Integers Number Theory Properties of Integers For this

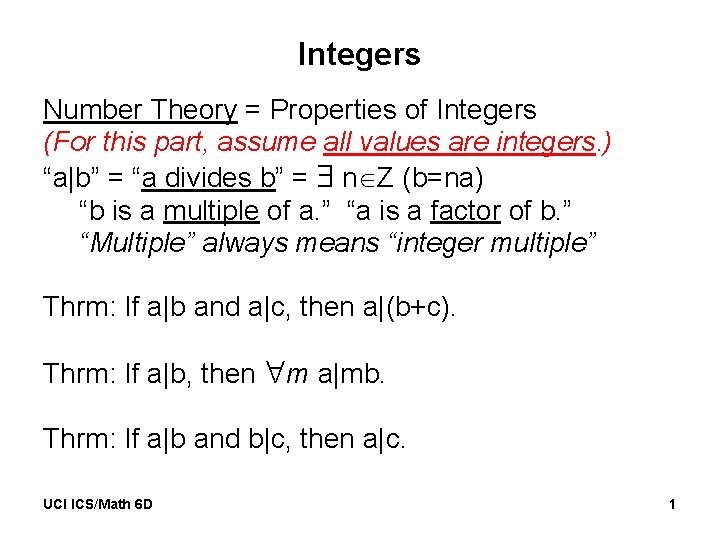

Integers Number Theory = Properties of Integers (For this part, assume all values are integers. ) “a|b” = “a divides b” = n Z (b=na) “b is a multiple of a. ” “a is a factor of b. ” “Multiple” always means “integer multiple” Thrm: If a|b and a|c, then a|(b+c). Thrm: If a|b, then m a|mb. Thrm: If a|b and b|c, then a|c. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 1

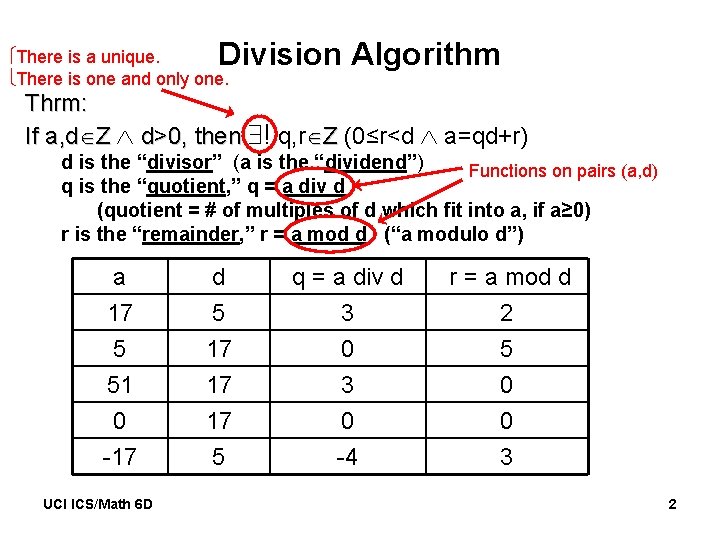

Division Algorithm There is a unique. There is one and only one. Thrm: If a, d Z d>0, then ! q, r Z (0≤r<d a=qd+r) d is the “divisor” (a is the “dividend”) Functions on pairs (a, d) q is the “quotient, ” q = a div d (quotient = # of multiples of d which fit into a, if a≥ 0) r is the “remainder, ” r = a mod d (“a modulo d”) a 17 5 51 d 5 17 17 q = a div d 3 0 3 r = a mod d 2 5 0 0 -17 17 5 0 -4 0 3 UCI ICS/Math 6 D 2

