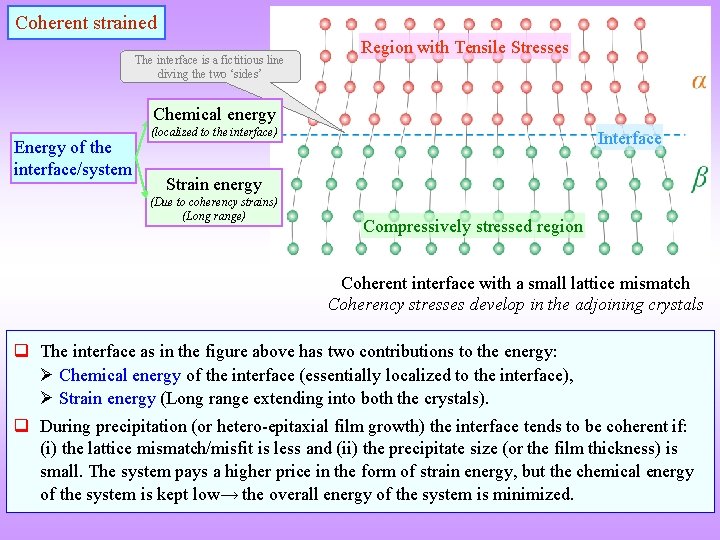

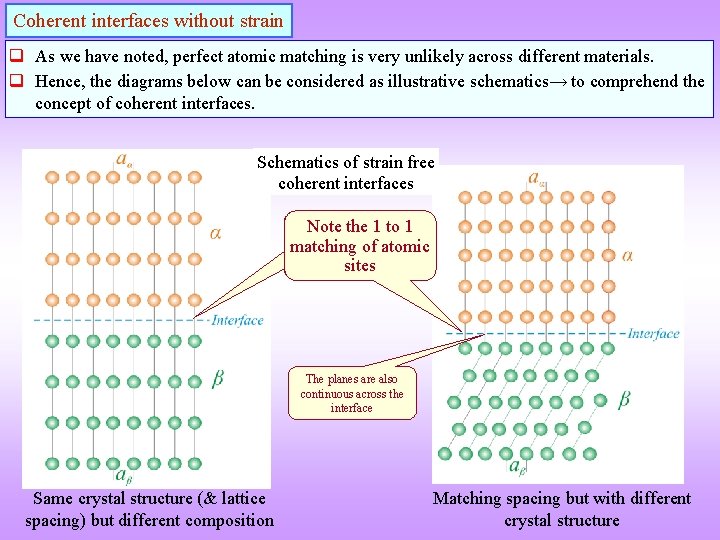

Coherent strained The interface is a fictitious line diving the two ‘sides’ Region with Tensile Stresses Chemical energy Energy of the interface/system (localized to the interface) Interface Strain energy (Due to coherency strains) (Long range) Compressively stressed region Coherent interface with a small lattice mismatch Coherency stresses develop in the adjoining crystals q The interface as in the figure above has two contributions to the energy: Chemical energy of the interface (essentially localized to the interface), Strain energy (Long range extending into both the crystals). q During precipitation (or hetero-epitaxial film growth) the interface tends to be coherent if: (i) the lattice mismatch/misfit is less and (ii) the precipitate size (or the film thickness) is small. The system pays a higher price in the form of strain energy, but the chemical energy of the system is kept low→ the overall energy of the system is minimized.

