INTERACTIONS AMONG MICROBIAL POPULATIONS Successful bioremediation relies not

INTERACTIONS AMONG MICROBIAL POPULATIONS

Successful bioremediation relies not only on metabolic capacities of microbial populations in a given environment, but also on their reciprocal relationships

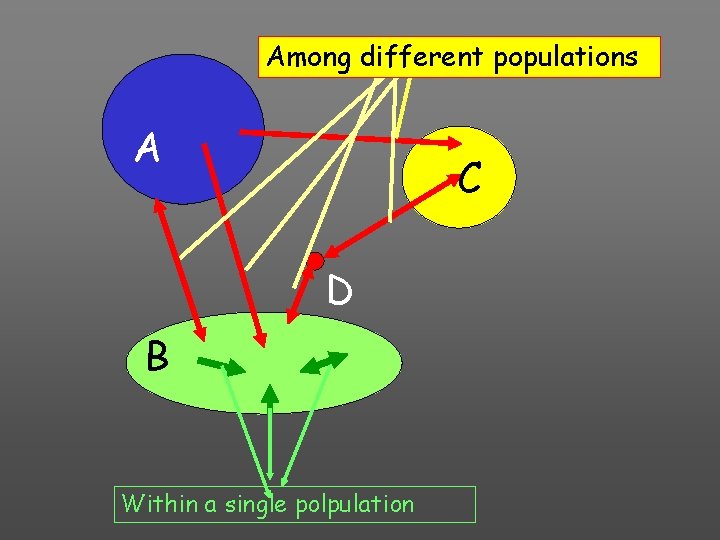

Among different populations A C D B Within a single polpulation

INTERACTIONS WITHIN A SINGLE MICROBIAL POPULATION POSITIVE NEGATIVE NEUTRALISM (no interactions) is a rare, and perhaps only theoretical phenomenon

POSITIVE interactions within a single population are called COOPERATION Evidences: o. Extended lag period o. Complete failure of growth o“minimum infectious dose” of pathogenic microbial populations

Cooperation occurs within the population because the semipermeable cell membranes of microorganisms are imperfect and tend to “leak” low-molecular-weight metabolic intermediates that are essential for biosynthesis and growth.

In a population, a significant extracellular concentration of these metabolites is established that counteracts further loss and facilitate reabsorbtion. For a single cell or a very low density population, however, losses may exceed replacements rates and prevent growth

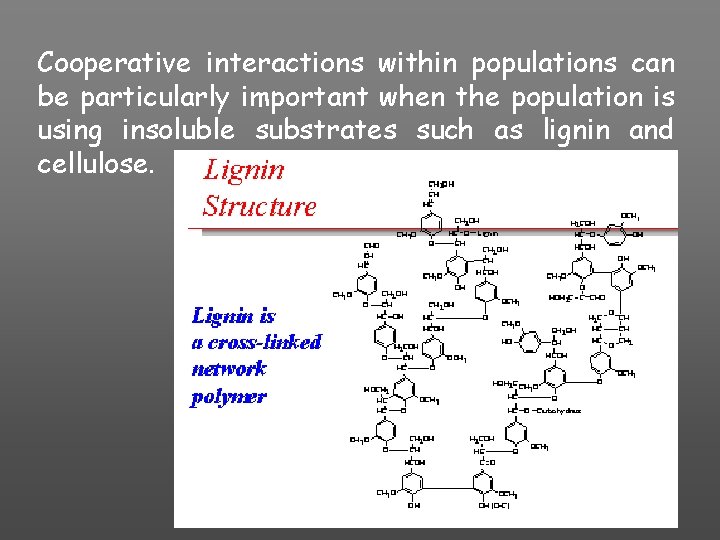

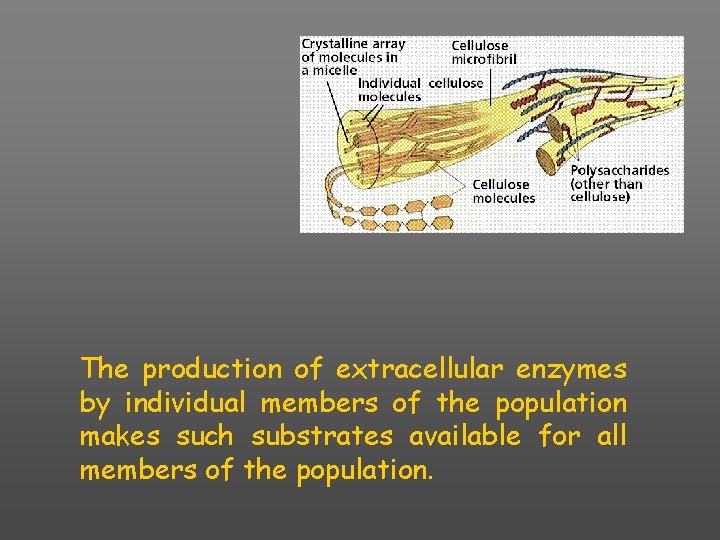

Cooperative interactions within populations can be particularly important when the population is using insoluble substrates such as lignin and cellulose.

