Instrumental Conditioning Procedures Review of Instrumental Contingency Punishment

- Slides: 31

Instrumental Conditioning Procedures • Review of Instrumental Contingency – Punishment : behavior followed by an aversive • decreases the behavior – Picking up a hot object hurts • so do not touch it in the future • Sometimes called “passive” avoidance – Negative reinforcement : behavior to prevent an aversive • increases the behavior • Using a glove to pick up a hot object avoids getting hurt – so use the glove in the future • Called “active” avoidance behavior • Similarity between passive and active avoidance: – Both serve to minimize contact with the aversive stimulus

Origins of the Study of Avoidance Behavior • First experiments conducted by Bechterev (1913) • Based on Pavlov’s classical conditioning using an aversive US Participants instructed to place a finger on a metal plate A warning stimulus (CS) was then presented, followed by a brief shock (US) So this is fear conditioning The participants quickly lifted their finger off the plate after being shocked, which is escape behavior – After a few trials, they also learned to make the response during the CS so they did not get shocked, which is avoidance behavior – – • This is instrumental conditioning (negative reinforcement)

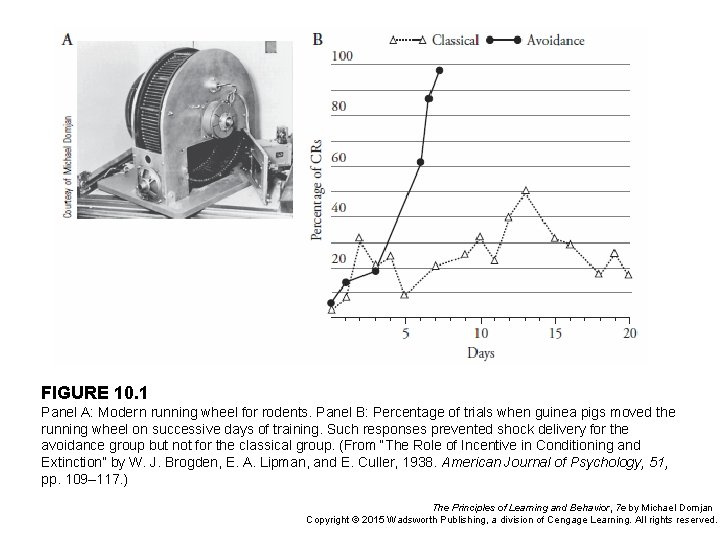

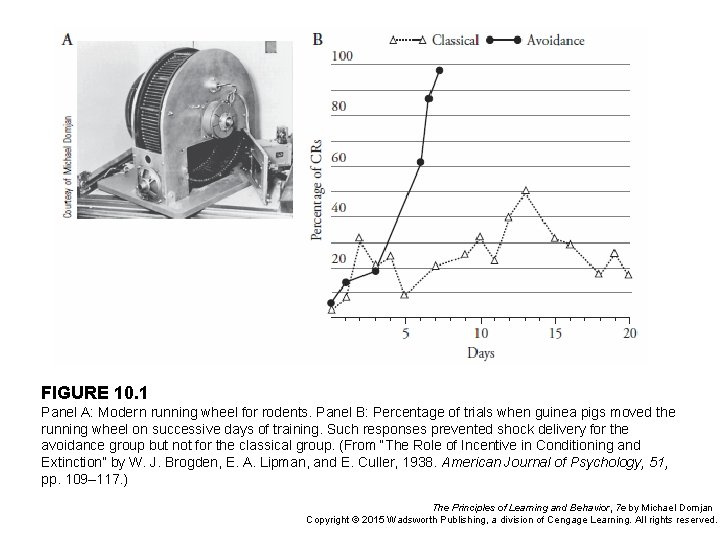

Origins of the Study of Avoidance Behavior • Brogden, Lipman, & Culler (1938) – compared standard classical conditioning procedure and instrumental avoidance – Tested 2 groups of guinea pigs in a rotating wheel – A tone served as the CS and a shock as the US • The shock stimulated the animals to run and rotate the wheel “escape” – For the classical conditioning group • the shock was presented 2 s after the onset of the tone even if they run – For the avoidance conditioning group • if they moved the wheel during the tone CS before the shock occurred, the scheduled shock was omitted – See Figure 10. 1

FIGURE 10. 1 Panel A: Moder n running wheel for rodents. Panel B: Percentage of trials when guinea pigs moved the running wheel on successive days of training. Such responses prevented shock delivery for the avoidance group but not for the classical group. (From “The Role of Incentive in Conditioning and Extinction” by W. J. Brogden, E. A. Lipman, and E. Culler, 1938. American Journal of Psychology, 51, pp. 109– 117. ) The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