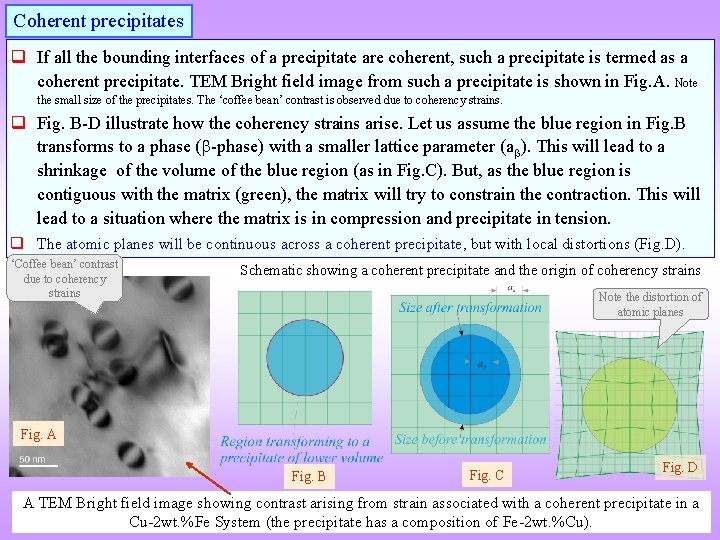

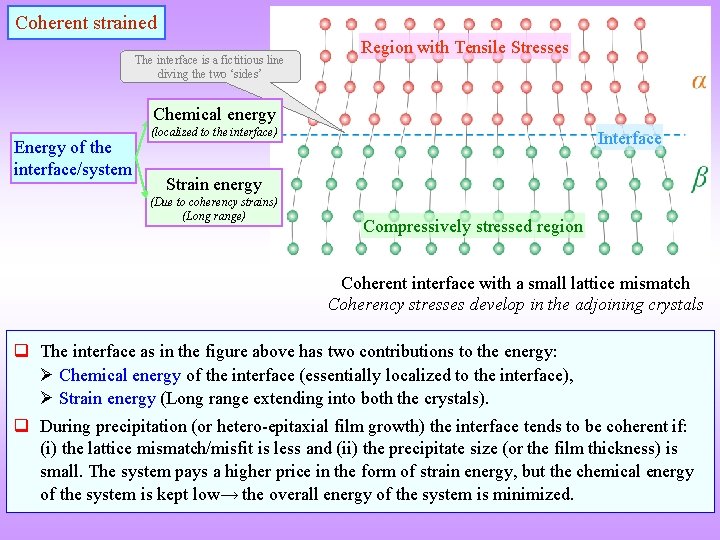

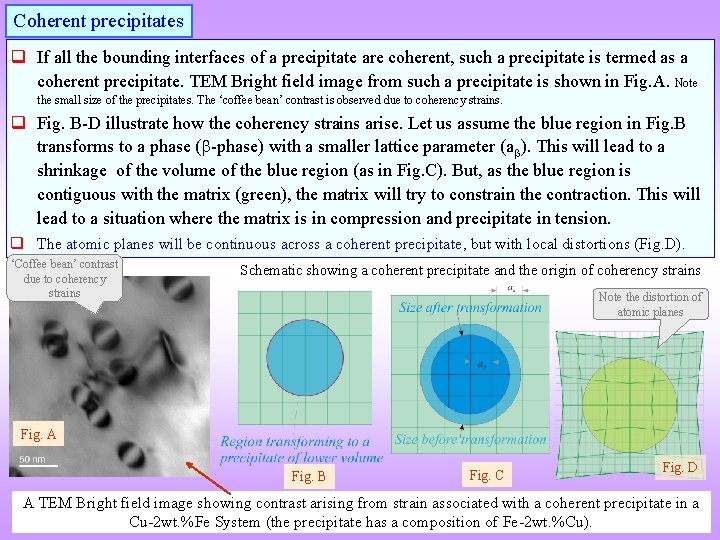

Coherent precipitates q If all the bounding interfaces of a precipitate are coherent, such a precipitate is termed as a coherent precipitate. TEM Bright field image from such a precipitate is shown in Fig. A. Note the small size of the precipitates. The ‘coffee bean’ contrast is observed due to coherency strains. q Fig. B-D illustrate how the coherency strains arise. Let us assume the blue region in Fig. B transforms to a phase ( -phase) with a smaller lattice parameter (a ). This will lead to a shrinkage of the volume of the blue region (as in Fig. C). But, as the blue region is contiguous with the matrix (green), the matrix will try to constrain the contraction. This will lead to a situation where the matrix is in compression and precipitate in tension. q The atomic planes will be continuous across a coherent precipitate, but with local distortions (Fig. D). ‘Coffee bean’ contrast due to coherency strains Schematic showing a coherent precipitate and the origin of coherency strains Note the distortion of atomic planes Fig. A Fig. B Fig. C Fig. D A TEM Bright field image showing contrast arising from strain associated with a coherent precipitate in a Cu-2 wt. %Fe System (the precipitate has a composition of Fe-2 wt. %Cu).