The production of extracellular enzymes by individual members of the population makes such substrates available for all members of the population.

Cooperation in a population can also function as a protective mechanism against hostile environmental factors. It is commonly observed in the laboratory that a given concentration of a metabolic inhibitor has less effect on a dense cell suspension than on a dilute one

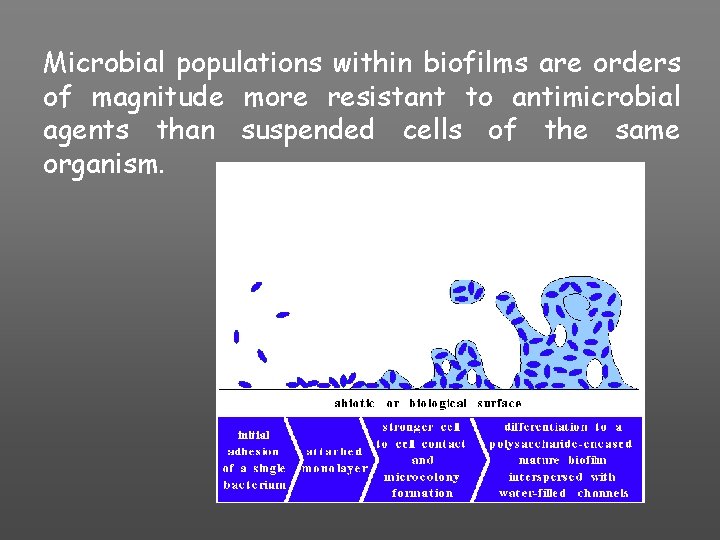

Microbial populations within biofilms are orders of magnitude more resistant to antimicrobial agents than suspended cells of the same organism.

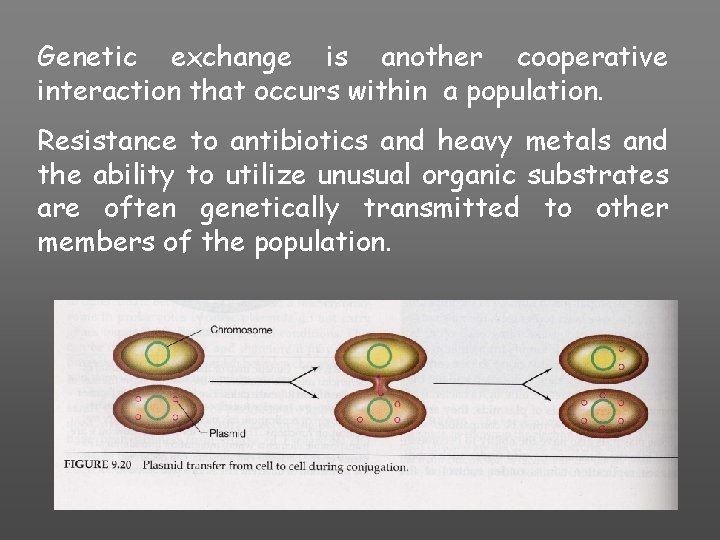

Genetic exchange is another cooperative interaction that occurs within a population. Resistance to antibiotics and heavy metals and the ability to utilize unusual organic substrates are often genetically transmitted to other members of the population.

NEGATIVE interaction within a single microbial population are called: competition Because members of a microbial population all use the same substrates and occupy the same ecological niche there is a SUBSTRATE SUBTRACTION In a natural environment where concentration of available substrates are very low the competition increases.

Within populations of predatory microorganisms competition occurs for available prey Within populations of parasitic microorganisms competition occurs for available host cells Infection of a host cell by a member of a population effectively precludes further infections of that cell by other members of the population.