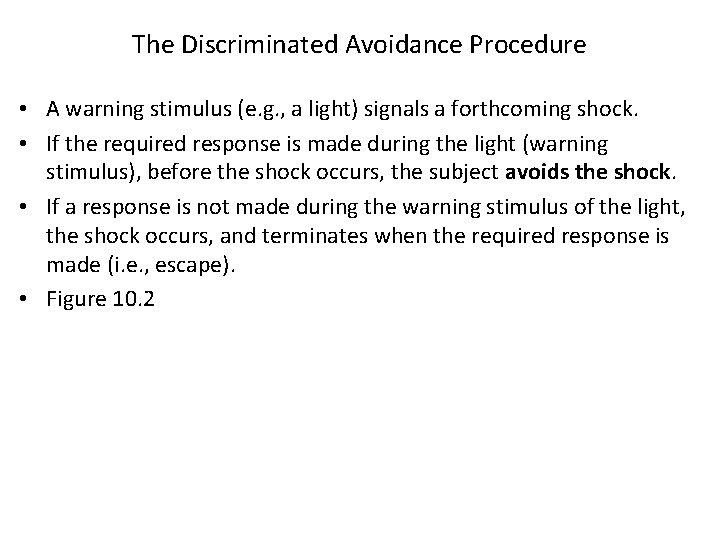

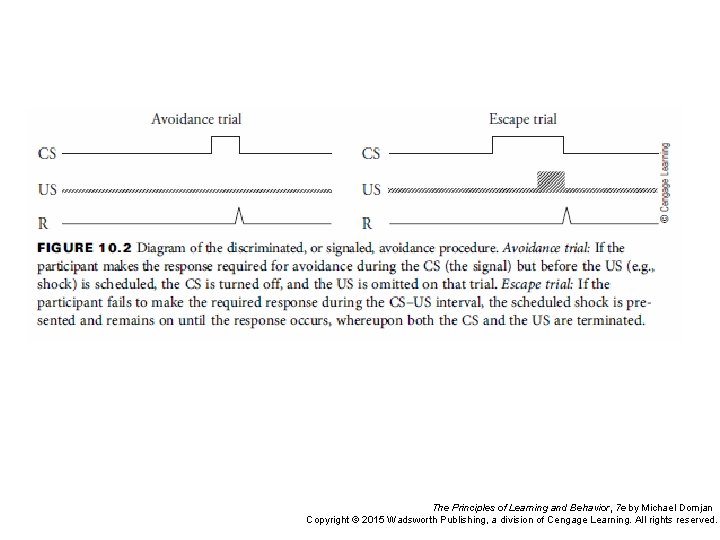

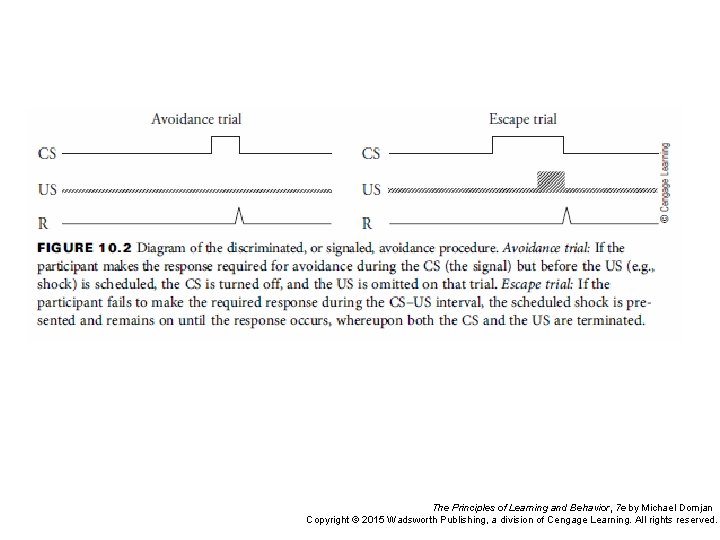

The Discriminated Avoidance Procedure • A warning stimulus (e. g. , a light) signals a forthcoming shock. • If the required response is made during the light (warning stimulus), before the shock occurs, the subject avoids the shock. • If a response is not made during the warning stimulus of the light, the shock occurs, and terminates when the required response is made (i. e. , escape). • Figure 10. 2