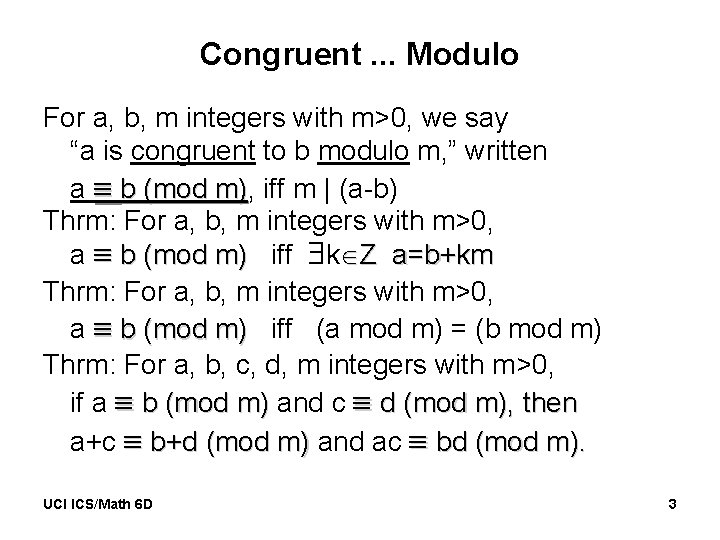

Congruent. . . Modulo For a, b, m integers with m>0, we say “a is congruent to b modulo m, ” written a b (mod m), m) iff m | (a-b) Thrm: For a, b, m integers with m>0, a b (mod m) iff k Z a=b+km Thrm: For a, b, m integers with m>0, a b (mod m) iff (a mod m) = (b mod m) Thrm: For a, b, c, d, m integers with m>0, if a b (mod m) and c d (mod m), then a+c b+d (mod m) and ac bd (mod m). UCI ICS/Math 6 D 3

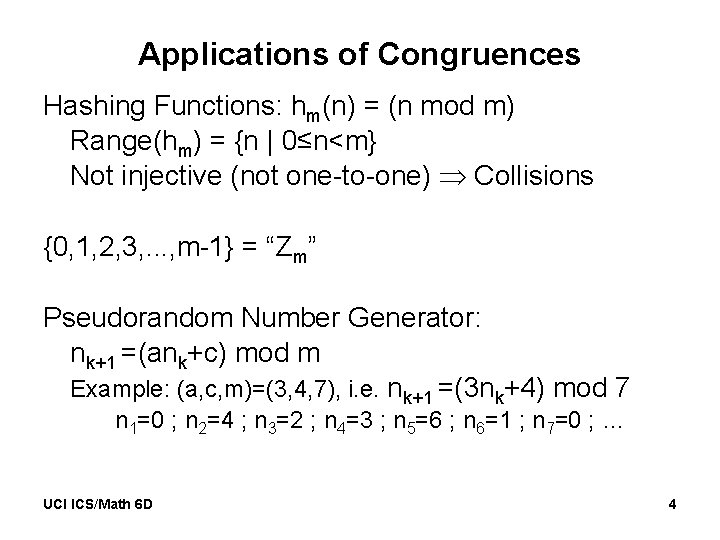

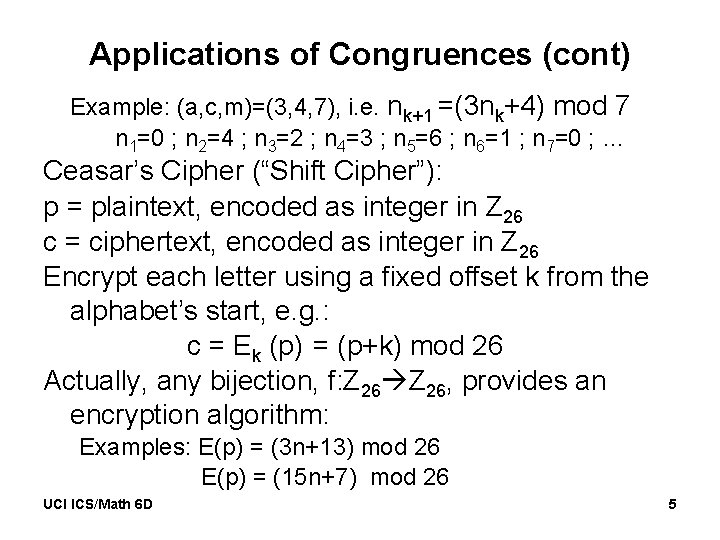

Applications of Congruences Hashing Functions: hm(n) = (n mod m) Range(hm) = {n | 0≤n<m} Not injective (not one-to-one) Collisions {0, 1, 2, 3, . . . , m-1} = “Zm” Pseudorandom Number Generator: nk+1 =(ank+c) mod m Example: (a, c, m)=(3, 4, 7), i. e. nk+1 =(3 nk+4) mod 7 n 1=0 ; n 2=4 ; n 3=2 ; n 4=3 ; n 5=6 ; n 6=1 ; n 7=0 ; … UCI ICS/Math 6 D 4