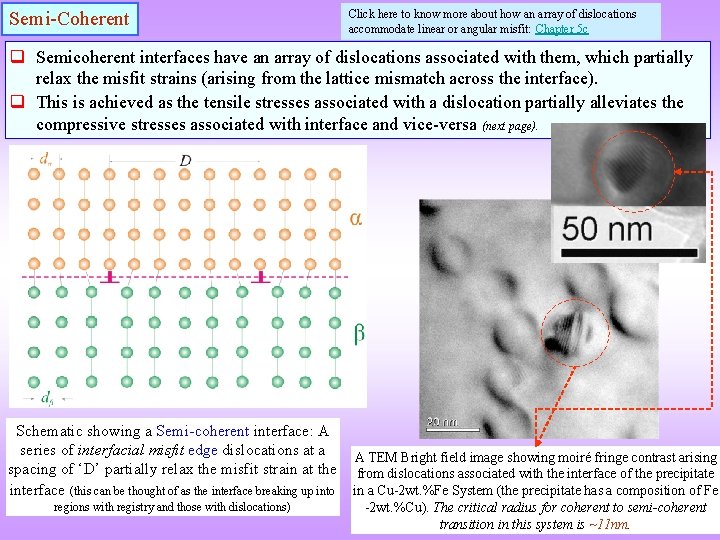

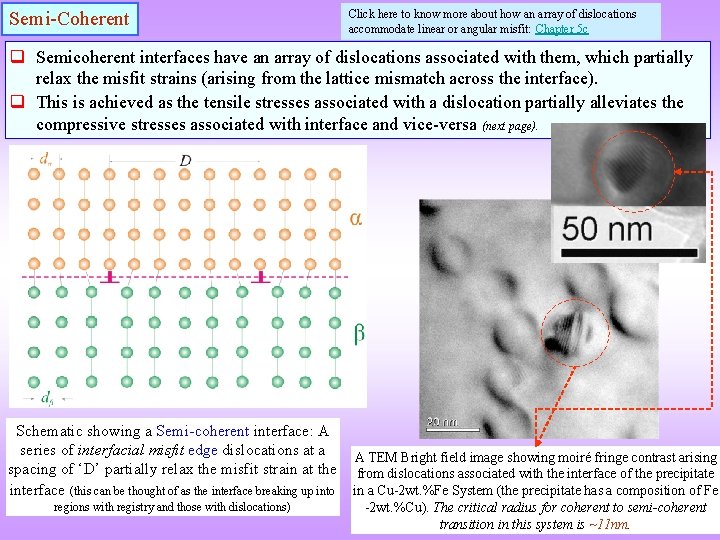

Semi-Coherent Click here to know more about how an array of dislocations accommodate linear or angular misfit: Chapter 5 c q Semicoherent interfaces have an array of dislocations associated with them, which partially relax the misfit strains (arising from the lattice mismatch across the interface). q This is achieved as the tensile stresses associated with a dislocation partially alleviates the compressive stresses associated with interface and vice-versa (next page). Schematic showing a Semi-coherent interface: A series of interfacial misfit edge dislocations at a spacing of ‘D’ partially relax the misfit strain at the interface (this can be thought of as the interface breaking up into regions with registry and those with dislocations) A TEM Bright field image showing moiré fringe contrast arising from dislocations associated with the interface of the precipitate in a Cu-2 wt. %Fe System (the precipitate has a composition of Fe -2 wt. %Cu). The critical radius for coherent to semi-coherent transition in this system is ~11 nm.