The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

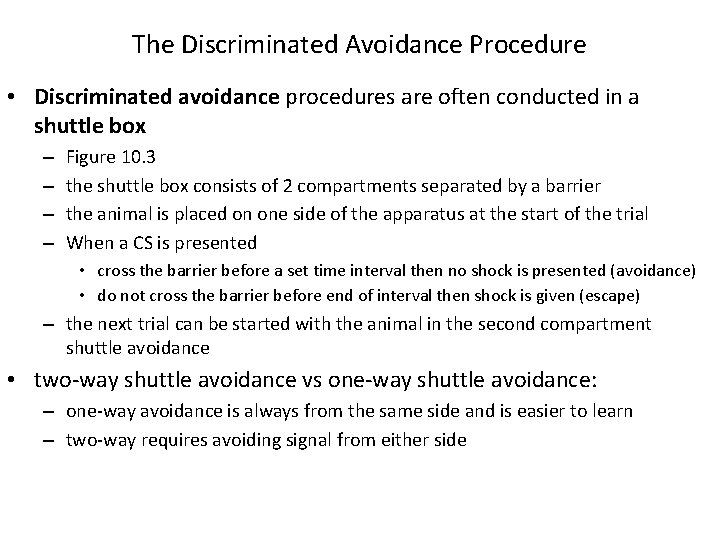

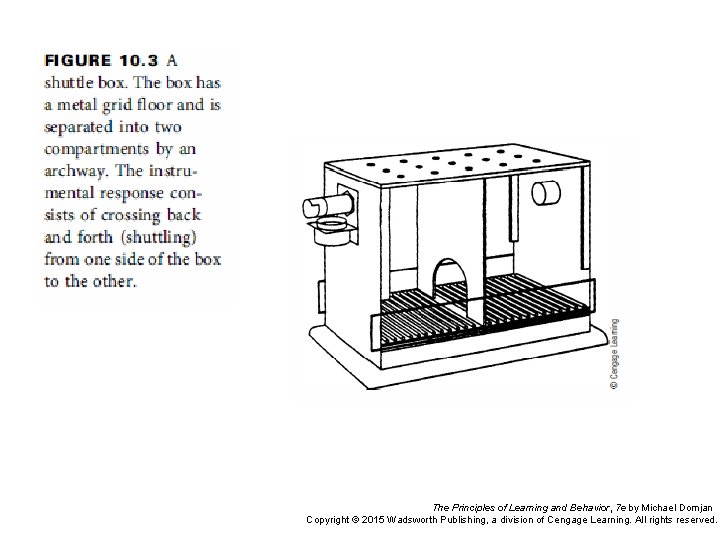

The Discriminated Avoidance Procedure • Discriminated avoidance procedures are often conducted in a shuttle box – – Figure 10. 3 the shuttle box consists of 2 compartments separated by a barrier the animal is placed on one side of the apparatus at the start of the trial When a CS is presented • cross the barrier before a set time interval then no shock is presented (avoidance) • do not cross the barrier before end of interval then shock is given (escape) – the next trial can be started with the animal in the second compartment shuttle avoidance • two-way shuttle avoidance vs one-way shuttle avoidance: – one-way avoidance is always from the same side and is easier to learn – two-way requires avoiding signal from either side

The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

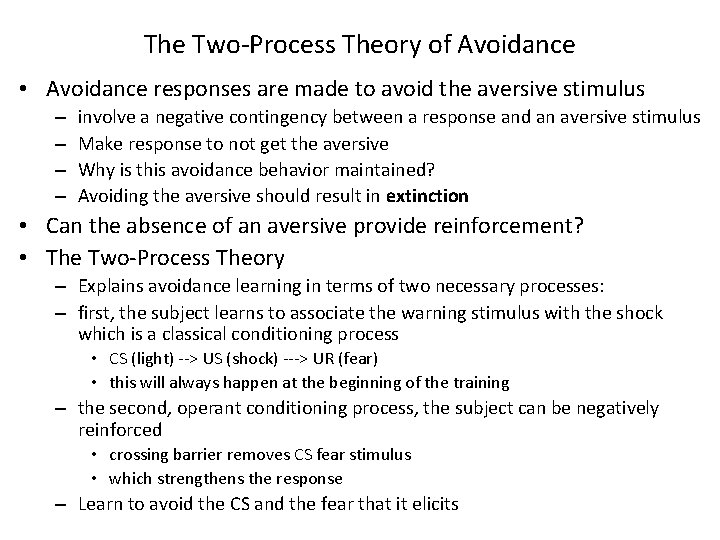

The Two-Process Theory of Avoidance • Avoidance responses are made to avoid the aversive stimulus – – involve a negative contingency between a response and an aversive stimulus Make response to not get the aversive Why is this avoidance behavior maintained? Avoiding the aversive should result in extinction • Can the absence of an aversive provide reinforcement? • The Two-Process Theory – Explains avoidance learning in terms of two necessary processes: – first, the subject learns to associate the warning stimulus with the shock which is a classical conditioning process • CS (light) --> US (shock) ---> UR (fear) • this will always happen at the beginning of the training – the second, operant conditioning process, the subject can be negatively reinforced • crossing barrier removes CS fear stimulus • which strengthens the response – Learn to avoid the CS and the fear that it elicits

Experimental Analysis of Avoidance Behavior • Experimental procedures used to test the Two-Process Theory • Escape From Fear (EFF) Experiments • In the typical avoidance procedure, classical conditioning of fear and instrumental reinforcement through fear reduction occur intermixed in a series of trial • If Two-Process theory is right, then separating the two processes should still lead to successful learning. • Two phases : – First, classical conditioning to acquire fear of CS – Second, escape training with CS as Aversive stimulus • (US no longer presented) – will the subject learn a response to escape from just the CS