Applications of Congruences (cont) Example: (a, c, m)=(3, 4, 7), i. e. nk+1 =(3 nk+4) mod 7 n 1=0 ; n 2=4 ; n 3=2 ; n 4=3 ; n 5=6 ; n 6=1 ; n 7=0 ; … Ceasar’s Cipher (“Shift Cipher”): p = plaintext, encoded as integer in Z 26 c = ciphertext, encoded as integer in Z 26 Encrypt each letter using a fixed offset k from the alphabet’s start, e. g. : c = Ek (p) = (p+k) mod 26 Actually, any bijection, f: Z 26, provides an encryption algorithm: Examples: E(p) = (3 n+13) mod 26 E(p) = (15 n+7) mod 26 UCI ICS/Math 6 D 5

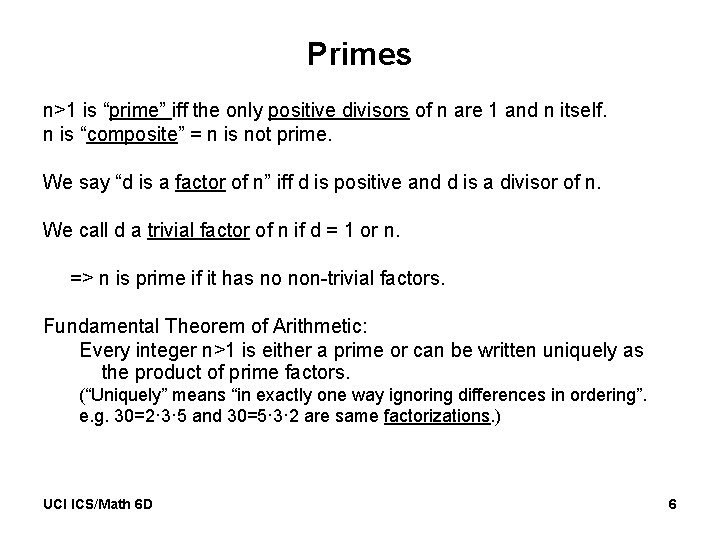

Primes n>1 is “prime” iff the only positive divisors of n are 1 and n itself. n is “composite” = n is not prime. We say “d is a factor of n” iff d is positive and d is a divisor of n. We call d a trivial factor of n if d = 1 or n. => n is prime if it has no non-trivial factors. Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic: Every integer n>1 is either a prime or can be written uniquely as the product of prime factors. (“Uniquely” means “in exactly one way ignoring differences in ordering”. e. g. 30=2· 3· 5 and 30=5· 3· 2 are same factorizations. ) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 6

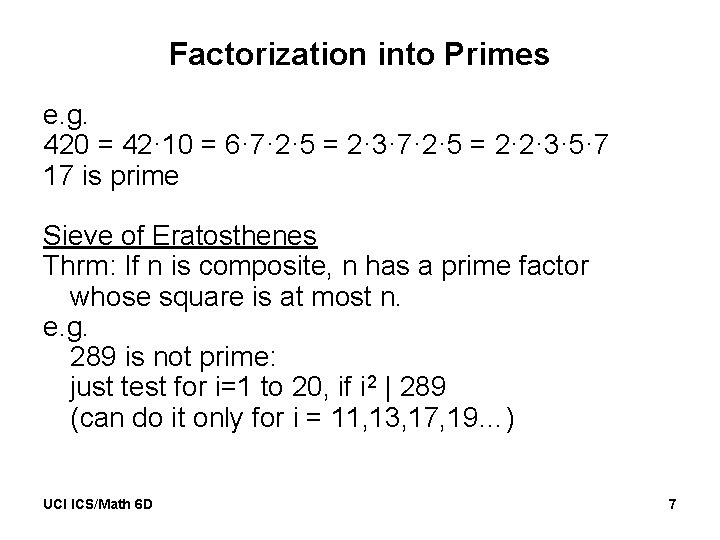

Factorization into Primes e. g. 420 = 42· 10 = 6· 7· 2· 5 = 2· 3· 7· 2· 5 = 2· 2· 3· 5· 7 17 is prime Sieve of Eratosthenes Thrm: If n is composite, n has a prime factor whose square is at most n. e. g. 289 is not prime: just test for i=1 to 20, if i 2 | 289 (can do it only for i = 11, 13, 17, 19…) UCI ICS/Math 6 D 7