Negative interactions is also due to production metabolites that became toxic at high levels (H 2 S, lactic acid, ethanol). Fatty acid accumulation biodegradation can block during hydrocarbon further microbial metabolism of the hydrocarbon substrates

and the accumulation of dichloroaniline from 3, 4 dichloropropionanilide(propanil) catabolism can stop further growth of Penicillium pisciarum.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN DIVERSE MICROBIAL POPULATIONS

Possible interactions between microbial populations can be recognized as no interactions (neutralism) negative interactions (competition and amensalism); positive interactions (commensalism, synergism and mutualism); interactions that are positive for one and negative for the other population (parasitism and predation)

NEUTRALISM Lack of interactions between two microbial populations Cannot occur between populations having the same or overlapping functional roles within a community Is more likely between populations with extremely different metabolic capabilities

Neutralism occurs between microbial populations that are spatially distant from each other. In oligotrophic densities environment at low population Environmental conditions that do not permit active microbial growth favor neutralism - microorganisms frozen in an ice matrix -in the atmosphere where only alloctonous microorganisms exist - resting stages of microbial life

Positive interactions enhance the abilities of some populations to survive as part of the community within a particular habitat. The development of positive interactions allows microorganisms to use available resources more efficiently and to occupy habitats that otherwise could not be inhabited.

Mutualistic between essentially relationships microbial new (SYMBIOSES) populations organisms create capable of occupying niches that could not be occupied by either organism alone. Positive interactions between microbial populations are based on combined physical and metabolic capabilities that enhance growth and/or survival rates.

COMMENSALISM Commensalism is a unidirectional relationship between two populations One population benefits while the other remains unaffected Although commensal relationships are common between microbial populations, they are not obligatory

The recipient population needs the benefit, but it can receive the necessary assistance from other populations with comparable metabolic capabilities. Facultative anaerobes use oxygen and lower the oxygen tension therefore creating a habitat suitable for the growth of obligate anaerobes. Some microbial populations produce and excrete growth factors such as vitamins or amino acids that can be used by other microbial populations Flavobacterium brevis excretes cysteine which Legionella pneumophila can use in aquatic habitats.

Important interactions in the environment occur between methane producing bacteria that benefit from hydrogen and acetate or carbon dioxide produced fermenting in anoxic sediments. by bacteria

Acid production from a microbial population may release compounds that are bound or inaccessible to a second population. Such desorbption processes are probably common in soil where many compound can be bonded to mineral particles or humic materials.

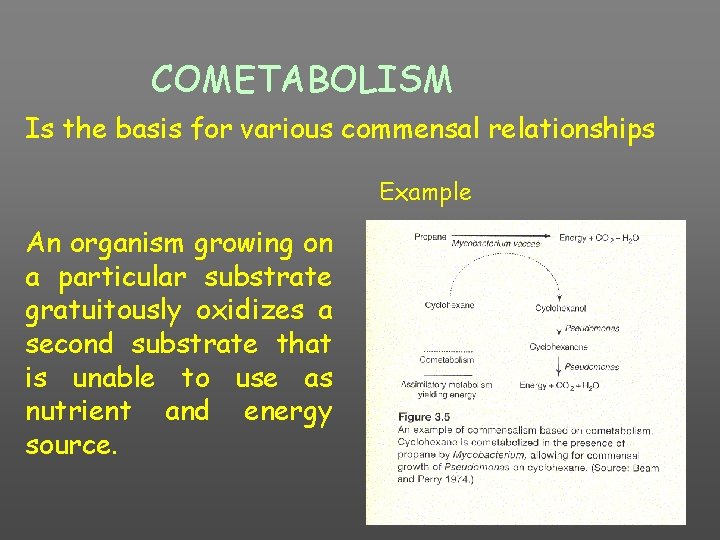

COMETABOLISM Is the basis for various commensal relationships Example An organism growing on a particular substrate gratuitously oxidizes a second substrate that is unable to use as nutrient and energy source.

Removal or neutralization of a toxic material The ability to destroy toxic factors widespread in microbial communities The oxidation of hydrogen sulfide by Beggiatoa is an example of detoxification that benefits H 2 S-sensitive aerobic microbial populations. is

Precipitation of heavy metals, such as mercury by sulfate reducers provides an additional example of detoxification. Production of volatile mercuric compounds by bacterial populations in aquatic habitats removes the toxic metal from the habitat.

SYNERGISM (PROTOCOOPERATION)

Both populations benefit from the relationship Both populations are capable of surviving in their natural environment on their own although when initially formed, the association offers some mutual advantages. Synergistic relationships are also loose in the sense that one member of the populationis often easily replaced by another.