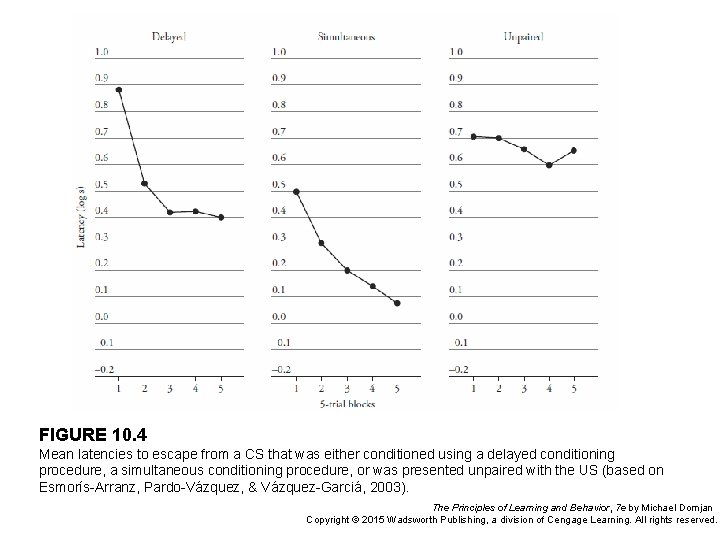

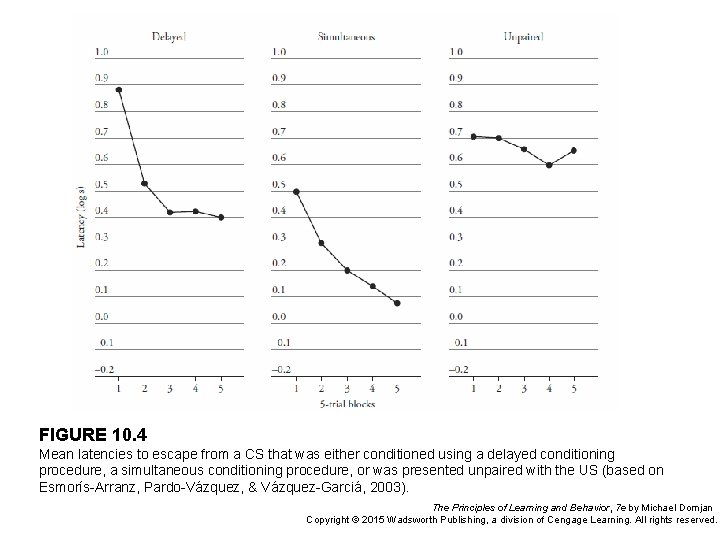

Experimental Analysis of Avoidance Behavior • Esmoris-Arranz (2003) EFF procedure – Fear Conditioning: • In one side of the box with no escape possible • 15 sec CS audiovisual + 15 sec US shock – simultaneous CS/US – delayed CS then US – Control group with unpaired CS and US – Escape Testing: placed in shuttle box with access to other side • Turn on the CS • Measure latency to move to the other side • Evidence of learning in both the delayed and simultaneous groups but not in the unpaired group • Figure 10. 4

FIGURE 10. 4 Mean latencies to escape from a CS that was either conditioned using a delayed conditioning procedure, a simultaneous conditioning procedure, or was presented unpaired with the US (based on Esmorís-Arranz, Pardo-Vázquez, & Vázquez-Garciá, 2003). The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Independent Measurement of Fear During Acquisition of Avoidance Behavior • If fear motivates and reinforces avoidance responding, then the conditioning of fear and the conditioning of instrumental avoidance behavior should be highly correlated • However, the level of fear is not always positively correlated with avoidance • Animals often become less fearful as they become more proficient in performing the avoidance response • A warning signal (CS) in an avoidance procedure comes to elicit fear – presentation of that stimulus in a conditioned suppression procedure should result in suppression of behavior – Gradual reduction in fear of the warning signal even though avoidance behavior continues

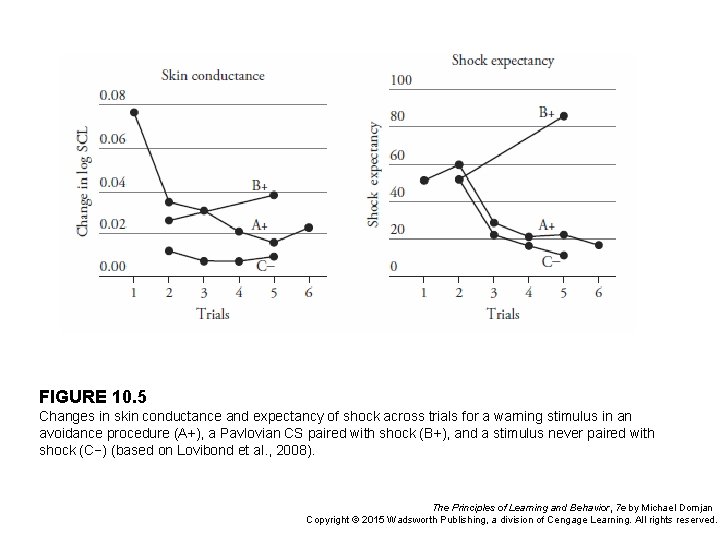

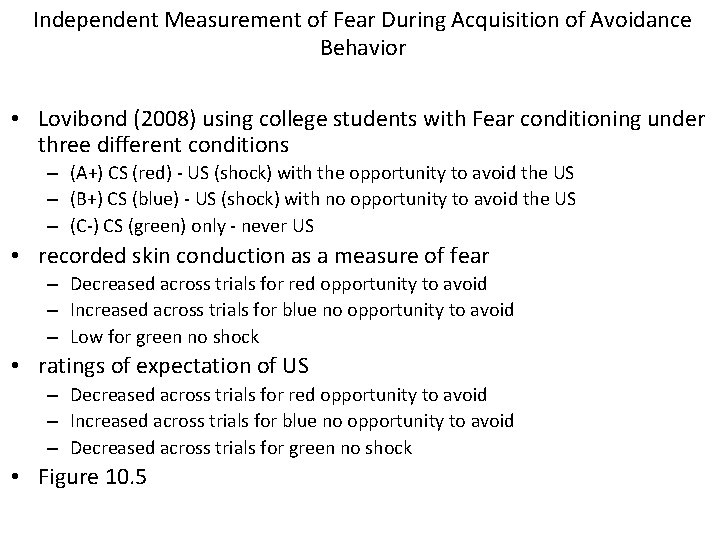

Independent Measurement of Fear During Acquisition of Avoidance Behavior • Lovibond (2008) using college students with Fear conditioning under three different conditions – (A+) CS (red) - US (shock) with the opportunity to avoid the US – (B+) CS (blue) - US (shock) with no opportunity to avoid the US – (C-) CS (green) only - never US • recorded skin conduction as a measure of fear – Decreased across trials for red opportunity to avoid – Increased across trials for blue no opportunity to avoid – Low for green no shock • ratings of expectation of US – Decreased across trials for red opportunity to avoid – Increased across trials for blue no opportunity to avoid – Decreased across trials for green no shock • Figure 10. 5