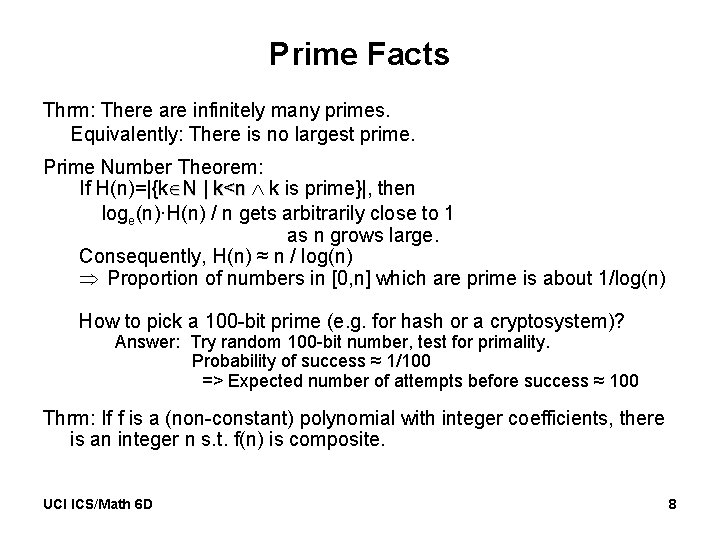

Prime Facts Thrm: There are infinitely many primes. Equivalently: There is no largest prime. Prime Number Theorem: If H(n)=|{k N | k<n k is prime}|, then loge(n)·H(n) / n gets arbitrarily close to 1 as n grows large. Consequently, H(n) ≈ n / log(n) Proportion of numbers in [0, n] which are prime is about 1/log(n) How to pick a 100 -bit prime (e. g. for hash or a cryptosystem)? Answer: Try random 100 -bit number, test for primality. Probability of success ≈ 1/100 => Expected number of attempts before success ≈ 100 Thrm: If f is a (non-constant) polynomial with integer coefficients, there is an integer n s. t. f(n) is composite. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 8

Prime Conjectures Goldbach’s Conjecture: Every even integer greater than 2 can be written as the sum of two primes. http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Goldbach's_conjecture The Twin Prime Conjecture: There are infinitely many primes p such that p+2 is also prime. http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Twin_prime_conjecture UCI ICS/Math 6 D 9

Greatest Common Divisor (gcd) When a and b are integers, not both 0, the “greatest common divisor” of a and b, denoted gcd(a, b), is the largest integer d such that d|a and d|b. Note: If a≠ 0, gcd(a, 0)=|a| Thrm: When a and b are integers, not both 0, if d|a and d|b, then d|gcd(a, b). Thrm: If a and b are integers, not both 0, gcd(a, b)=gcd(b, a) Thrm: If a and b are integers, not both 0, gcd( a , b ) = gcd( a , b mod a ) = gcd( a mod b , b ) Ref: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Greatest_common_divisor UCI ICS/Math 6 D 10

Least Common Multiple (lcm) If a, b>0, the “least common multiple” of a and b, denoted lcm(a, b), is the smallest m>0 such that a|m and b|m. Thrm: If a, b>0, then a · b = gcd(a, b) · lcm(a. b) Integers a and b are said to be “relatively prime” iff gcd(a, b)=1. Set S of integers is said to be “pairwise relatively prime” iff each pair of (different) elements in S is relatively prime. UCI ICS/Math 6 D 11

Finding gcd’s and lcm’s Method 1: Factor each number into primes j 1 j 2 jn k 1 k 2 kn a=p 1 ·p 2 ·. . . ·pn , b=p 1 ·p 2 ·. . . ·pn. Then min(j , k ) gcd(a, b)=p 1 1 1 ·p 2 2 2 ·. . . ·pn n n. max(j 1, k 1) max(j 2, k 2) max(jn, kn) lcm(a, b)=p 1 ·p 2 ·. . . ·pn. Method 2: Euclidean Algorithm: Find gcd(a, b) [using gcd(a, b)=gcd(a mod b, b)=gcd(b, a mod b)] Can then compute lcm(a, b)=a·b/gcd(a, b). Ref: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Euclidean_algorithm UCI ICS/Math 6 D 12