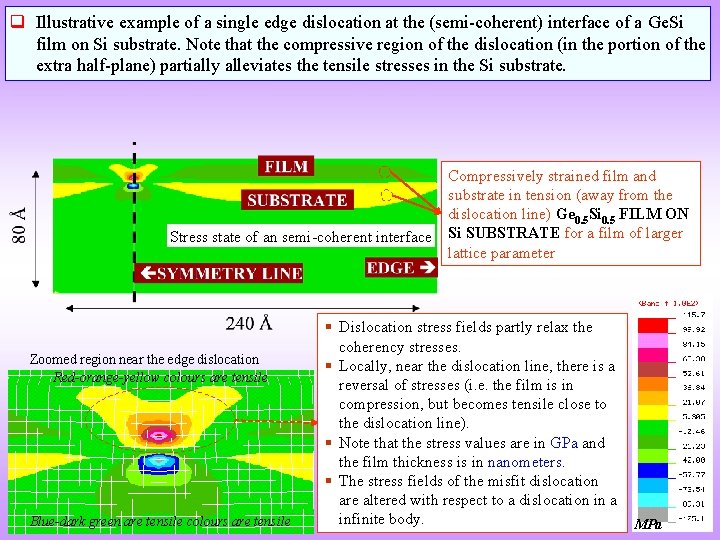

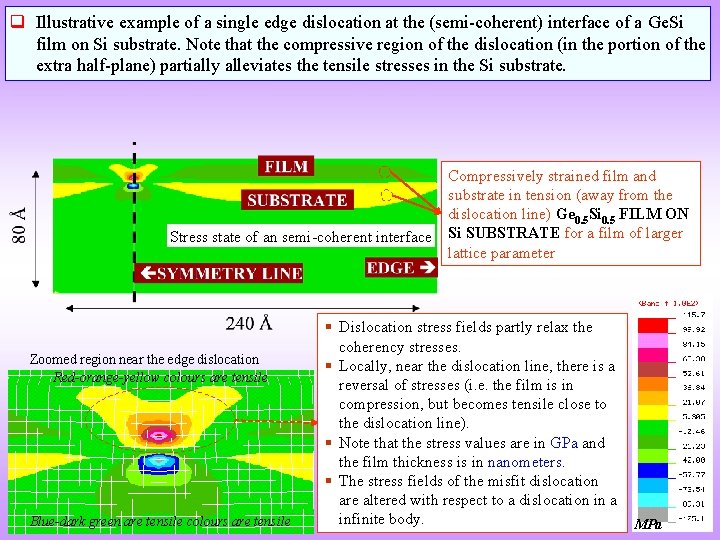

q Illustrative example of a single edge dislocation at the (semi-coherent) interface of a Ge. Si film on Si substrate. Note that the compressive region of the dislocation (in the portion of the extra half-plane) partially alleviates the tensile stresses in the Si substrate. Stress state of an semi-coherent interface Zoomed region near the edge dislocation Red-orange-yellow colours are tensile Blue-dark green are tensile colours are tensile Compressively strained film and substrate in tension (away from the dislocation line) Ge 0. 5 Si 0. 5 FILM ON Si SUBSTRATE for a film of larger lattice parameter Dislocation stress fields partly relax the coherency stresses. Locally, near the dislocation line, there is a reversal of stresses (i. e. the film is in compression, but becomes tensile close to the dislocation line). Note that the stress values are in GPa and the film thickness is in nanometers. The stress fields of the misfit dislocation are altered with respect to a dislocation in a infinite body. MPa