FIGURE 10. 5 Changes in skin conductance and expectancy of shock across trials for a warning stimulus in an avoidance procedure (A+), a Pavlovian CS paired with shock (B+), and a stimulus never paired with shock (C−) (based on Lovibond et al. , 2008). The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Extinction of Avoidance Behavior Through Response-Blocking and CS-Alone Exposure • Avoidance behavior can be very persistent – It is difficult to extinguish avoidance behavior • Avoidance behavior removes aversive situations – It is successfully preventing an aversive outcome – Situations that produce fear and expectancy of threat motivate avoidance • A good thing if it is a truck coming at you • However, avoiding school is maladaptive

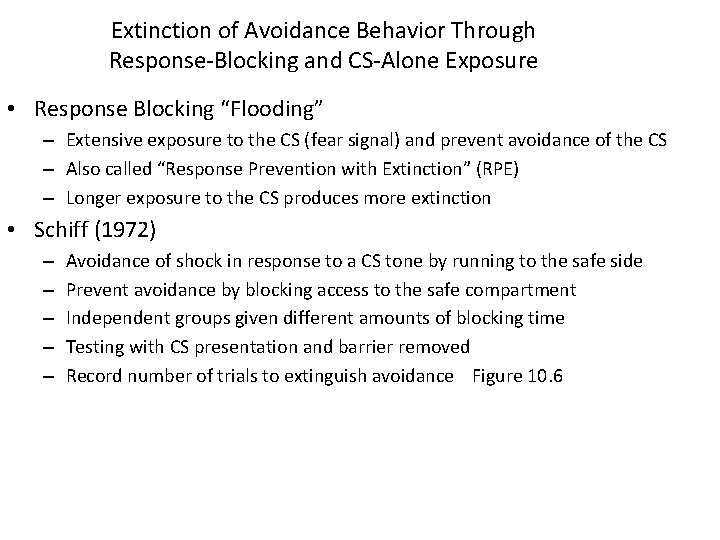

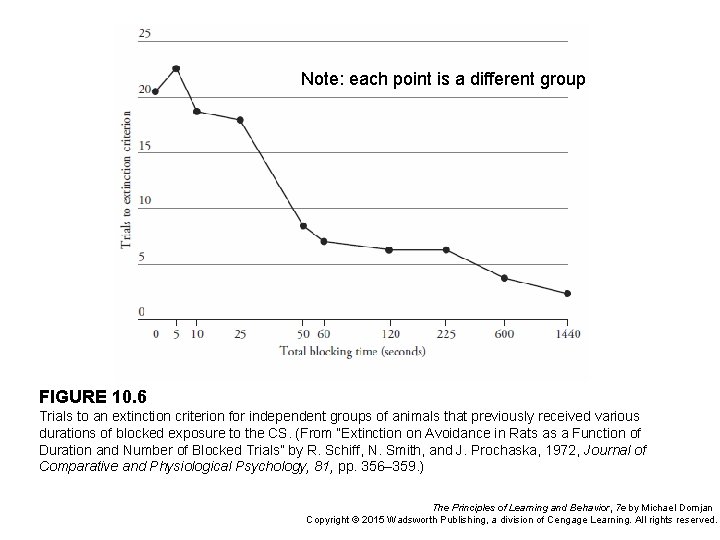

Extinction of Avoidance Behavior Through Response-Blocking and CS-Alone Exposure • Response Blocking “Flooding” – Extensive exposure to the CS (fear signal) and prevent avoidance of the CS – Also called “Response Prevention with Extinction” (RPE) – Longer exposure to the CS produces more extinction • Schiff (1972) – – – Avoidance of shock in response to a CS tone by running to the safe side Prevent avoidance by blocking access to the safe compartment Independent groups given different amounts of blocking time Testing with CS presentation and barrier removed Record number of trials to extinguish avoidance Figure 10. 6

Note: each point is a different group FIGURE 10. 6 Trials to an extinction criterion for independent groups of animals that previously received various durations of blocked exposure to the CS. (From “Extinction on Avoidance in Rats as a Function of Duration and Number of Blocked Trials” by R. Schiff, N. Smith, and J. Prochaska, 1972, Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 81, pp. 356– 359. ) The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Flooding with Response Blocking • Bravo-Rivera (2015) – behavioral conflict study with hungry rats pressing a lever food with occasional foot shock avoid shock by jumping on a platform but can not get any food while on the platform RPE (flooding): Removal of the platform (no shocks delivered) – initially increased fear-related freezing that subsequently extinguished • returning the platform to the cage (but no shock) – return of shock-avoidance responses, despite complete fear extinction • • • Avoidance behavior is persistent and difficult to extinguish – An important part of exposure-based treatments (flooding) • identify and neutralize avoidance behaviors • If children are skipping school what are they doing instead? • To improve extinction of the fear or anxiety