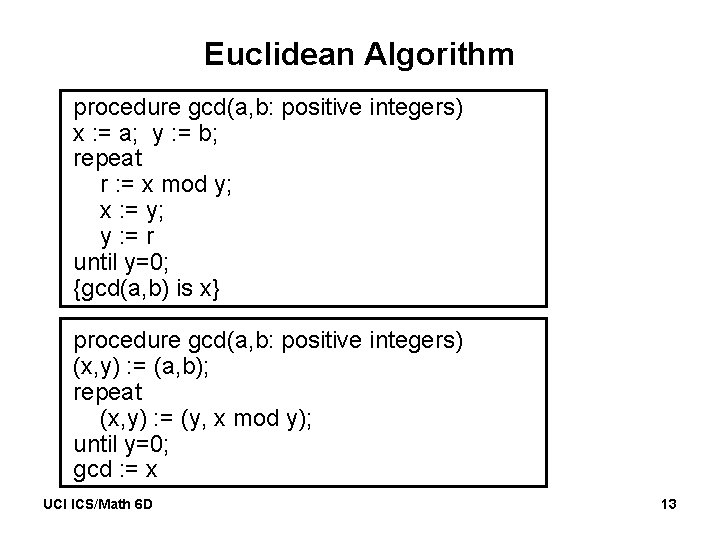

Euclidean Algorithm procedure gcd(a, b: positive integers) x : = a; y : = b; repeat r : = x mod y; x : = y; y : = r until y=0; {gcd(a, b) is x} procedure gcd(a, b: positive integers) (x, y) : = (a, b); repeat (x, y) : = (y, x mod y); until y=0; gcd : = x UCI ICS/Math 6 D 13

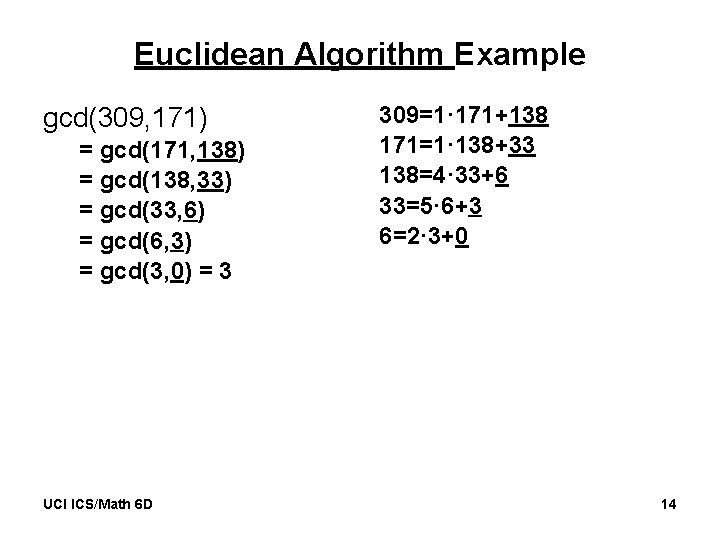

Euclidean Algorithm Example gcd(309, 171) = gcd(171, 138) = gcd(138, 33) = gcd(33, 6) = gcd(6, 3) = gcd(3, 0) = 3 UCI ICS/Math 6 D 309=1· 171+138 171=1· 138+33 138=4· 33+6 33=5· 6+3 6=2· 3+0 14

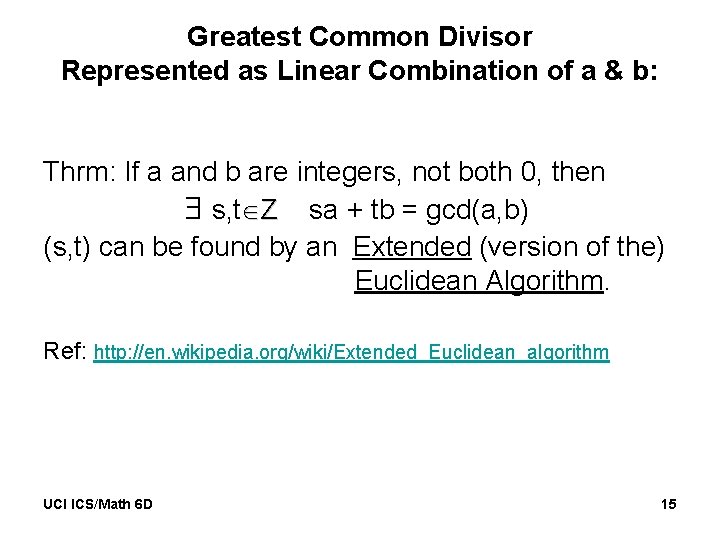

Greatest Common Divisor Represented as Linear Combination of a & b: Thrm: If a and b are integers, not both 0, then s, t Z sa + tb = gcd(a, b) (s, t) can be found by an Extended (version of the) Euclidean Algorithm. Ref: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Extended_Euclidean_algorithm UCI ICS/Math 6 D 15