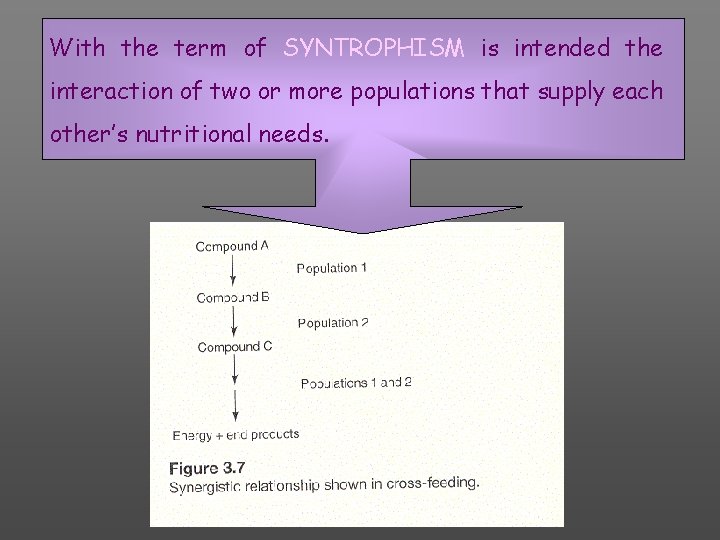

With the term of SYNTROPHISM is intended the interaction of two or more populations that supply each other’s nutritional needs.

Syntrophism may allow microbial populations to perform activities, such as the synthesis of a product that neither population could perform alone.

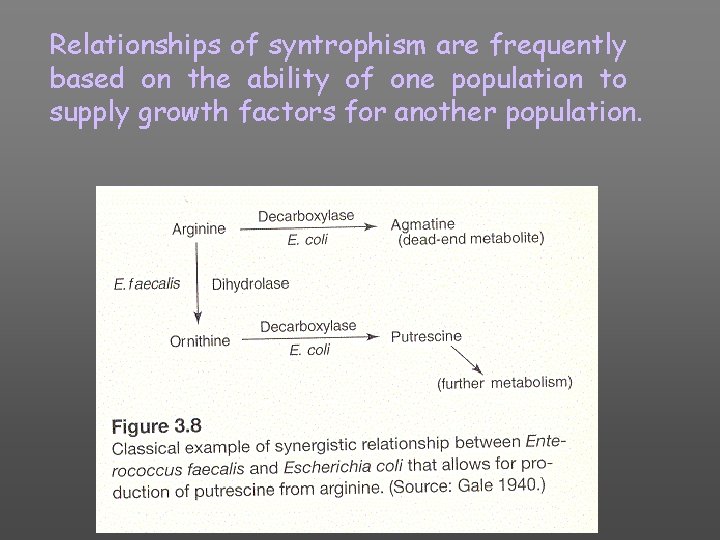

Relationships of syntrophism are frequently based on the ability of one population to supply growth factors for another population.

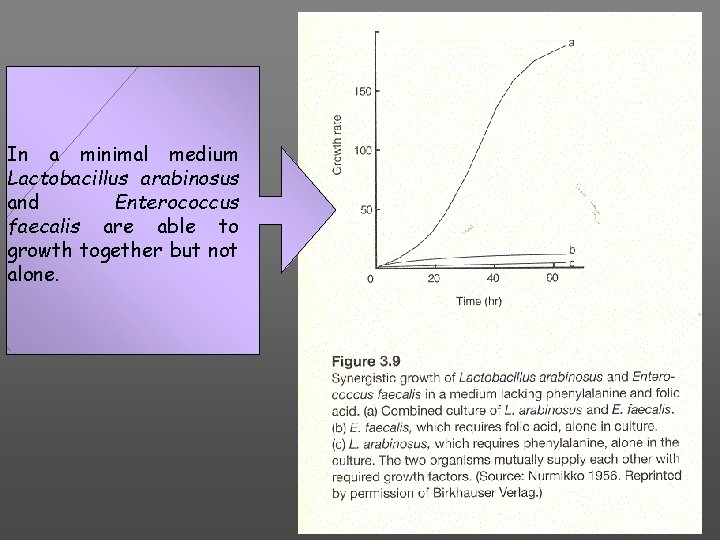

In a minimal medium Lactobacillus arabinosus and Enterococcus faecalis are able to growth together but not alone.