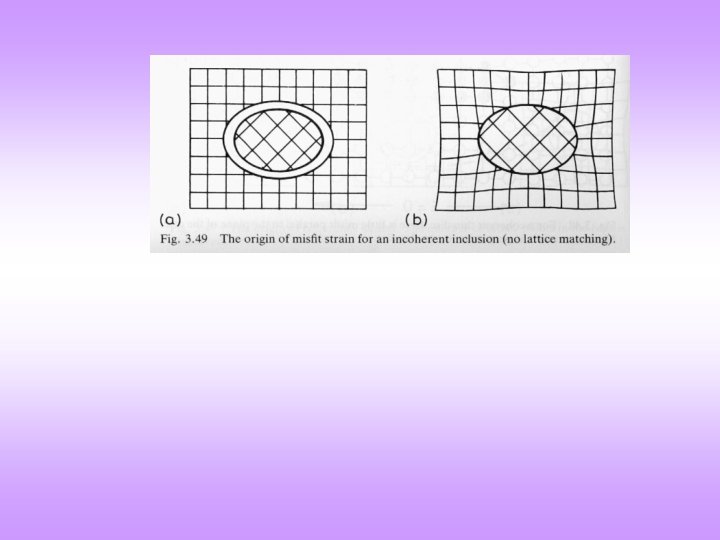

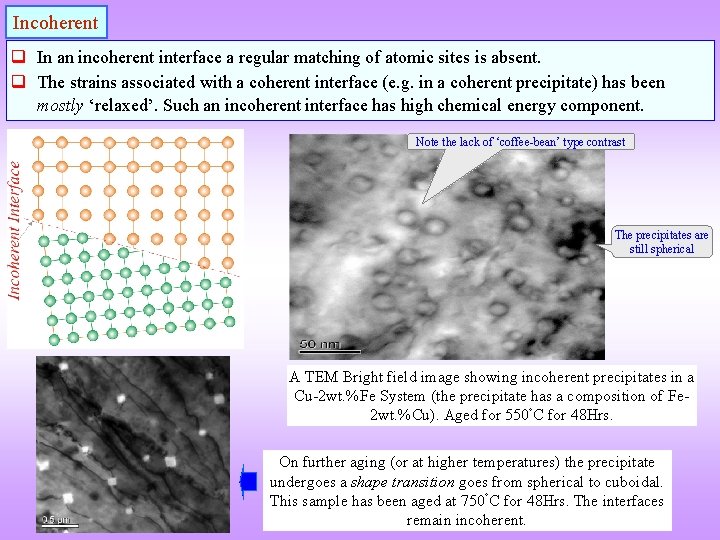

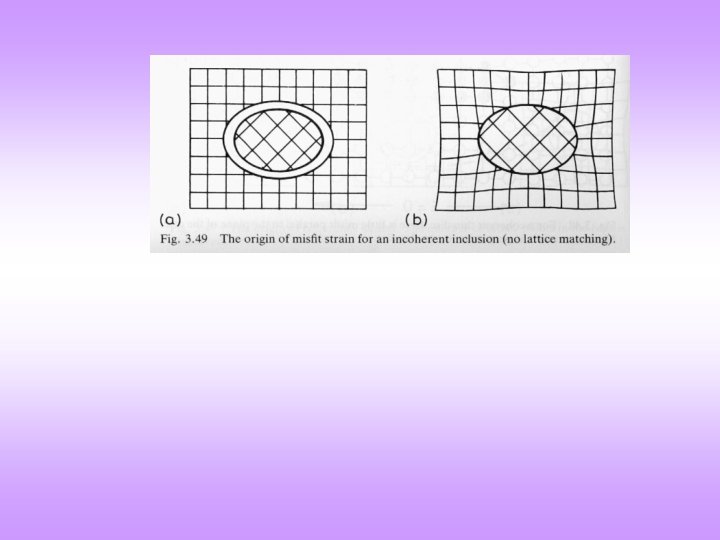

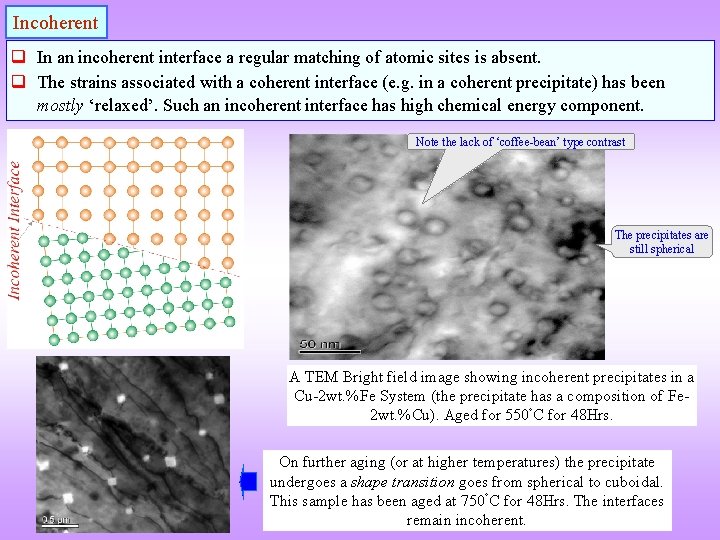

Incoherent q In an incoherent interface a regular matching of atomic sites is absent. q The strains associated with a coherent interface (e. g. in a coherent precipitate) has been mostly ‘relaxed’. Such an incoherent interface has high chemical energy component. Note the lack of ‘coffee-bean’ type contrast The precipitates are still spherical A TEM Bright field image showing incoherent precipitates in a Cu-2 wt. %Fe System (the precipitate has a composition of Fe 2 wt. %Cu). Aged for 550 C for 48 Hrs. On further aging (or at higher temperatures) the precipitate undergoes a shape transition goes from spherical to cuboidal. This sample has been aged at 750 C for 48 Hrs. The interfaces remain incoherent.