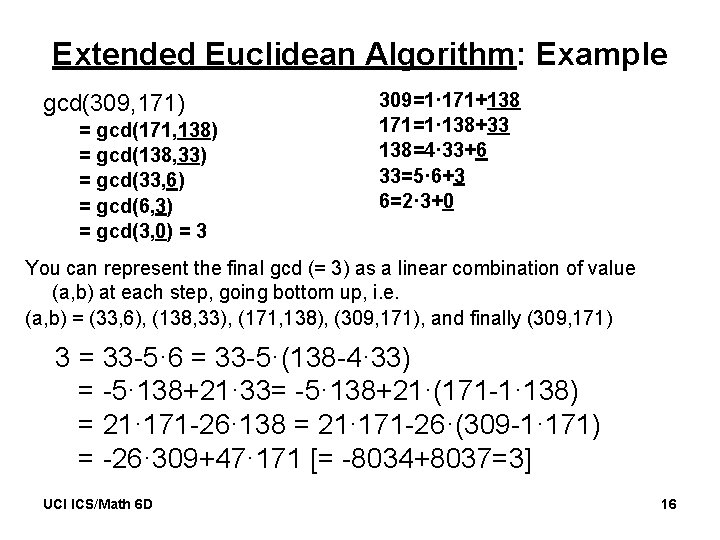

Extended Euclidean Algorithm: Example gcd(309, 171) = gcd(171, 138) = gcd(138, 33) = gcd(33, 6) = gcd(6, 3) = gcd(3, 0) = 3 309=1· 171+138 171=1· 138+33 138=4· 33+6 33=5· 6+3 6=2· 3+0 You can represent the final gcd (= 3) as a linear combination of value (a, b) at each step, going bottom up, i. e. (a, b) = (33, 6), (138, 33), (171, 138), (309, 171), and finally (309, 171) 3 = 33 -5· 6 = 33 -5·(138 -4· 33) = -5· 138+21· 33= -5· 138+21·(171 -1· 138) = 21· 171 -26· 138 = 21· 171 -26·(309 -1· 171) = -26· 309+47· 171 [= -8034+8037=3] UCI ICS/Math 6 D 16

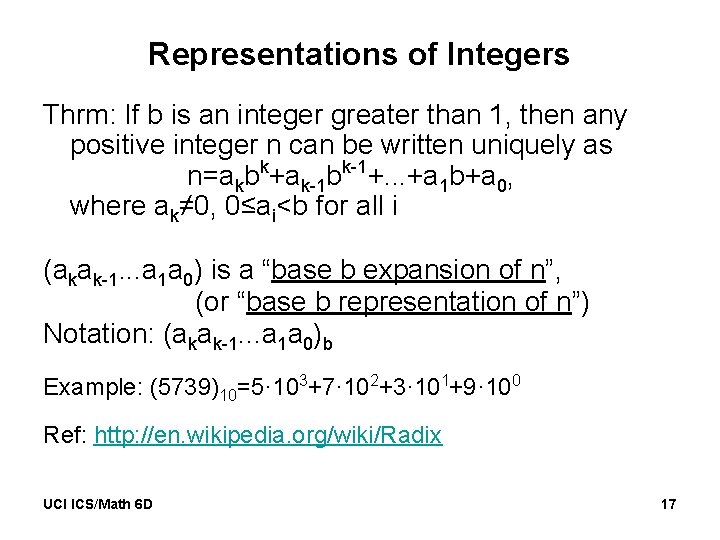

Representations of Integers Thrm: If b is an integer greater than 1, then any positive integer n can be written uniquely as n=akbk+ak-1 bk-1+. . . +a 1 b+a 0, where ak≠ 0, 0≤ai<b for all i (akak-1. . . a 1 a 0) is a “base b expansion of n”, (or “base b representation of n”) Notation: (akak-1. . . a 1 a 0)b Example: (5739)10=5· 103+7· 102+3· 101+9· 100 Ref: http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Radix UCI ICS/Math 6 D 17