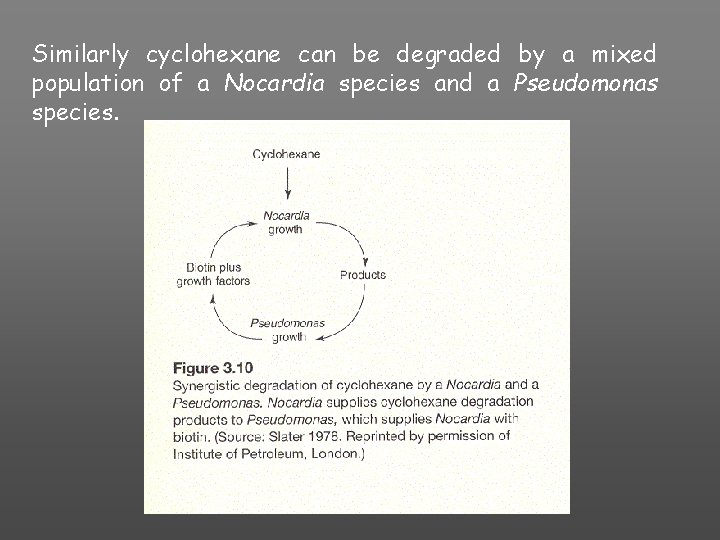

Similarly cyclohexane can be degraded by a mixed population of a Nocardia species and a Pseudomonas species.

Several important degradation pathways of agricultural pesticides involve synergistic relationships. Arthrobacter and Streptomyces strains isolated from soil are capable of completely degrading the organophosphate insecticide diazinon and can grow on this compound as the only source of carbon and energy. This is accomplished by synergistic attack; alone neither culture can mineralize the pyrimidinyl ring of diazinon or grow on this compound.

In a chemostat enrichment culture, Pseudomonas stutzeri is capable of cleaving the organophosphate insecticide parathion to p-nitrophenol and diethylthiophosphate, but it is not capable of utilizing either of the resulting moieties. Peudomonas aeruginosa can mineralize the p-nitrophenol but is incapable of attacking intact parathion. Synergistically, the two-component enrichment degrades parathion with high efficiency, P. stutzeri apparently utilizing products excreted by P. aeruginosa.

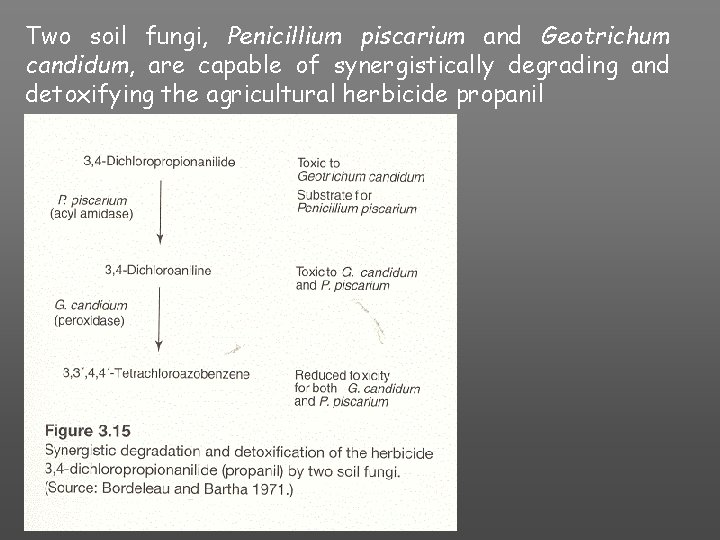

Two soil fungi, Penicillium piscarium and Geotrichum candidum, are capable of synergistically degrading and detoxifying the agricultural herbicide propanil

Archaeal production populations involved (methanogens) have in methane interesting synergistic relationships with bacterial and other microbial populations