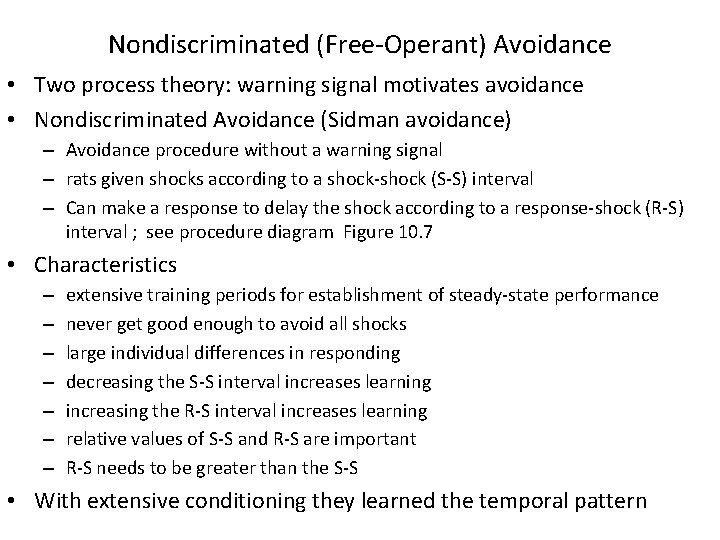

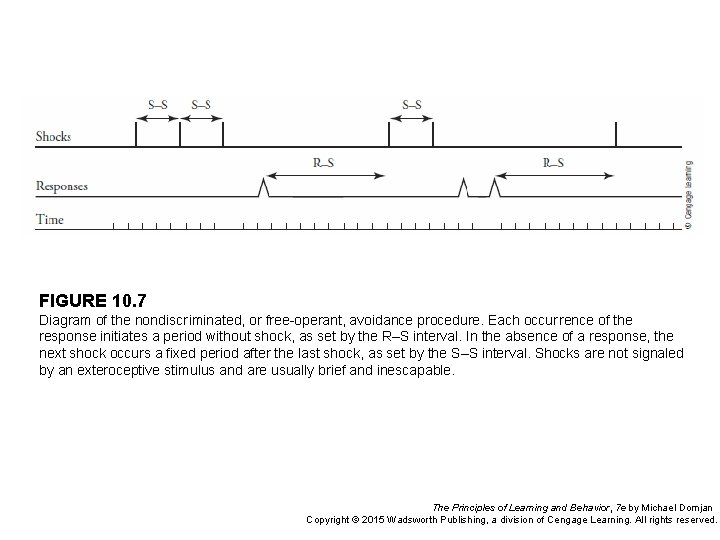

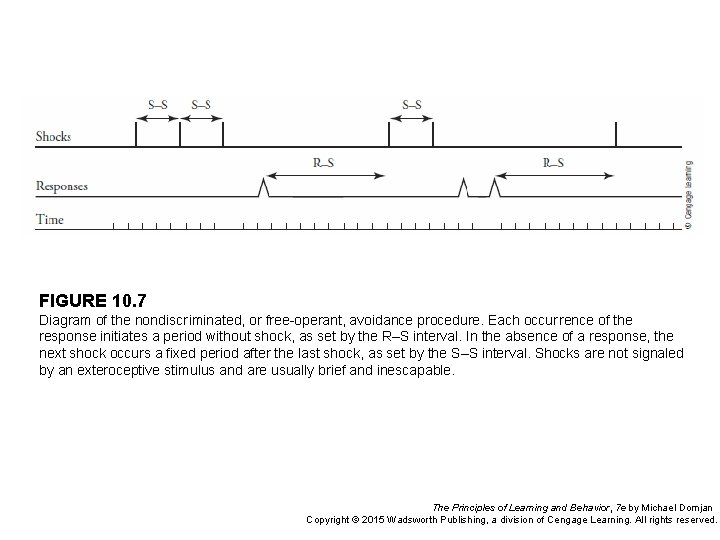

Nondiscriminated (Free-Operant) Avoidance • Two process theory: warning signal motivates avoidance • Nondiscriminated Avoidance (Sidman avoidance) – Avoidance procedure without a warning signal – rats given shocks according to a shock-shock (S-S) interval – Can make a response to delay the shock according to a response-shock (R-S) interval ; see procedure diagram Figure 10. 7 • Characteristics – – – – extensive training periods for establishment of steady-state performance never get good enough to avoid all shocks large individual differences in responding decreasing the S-S interval increases learning increasing the R-S interval increases learning relative values of S-S and R-S are important R-S needs to be greater than the S-S • With extensive conditioning they learned the temporal pattern

FIGURE 10. 7 Diagram of the nondiscr iminated, or free-operant, avoidance procedure. Each occur rence of the response initiates a period without shock, as set by the R–S interval. In the absence of a response, the next shock occurs a fixed period after the last shock, as set by the S–S interval. Shocks are not signaled by an exteroceptive stimulus and are usually brief and inescapable. The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