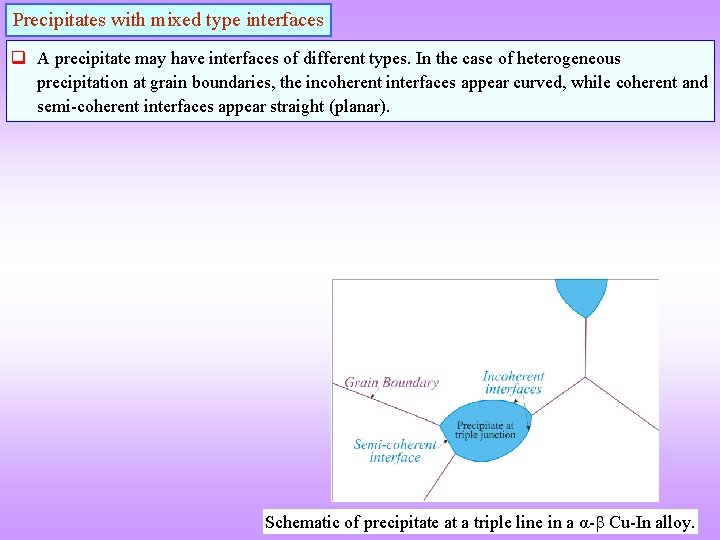

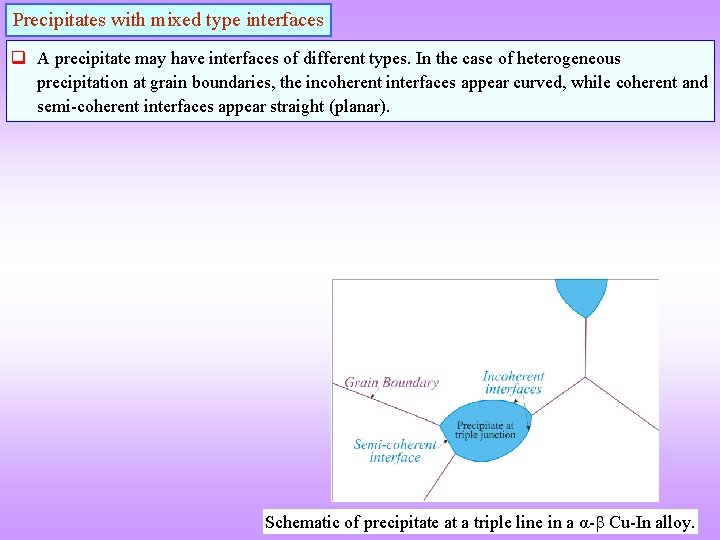

Precipitates with mixed type interfaces q A precipitate may have interfaces of different types. In the case of heterogeneous precipitation at grain boundaries, the incoherent interfaces appear curved, while coherent and semi-coherent interfaces appear straight (planar). Schematic of precipitate at a triple line in a α- Cu-In alloy.

Funda Check What is a ‘habit plane’? q If the transformation product is in the shape of a plate, then the plane of the plate is called a Habit plane. Though there are other definitions possible, this is the simplest one. q Sometimes the habit plane may not have low Miller indices, in which case it may be considered ‘irrational’.

End