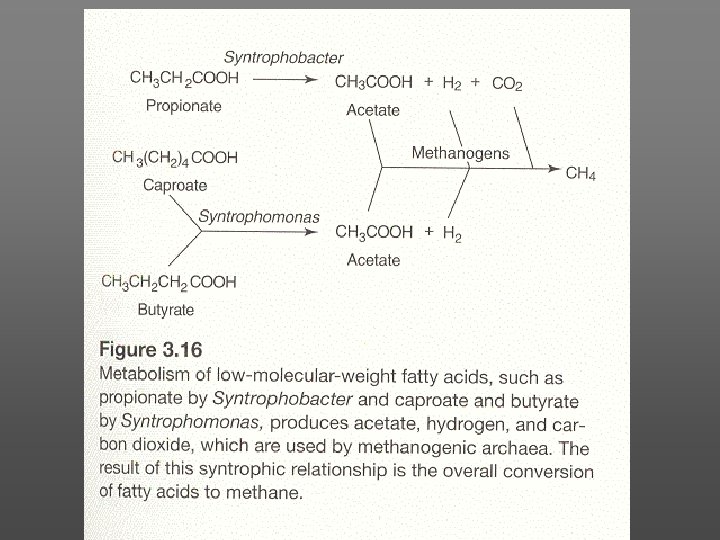

The metabolism of the methanogens maintains very low concentrations of H 2 The removal of the H 2 end product draws fermentation the equilibrium of fatty additional H 2 production, toward acid increasing the growth rates of Syntrophomonas and Syntrophobacter species. It takes special hydrogen removal measures to cultivate these fermenters in the absence of methanogens.

Although they mediate the ultimate anaerobic decomposition of cellulosic plant residues in lake sediments, swamps, bogs, and in the digestive tracts of various animals, the substrate range of methanogenic archaea is extremely limited.

The principal metabolic reaction is the reduction of CO 2 with H 2 to CH 4. The CO 2 and H 2 are produced in fermentation reactions. The CH 4 and residual CO 2 are evolved as "biogas" or "marsh gas. "

Only CO, formate, methylamines, methanol, and acetate are used as additional carbon sources by some methanogens. Because of this narrow substrate range, methanogens rely on anaerobic cellulose degraders to form glucose and other fermentable carbohydrates and on mixed acid fermenters to form a range of short-chain fatty acids.

These are fermented further to H 2, CO 4, and other products by bacteria very closely syntrophic with methanogens. Methanobacterium bryantii (formerly M. omelianskii) was kept in culture collection for 26 years after its original description in 1941 before it was recognized as the syntrophic association of the methanogen organism. proper and a fermentative "S"

This and similar syntrophic fermenters produce H 2, oxidized fatty acid, and/or CO 2, but are able to do this only if the evolved hydrogen is removed efficiently and does not accumulate to inhibitory concentrations. By reducing CO 2 to CH 4, the methanogen fulfills this function. The "S" organism and similar syntrophic fermenters were later classified as the Syntrophomonas and Syntrophobacter genera. Both of these bacteria are hydrogen producers and require the presence of the methanogen as hydrogen removers.

Syntrophic reactions are facilitated by bacterial aggregate (floc) formations that bring the participants into intimate contact with each other. In the anaerobic digestion of a whey effluent, lactate and ethanol are converted to methane by a threemembered syntrophic association.

CH 4

Mutualism Mutualistic relationships between populations can be considered extended synergism. Mutualism is an obligatory relationship between two populations that benefits both populations.

A mutualistic relationship is highly specific—one member of the association ordinarily cannot be replaced by another related species. Historically mutualism also has been called symbiosis, and the term is still used to describe some instances of a mutualistic relationship. For example, the relationship between nitrogenfixing bacteria and certain plants has been called nitrogen-fixing symbiosis rather than nitrogenfixing mutualism. The latter would be a more precise contemporary term as ecologists now use symbiosis to indicate any sustained interpopulation interaction.

Mutualism requires close physical proximity between the interacting populations. Relationships of mutualism allow organisms to exist in habitats that could not be occupied by either population alone. This does not exclude the possibility that the populations may exist separately in other habitats.

The metabolic activities and physiological tolerances of populations involved in mutualistic relationships are normally quite different from those of either population by itself. Mutualistic relationships between microorganisms allow the microorganims to act as if they are a single organism with a unique identity.

NEGATIVE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MICROBIAL POPULATIONS COMPETITION AMENSALISM (ANTAGONISM) Microorganisms that produce toxic substances will naturally have a competitive advantage The terms Antibiosis and Allelopathy have been used to describe such cases of chemical inhibition. PARASITISM

As a general rule, organic compounds are more effectively degraded in environments containing many microorganisms than a pure colture of a single organism This is due to several factors: The range of degradative capabilities represented in a complex community of many bacteria and fungi is far greater than the capabilities of any single organism alone

The product of partial biodegradation of a xenobiotic by one organism may serve as a substrate for another organism The concerted action of several different organisms may lead to complete mineralization of the xenobiotic A microbial community is also likely to be more resistant than a solitary species to toxic products because one of its members may be able to detoxify it

A microbial community is dynamic: its composition responds to environmental conditions, coming over time to exploit available nutrients in a most effective manner Thus, when a new biotrasformable organic compound is presented at a constant level to such a community, a period of adaptation ensues, after which the rate of biotrasformation of the organic compound is generally seen to be much increase

- Slides: 57