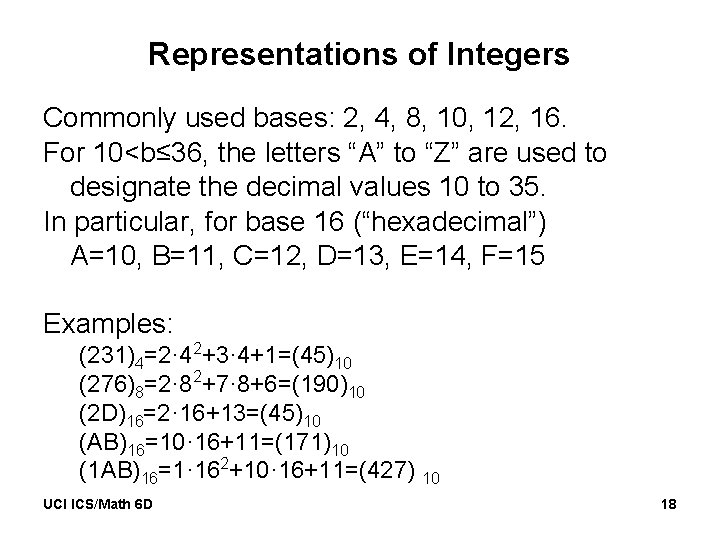

Representations of Integers Commonly used bases: 2, 4, 8, 10, 12, 16. For 10<b≤ 36, the letters “A” to “Z” are used to designate the decimal values 10 to 35. In particular, for base 16 (“hexadecimal”) A=10, B=11, C=12, D=13, E=14, F=15 Examples: (231)4=2· 42+3· 4+1=(45)10 (276)8=2· 82+7· 8+6=(190)10 (2 D)16=2· 16+13=(45)10 (AB)16=10· 16+11=(171)10 (1 AB)16=1· 162+10· 16+11=(427) 10 UCI ICS/Math 6 D 18

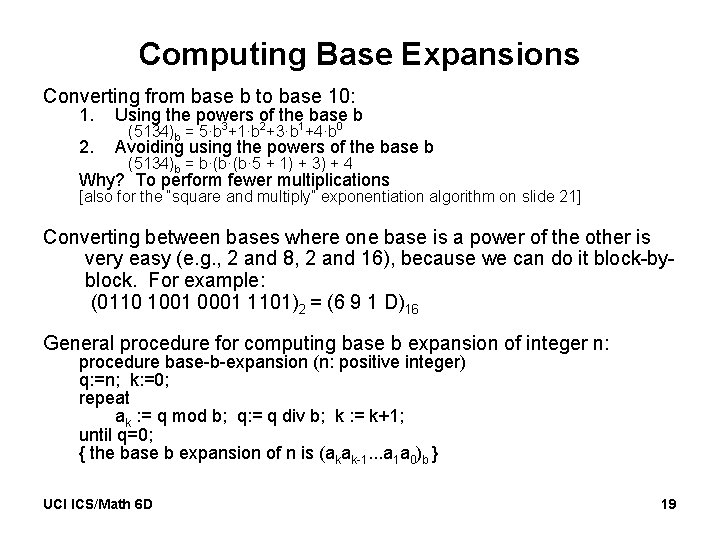

Computing Base Expansions Converting from base b to base 10: 1. Using the powers of the base b 2. Avoiding using the powers of the base b (5134)b = 5·b 3+1·b 2+3·b 1+4·b 0 (5134)b = b·(b·(b· 5 + 1) + 3) + 4 Why? To perform fewer multiplications [also for the “square and multiply” exponentiation algorithm on slide 21] Converting between bases where one base is a power of the other is very easy (e. g. , 2 and 8, 2 and 16), because we can do it block-byblock. For example: (0110 1001 0001 1101)2 = (6 9 1 D)16 General procedure for computing base b expansion of integer n: procedure base-b-expansion (n: positive integer) q: =n; k: =0; repeat ak : = q mod b; q: = q div b; k : = k+1; until q=0; { the base b expansion of n is (akak-1. . . a 1 a 0)b } UCI ICS/Math 6 D 19