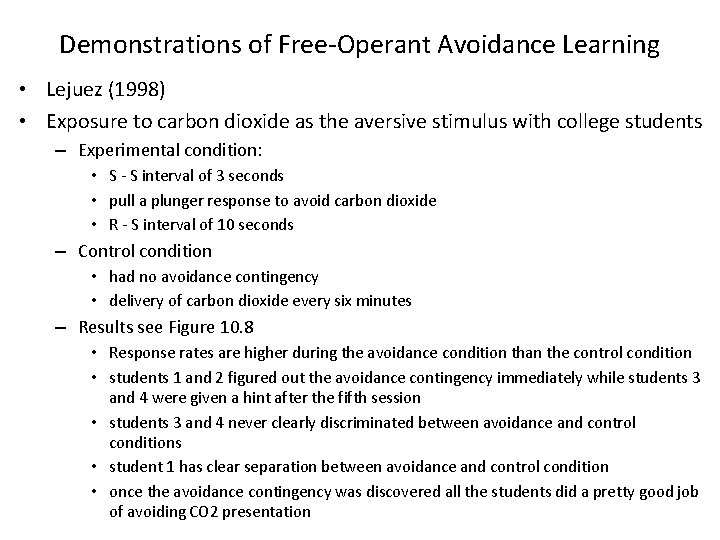

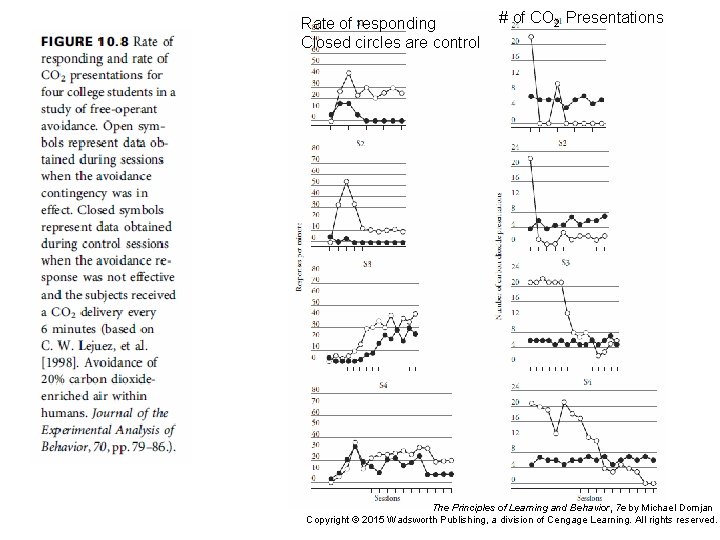

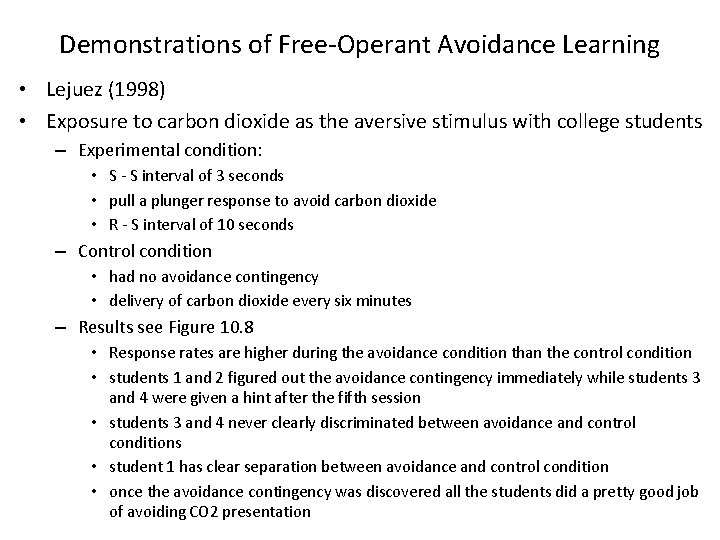

Demonstrations of Free-Operant Avoidance Learning • Lejuez (1998) • Exposure to carbon dioxide as the aversive stimulus with college students – Experimental condition: • S - S interval of 3 seconds • pull a plunger response to avoid carbon dioxide • R - S interval of 10 seconds – Control condition • had no avoidance contingency • delivery of carbon dioxide every six minutes – Results see Figure 10. 8 • Response rates are higher during the avoidance condition than the control condition • students 1 and 2 figured out the avoidance contingency immediately while students 3 and 4 were given a hint after the fifth session • students 3 and 4 never clearly discriminated between avoidance and control conditions • student 1 has clear separation between avoidance and control condition • once the avoidance contingency was discovered all the students did a pretty good job of avoiding CO 2 presentation

Rate of responding Closed circles are control # of CO 2 Presentations The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Free-Operant Avoidance and the Two-Process Theory • Can Free-Operant Avoidance be explained by two-process theory? – No explicit, external CS to elicit fear – there is an internal cue – Passage of time since the last shock elicits fear • Termination of time signals reinforce responding through fear reduction • Concentration at end of R-S interval because temporal cues elicit greatest fear at this point

Alternative Theoretical Accounts of Avoidance Behavior • 1. Positive Reinforcement Through Conditioned Inhibition of Fear or Conditioned Safety Signals • Safety signals: ‘Feedback’ cues from avoidance responding are spatial, tactile and proprioceptive cues associated with avoidance – Cues during avoidance behavior • Safety signal hypothesis – Feedback cues can produce conditioned inhibitory properties – Feedback cues could be a source of positive reinforcement. • Context of the safe side of a shuttle box • Distinctive stimulus (light) presented after avoidance response will facilitates avoidance • Can explain free-operant avoidance – If sensations from movements during R-S (safety period) develop conditioned inhibitory properties.