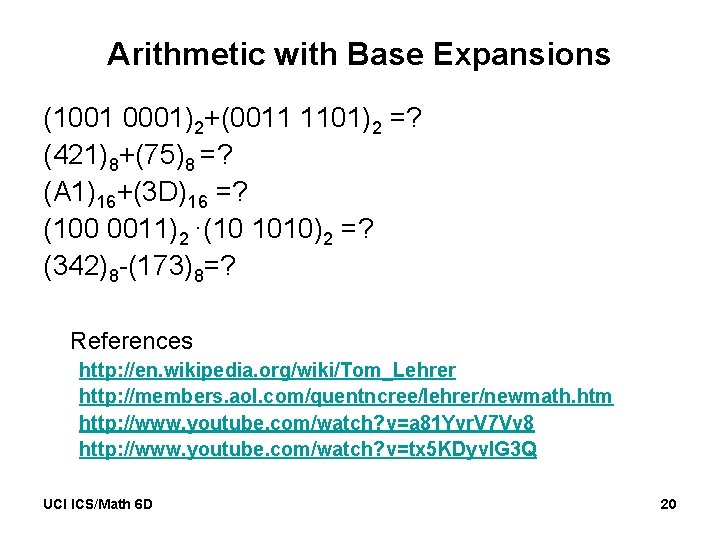

Arithmetic with Base Expansions (1001 0001)2+(0011 1101)2 =? (421)8+(75)8 =? (A 1)16+(3 D)16 =? (100 0011)2 ·(10 1010)2 =? (342)8 -(173)8=? References http: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Tom_Lehrer http: //members. aol. com/quentncree/lehrer/newmath. htm http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=a 81 Yvr. V 7 Vv 8 http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=tx 5 KDyvl. G 3 Q UCI ICS/Math 6 D 20

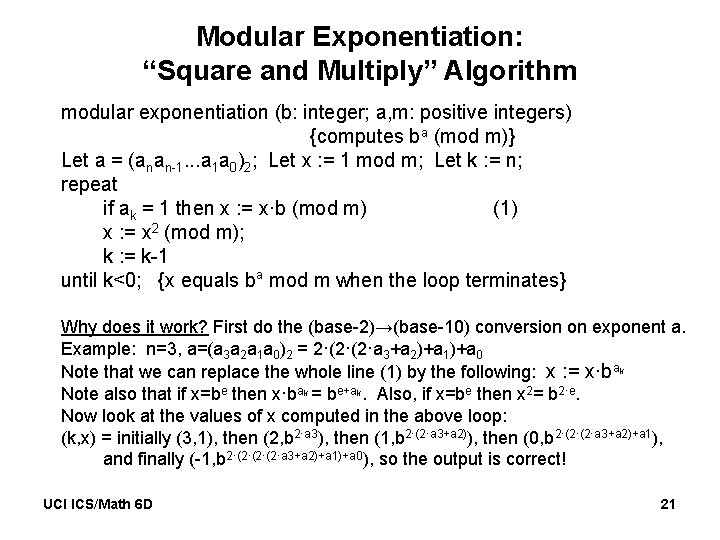

Modular Exponentiation: “Square and Multiply” Algorithm modular exponentiation (b: integer; a, m: positive integers) {computes ba (mod m)} Let a = (anan-1. . . a 1 a 0)2; Let x : = 1 mod m; Let k : = n; repeat if ak = 1 then x : = x·b (mod m) (1) x : = x 2 (mod m); k : = k-1 until k<0; {x equals ba mod m when the loop terminates} Why does it work? First do the (base-2)→(base-10) conversion on exponent a. Example: n=3, a=(a 3 a 2 a 1 a 0)2 = 2·(2·(2·a 3+a 2)+a 1)+a 0 Note that we can replace the whole line (1) by the following: x : = x·bak Note also that if x=be then x·bak = be+ak. Also, if x=be then x 2= b 2·e. Now look at the values of x computed in the above loop: (k, x) = initially (3, 1), then (2, b 2·a 3), then (1, b 2·(2·a 3+a 2)), then (0, b 2·(2·(2·a 3+a 2)+a 1), and finally (-1, b 2·(2·(2·(2·a 3+a 2)+a 1)+a 0), so the output is correct! UCI ICS/Math 6 D 21

- Slides: 21