Alternative Theoretical Accounts of Avoidance Behavior • 2. Reinforcement of avoidance Through Reduction of Shock Frequency • reduction in shock frequency with avoidance responses • Reduction in shock frequency could reinforces avoidance behavior • Some experiments have shown that avoidance behavior will still occur even if the shock frequency is not altered – this can be done by delaying the shock delivery

Alternative Theoretical Accounts of Avoidance Behavior • 3. Avoidance and Species-Specific Defense Reactions (SSDRs) – In natural environment, avoidance learning needs to occur quickly – Various defensive behaviors (SSDRs) can occur in response to aversive stimuli (e. g. , running, freezing, defensive fighting, approaching walls, etc. ) – Which defensive behavior depends on environment – If ‘chosen’ SSDR works, keep using it; if it does not, punishment occurs, and another SSDR employed – Attributes instrumental avoidance to punishment rather than reinforcement – Consistent with SSDR predictions, certain behaviors more conducive to learning in avoidance experiments (i. e. , running more appropriate then standing on hind legs) – Some issues with SSDR theory explaining experimental findings – Punishment sometimes facilitates (rather than suppresses) ineffective defensive responses

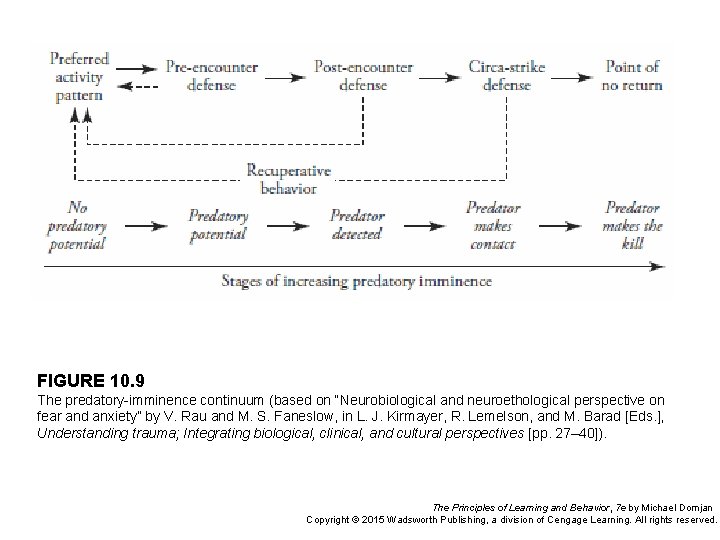

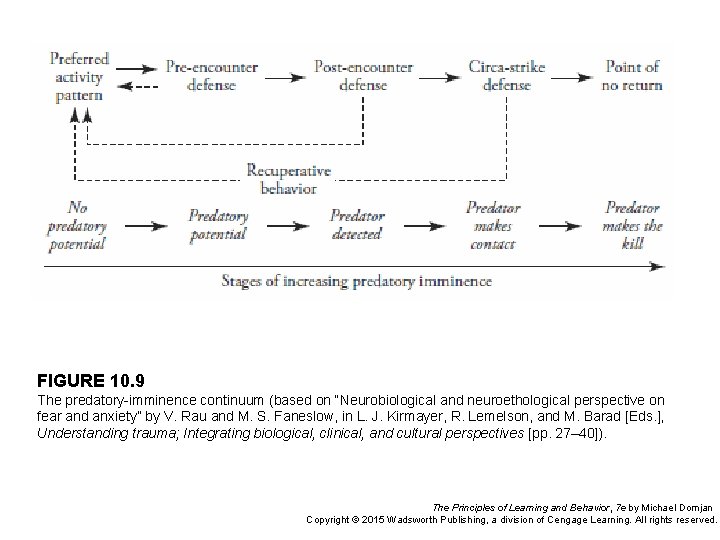

Predatory imminence and Defensive and Recuperative Behaviors • Predatory imminence continuum: – response based on predator threat potential see Figure 10. 9 • • rats are reasonably safe in their borrow but have to occasionally go out to find food when predators are in the area level of danger increases when predators are close enough to strike “circa strike” danger is at its peak • Animals make behavioral adjustments to the level of danger – for example when predator is detected rats go out less often but eat larger meals when they go out – Animals can also adjust their defensive behaviors within the imminence is low rats may freeze holding still so that there are less likely to be detected – when the predator gets close and actually makes contact the rat can leap into the air as an “circa strike response” to escape • Defensive behaviors are guided by unconditioned responses – The behavior will be adjusted by encounters with predators – Predator cue to predator encounter temporal pattern determines type of behavioral adjustment

FIGURE 10. 9 The predatory-imminence continuum (based on “Neurobiological and neuroethological perspective on fear and anxiety” by V. Rau and M. S. Faneslow, in L. J. Kirmayer, R. Lemelson, and M. Barad [Eds. ], Understanding trauma; Integrating biological, clinical, and cultural perspectives [pp. 27– 40]). The Principles of Learning and Behavior, 7 e by Michael Domjan Copyright © 2015 Wadsworth Publishing, a division of Cengage Learning. All rights reserved.

Expectancy Theory of Avoidance • Experiments with non-human animals such as rats – Unconscious associative conditioning processes – Might have some elements of expectancy • Experiments with humans – form associations that do not require conscious awareness – can also have conscious expectancy of the contingency • Threat appraisal to determine possibility of aversive events • which will influence conditioning and extinction rates • Can explain persistent avoidance behavior – Expectancy of no aversive if response is preformed » “pushing the button when I see a blue square will prevent the shock to my finger” – Is this the primary cause of persistent avoidance in humans?

The Avoidance Puzzle: Concluding Comments • Two-Process theory • How can not getting something act as a motivator? – conditioned inhibition reinforcement – shock frequency-reduction reinforcement – SSDR and Predatory imminence